Background: Carbonic anhydrase II (CAII) augments activity of monocarboxylate transporters (MCTs) by noncatalytic interaction.

Results: CAII binds to an acidic cluster with an appropriate context in the MCT C terminus.

Conclusion: Isoform-specific interaction between MCTs and CAII requires a specific binding moiety.

Significance: CAII-mediated increase in lactate transport depends on the presence of a specific binding moiety in MCT.

Keywords: Ion-sensitive Electrode, Lactic Acid, pH Regulation, Protein Complex, Protein Expression, Proton Transport, Xenopus

Abstract

Proton-coupled monocarboxylate transporters (MCTs) mediate the exchange of high energy metabolites like lactate between different cells and tissues. We have reported previously that carbonic anhydrase II augments transport activity of MCT1 and MCT4 by a noncatalytic mechanism, while leaving transport activity of MCT2 unaltered. In the present study, we combined electrophysiological measurements in Xenopus oocytes and pulldown experiments to analyze the direct interaction between carbonic anhydrase II (CAII) and MCT1, MCT2, and MCT4, respectively. Transport activity of MCT2-WT, which lacks a putative CAII-binding site, is not augmented by CAII. However, introduction of a CAII-binding site into the C terminus of MCT2 resulted in CAII-mediated facilitation of MCT2 transport activity. Interestingly, introduction of three glutamic acid residues alone was not sufficient to establish a direct interaction between MCT2 and CAII, but the cluster had to be arranged in a fashion that allowed access to the binding moiety in CAII. We further demonstrate that functional interaction between MCT4 and CAII requires direct binding of the enzyme to the acidic cluster 431EEE in the C terminus of MCT4 in a similar fashion as previously shown for binding of CAII to the cluster 489EEE in the C terminus of MCT1. In CAII, binding to MCT1 and MCT4 is mediated by a histidine residue at position 64. Taken together, our results suggest that facilitation of MCT transport activity by CAII requires direct binding between histidine 64 in CAII and a cluster of glutamic acid residues in the C terminus of the transporter that has to be positioned in surroundings that allow access to CAII.

Introduction

The SLC16 gene family of monocarboxylate transporters (MCTs)2 comprises 14 isoforms, the first four of which carry high energy metabolites, such as lactate, pyruvate, and ketone bodies together with H+ in a 1:1 stoichiometry (1–5). MCT1 is found in nearly all tissues, where it operates either as a lactate importer or exporter (3–5). MCT1 has an intermediate Km value of 3–5 mm for l-lactate (1, 2). MCT2, which is primarily found in liver, kidney, testis, and brain (6–8), has the highest affinity for l-lactate among all MCTs with a Km value of ∼0.7 mm (9). In liver and kidney, MCT2 facilitates the uptake of lactate, which is used for glyconeogenesis in these tissues (3). In the brain, MCT2 is expressed in neurons, where it facilitates the import of lactate, which is exported from astrocytes and vascular endothelial cells via MCT1 and MCT4 (10–13). Expression of MCT3 is restricted to retinal pigment epithelium and choroid plexus epithelia, where it primarily serves as a lactate exporter (14–16). MCT3 transports l-lactate with a Km of ∼6 mm (17). MCT4 is a low affinity, high capacity carrier with a Km value of 20–35 mm for l-lactate (18). It primarily acts as a lactate exporter in glycolytic cells and tissues like astrocytes, skeletal muscle, and (hypoxic) tumor cells (3, 5, 19, 20). All MCTs have a 12-transmembrane helix structure, with both the C and N termini located intracellularly (3, 5). Trafficking, but also regulation of transport activity of MCT1–4, is mediated by ancillary proteins. MCT1 and MCT4 are associated with basigin (CD147), whereas surface expression and transport activity of MCT2 is facilitated by embigin (GP70) (21, 22).

Mammalian carbonic anhydrases (CA), included in the α-class of CAs, of which 16 isoforms are identified, catalyze the reversible hydration of CO2 to HCO3− and H+ (23, 24). Cytosolic CAII has been found to bind to and facilitate transport function of many acid/base transporting membrane proteins, including the Cl−/HCO3− exchangers AE1 and AE2 (25–29), the Na+/HCO3− cotransporters NBCe1 and NBCn1 (30–36) and the Na+/H+ exchanger NHE1 (37, 38), a phenomenon coined “transport metabolon.” In all cases, CAII was found to bind to an acidic cluster within the C-terminal tail of the transport protein. In AE1, 886LDADD was identified as CAII binding site (27, 28), whereas binding of CAII to AE2 requires the corresponding cluster 1216LDANE (27). In NBCe1, the acidic clusters 958LDDV and 986DNDD are suggested to bind CAII (33, 34), and in NBCn1, binding to CAII is mediated by Asp1135 and Asp1136 (35). Binding of CAII to NHE1 involves the penultimate group of 13 amino acids of the transporter C terminus (790RIQRCLSDPGPHP), with the amino acids Ser796 and Asp797 playing an essential role in the binding (37, 38). For a more comprehensive review on bicarbonate transport metabolons see Refs. 39–41.

Using heterologous protein expression in Xenopus oocytes, we have recently reported that CAII enhances transport activity of MCT1 and MCT4, while leaving transport activity of MCT2 unaffected (42–46). In contrast to the transport metabolons described so far, this interaction is independent of CAII catalytic activity but is mediated by an intramolecular H+ shuttle within the enzyme (47, 48). This led to the conclusion that CAII, directly bound to the transporter, can act as a H+-collecting/distributing antenna, which shuttles protons between transporter and surrounding protonatable residues to support proton/lactate cotransport (48). By introduction of single-site mutations in the C terminus of MCT1 and subsequent expression of these mutants in CAII-injected Xenopus oocytes, we could identify the two glutamic acidic residues Glu489 and Glu491, flanking the cluster 489EEE within the MCT1 C terminus, to be crucial for the functional interaction with CAII (49). In the same study, a direct binding between CAII and a GST fusion protein of the MCT1 C terminus could be shown by coimmunoprecipitation when the acidic cluster 489EEE was intact, whereas mutation of Glu489 and/or Glu491 suppressed binding between MCT1-CT and CAII. This suggests that cytosolic CAII can bind to the C terminus of MCT1, which presumably positions the enzyme close enough to the pore of the transporter for efficient H+ shuttling.

In the present study, we could demonstrate that introduction of a CAII binding site into the C terminus of MCT2 induced CAII-mediated facilitation of MCT2 transport activity. However, binding and functional interaction between MCT2 and CAII could only be achieved when the two glutamic acid residues mediating binding to CAII were located in a moiety that allowed their access to the enzyme. This demonstrates that the sole presence of an acidic amino acid cluster within the C terminus of a transport protein is not sufficient to mediate binding of CAII to this transporter but that the amino acid environment needs to allow free access of the binding site to CAII. We further show that binding between CAII and MCT4 is mediated by the amino acids His64 in CAII and Glu431/Glu433 in the C terminus of MCT4, whereas binding between CAII and MCT1 involves CAII-His64 and MCT1-Glu489/Glu491.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Site-directed Mutation of MCT2 and MCT4

Site-directed mutation of MCT2 and MCT4 was carried out by PCR using a mix of Taq and Pfu polymerases (Fermentas high fidelity PCR enzyme mix; Thermo Fisher) and modified primers, which contained the desired mutation. Primers used for creation of the different mutants are shown in Table 1. Rat MCT2 and MCT4, cloned in the oocyte expression vector pGEM-He-Juel (9, 18), were used as template. PCR was cleaned up using the Gene Jet plasmid miniprep kit (Thermo Fisher), and the template was digested with DpnI (Fermentas FastDigest DpnI; Thermo Fisher) before transformation into Escherichia coli DH5α cells.

TABLE 1.

Primers used for generation of MCT2 and MCT4 mutants

Shown are the sense primers for single-site mutation of MCT2 and MCT4. Nucleotides that differ from the wild type sequence are labeled in bold. The antisense primers had the inverse complement sequence of the sense primers.

| Mutant | Primer sequence (5′ →3′) |

|---|---|

| MCT2-K485E/S487E | CCTCCCTCAGACAGGGACGAAGAAGAGAGTATTTAACAAGTCTC |

| MCT2-R483P/D484A/K485E/S487E/I489P | CCTCCCTCAGACCCGGCCGAAGAAGAGAGTCCTTAACAAGTCTC |

| MCT4-S430X | GAGGAGGTGGCCTGAGAGGAGGAGAAG |

| MCT4-S446X | GTGAGGGTGGACTAGAGGGAGGTGGAG |

| MCT4-E431Q | GAGGTGGCCTCACAGGAGGAGAAGTC |

| MCT4-E432Q | GGCCTCAGAGCAGGAGAAGCTCCAC |

| MCT4-E433Q | GCCTCAGAGGAGCAGAAGCTCCACAAG |

| MCT4-E431Q/E432Q | GAGGTGGCCTCACAGCAGGAGAAGCTC |

| MCT4-E431Q/E433Q | GTGGCCTCACAGGAGCAGAAGCTCCAC |

| MCT4-E432Q/E433Q | GCCTCAGAGCAGCAGAAGCTCCACAAG |

| MCT4-E431Q/E432Q/E433Q | GTGGCCTCACAGCAGCAGAAGCTCCAC |

Pulldown of CAII with GST Fusion Proteins

C termini of rat MCT1-WT, rat MCT2-WT, rat MCT4-WT, and mutants of the C termini were cloned into the expression vector pGEX-2T (GE Healthcare Europe GmbH) and transformed into E. coli BL21 cells. Protein expression was induced by addition of 0.8 mm isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside. 3 h after induction, the cells were harvested and resuspended in PBS and lysed with lysis buffer (PBS, 2 mm MgCl2, 1% Triton X-100) in the presence of protease inhibitors (protease inhibitor mixture tablets; Roche). Bacterial lysates were centrifuged for 15 min at 4 °C at 12,000 × g, and the supernatant containing the GST fusion protein (bait protein) was collected for further use. CAII-WT and CAII-H64A, respectively, were expressed in Xenopus oocytes, as described in the next section. For each experiment, 25 oocytes were lysed in lysis buffer in the presence of protease inhibitors (Roche). Oocyte lysates were centrifuged for 15 min at 4 °C at 12,000 × g, and the supernatant (prey protein) was collected for further use.

The pulldown experiment was carried out using the Pierce GST protein interaction pulldown kit (Thermo Fisher). Briefly, for immobilization of GST fusion protein, 400 μg of bacterial lysate was added to a column containing 50 μl of 50% slurry of glutathione agarose and incubated for 2 h at 4 °C with end over end mixing. After incubation, the excess bait protein was removed by centrifugation (4 °C, 700 × g), and the beads were washed five times with wash buffer (1 PBS: 1 lysis buffer). 400 μl of oocyte lysate containing CAII-WT or CAII-H64A was added to the column and incubated for 2 h at 4 °C with end over end mixing. After incubation, the excess prey protein was removed by centrifugation (4 °C, 700 × g), and the beads were washed five times with wash buffer. Protein was eluted from the beads with 250 μl of elution buffer (10 mm glutathione in PBS, pH 8.0).

To determine the relative amount of GST and CAII, an equal volume of the samples was analyzed by Western blotting. GST was detected using a primary anti-GST antibody (dilution 1:400, anti-GST tag mouse monoclonal IgG, no. 05-782; Millipore) and a goat anti-mouse IgG horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (dilution 1:12000; Santa Cruz). CAII was detected using a primary anti-CAII antibody (human erythrocytes) (dilution 1:400, rabbit anti-carbonic anhydrase II polyclonal antibody, AB1828; Millipore) and a goat anti-rabbit IgG horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (dilution 1:12000; Santa Cruz). Membranes were analyzed after incubation with Luminata classic Western HRP substrate (Millipore) with an Odyssey Fc dual mode imaging system (Li-Cor Biosciences). Quantification of the band intensity was carried out with the software ImageJ. To overcome variations in the signal intensity between different blots, the signal intensity of each band for CAII was normalized to the signal intensity of the band from the pulldown of CAII with the GST fusion protein of the full-length C terminus. To account for variations in the amount of GST fusion protein, each normalized signal for CAII was divided by the corresponding, normalized signal for GST.

Heterologous Protein Expression in Xenopus Oocytes

Plasmid DNA of rat MCT1-WT, rat MCT2-WT, rat MCT4-WT, rat GP70, human CAII-WT, and mutants of the proteins, respectively, cloned into the oocyte expression vector pGEM-He-Juel, which contains the 5′ and the 3′ untranscribed regions of the Xenopus β-globin flanking the multiple cloning site, was linearized with SalI (Fermentas FastDigest SalI; Thermo Fisher) and transcribed in vitro with T7 RNA polymerase (Ambion mMessage mMachine; Life Technologies) as described earlier (50). Xenopus laevis females were purchased from Xenopus Express (Vernassal, France). Segments of ovarian lobules were surgically removed under sterile conditions from frogs anesthetized with 1 g/liter of 3-amino-benzoic acid ethylester (MS-222; Sigma-Aldrich) and rendered hypothermic. The procedure was approved by the Landesuntersuchungsamt Rheinland-Pfalz, Koblenz (23 177-07/A07-2-003 §6). Oocytes were singularized by collagenase (collagenase A; Roche) treatment and stored overnight in oocyte saline (82.5 mm NaCl, 2.5 mm KCl, 1 mm CaCl2, 1 mm MgCl2, 1 mm Na2HPO4, 5 mm HEPES), supplemented with gentamycin at 18 °C to recover. To investigate the influence of CAII on transport activity of MCT2 and MCT4, oocytes of the stages V and VI were injected with 5 ng of cRNA coding for MCT2-WT (+10 ng of GP70), MCT4-WT, or a mutant of the proteins, 3–6 days before the experiment, using a microinjection system (WPI Nanoliter 2000; World Precision Instruments Germany). Bovine CAII protein (C3934; Sigma-Aldrich) was injected in a concentration of 50 ng/oocyte 1 day before measurement. To investigate the influence of CAII mutants on MCT1 transport activity, oocytes were coinjected with 5 ng of cRNA coding for MCT1 and 12 ng of cRNA coding for CAII-WT or a CAII mutant, 3–6 days before the experiment.

Measurement of Intracellular H+ Concentration in Xenopus Oocytes

All measurements were carried out in HEPES-buffered solution (82.5 mm NaCl, 2.5 mm KCl, 1 mm CaCl2, 1 mm MgCl2, 1 mm Na2HPO4, 5 mm HEPES). In lactate-containing saline, NaCl was replaced by an equivalent amount of sodium l-lactate. Application of lactate was always carried out in HEPES-buffered solution at pH 7.0, in the nominal absence of CO2/HCO3−, containing ∼0.008 mm of CO2 from air and hence a HCO3− concentration of less than 0.2 mm. To check for CAII catalytic activity, a short CO2 pulse was applied. For this solution, NaCl was replaced by 10 mm NaHCO3, and the solution was aerated with 5% CO2/95% O2.

For measurement of intracellular H+ concentration and membrane potential, single-barreled microelectrodes were used; the manufacture and application have been described in detail previously (51, 52). Briefly, a borosilicate glass capillary of 1.5 mm in diameter was pulled to a micropipette and was silanized with a drop of 5% tri-N-butylchlorsilane in 99.9% pure carbon tetrachloride, backfilled into the tip. The micropipette was baked for 4.5 min at 450 °C on a hot plate. H+-sensitive mixture (no. 95291; Fluka) was backfilled into the silanized tip and filled up with 0.1 sodium citrate, pH 6.0. To increase the opening of the electrode tip, it was beveled with a jet stream of aluminum powder suspended in H2O. The reference electrode was filled with 3 m KCl. Calibration of the electrodes was carried out in oocyte salines with a pH of 7.0 and 6.4. As described previously (2), optimal pH changes were detected when the electrode was located near the inner surface of the plasma membrane. During all measurements, the oocytes were clamped to a holding potential of −40 mV using an additional microelectrode, filled with 3 m KCl, and connected to an Axoclamp 2B amplifier (Axon Instruments). All experiments were carried out at room temperature (22–25 °C). The measurements were stored digitally using custom made PC software based on the program LabView (National Instruments). The rate of change of the measured [H+]i was analyzed by determining the slope of a linear regression fit using the spreadsheet program OriginPro 8.6 (OriginLab Corporation). Conversion and analysis of the data has been described in detail previously (52).

Calculation and Statistics

Statistical values are presented as means ± S.E. of the mean. For calculation of significance in differences, Student's t test or, if possible, a paired t test was used. In the figures shown, a significance level of p ≤ 0.05 is marked with *, p ≤ 0.01 is marked with **, and p ≤ 0.001 is marked with ***.

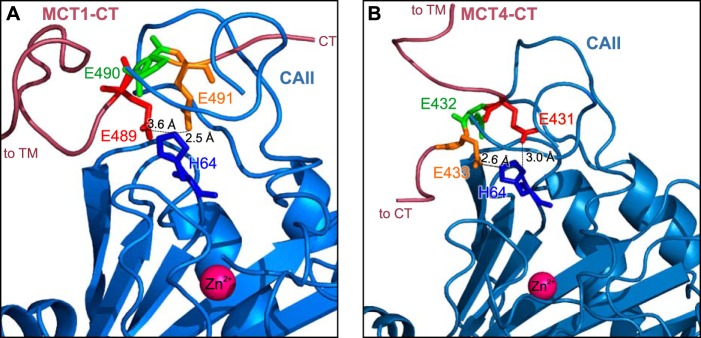

Structural Model of the Binding between MCT1/MCT4 and CAII

The C terminus of MCT1 is predicted to be intrinsically disordered but may adapt secondary structure upon binding CAII and was therefore modeled to form a distorted helix turn helix motif using a leucine zipper (Protein Data Bank code 1A93) as a starting model to facilitate binding to the slightly acidic and hydrophobic faces of CAII. The C terminus of MCT4 is based on the model of the MCT1 C terminus, with minor rearrangements to facilitate proper CAII-His64 interactions. CAII is based on the crystal structure of human CAII (Protein Data Bank code 2ILI (53)). Models were created utilizing SWISS Model. Docking of the C terminus of MCT1/MCT4 to CAII was performed using the interactive software COOT (54) and then energy minimizing using the program CNS (55). Graphical representations of the structures were created with MacPyMOL (DeLano Scientific LLC).

RESULTS

Introduction of a CAII-binding Site Allows CAII-mediated Facilitation of MCT2 Transport Activity

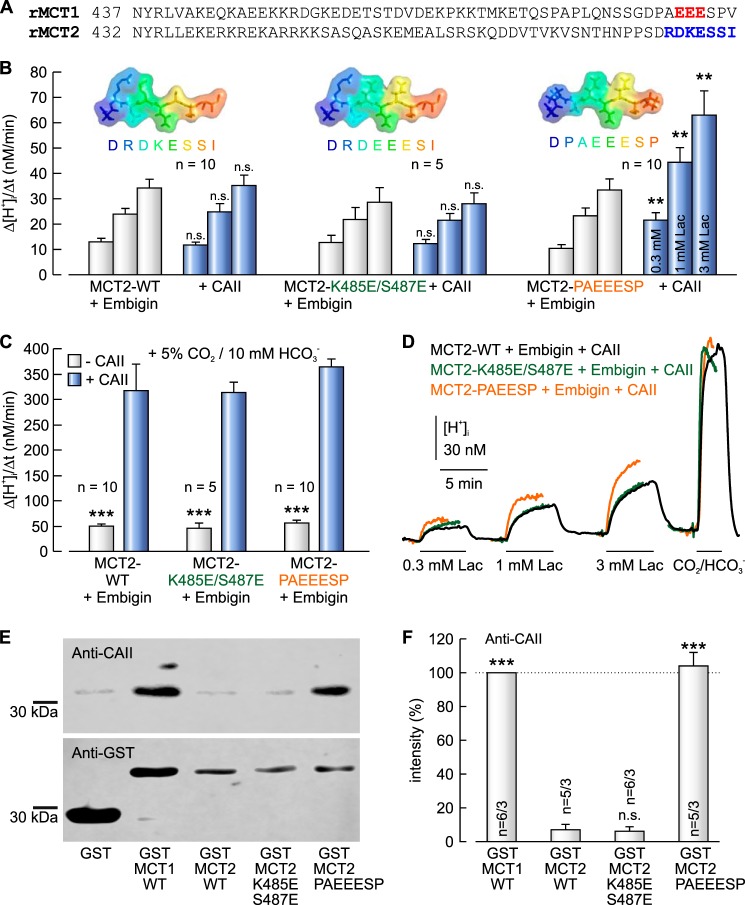

We have previously shown that CAII augments transport activity of MCT1, while leaving transport activity of MCT2 unaltered (42, 43, 45, 46, 49). Although the C terminus of MCT1 contains a CAII binding site (489EEE), MCT2 lacks such a cluster (Fig. 1A). To test the hypothesis that the failure of CAII to enhance MCT2 transport activity is due to the lack of an appropriate CAII-binding site in the MCT2-C terminus, we introduced a putative CAII-binding site into the C terminus of MCT2. Therefore we replaced lysine 485 and serine 487 by glutamate (MCT2-K485E/S487E), which would create a putative CAII-binding site (485EEE) at a similar position as found in MCT1 (489EEE). MCT2-WT and MCT2-K485E/S487E, respectively, were coexpressed together with their chaperone embigin (GP70) in Xenopus oocytes, either with or without 50 ng CAII protein injected. MCT2 transport activity was determined by measuring the rate of rise in intracellular H+ concentration (Δ[H+]i/Δt) during application of 0.3, 1, and 3 mm lactate, respectively, in HEPES-buffered, nominal CO2/HCO3−-free solution (Fig. 1, B and D). Injection of CAII did not result in an increase in MCT2 transport function, neither in MCT2-WT nor in MCT2-K485E/S487E, carrying the putative CAII binding site (Fig. 1B). However, in MCT2-K485E/S487E the putative binding site 485EEE is surrounded by polar or bulky amino acids (see inset in Fig. 1B) that are not found at this position in MCT1. To determine whether these amino acids might obscure the CAII-binding site, we exchanged the seven most distal amino acids in the MCT2 C terminus to the corresponding amino acids of the MCT1 C terminus (R483P/D484A/K485E/E486E/S487E/S488S/I489P, MCT2-PAEEESP) and coexpressed the mutant with embigin in Xenopus oocytes. Indeed, injection of CAII increased transport activity of MCT2-PAEEESP by a factor of ∼2, indicating a functional interaction between CAII and the MCT2 mutant (Fig. 1B). Catalytic activity of CAII was controlled in each oocyte by measuring Δ[H+]i/Δt during application of 5% CO2, 10 mm HCO3− at the end of the experiment (Fig. 1D) to confirm successful injection of CAII. In all three batches of oocytes, injection of CAII increased the rate of CO2-induced acidification by a factor of ∼6.5 with no significant difference between the batches (Fig. 1C).

FIGURE 1.

Insertion of a CAII binding site into the C terminus of MCT2 enables functional interaction between MCT2 and CAII. A, protein sequence of the C terminus of rat MCT1 (NP_036848.1) and rat MCT2 (NP_058998.2). The CAII-binding site in MCT1 is in red. The mutated amino acid cluster in MCT2 is in blue. B, rate of rise in intracellular H+ concentration during application of 0.3, 1, and 3 mm lactate in Xenopus oocytes coexpressing MCT2-WT, MCT2-K485E/S487E, and MCT2-R483P/D484A/K485E/S487E/I489P (MCT2-PAEEESP), respectively, and embigin, with and without injected CAII protein. The asterisks above the bars with CAII refer to the corresponding values without CAII. The inset gives a graphical representation of the protein sequence of the last eight amino acids of the MCT2 constructs used in the experiments. C, rate of rise in intracellular H+ concentration during application of 5% CO2, 10 mm HCO3− in Xenopus oocytes coexpressing MCT2-WT, MCT2-K485E/S487E, and MCT2-PAEEESP, respectively, and embigin, with and without injected CAII protein. The asterisks above the bars without CAII refer to the corresponding values with CAII. D, original recordings of the intracellular H+ concentration in Xenopus oocyte coexpressing MCT2-WT (black trace), MCT2-K485E/S487E (green trace), and MCT2-PAEEESP (orange trace), respectively, and embigin. Cells were injected with 50 ng of CAII protein. MCT2 was activated by application of 0.3, 1, and 3 mm lactate, respectively; catalytic activity of CAII was confirmed by application of 5% CO2, 10 mm HCO3−. E, representative Western blots of CAII (upper blot) and GST (lower blot), respectively. CAII was pulled down with GST, a GST fusion protein of the C terminus of MCT1-WT, MCT2-WT, or a GST fusion protein of a mutant of the MCT2-CT. F, relative intensity of the fluorescent signal of CAII. For every blot, the signals for CAII were normalized to the corresponding signals for GST-MCT1-WT. Each individual signal for CAII was normalized to the intensity of the signal for GST. The asterisks above the bars refer to GST-MCT2-WT. n is given as the number of Western blots/number of pulldown experiments.

Binding between CAII and MCT2 was tested by pulldown of CAII with GST fusion proteins of the C termini of MCT2-WT, MCT2-K485E/S487E, and MCT2-PAEEESP, respectively (Fig. 1E). A GST fusion protein of the C terminus of MCT1 was used as positive control. To overcome variations in the signal intensity between different blots, signal intensity of each band for CAII was normalized to the signal intensity of the band from the pulldown of CAII with GST-MCT1-WT. To account for variations in the amount of GST fusion protein, each normalized signal for CAII was divided by the corresponding, normalized signal for GST. Pulldown of CAII with GST-MCT2-WT resulted in a very weak signal for CAII (Fig. 1F). Mutation of Lys485 and Ser487 to glutamic acid (GST-MCT2-K485E/S487E) did not increase the amount of captured CAII, whereas mutation of the last seven amino acids of the MCT2 C terminus to the corresponding amino acids in MCT1 (GST-MCT2-PAEEESP) resulted in a significant increase in the amount of captured CAII, which indicates direct binding of CAII to MCT2-PAEEESP. These data indicate that the mere presence of an appropriate acidic amino acid cluster within the C terminus of the transport protein is not sufficient to mediate binding of CAII but that the amino acids surrounding this acidic cluster must allow free access of the binding site to CAII.

CAII-mediated Augmentation of MCT4 Transport Activity Requires Physical Interaction between CAII and the MCT4 C Terminus

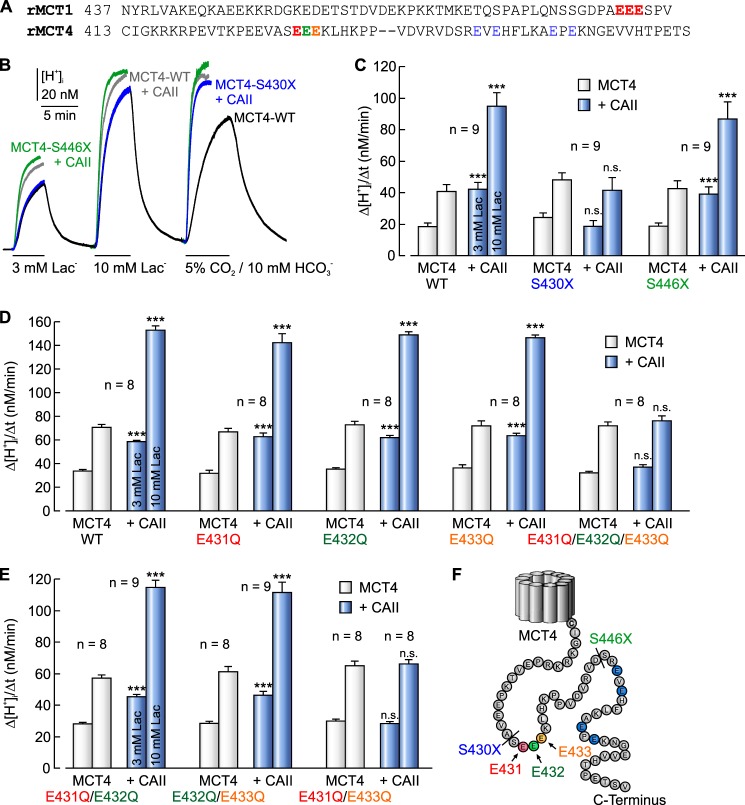

In MCT1, binding to CAII is mediated by the two glutamic acid residues Glu489 and Glu491 in the C terminus of the transporter (Fig. 2A), which is mandatory for the CAII-mediated augmentation in MCT1 transport activity (49). The C terminus of rat MCT4 contains three similar clusters in which two glutamic acid residues are separated by one amino acid: 431EEE, 448EVE, and 456EPE (Fig. 2, A and F). To analyze which one of these three clusters is required for the functional interaction between MCT4 and CAII, we created two truncation mutants of MCT4, missing either all three potential binding sites (MCT4-S430X) or missing only 448EVE and 456EPE (MCT4-S446X). Either MCT4-WT or one of the two truncated mutants was expressed in Xenopus oocytes in the absence or presence of 50 ng of CAII protein. MCT4 transport activity was determined by measuring changes in intracellular H+ concentration during application of 3 and 10 mm lactate in HEPES-buffered, nominal CO2/HCO3−-free solution (Fig. 2B). Injection of CAII enhanced transport activity of MCT4-WT by a factor of ∼2, as determined by Δ[H+]i/Δt during application of lactate (Fig. 2C). Truncation of the MCT4 C terminus at position 430 (MCT4-S430X; removal of all three potential binding sites) resulted in a complete loss of the CAII-mediated augmentation in MCT4 transport activity (Fig. 2C). In contrast, truncation of the MCT4 C terminus at position 446 (MCT4-S446X; removal of 448EVE and 456EPE) had no effect on the CAII-induced augmentation in MCT4 transport activity (Fig. 2C). Transport activity of MCT4 itself in the absence of CAII was not altered by truncation of the C terminus (Fig. 2C, gray bars). These data indicate that functional interaction between MCT4 and CAII is mediated by an amino acid cluster located between Ser430 and Ser446 in the MCT4 C terminus, most likely the glutamic acid cluster 431EEE.

FIGURE 2.

Functional interaction between MCT4 and CAII requires a cluster of glutamic acid residues in the C-terminal tail of MCT4. A, protein sequence of the C terminus of rat MCT1 (NP_036848.1) and rat MCT4 (NP_110461.1). CAII binding sites are in red. B, original recordings of the intracellular H+ concentration in a MCT4-WT-expressing Xenopus oocyte (black trace) and in oocytes expressing MCT4-WT (gray traces), MCT4-S430X (blue traces), and MCT4-S446X (green traces), respectively, injected with 50 ng of CAII protein. MCT4 was activated by application of 3 and 10 mm lactate; catalytic activity of CAII was confirmed by application of 5% CO2, 10 mm HCO3−. C, rate of rise in intracellular H+ concentration during application of 3 and 10 mm lactate in Xenopus oocytes expressing MCT4-WT, MCT4-S430X, and MCT4-S446X with and without injected CAII protein. The asterisks above the bars with CAII refer to the corresponding values without CAII. D and E, rate of rise in intracellular H+ concentration during application of 3 and 10 mm lactate in Xenopus oocytes expressing MCT4-WT and MCT4 with different mutations in the C terminus, with and without injected CAII protein. The asterisks above the bars with CAII refer to the corresponding values without CAII. F, protein sequence of MCT4 C terminus. The truncation sites are labeled with a dash, and the single-site mutations are labeled in color.

To further analyze which glutamic acid residues within this cluster are required for functional interaction between MCT4 and CAII, we replaced the three glutamic acid residues Glu431–Glu433 by glutamine in any possible combination and expressed the mutants in Xenopus oocytes with and without CAII (Fig. 2, D and E). Single replacement of any glutamic acid residue by glutamine (MCT4-E431Q, MCT4-E432Q, and MCT4-E433Q, respectively) had no effect on the CAII-mediated augmentation in MCT4 transport activity. Injection of CAII induced an increase in Δ[H+]i/Δt by a factor of ∼2 in all mutants, as observed for MCT4-WT (Fig. 2D). However, simultaneous replacement of all three glutamic acid residues by glutamine (MCT4-E431Q/E432Q/E433Q) completely abolished CAII-induced augmentation in MCT4 transport activity (Fig. 2D). Replacement of the two glutamic acid residues by glutamine at the rim of the cluster (MCT4-E431Q/E433Q) also abolished CAII-induced augmentation in MCT4 transport activity, whereas replacing either one of the flanking glutamic acid residues and the glutamic acid residue in the middle of the cluster by glutamine (MCT4-E431Q/E432Q and MCT4-E432Q/E433Q, respectively) had no effect on the CAII-induced augmentation in MCT4 activity (Fig. 2E). These data indicate that at least one of the two glutamic acid residues Glu431 and Glu433 in the MCT4 C terminus is required for the functional interaction between MCT4 and CAII. Catalytic activity of CAII was controlled in each oocyte by measuring Δ[H+]i/Δt during application of 5% CO2, 10 mm HCO3− at the end of the experiment. Fig. 2B shows example traces of MCT4-WT (black trace, third pulse) as example for a non-CAII-injected oocyte, and traces of MCT4-WT + CAII (gray trace, third pulse), MCT4-S446X + CAII (green trace, third pulse), and MCT4-S430X + CAII (blue trace, third pulse) as examples for CAII-injected oocytes. In non-CAII-injected oocytes Δ[H+]i/Δt varied between 27.0 ± 1.0 nm/min and 30.8 ± 1.4 nm/min, whereas Δ[H+]i/Δt in CAII-injected cells varied between 163.4 ± 5.4 nm/min and 199.9 ± 12.4 nm/min (data not shown). No statistical differences were found between the batches, indicating that all batches of oocytes were injected with approximately the same amount of catalytically active CAII protein.

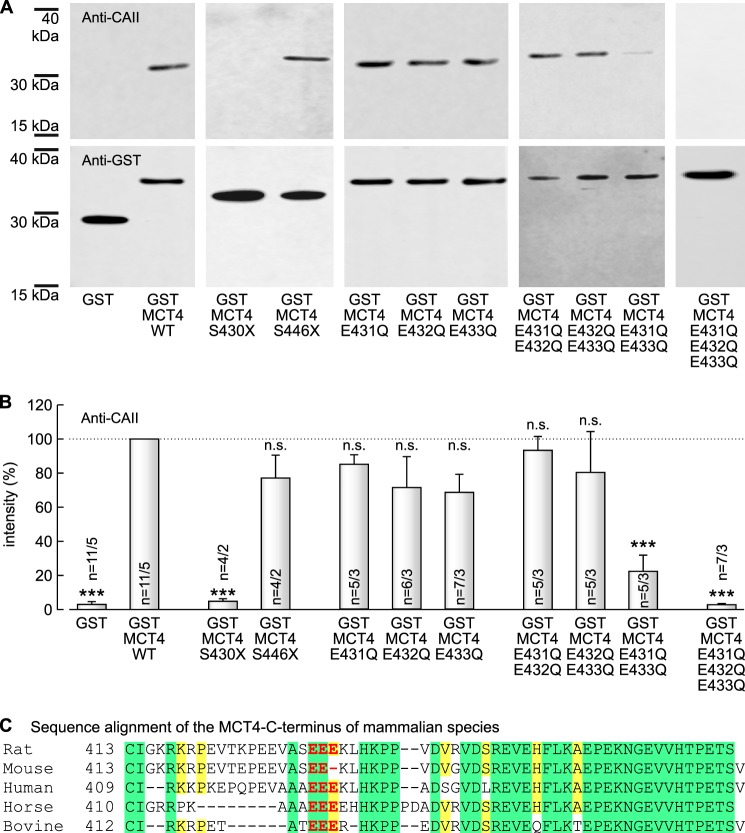

To test whether CAII binds to the C terminus of MCT4, we pulled down CAII from lysates of CAII-expressing Xenopus oocytes with GST fusion proteins of the MCT4 C terminus, bound to agarose beads. The amount of captured CAII was quantified by Western blot analysis (Fig. 3A, upper row). To overcome variations in the signal intensity between different blots, signal intensity of each band for CAII was normalized to the signal intensity of the band from the pulldown of CAII with GST-MCT4-WT. To account for variations in the amount of GST fusion protein, each normalized signal for CAII was divided by the corresponding, normalized signal for GST. Pulldown of CAII with a GST fusion protein of the full-length C terminus of MCT4 (GST-MCT4-WT) resulted in a robust signal for CAII on the Western blot, whereas pulldown of CAII with GST alone resulted in almost no signal for CAII (3.0 ± 1.6% of the signal achieved with GST-MCT4-WT), indicating direct binding of CAII to the C terminus of MCT4, but not to GST (Fig. 3B). Truncation of the C terminus at position 430 (GST-MCT4-S430X) resulted in vast reduction of the signal to 4.8 ± 1.5% (as compared with GST-MCT4-WT), whereas truncation at position 446 (GST-MCT4-S446X) had no significant effect on the amount of captured CAII (Fig. 3B). Single replacement of any glutamic acid residue by glutamine (GST-MCT4-E431Q, GST-MCT4-E432Q, and GST-MCT4-E433Q, respectively), as well as replacing either one of the flanking glutamic acid residues and the glutamic acid residue in the middle of the cluster by glutamine (GST-MCT4-E431Q/E432Q and GST-MCT4-E432Q/E433Q, respectively) also showed no significant effect on the amount of precipitated CAII (Fig. 3B). In contrast to that, replacement of the two glutamic acid residues at the rim of the cluster by glutamine (GST-MCT4-E431Q/E433Q), as well as simultaneous replacement of all three glutamic acid residues by glutamine (GST-MCT4-E431Q/E432Q/E433Q), led to a significant reduction in the amount of captured CAII (Fig. 3B). These data indicate that CAII binds to the C terminus of MCT4 and that at least one of the two glutamic acid residues Glu431 and Glu433 within the MCT4 C terminus is required for the binding.

FIGURE 3.

CAII binds to the C terminus of MCT4. A, representative Western blots of CAII (upper row) and GST (lower row), respectively. CAII was pulled down with GST, a GST fusion protein of the C terminus of MCT4-WT or a GST fusion protein of a mutant of the MCT4-CT. B, relative intensity of the fluorescent signal of CAII. For every blot, the signals for CAII were normalized to the corresponding signals for GST-MCT4-WT. Each individual signal for CAII was normalized to the intensity of the signal for GST. The asterisks above the bars refer to GST-MCT4-WT. n is given as number of Western blots/number of pulldown experiments. C, protein sequence alignment of the C terminus of MCT4 from rat (NP_110461.1), mouse (NP_001033742.1), human (NP_001193880.1), horse (NP_001139004.1), and bovine (NP_001103450.1). Amino acids conserved above all aligned sequences are colored in green, and amino acids that are conserved in four of the five species are colored in yellow. The CAII binding site is colored in red. The alignment was created with Protein BLAST (NCBI).

Assuming that a CAII-binding site in MCT4 should be conserved along different mammalian species, we aligned the protein sequence of the MCT4 C terminus of the five mammalian species analyzed so far (Fig. 3C). Indeed the binding site was found to be conserved along rat (431EEE), human (425EEE), horse (420EEE), and bovine (422EEE). Only in mouse was the most distal glutamic acid residue missing (431EE-), leaving only one glutamic acid residue (Glu431) that would mediate binding of CAII.

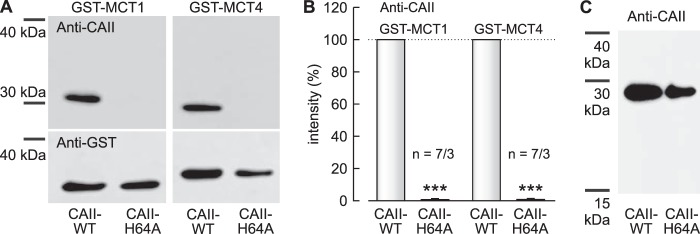

MCT1 and MCT4 Bind to CAII Histidine 64

Previous studies have shown that CAII-His64 is crucial for CAII-mediated increase in transport activity of MCT1 and MCT4, because exchange of His64 by alanine resulted in the loss of CAII-mediated facilitation of transport activity (48). To test whether binding between MCT1/4 and CAII is mediated by His64 in CAII, we pulled down CAII-WT or CAII-H64A with GST-MCT1 and GST-MCT4, respectively (Fig. 4A). Although pulldown of CAII-WT with GST-MCT1 and GST-MCT4 resulted in a robust signal for CAII, virtually no signal could be detected when CAII-H64A was pulled down with GST-MCT1 or GST-MCT4 (Fig. 4B). To make sure that the antibody used for detection of CAII in the pulldown experiment is able to recognize CAII-H64A, we directly blotted lysates of Xenopus oocytes expressing CAII-WT and CAII-H64A, respectively, and stained for CAII using the same antibody as used for CAII detection after the pulldown (Fig. 4C). The plot showed robust signals both for CAII-WT and CAII-H64A, indicating that CAII-H64A can be recognized by the antibody. These results indicate that binding of MCT1 and MCT4 to CAII is likely mediated by CAII-His64.

FIGURE 4.

Histidine 64 in CAII is required for binding of CAII to MCT1 and MCT4. A, representative Western blots for CAII (upper row) and GST (lower row), respectively. CAII-WT or CAII-H64A was pulled down with a GST fusion protein of the C terminus of MCT1-WT or the C terminus of MCT4-WT. B, relative intensity of the fluorescent signal of CAII. For every blot, the signal for CAII-H64A was normalized to the corresponding signal for CAII-WT. Each individual signal for CAII was normalized to the intensity of the signal for GST. The asterisks above the bars for CAII-H64A refer to the corresponding values for CAII-WT. n is given as number of Western blots/number of pulldown experiments. C, representative Western blot for CAII from lysates of Xenopus oocytes, expressing CAII-WT or CAII-H64A.

DISCUSSION

The present study shows that introduction of a CAII-binding site into the C terminus of MCT2 induces CAII-mediated augmentation in MCT2 activity. However, binding and functional interaction could only be achieved when the ambient amino acids were arranged in a fashion that allowed access of the introduced binding site to CAII.

We have previously shown that CAII facilitates transport activity of MCT1, but not MCT2, when the proteins are heterologously expressed in Xenopus oocytes (42, 43, 45–49). Facilitation of MCT1 transport function has been found to be independent of the catalytic activity of the enzyme (42, 43) but required both the intramolecular H+ shuttle of CAII (CAII-His64) (48) and the CAII-binding site 489EEE in the C terminus of MCT1 (49). This led to the conclusion that CAII, directly bound to the transporter, can act as a H+-collecting/distributing antenna, which shuttles protons between transporter and surrounding protonatable residues to support proton/lactate cotransport (48). The requirement for H+-collecting antennae has been proposed for H+ cotransporters such as MCTs, whose substrate is present at very low concentrations (56). By modeling intracellular diffusion of ions following Brownian movement, the authors found that transporters that utilize substrates like Ca2+ or H+, which are available in the cell only at very low concentrations, show experimental rates of transport that are considerably faster than the rates at which the aqueous phase may possibly feed their binding sites. From this paradoxical finding the authors concluded that Ca2+ and H+ transporters do not extract their substrates directly from the bulk cytosol but from an intermediate “harvesting” compartment located between the aqueous phase and the transport site (56), which in the case of MCTs might be CAII. An efficient proton transfer requires close proximity between transporter and enzyme. Therefore, the failure of CAII to increase MCT2 transport activity was attributed to the lack of an appropriate CAII binding site in the C terminus of MCT2. Indeed, the present study shows no binding between CAII and the C terminus of MCT2-WT. To investigate whether introduction of a CAII-binding site into the C terminus of MCT2 might induce facilitation of MCT2 transport activity by CAII, we first introduced a cluster of three glutamic acid residues (485EEE) into the C terminus of MCT2. However, although this potential binding cluster was located at the analogous position of the CAII-binding cluster in MCT1 (489EEE), neither binding of MCT2 to CAII nor CAII-induced facilitation of MCT2 transport activity was observed. Only when the ambient amino acid residues were mutated to the corresponding residues in MCT1 (R483P, D484A, and I489P) was CAII able to bind and facilitate transport activity of MCT2. We speculate that the newly introduced CAII-binding site 485EEE was either obscured by ambient, bulky amino acids or that binding was suppressed because of electrostatic problems, because in the mutant four instead of three acidic amino acid residues are present in a row (DEEE in MCT2-K485E/S487E, instead of AEEE in MCT1-WT). Only when these constraints are removed can the MCT C terminus bind to CAII-His64. This leads to the conclusion that the mere presence of an appropriate acidic amino acid cluster within the C terminus of a transport protein is not sufficient to mediate binding of CAII to this transporter, but that amino acids surrounding this acidic cluster must allow free access of the binding site to CAII and hence functional interaction between these proteins.

We further could show that direct binding between MCT4 and CAII-mediated by Glu431 and Glu433 in the C terminus of MCT4 and CAII-His64 is essential for functional interaction between the two proteins. This arrangement is similar to the binding between MCT1-Glu489/Glu491 and CAII-His64, which allows CAII-mediated facilitation of MCT1 transport activity. Therefore, it appears likely that CAII has to be recruited to the transporter by direct binding to the C-terminal tail of MCT1/4 to be close enough to the transporter pore to establish a proton shuttle between transporter and surrounding protonable residues. A structural model of the binding of CAII to the C terminus of MCT1 and MCT4, respectively, is shown in Fig. 5. The eight most distal amino acids of the MCT1 C terminus (487PAEEESPV) fit well into the surface groove of CAII (Fig. 5A). The side chains of Glu489 and Glu491 of the MCT1 C terminus, which have both been shown to be crucial for binding and functional interaction between MCT1 and CAII (49), point toward the CAII interface within hydrogen bond distance from CAII-His64 in the “out” configuration. In contrast, Glu490 of MCT1-CT points outward to the bulk solvent and would therefore not be involved in the interaction with CAII (Fig. 5A). In contrast to MCT1, the C terminus of MCT4 does not fully cover the surface grove of CAII, but only the three glutamic acid residues 431EEE, which form the CAII binding site, are in close contact with the enzyme (Fig. 5B). The side chains of Glu431 and Glu433 of the MCT4 C terminus, which have both been shown to be crucial for binding and functional interaction between MCT4 and CAII, point toward the CAII interface within hydrogen bond distance from CAII-His64 in the “out” configuration. In contrast, Glu432 of MCT4-CT points outward to the bulk solvent and would therefore not be involved in the interaction with CAII (Fig. 5B).

FIGURE 5.

Structural model of the binding between MCT1/4 and CAII. A, cartoon representation of the MCT1-CAII binding site. The amino acids involved in the binding are represented as sticks. MCT1-E489 (red) and MCT1-E491 (orange) can form hydrogen bonds with CAII-His64 (blue), whereas MCT1-E490 (green) points away from the binding site. B, cartoon representation of the MCT4-CAII binding site. The amino acids involved in the binding are represented as sticks. MCT4-E431 (red) and MCT4-E433 (orange) can form hydrogen bonds with CAII-His64 (blue), whereas MCT4-E432 (green) points away from the binding site. A detailed description of the models is given under “Results.”

Although MCT1 and MCT4 each carry a CAII-binding cluster of three glutamic acid residues, in which the two flanking residues are directly involved in binding, several differences between the CAII-binding sites in MCT1 and MCT4 could be observed. Although in MCT1 both flanking glutamic acid residues (Glu489 and Glu491) are required for binding and functional interaction with CAII (49), only one of the two flanking glutamic acid residues (Glu431 or Glu433) in the binding cluster of MCT4 is required for physical and functional interaction with CAII (this study). This difference may indicate a stronger binding of CAII to MCT4 than to MCT1. However, without further analysis of the binding kinetics, this assumption remains speculative.

This work was supported by Stiftung Rheinland-Pfalz für Innovation Grant 961-386261/957 (to H. M. B.) and by the Landesschwerpunkt Membrantransport (to H. M. B. and J. W. D.).

- MCT

- monocarboxylate transporter

- CAII

- carbonic anhydrase II.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bröer S., Rahman B., Pellegri G., Pellerin L., Martin J. L., Verleysdonk S., Hamprecht B., Magistretti P. J. (1997) Comparison of lactate transport in astroglial cells and monocarboxylate transporter 1 (MCT 1) expressing Xenopus laevis oocytes: expression of two different monocarboxylate transporters in astroglial cells and neurons. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 30096–30102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bröer S., Schneider H.-P., Bröer A., Rahman B., Hamprecht B., Deitmer J. W. (1998) Characterization of the monocarboxylate transporter 1 expressed in Xenopus laevis oocytes by changes in cytosolic pH. Biochem. J. 333, 167–174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Halestrap A. P., Price N. T. (1999) The proton-linked monocarboxylate transporter (MCT) family: structure, function and regulation. Biochem. J. 343, 281–299 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Halestrap A. P., Meredith D. (2004) The SLC16 gene family: from monocarboxylate transporters (MCTs) to aromatic amino acid transporters and beyond. Pflugers Arch. 447, 619–628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Halestrap A. P. (2013) The SLC16 gene family: structure, role and regulation in health and disease. Mol. Aspects Med. 34, 337–349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Garcia C. K., Brown M. S., Pathak R. K., Goldstein J. L. (1995) cDNA cloning of MCT2, a second monocarboxylate transporter expressed in different cells than MCT1. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 1843–1849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Jackson V. N., Halestrap A. P. (1996) The kinetics, substrate, and inhibitor specificity of the monocarboxylate (lactate) transporter of rat liver cells determined using the fluorescent intracellular pH indicator, 2′,7′-bis(carboxyethyl)-5(6)-carboxyfluorescein. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 861-868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jackson V. N., Price N. T., Carpenter L., Halestrap A. P. (1997) Cloning of the monocarboxylate transporter isoform MCT2 from rat testis provides evidence that expression in tissues is species-specific and may involve post-transcriptional regulation. Biochem. J. 324, 447–453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bröer S., Bröer A., Schneider H.-P, Stegen C., Halestrap A. P., Deitmer J. W. (1999) Characterization of the high-affinity monocarboxylate transporter MCT2 in Xenopus laevis oocytes. Biochem. J. 341, 529–535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pellerin L., Pellegri G., Bittar P. G., Charnay Y., Bouras C., Martin J. L., Stella N., Magistretti P. J. (1998) Evidence supporting the existence of an activity-dependent astrocyte-neuron lactate shuttle. Dev. Neurosci. 20, 291–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pellerin L., Pellegri G., Martin J. L., Magistretti P. J. (1998) Expression of monocarboxylate transporter mRNAs in mouse brain: support for a distinct role of lactate as an energy substrate for the neonatal vs. adult brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 3990–3995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bergersen L., Waerhaug O., Helm J., Thomas M., Laake P., Davies A. J., Wilson M. C., Halestrap A. P., Ottersen O. P. (2001) A novel postsynaptic density protein: the monocarboxylate transporter MCT2 is co-localized with δ-glutamate receptors in postsynaptic densities of parallel fiber-Purkinje cell synapses. Exp. Brain Res. 136, 523–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pierre K., Pellerin L. (2005) Monocarboxylate transporters in the central nervous system: distribution, regulation and function. J. Neurochem. 94, 1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yoon H., Fanelli A., Grollman E. F., Philp N. J. (1997) Identification of a unique monocarboxylate transporter (MCT3) in retinal pigment epithelium. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 234, 90–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Philp N. J., Yoon H., Grollman E. F. (1998) Monocarboxylate transporter MCT1 is located in the apical membrane and MCT3 in the basal membrane of rat RPE. Am. J. Physiol. 274, R1824–R1828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Philp N. J., Yoon H., Lombardi L. (2001) Mouse MCT3 gene is expressed preferentially in retinal pigment and choroid plexus epithelia. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 280, C1319–C1326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Grollman E. F., Philp N. J., McPhie P., Ward R. D., Sauer B. (2000) Determination of transport kinetics of chick MCT3 monocarboxylate transporter from retinal pigment epithelium by expression in genetically modified yeast. Biochemistry 39, 9351–9357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dimmer K. S., Friedrich B., Lang F., Deitmer J. W., Bröer S. (2000) The low-affinity monocarboxylate transporter MCT4 is adapted to the export of lactate in highly glycolytic cells. Biochem. J. 350, 219–227 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pinheiro C., Reis R. M., Ricardo S., Longatto-Filho A., Schmitt F., Baltazar F. (2010) Expression of monocarboxylate transporters 1, 2, and 4 in human tumours and their association with CD147 and CD44. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2010, 427694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pinheiro C., Longatto-Filho A., Azevedo-Silva J., Casal M., Schmitt F. C., Baltazar F. (2012) Role of monocarboxylate transporters in human cancers: state of the art. J. Bioenerg. Biomembr. 44, 127–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wilson M. C., Meredith D., Fox J. E., Manoharan C., Davies A. J., Halestrap A. P. (2005) Basigin (CD147) is the target for organomercurial inhibition of monocarboxylate transporter isoforms 1 and 4: the ancillary protein for the insensitive MCT2 is EMBIGIN (gp70). J. Biol. Chem. 280, 27213–27221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wilson M. C., Meredith D., Bunnun C., Sessions R. B., Halestrap A. P. (2009) Studies on the DIDS-binding site of monocarboxylate transporter 1 suggest a homology model of the open conformation and a plausible translocation cycle. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 20011–20021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Maren T. H. (1967) Carbonic anhydrase: chemistry, physiology, and inhibition. Physiol. Rev. 47, 595–781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Frost S. C. (2014) Physiological functions of the alpha class of carbonic anhydrases. In Sub-cellular Biochemistry (Frost S. C., McKenna R., eds) pp. 9–30, Springer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kifor G., Toon M. R., Janoshazi A., Solomon A. K. (1993) Interaction between red cell membrane band 3 and cytosolic carbonic anhydrase. J. Membr. Biol. 134, 169–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Vince J. W., Reithmeier R. A. (1998) Carbonic anhydrase II binds to the carboxyl terminus of human band 3, the erythrocyte C1−/HCO3− exchanger. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 28430–28437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Vince J. W., Reithmeier R. A. (2000) Identification of the carbonic anhydrase II binding site in the Cl−/HCO3− anion exchanger AE1. Biochemistry 39, 5527–5533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Vince J. W., Carlsson U., Reithmeier R. A. (2000) Localization of the Cl−/HCO3− anion exchanger binding site to the amino-terminal region of carbonic anhydrase II. Biochemistry 39, 13344–13349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sterling D., Reithmeier R. A., Casey J. R. (2001) A transport metabolon: functional interaction of carbonic anhydrase II and chloride/bicarbonate exchangers. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 47886–47894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Burg M., Green N. (1977) Bicarbonate transport by isolated perfused rabbit proximal convoluted tubules. Am. J. Physiol. 233, F307–F314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sasaki S., Marumo F. (1989) Effects of carbonic anhydrase inhibitors on basolateral base transport of rabbit proximal straight tubule. Am. J. Physiol. 257, F947–F952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Seki G., Frömter E. (1992) Acetazolamide inhibition of basolateral base exit in rabbit renal proximal tubule S2 segment. Pflugers Arch. 422, 60–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gross E., Pushkin A., Abuladze N., Fedotoff O., Kurtz I. (2002) Regulation of the sodium bicarbonate cotransporter kNBC1 function: role of Asp986, Asp988 and kNBC1-carbonic anhydrase II binding. J. Physiol. 544, 679–685 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pushkin A., Abuladze N., Gross E., Newman D., Tatishchev S., Lee I., Fedotoff O., Bondar G., Azimov R., Ngyuen M., Kurtz I. (2004) Molecular mechanism of kNBC1-carbonic anhydrase II interaction in proximal tubule cells. J. Physiol. 559, 55–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Loiselle F. B., Morgan P. E., Alvarez B. V., Casey J. R. (2004) Regulation of the human NBC3 Na+/HCO3− cotransporter by carbonic anhydrase II and PKA. Am. J. Physiol. Cell Physiol. 286, C1423–C1433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Becker H. M., Deitmer J. W. (2007) Carbonic anhydrase II increases the activity of the human electrogenic Na+/HCO3− cotransporter. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 13508–13521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Li X., Alvarez B., Casey J. R., Reithmeier R. A., Fliegel L. (2002) Carbonic anhydrase II binds to and enhances activity of the Na+/H+ exchanger. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 36085–36091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Li X., Liu Y., Alvarez B. V., Casey J. R., Fliegel L. (2006) A novel carbonic anhydrase II binding site regulates NHE1 activity. Biochemistry 45, 2414–2424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Johnson D. E., Casey J. R. (2009) Bicarbonate Transport Metabolons. In Drug Design of Zinc-Enzyme Inhibitors: Functional, Structural, and Disease Applications (Supuran C. T., Winum J.-Y., eds), John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, NJ [Google Scholar]

- 40. Deitmer J. W., Becker H. M. (2013) Transport metabolons with carbonic anhydrases. Front. Physiol. 4, 291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Becker H. M., Klier M., Deitmer J. W. (2014) Carbonic anhydrases and their interplay with acid/base-coupled membrane transporters. In Sub-cellular Biochemistry (Frost S. C., McKenna R., eds) pp. 105–34, Springer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Becker H. M., Hirnet D., Fecher-Trost C., Sültemeyer D., Deitmer J. W. (2005) Transport activity of MCT1 expressed in Xenopus oocytes is increased by interaction with carbonic anhydrase. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 39882–39889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Becker H. M., Deitmer J. W. (2008) Nonenzymatic proton handling by carbonic anhydrase II during H+-lactate cotransport via monocarboxylate transporter 1. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 21655–21667 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Becker H. M., Klier M., Deitmer J. W. (2010) Nonenzymatic augmentation of lactate transport via monocarboxylate transporter isoform 4 by carbonic anhydrase II. J. Membr. Biol. 234, 125–135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Klier M., Schüler C., Halestrap A. P., Sly W. S., Deitmer J. W., Becker H. M. (2011) Transport activity of the high-affinity monocarboxylate transporter MCT2 is enhanced by extracellular carbonic anhydrase IV but not by intracellular carbonic anhydrase II. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 27781–27791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Klier M., Andes F. T., Deitmer J. W., Becker H. M. (2014) Intracellular and extracellular carbonic anhydrases cooperate non-enzymatically to enhance activity of monocarboxylate transporters. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 2765–2775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Almquist J., Lang P., Prätzel-Wolters D., Deitmer J. W., Jirstrand M., Becker H. M. (2010) A kinetic model of the monocarboxylate transporter MCT1 and its interaction with carbonic anhydrase II. J. Comput. Sci. Syst. Biol. 03, 107–116 [Google Scholar]

- 48. Becker H. M., Klier M., Schüler C., McKenna R., Deitmer J. W. (2011) Intramolecular proton shuttle supports not only catalytic but also noncatalytic function of carbonic anhydrase II. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 3071–3076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Stridh M. H., Alt M. D., Wittmann S., Heidtmann H., Aggarwal M., Riederer B., Seidler U., Wennemuth G., McKenna R., Deitmer J. W., Becker H. M. (2012) Lactate flux in astrocytes is enhanced by a non-catalytic action of carbonic anhydrase II. J. Physiol. 590, 2333–2351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Becker H. M., Bröer S., Deitmer J. W. (2004) Facilitated lactate transport by MCT1 when coexpressed with the sodium bicarbonate cotransporter (NBC) in Xenopus oocytes. Biophys. J. 86, 235–247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Deitmer J. W. (1991) Electrogenic sodium-dependent bicarbonate secretion by glial cells of the leech central nervous system. J. Gen. Physiol. 98, 637–655 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Becker H. M. (2014) Transport of lactate: Characterization of the transporters involved in transport at the plasma membrane by heterologous protein expression on Xenopus oocytes. Neuromethods 90, 25–43 [Google Scholar]

- 53. Fisher S. Z., Maupin C. M., Budayova-Spano M., Govindasamy L., Tu C., Agbandje-McKenna M., Silverman D. N., Voth G. A., McKenna R. (2007) Atomic crystal and molecular dynamics simulation structures of human carbonic anhydrase II: insights into the proton transfer mechanism. Biochemistry 46, 2930–2937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Emsley P., Cowtan K. (2004) Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Brünger A. T., Adams P. D., Clore G. M., DeLano W. L., Gros P., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Jiang J. S., Kuszewski J., Nilges M., Pannu N. S., Read R. J., Rice L. M., Simonson T., Warren G. L. (1998) Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D. Biol Crystallogr. 54, 905–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Martínez C., Kalise D., Barros L. F. (2010) General requirement for harvesting antennae at Ca2+ and H+ channels and transporters. Front. Neuroenergetics 2, 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]