Abstract

Objective:

The aim of this study was to review the current methods of pharmaceutical purchasing by Iranian insurance organizations within the World Bank conceptual framework model so as to provide applicable pharmaceutical resource allocation and purchasing (RAP) arrangements in Iran.

Methods:

This qualitative study was conducted through a qualitative document analysis (QDA), applying the four-step Scott method in document selection, and conducting 20 semi-structured interviews using a triangulation method. Furthermore, the data were analyzed applying five steps framework analysis using Atlas-ti software.

Findings:

The QDA showed that the purchasers face many structural, financing, payment, delivery and service procurement and purchasing challenges. Moreover, the findings of interviews are provided in three sections including demand-side, supply-side and price and incentive regime.

Conclusion:

Localizing RAP arrangements as a World Bank Framework in a developing country like Iran considers the following as the prerequisite for implementing strategic purchasing in pharmaceutical sector: The improvement of accessibility, subsidiary mechanisms, reimbursement of new drugs, rational use, uniform pharmacopeia, best supplier selection, reduction of induced demand and moral hazard, payment reform. It is obvious that for Iran, these customized aspects are more various and detailed than those proposed in a World Bank model for developing countries.

Keywords: Insurance organization, Iran, pharmaceutical, resource allocation and purchasing arrangements, strategic purchasing

INTRODUCTION

Pharmaceuticals are considered to be imperative factors for the proper functioning of health continuum[1] and at the same time, to be accounting for a significant part of health systems cost in developing countries[2] where 50–90% of medicines are paid out of pocket as a share of total health expenditure, and in more than 30 countries with low and middle incomes, per capita public spending on medicine per capita is less than $2 per person.[3] Other statistics show that medicine expenditure per capita in 2006 varied from U.S. $7.61 in low-income countries to U.S. $431.6 in high-income ones. Comparing these statistics with those of 1995 also indicates that spending on medicines per capita has increased in low-income and middle-income countries.[4] While the statistics emphasize the higher medicine cost and its larger share of total health expenditure in developing countries than in developed ones, other studies suggest that there is a high degree of private financing and cumulative procurement with less risk pooling in developing countries.[5]

Iran, as a developing country is no exception. Medicine is so important for the country providing public access to effective and safe medicines at affordable prices is specifically stated in Iran's 20-year prospective national vision document.[6] However, the results of the study on the utilization of health service in 2003 show that most health care costs in public sector were related to pharmaceuticals and devices while 68% of the maximum amount of the direct payment in outpatient department is related to specialist visit, treatment and medicines costs.[7] On the other hand, the trend of visits and medicine costs of basic insurance organizations in the country (2000–2010) shows an increase in the quantity and average of costs and also the total costs on medicines, in a way that referrals to pharmacies among people with armed force insurance had a higher increase than other organizations. Meanwhile, the trend of referring to pharmacy among insured people with Social Security, as the largest basic insurer, increased significantly in 2002. The average cost of medicines in Medical Services Insurance Organization has also been growing substantially compared to other insurance organizations.[8] Other Iranian studies suggest that the elasticity of out of pocket payment variable for medicines was negative among insured people of Social Security Organization from 1999 to 2009, as a 15% increase in the variable had reduced 0.15% of the insured people's average annual visit to a general practitioner.[9]

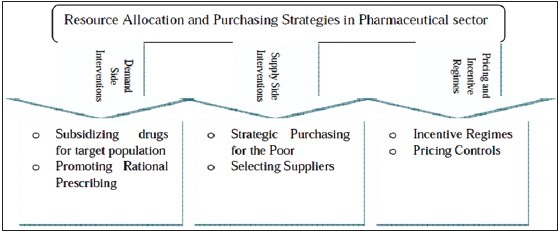

In sum, it seems that although there has been significant increase in the number of people with access to basic pharmaceuticals over the past decade, a large proportion of the population still lacks access to sustainable resources of essential medicines.[10] Increasing the accessibility of medicine is not possible unless through strategic purchase and allocation of adequate resources that require a rational selection of medicines, sustainable financing, affordable prices and a reliable system of drug supply.[3] These strategies, according to the World Bank, are classified as follows: Demand and supply-side interventions, pricing, and incentive regimes.[5]

This study reviewed the current methods of purchasing pharmaceuticals through insurance agencies within the World Bank conceptual framework [Figure 1], and also provided applicable strategies of purchasing in Iranian pharmaceutical system with its increasing accessibility.

Figure 1.

The World Bank Conceptual Framework for RAP. RAP: Resource allocation and purchasing

METHODS

This qualitative study was conducted to present appropriate national strategies such as resource allocation and purchasing (RAP) arrangements for Iranian pharmaceutical sector according to the World Bank's conceptual model [Figure 1], following two operational and methodological phases:

The first phase: Document analysis

The aim of the first phase was to collect the required data for determining the present of pharmaceutical purchasing situation in the country through a qualitative document analysis (QDA) method. In this regard, the relevant documents were included in a paper form from 2007 as the starting point of the fourth national socialeconomical plan focusing on health service providing mechanisms and insurance system correction. The electronic documents were not available due to that absence of integrated and updated data banks in the country. Accordingly, these documents were obtained from various units, especially the Ministry of Health and Medical Education, Food and Drug Organization and the Ministry of Welfare, all as policy makers and health service providers. Moreover, the appropriate documents of four basic and public insurance companies (Social Security Organization, Medical Services Organization, Armed Forces Medical Services Insurance Organization and Imam Khomeini Relief Committee) as the most health care purchasers were studied. The four-step Scott method was employed as a standard method in selecting documents with the following purposes:[11]

Determining the authenticity of documents

This step aims to offer a genuine interpretation of reality or an accurate reading of a particular document. To achieve this aim, after collecting the relevant documents, their authenticity was evaluated in terms of time (from 2007) where the most recent records were employed.

Approving the credibility of documents

Through a peer review, all selected documents were tested in terms of content, content validity and significance and the most valid materials were included.

Indicatory and representative of the data

At this stage, we only selected the documents that clearly indicated the purpose of this study according to a preplanned checklist, explaining the existing methods of pharmaceutical purchasing and their related challenges by the stated insurance companies.

Meaningfulness of the documents

This step focuses on the significance of the documents; therefore, based on the judgment of the research team and the experts of the Ministry of Health and Medical Education, reliable documents officially and publicly provided in the sector were included in this phase.

Applying the previous four-step as a final decision factor for the inclusion of the documents, Microsoft office word was used for the content analysis of the selected documents where it extracted the main concepts and issues related to the present condition of pharmaceutical purchasing in the country. As documents may have some limitations in terms of accuracy and completeness of the data,[12] triangulation method was performed through combining the findings from QDA with interviews in the second phase so as to achieve the best RAP arrangements in Iranian pharmaceutical sector.

The second phase: Interviews

In order to gather the views of experts from the Ministry of Health and Medical Education, Ministry of Welfare and the Food and Drug Organization and four basic public insurance companies as the study population for presenting RAP strategies in pharmaceutical purchasing, 20 semi-structured interviews were conducted with key informants, with each interview defined by the point where data saturation occurred and no new explanations emerged. These 20 experts were chosen purposefully using snow ball sampling.

For data collection, a topic guide was made containing six questions according to three main interventions of the World Bank for pharmaceutical strategic purchasing (demand side interventions, supply-side interventions and Pricing and incentive regime). In order to obtain this topic guide, in addition to the literature review and the findings attained from the first phase, two deep interviews were conducted. So as to ensure the validity and meaningfulness of questions, they were offered to three experts who were not part of the selected respondents; the reliability coefficient of the questions turned out to be 0.87. One week before each session, we provided the necessary coordination with participants in order to hold the interview sessions. The meeting was held in a completely quiet place free from the concerns and preoccupations of the people in their workplace. On average, the length of these sessions was 70 min, and all sessions were recorded by an electronic device, with the permission of the participants. To improve the quality and efficiency of work before the interview sessions, the participants were assured that the data would be confidential, and respondents would remain anonymous. Participants were also allowed to withdraw from the collaboration, anytime they wanted. Additionally, a written consent form was completed and signed by interviewees who voluntarily wanted to collaborate.

Interview records were transcribed immediately after each session. After listening to each recorded file twice, the texts were reviewed and approved by the interviewees so as to ensure the authenticity and accuracy of the rewritten conversation. Data were analyzed through frame work analysis, applying ATLAS-ti Scientific Software Development GmbH with the following five steps:[12]

Familiarization

In this step, a contact and content summary form was developed for each interview.

Identifying a thematic framework

in this stage, the initial thematic framework and codes were developed using the interviews, prior concepts of World Bank as a conceptual model, research questions, and the thematic guide.

Indexing

in this step, the transcriptions were indexed initially by the first author with no conflict of interest. The indexed text was argued and discussed by the research team until a final consensus on their part.

Charting

the interviewees' perspectives were compared applying the analysis chart.

Mapping and interpretation

In the last stage, the relationship between themes and sub-themes were investigated, and all the themes were interpreted.

RESULTS

Findings from the first phase of this study indicated that currently the most important pharmaceutical purchasers in Iranian health system are Social Security Organization, Medical Services Organization (Iranian Health Insurance), Armed Forces Medical Services Insurance Organization and Imam Khomeini Relief Committee, all of which have covered about 90% of the population. However, according to the statistics, there is a 0.5% overlap between insurance agencies and 3.8% of people with complete insurance. Ignoring the overlap between the insurance organizations, the present document analysis indicated that coverage rate will be equal to 86% of the population. Other findings from the first phase of the study indicated that medical services in the country are provided in three types of public, basic and supplementary, yet there is no clear-cut boundary between these types at the moment and the same service is actually purchased at different prices. Furthermore, purchasing basic medicines is a subset of public service. Moreover, regarding basic services, there is a minimum reimbursement of medical services and medicines with different payment ceilings for the same services among insurance organizations.

Other findings related to the first phase of the study and the current situation of the country showed that fund allocation in Iran's health sector is in the form of total annual budget (global), which estimates based on inflation and cost estimation. In addition, several insurance organizations in the country are financed in different ways where some collect funds by capitation, while others by contributions and supportive governmental aids. Findings also determined that currently, insurance organizations passively purchase medicines, in other words, pharmaceuticals are purchased passively by the reimbursement of respective bills presented to the insurance companies, and none of them purchase the most cost-effective and best quality drugs, employing a strategic and wise way.

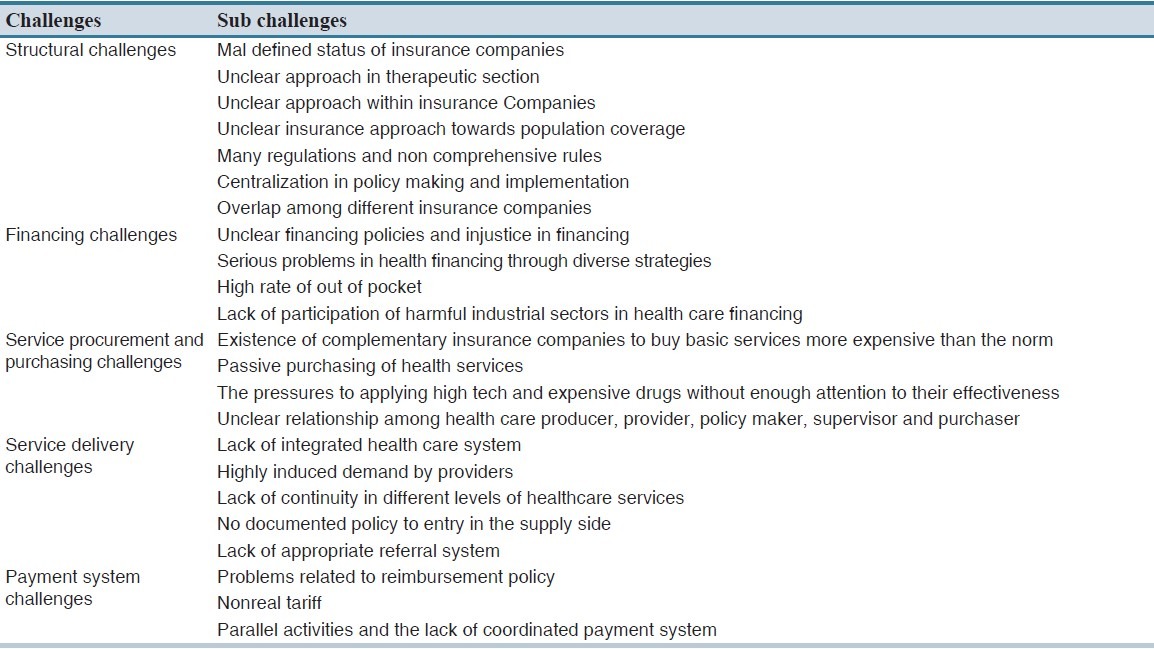

Moreover, after QDA, it was revealed that the current procurement system has several weaknesses including lack of transparency in the relationship among the health care service providers, producers, policy makers, regulators and customers, lack of integrity in the insurer's funds and the existence of supplemental insurance companies, the pressure to use high tech and expensive technologies and medicines, which their cost-effectiveness has not been approved; lack of clear financing policies and inequities in health sector financing, a large amount of out of pocket payment; serious problems in various payment systems for service providers and different payments for the same service, unreal tariffs, parallel activities, lack of a coordinated payment system and so on. As is seen in Table 1, all these challenges are categorized under five different themes as follows: Structural challenges, financing challenges, services procurement and purchasing challenges, service delivery challenges and payment system challenges.

Table 1.

Iranian insurance system challenges

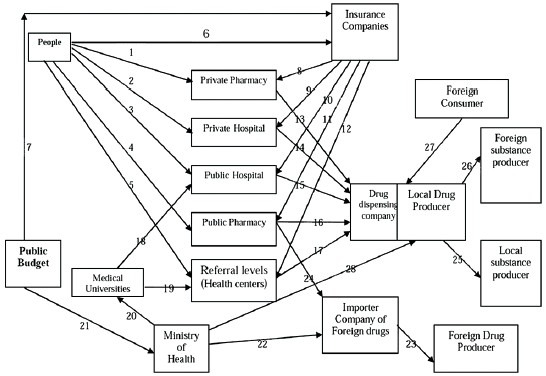

Finally, after analyzing and summarizing all the selected documents in the first phase, the present Iranian transaction and purchasing flow chart was achieved and is demonstrated in Figure 2. As can be seen from the figure, 28 paths are diagnosed for retail or wholesale drug supply. Insurance companies, as the main pharmaceutical purchasers, purchase medicines from private or public pharmacies, dispensing companies, private or public hospitals, health centers, therapeutic centers affiliated with universities of medical sciences and ministry of health and so on using premium and public budget, all indicating a passive mechanism for pharmaceutical purchasing in the country.

Figure 2.

The present Iranian transaction and purchasing flow chart

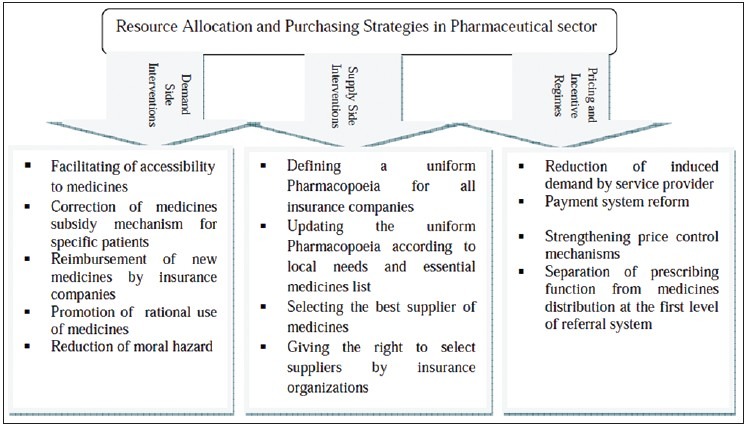

In the second phase of the study, based on the report of the interviewing key informants, pharmaceutical RAP arrangements by insurance organizations were provided within the proposed model of World Bank as follows:

Demand-side interventions

Participants in the study pointed out four main areas of demand-side intervention including.

Facilitating the access to medicines

The respondents pointed to the economic, geographic and socio-cultural access as important mechanisms. One participant stated: “In a country like Iran, socio-cultural access is as important as economic and geographic access. Unfortunately, people keep medicines at home, and this may affect the amount and method of medicine consumption and demand patterns” (P3) (P stands for Participants). On the other hand, one participant stated: “Family medicine and rural health insurance programs started in 2005 would be a good strategy to ensure geographical access to essential medicines” (P13).

Correction of medicine subsidy mechanism for patients with special disease

In Iran, certain diseases such as cancers, hemophilia, thalassemia multiple sclerosis, and liver-related diseases are considered to be specific diseases. Subsidies for the medicines related to such maladies, which are the most expensive pharmaceuticals, used to be provided for the manufacturer for domestic medicines or allocated for imported medicines so far. This process has already stopped, and subsidies are directly paid to the patient. In this regard, one interviewee stated: “Providing the patient with subsidies may cause swelling in the market and allocating money to the cost of nonmedical consumption by patient, which makes the situation even worse” (P8). As far as the correction method of subsidies provision is concerned, the interviewees considered subsidies provision for insurance organizations as a corrective mechanism; for instance “…subsidies should not be allocated to medicines any more. We witnessed the medicines traffic from inside the country overseas, due to the lower cost of medicines. Instead of allocating subsidies to medicines, they should be given to the insurer organization as service purchaser in the shape of smart card or etc.” (P2) or “subsidies should neither be allocated to medicines, nor patients because both create problems; subsidies should be given to insurer organization by government” (P18).

Reimbursement of new medicines by insurance companies

The interviewees mentioned providing integrated instructions for reimbursing new medicines by insurance based on cost-effectiveness studies as well as budget impact analysis. One interviewee believed: “… It is essential to develop the same inclusion criteria in reimbursing new medicines for all insurance organizations based on health technology assessment studies …” (P5). Furthermore, applying scientific methods such as budget impact analysis (BIA) may help remove certain medicines from reimbursement, and add other medications to the list. For instance:“… The exclusion of certain reimbursed medicines, such as antibiotics that currently account for the largest share of payments, may create an opportunity for new medicine reimbursement” (P11).

Promoting rational use of medicines

According to the participants, prescription and rational consumption are closely related to each other, for example: “The absence of a correct rational use consumption and prescription of medicines, particularly in the case of antibiotics may lead to drug resistance” (P7). Meanwhile, paying attention to correcting public beliefs and providing effective training are necessary. The respondents pointed out strategies to encourage rational use and prescription of medicines including: Effective training through media and face to face training in rural areas, providing adequate supervision on pharmacies activities so as to avoid the sale of nonprescribed medicines, and encouraging the use of alternative medicines (generic scheme). In this regard, one interviewee stated: “The simultaneous application of the four categories of educational, managerial, regulatory and financial strategies is a matter of great importance when it comes to promoting proper medicine consumption” (P18).

Reduction of moral hazard

The respondents pointed out that the moral hazard may occur and lead to excessive use of services by insured patients. In line with this, “moral hazard related to medicines is high especially among the insured people of Armed forces Insurance Organization, because this organization has a wide reimbursement policy for medicines. Furthermore, the risk of insurance card abuse should also be considered as a significant factor” (P20).

Supply-side interventions

Defining a uniform pharmacopeia for all insurance companies

Currently, there is no uniform pharmacopeia (medicine list) for all insurance organizations in the country, and the list varies depending on the insurance organizations. Besides, price is the only factor affecting insurance payment for medicines, and other factors such as quality are not taken into account: “In the case where there are medicines with multiple brands in the market, the lowest price is the sole basis of acceptance by insurance organizations, and this is where the parameters of quality and efficacy are neglected” (P14).

Updating a uniform Pharmacopeia according to local needs and essential medicine list

The cost-effectiveness of medicines in society and the related analysis of population subgroups based on their income deciles are of great importance. In this regard: “Medicines in the list must have a minimum quality standard. This issue is crucial especially for poor people, because they cannot afford better medicines that are not in the list” (P8). On the other hand, it is very important for developing countries to confirm World Health Organization medicines list according to its local needs and especially in accordance with the integrated pharmacopeia.

Selecting the best medicine supplier

At the moment, one of the most important problems in the country is that despite the existing approved tariff, service purchasing is performed by governmental agencies from private sectors at different prices. This, in turn, increases injustice and isolates the government from the people. Therefore, selecting the best supplier of medicines is obviously of great importance: “There are several suppliers of medicines in Iran: Domestic manufacturers, public or private companies, private companies importing medicines as wholesalers and public or private pharmacies as retailers. However, what should be considered is medicine trafficking in the free market” (P5). Moreover, the quality of medicines purchased in Iran's pharmaceutical market is of great importance: “Whether the quality of generic medicines with the same name produced by different manufacturers is the same or not, the quality of medicines imported from China or India is absolutely poor” (P16). As such, government has an important role on behalf of society to guarantee the quality of products that are released in the market.

Giving right to insurance organizations to select suppliers

The basic requirement of this is purchaser's ability to choose between providers through legal and administrative procedures. The whole process is feasible only through contracts within the framework of laws and regulations concerning buyer (insurer organization) and medicine dealers and suppliers.

Pricing and incentive regime

Reducing the induced demand of service providers

Service providers' induced demand occurs due to the inherent problem of information asymmetry in the health sector. In this regard, the interviewees stated: “Physicians prescribe more medicines for insured patients and insurance organizations' controlling increases the number of medicines prescribed by the physician” (P1)? Furthermore, “doctors typically prescribe foreign brand medicines to the patient reimbursed by supplemental insurance …” (P6).

Payment system reform

According to the participants' point of view, payment system must enhance the efficiency of healthcare system, reduce the cost and lead to quality achievement. Moreover, its implementation must be simple. In other words, incentives in payment system may have an impact on efficiency and equity in medicine consumption. In Iran, current methods of purchasing medicines for patients are refundable fees for medicines covered by supplemental insurance and out of pocket payment for other medicines. In addition, the method of directly paying the provider is on the basis of the fee for service and sometimes fixed budget. However, the interviewees emphasized a per capita system: “In a per capita payment system, the insured person seeks an early treatment, thus the disease can be treated in the early-stages and with cheaper medicines…” (P10). Moreover, a diagnostic related group was another payment system recommended by the participants for pharmaceutical purchasing.

Strengthening price control mechanisms

Participants mentioned important mechanisms to control medicine prices in the market including; increasing the competition, avoiding monopoly and purchasing generic medicines. Furthermore, negotiating and working out an agreement with investors and manufacturers so as to achieve optimal cost, and reasonable profit margin was considered as another mechanism to control prices. Finally, the participants highlighted that competition and regulation are the most important motivational interventions among price control mechanisms.

Separating prescribing function from medicine distribution at the first level of referral system

Combining the roles of the prescriber and the distributor of medicines in any form and time may increase medicine utilization. In Iran's current healthcare system, pharmacists and pharmacy staff are not allowed to prescribe medication in urban areas, therefore, they only sell the medicines prescribed by physicians.[13,14] But at the first level of the network system in rural areas (health house and rural health centers), these roles have been combined, which may increase medicine consumption among rural people.

Figure 3 presents the results of the interview analysis as proposed mechanisms for RAP arrangements in Iran's pharmaceutical system based on World Bank model.

Figure 3.

Proposed RAP arrangements. RAP: Resource allocation and purchasing

DISCUSSION

Based on the study findings, at the moment, insurance organizations passively purchase medicines, and the current procurement system has several weaknesses such as sustainable financing, pharmaceutical strategic purchasing and consequently people's access to essential medicines. However, in line with the present research, studies show that type of financing, the payment system and the methods of purchasing medical services play important roles in the behavior of insured people and health care service providers.[2,15] In this regard, based on evidences in Social Security Organization, resources are exclusively funded from the premiums received by insured people and employers based on the percentage of salary. Since there is no governmental funding, the sources are more stable. Furthermore, the payment type at family physician level is based on per capita.[15] These strengths may provide an opportunity for the application of the mechanisms of resource allocation and strategic purchasing.

The results of this study indicate that facilitating the accessibility of essential medicines as one of the demand side interventions may be applied as a mechanism of resource procurement and allocation. In line with our findings, other studies suggest that applying family medicine and rural insurance programs, which 30% of their funding is allocated to the medicines procurement, has offered opportunity for providing urban and rural people with access to the essential medicines at the first level of referral system.[16] Moreover, other studies confirm the fact that, despite the current shortcomings, these programs have had acceptable performances in medicine management cycle, in the areas of selection, procurement and medicine distribution.[17] Furthermore, facilitating the access to relevant, effective and affordable drugs at the right time is of paramount significance. It is an indicator of health service utilization as well as the most visible determinant of quality and a major driving source of phenomenal increase in the longevity of the human productivity over the past decades. Thus according to the present finding and the results of the aforementioned studies, a substantial attention should be paid to this specific area.[18]

Providing insurance organizations with subsidies for specific diseases is another proposed mechanism related to the demand-side interventions obtained from the present findings. Public evidence shows that the success of subsidies schemes heavily depends on the existence of appropriate financing systems to compensate for the lost revenues from selling medicines.[19] Accordingly, it is suggested that the subsidy should be provided for the poor in the form of electronic cards.[5]

Encouraging the rational use of medicines as important mechanisms of demand-side intervention is considered to be an important factor in this study. Moreover, other studies show that all structures of RAP should consider the incorrect consumption of medicines in order to insure the optimal use of pharmaceuticals.[5,19] There exists another study indicating that the improper use of medicines in the public sector leads to excessive prescription, multiple medications, excessive use of antibiotics and unnecessary injections and a lower consumption of effective products.[20] In addition, the current study pointed out using training methods, correcting people's beliefs and enforcing rules and regulations as strategies for promoting rational medicine consumption. Similarly, another study mentioned that cultural factors, public education, and the media play less important roles in medicine utilization. On the other hand, parameters like social behavior, religious beliefs, social communication and physical activities had more significant roles in medicines utilization among the citizens.[21]

Concerning the supply-side interventions, the participants emphasized two factors; “defining a uniform pharmacopeia for all insurance companies” and “updating the uniform pharmacopeia according to local needs and essential medicine list.” In addition, evidence from other studies shows that matching the essential medicine list with the appropriate policy of medicine procurement is a tool to control costs and increase access to medicines, which is quite in line with the findings of the present study.[22]

Insofar as incentive policy is concerned, the interviewees believed that per capita can be employed as an incentive mechanism for implementing strategic purchasing of medicines. However, in Nepal, the mechanism of receiving consumer prices per each prescription instead of per each item has improved efficiency, reduced the number of items per patient and cut costs for each prescription.[23] Therefore, it is clear that these mechanisms should provide financial incentives to encourage rational prescriptions. Finally, according to the participants, mechanisms of price control through competition and regulation are considered as the most important motivational interventions. In this regard, other studies show that price is one important component of strategic purchasing of health care services, which is affected by payment method, the existence of related data, suppliers' and purchasers' characteristics, rules and regulations, negotiation power and the intensity of competition.[24]

In developing countries like Iran, it seems that shifting from pharmaceutical passive purchasing to a strategic one is the only option increasing access to essential medicines. Meanwhile, developed countries such as France have also set system to adjust medicines costs and ensure universal reimbursement of basic service package as the common goal in their pharmaceutical system reforms. In this regard, strategic purchasing of medicines has been considered as a lever affecting these reforms effectiveness.[25] Therefore, it seems that suggested interventions and mechanisms may help insurance organizations with moving toward a strategic purchasing in the pharmaceutical sector that includes the notion of increasing efficiency at health system level through stronger purchasing, which will ultimately lead to a better delivery in healthcare and better health outcomes.[26]

Allocating resources and purchasing arrangements along with enforcing rules and regulations can be considered as options in shifting from a passive purchasing to a strategic purchasing, increasing poor people's access to essential medicines and improving efficiency and equity in pharmaceutical system. It is obvious that these mechanisms provided within the World Bank model require localization and adjustment to conform to the local situation of any country. Therefore, it seems that the model presented in the study help to fulfill local needs and promote a higher accessibility of medicines through smart purchasing in developing countries like Iran.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was part of a PhD dissertation supported by Iran University of Medical Sciences grant No: 43/1392. Authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

AUTHORS' CONTRIBUTION

Dr. Peivand Bastani has designed the study, collected and analyzed the qualitative data and prepared the manuscript draft, Dr. Gholamhossein Mehralian has revised the manuscript technically and grammatically and finalized the article submitted, Dr. Rasoul Dinarvand has supervised the study.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mehralian G, Rangchian M, Javadi A, Peiravian F. Investigation on barriers to pharmaceutical care in community pharmacies: A structural equation model. Int J Clin Pharm. 2014;36:1087–94. doi: 10.1007/s11096-014-9998-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abachizade K, Bastani P, Abolhalaj M. A comprehensive analysis of drug system money map in Islamic Republic of Iran. J Econ Sustain Dev. 2013;4:158–64. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lu Y, Hernandez P, Abegunde D, Edejer T. Medicine Prices, Availability and affordability. 3rd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. The world medicine situation 2011; pp. 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Winkelmann R. Co-payments for prescription drugs and the demand for doctor visits - evidence from a natural experiment. Health Econ. 2004;13:1081–9. doi: 10.1002/hec.868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Preker AS, Langenbrunner JC. Spending Wisely Buying Health Services for the Poor. 1st ed. Washington DC: The World Bank Publisher; 2005. pp. 18–22. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abolhalaj M, Abachizade K, Bastani P, Ramezanian M, Tamizkar N. Production and consumption financial process of drugs in Iranian healthcare market. Dev Cty Stud. 2013;3:187–91. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Policy Making Council of Ministry of Health and Medical Education (Iran). Islamic Republic of Iran Health in the Fifth Economical, Social and Cultural Plan. The Institute, Tehran. 2009. [Last accessed on 2013 Aug 13]. pp. 21–7. Available from: http://www.behdasht.gov.ir/

- 8.Noori M. The Report of 5-years Performance of Iranian Social Treatment Security, Report of Iranian Health Sector Study, the Investigation of Secondary Information. 2008:8–16. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pouragha B, Pourreza A, Heydari H. Effect of access and out of pocket payment on GP's visit utilization: A data panel study among individuals covered by social security organization. Hakim Res J. 2011;15:101–11. [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2000: Health systems: Improving performance. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000. pp. 85–93. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferenz M, Nilsen K, Walters G. Research Methods in Management. 2nd ed. Canada: SAGE Publication; 2009. pp. 54–60. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jafari M, Rashidian A, Abolhasani F, Mohammad K, Yazdani S, Parkerton P, et al. Space or no space for managing public hospitals; a qualitative study of hospital autonomy in Iran. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2011;26:e121–137. doi: 10.1002/hpm.1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mehralian G, Rangchian M, Rasekh HR. Client priorities and satisfaction with community pharmacies: The situation in Tehran. Int J Clin Pharm. 2014;36:707–15. doi: 10.1007/s11096-014-9928-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mehralian GH, Yousefi N, Hashemian F. Knowledge, attitude and practice of pharmacists regarding dietary supplements: A community pharmacy-based survey in Tehran. Iran J Pharm Res. 2014;13:1455–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khakmardani AH. Determining a Model for Strategic Purchasing of Outpatient Health Care Services, World Health Organization, Final Report APW: 07/38. 2007:52–65. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenblatt RA, Andrilla CH, Curtin T, Hart LG. Shortages of medical personnel at community health centers: Implications for planned expansion. JAMA. 2006;295:1042–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.9.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Darbooy SH, Hoseini SA, Ahmadi B, editors. Pharmaceutical Management in Family Physician and Rural Insurance. Proceedings of the 1st National Congress of Management and Pharma Economics; 13-15 June, 2012; Tehran, Iran. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zarenezhad F, Mehralian GH, Rajabzadeh Ghatari A. Developing a model for agile pharmaceutical distribution: Evidence from Iran. J Basic Appl Sci Res. 2013;3:161–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levison L. Department of International Health, School of Public Health. Boston University; 2003. Policy and Programming Options for Reducing the Procurement Costs of Essential Medicines in Developing Countries [Concentration paper] pp. 75–82. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al Serouri AW, Balabanova D, Hibshi SA. Cost Sharing for Primary Health Care. Lessons from Yemen [working papers] Oxfam University; 2002. pp. 41–9. [Google Scholar]

- 21.GholiZadeh A, Vahid Dastjerdi AA, editors. Survey on Effective Cultural Elements on Drug Use. Proceedings of the 1st National Congress of Management and Pharma Economics; 13-15 June, 2012; Tehran, Iran. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quintal C, Mendes P. Underuse of generic medicines in Portugal: An empirical study on the perceptions and attitudes of patients and pharmacists. Health Policy. 2012;104:61–8. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holloway KA, Gautam BR, Reeves BC. The effects of different kinds of user fees on prescribing quality in rural Nepal. J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54:1065–71. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(01)00380-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Preker AS, Langenbrunner JC, Belli PC. Public Ends Private Means Strategic Purchasing of Health Services. 1st ed. Washington DC: The World Bank Publisher; 2007. pp. 11–25. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sermet C, Andrieu V, Godman B, Van Ganse E, Haycox A, Reynier JP. Ongoing pharmaceutical reforms in France: Implications for key stakeholder groups. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2010;8:7–24. doi: 10.1007/BF03256162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thomson S, Busse R, Crivelli L, van de Ven W, Van de Voorde C. Statutory health insurance competition in Europe: A four-country comparison. Health Policy. 2013;109:209–25. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2013.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]