Abstract

Sparganosis is caused by plerocercoid larvae of the Pseudophyllidea tapeworms of the genus Spirometra. Though prevalent in East Asian and south east Asian countries like China, Japan, Korea, Taiwan, Vietnam, Thailand; yet very few cases are reported from India. We report a case of migrating sub-conjunctival ocular sparganosis mimicking scleritis which later on developed into orbital cellulitis from Dibrugarh, Assam, North-eastern part of India. This case is reported for its rarity.

KEY WORDS: Spirometra, sparganum, Assam

INTRODUCTION

Sparganosis, a parasitic zoonosis was first described by Patrick Manson in 1882 caused by plerocercoid larvae of Pseudophyllidea tapeworms of the genus Spirometra.[1] Many species of Spirometra are recognized in clinical diseases that are Spirometra mansoni, Spirometra ranarum, Spirometra mansonoides, and Spirometra erinacei. The species identification can only be done after feeding them to natural definitive hosts like dogs and cats where it develops into adult worms.[2] Humans are accidental intermediate hosts and worms develop into plerocercoid larvae that migrate into the tissue and cause local inflammation at the final sites.[3] It is most frequently found in eastern and south eastern Asia mainly from countries like Japan, China, Korea, Taiwan, Vietnam, Thailand.[4] There are two types of the disease, namely nonproliferative and proliferative sparganosis. Though about 450 cases of human sparganosis have been reported worldwide, these infections are rarely reported from India.[5,6,7,8,9,10] We report a case of sub-conjunctival ocular sparganosis mimicking scleritis initially developing into orbital cellulitis and later on presenting as a migrating subconjunctival cyst.

CASE REPORT

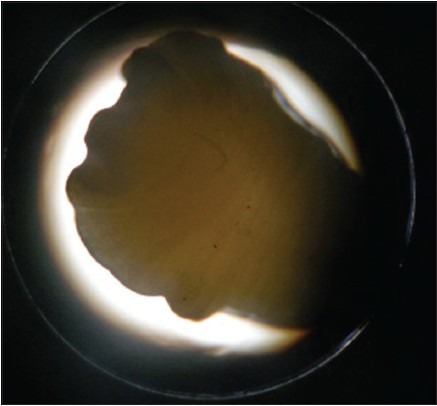

A 32-year-old male presented with a painful subconjunctival horseshoe shaped swelling around the limbus in the superior part of the bulbar conjunctiva with surrounding chemosis and congestion [Figure 1]. Other ocular examination findings of both the eyes were within normal limits including fundi and visual acuity. The swelling initially started in the lower part of the eye, in the infero-lateral part of the bulbar conjunctiva 2½ years back; for which he went to a private eye hospital. Computed tomography scan report at that time was suggestive of orbital pseudotumor. Blood examination findings including blood sugar and cell count were within normal limits. The patient was treated with topical as well as oral corticosteroid (60 mg daily, which was tapered off within a period of 6 weeks). But the lesion did not resolve; for which he consulted several ophthalmologists. As the patient did not get relief, he started taking oral prednisolone 10 mg on his own whenever symptoms like pain, redness and swelling aggravated. This went on for 26 months after which he developed pain, swelling and redness in his left leg in October 2011. He consulted a physician and was diagnosed with steroid induced type 2 diabetes mellitus with cellulitis of the left leg. At the time of diagnosis, his postprandial blood sugar was 378 mg%, and fasting blood sugar was 153 mg %. He was hospitalized for 10 days and treated with metformin at a dose of 500 mg twice daily and injectable piperacillin and tazobactam. After treatment, his blood sugar came down to normal limit and cellulitis resolved. During this time, the nodular mass in the superior bulbar conjunctiva decreased in size to 3 cm × 2.5 cm and appeared fixed to sclera [Figure 2]. Ultra-sonography of the eye showed a hazy mass without any fluid in the episcleral area with no intra-ocular extension [Figure 3]. The patient was advised surgical excision, but he refused surgery. After 6 weeks, he again reported with increased pain and swelling. On examination, the lesion was found to be covering almost the whole of the upper part of the limbus as in Figure 1. Patient agreed for surgical excision this time and on opening the cystic wall a little fluid came out with a white ribbon like worm (cestode larvae) with a yellow coiled area around the broadened head [Figure 4]. The cyst was removed and sent for histopathological examination, and the worm was sent to Department of Microbiology for identification in formalin. The patient was given moxifloxacin 0.5% eye drop 8 hourly for 4 weeks and prednisolone acetate 1% eye drop initially 2 hourly for 7 days and then tapered as 4 hourly for 7 days, 6 hourly for 7 days and 8 hourly for 7 days. Tablet ciprofloxacin 500 mg 12 hourly and tablet ibuprofen and paracetamol were given orally both for 5 days. The inflammation and other symptoms resolved after 2 days, and he was discharged from hospital. The patient was lost to follow-up after his discharge from hospital.

Figure 1.

Swelling around the upper part of the limbus

Figure 2.

Nodular mass at 12 O'clock position in superior bulbar conjunctiva

Figure 3.

Ultrasonography of the orbit showing the cyst in the superior part

Figure 4.

White ribbon like worm with a yellow coiled area around the broadened head

The worm was a cestode larva, about 40 mm × 1 mm in size, flat with a broadened anterior end which appeared as pseudoscolex, without any mature proglottids and showed presence of bothria [Figures 5–7]. There were no suckers. The larva was identified as sparganum, the plerocercoid larvae of the genus Spirometra.

Figure 5.

Anterior end of the worm

Figure 7.

Body of the worm

Figure 6.

Posterior end of the worm

CONCLUSIONS

Adult Spirometra lives in the intestines of dogs and cats. Eggs are released into fresh water and hatch into the coracidia, which are ingested by copepod crustaceans. Coracidia develop into procercoid larvae in the copepod; primary, intermediate host. Infected copepods are ingested by secondary intermediate hosts including reptiles, amphibians, fish, and procercoid develops into plerocercoid. The plerocercoid develops to mature worms in definitive hosts, dogs, and cats. Humans are accidental intermediate or paratenic hosts for Spirometra worms where the procercoid or plerocercoid larvae migrate and move around in tissues till they settle. Human get infected by drinking untreated water containing infected copepods, ingesting raw or inadequately cooked second intermediate hosts, e.g. flesh of snakes or frogs infected with the plerocercoid larvae and by applying the flesh of an infected intermediate host as a poultice on the open wounds, eyes or other lesions for medicinal or ritualistic reasons.[4,11,12] Once ingested or directly entered into the lesion, the sparganum directly and painlessly can invade intestinal wall, move under the peritoneum and migrate into various tissues; may invade muscles, subcutaneous tissue, urogenital and abdominal viscera, and sometimes, the central nervous system and the eyes.[13] Spargana usually infect subconjunctival and conjunctival tissues causing symptoms varying from simple itching due to the local granuloma and more serious signs as local pain, epiphora, chemosis, and ptosis.[14,15] Conjunctival infection may also be characterized by irritation, continued foreign body sensation, redness and mimic signs and symptoms of orbital cellulitis, with exophthalmia and corneal ulcers.[8] When the immature cestode invades the orbit, it may cause acute anterior uveitis and iridocyclitis and severe inflammation with blindness.[5,16] We summarized the cases reported from India in Table 1. Surgery is the only effective treatment. Our patient developed infection of the subconjunctival tissue in the infero-lateral aspect of the bulbar conjunctiva initially which migrated to the superior part. The lesion appeared as scleritis initially which later on presented as orbital cellulitis and perilimbal cyst. It caused diagnostic dilemma and refusal of surgery by the patient caused delay in treatment and diagnosis. The worm was excised out after 2 years and 8 months of initial presentation. Our patient gave a history of drinking treated water at his home; though occasionally he gives a history of taking untreated water in his work place. Probable route of entry in our patient is drinking untreated water though occasionally. Other food history was unremarkable. The determination of sparganum species must be made from the adult form. S. erinacei metacestode is the frequently recovered sparganum in the Orient.[4] Accurate species identification requires feeding the sparganum to a proper definitive host. That is, a dog or cat and recovering the adult parasite for further morphologic study, However, species identification could not be made in our case.

Table 1.

The cases of human sparganosis reported from India

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Authors acknowledge the help of Parasitology Division, Center for Disease Control, Atlanta, USA in the preliminary identification of the worm.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beaver PC, Jung RC, Cupp EW. Clinical Parasitology. 9th ed. Philadelphia: Lea and Febiger; 1984. pp. 499–504. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wittner M, Tanowitz HB. Other cestode infections. In: Guerrant RL, Walker DH, Weller PF, editors. Tropical Infectious Disease. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 1999. pp. 1928–9. [Google Scholar]

- 3.King CH. Cestodes (tapeworms) In: Mandell GL, Bennette JE, Dolin R, editors. Mandell, Douglas and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2005. p. 3292. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ausayakhun S, Siriprasert V, Morakote N, Taweesap K. Ocular sparganosis in Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1993;24:603–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sen DK, Muller R, Gupta VP, Chilana JS. Cestode larva (sparganum) in the anterior chamber of the eye. Trop Geogr Med. 1989;41:270–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kudesia S, Indira DB, Sarala D, Vani S, Yasha TC, Jayakumar PN, et al. Sparganosis of brain and spinal cord: Unusual tapeworm infestation (report of two cases) Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1998;100:148–52. doi: 10.1016/s0303-8467(98)00027-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sundaram C, Prasad VS, Reddy JJ. Cerebral sparganosis. J Assoc Physicians India. 2003;51:1107–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Subudhi BN, Dash S, Chakrabarty D, Mishra DP, Senapati U. Ocular sparganosis. J Indian Med Assoc. 2006;104:529–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mukherjee B, Biswas J, Raman M. Subconjunctival larva migrans caused by sparganum. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2007;55:242–3. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.31959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duggal S, Mahajan RK, Duggal N, Hans C. Case of sparganosis: A diagnostic dilemma. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2011;29:183–6. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.81789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qiu MH, Qiu MD. Human plerocercoidosis and sparganosis: II. A historical review on pathology, clinics, epidemiology and control. Zhongguo Ji Sheng Chong Xue Yu Ji Sheng Chong Bing Za Zhi. 2009;27:251–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li MW, Lin HY, Xie WT, Gao MJ, Huang ZW, Wu JP, et al. Enzootic sparganosis in Guangdong, People's Republic of China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1317–8. doi: 10.3201/eid1508.090099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ou Q, Li SJ, Cheng XJ. Cerebral sparganosis: A case report. Biosci Trends. 2010;4:145–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yang JW, Lee JH, Kang MS. A case of oular sparganosis in Korea. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2007;21:48–50. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2007.21.1.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kittiponghansa S, Tesana S, Ritch R. Ocular sparganosis: A cause of subconjunctival tumor and deafness. Trop Med Parasitol. 1988;39:247–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rehák M, Kolárová L, Kohnová I, Rehák J, Mohlerová S, Fric E, et al. Ocular sparganosis in the Czech Republic - A case report. Klin Mikrobiol Infekc Lek. 2006;12:161–4, 155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]