Abstract

From the point of view of deontological ethics, privacy is a moral right that patients are entitled to and it is bound to professional confidentiality. Otherwise, the information given by patients to health professionals would not be reliable and a trustable relationship could not be established. The aim of the present study was to assess, by means of questionnaires with open and closed questions, the awareness and attitudes of 100 dentists working in the city of Andradina, São Paulo State, Brazil, with respect to professional confidentiality in dental practice. Most dentists (91.43%) reported to have instructed their assistants on professional confidentiality. However, 44.29% of the interviewees showed to act contradictorily as reported talking about the clinical cases of their patients to their friends or spouses. The great majority of professionals (98.57%) believed that it is important to have classes on Ethics and Bioethics during graduation and, when asked about their knowledge of the penalties imposed for breach of professional confidentiality, only 48.57% of them declared to be aware of it. Only 28.57% of the interviewees affirmed to have exclusive access to the files; 67.14% reported that that files were also accessed by their secretary; 1.43% answered that their spouses also had access, and 2.86% did not answer. From the results of the present survey, it could be observed that, although dentists affirmed to be aware of professional confidentiality, their attitudes did not adhere to ethical and legal requirements. This stand of health professionals has contributed to violate professional ethics and the law itself, bringing problems both to the professional and to the patient.

Keywords: Ethics, Bioethics, Dentistry, Behavior, Attitude

INTRODUCTION

In view of the moral dimension of man's behavior, the classes of Ethics and Bioethics, usually presented as critical reflections on morality, are feared by most health professionals and students, probably due to their lack of knowledge of this subject. Thus, it is the duty of academic courses in the health field filed to turn it possible for undergraduates to have contact with ethical values in a clear, deep and unabridged manner, in order to make them question these, values and search for consistency27.

The requirements of a strict Code of Ethics, which is not at the service of professional privileges, but that is rather constituted of duties and bound to social ethics, is of paramount importance, so that the interests of the public may be protected 4. In this ethical context, privacy is a principle derived from autonomy and covers people's intimacy, honor and image. It is assumed that, in order to guarantee someone's privacy, the confidentiality of all information referring to this person must be preserved, it is the health professional's duty to protect it11,20.

In Brazil, dentistry is considered as an autonomous profession, which means that dental education is independent from medical education, Thus, dentists, except for oral and maxillofacial surgeons, usually do not have contact with hospital staff.

In the health field, particularly in dentistry, privacy is directly associated with professional confidentiality, a special type of secrecy in which the confidant is the member of a certain profession and all disclosed information must be kept confidential. It may also be interpreted as promised secrecy because the professional, in the oath taken in the graduation ceremony, swears to protect patient's privacy24,27.

Although it is of great importance to keep professional confidentiality18, it is observed that few Brazilian schools in the health field have classes on Ethics and Bioethics in their undergraduate curriculum. This incoherence reveals that the future professionals are unprepared with respect to ethics and legislation, which are the classes that intend to improve dental students' knowledge of the complex professional/patient/family relationship.

The Code of Ethics of Dentists, in its 4th article, clause XI, informs that health professionals should "keep professional confidentiality". However, in its 1st paragraph, it presents situations in which confidentiality may be breached, such as in the case of compulsory notification of diseases; cooperation with justice in the cases provided by law; forensic dental examination within its limits; strict defense of legitimate interest of the professional; and disclosure of confidential fact to the guardian of a legally incapacitated individual4.

The preservation of health professional confidentiality relies on the fact that any professional, either doctor, nurse or dentist, as well as technical assistants, get to know confidential facts and are, by the force of law and ethical codes, obligated to maintain these facts in secrecy4,12. Although the exchange of information is necessary in an interdisciplinary health team, each professional should limit information disclosure to what is really deemed necessary to plan and accomplish the procedures in the patient's best interest 2,21. For health professionals, confidentiality comprises all information to which they have access by clinical interview, physical examination, patient care, lab or radiological results, or clinical conference witrh other professionals involved in the treatment13,17. The commitment to keep confidentiality is the guarantee the patient needs to overcome the embarrassment of answering the questions asked during the clinical interview9,26.

Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to evaluate the knowledge and attitudes of 100 dentists in the city of Andradina, São Paulo State, with regard to professional confidentiality in dental practice.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

The research protocol was first submitted to review by the Ethics in Research Committee of the School of Dentistry of Araçatuba, UNESP, and the study design was approved (protocol number 67/2004).

This descriptive and transversal (or cross-sectional) survey aimed to identify and analyze the knowledge and attitudes of 100 dentists registered at the Regional Dental Council of São Paulo State (CRO/SP), section of the city of Andradina, who live and work in that municipality, with regards to professional confidentiality. All dentists registered at CRO/SP (n=120) were invited to participate, but only 100 agreed to take part in the study. After being introduced to the goals of the survey, the professionals who agreed to participate signed an informed consent form.

A semi-structured, self-applied questionnaire arguing about the dentists' knowledge and attitudes concerning professional confidentiality was used as an analytical tool. The analyzed variables included the kind of guidance given by the dentists to their auxiliary staff, who had access to dental records, their knowledge of the Code of Ethics regarding professional confidentiality, among others. The strategy for data collection consisted of visits to dental offices and clinics. A pilot study with 20 professionals not belonging to the study population was first performed to refine the questionnaire.

The collected data were tabulated and analyzed statistically using absolute and relative frequencies. Data were entered into Epi-info 2000 (version 6.04; Atlanta, Georgia, USA)6, and presented graphically for better visualization and discussion of the results.

RESULTS

The age of the interviewees ranged from 23 to 64 years (mean age = 35.16 years). Seventy-four percent (n=69) of them were male and 26% (n=31) were female. The interviewees had been graduated for 12.19 years on average, ranging from 1 year to 42 years of clinical practice. 58.57% of the participants had graduated from private dental schools. Statistically significant differences were observed between the professionals graduated from public (average of 9.25 years) and private (average of 15 years) dental schools (p= 0.0187).

Student's t-test was also performed to verify the differences between male and female dentists concerning the variables age and time of clinical practice. Female and male mean age was 33 years (±8) and 37 years (±11), respectively. Female and male mean time of clinical practice was 12.9 years (±11.9) and, 12.33 years (±9.92). However, there was no statistically significant difference between the variables, with p=0.0888 (gender and age) and p=0.4648 (gender and time of clinical practice).

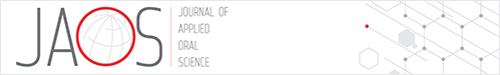

Most interviewees (91.43%) reported to instruct their assistants with regard to professional confidentiality and, from this total, 57.81% did it orally. In spite of that, 44.29% of the repondents affirmed to make comments about their patients' clinical cases with friends or spouses, thus denoting breach of professional confidentiality (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. Percent distribution of dentists according to breach of professional confidentiality to friends or spouses. Andradina/SP, 2006.

To verify the differences existing concerning age and time of clinical practice, logistic regression by Wald chi-square test was carried out with all possible variables in the questionnaire. Only the information related to talking to friends or spouses about clinical cases and type of dental school (public or private) presented statistically significant differences with p=0.0217 for age and p=0.0187 time of clinical practice.

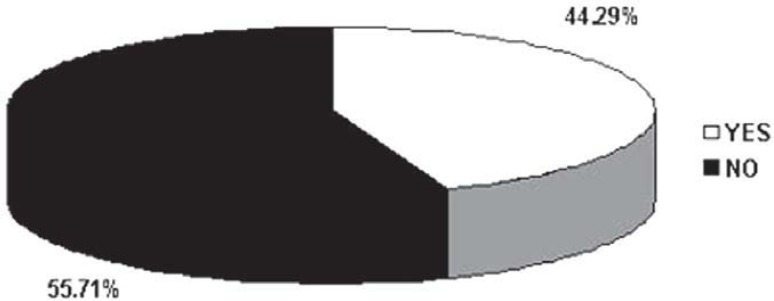

A total of 28.57% of the dentists answered to have exclusive access to patients' information, 67.14% shared access with their assistant, 1.43% of them affirmed to share access to patient information with their spouses, and 2.86% did not answer (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2. Percent distribution of the people with access to the dental records of the patients treated by the interviewed dentists Andradina/SP, 2006.

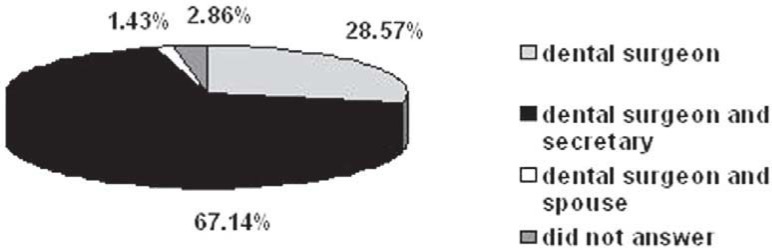

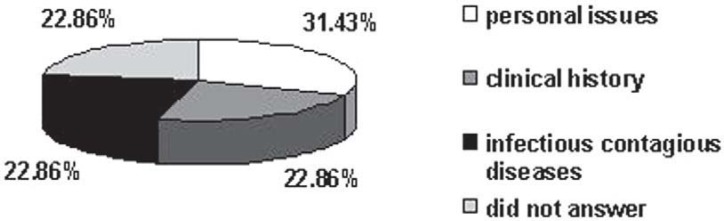

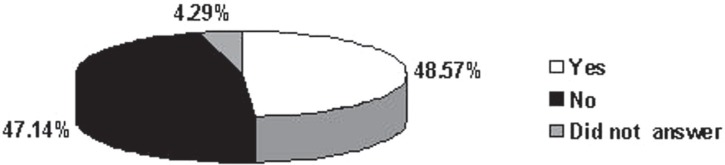

Concerning the knowledge of the ethical concepts issued in the Code of Ethics, most interviewees (88%) affirmed to be aware of the ethical aspects related to professional confidentiality. However, when questioned about what would characterize a "breach of professional confidentiality", there was a disparity because 22.86% of the interviewees considered that it would be the disclosure of facts of the patient's clinical history; 31.43% mentioned disclosure of personal issues; 22.86% answered compulsory report of infectious-contagious diseases; and 22.86% did not answer (Figure 3). Among all interviewees, 48.57% affirmed to be aware of the penalties imposed in case of damage to a patient due to breach of confidentiality (Figure 4).

FIGURE 3. Percent distribution of the dentists according to the type of information they consider breach of confidentiality. Andradina/SP, 2006.

FIGURE 4. Percent distribution of the dentists according to awareness of the penalties imposed in case of breach of confidentiality Andradina/SP, 2006.

Almost all participants (98%) agreed with respect to the need for classes on Dental Ethics and Bioethics during the undergraduate course.

DISCUSSION

In the activities of health care, professional confidentiality originates from Hippocrates, who affirmed: "Whatever, in connection with my professional practice, or not in connection with it, I see or hear, in the life of men, which ought not to be spoken of abroad, I will not divulge, as reckoning that all such should be kept secret"14. In view of that, most interviewees (91.43%) informed that they oriented their auxiliary personnel about professional confidentiality; 52.86% did it orally, 2.86% in a didactical way and 35.71% did not want to reveal how they used to instruct their staff. This suggests that the absence of orientation of dental assistants about professional confidentiality occurs due to negligence or lack of knowledge of the importance to do so. Masic and Ridandvic16 (1995) emphasized that all categories of dental professionals are responsible for confidentiality, which includes dental assistants, who may have access to the information when handling files of clinical documents. In case of confidentiality breach, the dentist may be considered lenient, if he/she had neglected orientation towards this subject.

Renson23, (1994) and Maccon15, (2005) affirm that some situations, such as disclosure of the existence of infectious-contagious disease or information considered essential to continue the patient's dental treatment, cannot be considered breach of confidentiality. The disclosure of these facts is a way of avoiding that health professionals are exposed to numerous problems. The law provides for exceptions in the keeping of confidentiality when the professional's health is at stake (Dimond7, 2006 and Nicol19, 1997).

Sirinskiene, et al.25. (2005) explored the limits of confidentiality in the context of HIV-positive patients. They assume that, in this case, confidentiality may be breached to inform the patient's spouse, caregiver or health professional in charge. Nevertheless, before being shared with patient, the strictly confidential information has to be analyzed, taking into consideration the patient's autonomy, psychological and mental state.

Ponte22, (2006) emphasized that even when an interdisciplinary team is working together, there is no need for all members to have all information about the patient. Dentists and dental assistants should share patient information provided this sharing is not limited, only when this disclosure is in the patient's best interest.

Although 91.43% of the dentists declared to orient their assistants with regards to professional confidentiality, it was verified that they themselves did not keep it, as 44.29% of them affirmed to talk about the clinical cases of their patients to friends or spouses.

Regarding the responsibility about patient information, it was verified that 28.57% of the professionals had exclusive access to the clinical files, 67.14% affirmed to share the access with their assistants, 1.43% with the spouse, and 2.86% did not answer. Castledine5, (2006) affirms that it is very important to keep the privacy of the patients' dental records to ensure confidentiality of the information.

The present survey on ethical principles allowed concluding that, although 88% of the interviewees affirmed to be aware of the aspects related to professional confidentiality, they disagreed with respect to what was deemed breach of confidentiality, as 31.43% mentioned the disclosure of issues related to personal life, 22.86% disclosure of clinical history, 22.86% disclosure of information about infectious-contagious diseases, and 22.85% did not answer.

Hariharan, et al.10, (2006) reported, in a recent study, that some health professionals, doctors and nurses also presented a poor understanding of the ethical and legal principles and concepts of professional confidentiality. Having detected the problem, the authors concluded that it is necessary to reinforce the study of ethical and legal texts to prepare health professionals to deal with the problems of their daily routine.

With regards to the professional's awareness of the penalties imposed in case of breach of professional confidentiality, 48.57% declared to be aware of them, 47.14% affirmed to be unaware and 4.29% did not answer. It was observed that teaching Ethics and Bioethics is of key importance, as it contributes to increase undergraduates' understanding about the complex professional-patient-family relationship and be aware that professional confidentiality is mandatory for exercising a profession in the health field14.

The Brazilian Curricular Guidelines for the Dental Course were issued by the Resolution CNE/CES 4 (February 19, 2001). These Guidelines strengthen the relevance of Bioethics and Ethic disciplines on curricular structure because these disciplines introduce health professionals-to-be to the rights and duties of their profession3. The great majority of the interviewees (98%) affirmed that the classes of Ethics and Bioethics were of great importance in the curriculum of undergraduates.

Graham8, (2006) affirms that keeping professional confidentiality is one of the key ethical concepts. Thus, it should be given priority in medical education. The best way to do this is to introduce these concepts in the curriculum of all health courses so that undergraduates might understand their ethical, professional and legal duties still during graduation years and put them in practice while exercising professional careers. This approach might consolidated the knowledge of the future dentists and, eventually, influence their relationship with patients. Currently, this fact should not be neglected, as patient/professional relationship is no longer thoroughly based on confidence. In the past, the blind confidence in health professionals hindered a better understanding of treatment and cure of diseases by the patients. In present days, there is no doubt about the patients' awareness and ability to understand the contractual nature of the relationship that binds them to the professionals1.

The introduction of the disciplines of Ethics and Bioethics in the curriculum of all health graduate courses would be a valuable approach to improve the current scenario. This would allow students having contact with ethical and legal issues that might arise in their clinical practice, such as those related to patients' privacy and professional confidentiality. Furthermore, they would be better informed on how to behave in face of those issues. This change in dental education would also bring about a better ethical conduct in the clinical practice, as dentists would understand the dispositions of the Code of Ethics and comply with than without fearing the penalties imposed for infractions.

CONCLUSIONS

The following conclusions may be drawn: 1. Although the interviewed dentists (living and working in the city of Andradina, São Paulo State, Brazil) reported to be aware of professional confidentiality, they showed indifference towards dental ethical and legal aspects; 2. Breach of professional confidentiality was evident since the participants revealed to disclose information regarding clinical cases to assistants, friends and spouses; 3. Professional confidentiality must be protected in all fields in order to maintain a harmonious relationship among patients, families and dentists; 4. The results of the present survey illustrate the reality of a city located in the northwest of São Paulo State; it does not represent the reality of the entire State or Brazil. further research should be conducted in order regions in order to confirm or confront these findings.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank FAPESP for financial support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beech M. Confidentiality in health care: conflicting legal and ethical issues. Nurs Stand. 2007;21(21):42–46. doi: 10.7748/ns2007.01.21.21.42.c4513. 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bennetti M E, Weyant R J, Simon M. Predictus of dental studente's belief in the rights to refese treatmente to HIV-positive patients. J Dent Educ. 1993;57(9):673–678. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brasil. Ministério da Educação. Resolução CNE/CES n° 3. Conselho Nacional da Educação/Conselho de Educação Superior. 2002. publicado no dia 19 de fevereiro de.

- 4.Brasil. Conselho Federal de Odontologia. Prontuário Odontológico. Rio de Janeiro: Conselho Federal de Odontologia; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Castledine G. The importance of keeping patient records secure and confidential. Br J Nurs. 2006;15(8):466–466. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2006.15.8.20968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dean AG, Dean JA, Burton AH, Dicker RC. Epi Info, Version 6: a word processing, database and statistics program for epidemiology on micro-computers. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta, Georgia, USA: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dimond B. Legal aspects of continence: disclosure of a medical condition. Br J Nurs. 2006;15(8):467–468. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2006.15.8.20969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graham HJ. Patient confidentiality: implications for teaching in undergraduate medical education. Clin Anat. 2006;19(5):448–455. doi: 10.1002/ca.20345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gupta S, Bhardwaj DN, Dogra TD. Confidential communications in medical care. Indian J Med Sci. 1999;5(10):429–433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hariharan S, Jonnalagadda R, Walrond E, Moseley H. Knowledge, attitudes and practice of healthcare ethics and law among doctors and nurses in Barbados. BMC Medical Ethics. 2006;7(1):7–7. doi: 10.1186/1472-6939-7-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heikkinen AM, Wickström GJ, Leino-Kilpi H. Privacy in occupational health practice: promoting and impeding factors. Scand J Public Health. 2007;35(2):116–124. doi: 10.1080/14034940600975740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hough G. When confidentiality mandates a secret be Kept: a case report. Int J Group Psychother. 1992;42(1):105–115. doi: 10.1080/00207284.1992.11732582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kihlgren M, Thorsen H. Violation of the patient's integrity, seen by staff in long-term care. Scand J Caring Sci. 1996;10(2):103–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.1996.tb00319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Louvrier P. Professional confidentiality and the family. Rev Med Brux. 2006;27(4):396–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maccoon K. To what extent should a colleague be unnecessarily exposed to risks for the sake of protecting patient privacy: an ethical dilemma. Health Law Can. 2005;26(2):13–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Masic I, Ridanovic Z. Ethical principles in health data protection. Med Arh. 1995;49(1-2):41–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mole DJ, Fox C, Napolitano G. Electronic patient data confidentiality practices among surgical trainees: questionnaire study. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2006;88(6):550–553. doi: 10.1308/003588406X117089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nichols PS, Winslow GR. How strict is confidence? Gen Dent. 2004;52(1):15–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nicol TE. Confidentiality versus disclosure of a patient's infectious status. Gen Dent. 1997;45(1):78–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O'Neil MK. Confidentiality, privacy, and the facilitating role of psychoanalytic organizations. Int J Psychoanal. 2007;88:691–711. doi: 10.1516/0334-5427-247w-x038. Pt 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Phaosavasdi S, Thaneepanichskul S, Tannirandorn Y, Pupong V, Uerpairojkit B, Pruksapongs C, Kajanapitak A. The idealistic ethical doctor. J Med Assoc Thai. 2007;90(1):201–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ponte C. Confidentiality and professional secrecy in health establishments. Soins. 2006;(710):22–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Renson CE. Ethical dilemmas in dentistry. Dent Update. 1994;21(6):225–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simonsen S, Nylenna M. Basic ethical, professional and legal principles of biomedical research. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2006;(Suppl 2):5–14. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sirinskiene A, Juskevicius J, Naberkovas A. Confidentiality and duty to warn the third parties in HIV/AIDS context. Med Etika Bioet. 2005;12(1):2–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sote EO. AIDS and infection control: experiences, attitudes, knowledge and perception of ocupacional hazards among Nigerian dentists. Afr Dent J. 1992;(6):1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zabala-Blanco J, Alconero-Camarero AR, Casaus-Pérez M, Gutiérrez-Torre E, Saiz-Fernández G. Evaluation of bioethical aspects in health professionals. Enferm Clin. 2007;17(2):56–62. doi: 10.1016/s1130-8621(07)71770-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]