Summary

Background:

frozen shoulder is a common condition and its management can be surgical or non-surgical. The aim was to determine current trends in the management of frozen shoulder amongst surgical members of the British Elbow and Shoulder Society (BESS).

Methods:

a single electronic questionnaire was emailed to surgical members of the BESS. Participants were asked about their surgical and non-surgical treatments of choice and the reasoning behind that, as well as which components of arthroscopic arthrolysis they favoured.

Results:

87 BESS members completed the questioner. The majority of respondents used physiotherapy as their preferred means of non-surgical management while arthroscopic arthrolysis was the most frequently used surgical intervention. A substantial proportion of surgeons based their choice on personal experience and training rather than published evidence.

Conclusions:

management of frozen shoulder amongst surgeons varies substantially and is highly based on personal experience and training rather than strong evidence. Arthroscopic arthrolysis is a heterogeneous procedure with a wide variation in the use of its various components. Our results highlight the need for high quality clinical trials to compare the management options available.

Keywords: adhesive capsulitis, arthroscopic arthrolysis, frozen shoulder, shoulder surgery

Introduction

Frozen shoulder is a common condition with a prevalence of up to 8.2% of men and 10.1% of women of working age1. It can be either primary or secondary to another cause such as diabetes. It is classically described in 3 phases; phase 1, where pain predominates, phase 2 where stiffness predominates and phase 3, where symptoms begin to resolve2. The natural history of frozen shoulder is such that spontaneous improvement in symptoms occurs in most and thus treatment aims at alleviating current symptoms and speed up recovery3–6. Management of frozen shoulder can be surgical or non-surgical. Non-surgical treatment may be in the form of watchful waiting or supervised neglect, oral analgesia and anti-inflammatory drugs, physiotherapy (capsular stretching), glenohumeral steroid injections or joint distension4,5,7–12. Surgical treatment may be in the form of manipulation under anaesthesia (MUA), which involves passively moving the arm to tear the thickened inflamed coraco-humeral and glenohumeral ligaments as well as stretch the capsule, or arthroscopic arthrolysis, which allows direct division of the involved ligaments and capsular release. Open capsular release allows release of the thickened ligaments and capsule using an open incision rather than an arthroscopic approach4, 11–21. Non-surgical means are usually the first line of choice followed by surgical intervention in those who fail to respond. There is limited evidence to support one non-surgical treatment over the other or one type of surgery over another type of surgery22, 23. With the wide variety of interventions available, high quality clinical studies that will explore these issues are of paramount importance.

Understanding current trends in the management of frozen shoulder is an important first step in the design of comparative trials. The aim of this study is to determine the current trends in the management of frozen shoulder amongst surgical members of the British Elbow and Shoulder Society (BESS).

Methods

The survey was undertaken by emailing a single electronic questionnaire to 472 surgical members of the BESS. The questionnaire was designed using the Survey Monkey internet tool, a link to which was embedded in the invitation email. Our study was conducted in accordance with international ethical standards for this type of research24.

The questions enquired about the demographics of the participants, the types of non-surgical and surgical treatments they utilise, the basis for choosing their preferred treatment, whether their approach to surgical and non-surgical management was influenced by any factors such as underlying cause or chronicity. The questionnaire also enquired about the number of surgical procedures that the participants performed in a given year. For those performing arthroscopic arthrolysis the various components of the surgical technique employed were also investigated. The questionnaire was first emailed in August 2012 and was left open for a total of 14 weeks after which no further responses were analysed. Answers given under the option “other” were analysed and where possible, applied to the options listed above.

Results

88 respondents completed the questionnaire (87 fully, 1 partially). The experience of the participants ranged from 1 to 28 years as a shoulder surgeon with a median of 10 years. When asked how many frozen shoulders they managed annually a range of 1.5 (3 in 2 years) to 200 was generated with a median of 45.

The distribution of non-surgical treatment modalities amongst respondents is shown in Table 1. The basis for making a decision on which non-surgical treatment to use came predominantly from a combination of personal experience/training and published clinical evidence (Tab. 1). The distribution of surgical treatment modalities amongst respondents is shown in Table 2. The basis for making a decision about the type of surgery, came mostly from a mixture of personal experience/training and published clinical evidence but in a large proportion this came simply from personal experience (42.5%).

Table 1.

The most common pre-surgical treatments used for the stiffness predominant phase of frozen shoulder and the reasoning behind the given choice.

| Pre-Surgical Treatments for the Stiffness Predominant Phase | |

|---|---|

| Answer Options | Count (%*) |

| None | 13 (14.9) |

| Physiotherapy | 59 (67.8) |

| Steroid Injection | 47 (54) |

| Capsular Distension | 34 (39) |

| Other (see below) | 8 |

|

| |

| Steroid injection for the painful phase (3); if chronic (>6 months), straight to surgery; allow activity of daily living in comfort zone; patient preference; supervised neglect in the majority of cases; steroid injection only for early stage.

| |

| Rational for the Above | Count (%) |

|

| |

| Personal Experience/Training | 23 (26.4) |

| Published Evidence | 4 (4.6) |

| Both | 53 (61) |

| None | 7 (8) |

| Total | 87 |

| Other (see below) | 6 |

Patient preference (3); duration and severity; audit of personal results; safest treatments first.

Percentage calculated form the total number of participants who answered the question (87) as they were allowed to choose more than one answer.

Table 2.

The most common surgical treatments used for the stiffness predominant phase of frozen shoulder and the reasoning behind the given choice.

| Surgical Treatments for Stiffness Predominant Phase | |

|---|---|

| Answer Options | Count (%*) |

| None | 6 (6.9) |

| Manipulation Under Anaesthesia | 41 (47) |

| Arthroscopic Arthrolysis | 77 (88.5) |

| Open release | 2 (2.3) |

| Other (see below) | 6 |

|

| |

| Above are combined (2); hydro-dilation; Capsular Release has fewer recurrences than MUA; MUA for primary FS, capsular release for failed MUA and FS secondary to operative intervention (excluding Arthroscopic Subacromial Decompression) or trauma; In severe stiffness, arthroscopic release and block.

| |

| Rational for the Above | Count (%) |

|

| |

| Personal Experience/Training | 37 (42.5) |

| Published Evidence | 3 (3.4) |

| Both | 43 (49.4) |

| None | 4 (4.6) |

| Total | 87 |

| Other (see below) | 6 |

Response to conservative management (4); severity of symptoms; patient requirements and comorbidities.

Percentage calculated from the total number of participants who answered the question (87) as they were allowed to choose more than one answer, MUA Manipulation Under Anaesthesia.

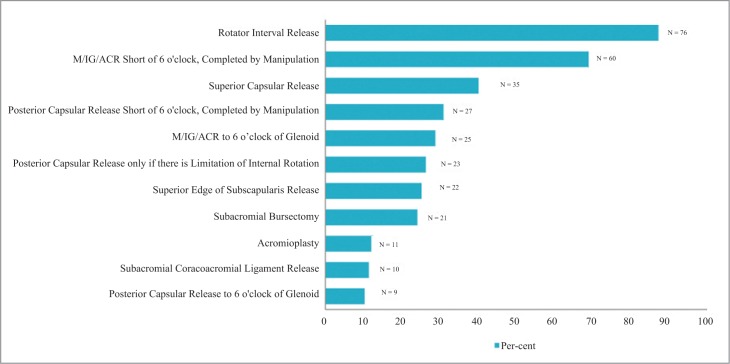

Of the 87 respondents who answered the questionnaire, 55.17% indicated that their approach to operative and non-operative management of the stiffness predominate phase was influenced by the underlying cause of frozen shoulder, chronicity or other factors, while 44.83% indicated it did not. Those who did take this into consideration indicated that factors influencing the type of treatment included a history of diabetes (20), chronicity of symptoms (9), degree of stiffness (9), failure of conservative management (9), functional loss (8), patient choice (7), underlying cause of FS (4), recurrence (3), and bilateral involvement (2) as shown in Table 3. Arthroscopic arthrolysis was a very heterogeneous surgical procedure with great variations amongst respondents as to which of its components they perform (Fig. 1).

Table 3.

Factors influencing the approach to operative and non-operative management for the stiffness predominant phase of frozen shoulder.

| Issue | Respondents | Expanded Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Diabetes | 20 | Surgery more likely/earlier (11); More aggressive approach (4); Arthroscopic arthrolysis more likely (3) |

| Chronicity | 9 | Surgery more likely/earlier (5) |

| Degree of stiffness | 9 | Arthroscopic release in severe stiffness (4); Other response: MUA is first choice for severe stiffness; poor results with hydro-dilatation in severe stiffness; MUA plus steroid injection in severe early phase stiffness. |

| Conservative management failure | 9 | Surgery more likely/earlier |

| Functional loss | 8 | Surgery more likely/earlier (4) |

| Patient led decision process | 7 | Discussion of disease course, activities of daily living/requirements, risks, benefits and success rate of intervention (6) |

| Underlying cause | 4 | MUA contraindicated in osteoporosis |

| Recurrence | 3 | MUA for early recurrence following arthroscopic release; More aggressive approach |

| Bilateral disease | 2 | More aggressive approach; contralateral disease requires surgery |

| Other responses | MUA if resistant to distension; open arthrolysis used for secondary revision only; Capsular distension if general anaesthetic contraindicated; all patients excluding diabetics are treated by supervised neglect; MUA for uncomplicated Frozen Shoulder; previous dislocation then avoid MUA. If anaesthetic issues more likely to use MUA. |

Numbers in brackets corresponds to the number of respondents expanding on the issue, MUA Manipulation Under Anaesthesia.

Figure 1.

The most common components of surgery used by participants during Arthroscopic Arthrolysis. Please note, participants were allowed to choose more than one answer.

M/IG/ACR Middle/Inferior Glenohumeral/Anterior Capsular Release.

Discussion

The aim of the study was to determine current trends in the treatments utilised for frozen shoulder amongst surgical members of the BESS. Such information would help identify commonly used treatments, the cost effectiveness of which may then be tested with prospective high quality comparative trials.

Management of frozen shoulder can be surgical or non-surgical. The disease is often self-limited with a natural history of about 15 to 20 months25. Physiotherapy is a popular nonsurgical treatment especially in the stiffness phase, despite the lack of high quality evidence to support its use. Some studies have shown that low grade physiotherapy programmes (movements within the comfort zone) may show better long term outcome as compared to high intensity (movements at the limits of pain tolerance) programmes26, 27. Intra-articular steroid injections may be more effective during the inflammatory phase of the disease28, 29. However their effects maybe short lived29. Hydrodilation involves the injection of fluid into the joint cavity with the aim of stretching and tearing the capsule. Early studies have reported successful results with this technique6. Regardless of what form of nonoperation intervention used and despite the benign natural history of the disease, some patients fail to achieve desired outcomes with non-operative management.

Surgical treatments may provide long term improvement but may carry surgery related risks. Manipulation under anaesthesia involves the passive tearing of thickened contracted inflamed ligaments and capsule. It carries a risk of bone fractures, tendon and labrum tears but may rapidly improve movement range29–31. Arthroscopic and open release may also involve the risk of wound infection, and neurovascular injury. As confirmed by our study arthroscopic arthrolysis is the most popular surgical intervention and has been previously shown to confer lasting long term improvements in symptoms32. As our study suggest there is a wide variation in the way in which arthroscopic artholysis is carried out ranging from partial release to a full 360 degree release. To our knowledge there are no current consensus guidelines on which subtype of this procedure is the most effective. Open capsular release is generally indicated for the failure of other modes of treatment and for extra-capsular contractures or where arthroscopic surgical expertise is not available29, 32–34.

Our results suggest that physiotherapy and steroid injections are the 2 most commonly used treatments prior to proceeding with surgery. Capsular distension, although used less often, is still utilised by a substantial number of respondents. When it came to surgery, arthroscopic arthrolysis and manipulation under anaesthesia were the two most commonly used treatments with only a small minority utilising open surgical release. As expected with increased utilisation of arthroscopic techniques, arthroscopic arthrolysis was used by 88.5% of respondents versus 47% using manipulation under anaesthesia.

What was interesting with regards to the choice of non-surgical and surgical treatments is that a substantial proportion of respondents based their choice on personal experience or training rather than published clinical evidence. This may reflect the attitudes of health professionals in making their treatment choices on the fact that good results are available for the various treatment modalities but may also reflect the lack of high quality comparative studies in setting guidelines for treatment.

Decision making and approach to surgical and non-surgical management of the stiffness predominant phase of frozen shoulder was further explored when participants were asked whether their approach is influenced by any factors (Tab. 3). Amongst the factors that influenced the approach to management was frozen shoulder secondary to diabetes, severity of symptoms, chronicity of symptoms as well as response to other treatments. These were factors which favoured a surgical approach. It also became clear that, given the natural history of gradual improvement of frozen shoulder, discussion with the patient played a key role in approach to treatment.

When it comes to arthroscopic arthrolysis previously described surgical techniques vary from isolated rotator interval release to a 360° all round release. Release of the intrarticular part of subscapularis as well as subacromial bursectomy or acromioplasty along with surgical release have also been described. Capsular release accompanied by manipulation, in order to avoid using electrocautery close to the inferior part of the glenoid in proximity to the axillary nerve, may also be performed. Most of the participants in this study reported performing rotator interval release, anterior release to the 6 o’clock position of the glenoid or short of that and completed by manipulation, as well as superior capsular release. What is interesting to note, is that a substantial proportion of participants also perform a superior release of the inter-articular part of subscapularis as well as posterior release and subacromial bursectomy. These responses clearly demonstrate that arthroscopic arthrolysis is not a uniformly performed procedure but varies amongst different surgeons and this must be taken into account in studies comparing surgery versus other modalities. The role of the various components of arthrolysis in altering and influencing the effectiveness of this procedure remains to be established. Future comparative studies exploring arthrolysis versus other surgical techniques must clearly state the components of arthrolysis being performed.

A previous study by Dennis et al.35 looked at the practice of health professionals (general practitioners, physiotherapists and orthopaedic surgeons) in managing idiopathic frozen shoulder in the painful as well as resolution phase. Conservative treatment in the form of watchful waiting, patient education, oral pain killers and steroids as well as physical therapy emerged as the most commonly used interventions for patients in the early painful phase. 47% of respondents recommended surgery for patients in the resolution phase, with 24.1% recommending arthroscopic capsular release, 21% manipulation under anaesthesia and 2% open capsular release. 19.4% recommended physical therapy, 5.1% arthrographic distension, 2.6% injections and 12.4% conservative treatment for the resolution phase. Respondents from that survey reported that longevity of symptoms and failure to respond to previous treatments should be considered when deciding whether or not to proceed with surgery.

The main limitation of our study was the response rate. Nevertheless the total numbers of respondents was 88 which is high, especially if one considers the majority of those are experts in the field surveyed based on their overall level of experience. Moreover, a gold standard cut off percentage has yet to be established for survey data, and indeed numerous studies have established that a low response rate has little or no effect on the overall accuracy of survey data36–39.

Conclusion

The management of frozen shoulder amongst shoulder surgeons varies, both with regards to non-surgical and surgical options. A substantial proportion of surgeons base their choice of treatment on personal experience and training rather than published evidence. Our results support the need for high quality clinical trials to compare the treatment options available to the shoulder surgeon.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the research committee of BESS for its invaluable help in this study.

References

- 1.Walker-Bone K, Palmer KT, Reading I, Coggon D, Cooper C. Prevalence and impact of musculoskeletal disorders of the upper limb in the general population. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;51(4):642–651. doi: 10.1002/art.20535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reeves B. Stages of Frozen Shoulder 4. Scand J Rheumatol. 1975:193–196. doi: 10.3109/03009747509165255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hanchard NC, Goodchild L, Thompson J, O’Brien T, Davison D, Richardson C. Evidence-based clinical guidelines for the diagnosis, assessment and physiotherapy management of contracted (frozen) shoulder: quick reference summary. Physiotherapy. 2012;98(2):117–120. doi: 10.1016/j.physio.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hand C, Clipsham K, Rees JL, Carr AJ. Long-term outcome of frozen shoulder. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(2):231–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2007.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robinson CM, Seah KT, Chee YH, Hindle P, Murray IR. Frozen shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94(1):1–9. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.94B1.27093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vastamäki H, Kettunen J, Vastamäki M. The natural history of idiopathic frozen shoulder: a 2- to 27-year follow up study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(4):1133–1143. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-2176-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buchbinder R, Green S, Youd JM, Johnston RV, Cumpston M. Arthrographic distension for adhesive capsulitis (frozen shoulder) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(1):CD007005. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Celik D. Comparison of the outcomes of two different exercise programs on frozen shoulder. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2010;44(4):285–292. doi: 10.3944/AOTT.2010.2367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diwan DB, Murrell GA. An evaluation of the effects of the extent of capsular release and of postoperative therapy on the temporal outcomes of adhesive capsulitis. Arthroscopy. 2005;21(9):1105–1113. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2005.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gasparre G, Fusaro I, Galletti S, Volini S, Benedetti MG. Effectiveness of ultrasound-guided injections combined with shoulder exercises in the treatment of subacromial adhesive bursitis. Musculoskelet Surg. 2012;96(Suppl. 1):S57–61. doi: 10.1007/s12306-012-0191-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharma S. Management of frozen shoulder – conservative vs surgical? Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2011;93(5):343–344. doi: 10.1308/147870811X582080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thomas WJ, Jenkins EF, Owen JM, et al. Treatment of frozen shoulder by manipulation under anaesthetic and injection: does the timing of treatment affect the outcome? J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93(10):1377–1381. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B10.27224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Favejee MM, Huisstede BM, Koes BW. Frozen shoulder: the effectiveness of conservative and surgical interventions—systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2011;45(1):49–56. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.2010.071431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jerosch J. 360 Degrees arthroscopic capsular release in patients with adhesive capsulitis of the glenohumeral joint-indication, surgical technique, results. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2001;9(3):178–186. doi: 10.1007/s001670100194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jerosch J, Nasef NM, Peters O, Mansour AM. Mid-term results following arthroscopic capsular release in patients with primary and secondary adhesive shoulder capsulitis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s00167-012-2124-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lafosse L, Boyle S, Kordasiewicz B, Guttierez-Arramberi M, Fritsch B, Meller R. Arthroscopic arthrolysis for recalcitrant frozen shoulder: a lateral approach. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(7):916–923. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2011.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Le Lievre HM, Murrell GA. Long-term outcomes after arthroscopic capsular release for idiopathic adhesive capsulitis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94(13):1208–1216. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.00952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Musil D, Sadovský P, Stehlík J, Filip L, Vodicka Z. Arthroscopic capsular release in frozen shoulder syndrome. [Article in Czech] Acta Chir Orthop Traumatol Cech. 2009;76(2):98–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ozbaydar MU, Tonbul M, Altun M, Yalaman O. Arthroscopic selective capsular release in the treatment of frozen shoulder. [Article in Turkish] Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2005;39(2):104–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Snow M, Boutros I, Funk L. Posterior arthroscopic capsular release in frozen shoulder. Arthroscopy. 2009;25(1):19–23. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Warner JJ, Allen A, Marks PH, Wong P. Arthroscopic release for chronic, refractory adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78(12):1808–1816. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199612000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maund E, Craig D, Suekarran S, et al. Management of frozen shoulder: a systematic review and cost-effectiveness analysis. Health Technol Assess. 2012;16(11):1–264. doi: 10.3310/hta16110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park KD, Nam HS, Kim TK, Kang SH, Lim MH, Park Y. Comparison of Sono-guided Capsular Distension with Fluoroscopically Capsular Distension in Adhesive Capsulitis of Shoulder. Ann Rehabil Med. 2012;36(1):88–97. doi: 10.5535/arm.2012.36.1.88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Padulo J, Oliva F, Frizziero A, Maffulli N. Muscles, Ligaments and Tendons Journal. Basic principles and recommendations in clinical and field science research. MLTJ. 2013;4:250–252. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vastamäki H, Kettunen J, Vastamäki M. The natural history of idiopathic frozen shoulder: A 2- to 27-year follow up study. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2012;470(4):1133–1143. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-2176-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Russell S, Jariwala A, Conlon R, Selfe J, Richards J, Walton M. A blinded, randomized, controlled trial assessing conservative management strategies for frozen shoulder. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery/American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons. 2014;23(4):500–507. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2013.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jain TK, Sharma NK. The effectiveness of physiotherapeutic interventions in treatment of frozen shoulder/adhesive capsulitis: A systematic review. Journal of Back and Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation. 2014;27(3):247–273. doi: 10.3233/BMR-130443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Blanchard V, Barr S, Cerisola FL. The effectiveness of corticosteroid injections compared with physiotherapeutic interventions for adhesive capsulitis: A systematic review. Physiotherapy. 2010;96(2):95–107. doi: 10.1016/j.physio.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bloom JE, Rischin A, Johnston RV, Buchbinder R. Image-guided versus blind glucocorticoid injection for shoulder pain. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2012;8 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009147.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clement RGE, Ray AG, Davidson C, Robinson CM, Perks FJ. Frozen shoulder: Long term outcome following arthrographic distension. Acta Orthopaedica Belgica. 2013;79(4):368–374. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grant JA, Schroeder N, Miller BS, Carpenter JE. Comparison of manipulation and arthroscopic capsular release for adhesive capsulitis: A systematic review. Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery/American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons. 2013;2013;22(8):1135–1145. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2013.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Walther M, Blanke F, Von Wehren L, Majewski M. Frozen shoulder—comparison of different surgical treatment options. Acta Orthopaedica Belgica. 2014;80(2):172–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maund E, Craig D, Suekarran S, et al. Management of frozen shoulder: A systematic review and cost-effectiveness analysis. Health Technology Assessment (Winchester, England) 2012;2012;16(11):1–264. doi: 10.3310/hta16110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.D’Orsi GM, Via AG, Frizziero A, Oliva F. Treatment of adhesive capsulitis: A review. Muscles, Ligaments and Tendons Journal. 2012;2(2):70–78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dennis L, Brealey S, Rangan A, Rookmoneea M, Watson J. Managing idiopathic frozen shoulder: a survey of health professionals’ current practice and research priorities. Shoulder and Elbow. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Groves RM. Nonresponse rates and nonresponse bias in household surveys. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2006;70(5):646–675. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Keeter S, Kennedy C, Dimock M, Best J, Craighill P. Gauging the impact of growing nonresponse on estimates from a national RDD telephone survey. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2006;70(5):759–779. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Visser PS, Krosnick JA, Marquette J, Curtin M. Mail surveys for election orecasting? An evaluation of the columbus dispatch poll. Public Opinion Quarterly. 1996;60(2):181–227. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Groves RM, Peytcheva E. The impact of nonresponse rates on nonresponse bias: A meta-analysis. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2008;72(2):167–189. [Google Scholar]