Abstract

Objective:

The objective of this study was to evaluate the incidence of adverse effects reported by adolescents following 14 days of use of a mouthrinse containing 0.05% NaF+0.12% chlorhexidine.

Methods:

This double-blind study was developed as part of a randomized clinical trial. The adolescents enrolled to the study were randomly divided into two groups to use either: 0.05% NaF+0.12% chlorhexidine (G1, n=85) or 0.05% NaF (G2, n=85). Both groups used a 10mL solution of the mouthwash during 1 minute daily for 2 weeks under supervision. After that period, the subject's acceptance of taste was measured using a verbal descriptive scale (Labeled Magnitude Scale - LMS)11. Participants were also interviewed regarding the occurrence of possible adverse effects during treatment (temporary palate disorders, tooth staining or unpleasant taste). The proportional differences between the groups were tested using the chi-square test.

Results:

Palate changes were reported by 26% of participants of each group; 17.7% of G1 and 32% of G2 reported an unpleasant taste (p = 0.062), while staining was reported by 55% of G1 and 68.9% of G2 (p = 0.117). Absenteeism rates were similar in both groups (G1= 2.58 ± 2.69; G2=2.81 ± 2.39), p=0.362.

Conclusion:

adherence was high in both groups and side effects reported by subjects were not perceived by them as being important. Since subjects' acceptance and compliance is fundamental to the success of an oral health program, chlorhexidine-fluoride could be a useful resource in a program of plaque control.

Keywords: Mouthwashes; Chlorhexidine, adverse effects; Randomized clinical trials

Abstract

Objetivo:

Este estudo se propôs a calcular taxa de efeitos adversos após 14 dias de uso de solução de bochecho de NaF 0,05% + clorexidina 0,12% realizados por adolescentes.

Métodos:

Este estudo duplo-cego foi desenvolvido como parte de um ensaio clínico randomizado. Os adolescentes foram divididos aleatoriamente em dois grupos: NaF 0,05% + clorexidina 0,12% (G1) ou NaF 0,05%, (G2) de 85 estudantes cada que bochecharam diariamente, 10mL de solução sob supervisão, durante 1 minuto, por 2 semanas. Após esse período, a aceitação dos participantes ao gosto das soluções foi avaliada através de uma escala descritiva verbal - (LMS)11. Os participantes foram entrevistados também quanto a possíveis efeitos adversos acontecidos durante tratamentos (desordens temporárias de paladar, manchamento dental e o gosto de soluções desagradáveis). As diferenças entre proporções em ambos os grupos foram testadas pelo teste do qui-quadrado.

Resultados:

Alteração de paladar foi informada por 26% dos estudantes de cada grupo; 17,7% dos G1 e 32% do G2 notaram o gosto desagradável (p = 0,062); manchas foram observadas por 55% dos G1 e 68,9% dos G2 (p = 0,117) e, as taxas de absenteísmo foram semelhantes (G1 = 2,58±2,69; G2=2,81(2,39), p=0,362.

Conclusão:

A aderência dos participantes foi alta e os efeitos colaterais percebidos não pareceram importantes pelos adolescentes nos dois grupos. Implicação prática: porquanto a aceitação e aderência dos participantes são fundamentais para o sucesso de um programa de saúde bucal, a associação da clorexidina-fluoreto poderia ser um recurso adicional favorável dentro de um programa de controle de placa.

INTRODUCTION

The chemical control of plaque can be a useful resource in a subgroup of patients whose mechanical control becomes difficult and ineffective2,7,15,16. An antimicrobial agent should inhibit the adhesion stage of bacterial colonization, and affect the growth and metabolic activity of dental plaque, without, however, interfering with any other biological process. In addition, its toxicity must be low, since such solutions could be inadvertently swallowed24. The enhancement of the cariostatic effect of the fluoride by its combination with antimicrobial agents has been suggested16 and this combination has been shown to be effective in arresting caries lesions in irradiated patients with minimal salivary buffering capacity due to lower saliva flow rates16

Chlorhexidine is the most commonly used antimicrobial substance because of its proven efficacy in altering membrane function, controlling oral biofilm and inhibiting the metabolism of microorganisms. In addition, it interferes with the acid production of dental plaque, reducing the pH level during cariogenic challenges22.

On the other hand, chlorhexidine is known to cause certain adverse effects directly related to higher concentrations25, long-term regimens13,25, and undisturbed biofilm. Consumption of some chromogenic agents17, such as coffee or tea, for example, may also increase toothstaining17, which is one of the most recognized problems associated with chlorhexidine. Cationic antiseptics, such as chlorhexidine, may activate anionic chromatic particles contained in some food and drinks, causing interaction with tooth surfaces1. In vitro, these colored particles can produce identically colored complexes such as those caused by chlorhexidine and observed clinically in individuals who drink tea, coffee or red wine compared with those who do not ingest these drinks17. Randomized controlled clinical trials have shown that tea and coffee associated with the use of chlorhexidine mouthrinses contribute significantly to staining the teeth and tongue. On the other hand, abstaining from tea and coffee notably reduces this effect17.

In addition, the bitter taste of chlorhexidine and the temporary reduction in the subjects' perception of bitterness and saltiness4,10 could compromise their adherence to a program based on this antiseptic. Moreover, loss of taste could reduce patients' capacity to distinguish possible toxic foods, and may decrease their appetite. However, no serious adverse effects associated with the use of chlorhexidine mouthrinse have been reported in clinical trials24.

However, there is a paucity of data in the scientific literature concerning the incidence of adverse effects reported by subjects using a mouthrinse containing 0.12% chlorhexidine and 0.05% sodium fluoride in a single solution. This association has been used as an adjunct to oral hygiene15, in the control of active carious infection in high-risk patients2, in handicapped children7, orthodontic patients5,21, irradiated patients16, lymphoma patients receiving cytostatic drugs19, persons with disabilities7,18 and in the elderly9,20,23. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to estimate the prevalence and intensity of adverse effects in patients using a mouthrinse containing 0.05% sodium fluoride or the combination of 0.12% chlorhexidine solution and 0.05% sodium fluoride after fourteen days of use.

METHODS

This current study was part of a larger, therapeutic, randomized, double-blind, clinical trial whose main objective was to compare the effectiveness of 0.05% sodium fluoride alone (NaF) and the combination of 0.12% chlorhexidine solution (CHX) and 0.05% sodium fluoride in arresting active carious lesions after 14 school days12. Carried out within the randomized clinical trial, the objective of this study was to evaluate the occurrence of side effects during the use of these mouthrinses. The study was carried out in a public school in Florianópolis, capital of the Brazilian state of Santa Catarina.

Individual selection and eligibility criteria

Children with at least one active white spot carious lesion in smooth enamel surfaces were enrolled to the study. Exclusion criteria comprised schoolchildren who were taking some medication, those in use of orthodontic brackets or dental prosthesis, those who had undergone aesthetic tooth restoration, and pregnant or breastfeeding girls. A sample size of 71 individuals, 11-15 years of age, was required for each group. An additional fifteen percent was added to each group to compensate for possible dropouts; therefore, 82 individuals were enrolled to each group. The Epi Info software program8 was used to calculate sample size. The criterion for statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Personnel and Training

Eight previously trained dental students, supervised by a dental PhD student (MLRJ), provided both groups with mouthrinses in identical plastic cups. Three dental students, also previously trained, asked the children questions regarding their perception of adverse effects. Dental students and the children were blinded with respect to the contents of the solution.

Randomization and blinding

A double-blind study was carried out and subjects were randomly allocated to one of two groups: Group 1 (G1 − 0.05% NaF + 0.12% CHX) or Group 2 (G2- 0.05% NaF). A randomization method was used to form the groups. A number was given to each eligible child and then put into a sealed opaque envelope. The envelopes were randomly selected by the supervisor (MLRJ) to allocate the individuals to each group of mouthrinsing solution, either 0.05% fluoride or 0.05% plus 0.12% chlorhexidine. Two pure solutions containing the same pharmacological formulation were used, the only difference being the presence or absence of 0.12% chlorhexidine in solutions A and B, respectively12. The solutions were in identical, unlabeled, amber-colored bottles, bearing only the codes A or B. Neither the eligible children, the mouthrinsing supervisors or the examiners knew to which group the children belonged.

Dental examinations were carried out at baseline and after fourteen days of treatment. Prior to the examinations, the children were asked to brush their teeth under the supervision of the dental students using toothbrushes provided by the study.

Mouthrinsing

The children were instructed by the team to rinse during 1 minute/day for 14 consecutive school days using the 10 mL solution provided in plastic cups. The components common to the two solutions were 0.05% sodium fluoride, glycerin, non-cariogenic anise aroma, blue food coloring, preservative and vehicle (qsp). The solutions were prepared exclusively for the study (Fórmula & Ação, São Paulo) and both solutions had identical color, flavor and artificial taste. The toothbrushing was performed without the use of toothpaste since Brazilian dentifrices contain SLS (sodium lauryl sulfate), which inactivates CHX, thereby requiring a minimum interval of 30 minutes between toothbrushing and rinsing3, which would be an unreasonable interruption of the schoolchildren's routine. Although an effect of fluoridated water, concentration of water fluoridated and dentifrice in the arrestment of dental caries was expected, both groups were randomly exposed to these variables and any influence should therefore have been distributed randomly.

Interviews

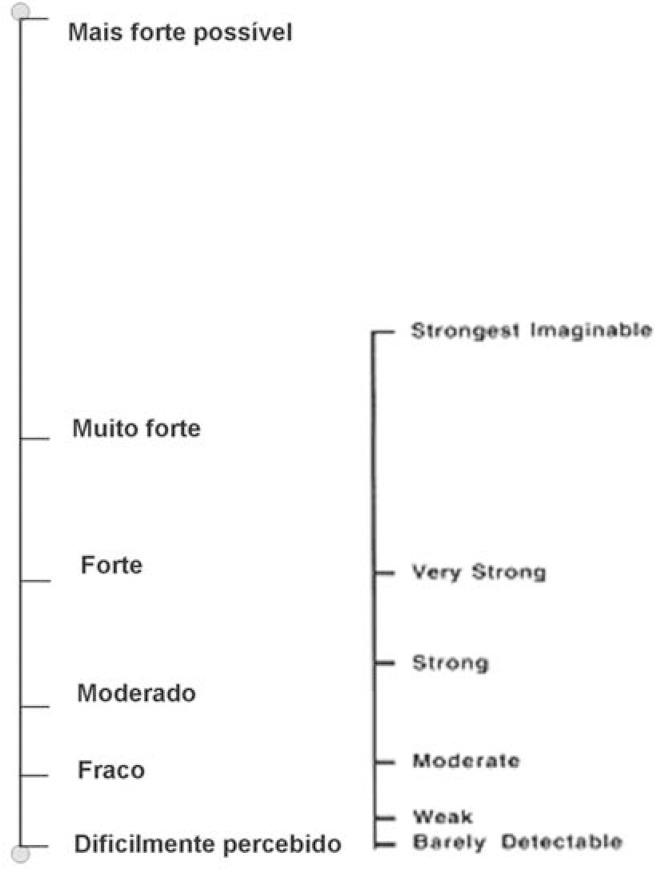

To evaluate subjects' perception of the side-effects caused by either treatment, only one examiner (RMF), who was aware of the objectives of the study, carried out all the interviews. After 14 days of rinses, the children were screened for their ability to assign a bitterness intensity rating to each solution, using a simplified scale based on the "Labeled Magnitude Scale" (LMS)11. The method used to estimate the impact caused by side effects related to the solutions was subjective. However, the instrument used is an adaptation of the Labeled Scale Measurement (LSM) that has been widely used in physiological science11. The instrument underwent previous validation in the Portuguese language and was adapted to the local culture to ensure optimal comprehension by the study population (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. LMS) Labeled measurement scale.

This scale is a method used for obtaining estimates of intensity. The method consists of a line (usually vertical) with verbal descriptions of intensity, using adjectives to describe intensity that ranged from weak, moderate, strong and very strong to the strongest imaginable sensation. Afterwards, the adolescents stated whether the perceived intensity was acceptable or not. They were also asked about possible adverse effects occurring during or after that period, such as transitory alterations in the patient's perception of taste during or following the test period, any change in the appearance of teeth perceived by the subjects, as well as questions related to weekly consumption of staining products such as tea, coffee, colored snacks, Coca-Cola®, other soft drinks, cigarettes and chocolates. Stain was evaluated in a dichotomy way considering its presence or not after the test period. All natural teeth in the dentition were included.

Data analysis

To test the methodology, a pre-test was performed in a sample of 30 adolescents, whose characteristics were similar to those of the study population. Absenteeism was measured daily and was defined as being when a student failed to carry out the scheduled mouthrinsing or did not attend the final clinical examination.

Both dental examinations were carried out by the same examiner (ARDG). After the second dental examination, all new tooth staining that had not been registered at the first examination was recorded. The examiner did not know to which group the adolescents belonged.

The Mann-Whitney U and Chi-square tests were used to assess differences in variables between the two groups at baseline and at the end of the trial. The differences between proportions were tested using the chi-square test and comparison in the perception of tooth staining was analyzed using Fisher's exact test. Significance was established when p<0.05. The SPSS software package (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA) was used for the data analysis.

RESULTS

Eighty-five adolescents were enrolled in each group and participated in the study. There were no statistically significant differences in gender or age between adolescents in the test group (0.05% sodium fluoride combined with 0.12% chlorhexidine – G1) and those in the control group (0.05% sodium fluoride mouthrinse alone – G2), (Table 1). Absenteeism, which could have modified the results, was almost identical in the two groups studied (Table 1).

TABLE 1. Differential aspects of both groups at baseline.

| Characteristics | G1 (n=85)(%) | G2 (n=85) (%) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female participants | 55.3 | 58.8 | 0.64 * ns |

| Age (years) – mean (SD) | 13.01 (1.34) | 12.96 (1.38) | 0.88** ns |

| Absenteeism – mean (SD) | 2.58(2.69) | 2.81(2.39) | 0.362** ns |

ns: not significant

SD: Standard deviation;

Chi-square test;

Mann-Whitney U test

Temporary taste disorders were perceived by exactly 26% of students in each group; unpleasant taste by 17.7% of participants of G1 and 32.3% of G2 (p = 0.062), and staining by 55% of G1 and 68.9% of G2 (p = 0.117), (Table 2). The staining was easily removed by professional dental prophylaxis.

TABLE 2. Chi-square test for the perception of the side effects on both groups.

| Reported Side Effect % | G1 (n=85) (%) |

G2 (n=85) (%) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temporary taste disorders | 26 | 26 | ns | |

| Unpleasant taste | 17.7 | 32.3 | 0.062 | ns |

| Staining | 55 | 68.9 | 0.117 | ns |

Significant (p < 0.05)

ns: not significant

There was no difference in the consumption of colored snacks, chocolates, juices, Coca-Cola®, other soft drinks, tea or colored flavoring between the two groups. However, coffee consumption was higher in the test group (G1) than in the control group (G2). The consumption of tea was slightly higher among participants in the control group compared to the test group (Table 3). None of the subjects reported current tobacco use.

TABLE 3. Mann Whitney U test for the consumption frequency of possible staining agents reported by the adolescents.

| Food/beverage | G1 Mean (SD) | G2 Mean (SD) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colored Snacks | 2.00 (0.30) | 2.57 (0.28) | 0.194 |

| Chocolate | 2.58 (0.30) | 2.89 (0.32) | 0.499 |

| Juices | 3.67 (0.32) | 3.40 (0.33) | 0.623 |

| Coca-Cola® | 3.64 (0.27) | 3.37 (0.23) | 0.264 |

| Other soft drinks | 3.00 (0.33) | 2.80 (0.30) | 0.477 |

| Coffee | 3.69 (0.43) | 4.77 (0.36) | 0.037* |

| Tea | 1.03 (0.26) | 0.46 (0.17) | 0.075 |

| Colored seasoning | 2.67 (0.47) | 3.34 (0.46) | 0.233 |

Significant (p < 0.05)

Regarding patients' perception of tooth staining, there was in ten cases, a discrepancy between theirs and the dentist's opinion. The dentist has noticed the tooth staining more frequently than the adolescent (Table 4). Brown stain was usually found on the cervical third of anterior teeth.

TABLE 4. Fisher's exact test for the comparison of dentist's and subjects' perception of tooth staining.

| Dentist's perception of tooth staining | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| yes | no | ||||

| Subjects' perception of tooth staining | yes | n | 6 | 6 | |

| % perceived | 100% | 100% | |||

| no | n | 10 | 19 | 29 | |

| % perceived | 34.5% | 65.5% | 100% | ||

| Total | n | 16 | 19 | 35 | |

| % perceived | 45.7% | 54.3% | 100% | ||

DISCUSSION

Considering the widespread use of chlorhexidine in dentistry, there are few reports of side effects, other than some local effects such as discoloration of teeth, tongue, restorations and dentures1,14,17,25, and temporary taste disorders, especially related to the 0.2% rinses4,9. It is difficult to compare the results of this present study with those from previous randomized clinical trials due the variability of fluoride and chlorhexidine combinations, concentrations, pharmaceutical presentation (gels, varnishes or rinses), and the presence or not of both elements in the same product. In a previous randomized clinical trial (RCT)16, chlorhexidine associated with fluoride in the same product achieved excellent patient acceptance and adherence in a daily mouthrinse program (0.05% NaF - 0.2% CHX) and tooth staining was not reported by the users of chlorhexidine. In another study, staining was intensified after 6 months of use of 1% CHX-F toothpaste, but the program participants considered the local side effects acceptable25. The acceptability and tolerability of chlorhexidine and benzydamine oral rinse agents used in a protocol on oral hygiene in children receiving chemotherapy was evaluated and both agents were acceptable and well-tolerated by children over the age 6 years old6. However, these studies used different regimes from those used in the current trial.

In this study, subject absenteeism was very low and did not differ between the two groups, indicating high adherence to the program. It is, therefore, reasonable to speculate that the use of CHX-F could be recommended as an adjunct procedure for plaque control.

A similar number of subjects in both groups (26%) reported temporary taste disorders, reflecting the successful randomization procedure. A greater proportion of subjects using the fluoridated solution (G2), (32.3%) reported an unpleasant taste when compared to those in the CHX-F solution group (G1), (17.7%), indicating that the anise flavor contained in both solutions successfully masked any unpleasant taste. Moreover, the subjects reported the taste as being strong but refreshing and stated that it gave them the sensation of oral cleanliness. In addition, the adolescents perceived the changes in tooth color as being something positive, probably associated with the therapeutic effect of the two substances.

There was no significant difference between the two groups with respect to the consumption of any of the staining agents investigated (Table 3), demonstrating the homogeneity of the two groups. Coffee consumption was higher than tea consumption in both groups and there was a discretely higher consumption in the chlorhexidine-fluoride group. These results hindered the comparison with previous studies in which coffee was shown to stain teeth less than tea17. Cigarette smoking was not mentioned by any subject in either group.

To demonstrate whether tooth staining was correlated with the solution, the perception of the subjects themselves was compared with the perception of the study dentist. All the tooth staining perceived by the dentist was caused by the chlorhexidine rinse, and these results are in agreement with previous reports1,15,17, confirming chlorhexidine as a tooth-staining agent. On the other hand, although the adolescents reported the occurrence of a few cases of tooth staining, it did not seem important to them and did not affect their participation in the program.

Another aspect that should be considered is the possibility of the participants being psychologically biased in favor of the treatment. However, this possibility is minimal since participants were just as likely to be randomized to either treatment group.

Therefore, the inherent characteristics of the study design, such as randomization and blinding (subjects, dental examiner and interviewer), which avoided any bias in variables, confirm its suitability and validate our findings. For the same reason, the occurrence of tooth staining was recorded during the dental examinations in an effort to guarantee that only tooth staining relative to the treatment was analyzed. Another positive feature of the study design is the adequate sample size that enables the results to be extrapolated to a larger population and confers external validity to the study. Finally, it is important to emphasize that the length of time spent in this study was sufficient to observe positive effect of CLX-F on arrestment of active caries lesions12, with a high compliance rate in both groups and no relevant side effects.

CONCLUSIONS

Adherence was high in both groups and side effects perceived by subjects did not appear relevant to them. Since patient compliance was considered highly satisfactory and the side effects perceived by the subjects did not seem important to them, the use of chlorhexidine combined with fluoride may be recommended as an auxiliary resource in plaque control.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by FUNPESQUISA (337/2002, UFSC, Brazil). The authors would like to thank the dental students who helped them during the fieldwork and Ana Nere Santos for her technical support. The authors would also like to thank the local education authorities and teachers. Condor S.A. kindly provided the toothbrushes used in the study. As the solutions were specifically prepared for the study, there was no conflict of interest that could influence the results.

REFERENCES

- 1.Addy M, Mahdavi SA, Loyn T. Dietary staining in vitro by mouthrinses as a comparative measure of antiseptic activity and predictor of staining in vivo. J Dent. 1995;23(2):95–99. doi: 10.1016/0300-5712(95)98974-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anusavice KJ. Chlorhexidine, fluoride varnish, and xylitol chewing gum: underutilized preventive therapies? Gen Dent. 1998;46(1):34-8, 40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barkvoll P, Rolla G, Svendsen K. Interaction between chlorhexidine digluconate and sodium lauryl sulfate in vivo . J Clin Periodontol. 1989;16(9):593–595. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1989.tb02143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breslin PA, Tharp CD. Reduction of saltiness and bitterness after a chlorhexidine rinse. Chem Senses. 2001;26(2):105–116. doi: 10.1093/chemse/26.2.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buyukyilmaz T, Ogaard B, Dahm S. The effect on the tensile bond strength of orthodontic brackets of titanium tetrafluoride (TiF4) application after acid etching. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1995;108(3):256–261. doi: 10.1016/s0889-5406(95)70018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng KKF. Children's acceptance and tolerance of chlorhexidine and benzydamine oral rinses in the treatment of chemotherapy-induced oropharyngeal mucositis. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2004;8(4):341–349. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2004.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chikte UM, Pochee E, Rudolph MJ, Reinach SG. Evaluation of stannous fluoride and chlorhexidine sprays on plaque and gingivitis in handicapped children. J Clin Periodontol. 1991;18(5):281–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1991.tb00429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dean AG, Dean JA, Coulombier D, Brendel KA, Smith DC, Burton AH, et al. Center of Disease Control on Prevention, World Health Organization. Epi Info, version 6: a word processing data base and statistics program for epidemiology on microcomputers [software] Atlanta: OPAS/WHO; 1994. 589 Atlanta, Georgia; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erickson L. Oral health promotion and prevention for older adults. Dent Clin North Am. 1997;41(4):727–750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frank ME, Gent JF, Hettinger TP. Effects of chlorhexidine on human taste perception. Physiol Behav. 2001;74(1-2):85–99. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(01)00558-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Green BG, Shaffer GS, Gilmore MM. Derivation and evaluation of a semantic scale of oral sensation magnitude with apparent ratio properties. Chem Senses. 1993;18(6):683–702. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guimarães ARD, Peres MA, Vieira RS, Ramos-Jorge M L, Modesto A. Efficacy of two mouth rinsing solutions on arresting non-dental cavitated decay lesions: a randomised clinical trial. [Abstract 4] Caries Res. 2004;38(4):358–358. [presented in 51st ORCA Congress - European Organisation of Research for Caries Research, June 30–July 3, 2004, Marburg, Germany] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hase JC, Attstrom R, Edwardsson S, Kelty E, Kisch J. 6-month use of 0.2% delmopinol hydrochloride in comparison with 0.2% chlorhexidine digluconate and placebo. (I). Effect on plaque formation and gingivitis. J Clin Periodontol. 1998;25(9):746–753. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1998.tb02516.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jenkins S, Addy M, Newcombe R. The effects of a chlorhexidine toothpaste on the development of plaque, gingivitis and tooth staining. J Clin Periodontol. 1993;20(1):59–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1993.tb01761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joyston-Bechal S, Hernaman N. The effect of a mouthrinse containing chlorhexidine and fluoride on plaque and gingival bleeding. J Clin Periodontol. 1993;20(1):49–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1993.tb01759.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Katz S. The use of fluoride and chlorhexidine for the prevention of radiation caries. J Am Dent Assoc. 1982;104(2):164–170. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1982.0016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leard A, Addy M. The propensity of different brands of tea and coffee to cause staining associated with chlorhexidine. J Clin Periodontol. 1997;24(2):115–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1997.tb00476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mann J, Wolnerman JS, Lavie G, Carlin Y, Garfunkel AA. Periodontal treatment needs and oral hygiene for institutionalized individuals with handicapping conditions. Spec Care Dentist. 1984;4(4):173–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1754-4505.1984.tb00358.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meurman JH, Laine P, Murtomaa H, Lindqvist C, Torkko H, Teerenhovi L, et al. Effect of antiseptic mouthwashes on some clinical and microbiological findings in the mouths of lymphoma patients receiving cytostatic drugs. J Clin Periodontol. 1991;18(8):587–591. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1991.tb00094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Niessen LC, Gibson G. Oral health for a lifetime: Preventive strategies for the older adult. Quintessence Int. 1997;28:626–630. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ogaard B, Larsson E, Henriksson T, Birkhed D, Bishara SE. Effects of combined application of antimicrobial and fluoride varnishes in orthodontic patients. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2001;120(1):28–35. doi: 10.1067/mod.2001.114644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rolla G, Melsen B. On the mechanism of the plaque inhibition by chlorhexidine. J Dent Res. 1975;54:57–62. doi: 10.1177/00220345750540022601. Spec N° B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simons D, Kidd EA, Beighton D, Jones B. The effect of chlorhexidine/xylitol chewing-gum on cariogenic salivary microflora: a clinical trial in elderly patients. Caries Res. 1997;31(2):91–96. doi: 10.1159/000262382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Rijkom HM, Truin GJ, van't Hof MA. A meta-analysis of clinical studies on the caries-inhibiting effect of chlorhexidine treatment. J Dent Res. 1996;75(2):790–795. doi: 10.1177/00220345960750020901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yates R, Jenkins S, Newcombe R, Wade W, Moran J, Addy M. A 6month home usage trial of a 1% chlorhexidine toothpaste (1). Effects on plaque, gingivitis, calculus and toothstaining. J Clin Periodontol. 1993;20(2):130–138. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1993.tb00327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]