Abstract

The activation of carbon–carbon (C–C) bonds is an effective strategy in building functional molecules. The C–C bond activation is typically accomplished via metal catalysis, with which high levels of enantioselectivity are difficult to achieve due to high reactivity of metal catalysts and the metal-bound intermediates. It remains largely unexplored to use organocatalysis for C–C bond activation. Here we describe an organocatalytic activation of C–C bonds through the addition of an NHC to a ketone moiety that initiates a C–C single bond cleavage as a key step to generate an NHC-bound intermediate for chemo- and stereo-selective reactions. This reaction constitutes an asymmetric functionalization of cyclobutenones using organocatalysts via a C–C bond activation process. Structurally diverse and multicyclic compounds could be obtained with high optical purities via an atom and redox economic process.

Activation of C–C bonds is a powerful method for directly functionalizing organic molecules, but is still a challenging task. Here, the authors show that N-heterocyclic carbenes can activate the C–C bonds in cyclic ketones, allowing the enantioselective formation of lactams.

Activation of C–C bonds is a powerful method for directly functionalizing organic molecules, but is still a challenging task. Here, the authors show that N-heterocyclic carbenes can activate the C–C bonds in cyclic ketones, allowing the enantioselective formation of lactams.

The catalytic activation of a carbon–carbon (C–C) single bond of cyclobutenones can provide direct methods towards building useful molecules1,2,3,4,5. Despite the rather clear practical significance, C–C bond activation remains challenging. Traditionally, this process is initiated by the oxidative addition of a transition metal catalyst to the C–C bond followed by other bond breaking and formation events (Fig. 1a). Due to the high reactivities of the metal catalyst and the metal-bound intermediates, chemoselectivity is generally difficult to control. In addition, it still remains difficult to achieve high levels of enantioselectivity using the transition metal-catalysed C–C bond activation approach6,7,8,9,10,11. In many cases, intramolecular reactions were used to overcome the challenging selectivity issues.

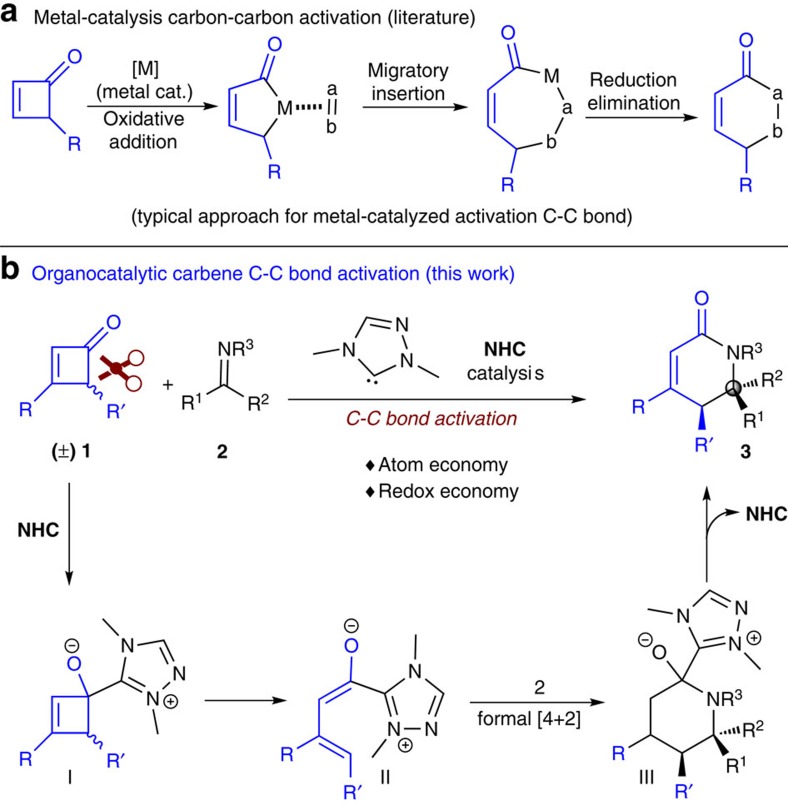

Figure 1. NHC-catalysed cyclization via carbon–carbon bond activation of ketones.

(a) Metal-catalysed activation of carbon–carbon bond. (b) Our synthetic proposal via an organocatalysis. NHCs react with cyclobutenone to generate chiral vinylenolate intermediate to give novel formal cycloaddition reactions.

Our laboratory is interested in developing organocatalysis for challenging bond activations while maintaining the power of organocatalysis for chemo- and stereo-selectivity control. Herein, we report the addition of an N-heterocyclic carbene (NHC) organocatalyst to a ketone moiety that initiates a C–C single bond cleavage to generate an NHC-bound intermediate for chemo- and stereo-selective reactions (Fig. 1b). Compared with the earlier NHC catalysis (such as oxidative NHC catalysis for γ-carbon functionalization of enals)12,13,14,15,16,17,18, in this approach all atoms of the substrate end up in the product (atom economy) and the overall reaction is redox-neutral (redox economy)19. Specifically, the addition of an NHC catalyst to an unsaturated four-membered cyclo-ketone substrate to form intermediate I. Breaking a C–C bond of the four-membered ring eventually generates a vinyl enolate intermediate12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22 II that reacts with an imine substrate to form the lactam product. NHC catalysis is routinely used in the activation of aldehydes through the formation of Breslow intermediates23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32. The addition of NHC catalyst to ketone moiety for reactions is much less studied, except for the activation of α-hydroxyl ketones via retro-benzoin pathways as nicely illustrated by Bode and co-workers33,34.

Our interest in aza-quaternary center compounds35 with important biological activity motivated us to use four-membered cyclo-ketone substrate (1a) and imine (2a) as model substrates for the search of suitable catalytic conditions (Table 1). As an important note, although four-membered cyclo-ketones were nearly untouched in organocatalysis, this class of molecules caught considerable attentions in the field of transition metal catalysis (Fig. 1a). Murakami et al.36,37 have pioneered the non-enantioselective C–C bond activation of four-membered cyclic ketones to react with olefins in an intramolecular fashion38,39,40,41,42. Recently, impressive enantioselective intramolecular reactions enabled by the metal-catalysed C–C bond activation of four-membered cyclo-ketones were reported by the groups of Dong10 and Cramer11. The related cyclobutanol has also been used in the synthesis via C–C bond breaking to build sophisticated molecules, as illustrated by Trost,43 Tu44,45 and others43,44,45,46,47.

Table 1. Condition optimization.

Results

Reaction optimization

As briefed in Table 1, triazolium NHCs (A, B, entries 1 and 2) could smoothly mediate the formation of desired product 3a as essentially a single diastereomer. The N-aryl substituent (phenyl or mesityl) of pre-catalyst A48 and B49,50 had little effect on the reaction yield. Next the enantioselectivity of this transformation was evaluated with aminoindanol-derived triazolium salts C–F49,50,51,52 (entries 3–6). In all cases, the product 3a was formed essentially as a single diastereomer with good yields (entries 1–6). Among precatalysts C–F, the N-aryl substituents could affect the reaction enantioselectivities (entries 3–6). The use of N-mesityl substituted triazolium catalyst D48 gave the product 3a with the highest enantioselectivity (90:10 er) and good yield (84%, entry 4). We then noticed that increasing the reaction temperature to 55 °C could reduce the reaction time from 48 to 24 h and there was a small but reproducible increase of er without sacrificing the yield or er (entry 7) for unclear reasons. Interestingly, there was a small but reproducible increase of er when increasing the reaction temperature from room temperature (90:10 er, entry 4) to 55 °C (92:8 er, entry 7).

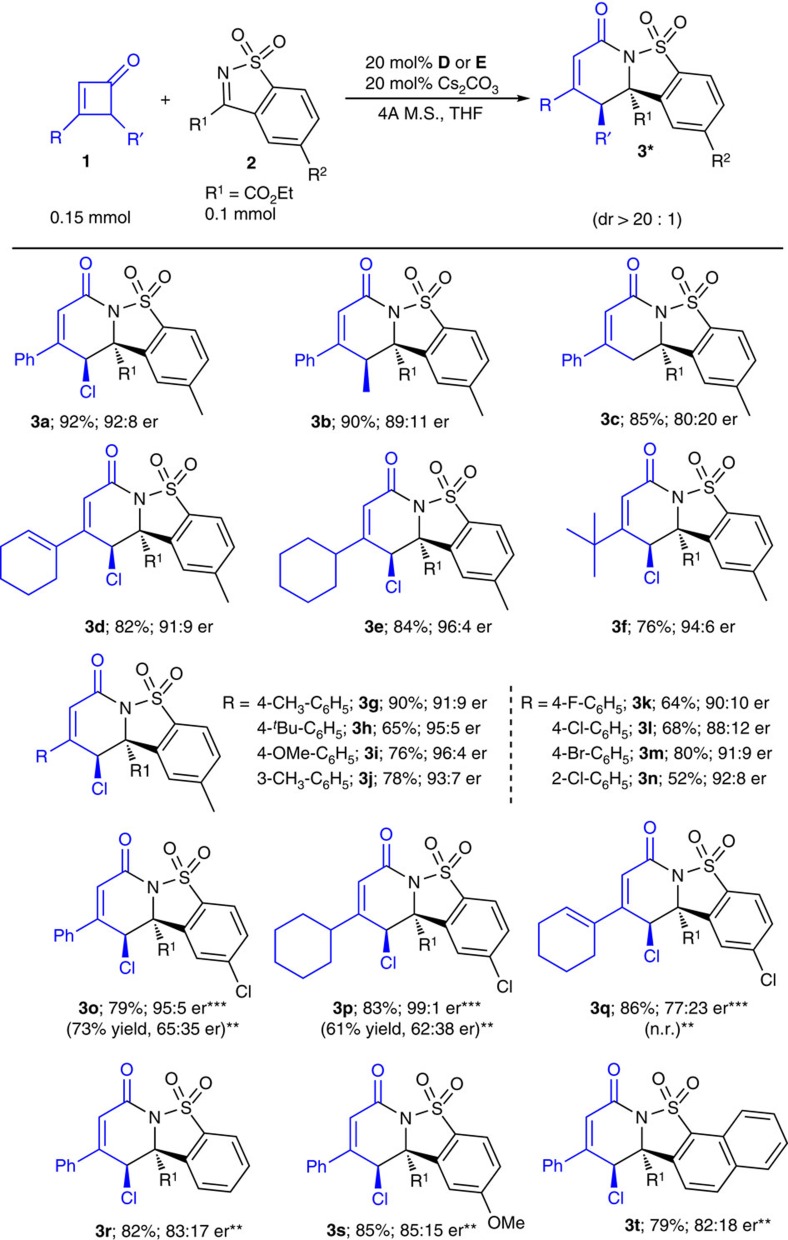

Substrates scope with sulfonyl imines

With optimized condition (Table 1, entry 7) in hand, we next evaluated the scope of this reaction (Fig. 2). The R′ substituent at the γ-carbon of cyclobutenone 1 could be Cl (3a), methyl (3b) or a proton (3c). When the R’ substituent was an aryl unit, the α,β-double bond in the four-membered ring could easily migrate to the β,γ-carbons. Placing a substituent (such as a CH3 or Cl unit) at the α-carbon of 1 led to nearly no reaction, and the ketone substrate was recovered under the reaction condition. The β-aryl group of 1 could be replaced with an alkenyl (3d), cyclohexyl (3e) or a tert-butyl (3f) substituent. Placing substituents with various electronic properties at the β-aryl group of 1 were all tolerated (3g–n). When an electron withdrawing group (Cl) was used to replace the methyl group of imine substrate 2 (3o–3q), the reaction gave good yields but much lower ers. We then found that by using the more electron-deficient NHC pre-catalyst E, the products (3o–3q) could be obtained with good to excellent enantiomeric excesses. It appears that the electronic properties of both the imine substrates and NHC catalysts could significantly affect the enantioselectivities in our reaction system53,54,55,56. For example, with the N-mesityl catalyst D as the NHC pre-catalyst, the reaction with imine 2a gave product 3a with 92:8 er; while under the same conditions the use of imine substrate with a chlorine substituent gave product 3o with 65:35 er. Similar effects with N-trichloro phenyl catalyst E were observed. When E was the catalyst, 3a was obtained with 64:36 er (Table 1, entry 5) while 3o was observed with 95:5 er. The imine substrate bearing no substituent at the phenyl group also reacted well to give 3r with good yield, albeit with lower er. Results comparable to those of 3r were observed when imines bearing a methoxylphenyl (3s) or naphthyl (3t) unit were used.

Figure 2. Reaction scope.

*The scope of this catalytic transformation was evaluated under standard conditions (Table 1, entry 7). Substrate scope includes γ- (3a–3c) and β-substituents (3d–3n) cyclobutenones (using 2a as the optimal imine), and various imines (3o–3t, using 1a as the optimal substrate). Reported yields were isolated yields of 3 based on imine 2. Diastereoselective ratio (dr of 3 was determined via 1H NMR analysis of the unpurified reaction mixture. Relative configuration of the major diastereoisomer was assigned based on X-ray structure of 3b and 3m (CCDC 988901, CCDC 988902, see Supplementary Information for more details). **The reactions were performed at 25 °C for 36 h. ***The reactions were performed using pre-catalyst E at 25 °C for 36 h (the reaction temperature was 0 °C for 3p).

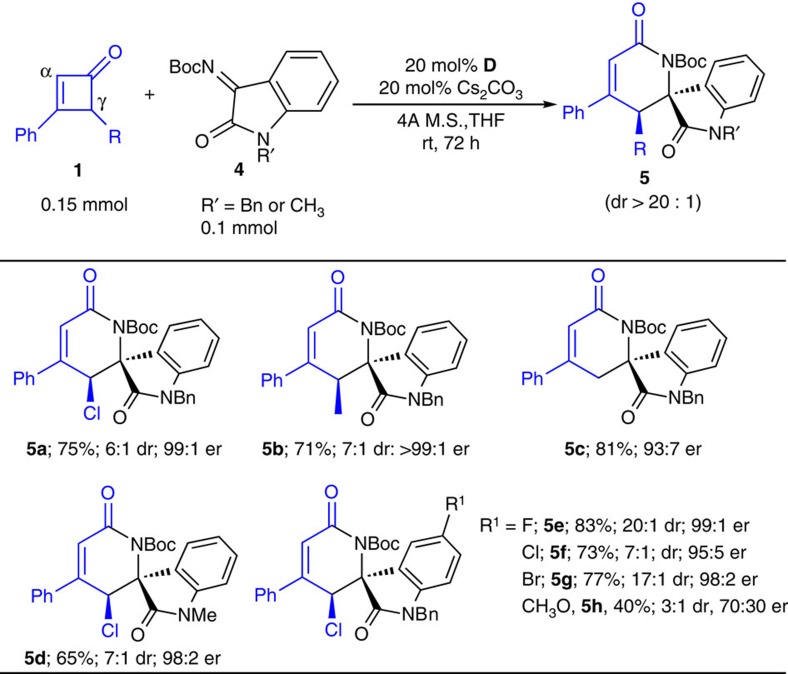

Substrates scope with isatin imines

To further explore the scope of the C–C bond activation reaction, we next examined Boc-protected imines derived from isatins to react with cyclobutenones 1 (Fig. 3). Catalyst D used in the earlier reactions (Table 1) was found effective here. Optimal results were obtained when the reactions were performed at room temperature for 72 h. The reactions proceeded to give tricyclic molecules (5a–g) containing spiro quaternary carbon centres with good drs and excellent ers. When substrate with electron-donating substituent (such as a methoxyl group, 5h) was used, a drop in both the reaction yields and stereo-selectivities were observed.

Figure 3. Reaction scope.

Substrate scope includes β-phenyl with various γ-substituents (1a–1c; using 4a as the optimal imine), and various imines (using 1a as the optimal substrate). Reported yields were isolated yields of 5 based on imine 4. Diastereoselective ratio (dr of 5 was determined via 1H NMR analysis of the unpurified reaction mixture. Relative configuration of the major diastereoisomer was assigned based on X-ray structure of 5f and 5g (CCDC 1011138 and CCDC 1011137, see Supplementary Information for more details). Ers (major diastereomer) were determined via chiral phase high-performance liquid chromatography analysis.

Discussion

These two types of reactions summarized in Figs 2 and 3 exemplified the potential value of our C–C activation strategy. The resulting products contains two contiguous stereogenic centres and one aza-quaternary center. Notably, our approach also allows for the construction of chiral carbon stereocenters bearing a Cl atom. The absolute configurations of the reaction products were determined based on their 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (1H NMR) spectra and X-ray diffraction of the products 3b, 3m, 5f and 5g.

As a note, installing substituents at the ketone β-aryl group led to a significant drop in the reaction yields with little or no enantioselectivities for the isatin imine reactions, for reasons unclear at this moment (Fig. 3). The use of other imines (such as N-tosyl imine derived from benzaldehyde or aryl trifluoroacetone) led to no detecable lactam product. The imine substrates were hydrolysed at an elongated time in our reaction system. A better understanding between the substrate structures and reactivities require further investigations.

In addition, cyclobutenones are known to undergo ring opening to form vinyl ketenes under thermal conditions. However, in our reactions such ring opening was unlikely to occur because: (a) the cyclobutenone substrates were stable (no ring opening) in the absence of carbene catalysts under our reaction condition, (b) our catalytic condition could occur at room or lower temperatures, such as synthesis of the product 3p in Fig. 2. In our reaction, the addition of carbene catalyst initiated a key C–C breaking step to generate the vinyl enolate intermediate57.

In summary, we have demonstrated the use of an NHC catalyst to catalyse the breaking of C–C single bonds for asymmetric reactions58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first example demonstrating asymmetric functionalization of cyclobutenone using organocatalyst. Structurally diverse and multicyclic compounds could be obtained with high optical purities via an atom and redox economical process. Built upon this strained four-membered ring ketone activation, we are looking into other more common ketone compounds. We also expect this study to encourage further investigations into organocatalytic strategies for new C–C activations and highly economical syntheses.

Methods

Materials

For 1H, 13C NMR and high-performance liquid chromatography spectra of compounds in this manuscript, see Supplementary Figs 1–68. For details of the synthetic procedures, see Supplementary Methods.

Syntheses of products 3 and 5

To a dry Schlenk tube equipped with a magnetic stir bar, were added cyclobuteneones 1 (0.15 mmol), imines 2 or 4 (0.1 mmol), triazolium salt D or E (0.02 mmol), Cs2CO3 (0.02 mmol, 6.5 mg) and 4A molecular sieve (100 mg). The tube was closed with a septum, evacuated and refilled with nitrogen. Then, the freshly distilled tetrahydrofuran (1.0 ml) was added. The reaction mixture was stirred at the specified temperature as showed in Fig. 2 and Fig. 3 in the text. After the complete consumption of imines by was monitoring by thin-layer chromatography, the mixture was concentrated under reduced pressure. The resulting crude residue was purified via column chromatography on silica gel to afford the desired products 3 or 5.

Author contributions

B.-S.L. conducted most of the experiments; Y.W., Z.J. and P.Z. prepared the substrates and catalysts for the reaction scope evaluation; R.G. contributed to X-ray analysis. Y.R.C. conceptualized and directed the project, and drafted the manuscript with the assistance from all the co-authors. All authors contributed to discussions.

Additional information

Accession codes: For ORTEPs of products 3b, 3m, 5f and 5g, see Supplementary Information. CCDC 988901, CCDC 988902, CCDC 1011138 and CCDC 1011137 contain supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data could be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

How to cite this article: Li, B.-S. et al. Carbon–carbon bond activation of cyclobutenones enabled by the addition of chiral organocatalyst to ketone. Nat. Commun. 6:6207 doi: 10.1038/ncomms7207 (2015).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures 1-68, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary References

Acknowledgments

Generous financial supports for this work are provided by: Singapore National Research Foundation, Singapore Economic Development Board (EDB), GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) and Nanyang Technological University (NTU), China’s National Key program for Basic Research (No. 2010CB 126105), Thousand Talent Plan, the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 21132003, No. 21472028) and Guizhou University (China).

References

- Crabtree R. H. The organometallic chemistry of alkanes. Chem. Rev. 85, 245 (1985). [Google Scholar]

- Rybtchinski B. & Milstein D. Metal insertion into C-C bonds in solution. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 38, 870 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jun C.-H. Transition metal-catalyzed carbon–carbon bond activation. Chem. Soc. Rev. 33, 610 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nečas D. & Kotora M. Rhodium-catalyzed C-C bond cleavage reactions. Curr. Org. Chem. 11, 1566 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Seiser T., Saget T., Tran D. N. & Cramer N. Cyclobutanes in catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 7740 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda T., Shigeno M. & Murakami M. Asymmetric synthesis of 3,4-dihydrocoumarins by rhodium-catalyzed reaction of 3-(2-hydroxyphenyl)cyclobutanones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 12086 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nájera C. & Sansano J. M. Asymmetric intramolecular carbocyanation of alkenes by C-C bond activation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 2452 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter C. & Krause N. Rhodium(I)-catalyzed enantioselective C-C bond activation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 2460 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiser T. & Cramer N. Enantioselective metal-catalyzed activation of strained rings. Org. Biomol. Chem. 7, 2835 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu T., Ko H. M., Savage N. A. & Dong G. Highly enantioselective Rh-catalyzed carboacylation of olefins: efficient syntheses of chiral poly-fused rings. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 20005 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Souillart L., Parker E. & Cramer N. Highly enantioselective rhodium(i)-catalyzed activation of enantiotopic cyclobutanone c-c bonds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 3001 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo J., Chen X. & Chi Y. R. Oxidative γ-addition of enals to trifluoromethyl ketones: enantioselectivity control via Lewis acid/N-heterocyclic carbene cooperative catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 8810 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Yang S., Song B. A. & Chi Y. R. Functionalization of benzylic C(sp3)-H bonds of heteroaryl aldehydes through N-heterocyclic carbene organocatalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 11134 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X.-Y., Xia F., Cheng J.-T. & Ye S. Highly enantioselective g-amination by N-heterocyclic carbene catalyzed [4+2] annulation of oxidized enals and azodicarboxylates. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 10644 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maki B. E., Chan A., Phillips E. M. & Scheidt K. A. Tandem oxidation of allylic and benzylic alcohols to esters catalyzed by N-heterocyclic carbenes. Org. Lett. 9, 371 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guin J., De Sarkar S., Grimme S. & Studer A. Biomimetic carbene-catalyzed oxidations of aldehydes using TEMPO. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 8727 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Sarkar S., Grimme S. & Studer A. NHC catalyzed oxidations of aldehydes to esters: chemoselective acylation of alcohols in presence of amines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 1190 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang P.-C. & Bode J. W. On the role of CO2 in NHC-catalyzed oxidation of aldehydes. Org. Lett. 13, 2422 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jian T.-Y., Shao P.-L. & Ye S. Enantioselective [4+2] cycloaddition of ketenes and 1-azadienes catalyzed by N-heterocyclic carbenes. Chem. Commun. 47, 2381 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiseni P. S. & Peters R. Catalytic asymmetric formation of δ-lactones by [4+2] cycloaddition of zwitterionic dienolates generated from α,β-unsaturated acid chlorides. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46, 5325 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiseni P. S. & Peters R. Lewis acid−Lewis base catalyzed enantioselective Hetero-Diels−Alder reaction for direct access to δ-lactones. Org. Lett. 10, 2019 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen L., Sun L. & Ye S. Highly enantioselective γ-amination of α,β-unsaturated acyl chlorides with azodicarboxylates: efficient synthesis of chiral γ-amino acid derivatives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 15894 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslow R. On the mechanism of thiamine action. 1V.l evidence from studies on model system. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 80, 3719 (1958). [Google Scholar]

- Enders D. & Kallfass U. An efficient nucleophilic carbene catalyst for the asymmetric benzoin condensation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 41, 1743 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burstein C. & Glorius F. Organocatalyzed conjugate Umpolung of α,β-unsaturated aldehydes for the synthesis of γ-butyrolactones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 43, 6205 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takikawa H., Hachisu Y., Bode J. W. & Suzuki K. Catalytic enantioselective crossed aldehyde–ketone benzoin cyclization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 45, 3492 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair V., Vellalath S., Poonoth M. & Suresh E. N-heterocyclic carbene-catalyzed reaction of chalcones and enals via homoenolate: an efficient synthesis of 1,3,4-trisubstituted cyclopentenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 8736 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips E. M., Wadamoto M., Chan A. & Scheidt K. A. A highly enantioselective intramolecular Michael reaction catalyzed by N-heterocyclic carbenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46, 3107 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q., Perreault S. & Rovis T. Catalytic asymmetric intermolecular stetter reaction of glyoxamides with alkylidenemalonates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 14066 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du D. & Wang Z. N-heterocyclic carbene catalyzed domino reactions of formylcyclopropane 1,1-diesters: a new synthesis of coumarins. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 4949 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du D., Li L. & Wang Z. N-heterocyclic carbene-catalyzed domino ring-opening/redox amidation/cyclization reactions of formylcyclopropane 1,1-diesters: direct construction of a 6-5-6 tricyclic hydropyrido[1,2-a]indole skeleton. J. Org. Chem. 74, 4379 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv H., Mo J., Fang X. & Chi Y. R. Formal Diels-Alder reactions of chalcones and formylcyclopropanes catalyzed by chiral N-heterocyclic carbenes. Org. Lett. 13, 5366 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang P.-C., Rommel M. & Bode J. W. α′-hydroxyenones as mechanistic probes and scope-expanding surrogates for α,β-unsaturated aldehydes in N-heterocyclic carbene-catalyzed reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 8714 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binanzer M., Hsieh S.-Y. & Bode J. W. Catalytic kinetic resolution of cyclic secondary amines. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 19698 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesma G., Landoni N., Sacchetti A. & Silvani A. The Spiroperidine-3-3′-oxindole scaffold: a type II β-turn peptide isostere. Tetrahedron 66, 4474 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Murakami M., Amii H., Shigeto K. & Ito Y. Breaking of the C–C bond of cyclobutanones by rhodium(I) and its extension to catalytic synthetic reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118, 8285 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Murakami M., Ashida S. & Matsuda T. Eight-membered ring construction by [4+2+2] annulation involving β-carbon elimination. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 2166 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cammers-Goodwi A. Tri-n-butylphosphine-catalyzed addition and ring-cleavage reactions of cyclobutenones. J. Org. Chem. 58, 7619 (1993). [Google Scholar]

- Murakami M., Miyamoto Y. & Ito Y. Dimeric triarylbismuthane oxide: a novel efficient oxidant for the conversion of alcohols to carbonyl compounds. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 6441 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magomedov N. A., Ruggiero P. L. & Tang Y. Remarkably facile hexatriene electrocyclizations as a route to functionalized cyclohexenones via ring expansion of cyclobutenones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126, 1624 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu T. & Dong G. Rhodium-catalyzed regioselective carboacylation of olefins: A C-C bond activation approach for accessing fused-ring systems. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 7567 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko H. M. & Dong G. Cooperative activation of cyclobutanones and olefins leads to bridged ring systems by a catalytic [4+2] coupling. Nat. Chem. 6, 789 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura T. & Uemura S. Palladium-catalyzed arylation of tert-cyclobutanols with aryl bromide via C−C bond cleavage: new approach for the γ-arylated ketones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 121, 11010 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang E., Fan C.-A., Tu Y.-Q., Zhang F.-M. & Song Y.-L. Organocatalytic asymmetric vinylogous α-ketol rearrangement: enantioselective construction of chiral all-carbon quaternary stereocenters in spirocyclic diketones via semipinacol-type 1,2-carbon migration. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 14626 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Z.-L., Fan C.-A. & Tu Y.-Q. Semipinacol rearrangement in natural product synthesis. Chem. Rev. 111, 7523 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trost B. M. & Yasukata T. A catalytic asymmetric Wagner—Meerwein shift. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 7162 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiser T. & Cramer N. Enantioselective C-C bond activation of allenyl cyclobutanes: access to cyclohexenones with quaternary stereogenic centers. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 9294 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sohn S. S. & Bode J. W. Catalytic generation of activated carboxylates from enals: a product-determining role for the base. Org. Lett. 7, 3873 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr M. S., Read de Alaniz J. & Rovis T. An efficient synthesis of achiral and chiral 1,2,4-triazolium salts: bench stable precursors for N-heterocyclic carbenes. J. Org. Chem. 70, 5725 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He M., Struble J. R. & Bode J. W. Highly enantioselective azadiene Diels—Alder reactions catalyzed by chiral N-heterocyclic carbenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 8418 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vora H. U. & Rovis T. Nucleophilic carbene and HOAt relay catalysis in an amide bond coupling: an orthogonal peptide bond forming reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 13796 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vora H. U., Moncecchi J. R., Epstein O. & Rovis T. Nucleophilic carbene catalyzed synthesis of 1,2-amino alcohols via azidation of epoxy aldehydes. J. Org. Chem. 73, 9727 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang M. et al. DFT study on the reaction mechanisms and stereoselectivities of NHC-catalyzed [2+2] cycloaddition between arylalkylketenes and electron-deficient benzaldehydes. Org. Biomol. Chem. 12, 6374 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies A. T., Pickett P. M., Slawin A. M. Z. & Smith A. D. Asymmetric synthesis of tri- and tetrasubstituted trifluoromethyl dihydropyranones from α-aroyloxyaldehydes via NHC redox catalysis. ACS Catal. 4, 2696 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Douglas J., Taylor J. E., Churchill G., Slawin A. M. Z. & Smith A. D. NHC-Promoted asymmetric β-lactone formation from arylalkylketenes and electron-deficient benzaldehydes or pyridinecarboxaldehydes. J. Org. Chem. 78, 3925 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Um J. M., DiRocco D. A., Noey E. L., Rovis T. & Houk K. N. Quantum mechanical investigation of the effect of catalyst fluorination in the intermolecular asymmetric stetter reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 11249 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danheiser R. L., Carini D. J. & Basak A. Trimethylsilyl)cyclopentene annulation: a regiocontrolled approach to the synthesis of five-membered rings. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 103, 1604 (1981). [Google Scholar]

- Enders D. & Balensiefer T. Nucleophilic carbenes in asymmetric organocatalysis. Acc. Chem. Res. 37, 534 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair V., Vellalath S. & Babu B. P. Recent advances in carbon-carbon bond-forming reactions involving homoenolates generated by NHC catalysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 37, 2691 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biju A. T., Kuhl N. & Glorius F. Extending NHC-catalysis: coupling aldehydes with unconventional reaction partners. Acc. Chem. Res. 44, 1182 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen D. T. & Scheidt K. A. Cooperative Lewis acid/N-heterocyclic carbene catalysis. Chem. Sci 3, 53 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossmann A. & Enders D. N-heterocyclic carbene catalyzed domino reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 314 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izquierdo J., Hutson G. E., Cohen D. T. & Scheidt K. A. A continuum of progress: applications of N-hetereocyclic carbene catalysis in total synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 11686 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar S. D., Biswas A., Samanta R. C. & Studer A. Catalysis with N-heterocyclic carbenes under oxidative conditions. Chem. Eur. J 19, 4664 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan S. J., Candish L. & Lupton D. W. Acyl anion free N-heterocyclic carbene organocatalysis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 42, 4906 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopkinson M. N., Richter C., Schedler M. & Glorius F. An overview of N-heterocyclic carbenes. Nature 510, 485 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauhan P. & Enders D. N-heterocyclic carbene catalyzed activation of esters: a new option for asymmetric domino reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 1485 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures 1-68, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary References