Abstract

Background Degenerative tendinopathy of the extensor carpi ulnaris (ECU) produced by the tip of an oversized ulnar styloid has not been formerly reported.

Case Description We report an uncommon case of an injury to the ECU tendon that was related to a prominent oversized ulnar styloid. The patient's symptoms improved following resection of the styloid process.

Literature Review Our case differs from previous reports in that it involves an uninjured oversized ulnar styloid that damaged the overlying ECU tendon with no apparent instability.

Clinical Relevance Besides ulnar styloid impaction syndrome, the diagnosis of ECU tenosynovitis should also be considered in patients with ulnar-side pain and an oversized ulnar styloid.

Keywords: extensor carpi ulnaris, tendinopathy, tenosynovitis, ulnar styloid, wrist ulnar-side pain

Oversized ulnar styloids are known to produce ulnar styloid impaction syndrome due to chronic impingement of this structure against the triquetrum.1 However, the implication of an extra-large ulnar styloid as a causative factor for a tendinopathy of extensor carpi ulnaris (ECU) has not been described.

The reported causative factors for ECU tendinopathy include erosions of the floor of the sixth compartment; subsheath attenuation or rupture; osteophytes; prominent ulnar ridge; and even ulnar styloid nonunion.2

We report a patient with an ECU tendinopathy located at the tip of an oversized ulnar styloid whose symptoms subsided after its partial removal.

Case Report

The patient was a 54-year-old right-handed woman without a history of trauma, repetitive motion, or sport activity. She presented with insidious pain on the ulnar side of the right wrist that had gradually increased over the preceding 4 years. For the preceding 2 years, her pain was unresponsive to anti-inflammatory medication and physical therapy. Immobilization with a wrist splint provided partial pain relief.

On physical examination, there was tenderness at the tip of the ulnar styloid and at the fovea. The pain was aggravated with supination, flexion, and ulnar deviation, and there was tenderness over the ECU tendon at the wrist level. Pain was also elicited with forced ulnar deviation in pronation and supination and with the Ruby test to evaluate ulnar styloid impaction syndrome (passive supination with the wrist extended). No signs of ECU dislocation were seen with isometric forced supination.

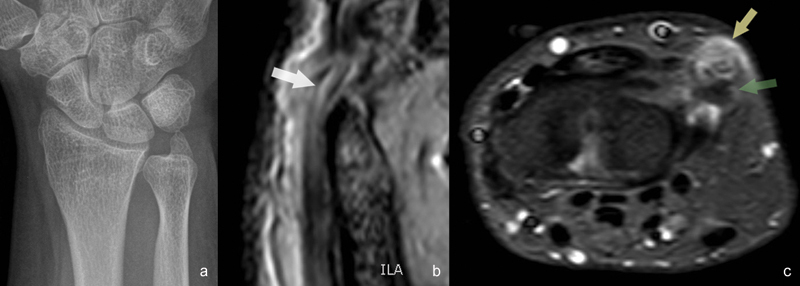

The X-rays showed an ulnar styloid measuring 7.4 mm with an ulnar styloid process index (USPI)3 of 0.43 (normal value of 0.21 ± 0.07). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed an important tenosynovitis at the area of the ECU tendon where it hooks around the ulnar styloid (Fig. 1). We could not see signs of impingement between the tip of the styloid and the triquetrum.

Fig. 1a–c.

(a) Anteroposterior (AP) radiograph showing oversized ulnar styloid. (b) T2-weighted sagittal MRI image showing internal longitudinal lesions (white arrow) where the ECU tendon hooks around the ulnar styloid. (c) STIR-weighted axial MRI image showing important tenosynovitis (yellow arrow) at the tip of the ulnar styloid (green arrow).

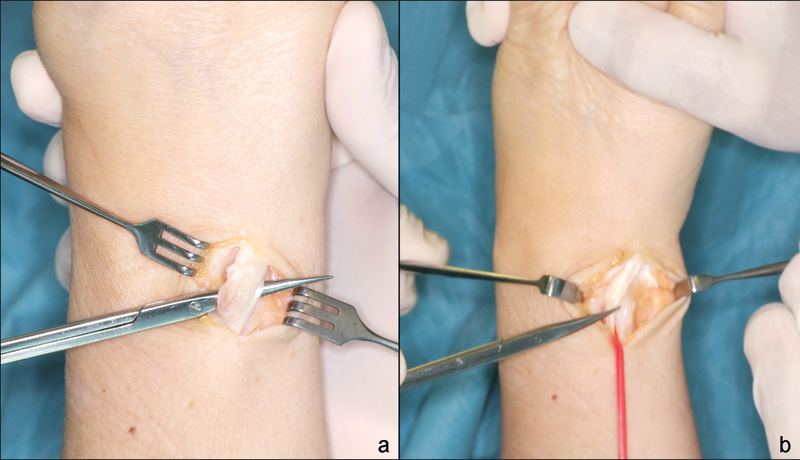

The patient was taken for surgery. Through a longitudinal incision, the retinaculum over the sixth compartment and the ECU subsheath were divided at its radial side. The tendon was found to be enlarged and torn on its undersurface at the level of the tip of the ulnar styloid (Fig. 2). We did not find any erosions, bony prominences over the ulnar surface, or attenuation of the tendon subsheath that could cause instability. The patient did not exhibit any signs of triquetrum chondromalacia either.

Fig. 2a, b.

Intraoperative aspect. (a) Longitudinal lesions in the undersurface of the ECU tendon localized at the tip of the ulnar styloid; (b) No signs of subluxation were seen.

The ulnar styloid was partially removed along with smoothing of its dorsal surface, taking care not to disrupt the foveal insertion of the radioulnar ligaments. A thorough tenosynovectomy was performed. The subsheath and the sixth retinaculum were used to cover the floor of the sixth compartment and sutured to the periosteum of the ulnar head. A sling consisting of the distal half of the fourth and fifth retinaculum was used to recreate the roof and avoid subluxation of the ECU tendon, as described by Spinner and Kaplan.4 Postoperatively, a wrist splint was used and removed 4 weeks later. No physical therapy was needed.

Symptoms improved completely and the patient returned to her regular activities without limitations one month after the operation. This was confirmed at her last follow-up visit 4 years later.

Discussion

Oversized ulnar styloids are known to cause ulnar styloid impaction syndrome. In their original description, Topper et al reported on eight patients whose diagnosis were based on a USPI greater than 0.21 and pain reproduced with Ruby test.1 Those criteria were met in our patient, although we could not find signs of triquetral chondromalacia at surgical inspection.

Pain at the ulnar side of the wrist, especially at the fovea and over the ECU tendon, is very common. Sometimes diagnosis imaging studies are normal and we have to rely on history and physical examination to find a diagnosis, sometimes presumptive, to solve the case. Association of an oversized ulnar styloid and ulnotriquetrum impingement syndrome is common in our practice. In the setting of negative imaging studies, removal of the ulnar styloid may confirm the diagnosis if history and physical examination are compatible. Nevertheless, in these cases, a precise direct link can never be established.

Regarding this patient, it was evident that the ECU tendon was longitudinally disrupted at the tip of the ulnar styloid, although we did not find any rough surface at the bone level. We believe that these findings and the absence of contralateral involvement would rule out an inflammatory condition and confirm the hypothesis of a mechanical factor.

There is an anatomical relationship between the ulnar styloid and the ECU tendon. Anatomical dissections by Taleisnik et al found that in supination the tendon moved out of its groove to hang over the ulnar styloid.5 According to Crimmins and Jones, as the forearm rotates, the ECU tendon remains fixed proximally along the ulnar groove in the sixth compartment but must glide over the ulnar styloid more distally to allow full rotation.6

However, to the best or our knowledge, there are no reports describing an oversized ulnar styloid producing an ECU tenosynovitis. It is unknown whether the lack of reports is due to the absence of objective findings that confirm the diagnosis. Chun and Palmer reported a patient whose symptoms were believed to be produced by an attenuated ECU subsheath that allowed the ECU to subluxate over a prominent ulnar ridge.7 Nachinolcar and Khanolkar reported on 64 cases operated on for what they described as stenosing tenovaginitis of the ECU, as an analogy with de Quervain tenosynovitis.8 In their brief report, they comment that movement of the wrist causes friction at the site of angulation around the ulnar styloid, but they did not report specific lesions caused by the tip of the styloid, oversized styloids, or treatment with a styloidectomy. Uniform good results were obtained with simple excision of the sixth compartment retinaculum. ECU postoperative instability was not reported.

In our case, as we found that the ulnar styloid created a longitudinal cut at the deeper surface of the tendon, we believed that leaving this structure intact and simply releasing or removing the subsheath was not an option, as continuous normal gliding through the styloid tip would continue to damage the tendon. As the subsheath was enlarged after trimming of the ECU, we decided to stabilize it with a Spinner-Kaplan procedure to minimize any risk of instability.

More recent data states there is no relationship between the length of the ulnar styloid and ECU lesions. Chang et al, analyzing the morphology of the distal ulna head with MRI in 71 adults with ECU pathology, found a significant correlation between negative ulnar variance and a shallower ECU groove with ECU pathology, as compared with 46 controls. They also included measurements of the ulnar styloid length, which ranged between 2.2 and 7.2 mm in the control group and 3.3 and 8.4 mm in the ECU pathology group. However, this difference was not statistically significant.9 Perhaps a larger series would be necessary to confirm this trend.

For a tendon to be damaged by an abnormal oversized bony structure, environmental factors must play a role. Together with the size of the ulnar styloid and the prominent ridge, we believe that some kind of repetitive, strenuous activity triggered the clinical picture in our patient. However, the patient cannot remember any kind of activity that could put the ECU in stress.

Our case differs from previous reports in that it involves an uninjured oversized ulnar styloid that damaged the overlying ECU tendon with no apparent instability. Removal of the injuring bone and tenosynovectomy completely relieved symptoms. Therefore, the diagnosis of ECU tenosynovitis should also be considered in patients with ulnar-side pain and an oversized ulnar styloid.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest None

References

- 1.Topper S M, Wood M B, Ruby L K. Ulnar styloid impaction syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. 1997;22(4):699–704. doi: 10.1016/S0363-5023(97)80131-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allende C, Le Viet D. Extensor carpi ulnaris problems at the wrist—classification, surgical treatment and results. J Hand Surg [Br] 2005;30(3):265–272. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsb.2004.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garcia-Ellis M Dorsal fractures of the triquetrum–avulsionor compression fracturews? Clin Orthop Relat Res 19706868124–129.5414710 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spinner M, Kaplan E B. Extensor carpi ulnaris. Its relationship to the stability of the distal radio-ulnar joint. J Hand Surg. 1987;12A:266–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taleisnik J, Gelberman R H, Miller B W, Szabo R M. The extensor retinaculum of the wrist. J Hand Surg Am. 1984;9(4):495–501. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(84)80100-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crimmins C A, Jones N F. Stenosing tenosynovitis of the extensor carpi ulnaris. Ann Plast Surg. 1995;35(1):105–107. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199507000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chun S, Palmer A K. Chronic ulnar wrist pain secondary to partial rupture of the extensor carpi ulnaris tendon. J Hand Surg Am. 1987;12(6):1032–1035. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(87)80105-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nachinolcar U G, Khanolkar K B. Stenosing tenovaginitis of extensor carpi ulnaris: brief report. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1988;70(5):842. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.70B5.3192595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang C Y, Huang A J, Bredella M A, Kattapuram S V, Torriani M. Association between distal ulnar morphology and extensor carpi ulnaris tendon pathology. Skeletal Radiol. 2014;43(6):793–800. doi: 10.1007/s00256-014-1845-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]