Abstract

Although bradykinin (BK) and insulin like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) have been shown to modulate the functional and structural integrity of the arterial wall, the cellular mechanisms through which this regulation occurs is still undefined. The present study examined the role of second messenger molecules generated by BK and IGF-1 that could ultimately result in proliferative or anti-proliferative signals in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC).

Activation of BK or IGF-1 receptors stimulated the synthesis and release of prostacyclin (PGI2) leading to increased production of cAMP in VSMC. Inhibition of p42/p44mapk or src kinases prevented the increase in PGI2 and cAMP observed in response to BK or IGF-1, indicating a role for these kinases in the regulation of cPLA2 activity in the VSMC. Inhibition of PKC failed to alter production of PGI2 in response to BK, but further increased both p42/p44mapk activation and the synthesis of PGI2 produced in response to IGF-1. In addition, both BK and IGF-1 significantly induced the expression of c-fos mRNA levels in VSMC, and this effect of BK was accentuated in the presence a cPLA2 inhibitor. Finally, inhibition of cPLA2 activity and/or cyclooxygenase activity enhanced the expression of collagen I mRNA levels in response to BK and IGF-1 stimulation.

These findings indicate that the effect of BK or IGF-1 to stimulate VSMC growth is an integrated response to the activation of multiple signaling pathways. Thus, the excessive cell growth that occurs in certain forms of vascular disease could reflect dysfunction in one or more of these pathways.

INTRODUCTION

Vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) proliferation and deposition of extracellular matrix are characteristic of progressive atherosclerotic lesions (1). Vascular injury leading to endothelial dysfunction is often a contributing factor (2, 3). Multiple growth factors and hormones have the potential to stimulate growth of VSMCs (4, 5) and may play a role in the evolution of atherosclerotic vascular disease. Alternatively, locally-generated signaling molecules such as nitric oxide and PGI2 act to antagonize cell growth and matrix deposition (6–9). The balance of signaling by such opposing influences will determine the proliferative state of the VSMC under different physiological and pathophysiological conditions.

Mitogen activated protein kinases (MAPKs) represent a family of serine-threonine kinases that are rapidly activated in response to growth factor stimulation. In mammalian cells these include the extracellular regulated kinases 1 and 2 (ERK1 and ERK2 or p44MAPK and p42MAPK), the c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase or JNK, and p38MAPK (10). These kinases integrate multiple signal inputs and activated MAPKs are capable of phosphorylating a variety of diverse targets including effector kinases and transcription factors involved in the regulation of genes associated with cellular proliferation and hypertrophy (11). MAPK activation has been linked to neointimal proliferation in response to arterial injury (12). On the other hand, nitric oxide and PGI2 are generally released by the vascular endothelium to stimulate production of cGMP and cAMP (6, 7, 13) by VSMCs and inhibit ornithine decarboxylase activity (8), actions that serve to attenuate injury-or growth factor-induced cellular proliferation.

All components of the kallikrein/kinin system have been localized within the vascular wall. Kallikrein is expressed in isolated arteries and veins and by VSMCs (14, 15). Kininogen, the substrate for kinin generation by kallikrein activity, kininase and B2 kinin receptors are also present in the VSMC (16). The physiological action of kinins is to relax the arterial blood vessel through synthesis and release of nitric oxide from the vascular endothelium (17). However, in vascular injury where endothelial integrity is lost, kinins can act to constrict the VSMC and promote cellular proliferation (18). Similarly, VSMCs express and secrete IGF-1 (19). IGF-1 is a weak mitogen for VSMCs (20) and enhances the effects of other growth factors (21, 22). Moreover, IGF-1 and IGF-1 receptor mRNA are increased in injury-induced proliferation of VSMCs (23) and overexpression of IGF-1 leads to hyperplasia of smooth muscle cells in mouse aorta (24). Thus, locally generated kinins and IGF-1 may act in an autocrine fashion to influence vascular function.

In the present study, we tested the hypothesis that BK and IGF-1 activate both proliferative and anti-proliferative pathways in VSMC and that the mitogenic effect of these molecules is a complex integrated response. The effects of BK and IGF-1 on the activation of early response signaling pathways in primary cultures of rat aortic smooth muscle cells. Each molecule stimulated MAPK activity in VSMCs through similar, though not identical, second messenger mechanisms. In addition, both BK and IGF-1 acted on the VSMC to increase PGI2 production, leading to elevated cAMP levels and consequent attenuation of BK-induced c-fos expression as well as BK and IGF-1-induced collagen I expression. The results indicate that the proliferative response of VSMCs to BK or IGF-1 stimulation reflects the integration of multiple signaling processes.

METHODS

Cell Culture

Rat aortic VSMC from male Sprague-Dawley rats (Charles-River, Laboratories, Wilmington, MA) were prepared by a modification of the method of Majack et al (25). A 2-cm segment of artery cleaned of fat and adventitia was incubated in 1 mg/ml collagenase for 3h at room temperature. The artery was then cut into small sections and fixed to a culture flask for explantation in minimal essential media (MEM) containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS), 1% non-essential amino acids, 100 mU/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml Streptomycin. Cells were incubated at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 95% air −5% CO2. Medium was changed every 3–4 days and cells were passaged every 6–8 days by harvesting with trypsin-EDTA. VSMC were identified by the following criteria. They stained positive for intracellular cytoskeletal fibrils of actin and smooth muscle cell specific myosin and negative for factor VIII antigens. VSMC isolated by this procedure were homogeneous and were used in all studies between passages 2–6.

MAPK Assay

Quiescent VSMC stimulated with BK (10−8 M) and/or IGF-1 (10−8 M)for 5 min. were suspended in 250 μl of lysis buffer (20 mM Tris, 130 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 10 mM Chaps, 1 mM PMSF, 2 mM Na Vanadate, 100 mU/ml aprotinin, 0.15 mg/ml benzamidine, pH 8.0), sonicated for 10 sec and centrifuged at 13,000g for 10 min. 25–30 μg of cytosolic fraction was analyzed by SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and the separated proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes and immunoblotted with anti-phospho-MAPK polyclonal antibody that detects p42 and p44 MAPK only when activated by phosphorylation at Thr202 and Tyr204 (1:1000 dilution, Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA). Immunoreactive bands were visualized using the ECL reagent (Amersham Corp.) according to the procedure described by the supplier.

Determination of cAMP

Serum starved VSMC sub-cultured into 24-well culture dishes were stimulated with BK (10−8 M) and/or IGF-1 (10−8M) for 10 min at 37°C. After the stimulation period the media was removed and the cells were incubated at 4°C for 10 min in 0.1 N HCl to extract intracellular cAMP. The acid extract was then analyzed for cAMP by radioimmunoassay, sensitivity of 10 pg (26).

Determination of Prostacyclin

VSMC cultured in 6-well plate dishes were serum deprived for 24 h followed by stimulation with either BK (10−8 M) or IGF-1 (10−8 M) for 10 min at 37°C. The release of 6-keto-PGF1α the stable metabolite of PGI2 into the media was measured by RIA (sensitivity 25pg) as performed previously (27). Aliquots of 50 μl and 100 μl were added to the RIA tube and then antibody and [3H] 6-keto-PGF1α were added (final volume 6-keto-PGF1α, 450 μl). After incubation for 24 h, the free [3H] 6-keto-PGF1α was separated from the bound [3H] 6-keto-PGF1α using 1ml of charcoal-dextran solution and the bound [3H] 6-keto-PGF1α was counted in liquid scintillation counter.

RNA extraction and Northern Blotting and Real-Time PCR

Quiescent VSMC grown in 15-cm plates were stimulated with BK (10−8M) for 30 min. Total RNA from the cells was extracted by the Tri reagent Method. RNA yield was determined spectrophotometrically (Ultraspec III, Pharmacia) by absorbance at 260 nm.

Total RNA (20μg) obtained as described above was denatured at 65°C for 15 min, and ran on a 1.5 % agarose gel. The gel was stained with ethidium bromide to determine the position in each lane of the 28S and 18S ribosomal RNA and to demonstrate, that similar amounts of intact RNA was used for each sample. Total RNA was transferred from the gel to Nytran membrane filters by a Possiblot Pressure Transducer (Stratagene, La Jolla, Ca) and hybridized at 60°C for 18–24 h with a c-fos cDNA probe labeled with 32P by random priming. The hybridized membranes were washed and exposed to film. Autoradiographs (Kodak XAR-5 film, Eastern Kodak, Rochester, New York) of the membranes were obtained scanned and the intensities of the bands were quantified by a microdensitometer.

Total RNA (2μg) was converted to cDNA using MLV Reverse Transcriptase (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer’s protocol at 37°C for 1 hr. To determine the validity of primers and appropriate Tm for Real Time PCR, the primers were first amplified in a PCR reaction to ensure that only one band is amplified. The following primers were designed so that all of the PCR products are within 75–150 bp (Integrated DNA Technologies Inc). Collagen I: 5′-CAC ACA TCC TGT GTC TCT TCC CAT-3′; 5′-GAT CAA GCA TAC CTC GGG TTT CCA-3′. s-actin:5′-ACT GCC GCA TCC TCT TCC TC-3′;5′-CCG CTC GTT GCC AAT AGT GA-3′.

For each target gene, a standard curve was established. This was achieved by performing a series of 3-fold dilutions of the gene of interest. Negative control was made using the same volume of Rnase-free water instead of sample. The master mix was prepared as follows: 2× SYBR Green Supermix (cat.No. 170-8880, BIO-RAD) 12.5μl, forward and reverse primer 0.25μl respectively and ddH2O 12μl. For each well, 22μl of master mix was loaded first, followed by 3μl of sample, and mixed well to get total reaction volume of 25μl. For plate setup, SYBR-490 was chosen as fluorophore. The plate was covered with a sheet of optical sealing film. PCR conditions were 95°C for 3 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 sec, 58°C for 1 min (for β-actin and Collagen I), then 95°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1 min and 100 cycles of 55°C for 10 sec. All of the reactions were done in duplicate. The correlation coefficient is between 0.99–1; PCR efficiency is between 80–120%. The mRNA levels were expressed relative to β-actin. Realtime PCR using iCycle™ iQ optical system software (version 3.0a).

Protein Determination

The concentration of protein was determined by the method of Lowry (28) with bovine serum albumin as the standard.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ±SE and were analyzed by analysis of variance ANOVA, and by Student’s t-test for two-tailed unpaired analysis. Differences were considered significant if P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Regulation of MAPK activation and prostacyclin (PGI2) synthesis by BK and IGF-1 in VSMC

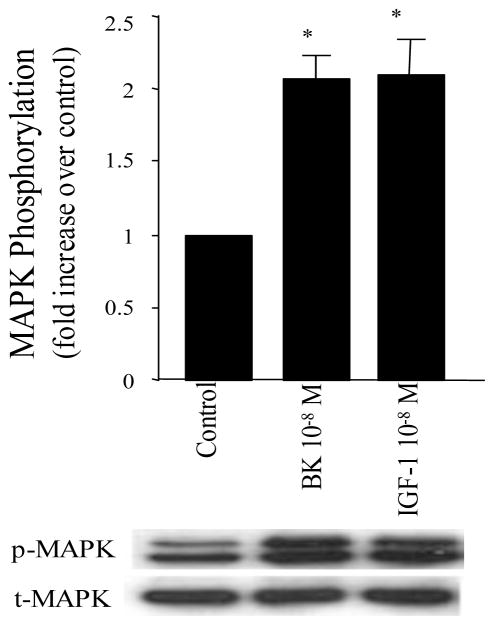

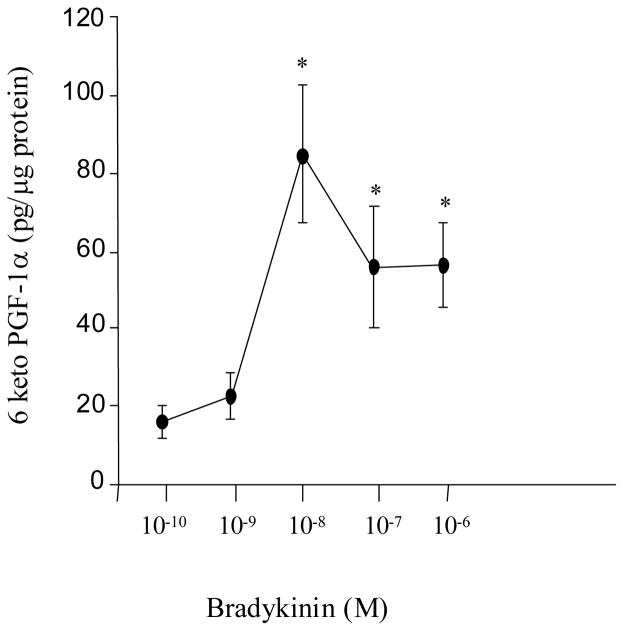

To examine the effects of either BK or IGF-1 on MAPK activation and PGI2 synthesis in VSMC, cells were serum-starved for 24 hours and then stimulated with BK or IGF-1. MAPK activation was measured as an increased phosphorylation of ERK1 (p44mapk) and ERK2 (p42mapk). Treatment of quiescent VSMCs for 10 min with BK or IGF-1 produced approximately a two-fold increase in phosphorylation of both p44mapk and p42mapk compared to that observed in unstimulated control cells (Figure 1, P<0.05, n=8 experiments). To examine effects on PGI2 synthesis, release into the incubation medium of the stable metabolite of PGI2, 6-keto-PGF1α, was measured by RIA. In figure 2, serum-deprived VSMC cultured in 6-well plates were treated with various concentrations of BK (10−10–10−6 M) for 10 min. BK stimulated the release of 6-keto-PGF1α into the culture media in a concentration-dependent manner with a peak response at 10−8 M (P<0.05, n=8 experiments). Similar results were obtained with IGF-1.

Figure 1. Activation of MAPK by BK and/or IGF-1.

VSMC were stimulated with either BK (10−8 M) and/or IGF-1 (10−8 M) for 10 min. Cell proteins were separated with SDS-PAGE. MAPK phosphorylation (p42mapk and p44mapk) were measured by immunoblot using anti-phosphotyrosine-MAPK antibodies (p-MAPK) and total MAPK was measured in the same immunoblot by stripping the membrane and re-immunoblotting with anti-total MAPK antibodies (t-MAPK). Data are expressed as mean±SE and the bar graphs are representative of 6 separate experiments. * P<0.05 vs. control.

Figure 2. Concentration-dependent effects of BK on PGI2 (6-keto-PGF1α) production in VSMC.

Serum starved VSMC were stimulated with BK (10−10–10−6 M) for 10 min., and the release of 6-keto-PGF1α into the media was measured by RIA. BK produced a concentration dependent increase in 6-keto-PGF1α with a peak response at 10−8M. The figure is representative of 8 separate experiments. *P<0.05 vs. basal.

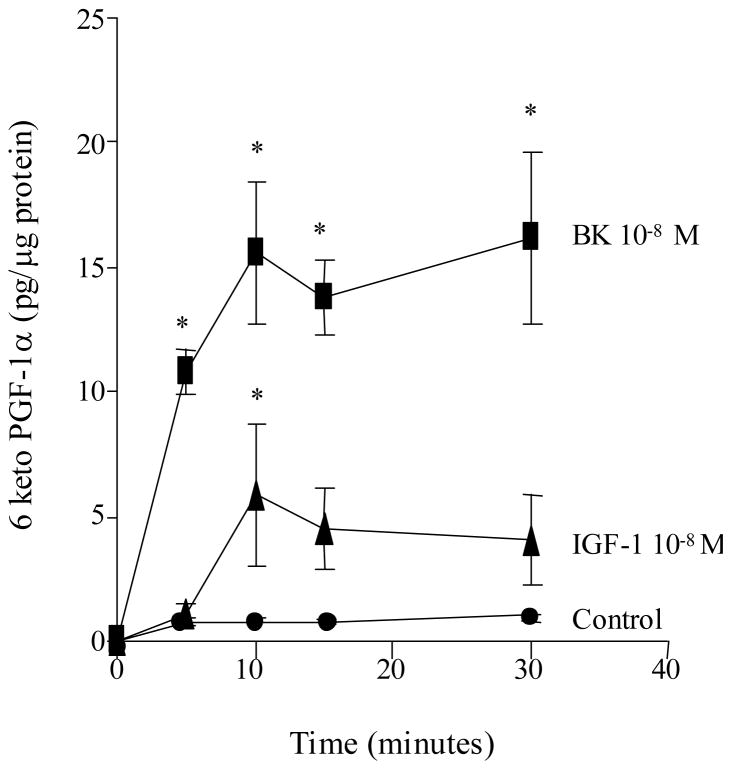

To evaluate the time response through which BK or IGF-1 maximally stimulates the release of 6-keto-PGF1α, VSMC were treated with BK (10−8M) and/or IGF-1 (10−8 M) for various times (0–30 min) as shown in figure 3 (n=6 experiments). The results demonstrate that both BK and IGF-1 increased the synthesis of 6-keto-PGF1α in VSMC within 5 min of addition with a peak effect achieved by 10 min. Basal release of 6-keto-PGF1α did not change throughout the experimental study period. The composite of these findings demonstrate that both BK and IGF-1 promote MAPK activation and stimulate the synthesis of PGI2 in VSMCs.

Figure 3. Time-response effects of BK and IGF-1 on PGI2 (6-keto-PGF1α) release in VSMC.

VSMC were stimulated with either BK (10−8M) or IGF-1 (10−8 M) for various times (0–30 min). Both BK and IGF-1 each produced a significant increase in 6-keto-PGF1α production compared to control values. The peak response was observed 10 min. post stimulation. Figure is representative of 6 separate experiments. *P<0.05 vs. control.

Role of the MAPK pathway in the regulation of 6-keto-PGF1α and cAMP synthesis by BK and IGF-1

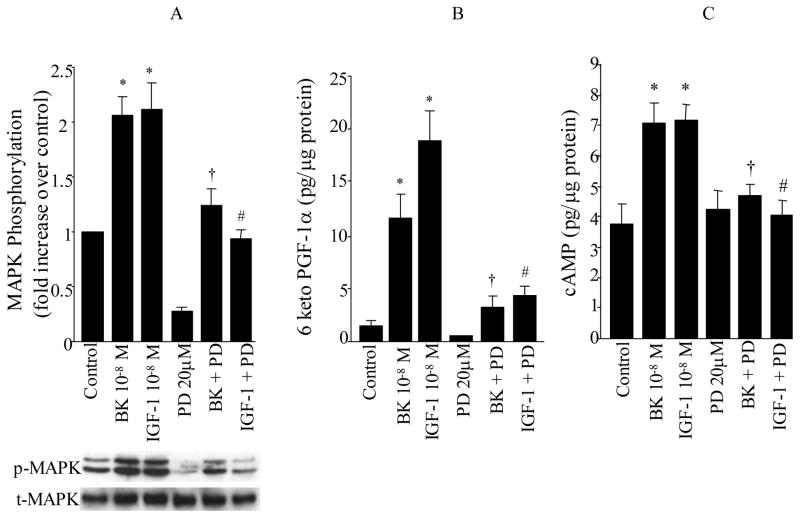

To define the signaling mechanism through which BK and IGF-1 stimulates 6-keto-PGF1α synthesis, the following experiments were carried out to assess the role of the MAPK pathway on this process. It is well established that the ERK family of MAPKs (p42mapk and p44mapk) is rapidly activated in response to growth stimuli and appears to integrate multiple intracellular signals transmitted by various second messengers. To explore the role of MAPK activation on PGI2 and cAMP production by BK and IGF-1 in VSMC, cells were pretreated for 30 min with PD 98059 (20 μM, NEN-Biolabs, Beverly, MA), a specific cell permeable inhibitor of the MAPK activator MEK followed by BK (10−8 M) or IGF-1 (10−8 M) stimulation for 10 min. BK or IGF-1 produced a 2–3 fold increase in ERK phosphorylation compared to unstimulated cells (BK or IGF-1 vs. control, P<0.05, Figure 4A, n=8 experiments). The MEK inhibitor PD98059 decreased basal ERK activity and reduced the level of ERK phosphorylation observed in response to either BK or IGF-1 (BK vs. BK+PD; IGF-1 vs. IGF-1+PD, P<0.05, Figure 4A).

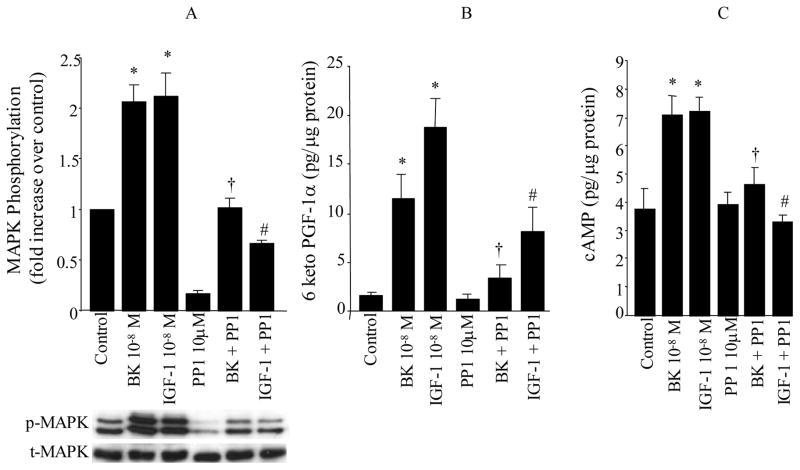

Figure 4. Role of MAPK kinase on MAPK activation (A), the synthesis of PGI2 (6-keto-PGF1α, B) and cAMP (C) by BK and IGF-1.

VSMC were stimulated with either BK (10−8M) or IGF-1 (10−8M) for 10 min in the presence and absence of MEK inhibitor PD98059 (20 μM). MAPK phosphorylation (p42mapk and p44mapk) were measured by immunoblot using anti-phosphotyrosine-MAPK antibodies (p-MAPK) and total MAPK was measured in the same immunoblot by stripping the membrane and re-immunoblotting with anti-total MAPK antibodies (t-MAPK). Release of 6-keto-PGF1α and cAMP into the media, were measured by RIA. Data are expressed as mean±SE and the bar graphs are representative of 6 separate experiments. * P<0.05 vs. control, †P<0.05 vs. BK, #P<0.05 vs. IGF-1.

With regard to 6-keto-PGF1α production, both BK and/or IGF-1 resulted in a 5–8 fold increase in the release of 6-keto-PGF1α compared to unstimulated control VSMC (BK, IGF-1 vs. control, P<0.05, Figure 4B, n=6 experiments). Inhibition of ERK phosphorylation by the MEK inhibitor resulted in a significant decrease in the synthesis of 6-keto-PGF1α in response to either BK or IGF-1 (BK vs. BK+PD; IGF-1 vs. IGF-1+PD, P<0.05, Figure 4B). This suggests that treatment with the MEK inhibitor reduced ERK activity to a level below that necessary to promote PGI2 formation. However, it is also possible that not all of the effects of BK or IGF-1 on prostacyclin production are mediated by MAPK alone. It should be noted that the MEK inhibitor had no significant effect on the basal release of 6-keto-PGF1α by VSMC.

Since activation of PGI2 receptors by PGI2 results in adenylate cyclase activation, which in turn leads to an increase in cAMP synthesis, we examined the effects of PD 98059 on cAMP production in response to either BK or IGF-1. Figure 4C demonstrates that cAMP production is increased 2-fold in VSMC treated with BK and/or IGF-1 compared to untreated cells (BK, IGF-1 vs. control, P<0.05, n=7 experiments). This increase in cAMP production by BK or IGF-1 was completely inhibited by the MEK inhibitor PD 98059 (BK vs. BK+PD: IGF-1 vs. IGF-1+PD, P<0.05, Figure 4C). Inhibition of MEK activity had no significant effect on basal cAMP production but completely inhibited the increase in cAMP levels by BK or IGF-1 (BK vs. BK+PD: IGF-1 vs. IGF-1+PD, P<0.05, Figure 4C). This is consistent with the effect of PD 98059 to significantly blunt BK and IGF-1 stimulation of PGI2 production (Figure 4B).

In the next series of experiments the role of Src family of tyrosine kinases on the regulation of ERK activity, 6-keto-PGF1α and cAMP synthesis was explored. Quiescent VSMC were treated with BK (10−8 M) or IGF-1 (10−8 M) for 10 min. Both BK and IGF-1 resulted in a marked increase in phosphorylation of p44mapk and p42mapk in VSMC compared to unstimulated control cells (Figure 5A, P<0.05, n=8 experiments). To demonstrate a role for Src kinases in ERK activation by BK and IGF-1, VSMC were pretreated for 40 min with a specific cell permeable inhibitor of Src family tyrosine kinases PP1 (10 μM, Biomol Research Laboratories Inc., Plymouth, PA) followed by stimulation with BK (10−8 M) or IGF-1 (10−8 M) for 10 min. Treatment of cells with PP1 lowered basal MAPK activity. However in the presence of PP1 inhibitor, the increase in MAPK phosphorylation achieved in response to BK and IGF-1 was partially reduced (BK vs. BK+PP1; IGF-1 vs. IGF-1+PP1, P<0.05, figure 5A).

Figure 5. Role of Src-kinases on MAPK activation (A), the synthesis of PGI2 (6-keto-PGF1α, B) and cAMP (C) by BK and IGF-1.

VSMC were stimulated with either BK (10−8M) or IGF-1 (10−8M) for 10 min in the presence and absence of Src kinase inhibitor PP1 (10 μM). MAPK phosphorylation (p42mapk and p44mapk) were measured by immunoblot using anti-phosphotyrosine-MAPK antibodies (p-MAPK) and total MAPK was measured in the same immunoblot by stripping the membrane and re-immunoblotting with anti-total MAPK antibodies (t-MAPK). Release of 6-keto-PGF1α and cAMP into the media, were measured by RIA. Data are expressed as mean±SE and the bar graphs are representative of 6–8 separate experiments. * P<0.05 vs. control, †P<0.05 vs. BK, #P<0.05 vs. IGF-1.

Figure 5B, shows the effects of BK and IGF-1 on 6-keto-PGF1α production in the presence and absence of Src kinase inhibitor PP1. Both BK and IGF-1 resulted in a significant increase in the synthesis of 6-keto-PGF1α compared to control cells (BK and IGF-1 vs. Control, P<0.05, n=6 experiments). This increase in synthesis of 6-keto-PGF1α elicited by BK and IGF-1 was significantly decreased by pretreatment of cells with the Src kinase inhibitor PP1 (BK vs. BK+PP1; IGF-1 vs. IGF-1+PP1, P<0.05, Figure 5B), but was higher than cells treated with PP1 alone. Since complete inhibition of PGI2 synthesis in response to BK and IGF-1 stimulation in the presence of PP1 inhibitor was not achieved, it would suggest that other mediators besides src kinases are utilized by BK and IGF-1 to promote synthesis of PGI2.

To determine whether the decrease in 6-keto-PGF1α stimulation following blockade of src kinase would translate into decreased production of cAMP, experiments were conducted to measure the production of cAMP in VSMC treated with either BK (10−8 M) or IGF-1 (10−8M) for 10 min in the presence and absence of the Src kinase inhibitor PP1. The results presented in figure 5C show that BK and IGF-1 produced a 2-fold increase in cAMP production compared to controls (BK, IGF-1 vs. Control, P<0.05, n=6 experiments). However, this increase in cAMP induced by BK and/or IGF-1 was eliminated when VSMC were pretreated with PP1 (BK vs. BK+PP1; IGF-1 vs. IGF-1+PP1, P<0.05, Figure 5C). Inhibition of Src kinases had no significant effect on basal cAMP levels. These studies demonstrate for the first time the requirement for Src kinase activity to stimulate synthesis of PGI2 and cAMP in response to BK and IGF-1 in VSMC. Taken together, the results demonstrate that BK and IGF-1 share common signaling mechanisms to increase the synthesis of PGI2 and cAMP in the VSMC and provide strong support for a role for ERK activation in regulating this process.

Role of PKC in BK and/or IGF-1-induced MAPK phosphorylation and 6-keto-PGF1α

In VSMC activation of phospholipase C by BK leads to production of two second messengers, inositol phosphates and diacylglycerol that induce the release of intracellular calcium and PKC activation (29). We have previously shown that BK leads to PKC activation in VSMC and that PKC is upstream of the MAPK pathway (30). Therefore, in the present study we sought to determine whether inhibition of PKC activity would alter BK-induced production of PGI2 in VSMC. VSMC were pretreated with a PKC inhibitor, bisindolylmaleimide (GFX 109203, 2 μM) for 30 min, followed with BK (10−8 M) stimulation for 10 min. Treatment of VSMC with BK produced a significant increase in 6-keto-PGF1α production compared to unstimulated control cells (25.46±7.16 vs. 4.53±2.02 pg/μg protein, BK vs. Control, respectively, P<0.002, n=6). Pretreatment with the PKC inhibitor GFX did not significantly alter the production of 6-keto-PGF1α in response to BK stimulation (19.22±5.09 vs. 25.46± 7.16 pg/μg protein, BK+GFX vs. BK, respectively, P=0.24, n=6). Another study was carried out to assess the effects of down-regulation of PKC by 24 h of pretreatment with phorbol ester [5μM phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA)] on 6-keto-PGF1α production in response to BK-stimulation. Once again, BK produced a significant increase in 6-keto-PGF1α production compared to control cells (6.78±0.46 vs. 0.22±0.05, BK vs. Control, respectively, P<0.01). However, down-regulation of PKC activity by PMA did not significantly alter the response of BK to stimulate 6-keto-PGF1α synthesis (7.46±1.97 vs. 6.78±0.46, BK+PMA vs. BK, respectively, P=0.42, n=6). Overall, these studies demonstrate that BK stimulates 6-keto-PGF1α synthesis via a PKC-independent pathway.

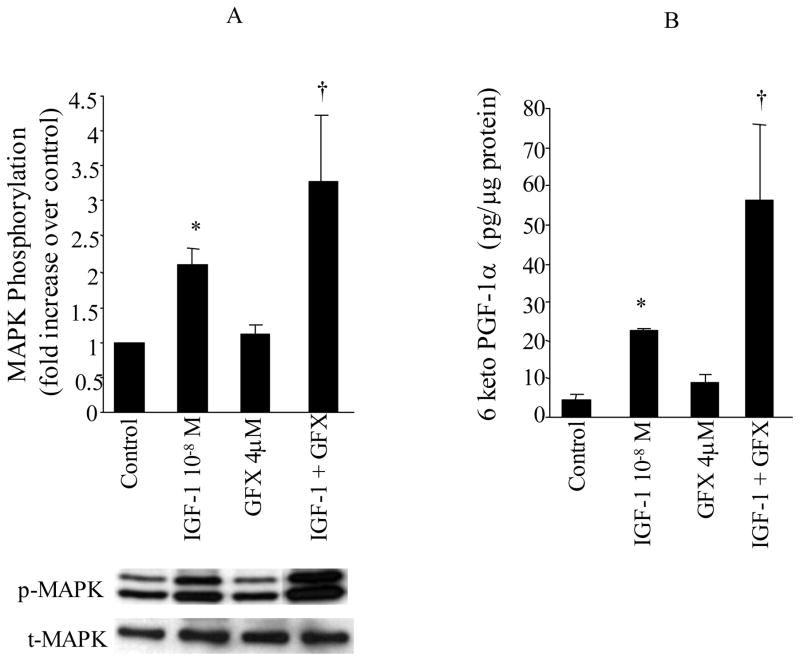

To address whether PKC is essential for IGF-1 to regulate MAPK activity and hence PGI2 synthesis, VSMC were treated with IGF-1 (10−8 M) for 10 min in the presence of a PKC inhibitor, GFX (2 μM). The results shown in Figure 6A demonstrate once again that IGF-1 stimulation results in ERK activation in VSMC (IGF-1 vs. Control, P<0.05, n=5 experiments). Treatment with the PKC inhibitor GFX did not significantly alter basal MAPK phosphorylation, but further increased ERK phosphorylation in response to IGF-1 (IGF-1 vs. IGF-1+GFX, P<0.05, n=5 experiments).

Figure 6. Role of PKC in IGF-1 induced MAPK phosphorylation and PGI2 (6-keto-PGF1α) production.

VSMC were stimulated with either BK IGF-1 (10−8M) for 10 min in the presence and absence of PKC inhibitor bisindolylmaleimide (GFX, 2μM). MAPK phosphorylation (p42mapk and p44mapk) were measured by immunoblot using anti-phosphotyrosine-MAPK antibodies (p-MAPK) and total MAPK was measured in the same immunoblot by stripping the membrane and re-immunoblotting with anti-total MAPK antibodies (t-MAPK). Release of 6-keto-PGF1α into the media, was measured by RIA. Data are expressed as mean±SE and the bar graphs are representative of 5 separate experiments. * P<0.05 vs. control, †P<0.05 vs. IGF-1.

We next examined the effects of PKC inhibition on the production of 6-keto-PGF1α by IGF-1. The results presented in Figure 6B show that IGF-1 produced a significant increase in 6-keto-PGF1α production compared to unstimulated VSMC (IGF-1 vs. Control, P<0.05). The PKC inhibitor did not alter the basal production of 6-keto-PGF1α. However, the production of 6-keto-PGF1α was further increased by IGF-1 when PKC activity was inhibited by GFX (IGF-1 vs. IGF-1+GFX, P<0.05, n=8 experiments, Figure 6B).

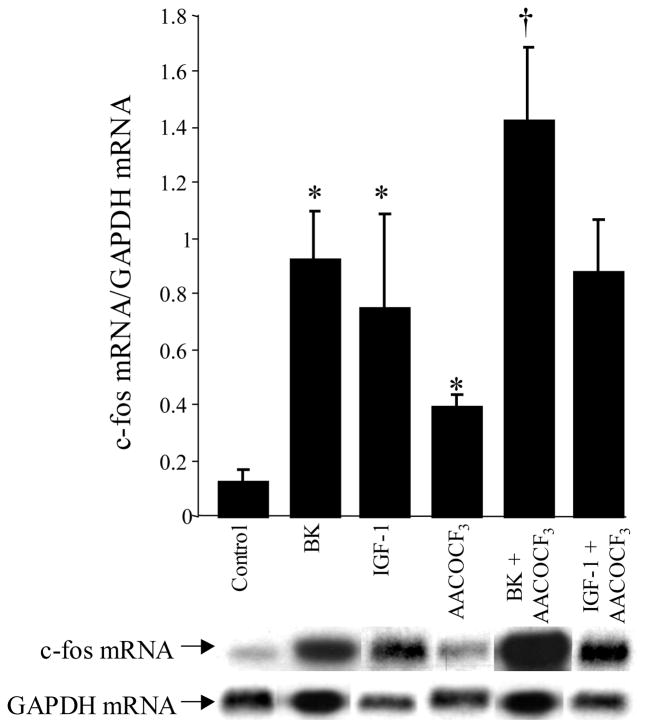

Effect of cPLA2 inhibitor on BK-induced and IGF-1 induced c-fos mRNA expression

Activation of MAPK pathway by either BK or IGF-1 provides a link in the signal transduction pathway from the cytosol to the nucleus. The nuclear targets for MAPK include the activation of transcription factors such as c-fos and the non-nuclear targets include the activation of cPLA2 (31, 32). Once activated, cPLA2 rapidly catalyzes the release of arachidonic acid from the sn-2 position of phospholipids in the plasma membrane leading to synthesis of prostaglandins. We sought to determine whether inhibition of cPLA2 would alter c-fos mRNA expression in response to either BK or IGF-1. VSMC were pretreated with AACOCF3 (20 μM), a cPLA2 inhibitor, followed by BK (10−8 M) or IGF-1 (10−8 M) stimulation for 30 min. The findings demonstrate that BK and IGF-1 treatment produced a 7.5-fold and 6-fold increase in c-fos mRNA/GAPDH mRNA levels compared to untreated cells (0.92±0.17 [n=7] or 0.75±0.34 [n=4] vs. 0.12±0.05 [n=8] c-fos mRNA/GAPDH mRNA; BK or IGF-1 vs. Control, P<0.001, respectively, Figure 7). However, in the presence of the cPLA2 inhibitor, AACOCF3, BK produced a 12-fold increase in the induction of c-fos mRNA levels above control, and a 1.5-fold increase above BK alone (1.42±0.26 [n=4] vs. 0.12±0.05 [n=8] or 0.92±0.17 [n=7] c-fos mRNA/GAPDH mRNA; BK+AACOCF3 vs. control or BK, P<0.01, respectively). With respect to IGF-1, a 7.3-fold increase in c-fos mRNA induction was observed above control, and a 1.2-fold increase was observed above IGF-1 alone (0.88±0.18 [n=5] vs. 0.12±0.05 [n=8] or 0.75±0.34 [n=4] c-fos mRNA/GAPDH mRNA; IGF-1+AACOCF3 vs. control, P<0.01, respectively). Treatment of VSMC with AACOCF3 alone produced a 5.5-fold increase in c-fos mRNA levels compared to control cells (0.66±0.17 vs. 0.12±0.05, AACOCF3 vs. control, p<0.01). GAPDH mRNA level, measured in the same samples was not altered by either BK or IGF-1 treatment.

Figure 7. Role of cPLA2 on IGF-1 and BK-induced c-fos mRNA expression.

VSMC were pretreated with AACOCF3 (20μM), a cPLA2 inhibitor, followed by BK (10−8M) or IGF-1 (10−8M) stimulation for 30 min. c-fos and GADPH mRNA levels were measured by Northern blot analysis. The bar graph represents the relative intensities of c-fos mRNA levels/GADPH mRNA levels. Blot shown is representative of at least 5–7 experiments. *P<0.001 vs. control; †P<0.01 vs. BK.

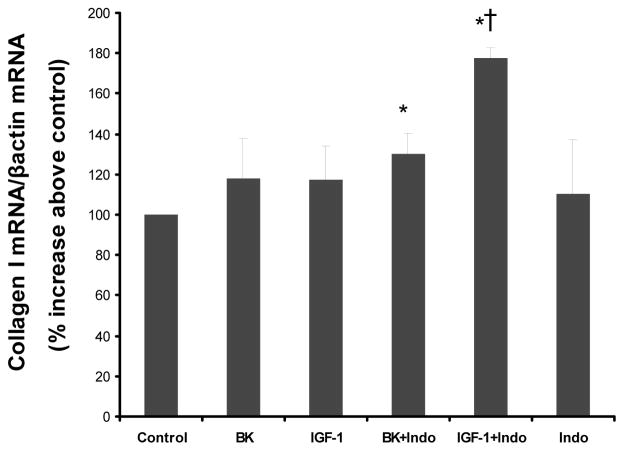

Effect of cPLA2 and cyclooxygenase inhibitors on BK-induced and/or IGF-1 induced collagen I mRNA expression

To further explore the link between cPLA2, BK and IGF-1 on aspects of cellular function, studies were designed to assess whether inhibition of cPLA2 will modulate collagen I mRNA expression in response to either BK or IGF-1 stimulation. VSMC were pretreated with AACOCF3 (20 μM), a cPLA2 inhibitor, followed by BK (10−8 M) or IGF-1 (10−8 M) stimulation for 6h. Collagen I mRNA levels were measured by real-time PCR and expressed relative to β-actin mRNA levels. However, when VSMC were pretreated with AACOCF3, ACOCCF3 alone caused a significant increase in collagen I mRNA levels compared to control, as has been previously shown using other inhibitors of PLA2 activity (13). ACOCCF3 pretreatment resulted in a 303±72 % increase in collagen I mRNA/β-actin mRNA above unstimulated control cells (p<0.003, n=5). This finding confounded our ability to decipher the role of cPLA2 in modulating the expression of collagen I in response to BK or IGF-1 stimulation.

Consequently, in a subsequent study we sought to determine whether blockade of PGI2 generation by inhibition of cyclooxygenase activity, will alter the expression of collagen I mRNA in response to either BK or IGF-1. VSMC were pretreated with indomethacin (20 μM), a cyclooxygenase inhibitor, followed by BK (10−8 M) or IGF-1 (10−8 M) stimulation for 6h. Collagen I mRNA levels were measured by real-time PCR and expressed relative to β-actin mRNA levels. Neither, BK or IGF-1 increased collagen I mRNA levels significantly when used alone. However, both significantly stimulated collagen I expression in cells in which PGI2 generation was inhibited by pretreatment with indomethacin (figure 8). Indomethacin alone did not significantly influence collagen I mRNA levels.

Figure 8. Effect of cyclooxgenase inhibitors on BK-induced and/or IGF-1 induced collagen I mRNA expression.

VSMC were pretreated with Indomethacin (Indo 50μM), a cyclooxygenase inhibitor, followed by BK (10−8M) or IGF-1 (10−8M) stimulation for 6h. Collagen I and β-actin mRNA levels were measured by real-time PCR. The bar graph represents the relative intensities of collagen I mRNA levels/ β-actin mRNA levels. Blot shown is representative of 3 experiments. *P<0.04 vs. control; †P<0.02 vs. IGF-1.

DISCUSSION

Although BK and IGF-1 have been shown to stimulate proliferation of a number of cells including VSMC (7, 20, 33, 34) and mesangial cells (35), the cellular mechanisms through which this regulation occurs is still undefined. BK mediates its effects via activation of the B2-kinin receptor, which is a G-protein-coupled receptor (36) that lacks an intrinsic tyrosine kinase, whereas IGF-1 mediates its effects via activation of a receptor which is a tyrosine kinase receptor (37). The results of the present study demonstrate that activation of BK or IGF-1 receptors in VSMCs generate second messenger signals that can either promote or inhibit growth of the VSMC. Both BK and IGF-1 promoted activation of MAPK, which stimulates the expression of nuclear transcription factors implicated in VSMC growth (11), and each molecule also elicited the synthesis and release of PGI2 which elevates cAMP to inhibit proliferation of the VSMC (7, 9).

The mechanisms involved in MAPK activation are complex and vary with the receptor stimulated and cell type. On binding to the B2 kinin receptor in VSMCs, BK activates phospholipase C via the heterotrimeric GTP binding protein, Gq. Activation of phospholipase C stimulates the production of inositol 1, 4, 5 triphosphate to elevate cytosolic free Ca2+ and generates diacylglycerol, an activator of PKC (29). These second messengers then initiate a complex network of intracellular signaling leading to activation of the extracellular regulated MAPKs, p42mapk and p44mapk (30). In comparison, the IGF-1 receptor is a tyrosine kinase receptor and interaction of the receptor with IGF-1 activates the intracellular kinase domain. This initiates a series of phosphorylation events wherein Shc associates with the adaptor protein Grb2 which promotes the interaction of the guanine nucleotide-releasing protein Sos with Ras (37, 38). Ras activates Raf-1 which phosphorylates MAPK kinase (MEK) leading to the activation of MAPK (39). In the present study pretreatment of VSMCs with PD 98059, an inhibitor of MEK, decreased BK- and IGF-1-induced phosphorylation of p42mapk and p44mapk, indicating a similarity of downstream signaling by the two mitogens. Further, we previously demonstrated a role for the Src family of cytoplasmic tyrosine kinases in BK stimulation of MAPK activity. To determine if Src kinases might similarly contribute to IGF-activation of p42mapk and p44mapk in the VSMC, cells were treated with IGF-1 or BK in the presence of the Src kinase inhibitor, PP1. Inhibition of Src kinases dampened MAPK phosphorylation in response to IGF-1 stimulation. This result suggests that while BK and IGF-1 act through distinctly different types of cellular receptors, the signaling pathways initiated by each molecule become common very early in the cascade of events required for stimulation of MAPK activity in the VSMC.

It is recognized that eicosanoids can modulate the actions of BK and IGF-1 on renal function and vascular tone. However, the cellular mechanisms through which BK and IGF-1 may stimulate eicosanoid production in VSMCs have not been fully addressed. Our data show that both BK and IGF-1 act on the VSMC to produce a concentration- and time-dependent increase in the synthesis and release of PGI2, which is the major cyclooxygenase product synthesized by arterial smooth muscle cells. Increased PGI2 synthesis, in turn, elevated VSMC cAMP levels. A similar action of BK to stimulate PGE2 formation in VSMCs was recently demonstrated in cells cultured from human pulmonary artery (40). PGE2 and the PGI2 analogue, iloprost, also promoted cAMP formation in these cells. Interestingly, prolonged exposure of pulmonary cells to high concentrations of BK led to decreased PGI2-stimulated cAMP production. These findings suggest that excessive and continuous stimulation of prostaglandin formation by VSMCs may desensitize the mechanisms for cAMP regulation.

The cellular mechanisms through which BK and IGF-1 may stimulate eicosanoid production in VSMCs have not been fully addressed. In the present study, stimulation of PGI2 synthesis and cAMP elevation was preceded by a significant increase in p42mapk and p44mapk phosphorylation, and, consequently, experiments were performed to determine if the MAPK signaling pathway might have a role in BK or IGF-1-induced eicosanoid production. Pretreatment of cells with PP1 to inhibit Src kinases, which we have previously shown to be upstream of MAPK, dampened p42mapk and p44mapk phosphorylation observed in response to BK or IGF-1 and decreased BK-or IGF-1-induced PGI2 production to a level below that required to increase cAMP in the VSMC. Moreover, blockade of MAPK phosphorylation by the MEK inhibitor, PD 98058, abolished the increase in PGI2 and cAMP produced by either BK or IGF-1. Taken together, these findings indicate that members of the Src kinase family and p42mapk and p44mapk may have a key role in the regulation of eicosanoid synthesis by BK and IGF-1 in VSMCs.

An interesting difference between BK and IGF-1 actions was observed in VSMCs that were pretreated with GFX, an inhibitor of PKC activation. Inhibition of PKC did not significantly alter BK stimulation of PGI2 synthesis, whereas, inhibition of PKC enhanced IGF-1–stimulated p42mapk and p44mapk phosphorylation and also increased IGF-1 stimulation of PGI2 production. This observation provides further support for a direct link between MAPK activation and PGI2 synthesis in VSMCs and suggests that PKC may be a negative modulator of these responses when initiated through stimulation of the IGF-1 receptor.

Activation of MAPK by BK or IGF-1 provides a link in the transduction of signals from the cytosol to nucleus. The nuclear targets for MAPK include transcription factors such as c-fos which is commonly expressed in response to mitogenic stimuli. Eicosanoids such as PGI2, by stimulating the production of cAMP, have opposing effects and the potential to antagonize mitogen-induced cell proliferation. In the present study, treatment of VSMCs with BK or IGF-1 increased p42mapk and p44mapk phosphorylation and produced a 6-to7-fold induction of c-fos mRNA expression. These effects were accompanied by a concomitant increase in the synthesis and release of PGI2. When cells were pretreated with AACOCF3, an inhibitor of PLA2, to eliminate the production of PGI2, the level of induction of c-fos mRNA was enhanced significantly for BK. A similar trend was observed for IGF-1 but the effect was small and not statistically significant. Such findings suggest that stimulation of PGI2 synthesis in the VSMC serves to counter the proliferative actions of BK and, perhaps, IGF-1 as well. Consistent with this idea is the finding that inhibition of PGI2 synthesis with the cyclooxygenase inhibitor, indomethacin, enhanced the ability of both BK and IGF-1 to stimulate collagen I expression in the VSMC. This result provides additional support for the concept that PGI2 plays a significant role in modulating the proliferative effects of BK and IGF-1 in the arterial vasculature.

In summary, BK and IGF-1 generate second messengers that stimulate early mitogenic and anti-mitogenic signals in VSMCs. While each molecule activates a different type of cellular receptor, similar pathways are utilized for p42mapk and p44mapk activation and for stimulation of PGI2 synthesis. Activation of Src-family of tyrosine kinases appears to be an early event in the signaling cascade wherein the mechanisms of BK and IGF-1 actions become common. BK or IGF-1 induced phosphorylation of p42mapk and p44mapk increases expression of the transcription factor, c-fos, and is also key, to the activation of cPLA2 and increased production of PGI2 by the VSMC. Once formed, PGI2 elevates intracellular cAMP which then serves to modulate the influence of BK and IGF-1 on c-fos expression, as well as the expression of collagen I. These findings indicate that the effect of BK or IGF-1 to stimulate proliferation of VSMCs is an integrated response to the activation of multiple signaling pathways. The excessive cell growth that occurs in certain forms of vascular disease could reflect dysfunction in one or more of these pathways.

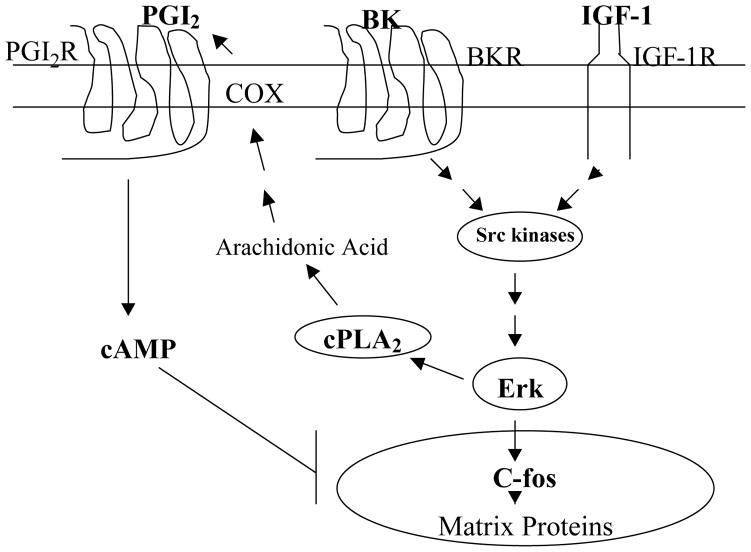

Figure 9. Scheme depicting BK receptor and IGF-1 receptor signaling through MAPK-dependent pathways.

Activation of src-family of tyrosine kinases result in the activation of MAPK which in turn stimulates the activity of cPLA2. Once activated, cPLA2 in turn will activate cyclooxygenases (COX) resulting in the production of inhibitory prostaglandins such as PGI2. PGI2 in turn will lead to elevated cAMP levels, and consequent attenuation of the responses of BK and IGF-1 to stimulate matrix proteins.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grants HL077192 and HL087986 (AAJ) and a grant from the American Heart Association, Mid-Atlantic Affiliate (JGW).

References

- 1.Jackson CL, Schwartz SM. Pharmacology of smooth muscle cell replication. Hypertension. 1992;20:713–736. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.20.6.713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clowes AW, Reidy MA, Clowes MA. Kinetics of cellular proliferation after arterial injury. Lab Invest. 1983;49:327–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ross R. The pathogenesis of atherosclerosis: a perspective for the 1990s. Nature. 1993;362:801–809. doi: 10.1038/362801a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Daeman MJ, Lombardi DM, Bosman FT, Schwartz SM. Angiotensin II induces smooth muscle cell proliferation in the normal and injured rat arterial wall. Circ Res. 1991;68:450–456. doi: 10.1161/01.res.68.2.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rivard A, Andres V. Vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation in the pathogenesis of atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases. Histology & Histopathology. 2000;15(2):557–571. doi: 10.14670/HH-15.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Behrendt D, Ganz P. Endothelial function: from vascular biology to clinical applications. American Journal of Cardiology. 2002;90(10C):40L–48L. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)02963-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fan YY, Ramos KS, Chapman RS. Cell cycle-related inhibition of mouse vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation by prostaglandin E1: relationship between prostaglandin and E1 and intracellular cyclic AMP levels. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 1996;54:101–107. doi: 10.1016/s0952-3278(96)90066-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ignarro LJ, Buga GM, Wei LH, Bauer PM, Wu GY, del Soldato P. Role of the arginine-nitric oxide pathway in the regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98(7):4202–4208. doi: 10.1073/pnas.071054698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takahashi T, Kawahara Y, Okuda M, Yokoyama M. Increasing cyclic AMP antagonizes hypertrophic response to angiotensin II without affecting Ras and MAP kinase activation in vascular smooth muscle cells. FEBS Lett. 1996;397:89–92. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(96)01145-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cobb MH, Goldsmith EJ. How MAP kinases are regulated. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:14843–14846. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.25.14843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robinson MJ, Cobb MH. Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:180–186. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80061-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lille S, Daum G, Clowes MM, Clowes AW. The regulation of p42/p44 mitogen-activated protein kinases in the injured rat carotid artery. J Surg Res. 1997;70:178–186. doi: 10.1006/jsre.1997.5114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Solis-Herruzo JA, Hernandez I, De la Torre P, Garcia I, Sanchez JA, Fernandez I, Castellano G, Munoz-Yague T. G-proteins are involved in the suppression of collagen I gene expression in cultured rat hepatic stellate cells. Cell Signal. 1998;10:173–183. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(97)00036-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nolly H, Carretero OA, Scicli AG. Kallikrein release by vascular tissue. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 1993;265:H1209–H1214. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.265.4.H1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saed G, Carretero OA, MacDonald RJ, Scicli AG. Kallikrein messenger RNA in arteries and veins. Circ Res. 1990;67:510–516. doi: 10.1161/01.res.67.2.510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Oza N, Schwartz JH, Goud DH, Levinsky NG. Rat aortic smooth muscle cells in culture express kallikrein, kininogen and bradykininase activity. J Clin Invest. 1990;85:597–600. doi: 10.1172/JCI114479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Toda N, Bian K, Akiba T, Okamura T. Heterogeneity in mechanisms of bradykinin action in canine isolated blood vessels. Eur J Pharmacol. 1987;135:321–329. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(87)90681-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Briner VA, Tsai P, Schrier RW. Bradykinin: potential for vascular constriction in the presence of endothelial injury. Am J Physiol. 1993;264 (Renal Fluid Electrolyte Physiol 33):F322–F327. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1993.264.2.F322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bornfeldt KE, Arnqvist HJ, Norstedt G. Regulation of insulin-like growth factor-I gene expression by growth factors in cultured vascular smooth muscle cells. J Endocrinol. 1990;125:381–386. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1250381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arnqvist HJ, Bornfeldt KE, Chen Y, Lindstrom T. The insulin-like growth factor system in vascular smooth muscle: interaction with insulin and growth factors. Metab Clin Exp. 1995;44:58–66. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(95)90222-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Delafontaine P, Anwar A, Lou H, Ku L. G-protein coupled and tyrosine kinase receptors–evidence that activation of the insulin-like growth factor I receptor is required for thrombin-induced mitogenesis of rat aortic smooth muscle cells. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:139–145. doi: 10.1172/JCI118381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Delafontaine P. Growth factors and vascular smooth muscle cell growth responses. European Heart Journal. 1998;19 (Suppl G):G19–G22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fath KA, Alexander RW, Delafontaine P. Abdominal coarctation increases insulin-like growth factor I mRNA levels in rat aorta. Circ Res. 1993;72:271–277. doi: 10.1161/01.res.72.2.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang J, Niu W, Nikiforov Y, Naito S, Chernausek S, Witte D, LeRoith D, Strauch A, Fagin JA. Targeted overexpression of IGF-I evokes distinct patterns of organ remodeling in smooth muscle tissue beds of transgenic mice. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:1425–1439. doi: 10.1172/JCI119663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Majack RA, Clowes AW. Inhibition of smooth muscle cell migration by heparin-like glycosaminoglycans. J Cell Physiol. 1994;118:253–256. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041180306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brooker G, Harper JF, Terasaki WL, Moylan RD. Radioimmunoassay of cyclic AMP and cyclic GMP. Adv Cyclic Nucleotide Res. 1979;10:1–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nishimiya T, Daniell HB, Webb JG, Oatis J, Walle T, Gaffney TE, Halsuhka PV. Chronic treatment with propranolol enhances the synthesis of prostaglandins E2 and I2 by the aorta of spontaneously hypertensive rats. J Pharmacol Exp Therap. 1990;253:207–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951;193:265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dixon B, Sharma RM, Dickerson T, Fortune J. Bradykinin and angiotensin II: activation of protein kinase C in arterial smooth muscle. Am J Physiol. 1994;266 (Cell Physiol 35):C1406–C1420. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.266.5.C1406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Velarde V, Ullian ME, Morinelli TA, Mayfield RK, Jaffa AA. Mechanisms of MAPK activation of bradykinin in vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1999;277:C253–C261. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1999.277.2.C253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Borschhaubold AG. Regulation of cytosolic phospholipase A (2) by phosphorylation. Biochemical Society Transactions. 1998;26(3):350–354. doi: 10.1042/bst0260350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Silfani TN, Freeman EJ. Phosphatidylinositide 3-kinase regulates angiotensin II-induced cytosolic phospholipase A2 activity and growth in vascular smooth muscle cells. Archives of Biochemistry & Biophysics. 2002;402(1):84–93. doi: 10.1016/S0003-9861(02)00066-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen Y, Capron L, Magnusson JO, Wallby LA, Arnqvist HJ. Insulin-like growth factor-1 stimulates vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation in rat aorta in vivo. Growth Hormone & IGF Research. 1998;8(4):299–303. doi: 10.1016/s1096-6374(98)80125-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang CM, Chien CS, Ma YH, Hsiao LD, Lin CH, Wu CB. Bradykinin B-2 receptor-mediated proliferation via activation of the Ras/Raf/MEK/MAPK pathway in rat vascular smooth muscle cells. J Biomedical Science. 2003;10(2):208–218. doi: 10.1007/BF02256056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.El-Dahr SS, Dipp S, Yosipiv IV, Baricos WH. Bradykinin stimulates c-fos expression, AP-1 DNA binding activity and proliferation of rat mesangial cells. Kidney Int. 1996;50:1850–1855. doi: 10.1038/ki.1996.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McEachern AE, Shelton ER, Bhakta S, Obernolte R, Bach C, Zuppan P, Fujisaki J, Aldrich RW, Jarnagin K. Expression cloning of rat B2 bradykinin receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:7724–7728. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.17.7724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang XH, Yee D. Tyrosine kinase signaling in breast cancer–Insulin–like growth factors and their receptors in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Research. 2000;2(3):170–175. doi: 10.1186/bcr50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Egan SE, Gidding BW, Brooks MW, Buday L, Sizeland AW, Weinberg RA. Association of Sos Ras exchange protein with grb2 is implicated in tyrosine kinase signal transduction and transformation. Nature. 1993;363:45–51. doi: 10.1038/363045a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seger R, Krebs EG. The MAPK signaling pathway. FASEB J. 1995;9:726–735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.El-Haroun H, Bradbury D, Clayton A, Knox AJ. Interlukin-1 beta, transforming growth factor beta and bradykinin attenuate cyclic AMP production by human pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells in response to prostacyclin analogues and prostaglandin E2 by cyclooxygenase-2 induction and downregulation of adenyly cyclase 1, 2 and 4. Cir Res. 2004;94:353–361. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000111801.48626.F4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]