Abstract

Background

Agrobacterium sp. ATCC31749 is an efficient curdlan producer at low pH and under nitrogen starvation. The helix-turn-helix transcriptional regulatory protein (crdR) essential for curdlan production has been analyzed, but whether crdR directly acts to cause expression of the curdlan biosynthesis operon (crdASC) is uncertain. To elucidate the molecular function of crdR in curdlan biosynthesis, we constructed a crdR knockout mutant along with pBQcrdR and pBQNcrdR vectors with crdR expression driven by a T5 promoter and crdR native promoter, respectively. Also, we constructed a pAG with the green fluorescent protein (GFP) gene driven by a curdlan biosynthetic operon promoter (crdP) to measure the effects of crdR expression on curdlan biosynthesis.

Results

Compared with wild-type (WT) strain biomass production, the biomass of the crdR knockout mutant was not significantly different in either exponential or stationary phases of growth. Mutant cells were non-capsulated and planktonic and produced significantly less curdlan. WT cells were curdlan-capsulated and aggregated in the stationery phase. pBQcrdR transformed to the WT strain had a 38% greater curdlan yield and pBQcrdR and pBQNcrdR transformed to the crdR mutant strain recovered 18% and 105% curdlan titers of the WT ATCC31749 strain, respectively. Consistent with its function of promoting curdlan biosynthesis, curdlan biosynthetic operon promoter (crdP) controlled GFP expression caused the transgenic strain to have higher GFP relative fluorescence in the WT strain, and no color change was observed with low GFP relative fluorescence in the crdR mutant strain as evidenced by fluorescent microscopy and spectrometric assay. q-RT-PCR revealed that crdR expression in the stationary phase was greater than in the exponential phase, and crdR overexpression in the WT strain increased crdA, crdS, and crdC expression. We also confirmed that purified crdR protein can specifically bind to the crd operon promoter region, and we inferred that crdR directly acts to cause expression of the curdlan biosynthesis operon (crdASC).

Conclusions

CrdR is a positive transcriptional regulator of the crd operon for promoting curdlan biosynthesis in ATCC31749. The potential binding region of crdR is located within the −98 bp fragment upstream from the crdA start codon

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12866-015-0356-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: crdR, Curdlan, Agrobacterium, Transcriptional regulator

Background

Microbes can produce diverse extracellular polysaccharides (EPS) for survival in harsh conditions [1]. Curdlan, a water insoluble β-D-1, 3-glucan, can be efficiently produced by Agrobacterium sp. ATCC31749 during stressors of low pH and nitrogen starvation [2-4]. Because of its special gel and immunomodulatory properties, curdlan and its derivatives can be used as food additives and in pharmaceutic products [5-7]. β-D-1,3-glucans can be synthesized by bacteria, fungi [8] and plants [9]; however, large-scale curdlan production occurs mainly via fermentation in Agrobacterium [3,10], Rhizobium strains [11] and Cellulomonas flavigena [12]. An efficient curdlan-producing strain, ATCC31749, whose draft genome sequence is more than 95% homologous to the Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain C58 (ATCC33970) genome, is regarded as a model organism for elucidating curdlan biosynthetic pathways and regulatory mechanisms [13,14]. Using chemical mutant selection, the curdlan biosynthesis operon (crd) was found to contain crdA, crdS, and crdC genes in the ATCC31749 strain [15-17]. Many cultivating conditions including low pH [18], limited nitrogen [19], high dissolved oxygen [20] and adding uracil or cytosine and phosphate salts [21-23] influence curdlan biosynthesis and accumulation. However, how curdlan biosynthesis gene expression is regulated is unclear.

ATCC31750, a mutant strain derived from ATCC31749, had significantly altered intracellular proteins with changes in pH. Specifically, at pH 5.5 (compared to 7.0), key enzymes of curdlan biosynthesis, such as the catalytic subunit of β-1,3-glucan synthase (crdS), UTP-glucose-1-phosphate uridylytransferase (galU), and phosphoglucomutase (pgm) were increased 10, 3, and 17 times, respectively [18]. Intracellular pH changes may activate synthesis of a cellular stringent response signal (p)ppGpp to alter formation of acidocalcisome, which helps maintain intracellular pH and ion homeostasis [24]. To learn how low pH affects curdlan biosynthesis in an ATCC31749 strain, we analyzed genomic sequences of ATCC31749 (access No: AECL01000001–AECL01000095) and that of Sinorhizobium meliloti (access No: NC_003047), which is an acid-tolerant, symbiotic nitrogen-fixing strain [25] using BLAST alignment. We found a transcriptional regulator, PhrR (access No: NC_003047.1 (445435–445854), expression of this gene increased 5–6 times under conditions of low pH (pH 6.2) in S. meliloti [26]. The PhrR gene has a homologous counterpart, AGRO_0435, in ATCC31749. Both PhrR and AGRO_0435 are helix-turn-helix transcriptional factors of the XRE-family, which includes HipB of Escherichia coli (E coli), CH00371 of Rhizobium Leguminosarum (R. Leguminosarum), and PraR of Azorhizobium Caulinodans (A. caulinodans) (Additional file 1) [27-35]. The existence of an essential curdlan production regulatory locus other than the crd operon—locus II—was suggested by Stasinopoulos’s group [15] DNA sequencing confirmed that the locus II gene encodes a helix-turn-helix transcriptional regulatory protein, crdR, and that AGRO_0435 is the crdR gene [26], Unfortunately, whether crdR acts directly to regulate crdASC expression is unclear, so we investigated the role of crdR on crdASC transcriptional activation.

Methods

Bacterial strains and vectors used

Strains and vectors used are listed in Table 1. E. coli strains TG1 and BL21 used for cloning and expression were grown in Luria-Bertani broth (LB). The Agrobacterium sp. ATCC31749 strain was cultivated in LB for growth and for curdlan production, in curdlan-producing medium ([w/v], 5% sucrose, 0.005% yeast extract, 0.5% citric acid, 0.27%K2HPO4, 0.17% KH2PO4, 0.01% MgSO4, 0.37% Na2SO4 2H2O, 0.025% MgCl2 · 6H2O, 0.0024% FeCl3 · 6H2O, 0.0015% CaCl2 · 2H2O, and 0.001% MnCl2 · 4H2O). Culture pH for strain growth was maintained at 7.0 and lowered to 5.5 immediately for curdlan production in a curdlan-producing medium [36]. Primers for PCR amplification designed by DNAMAN software and synthesized by Sangong Biotech (Shanghai, China) are listed in Table 2.

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain/plasmids | Description | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Strains | ||

| E.coli BL21 | Res − Mod − ompT (DE3 with T7 pol) (pLysS with T7 lysozyme;Cm r) Novagen | Lab stock |

| E.coli TG1 | Cloning host | TaKaRa |

| ATCC31749 | Curdlan-producing Agrobacterium sp. (wild-type strain) | ATCC |

| ATCC31749ΔcrdR | ATCC 31749 mutant with gene knockout of crdR | This study |

| Plasmids | ||

| pEGFP | GFP expression vector | Clontech |

| pQE81L | Expression vector, Amp R | Qiagen |

| pBBR122 | Gram-negative broad host vector | MoBiTec |

| pEX18Gm | Expression vector carrying sacBR, Gm R | [36] |

| pBQ | Vector derived from both pQE80 and pBBR122 | [37] |

| pUC19 | Cloning vector | TaKaRa |

| pUC19T-crdR | Suicide vector for crdR knock-out | This study |

| pBQcrdR | Expression vector with T 5 driving crdR expression | This study |

| pBQNcrdR | Expression vector with crdRP driving crdR expression | This study |

| pAG | Expression vector with GFP driven by crd promoter | This study |

| pMD18-T(crdA) | Derivative of pMD18-T with part of crdA | This study |

| pMD18-T(crdS) | Derivative of pMD18-T with part of crdS | This study |

| pMD18-T(crdC) | Derivative of pMD18-T with part of crdC | This study |

| pMD18-T(crdR) | Derivative of pMD18-T with part of crdR | This study |

Table 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primer name | Oligonucleotide | Product length | Product name |

|---|---|---|---|

| crdPG-1 | GTACTCGAGATTGTCGGCAGTCCAG | 607 | crdP |

| crdPG-2 | AGCTCCTCGCCCTTGCTCACCATGAAATCAACTCCTCTGT | ||

| GFP-1 | ACAGAGGAGTTGATTTCATGGTGAGCAAGGGCGAGGAGCT | 746 | GFP |

| GFP-2 | CGCGGATCCTTACTTGTACAGCTCGTCCATG | crdP | |

| crdP-1 | TCACCAACACCAACTCTGGA | ||

| crdP-2 | CATGAAATCAACTCCTCTGT | 607 | crdP |

| crdP142-1 | ATCGTCAGATGCCTATTTGT | 537 | crdP |

| crdP108-1 | AAATTAGTTAATGCAAT | 503 | crdP |

| crdP98-1 | TTAATGCAATTTTTACTATGTT | 493 | crdP |

| crdP53-1 | CCATTTCAATACTGCGGGAGG | 448 | crdP |

| crdP13-1 | AGGAGTTGATTTCATGCTGTT | 408 | crdP |

| crdP1-1 | ATGCTGTTCCGCAATAAG | 395 | crdA |

| crdA395-2 | TCGGTCCGCAGCAGCAAAG | ||

| q-crdA-1 | CAAGGCATAAGCGAAGACATC | 227 | crdA |

| q-crdA-2 | CTCCGTGTTTCAAGTGTGGTC | ||

| q-crdS-1 | AACCTGACGATTGCGATTGGG | 179 | crdS |

| q-crdS-2 | GTGTAGCACCAGAGCGTTTCG | ||

| q-crdC-1 | GTTCGGTCAGGATGCTCAAC | 248 | crdC |

| q-crdC-2 | GCCAAAGTTCGGAATCAATG | ||

| crdR-1 | GCCAGATCTATGACCGAGAATAAGAAAAAGCCT | 437 | crdR |

| crdR-2 | TTGAGCTCTTACTCGGCGTCGCCTTCG | ||

| NcrdR-1 | ACACTCGAGATACACCCGGTCCCTACCAGCATT | crdR | |

| NcrdR-2 | TTTGAGCTCCTTGTCCTTCTTCAGAAGCGTGT | 1302 | crdR |

| q-crdR-1 | TCGGAATGAGCCAGGAGAAGC | 238 | crdR |

| q-crdR-2 | TCAGCCGAGGACAGAAAGTCG | ||

| crdRup-1 | TCTGAGCTCTTCGGCGTTTCGGAATGGTTG | 2533 | CrdR |

| crdRdown-2 | CAACACAAGCTTAACCGTCACCTGGCTCTTGGCA | ||

| crdRcheckGm-2 | TTGGGCATACGGGAAGAAGT | 558 | Gm |

| crdRcheckGm-1 | CGGCTGATGTTGGGAGTAGG | 577 | |

| Rep-Kan-1 | ACGCGTCGACCTTGCCAGCCCGTGGATAT | 3266 | Km |

| Rep-Kan-2 | ACGCGTCGACTCTGTGATGGCTTCCATGTC | ||

| Gm-1 | ATAGTTGTCGAGATATTCACTAGTCGTCAGGTGGCACTTTTCG | 1302 | Gm |

| Gm-2 | CGCGGATCCGCTCTGCTGAAGCCAGTTAC | ||

| celAP1 | ACCCGGTCTATCCCATGA | ||

| celAP-2 | CATCCAGAAACTTTCCGT | 441 | celAP |

| relAP-1 | CCAGATTTCTCAAGGGTC | ||

| RelAP-2 | CATCATGCGATATTCCACA | 443 | relAP |

| crdRP-1 | GCGGCGATCCTAAATGTGAC | ||

| crdRP-2 | CATGCGGTCCTGACACTCG | 466 | crdRP |

| crdSP-1 | TCGGTCGGCACATGGGTCAAT | ||

| crdSP-2 | CATCGCCCTAACCTCGCAGT | 446 | crdSP |

Knockout of the CrdR (AGRO_0435 gene)

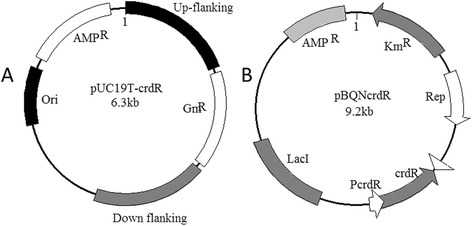

For AGRO_0435 gene knockout, a 2,533 bp fragment of the target gene (AGRO_0435) with up- and down-stream flanking sequences was PCR cloned using primers crdRup-1 and crdRdown-2. The amplified fragment, double digested with both SacI and HindIII, was inserted into the same sites of pUC19 to obtain the pUCcrdR flanking. The gentamicin (Gm) resistance gene expression cassette, obtained by PCR amplification with primers (Gm-1 and Gm-2) from pEX18Gm [37], was double digested with BamHI and SalI and then inserted into the same sites of the pUCcrdR flanking to obtain the suicide knockout vector pUC19T-crdR (Figure 1A). Knockout plasmids were transformed with electroporation using an Eppendorf micropulser. Knockout mutants, selected by screening on LB-agar plates containing 24 μg/mL gentamicin, were confirmed with PCR amplification with 3 pairs of primers including crdR-1 and crdR-2, crdR-1 and crdRcheckGm-2, and crdRcheckGm-1 and crdR-2 (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Maps of pUC19T-crdR (A) and pBQNcrdR (B).

Construction of pBQcrdR and pBQNcrdR for homogenous AGRO_0435 expression

A 437-bp full-length coding region of crdR was amplified with PCR using the primer pairs crdR-1 and crdR-2 (Table 2) with genomic ATCC31749 DNA. The amplified crdR fragment, digested with BamHI and SacI, was ligated into the pBQ vector [38], creating the pBQcrdR vector (Table 1). To construct the vector for crdR expression driven by its native promoter of crdR, an AGRO_0435 fragment with up- and down-stream flanking sequences was PCR cloned using primers NcrdR-1 and NcrdR-2 (Table 2) The obtained 1,302 bp PCR fragment which was double digested with both SacI and XhoI was inserted into SalI and sacI sites of pBQ to create pBQNcrdR (Table 1, Figure 1).

Construction of pAG vector with GFP expression driven by the crd operon promoter

The predicted crd promoter (crdP), which is a 607-bp fragment upstream from the start codon of crdA (ATG), was amplified from genomic ATCC31749 DNA with primers crdAPG-1 and crdAPG-2 (Table 2). The GFP code sequence was amplified with primers GFP-1 and GFP-2 (Table 2) from plasmid pEGFP (Clontech, Mountain View, CA) and the two fragments were fused via PCR amplification. The resultant fused fragment, digested with XhoI and BamHI, was inserted into the same sites of plasmid pQE81L to yield pQEAG. After digestion with SalI, the fragment containing the gram-negative broad host replicating origin and the kanamycin (Kan) resistant gene amplified from pBBR122 (Table 1) with primers pairs Rep-Kan-1 and Rep-Kan-2 (Table 2), was inserted into the XhoI site of pQEAG to yield pAG (Table 1).

Curdlan fermentation and yield analysis

A two-step fermentation protocol was used to measure curdlan yields. In brief, ATCC 31749 and modified strains were inoculated into test tubes containing 5 mL LB and grown overnight at 30°C with 200 revolutions per minute (rpm). About 2 mL each of the seed cultures (SC) were transferred into 500-mL flasks containing 100 mL LB with or without IPTG (final concentration 0.5 mM) at 25°C, 200 rpm for 4 h. Cells were collected by centrifugation (1000 × g for 10 min, 4°C) and cell pellets were added to 125 mL curdlan-producing medium in a 500-mL flask which was shaken at 200 rpm. Every 24 h for 5 days reaction, 15-mL samples were taken from the culture mixture and samples were centrifuged at 8,000 × g for 5 min to collect pellets. Pellets containing both cells and curdlan were resuspended in 15 mL NaOH solution (1 mol/L) for 2 h. Cells pellets were separated by centrifugation at 8,000 × g for 5 min and resulting curdlan was precipitated by the addition of 2.0 mol/L HCl and the pH was adjusted to 6.5. Curdlan was recovered by centrifugation, washed, and dried to a constant weight in an oven (80°C).

crdR, crdA, crdS, and crdC expression analysis using q-RT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted with an EasyPure RNA Kit (TransGen Biotech, Beijing, China), according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The quality and quantity of the extracted RNA was measured using an Ultrospec 2100 spectrophotometer (Amersham Biosciences, Pittsburgh PA, USA) at 260 nm. cDNA synthesis was performed with a PrimerScript RT reagent Kit (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) according to the manufacturer’s instruction by using a 6-bp random primers set. Selected fragments of crdR, crdA, crdS, and crdC, which were amplified with primers qcrdR-1 & qcrdR-2, qcrdA-1 & qcrdA-2, qcrdS-1 & qcrdS-2, and qcrdC-1 & qcrdC-2 (Table 2), were ligated into pMD18-T vectors respectively. Then, using those constructs as standard copies, q-RT-PCR quantification was performed using an Applied Biosystems 7500 fast realtime PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Grand Island, NY ) with SYBR Premix E*TaqII (TaKaRa). All samples were run in triplicate [39].

GFP expression

The constructed vector (pAG) was transformed into both wild-type ATCC31749 and a crdR mutant (ATCC31749ΔcrdR). Transformed bacterial cells were grown in LB for 12 h and curdlan-producing medium for 72 h at 30°C. GFP expression was observed under an optical microscope (Zeiss Observer Berlin, Germany), equipped with epi-fluorescence. Simultaneously, with excitation of 450–490 nm light, Green fluorescence of GFP was measured by a fluorospectrophotometer F97Pro (FProd, Shanghai, China) to collect the data of the emission spectrum and relative fluorescence of cells harvested from both bacterial cell -growing and curdlan-producing phases.

Expression and purification of 6 His-tagged crdR protein

6-His-tagged crdR was expressed in E. coli BL21 through pBQcrdR transformation. The resultant strain grew at 37°C in LB medium (OD600 nm = 0.5–0.6), and crdR protein expression was induced by adding IPTG (final concentration = 0.5 mM). The culture was shaken at 30°C for 4 h at 220 rpm. Cells were harvested by centrifugation were immediately extracted or frozen at −80°C until they were used. 6-His-tagged protein was purified by affinity chromatography using One-Step His-Tagged Protein Miniprep Pack (TIANDZ, Shanghai, China) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Purified crdR dissolved in elution buffer was dialyzed with dialysis buffer (100 mM KAc, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgAc2, 1 mM EDTA, and 1 mM dithiothreitol, 10% glycerol) overnight in a semi-permeable membrane. Protein concentration was measured using an improved Coomassie assay with bovine serum albumin (BSA) as standard.

DNA binding analysis of CrdR by EMSA

DNA fragments containing various lengths of the crd promoter (crdP, crdP142, crdP108, crdP98, crdP53, crdP13, and crdP1) and ~450 bp upstream of the start codon (ATG) of crdR (relA(AGRO_1479) celA (AGRO_4469), and crdS (AGRO_1848) named relAP celAP and crdSP were obtained by PCR amplification with primers listed in Table 2 respectively, those fragments were purified with a DNA gel extraction kit (Sangon Biotech) respectively according to the manufacturer’s protocol. A electrophoretic mobility shift (EMSA) binding assay was performed as previously described with slight modifications [40]. Briefly, 10 μL of 0.25–0.50 mg/mL purified His-tagged crdR in 4× EMSA buffer (15 mM HEPES, 100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 5 mM MgCl2, 10% glycerol, 1 μg/mL poly dI-dC) was incubated with 10 μL of different purified target DNA fragments (0.5 μM) in ddH2O at room temperature for 30 min. DNA-protein complexes were loaded onto a 2% agarose gel and separated at 80 V for 1.5 h, and the gel was stained with SYBR Green I and visualized with a UV trans-illuminator (Upland, CA).

Results

crdR knockout mutant construction and phenotypes

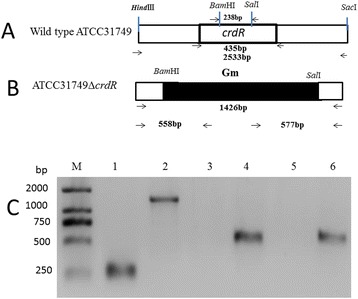

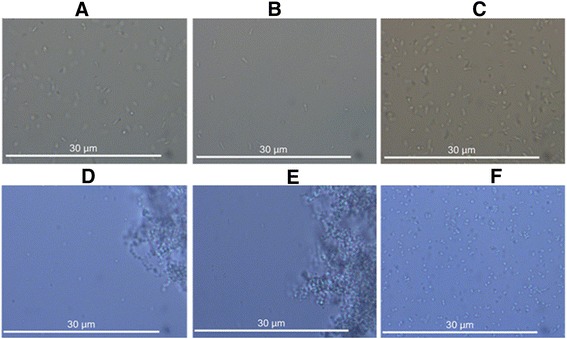

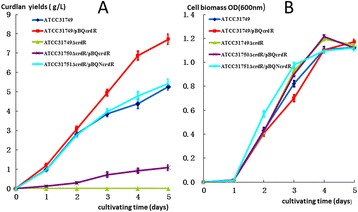

The crdR knockout mutant was constructed via homologous recombination by transformation of the suicide plasmid, pUC19T-crdR (Figure 1A). After strains were selected on gentamicin (Gm) resistant LB plates, knockout mutants were confirmed with PCR amplification (Figure 2). Compared with wild-type (WT) ATCC31749, which is capsulated in the stationary phase, the crdR knockout strain (ATCC31749ΔcrdR) produced less curdlan (Figures 3 and 4) leading to motile and non-capsulated planktonic forms (Figure 3) in both exponential and stationary phases. crdR expression driven by promoters of T5 and native crdR in both ATCC31749 and ATCC31749ΔcrdR strains, respectively, were obtained by transforming the constructs of pBQcrdR and pBQNcrdR (Figure 1). The ATCC31749ΔcrdR/pBQNcrdR strain recovered its curdlan capsulated form of ATCC31749 (Figure 3D and 3E). With a two-step flask-shaking process, curdlan production over 5 days [18,19] in 5 cultivated strains—ATCC31749, ATCC31749/pBQcrdR, ATCC31749ΔcrdR, ATCC31749ΔcrdR/pBQcrdR and ATCC31749ΔcrdR/pBQNcrdR—was compared to assess biomass accumulation and curdlan yields. Data show that (Figure 4B) the biomass of ATCC31749ΔcrdR, ATCC31749/pBQcrdR and ATCC31749ΔcrdR/pBQNcrdR were higher and that ATCC31749ΔcrdR/pBQcrdR had less accumulation than WT ATCC31749 during cultivation days 2 to 4. By the 5th day, however, cell biomasses of all strains were similar. Curdlan yields for ATCC31749, ATCC31749/pBQcrdR, ATCC31749ΔcrdR, ATCC31749ΔcrdR/pBQ-crdR and ATCC31749ΔcrdR/pBQNcrdR were 5.66 g/L, 7.80 g/L, 0.007 g/L, 1.13 g/L, and 5.91 g/L, respectively (Figure 4A). Curdlan yield for the crdR overexpressed strain (ATCC31749/pBQcrdR) was 38% greater than that of WT. crdR controlled by the T5 promoter in ATCC31749ΔcrdR/pBQcrdR could synthesize curdlan, but yields only reached 18% of WT yields; however crdR controlled by its native promoter in ATCC31749ΔcrdR/pBQcrdR recovered curdlan yields of crdR knockout. Low curdlan yields caused by expression of crdR controlled with T5 promoter suggests a more complex regulatory mechanism of crdR expression in the strains. Judged from these data, our observation of crdR is consistent with reports to suggest that crdR is an important regulator of curdlan biosynthesis [15,26].

Figure 2.

Confirmation of the ATCC31749 crdR mutant by PCR amplification. (A, B) crdR was replaced without and with gentamicin resistance gene (Gm) in ATCC31749; (C) PCR amplification. CM: 2Kb DNA ladder, C1, C3, C5: template of genomic DNA of wild-type ATCC31749, while C2, C4, C6: template of genomic DNA of ATCC31749ΔcrdR candidate were used respectively. C2: amplification of the Gm gene; C4: amplification of a fused fragment of the crdR upstream flanking region and the 5’-end of the Gm gene; C6: amplification of the fused fragment of 3’-end of the Gm and the crdR downstream flanking region.

Figure 3.

Effects of crdR on morphological changes. (A, B, C) ATCC31749, ATCC317ΔcrdR/pBQNcrdR and ATCC317ΔcrdR cultivated in growth medium, (D, E, F) ATCC31749, ATCC317ΔcrdR/pBQNcrdR, and ATCC317ΔcrdR cultivated in curdlan-producing medium.

Figure 4.

Changes in curdlan yields (A) and cell biomasses (B) of different strains. Data are means of 3 independent measurements; vertical bars indicate standard errors.

Expression of curdlan biosynthesis genes responding to crdR overexpression

Because crdR is an important regulator of curdlan biosynthesis (Figures 3 and 4), we investigated whether crdR activates expression of crd operon genes. q-RT-PCR analysis was used to evaluate the effects of crdR on crdA, crdS, and crdC (genes of the curdlan biosynthetic operon) mRNA. Stationary phase cells favoring curdlan biosynthesis were compared with exponential phase cells favoring cell growth, and crdR native expression was found to be 29.2 copies/ng total RNA in the stationery phase and 14.0 copies/ng total RNA in the exponential phase in ATCC31749/pBQ. Correspondingly, expression of crdA, crdS, and crdC was at least 10 times greater in the stationary phase compared to the exponential phase (Table 3). mRNA of crdR in ATCC31749/pBQcrdR, induced by 0.5 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) at 30°C for 2 h, was significantly increased compared to that in ATCC31749/pBQ. Corresponding mRNA of crdA, crdS and crdC in ATCC31749/pBQcrdR were more than twice greater when strains were cultivated in both growth and fermentation media. Data confirmed that crdR promotes curdlan production via activating expression of crd operon genes (Table 3).

Table 3.

The expressions of the crd genes quantified by q-RT-PCR*

| ATCC31749/pBQ(E) | ATCC31749/pBQcrdR(E) | ATCC31749/pBQ(S) | ATCC31749/pBQ crdR( S) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| crdA | 0.2373 ± 0.0635 | 1.0944 ± 0.0956 | 244.2038 ± 18.3645 | 923.5690 ± 29.6543 |

| crdS | 0.4050 ± 0.1022 | 2.7739 ± 0.1185 | 86.7645 ± 4.2966 | 176.6229 ± 9.5607 |

| crdC | 0.4972 ± 0.9503 | 2.2787 ± 0.1263 | 4.5239 ± 0.3371 | 14.5744 ± 1.0027 |

| crdR | 14.9112 ± 1.0359 | 654.8556 ± 20.4256 | 29.2068 ± 1.8553 | 193.1226 ± 11.2094 |

*The data are means of three independent determinations, and the unite of value is copies per ng total RNA(copies/ng RNA) E: strain in exponential phase, S:strain in stationary phase.

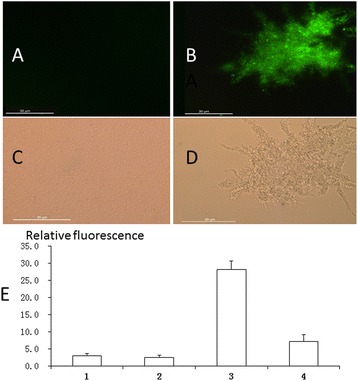

GFP expression controlled by the crd operon promoter (crdP)

To confirm the effect of crdR on crd operon gene expression, a shuttle vector of pAG bearing GFP driven by the crdP was constructed. pAG was transformed into both ATCC31749 and its crdR mutant strain of ATCC31749ΔcrdR. Data indicate that green fluorescence was undetectable by fluorescent microscopy in the crdR mutant strain. In contrast, strong green fluorescence was visible in the WT ATCC31749 strain grown in fermentation media (Figure 5A and 5B). Also, the ATCC31749/pAG strain was curdlan capsulated whereas ATCC31749ΔcrdR/pAG was non-capsulated and motile (Figure 5C and 5D). GFP expression detected by spectrophotometry was consistent with microscopic observations that the relative GFP florescence in ATCC31749/pAG exceeded that in ATCC31749ΔcrdR/pAG at both exponential and stationary phases (Figure 5D). Because the GFP expression pattern represents expression profiles of crdA, crdS and crdC in engineered strains of both ATCC31749/pAG and ATCC31749ΔcrdR/pAG, the effects of crdR expression on GFP expression in those strains indicated that crdR might directly or indirectly interact with the crd operon promoter to regulate expression(s) of curdlan synthetic gene(s). Interestingly relative GFP florescence of exponential phase ATCC31749ΔcrdR/pAG was less than that measured in the stationary phase, suggesting that crdR may synergistically cooperate with other regulators to control crd operon gene expression.

Figure 5.

GFP expressions in constructed strains. (A, B) Stationary phase ATCC31749ΔcrdR/pAG and ATCC31749/pAG observed with fluorescent Microscopy; (C, D) Stationary phase ATCC31749ΔcrdR/pAG and ATCC31749/pAG observed with bright-field microscopy; (E) relative emissive fluorescence of strains activated by light (395 nm); (E1, E2) ATCC31749/pAG and ATCC31749ΔcrdR/pAG at exponential phase; (E3, E4) ATCC31749/pAG and ATCC31749ΔcrdR/pAG at stationary phase. Data are means of 3 independent measurements; vertical bars indicted standard errors.

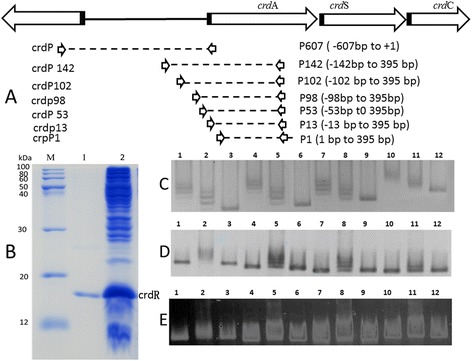

crdR binding with’ different crd operon promoter regions

Bioinformatic analysis of deduced amino acid sequences indicates that crdR has a conserved DNA-binding motif of a helix-turn-helix domain. To confirm that crdR protein can directly interact with the crd operon promoter region, with BSA as a negative protein control, DNA-binding analysis was performed with an electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) with amino terminal 6-His-tagged crdR and DNA fragments containing its putative binding sites. 6 His-tagged crdR protein was expressed and purified into a single band (15 kDa) with SDS-PAGE from E. coli Bl21 which was transformed with pBQcrdR (Figure 6B). The various crdR putative binding fragments, including serial regions of the crd promoter ranging from 607 bp upstream from ATG of crdA fused with or without of 395 bp downstream of ATG of crdA (Figure 6A) and about 450 bp upstream from ATG of crdR, (p) ppGpp synthetase (relA), cellulose synthase catalytic subunit (celA) and curdlan synthase catalytic subunit (crdS), were amplified by PCR with the genomic DNA of ATCC31749 as a template (Figure 6E). Data indicate that 6 His-tagged crdR protein cannot specifically bind 450 bp upstream of ATG of crdR, relA, celA, and crdS, but can bind to different promoter regions of the crd operon (Figure 6C and 6D).To locate crdR binding site(s) on the crd operon promoter, 607 bp upstream from ATG of the crdA sequence which can successfully drive GFP expression in the stationary phase (Figure 5), was chosen and the fragment was shorted to 98 bp upstream from the ATG of crdA to measure binding abilities to crdR. Data indicate that those sequences did not reduce binding to crdR as evidenced by a band shift in EMSA by mixing with or without crdR (Figure 6C). Then, the −98 bp fragments upstream from the crdA start codon was focused for further analysis by continual shortening to 13 bp upstream of ATG of crdA. Using the 395 bp coding sequence of crdA from 1 to 395 bp and BSA as a negative DNA and protein control, respectively, fragment mobility shifts containing −98, −53 and −13 regions of the crd promoter mixed with or without His-tagged crdR were observed and −98, −53 and −13 could all bind to crdR. However the greatest gel mobility shift was observed with the −98 fragment of crdP.

Figure 6.

Binding ability of 6 His-tagged crdR to different DNA fragments. A: Different region of the crdP; B: purification of 6 His-tagged crdR; C, D: Binding ability 6 His-tagged crdR to different regions of crdP; E: Binding of 6 His-tagged crdR, to ~450 bp upstream of ATG at different gene coding regions. BM: protein markers, B1: purified His-tagged crdR, B2: supernatant of pBQcrdR/E. coli Bl21; C1. C4, C7, and C10 are 10 μL of 0.5 μM crdP 98, crdP102, crdP142 and crdP mixed with 10 L of 0.5 mg/mL purified 6 His-tagged crdR protein respectively, C2, C5, C8, and C11 are same as C1. C4, C7, and C10, except 6 His-tagged crdR protein was reduced to 0.25 mg/mL; C3, C8, C9, and C12 are same as C1. C4, C7, and C10, without 6 His-tagged crdR. D1. D4, D7, and D10 are 10 μL of 0.5 μM crdP 98, crdP53, crdP13, and crdP1 only respectively, D2, D5, D8, and D11 are same of .D1. D4, D7, and D10 mixed with 10 μL 0.5 mg/mL 6 His-tagged crdR protein; D3, D8, D9, and D12 are same of .D1, D4, D7, and D10 mixed with 10 μL 0.5 mg/mL BSA respectively, E1, E4, E7, and E10 are crdRP, celAP, and crdSP, E2, E5, E8, and E11 are same of E1, E4, E7, and E10 mixed with 10 μL of 0.25 mg/mL 6 His-tagged crdR protein respectively, E3, E6, E9, and E12 are same of E1, E4, E7, and E10 mixed with 10 μL of 0.5 mg/mL BSA respectively.

Discussion

Here, we report that the crdR, a homolog of PhrR of S. meliloti can activate curdlan synthetic gene expression in Agrobaterium sp. ATCC31749. To our knowledge, ours is the first report to depict molecular functions of the crdR gene. Our data indicate that curdlan yield in an over-expressing crdR strain increased 38% compared to the WT strain. Also, pBQNcrdR transformed to the crdR mutant strain recovered 105% curdlan synthesis of the WT strain (Figure 4). Also, when pAG was transformed into both crdR mutant and WT strains GFP expression controlled by the crd promoter was undetectable by fluorescent microscopy with low relative fluorescence in the crdR mutant. In contrast, the WT strain had visible green color with high relative fluorescence. Finally, q-RT-PCR analysis indicated that crdR is highly expressed in the stationary phase and that overexpression of crdR in the WT strain significantly increased expression of crdA, crdS and crdC. These data agree with previous reports that crdR is key for regulating curdlan biosynthesis. Purified crdR from E. coli BL21 can also specifically bind to the promoter region of crd offering initial evidence that crdR is a positive transcriptional regulator of the crd operon in ATCC31749.

The biomass accumulation in crdR mutant strains was not significantly different from the WT strain, suggesting that the crdR gene is not required for cell growth. Microscopic observation revealed that the crdR mutant was nearly curdlan deficient, resulting in mutant cells with non-capsulated planktonic forms. The WT ATCC31749 strain and the complementary strain of the crdR mutant, ATCC31749ΔcrdR/pBQNcrdR, accumulated curdlan in the stationary phase in culture media with low pH and limited nitrogen, leading to cells were capsulated and aggregated (Figure 3). In addition, expression of crdR was higher in the stationary phase than in the exponential phase, and crdR expression further activated curdlan biosynthesis in the ATCC31749 strain to generate a biofilm. This suggests that curdlan may be critical for biofilm formation in ATCC31749 for improving stress tolerance to harsh conditions.

Bioinformatic analysis indicated that crdR can be grouped into a conserved XRE-family of transcriptional factors that is comprised of HipB in E. coli, PhrR in S. meliloti, CH00371 in R. etli and PraR in A. caulinodans (Additional file 1) [27]. Apparently, diverse stress can induce expressions of XRE-family transcriptional factors. Combining with HipA, HipB, a crdR homologue of E. coli that mediates multidrug stress tolerance can bind to its cis elements with conserved sequences of TATCCN8GGATA (where N8 indicates any 8 nucleotides). Genomic scanning indicated that there is no HipA counterpart in the ATCC31749 strain, and that there were no conservative TATCCN8GGATA sequences in the promoter region of the crd operon. However, crdP does have three distinct hairpin structures located at the −10, −35, and −92 regions (Additional file 2), which are putative crdR binding sites. That purified crdR can bind to an amplified fragment containing the −92 region of crdP more than the −53, and −13 regions indicates that those region are likely the crdR binding site. HipAB is a heterodimer of a transcriptional repressive regulator [28], and crdR may play a different role as a transcriptional activator in the form of a homotetramer or homodimer, which must be confirmed with additional studies. PhrR in S. meliloti was affected by low pH, Cu2 +, Zn2 + and H2O2 stresses [26]. Expression of CH00371 in R. etli was promoted by oxidation and osmotic shock [29,30]; whereas expression of PraR in A. caulinodans was increased by low nitrogen [31]. Primary data from transcriptome analysis obtained from RNAseq indicates that expression of crdR in the curdlan fermenting phase with both low pH and limited nitrogen was twice as great as that in the growing phase of bacterium in LB medium (data not shown) and q-RT-PCR analysis of crdR expression agreed with RNA-Seq data (Table 3). Thus, crdR expression should be triggered by stress factors as well.

Most organisms within the genera of Rhizobium, Azorhizobium, Bradyrhizobium, Mesorhizobium, and Sinorhizobium are symbiotic bacteria to various leguminous plants [32,33]. After bacteria enter plant tissues, their environment changes to low pH (normally 5.5), with limited nitrogen and sufficient carbohydrates [32,33], and this environmental shift affects strain morphology and physiology. To survive with limited nitrogen, genes related to bacterial nitrogen fixing and those for low pH tolerance are expressed. Transcriptional factors such as PhrR and its homologues are instrumental for expression of low pH tolerance genes. Also, with abundant carbohydrates from host photosynthesis, bacterial extracellular polysaccharides (EPS) are synthesized to produce a biofilm [34] to protect the bacteria from stress. Also, the biofilm provides a low-oxygen environment inside the bacteria to support nitrogen fixing reactions. This concept is in agreement with research with PraR from A. caulinodans ORS571, a homolog of crdR, which can mediate stem nodule formation, regulate expression of Reb genes, and increase nitrogen fixation of bacterial strains within stem nodules [31]. Therefore, biosynthesis of curdlan regulated by crdR may originate from ancestral characteristics for survival within a host plant. Currently, detailed regulatory mechanisms of crdR expression, controlled by disadvantageous conditions such as low pH and limited nitrogen remain unknown. However, reports regarding stringent response signal(p)ppGpp, which can induce EPS biosynthesis and bacterial biofilm formation [35] is worthy of study. We hypothesize that crdR expression may be activated by (p)ppGpp, which accumulates under stressful conditions.

Conclusions

In this study, we confirmed that crdR regulates curdlan synthesis by activating expressions of its biosynthetic genes. Ours is the first work to identify XER family transcriptional factor which can activate EPS biosynthesis. crdR may be a multiple-effect regulator controlling expression(s) of the curdlan synthesis gene(s) in ATCC31749 under oxidative stress/low pH and/or limited nitrogen with abundant sugar. This function of curdlan regulation indicates that curdlan biosynthesis of ATCC31749 under harsh conditions may have evolutionary origin.

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by the Chinese Natural Science Foundation (No. 31170057) and the Yunnan Natural Science Foundation (No. 2010CD054).

Additional files

Comparative analysis of crdR homologous protein. Protein sequences of crdR homologous were compared clustalX2 software and PhrR (with 90% similarity to crdR, the same as below) from S. meliloti, CH00371 (86%) from R. leguminosarum, PraR (57%) from A. Caulinodans.

A98 pb promoter sequence of the crd operon ( crdP ) upstream from starting codon of crdA (ATG) with its secondary structure predicted by DNAMAN 98 bp fragment upstream ATG) of the crdA have 3 putative crdR binding sites, which has 3 hairpin structures located in −92, −35, and −10 regions.

Footnotes

Authors’ contributions

XY constructed vectors pAG and pBQ-crdR, analyzed curdlan yield and measured GFP expression, performed q-RT-PCR analysis, crdR purification, and EMSA and drafted the manuscript. CZ constructed vectors of pUC19T-crdR and pBQNcrdR, assisted with crdR knockout and edited the paper. LY assisted with crdR knockout. LZ assisted with statistics and bioinformatic analysis. CL assisted with curdlan yield analysis. ZL assisted with experimental conditions and manuscript editing. ZM conceptualized the study and coordinated the study design as well as assisted with the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Xiaoqin Yu, Email: 14787884558@163.com.

Chao Zhang, Email: zc876827281@sina.com.

Liping Yang, Email: yangmumuxi@sina.cn.

Lamei Zhao, Email: 908039065@qq.com.

Chun Lin, Email: linchun0303@163.com.

Zhengjie Liu, Email: lzj1022@163.com.

Zichao Mao, Email: mao2010zichao@126.com.

References

- 1.Sutherland IW. Microbial polysaccharides from Gram-negative bacteria. Int Dairy J. 2001;11(9):663–674. doi: 10.1016/S0958-6946(01)00112-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harada T, Yoshimura T. Production of a new acidic polysaccharide containing succinic acid by a soil bacterium. Biochim Biophys Acta (BBA) 1964;83(3):374–376. doi: 10.1016/0926-6526(64)90023-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim MK, Lee IY, Ko JH, Rhee YH, Park YH. Higher intracellular levels of uridinemonophosphate under nitrogen-limited conditions enhance metabolic flux of curdlan synthesis in Agrobacterium Species. Biotechnol Bioeng. 1999;62(3):317–323. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0290(19990205)62:3<317::AID-BIT8>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang H, Nishinari K, Williams MA, Foster TJ, Norton IT. A molecular description of the gelation mechanism of curdlan. Int J Biol Macromol. 2002;30(1):7–16. doi: 10.1016/S0141-8130(01)00187-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lehtovaara BC, Gu FX. Pharmacological, structural, and drug delivery properties and applications of 1,3-β-glucans. J Agric Food Chem. 2011;59(13):6813–6828. doi: 10.1021/jf200964u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhan X-B, Lin C-C, Zhang H-T. Recent advances in curdlan biosynthesis, biotechnological production, and applications. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012;93(2):525–531. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3740-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Popescu I, Pelin IM, Butnaru M, Fundueanu G, Suflet DM. Phosphorylated curdlan microgels. Preparation, characterization, and in vitro drug release studies. Carbohydr poly. 2013;94(2):889–898. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reese ET, Mandels M. β-D-1,3 glucanases in fungi. Can J microbiol. 1959;5(2):173–185. doi: 10.1139/m59-022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoffmann G, Timell T. Isolation of a β-1, 3-glucan (laricinan) from compression wood of Larix laricina. Wood Sci Technol. 1970;4(2):159–162. doi: 10.1007/BF00365301. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zheng Z-Y, Lee JW, Zhan XB, Shi Z, Wang L, Zhu L, Wu J-R, Lin CC. Effect of metabolic structures and energy requirements on curdlan production by Alcaligenes faecalis. Biotechnol Biopro Eng. 2007;12(4):359–365. doi: 10.1007/BF02931057. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Footrakul P, Suyanandana P, Amemura A, Harada T. Extracellular polysaccharides of Rhizobium from the Bangkok MIRCEN collection. J Ferment Tech. 1981;59(1):9–14. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kenyon W, Buller C. Structural analysis of the curdlan-like exopolysaccharide produced by Cellulomonas flavigena KU. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol. 2002;29(4):200–203. doi: 10.1038/sj.jim.7000277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goodner B, Hinkle G, Gattung S, Miller N, Blanchard M, Qurollo B, Goldman BS, Cao Y, Askenazi M, Halling C. Genome sequence of the plant pathogen and biotechnology agent Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58. Science. 2001;294(5550):2323–2328. doi: 10.1126/science.1066803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ruffing AM, Castro-Melchor M, Hu W-S, Chen RR. Genome sequence of the curdlan-producing Agrobacterium sp. strain ATCC 31749. J bacteriol. 2011;193(16):4294–4295. doi: 10.1128/JB.05302-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stasinopoulos SJ, Fisher PR, Stone BA, Stanisich VA. Detection of two loci involved in (1→ 3)-β-glucan (curdlan) biosynthesis by Agrobacterium sp. ATCC31749, and comparative sequence analysis of the putative curdlan synthase gene. Glycobiology. 1999;9(1):31–41. doi: 10.1093/glycob/9.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karnezis T, Epa VC, Stone BA, Stanisich VA. Topological characterization of an inner membrane (1→ 3)-β-D-glucan (curdlan) synthase from Agrobacterium sp. strain ATCC31749. Glycobiology. 2003;13(10):693–706. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwg093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hrmova M, Stone BA, Fincher GB. High-yield production, refolding and a molecular modelling of the catalytic module of (1, 3)-β-d-glucan (curdlan) synthase from Agrobacterium sp. Glycoconj J. 2010;27(4):461–476. doi: 10.1007/s10719-010-9291-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jin L-H, Um H-J, Yin C-J, Kim Y-H, Lee J-H. Proteomic analysis of curdlan-producing Agrobacterium sp. in response to pH downshift. J Biotechnol. 2008;138(3):80–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang L. Effect of nitrogen source on curdlan production by Alcaligenes faecalis ATCC 31749. Int J Biol Macromol. 2013;21(2):218–220. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2012.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang H-T, Zhan X-B, Zheng Z-Y, Wu J-R, English N, Yu X-B, Lin C-C. Improved curdlan fermentation process based on optimization of dissolved oxygen combined with pH control and metabolic characterization of Agrobacterium sp. ATCC 31749. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012;93(1):367–379. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3448-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.J-h L, Lee IY. Optimization of uracil addition for curdlan (β-1 → 3-glucan) production by Agrobacterium sp. Biotechnol Lett. 2001;23(14):1131–1134. doi: 10.1023/A:1010516001444. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu L, Wu J, Liu J, Zhan X, Zheng Z, Lin CC. Enhanced curdlan production in Agrobacterium sp. ATCC 31749 by addition of low-polyphosphates. Biotechnol Biopro Eng. 2011;16(1):34–41. doi: 10.1007/s12257-010-0145-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.West T-P. Pyrimidine base supplementation effects curdlan production in Agrobacterium sp. ATCC31749. J Basic Microbiol. 2006;46(2):153–157. doi: 10.1002/jobm.200510067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ruffing AM, Chen RR. Transcriptome profiling of a curdlan-producing Agrobacterium reveals conserved regulatory mechanisms of exopolysaccharide biosynthesis. Microb Cell Fact. 2012;11(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-11-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Galibert F, Finan TM, Long SR, Pühler A, Abola P, Ampe F, Barloy-Hubler F, Barnett MJ, Becker A, Boistard P. The composite genome of the legume symbiont Sinorhizobium meliloti. Science. 2001;293(5530):668–672. doi: 10.1126/science.1060966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reeve WG, Tiwari RP, Wong CM, Dilworth MJ, Glenn AR. The transcriptional regulator gene phrR in Sinorhizobium meliloti WSM419 is regulated by low pH and other stresses. Microbiology. 1998;144(12):3335–3342. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-12-3335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lin C-Y, Awano N, Masuda H, Park J-H, Inouye M. Transcriptional repressor HipB regulates the multiple promoters in Escherichia coli. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;23(6):440–447. doi: 10.1159/000354311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schumacher MA, Piro KM, Xu W, Hansen S, Lewis K, Brennan RG. Molecular mechanisms of HipA-mediated multidrug tolerance and its neutralization by HipB. Science. 2009;323(5912):396–401. doi: 10.1126/science.1163806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vercruysse M, Fauvart M, Jans A, Beullens S, Braeken K, Cloots L, Engelen K, Marchal K, Michiels J. Stress response regulators identified through genome-wide transcriptome analysis of the (p) ppGpp-dependent response in Rhizobium etli. Genome Biol. 2011;12(2):R17. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-2-r17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martínez-Salazar JM, Salazar E, Encarnación S, Ramírez-Romero MA, Rivera J. Role of the extracytoplasmic function sigma factor RpoE4 in oxidative and osmotic stress responses in Rhizobium etli. J Bacteriol. 2009;191(13):4122–4132. doi: 10.1128/JB.01626-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Akiba N, Aono T, Toyazaki H, Sato S, Oyaizu H. phrR-like gene praR of Azorhizobium caulinodans ORS571 is essential for symbiosis with Sesbania rostrata and is involved in expression of reb genes. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76(11):3475–3485. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00238-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raven J, Smith F. Nitrogen assimilation and transport in vascular land plants in relation to intracellular pH regulation. New Phytologist. 1976;76(3):415–431. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.1976.tb01477.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith FA, Raven JA. Intracellular pH and its regulation. Annu Rev Plant Physiol. 1979;30(1):289–311. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pp.30.060179.001445. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Flemming H-C, Neu TR, Wozniak DJ. The EPS matrix: the “house of biofilm cells”. J Bacteriol. 2007;189(22):7945–7947. doi: 10.1128/JB.00858-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Potrykus K, Cashel M. (p) ppGpp: Still magical? Annu Rev Microbiol. 2008;62:35–51. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.62.081307.162903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yu L, Wu J, Zheng Z, Lin C, Zhan X. Changes in gene transcription and protein expression involved in the response of Agrobacterium sp. ATCC 31749 to nitrogen availability during curdlan production. Prikl Biokhim Mikrobiol. 2011;47(5):537–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hoang TT, Karkhoff-Schweizer RR, Kutchma AJ, Schweizer HP. A broad-host-range Flp-FRT recombination system for site-specific excision of chromosomally-located DNA sequences: application for isolation of unmarked Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutants. Gene. 1998;212(1):77–86. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(98)00130-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mao Z, Chen RR. Recombinant synthesis of hyaluronan by Agrobacterium sp. Biotechnol Prog. 2007;23(5):1038–1042. doi: 10.1021/bp070113n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Toyoda K, Teramoto H, Inui M, Yukawa H. Expression of the gapA gene encoding glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase of Corynebacterium glutamicum is regulated by the global regulator SugR. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2008;81(2):291–301. doi: 10.1007/s00253-008-1682-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parés-Matos EI. Electrophoretic mobility-shift and super-shift assays for studies and characterization of protein-DNA complexes. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;977:159–67. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-284-1_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]