Abstract

Aims

Obesity and insulin resistance are associated with increased oxidant stress. However, treatments of obese subjects with different types of antioxidants often give mixed outcomes. In this work, we sought to determine if long-term supplementation of a thiol antioxidant, β-mercaptoethanol, to diet-induced obese mice may improve their health conditions.

Main Methods

Middle-age mice with pre-existing diet-induced obesity were provided with low concentration β-mercaptoethanol (BME) in drinking water for six months. Animals were assessed for body composition, gripping strength, spontaneous physical and metabolic activities, as well as insulin and pyruvate tolerance tests. Markers of inflammation were assessed in plasma, fat tissue, and liver.

Key findings

BME-treated mice gained less fat mass and more lean mass than the control animals. They also showed increased nocturnal locomotion and respiration, as well as greater gripping strength. BME reduced plasma lipid peroxidation, decreased abdominal fat tissue inflammation, reduced fat infiltration into muscle and liver, and reduced liver and plasma C-reactive protein. However, BME was found to desensitize insulin signaling in vivo, an effect also confirmed by in vitro experiments.

Conclusion

Long-term supplementation of low dose thiol antioxidant BME improved functional outcomes in animals with pre-existing obesity. Additional studies are needed to address the treatment impact on insulin sensitivity if a therapeutic value is to be explored.

Keywords: thiol antioxidant, diet-induced obesity, inflammation, insulin resistance, gripping strength, spontaneous locomotion, respiration, oxidant stress

Introduction

Obesity is often associated with increased fat tissue oxidative stress and inflammation 1. Increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in obesity is considered an adverse cellular response to nutrient excess, which shifts the cellular and systemic redox to a more oxidized state. This has been proposed as a core mechanism connecting overfeeding to insulin resistance and metabolic disorders 2, 3. Diverse pharmacologic and genetic approaches to decrease ROS have been shown to reduce obesity and improve insulin reactivity 4–6, although studies on the effect of dietary antioxidants remain inconclusive 7–9. Among the vast literature about the therapeutic effect of antioxidant supplements on obesity, few have addressed the fact that hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), a mild ROS by itself but a precursor for several strongly damaging radicals, is also an important physiological messenger for insulin signaling 10–13. As a matter of fact, H2O2 is essential for insulin-mediated metabolic effects in adipocytes, including stimulation of glucose transport and lipid synthesis, as well as suppression of lipolysis 14–16. Even a proper concentration of exogenous H2O2 alone can act as an insulin mimetic to facilitate these metabolic effects 16, 17.

In most cases, exogenously provided antioxidants are non-specific ROS scavengers. Therefore, in principle, antioxidants can alleviate ROS-induced inflammation and insulin resistance but also may paradoxically intercept the normal insulin signaling pathway. For instance, a recent clinical study reported that supplementation of a thiol antioxidant, N-acetylcysteine (NAC), reduces fat mass but simultaneously raises insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) in obese non-diabetic subjects 18. While this observation is well in line with the literature that ROS scavengers can blunt insulin signaling, even the authors considered the outcome “disappointing”. Instead of further investigation on functional outcomes, such as weight-loss associated changes of inflammation and physical or metabolic function, the authors went on to identify an adjunct supplement to “correct” the negative impact of NAC so that a combined treatment would reduce fat mass without raising insulin resistance 18. To our knowledge, while most studies consider a simultaneous reduction of fat mass and insulin resistance as two inseparable markers for a successful intervention, few have objectively examined the functional health outcomes when the two markers move in different directions. Besides, both clinical and preclinical studies often focused on how antioxidant supplements affect plasma and tissue markers of obesity, insulin resistance, and inflammation, with a general paucity in functional assessments.

In this work, we tried to bridge the molecular and functional impacts of thiol antioxidants on obesity and its related metabolic disorders. To better mimic the metabolic conditions and treatment responses in obese humans, we used middle-age diet-induced obese mice, insulin resistant but not diabetic, as our preclinical model. We used β-mercaptoethanol (BME) as the antioxidant for this long-term study. BME is a cost-effective small thiol with relatively high aqueous stability. Although known for its unpleasant odor at extremely high concentration, low dose BME is mild and well tolerated but under-appreciated as a potential food additive. Several laboratories have reported long-term health benefits of BME in preclinical models, including brain chemistry, longevity, weight control, tumor suppression, and immunological functions19–25. We hypothesized that long-term treatment with low dose BME would reduce systemic oxidative stress and improve general health in animals with pre-existing obesity and insulin resistance.

Materials and Methods

Animals

This study was approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Boston University School of Medicine. Male C57BL/6 mice (6 mo) were purchased from Jackson Laboratories. These mice were placed on a high fat diet early in life and already obese and insulin resistant upon arrival. Animals were placed on a high fat diet (Research Diets, 12451) throughout this study and regularly monitored for body composition by Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR). After acclimation for one month, animals were divided into control and BME groups with matched body composition (control: 39.8 ± 1.34 g, 26.3 ± 2.5% fat, BME: 40.8 ± 0.92 g, 26.4 ± 1.8% fat, n = 16 per group).

BME (Sigma-Aldrich, #M6250) was diluted in distilled water to 2.5 mM before each water change, twice per week. There was no significant difference in water intake between the control and BME-treated animals (about 3 ml/day/mouse), as previously reported 19. The calculated daily BME intake was about 200 nmol/g, similar to that used in “nutritional” studies 19 but an order of magnitude lower than the empirically determined LD50 in mice (4.42 μmol/g)26. To probe the ambient chemical stability of aqueous BME, we used NMR to measure the proton spectrum of a 2.5 mM BME solution on different days after the solution was placed at room temperature and calculated the amount of product that remained intact over time. The amount of BME remained intact was 85–87% and 73–75% on day-3 and day-6, respectively. By refreshing the solution twice a week, BME concentration in the drinking water remained between 2.0–2.5 mM. Animals were kept in 12h/12h light-dark with free access to food and water. Food intake was measured daily for two weeks in the second month of treatment and was found to be similar between the two groups (7.29 ± 0.22% and 7.92 ± 0.4% of body weight, for control and BME-treated, respectively, p = 0.2), as would be expected based on the literature 20.

Functional assessments

The effect of BME supplementation on body composition was monitored monthly by NMR. Gripping strength was measured in the 4th and 6th month, using an automatic force transducer (Columbus Instruments). Spontaneous physical and metabolic activities were recorded in the 5th month, using the Oxymax420 system (Columbus Instruments). Technical details for these measurements have been described previously 27.

Tests for insulin tolerance and pyruvate tolerance

For the insulin tolerance test, food was removed from 8 am to 12 pm. Mice were then injected with insulin (0.75 U/kg diluted in saline, i.p). For pyruvate tolerance test, mice were fasted overnight and then injected with sodium pyruvate (2 g/kg, Gibco #11360-070, i.p). For both tests, blood glucose concentrations were measured before injection and every 15 min for up to 120 min post-injection.

Plasma and tissue analysis

Food was removed in the morning, about two hours before animal sacrifice. Blood was collected for analysis for lipids, glucose, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and multiple cytokines, using a core facility (www.med.unc.edu/anclinic). Total lipid peroxidation, antioxidant capacity, and adiponectin concentration were measured using commercial kits (ZeptoMetrix # 0801192, BioVision #K274-100; Alpco #47-ADPMS-E01). Plasma total and reduced glutathione were measured using a kit from Millipore (#371757).

Formalin-fixed fat tissue was processed for hematoxylin and eosin staining at the Rodent Histopathology Core (http://www.dfhcc.harvard.edu/core-facilities/rodent-histopathology-pathology). The histology results of all specimens were analyzed by the Image J program. The leftover fat for the epididymal depot was pulverized in liquid nitrogen and well mixed before sampling for RNA and protein analysis. RNA isolation and real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) were performed as described previously 28. The PCR primer sequences are listed in Table 1. Protein lysates were prepared by homogenization in a cell lysis buffer (Cell Signaling, #9803) supplemented with 0.1% SDS and inhibitors of proteases and phosphatases. Western analysis was performed following standard protocols with antibodies from Cell Signaling (phospho-p65Ser536 #3033; phospho-p50Ser993, #4806; phospho-AktSer473#4060, and phospho-AktTh308 #2965, and Akt #4691, phospho-S6Ser235/236, #2211, and phospho-4EBP1Th37/46, #9459) or Santa Cruz (GADD153, sc-7351; GRP78, sc-1051; GAPDH, sc-48167; NFκB-P65, sc-8008; and NFκB-p50, sc-114).

Table 1.

Primer sequences for real-time PCR

| Target gene | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|

| TNFα - NM_013693.2 | 5′- tgcctatgtctcagcctcttc -3′ | 5′- gaggccatttgggaacttct -3′ |

| IL6 - NM_031168.1 | 5′- gctaccaaactggatataatcagga -3′ | 5′- ccaggtagctatggtactccagaa -3′ |

| IFNγ - NM_008337 | 5′- agcaaggcgaaaaaggatgc -3′ | 5′- tcattgaatgcttggcgctg -3′ |

| CRP - X13588.1 | 5′- ctcccagtggtctgacgttt -3′ | 5′- ggggctgaaccactttgtaa -3′ |

| iNOS - M87039.1 | 5′- ctttgccacggacgagac -3′ | 5′- tcattgtactctgagggctgac -3′ |

| UCP1 - NM_009463 | 5′- ggcctctacgactcagtcca -3′ | 5′- taagccggctgagatcttgt -3′ |

| UCP2 - NM_011671 | 5′- acagccttctgcactcctg -3′ | 5′- ggctgggagacgaaacact -3′ |

| UCP3 - NM_009464.3 | 5′- tacccaaccttggctagacg -3′ | 5′- gtccgaggagagagcttgc -3′ |

| FAS - NM_007988 | 5′- gctgctgttggaagtcagc -3′ | 5′- agtgttcgttcctcggagtg -3′ |

| SCD1- NM_009127 | 5′- ttccctcctgcaagctctac -3′ | 5′- cagagcgctggtcatgtagt -3′ |

| Glut4 - NM_009204.2 | 5′- gacggacactccatctgttg -3′ | 5′- gccacgatggagacatagc -3′ |

TNFα - Tumor necrosis factor-alpha, IL6 - interleukin 6, INFγ - interferon gamma, CRP - C-reactive protein, iNOS – inducible Nitric oxide synthase, UCP1 - uncoupling protein 1, UCP2 - uncoupling protein 2, UCP3 - uncoupling protein 3, FAS - Fatty acid synthase, SCD1- stearoyl-Coenzyme A desaturase 1, Glut4 - Glocuse transporter 4

Cell culture and Western analysis

HepG2 cells were originally purchased from ATCC and grown in DMEM containing normal glucose concentration (5.5 mM) and 10% fetal bovine serum plus standard antibiotics. Upon confluence, cells were washed and incubated in serum-free medium overnight. BME was added to the cell culture the next morning. Insulin was added 30 minutes after BME. Cells were harvested 30 min after incubation with insulin and used for Western analysis following standard protocol. Twenty five microgram total protein was loaded to each lane.

Statistics

All data were presented as means ± standard error. Comparisons between control and BME-treated groups were conducted using Student’s t test.

Results

Effect of BME supplementation on plasma parameters

As a thiol donor, BME is expected to act as a ROS scavenger within its immediate environment. Plasma accumulation of thiobarbiturate reactive substances (TBARS) is a marker of lipid peroxidation and generally reflects the antioxidant capacity. As expected, plasma TBARS was found to be lower in BME-treated mice than control (Table 2). There was also a trend for increased total antioxidant capacity in BME-treated mice (Table 2). The relatively small magnitude of these changes may be reflective of low intake and/or rapid in vivo turnover of the antioxidant. Possibly for this reason also, we found no significant difference in plasma total and reduced glutathione levels between the control and treated groups (Table 2).

Table 2.

The effect of BME on plasma parameters (t test, n = 10–16 per group).

| Target | TBAR μM | TAC mM | GSH μM | GSSG μM | TAG mg/dL | Cholesterol mg/dL | Glucose mg/dl | AST mU/ml | ALT mU/ml |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 119.5 ± 5 | 3.1 ± 0.1 | 22.9 ± 0.9 | 8.0 ± 0.5 | 73 ± 7 | 296 ± 19 | 367± 15 | 132 ± 37 | 1055 ± 275 |

| BME | 101 ± 4 | 3.4 ± 0.2 | 23.7 ±1.3 | 8.8 ± 0.6 | 77 ± 4 | 292 ± 17 | 377 ± 14 | 139 ± 24 | 889 ± 153 |

| p value | 0.01 | 0.17 | 0.53 | 0.32 | 0.6 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.6 |

Total plasma triglycerides, cholesterol, and glucose were not affected by BME supplementation (Table 2). Circulating AST and ALT in these mice were relatively high, but no difference was observed between the two groups (Table 2). These results are in agreement with prior reports that chronic high fat feeding raises AST and ALT activity 29, but also indicate that supplementation of BME at this dosage and time course did not cause liver toxicity under the current experimental conditions.

Effect of BME supplementation on fat mass, plasma adipokines, muscle mass and gripping strength

Animals of both groups continued to gain weight over time, but the BME-treated animals consistently gained less than the control (Figure 1A). After six months, BME-treated mice displayed significantly smaller fat pad sizes in both abdominal (epididymal and perirenal) and subcutaneous (inguinal) depots than the control (Figure 1B). Plasma concentration of leptin, a sensitive marker positively associated with whole body fat mass 30, was also lower in BME-treated mice (Table 3). In contrast, plasma concentration of total adiponectin, known to be inversely related to obesity 31, 32, was higher in BME-treated mice (Table 3). However, the high molecular weight (HMW) adiponectin, known for its insulin sensitizing effect 32, was not different between the two groups (Table 3). Since adiponectin assembly into the HMW form involves disulfide bonds and is redox sensitive 33, 34, the presence of BME may have interfered with the assembly and maintenance of adiponectin in its HMW form.

Figure 1. Effect of BME on body composition, muscle mass and gripping strength.

(A) Time dependent weight gain and fat mass increment (■ for control, ▲ for BME, means ± se, n = 16). (B) Terminal weight of different fat depots. (C) Gripping strength measured at the 4thand 6th month after BME supplementation, and (D) Terminal weight of skeletal muscle groups (C: control, B: BME-treated, Epi: epididymal, Per: perirenal, Ingu: inguinal; means ± se, n = 16, t test for two group comparison and one-way ANOVA/post-hoc Tukey’s test for multigroup comparison).

Table 3.

The effect of BME on plasma adipokines (t test, n = 16 per group)

| Target | Leptin, ng/ml | Total Adiponectin, ng/ml | HMW Adiponectin, ng/ml |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 31.6 ± 1.5 | 1.60 ± 0.08 | 1.01 ± 0.07 |

| BME | 27.2 ± 0.7 | 1.92 ± 0.07 | 0.97 ±0.06 |

| p value | 0.01 | 0.001 | 0.9 |

Concurrent with their lower fat pad sizes, the BME-treated mice displayed modestly but significantly increased skeletal muscle mass (Figure 1D). To test whether the difference in body composition might reflect a change in physical strength, we measured the gripping strength in the 4th and the 6th month. As shown in Figure 1C, at both time points, BME-treated mice displayed greater gripping strength. Since no measurement was performed at baseline, we cannot comment on the apparent difference detected in the 4th month. However, results in Figure 1C clearly indicate a significant decline in gripping strength of the control mice from the 4th to the 6th month, while no such decline was detected in the BME-treated mice. Since normal middle-age mice do not lose gripping strength over a two month period (data not shown) and the control mice did not lose lean mass within the observation time frame (NMR, data not shown), our results suggest that the control mice were losing gripping strength because of muscle weakness or cognitive decline due to the high fat diet 35, whereas co-treatment with BME might have blunted either effect as previous suggested 23.

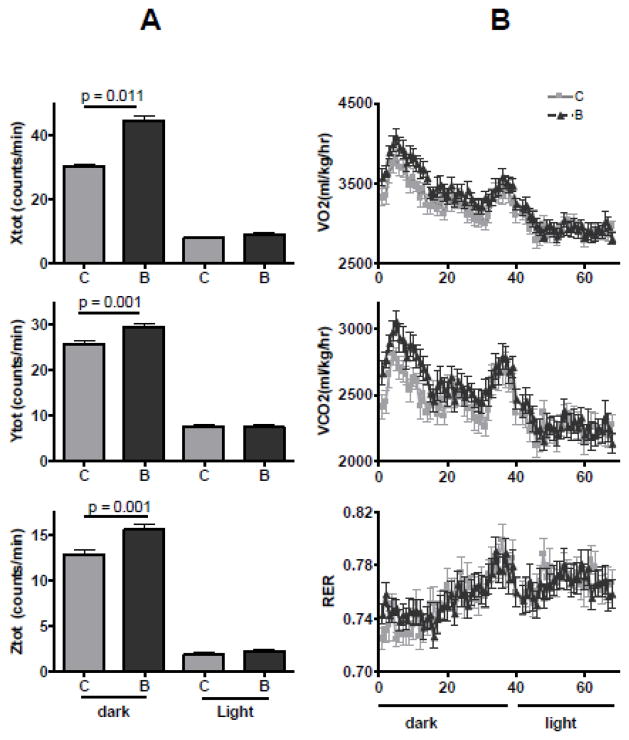

Effect of BME supplementation on spontaneous locomotion and respiration activity

In the 5th month into the intervention, animals were assessed using the Oxymax system for real time locomotion and respiration. As shown in Figure 2A, in the dark period, BME-treated mice displayed increased locomotion in X-, Y-, and Z- directions compared to the control. This increase in locomotion was correlated with an increase in O2 consumption and CO2 production (Figure 2B). Since no difference in either activity or respiration was found in the light period when mice were inactive, mean metabolic activity was calculated for the dark period only and was found to be increased in the BME-treated mice (Table 4). The respiratory exchange rate was unchanged between the two groups (RER, 0.75 at dark and 0.77 at light), showing that lipids were used as the all time primary fuel, as typically found in obese mice consuming a high fat diet 36. The increase in locomotion in the BME-treated mice may be related to better muscle strength and/or (neurological) motivation to move around. The associated increase in respiration without increasing food intake may also have contributed to less gain of fat mass in the BME-treated mice (Figure 1).

Figure 2. Effect of BME on spontaneous locomotion and respiration.

(A) Means of locomotion counts along the X-, Y-, and Z- directions during the dark (7 pm – 7 am) and light (7 am – 7 pm) periods. (B). Minute-to-minute recording of O2 consumption and CO2 production rates. Results are shown as means ± se, n = 16, t test (C: control, B: BME-treated).

Table 4.

The effect of BME on metabolic activity (t test, n = 16).

| Parameter | O2 consumption, ml/kg | CO2 production, ml/kg |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 3329 ±32 | 2513 ± 22 |

| BME | 3522 ± 38 | 2662 ± 26 |

| p value | 0.001 | 0.001 |

Effect of BME supplementation on abdominal fat cell size and fat tissue inflammation

Fat tissue macrophage infiltration and cytokine production is a major cause for chronic low-grade inflammation in obese individuals. As expected, epididymal fat from control animals was marked by extensive accumulation of crown-like structures (Figure 3A), a typical phenotype of inflamed fat tissue in obesity 37. This phenotype was largely attenuated by BME supplementation (Figure 3A). Quantitative image analysis shows that the percentage of the area occupied by crown-structures in epididymal fat was reduced from 12.7 ± 4.3% for the control to 0.83 ± 0.1% for the BME-treated mice (p = 0.02, n = 5). Real-time PCR analysis shows that BME supplementation reduced mRNA expression of selected cytokines including TNFα, IL-6, IFNγ, and iNOS in epididymal fat (Figure 3B), as would be predicted based on the histological observations.

Figure 3. Effect of BME on epididymal fat morphology, fat cell size, and cytokine expression.

(A) Representative hematoxylin and eosin staining for epididymal fat. Crown-like structures resembling macrophage infiltrationis marked by an arrow. (B) Expression of mRNA for inflammation markers. Results are shown as means ± se, t test, n = 7 per group. (C) Companion measurements of fat cell size distribution, measured from seven different animals per group, five different views per animal.

BME supplementation also increased the percentage of smaller fat cells and decreased the percentage of larger fat cells (Figure 3C). The mean cross section of fat cells was reduced from 13,000 ± 1,000 μm2 in control to 11,000 ± 1,000 μm2 in BME-treated mice (p = 0.006, n =5). Together with the finding of reduced fat mass (Figure 1), our results suggest that BME supplementation may have restrained diet-induced fat cell enlargement. Since smaller fat cells are generally metabolically healthier than the larger ones 38, it is not surprising that fat tissue of the BME-treated mice was less inflamed (Figure 3A&B).

To further assess the effect of BME supplementation on fat tissue inflammation and stress responses, we analyzed markers for NFκB activity, the master transcription factor for inflammatory cytokines. As shown in Figure 4A, expression of phosphorylated (activated) forms of NFκB-p65 and -p50 subunits were both reduced in BME-treated animals. This is consistent with the reduction in cytokine mRNA (Figure 3B) and in agreement with our prior report that BME inhibits NFκB activity in cultured pre-adipocytes 28. In addition, we measured the fat tissue expression of mitochondrial uncoupling proteins (UCPs), the established ROS-induced molecular targets 39. As expected, BME supplementation reduced expression of UCP2, the white fat-specific uncoupling protein (Figure 4B, left panel). Expression of UCP1, the brown fat-specific uncoupling protein, was at a much lower level than UCP2 in the epididymal fat, but was still substantially reduced by BME (Figure 4B, middle panel). Expression of UCP3, the muscle-specific uncoupling protein, was also very low in epididymal fat but was not affected by BME (Figure 4B, right panel), as would be expected by its muscle specificity.

Figure 4. Effect of BME on expression of stress markers in epididymal fat.

(A) Expression of phosphor-p65 and phosphor-p50. (B) Expression of uncoupling protein 1–3, quantified relatively to the housekeeping gene, hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase (HPRT). (C) Expression of the ER stress marker GADD153 and ER chaperone GRP78. All bar graphs are shown as means ± se. Each was calculated from results of n = 7 – 10 animals with four representative results shown for each group.

Since oxidant stress is tightly and often directly related to endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress 40, 41, we also assessed the effect of BME supplementation on markers for ER stress in epididymal fat. As expected, the growth arrest- and DNA damage-inducible gene 153 (GADD153), a classic ER stress marker 42, was expressed at a lower level in BME-treated animals than the control (Figure 4C). Expression of the ER chaperone GRP78, the key element for the unfold protein response that helps to relieve ER stress 43, was similar between the two groups (Figure 4C). Taken together, these results suggested that long-term BME supplementation reduced fat tissue stress and inflammation in diet-induced obese mice.

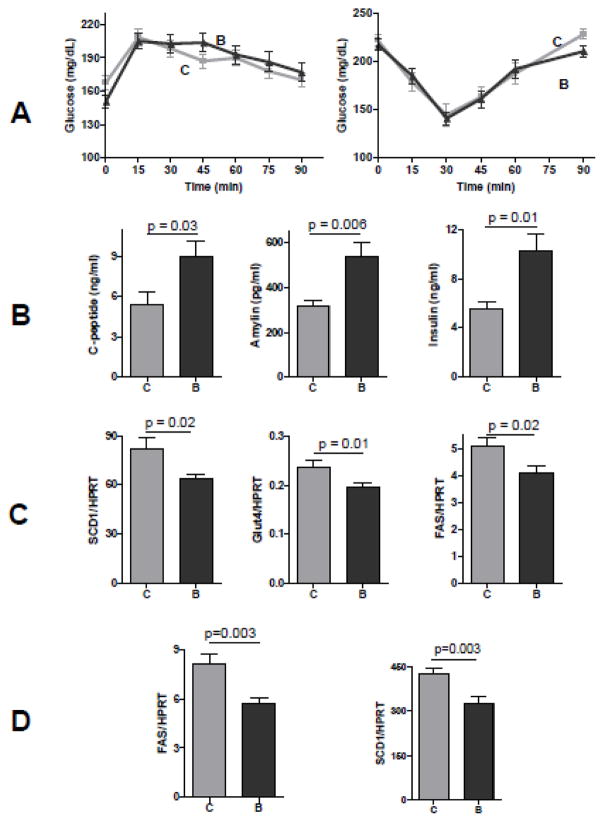

Effect of BME supplementation on insulin sensitivity

Weight loss typically correlates with improved insulin resistance and functional performance 44, 45. This may have led to a widely held opinion that obesity-related fat tissue inflammation are the cause for insulin resistance, which in turn underlies other metabolic and functional disorders 44. Unexpectedly, we found that BME-treated mice displayed no improvement of insulin tolerance (Figure 5A, right panel) or pyruvate tolerance (Figure 5A, left panel). Furthermore, plasma analysis revealed almost a two-fold increase in plasma insulin concentration with a similar increase in C-peptide and amylin in BME-treated animals (Figure 5B). This shows that pancreatic insulin secretion was enhanced, a conventional marker for insulin resistance 46. Histological analysis detected no morphological abnormality in the pancreas of BME-treated animals, although both groups displayed similarly mild islet hyperplasia (not shown).

Figure 5. Effects of long-term BME supplementation on insulin sensitivity.

(A) Insulin tolerance and pyruvate tolerance tests (■: control, darker triangle: ▲: BME, n = 16 for each data point). (B) Plasma concentrations of insulin, C-peptide, and its co-secreted peptide amylin (means ± se, n = 16, t test). (C) Epididymal fat tissue expression of selected lipogenic genes of fatty acid synthase (FAS), stearoyl-CoA desaturase 1 (SCD1), and Glucose transporter (Glut4), (D) Liver expression of FAS and SCD1. Results are means ± se, n = 12, t test.

Because insulin-stimulated glucose uptake occurs primarily in skeletal muscle (measured by insulin tolerance) and insulin-mediated suppression of gluconeogenesis occurs primarily in the liver (measured by pyruvate tolerance), the lack of difference in both tests suggest that BME supplementation did not improve acute insulin sensitivity in muscle and liver. The elevation of plasma insulin concentration actually suggests a reduction in the steady-state insulin sensitivity in BME-treated mice. Since insulin resistance is often caused by fat infiltration into liver and muscle 47, 48, we analyzed the triglyceride concentrations in the tissue homogenates. Fat infiltration was actually reduced in the liver and muscle of BME-treated animals (Table 5). Hence, the paradoxical reduction in insulin sensitivity in liver and muscle did not seem to be caused by fat infiltration into these organs.

Table 5.

The effect of BME on fat infiltration into skeletal muscle and liver (t test, n = 16 per group).

| Tissue | Skeletal muscle, mg/g | Liver, mg/g |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 22.9 ± 15 | 58 ± 5 |

| BME | 19.3 ± 0.9 | 42 ± 3 |

| p value | 0.06 | 0.05 |

Fat tissue is another major organ that is subject to metabolic regulation by insulin. Despite an increase in plasma insulin concentration, we found no increase in fat tissue expression of markers for insulin signaling, including phosphorylation of Akt, the pivotal kinase for insulin-mediated metabolic effects, and its selected downstream targets S6 and (Figure 6A), suggesting that BME may desensitize insulin signaling. Expression of fat tissue lipogenic genes including fatty acid synthase (FAS), stearoyl-coenzyme A desaturate (SCD-1), and glucose transporter 4 (Glut4), were decreased in BME-treated animals (Figure 5C), all are known for their response to insulin-mediated induction 49. Similar decrease in mRNA of FAS and SCD1 was found in the liver of BME-treated animals (Figure 5D).

Figure 6. Effect of BME on insulin signaling.

(A) Fat tissue expression of phospho-AktTh308, phospho-AktSer473, phospho-S6Ser235/236, and phospho-4EBP1Th37/46, in reference to total Akt, using actin as the loading control, each lane represents one single animals. Blotts for additional animals for each group gave similar results. (B) Insulin-stimulated Akt phosphorylation in cultured HepG2 cells and its attenuation by pre-treatment with BME at indicated concentrations. Results are representative of three independent experimental repeats.

To test whether BME may have a direct inhibitory effect on insulin signaling, we co-treated cultured HepG2 cells with BME and insulin. As shown in Figure 6B, insulin alone increased Akt phosphorylation, but this induction was dose-dependently attenuated by pre/co-treatment with BME. Thus, our data collectively indicate that BME directly desensitizes insulin signaling, as would be expected based on the literature 18.

Effect of BME supplementation on plasma concentration and liver expression of C-reactive protein

Insulin resistance is often associated with low grade chronic inflammation in obesity, but the cause-and-effect relationship remains inconclusive. Paradoxically, BME-treated mice displayed increased insulin resistance but decreased fat tissue inflammation under our experimental conditions. To determine how this effect correlates with systemic inflammation, we measured plasma concentration of C-reactive protein (CRP), a well characterized liver-secreted peptide that acts as a marker for systemic inflammation 50. As shown in Figure 7A, plasma CRP concentration was lower in BME-treated animals than the control, in parallel with reduced CRP expression in the liver (Figure 7B). This finding provides the evidence that BME supplementation reduced inflammation not only in fat tissue but in the liver and at the systemic level as well. Interestingly, our data are in-line with a previous report that reduction in CRP correlates with reduced plasma leptin in obese humans after weight loss 50.

Figure 7. Effect of BME on plasma concentration of C-reactive protein and its liver expression.

(A) Plasma concentration of C-reactive protein (CRP), (B) Hepatic expression of CRP mRNA, relative to a housekeeping gene, HPRT. Results are shown as means ± se, n = 16 for each group, t test.

Discussion

Our study demonstrated that supplementation of low dose BME (2.0–2.5 mM in drinking water) to mice with pre-existing diet-induced obesity for six months reduced fat mass and fat cell sizes, in association with reduced inflammation in fat tissue, liver, and at the systemic level. BME-treated mice also showed increased skeletal muscle mass, reduced plasma lipid peroxidation, and reduced muscle and liver fat infiltration. More importantly, BME-treated mice showed improvement in spontaneous locomotion and metabolic activity as well as in gripping strength over the control mice. These results provided the first quantitative evidence that long-term supplementation of low dose BME can be metabolically and functionally beneficial to middle-age mice with pre-existing diet-induced obesity. These results, together with previous studies that reported BME-mediated extension of lifespan and preservation of neurological function in rodents 19–21, collectively support further exploration of the feasibility to use this or other relevant thiol antioxidants for treatment of obesity and related functional disorders.

The mechanisms for these observations, however, are still not clear. It has been shown that chronic low-grade inflammation causes muscle weakness and fatigue 51, 52, which may explain why our control (obese) mice were losing gripping strength overtime. Thus, interventions that reduce inflammation are expected to exert a positive impact on muscle strength. This is indeed what we observed in the BME-treated mice that displayed reduced inflammation and muscle fat infiltration, with a parallel increase in muscle mass and better preservation of gripping strength over the control animals. This effect may also contribute to the observed difference in spontaneous activity. However, modification of cognitive function, either from BME directly, as suggested in previous studies 23, or indirectly from modified plasma cytokine profile might also contribute. Since obesity in some aspect resembles a situation of accelerated aging, we would speculate that by reducing fat mass and fat tissue inflammation, long-term supplementation of the thiol antioxidant might delay the premature cognitive decline in the obese mice. Further investigation will be required to evaluate this hypothesis.

An unexpected observation from this work is the apparently paradoxical association between an improved functional outcome and reduced insulin sensitivity in mice after BME supplementation. Our results are very similar to a recent report showing that another thiol antioxidant, NAC, reduced fat mass but increased insulin resistance in obese non-diabetic humans 18. Both findings are in complete agreement with the literature that adequate level of pro-oxidants (e.g. peroxides) is essential for proper insulin signaling transduction 10–17. The reduction of insulin sensitivity could be related to the over-efficient ROS scavenging by the thiol antioxidants, as evidenced by our in vitro data that BME could directly reduce insulin-stimulated Akt phosphorylation in cultured liver cells.

The exact mechanism that raises plasma insulin concentration remains puzzling but a possibility that BME directly acts on β-cells to cause hyperinsulinemia is unlikely, in part because several previous studies have shown that exposure to BME reduces, rather than increases, insulin secretion 53, 54. It should be noted that at sacrifice, when blood samples were taken for insulin assays, food remained in the stomach, suggesting that elevated insulin levels might reflect a response to food rather than an altered secretory response. If mice consumed food and water in parallel, the rise of plasma BME concentration is expected to temporally overlap with the rise of food-induced insulin secretion. In other words, the BME-mediated ROS-scavenging effect could rise within the time frame of postprandial surge in insulin. Indiscriminate and yet overly efficient ROS scavenging in the BME-treated animals might thus dampen the insulin signal transduction in muscle, liver and fat; causing the pancreas to respond by increasing insulin secretion, thus raising the plasma insulin concentration.

Although it is widely documented that excessive production of pathological levels of ROS can cause insulin resistance 55, there is no evidence that insulin resistance alone is responsible for its associated metabolic disorders. In certain pathophysiological conditions, insulin resistance is suggested as a mechanism of self-protection to defend a tissue/organ against excessive fuel loading 4, 56. Indeed, the dampening of insulin sensitivity in adipose tissue, muscle, and liver in BME-treated animals might have contributed to the reduction of fat store in these organs as we found in this work. In this regard, our data provided a convincing case that long-term treatment with a low dose thiol antioxidant may reduce body oxidant stress and improve functional outcome independent of its negative impact on insulin sensitivity. Nevertheless, it is important to note that while a moderate reduction in tissue insulin sensitivity can be protective against excess fat infiltration, the feedback stimulation of pancreatic insulin secretion, if unbridled, may eventually lead to islet exhaustion. In this regard, additional studies are required to determine whether a lower dose or intermittent consumption of BME or other thiol antioxidants will preserve the health benefit without sustaining insulin hypersecretion in obese individuals. Alternatively, it may be important to use proper adjunctive products to counteract the insulin desensitizing effect, as previously demonstrated 18.

Conclusion

In summary, we found that long-term supplementation of low dose thiol antioxidant BME improved the physical and metabolic outcomes from middle-aged mice with pre-existing and continuing diet-induced obesity. The health benefit of BME is correlated with the anti-inflammatory effect detected in fat tissue, liver, and at the systemic level. Future studies to compare BME or its related thiol compound, such as NAC, to other common antioxidants such as vitamins and polyphenols may provide additional information for the mechanism and therapeutic roles of antioxidant supplements for treatment of obesity and metabolic disorders.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank Mr. Wentao Liang and Ms. Yahui Li for technical assistance.

Funding: This work was supported by NIH grants R01 DK56690 (WG, BEC), AG037859 (WG), AG013925 (JLK), and DK50456 (JLK). ALS is supported by the USDA AFRI/NIFA fellowship (2012-01287). The sponsors did not have a role in the study design; collection, analysis, or data interpretation; manuscript writing; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Abbreviations

- BME

β-mercaptoethanol

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- NAC

N-acetylcysteine

- HOMA-IR

homeostatic model of assessment for insulin resistance

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- AST

aspartate aminotransferase

- TBARS

thiobarbituric acid reactive substances

- UCP

uncoupling protein

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- GADD153

growth arrest- and DNA damage-inducible gene 153

- GRP78

78 kDa glucose-regulated protein

- FAS

fatty acid synthase

- SCD-1

stearoyl-coenzyme A desaturate 1

- Glut4

glucose transporter 4

- ITT

insulin tolerance test

- PTT

pyruvate tolerance test

- CRP

C-reactive protein

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors do not have any conflicts of interest.

Author Contribution: BEC and WG conceived the study. SW and WG conducted the experiments. HAS and JAH performed the NMR measurements. All authors were involved in writing the paper and final approval of the submitted version.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bondia-Pons I, Ryan L, Martinez JA. Oxidative stress and inflammation interactions in human obesity. J Physiol Biochem. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s13105-012-0154-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bisbal C, Lambert K, Avignon A. Antioxidants and glucose metabolism disorders. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2010;13:439–46. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e32833a5559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Corkey BE, Shirihai O. Metabolic master regulators: sharing information among multiple systems. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2012;23:594–601. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2012.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hoehn KL, Salmon AB, Hohnen-Behrens C, et al. Insulin resistance is a cellular antioxidant defense mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:17787–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902380106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Avignon A, Hokayem M, Bisbal C, Lambert K. Dietary antioxidants: do they have a role to play in the ongoing fight against abnormal glucose metabolism? Nutrition. 2012;28:715–21. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2012.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Souza GA, Ebaid GX, Seiva FR, et al. N-acetylcysteine an allium plant compound improves high-sucrose diet-induced obesity and related effects. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2008;2011:643269. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nen070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bogdanski P, Suliburska J, Szulinska M, Stepien M, Pupek-Musialik D, Jablecka A. Green tea extract reduces blood pressure, inflammatory biomarkers, and oxidative stress and improves parameters associated with insulin resistance in obese, hypertensive patients. Nutr Res. 2012;32:421–7. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2012.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poulsen MM, Vestergaard PF, Clasen BF, et al. High-dose resveratrol supplementation in obese men: an investigator-initiated, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial of substrate metabolism, insulin sensitivity, and body composition. Diabetes. 2013;62:1186–95. doi: 10.2337/db12-0975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chowdhury KK, Legare DJ, Lautt WW. Interaction of antioxidants and exercise on insulin sensitivity in healthy and prediabetic rats. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2013;91:570–7. doi: 10.1139/cjpp-2012-0425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pomytkin IA. H2O2 Signalling Pathway: A Possible Bridge between Insulin Receptor and Mitochondria. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2012;10:311–20. doi: 10.2174/157015912804143559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.May JM, de Haen C. Insulin-stimulated intracellular hydrogen peroxide production in rat epididymal fat cells. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:2214–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heffetz D, Zick Y. H2O2 potentiates phosphorylation of novel putative substrates for the insulin receptor kinase in intact Fao cells. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:10126–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Droge W. Oxidative aging and insulin receptor signaling. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60:1378–85. doi: 10.1093/gerona/60.11.1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.May JM, de Haen C. The insulin-like effect of hydrogen peroxide on pathways of lipid synthesis in rat adipocytes. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:9017–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mukherjee SP. Mediation of the antilipolytic and lipogenic effects of insulin in adipocytes by intracellular accumulation of hydrogen peroxide. Biochem Pharmacol. 1980;29:1239–46. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(80)90280-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Little SA, de Haen C. Effects of hydrogen peroxide on basal and hormone-stimulated lipolysis in perifused rat fat cells in relation to the mechanism of action of insulin. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:10888–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ludvigsen C, Jarett L. Similarities between insulin, hydrogen peroxide, concanavalin A, and anti-insulin receptor antibody stimulated glucose transport: increase in the number of transport sites. Metabolism. 1982;31:284–7. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(82)90066-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hildebrandt W, Hamann A, Krakowski-Roosen H, et al. Effect of thiol antioxidant on body fat and insulin reactivity. J Mol Med (Berl) 2004;82:336–44. doi: 10.1007/s00109-004-0532-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Click RE. Longevity of SLE-prone mice increased by dietary 2-mercaptoethanol via a mechanism imprinted within the first 28 days of life. Virulence. 2010;1:516–22. doi: 10.4161/viru.1.6.13805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Click RE. Obesity, longevity, quality of life: alteration by dietary 2-mercaptoethanol. Virulence. 2010;1:509–15. doi: 10.4161/viru.1.6.13803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heidrick ML, Hendricks LC, Cook DE. Effect of dietary 2-mercaptoethanol on the life span, immune system, tumor incidence and lipid peroxidation damage in spleen lymphocytes of aging BC3F1 mice. Mech Ageing Dev. 1984;27:341–58. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(84)90057-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beregi E, Regius O, Rajczy K, Boross M, Penzes L. Effect of cigarette smoke and 2-mercaptoethanol administration on age-related alterations and immunological parameters. Gerontology. 1991;37:326–34. doi: 10.1159/000213280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fischer HD, Wustmann C, Rudolph E, et al. Effect of 2-mercaptoethanol on posthypoxic and age-related biochemical and behavioural changes in mice and rats. Biomed Biochim Acta. 1990;49:1085–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Makinodan T, Albright JW. Restoration of impaired immune functions in aging animals. III. Effect of mercaptoethanol in enhancing the reduced primary antibody responsiveness in vivo. Mech Ageing Dev. 1979;11:1–8. doi: 10.1016/0047-6374(79)90059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Penzes L, Fischer HD, Wustmann C, et al. Effect of 2-mercapto-ethanol on some brain biochemical characteristics and behavioural changes in the ageing CBA/Ca mice. Pharmacology. 1990;40:343–8. doi: 10.1159/000138683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.White K, Bruckner JV, Guess WL. Toxicological studies of 2-mercaptoethanol. J Pharm Sci. 1973;62:237–41. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600620211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guo W, Wong S, Li M, et al. Testosterone plus low-intensity physical training in late life improves functional performance, skeletal muscle mitochondrial biogenesis, and mitochondrial quality control in male mice. PLoS One. 2012;7:e51180. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guo W, Li Y, Liang W, et al. Beta-mecaptoethanol suppresses inflammation and induces adipogenic differentiation in 3T3-F442A murine preadipocytes. PLoS One. 2012;7:e40958. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0040958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ii H, Yokoyama N, Yoshida S, et al. Alleviation of high-fat diet-induced fatty liver damage in group IVA phospholipase A2-knockout mice. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8089. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Considine RV, Sinha MK, Heiman ML, et al. Serum immunoreactive-leptin concentrations in normal-weight and obese humans. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:292–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199602013340503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Varady KA, Tussing L, Bhutani S, Braunschweig CL. Degree of weight loss required to improve adipokine concentrations and decrease fat cell size in severely obese women. Metabolism. 2009;58:1096–101. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2009.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Berg AH, Combs TP, Scherer PE. ACRP30/adiponectin: an adipokine regulating glucose and lipid metabolism. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2002;13:84–9. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(01)00524-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Briggs DB, Giron RM, Malinowski PR, Nunez M, Tsao TS. Role of redox environment on the oligomerization of higher molecular weight adiponectin. BMC Biochem. 2011;12:24. doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-12-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Briggs DB, Jones CM, Mashalidis EH, et al. Disulfide-dependent self-assembly of adiponectin octadecamers from trimers and presence of stable octadecameric adiponectin lacking disulfide bonds in vitro. Biochemistry. 2009;48:12345–57. doi: 10.1021/bi9015555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Singh-Manoux A, Czernichow S, Elbaz A, et al. Obesity phenotypes in midlife and cognition in early old age: The Whitehall II cohort study. Neurology. 2012;79:755–62. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182661f63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koves TR, Ussher JR, Noland RC, et al. Mitochondrial overload and incomplete fatty acid oxidation contribute to skeletal muscle insulin resistance. Cell Metab. 2008;7:45–56. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Strissel KJ, Stancheva Z, Miyoshi H, et al. Adipocyte death, adipose tissue remodeling, and obesity complications. Diabetes. 2007;56:2910–8. doi: 10.2337/db07-0767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ravussin E, Smith SR. Increased fat intake, impaired fat oxidation, and failure of fat cell proliferation result in ectopic fat storage, insulin resistance, and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;967:363–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Giardina TM, Steer JH, Lo SZ, Joyce DA. Uncoupling protein-2 accumulates rapidly in the inner mitochondrial membrane during mitochondrial reactive oxygen stress in macrophages. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1777:118–29. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pallepati P, Averill-Bates DA. Activation of ER stress and apoptosis by hydrogen peroxide in HeLa cells: protective role of mild heat preconditioning at 40 degrees C. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1813:1987–99. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu AX, He WH, Yin LJ, et al. Sustained endoplasmic reticulum stress as a cofactor of oxidative stress in decidual cells from patients with early pregnancy loss. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:E493–7. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-2192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang XZ, Lawson B, Brewer JW, et al. Signals from the stressed endoplasmic reticulum induce C/EBP-homologous protein (CHOP/GADD153) Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:4273–80. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.8.4273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li J, Lee AS. Stress induction of GRP78/BiP and its role in cancer. Curr Mol Med. 2006;6:45–54. doi: 10.2174/156652406775574523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van Greevenbroek MM, Schalkwijk CG, Stehouwer CD. Obesity-associated low-grade inflammation in type 2 diabetes mellitus: causes and consequences. Neth J Med. 2013;71:174–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee BC, Lee J. Cellular and molecular players in adipose tissue inflammation in the development of obesity-induced insulin resistance. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ahlkvist L, Brown K, Ahren B. Upregulated insulin secretion in insulin-resistant mice: evidence of increased islet GLP1 receptor levels and GPR119-activated GLP1 secretion. Endocr Connect. 2013;2:69–78. doi: 10.1530/EC-12-0079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vinolo MA, Rodrigues HG, Festuccia WT, et al. Tributyrin attenuates obesity-associated inflammation and insulin resistance in high-fat-fed mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2012;303:E272–82. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00053.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kirkland JL, Tchkonia T, Pirtskhalava T, Han J, Karagiannides I. Adipogenesis and aging: does aging make fat go MAD? Exp Gerontol. 2002;37:757–67. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(02)00014-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.O’Brien RM, Streeper RS, Ayala JE, Stadelmaier BT, Hornbuckle LA. Insulin-regulated gene expression. Biochem Soc Trans. 2001;29:552–8. doi: 10.1042/bst0290552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pardina E, Ferrer R, Baena-Fustegueras JA, et al. Only C-reactive protein, but not TNF-alpha or IL6, reflects the improvement in inflammation after bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2011;22:131–9. doi: 10.1007/s11695-011-0546-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Trock D. Tired, achy, and overweight, the inflammatory nature of obesity. J Clin Rheumatol. 2009;15:50. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0b013e31819559f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vincent HK, Raiser SN, Vincent KR. The aging musculoskeletal system and obesity-related considerations with exercise. Ageing Res Rev. 2012;11:361–73. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Asfari M, Janjic D, Meda P, Li G, Halban PA, Wollheim CB. Establishment of 2-mercaptoethanol-dependent differentiated insulin-secreting cell lines. Endocrinology. 1992;130:167–78. doi: 10.1210/endo.130.1.1370150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pi J, Bai Y, Zhang Q, et al. Reactive oxygen species as a signal in glucose-stimulated insulin secretion. Diabetes. 2007;56:1783–91. doi: 10.2337/db06-1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Henriksen EJ, Diamond-Stanic MK, Marchionne EM. Oxidative stress and the etiology of insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;51:993–9. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Corkey BE. Diabetes: have we got it all wrong? Insulin hypersecretion and food additives: cause of obesity and diabetes? Diabetes Care. 2012;35:2432–7. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]