Abstract

Articular cartilage was predicted to be one of the first tissues that could successfully be regenerated, but this proved not to be the case. In contrast, bone but also vasculature and cardiac tissues have seen numerous successful reparative approaches, despite consisting of multiple cell and tissue types and thus possessing more complex design requirements. Here, we use bone regeneration successes to highlight cartilage regeneration challenges, namely selecting appropriate cell sources and scaffolds, creating biomechanically suitable tissues, and integrating to native tissue. Also discussed are technologies addressing hurdles of engineering a tissue possessing mechanical properties unmatched in man-made materials and functioning in environments unfavorable to neotissue growth.

Nearly two decades ago the concept of tissue-engineering promised healing damaged tissues and organs using living, functional constructs. By manipulating cells, scaffolds, and stimuli, the premise was that tissues could be generated, which, upon implantation, would integrate to native tissues and restore functions lost to trauma, disease, or aging (1). Tissue-engineers recognized that the first targets would be tissues with homogeneous structure and few cell types (2). Due to diffusion limitations it was also anticipated that these would be thin, avascular tissues. Thus, the first cell-based products would be for skin and articular cartilage due to their almost two-dimensional nature. However, it is now understood that despite its more complex composition, including the presence of multiple cell types and vascularity, bone exhibits a high level of innate repair capability that is not present in cartilage, and has thus seen more development as a target for regeneration than cartilage.

Articular cartilage is the elegantly organized tissue that allows for smooth motion in diarthrodial joints. Our bodies possess a number of distinct cartilages, the hyaline cartilages of the nasal septum, tracheal rings, and ribs; the elastic cartilages of the ear and epiglottis; and the fibrocartilages of the intervertebral discs, temporomandibular joint disc, and knee meniscus. Articular cartilage is unique in its weight-bearing and low friction capabilities. Its damage can impair joint function leading to disability. Unlike the majority of tissues, articular cartilage is avascular. Without access to abundant nutrients or circulating progenitor cells and possessing a nearly acellular nature, cartilage lacks innate abilities to mount a sufficient healing response (Fig. 1). Thus, damaged tissue is not replaced with functional tissue, requiring surgical intervention (3). Traditional techniques for cartilage repair include marrow stimulation, allografts, and autografts (Fig. 2). While successful in some aspects, each of these techniques has limitations. Marrow stimulation results in fibrocartilage of inferior quality that does not persist; allografts suffer from lack of integration, loss of cell viability due to graft storage, and concerns of disease transmission; and autografts also lack integration, and require additional defects (3).

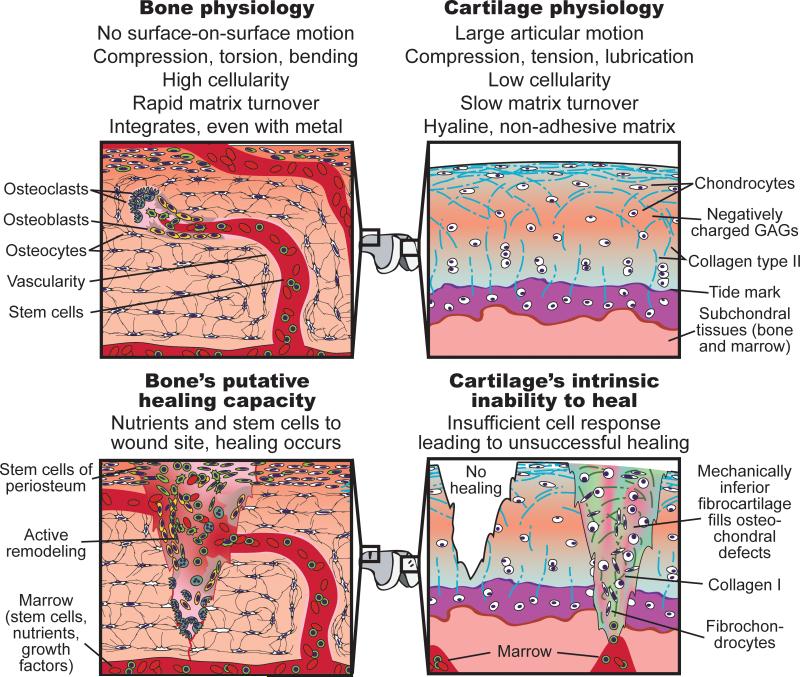

Fig. 1.

Differences in the physiologic environment and cellular make-up of bone and cartilage have profound effects on the potential to engineer these tissues. Through the presence of stem cells in marrow and in the periosteum, and access to abundant nutrients via vasculature, bone possesses inherent regenerative capability that can be harnessed in regenerative therapies. Cartilage's hypocellularity and lack of nutrient supply, coupled with the inability of bone marrow MSCs or resident chondroprogenitor cells to generate hyaline ECM, result in a tissue unable to mount a functional healing response. Thus, in contrast to bone's ability to heal, cartilage needs more robust exogenous approaches to achieve satisfactory regeneration.

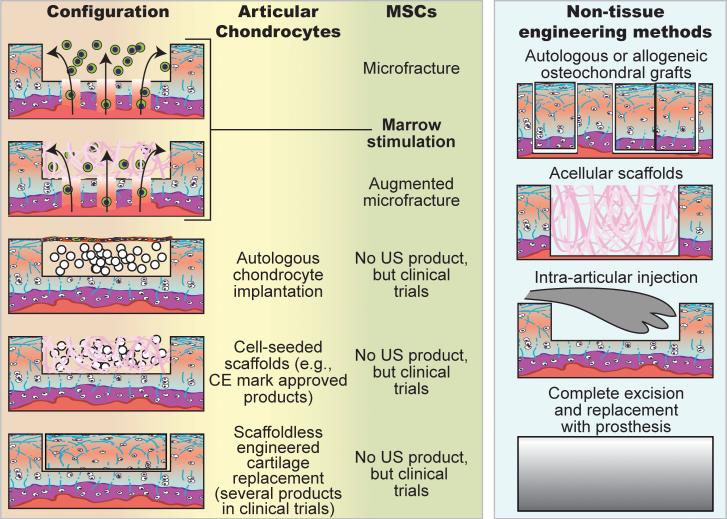

Fig. 2.

Various clinical strategies regenerate cartilage using chondrocytes or MSCs. Microfracture involves subchondral bone penetration to release bone marrow that forms a stem cell-rich clot. Augmented microfracture adds a scaffold to the microfracture technique to concentrate and aid in stem cell differentiation. Acellular scaffolds are also used in full-thickness defects. Autologous chondrocyte implantation involves harvest of the patient's chondrocytes; the cells are expanded in vitro, and then placed under a collagen membrane sutured over the defect site. Advancement of this technique involves seeding chondrocytes onto a scaffold and culturing in vitro prior to implantation. Scaffoldless engineered cartilage formed in vitro with chondrocytes is also used with two products currently undergoing clinical trials. In aforementioned strategies, MSCs can be used instead of chondrocytes; however, products based on these technologies are at earlier stages of development. Osteochondral grafts taken either from less-load bearing regions of the patient's own joint or cadaveric joints are implanted to fill focal defects. Intra-articular injections (e.g., hyaluronan) reduce the symptoms of cartilage degeneration, but the effects are only temporary. Total joint replacement is the final option when cartilage damage is so extensive that no other therapies can be effective.

Limitations of making an engineered cartilage for clinical use

For load-bearing tissues, correlations between structure and function must be understood to establish tissue-engineering design criteria. Cartilage viscoelastic properties manifest from its extracellular matrix (ECM) composition of water (70-80%), collagen (50-75%), and glycosaminoglycans (GAGs) (15-30%) (3). This composition provides cartilage with compressive, tensile, and frictional properties that enable survival and function within the biomechanically arduous joint environment.

Successful methods to regenerate bone, but not cartilage, stem from a discrepancy between their innate repair responses (Fig. 1) (4). A large number of cells (osteoclasts and osteoblasts) are involved in perpetual bone breakdown and re-modeling. Also, the periosteum and bone marrow contain stem cells that can differentiate into bone-producing cells. Bone's extensive vascularity provides abundant nutrients and blood-borne proteins that stimulate tissue repair. Defects in bone can thus be self-repaired up to a critical size, although regeneration in large bony defects requiring vascularization continues to be a problem. In contrast to bone's cellularity, cartilage's few cells exhibit low metabolic activity. Its scarce resident stem cells, recently identified, appear to require significant in vitro manipulation to produce cartilage (3, 5). Few, if any, cells are specialized in cartilage remodeling; chondroclasts have only been described for calcified or hypertrophic matrices. Cartilage is dependent on synovial fluid perfusion to meet its nutritional needs. Without cells and factors conducive to healing, even small, superficial cartilage defects fail to heal (3).

Current bone regeneration products are used in cases where external support is provided by plates or cages or where the implant is not intrinsic to the stability of the bony structure. These indications allow sufficient mechanotransduction for stimulation of bone growth, and thus successful bone regeneration, without necessarily recapitulating native biomechanical properties. For cartilage, comparable indications do not exist, and the generated tissue must be strong, yet highly deformable, and lubricious while exhibiting time-dependency in its stress-strain response. Cartilage's biomechanical environment, consisting of forces over a large range of motion, can take a devastating toll on neocartilage lacking adequate biomechanical properties.

Cell types for cartilage regeneration

Whether it is stem cells or terminally differentiated cells, the most important selection criterion is the ability to produce tissue-specific ECM. Secondary criteria include ease of acquisition and induction toward the desired phenotype. For bone regeneration, mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) fulfill the desired criteria, so other cells are seldom used (6). For cartilage, neither MSCs nor chondrocytes, the resident cells of cartilage, have shown this same degree of success.

In vivo, periosteum and bone marrow-derived MSCs migrate to repair small defects (Fig. 1) (4). For defects too large to heal naturally (critical size defects), bone repair employing in situ MSCs can be augmented by osteoconductive or osteoinductive scaffolds with or without growth factors. Isolated MSCs, from bone marrow or adipose tissue (termed ASCs (7)), also retain the ability in vitro to create bone (6).

MSC use in cartilage regeneration includes microfracture, cell slurry or construct implantation, and recruitment from the synovial membrane (8) (Fig. 2). MSCs can differentiate into numerous cell types, including chondrocytes, fibrochondrocytes, and hypertrophic chondrocytes, resulting in a mixture of cartilaginous, fibrous, and hypertrophic tissues (9, 10). Despite short-term clinical success, this repair tissue eventually fails as it does not possess functional mechanical properties. For example, while fibrocartilaginous repair tissue from microfracture results in initially enhanced clinical knee function scores, over 2 years it degrades and scores decline (9). Scaffolds used with microfracture enhance hyaline quality and increase fill percentage, but fibrous tissue still results (11). In conjunction with matrix formation, MSC anti-inflammatory effects may be important in alleviating symptoms (12). If in situ MSC differentiation is insufficient for long-term efficacy, can in vitro manipulation yield hyaline tissues? Unfortunately, chondro-differentiation of MSCs results in an unnatural differentiation pathway that is unlike either endochondral ossification or permanent cartilage formation in that markers of hyaline cartilage (collagen type II and SOX-9), hypertrophy (collagen type X and MMP13), and bone (osteopontin and bone sialoprotein) are expressed concurrently (13).The success of MSC-based techniques may remain limited if the presence of fibrous and hypertrophic tissue cannot be eliminated.

Therapies employing autologous chondrocytes suffer from requiring two surgeries (for cell harvest and implantation) and forming fibrous repair tissue. It may seem counterintuitive that the constituent cells of cartilage cannot produce a purely hyaline tissue. However, to obtain sufficient chondrocyte numbers for therapy, the required in vitro expansion induces dedifferentiation. Expansion outside of the natural biochemical and biomechanical milieu results in a fibroblastic phenotype, as evidenced in autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI) procedures (Fig. 2), where over 90% of the repair tissue is fibrocartilaginous (14). Research in chondrocyte redifferentiation in vitro has resulted in several products under development that yield hyaline-like neotissue in 27-77% of biopsies (15, 16). To further increase the amount of hyaline repair tissue, other products use younger (more chondrogenic) allogeneic chondrocytes, omit the scaffold material, and apply physiologically-inspired stimuli (17, 18).

Allogeneic and xenogeneic cells are also investigated since cartilage is perceived as immunoprivileged (3). The concept that a dense matrix protects transplanted chondrocytes is bolstered by the fact that fresh osteochondral allografts restore function without antigen matching, extensive processing, or immunosuppressives. The seemingly impenetrable matrix is nonetheless subject to immune-related breakdown, as is evident in inflammatory arthritis. Also, cartilage repair studies often use non-quantitative assessments such as swelling to examine immunogenicity; quantity and type of immune cells, cytokines, and metalloproteinases directed against the implant are seldom presented. This is also true for human osteochondral allografts; few systemic assessments of the immune response exist. More data need to be gathered for both osteochondral allografts and engineered cartilage before one can conclude that non-autologous cells are acceptable.

Are scaffolds required for cartilage synthesis?

In utero, tissue development occurs without exogenous scaffolds; through cell-cell contact, chemical secretion, and, in the case of cartilage, mechanical forces, cells self-organize into differentiated tissues. In vitro, many tissue-engineering strategies have been structured around scaffold design to direct organization and differentiation. For example, collagen sponge, impregnated with hydroxyapatite and BMP-2, is used clinically with success by facilitating MSC colonization and osteogenic differentiation (19). A general consensus regarding scaffold material for bone has been reached (e.g., combinations of collagen, hydroxyapatite, and tri-calcium phosphate), but a large variety of materials are still under assessment for cartilage regeneration (4).

Considerations for scaffold design in cartilage engineering include: 1) Matching biodegradation and growth rates (4). 2) Removing degradation byproducts (e.g., acidic molecules from polymer degradation can provoke degeneration). 3) Removing harsh chemicals involved with scaffold fabrication. 4) Designing scaffolds to maintain spherical chondrocyte morphology and phenotype (20). Most scaffolds, perhaps with the exception of hydrogels, promote cell spreading, encouraging fibrous matrix production (20, 21). 5) Matching scaffold and native cartilage compressive properties may be crucial, as stiff scaffolds shield mechanosensitive cartilage-forming cells from experiencing loading while soft scaffolds may fail upon implantation (22). 6) Scaffolds must possess sufficient surface and tensile properties for functioning in the high shear joint environment. Insufficiencies in these properties result in wear to opposing or adjacent cartilage due to abrasive contact with the articular surface or third body wear from sheared-off scaffold debris. As these considerations are difficult to overcome, it may be suggested that scaffolds be omitted from cartilage engineering.

To mitigate the challenges associated with scaffold use, techniques promoting formation of biomechanically robust neocartilage without using scaffolds have been developed (3). As these techniques allow the cells to take on a rounded morphology, characteristic of the chondrogenic phenotype, scaffoldless techniques were initially used to form small spherical aggregates for studying chondrogenesis. Recent research has expanded the use of scaffoldless techniques to the generation of cartilage constructs. For example, by presenting only non-adherent surfaces to the cells under no exogenous forces other than gravity, self-assembly of chondrocytes is driven by minimization of free energy. Reminiscent of cartilage formation in embryonic development, a cascade of cell-cell and cell-matrix interactions occur resulting in collagen VI localized around chondrocytes and collagen II throughout the neotissue. After 4 weeks, self-assembled neocartilage exhibits gross morphological, histological, biochemical, and biomechanical similarities to native cartilage (23). Studies comparing scaffold-based and scaffoldless approaches illustrate that the latter generate cartilaginous tissues with higher ECM content and mechanical properties (21, 24). Currently, scaffoldless technologies (18, 25) are undergoing clinical trials, and one could argue that scaffoldless methods should be favored.

The challenge of engineering biomechanically suitable cartilage

One of the primary functions of bone and cartilage is to bear load. Cartilage's dense but highly hydrated matrix results in time-dependent response to loads and low friction (3). Mismatches in viscoelastic properties result in strain disparities between neocartilage and adjacent tissue, leading to tissue degradation. Cartilage also needs to withstand shear forces that exist over a large range of motion. Currently, no other materials can simultaneously match cartilage's compressive, friction, and tensile properties under large deformations and motions. In contrast, bone's biomechanical response to loading is not as time-dependent, does not involve articulation, and is more similar to traditional engineering materials, such as porous titanium, that can be fabricated to exhibit bone properties. This enables materials, such as porous hydroxyapatite, to provide initial stability and, following in vivo maturation, recapitulation of bone biomechanical properties. In contrast, evidence exists that cartilage repair techniques, including ACI and microfracture, are unable to replicate the biomechanical properties of native tissue (11, 26).

Cartilage can experience forces up to 6x body weight and stresses approaching 10 MPa (27). Upon loading, cartilage's interstitial fluid is pressurized due to electrostatic and steric interactions that impede water flow (3) and bears the majority of load; the remainder is borne by the ECM. Clinically available cartilage repair techniques do not recreate this structure-function relationship and therefore generate tissues with deficient compressive properties (9-11, 26). Numerous stimuli can enhance neocartilage's compressive properties. For example, temporally-coordinated TGF-β3 and dynamic compression have generated neocartilage possessing compressive properties equivalent to native tissue (28). Thus, while proper compressive properties following microfracture and ACI have been difficult to obtain, tissue-engineering techniques have enabled the in vitro generation of tissues that possess the compressive properties of native tissue.

Cartilage's kinetic coefficient of friction is less than 0.005, besting most man-made bearings by at least an order of magnitude. Without this low frictional property, contact shear results in significant wear. Cartilage garners its nearly frictionless properties from a complex combination of fluid film lubrication (forming a thick fluid film between opposing surfaces), boundary lubrication (forming a thin film of sacrificial molecules), interstitial fluid pressurization (limiting normal loads on opposing ECM), and a migrating contact area (ensuring fluid phase bears the majority of normal loads) (29). Cartilage can be engineered with frictional properties similar to those of native tissue (7, 30); TGF-β1 and shear mechanical stimulation are both effective at lowering the friction coefficient (31, 32). Considering that frictional test parameters have not yet been standardized for cartilage, emphasis needs to be placed not only on engineering low friction properties, but also developing test standards.

As with frictional properties, tensile properties are critical to the success of cartilage tissue-engineering. Although minimized by low friction, cartilage experiences tensile strains 1) during articulation from the drag between opposing surfaces, 2) during compressive loading in areas adjacent to the vicinity of loading, and 3) due to its propensity to swell (3). Cartilage's surface collagen is parallel to the direction of shear to optimize tensile resistance. To anchor cartilage to bone, deep zone collagen is oriented perpendicular to the surface. This highly organized and extensively cross-linked ultrastructure and its concomitant tensile properties have been difficult to recreate in the laboratory. Progress has been made, nonetheless, using remodeling agents (e.g., chondroitinase), TGF-β, and mechanical stimulation for increasing engineered cartilage's tensile modulus values over 3.4 MPa (33-35). To reach native tissue tensile values (5-25 MPa) (3), greater emphases should be placed on enhancing collagen organization, maturation, crosslinking, and content, qualities notoriously deficient in neocartilage. Cartilage mechanical properties, not just histology or biochemistry, must be assessed as part of demonstrating efficacy, as per the FDA's relevant guidance document (36).

Is it possible to integrate engineered and native tissue?

Integration is critical to the success of tissue replacement as it provides stable biologic fixation, load distribution, and also the proper mechanotransduction necessary for homeostasis. Osseointegration to a variety of materials readily occurs and provides stability for metallic implants, collagen scaffolds, and porous ceramics, due to bone's high metabolism and cells, including stem cells (19, 37). Vertical integration of cartilage to underlying bone occurs to a significant extent, however, lateral integration of cartilage to adjacent cartilage is rarely, if ever, reported (38). This challenge is a major stumbling block to the success and commercialization of regenerative strategies and must be addressed to achieve permanent cartilage replacement.

By harnessing the healing capability of bone, cartilage can be integrated into full-thickness defects, reestablishing loading and anchoring neocartilage to underlying bone. By placing neocartilage in direct apposition with bone, a transitional area, histologically similar to the native cartilage-to-bone interface, is recreated (38). However, incidences of delamination suggest that histological appearance is not indicative of a functional interface (39). Thus, tissue-engineers have recently begun to generate osteochondral constructs to ensure that a mechanically stable interface can be created (40). Upon the construct's implantation, it is expected that the osteoinductive ability of the ceramic “bone” will facilitate stable fixation. Overall, vertical integration is driven by bone and not cartilage.

Cartilage-to-cartilage integration is exceedingly difficult to achieve because cartilage displays low metabolism and contains dense, anti-adhesive ECM (41). For example, proteins transcribed from the prg4 gene, contributors to cartilage's low friction, and GAGs have been shown to directly inhibit cell adhesion (42). Further reducing integration potential, surgical preparation of defects results in cell death at defect margins (43). In the clinic, vertical integration can be assessed using MRI, but no imaging techniques exist with sufficient resolution to inform the extent of microscopic lateral integration. Upon loading, mismatches between the biomechanical properties of the cartilage implant and native tissue result in stress concentrations diminishing integration and damaging surrounding tissue (38). Strategies to enhance lateral integration in the laboratory include anti-apoptosis agents to mitigate cell death at the defect edge (43), matrix-degrading enzymes to decrease ECM anti-adhesive properties (41), and, more recently, scaffold functionalization to enable direct bonding to adjacent cartilage (44). Since safety and efficacy of these treatments have yet to be determined, lateral integration remains a significant problem. Additionally, it is conceivable that rehabilitation protocols could be developed to enhance the biomechanical milieu of the interface and, thus, promote lateral integration.

Future of Cartilage Engineering

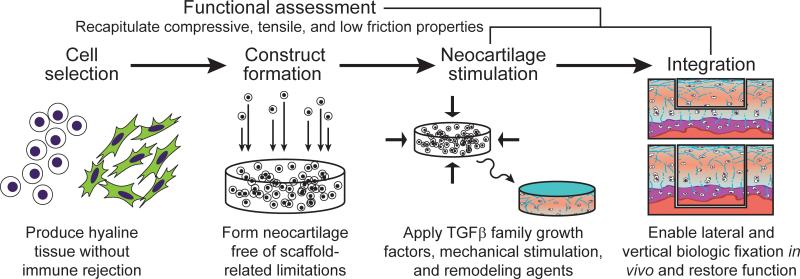

Scaffoldless neocartilage can now be formed with high fidelity to native tissue using expanded chondrocytes and various exogenous stimuli (Fig. 3). Strategies for in vitro vertical integration have been developed, and several candidates for lateral integration appear promising. Adding to existing procedures such as ACI, a plethora of new technologies is under development (Table S1).

Fig. 3.

Scaffoldless tissue-engineering. The cell source chosen for cartilage generation, treated with appropriate culture conditions, must have the ability to produce matrix specific to articular cartilage and must not evoke an immune response. TGF-β family growth factors, physiologic mechanical stimulation, and matrix remodeling enzymes have shown a large degree of promise as stimuli.

Several of these technologies directly address the hurdles of cartilage regeneration: FGF-18 stimulates cartilage growth and decreases cartilage degeneration scores in an osteoarthritis model (45). FGF-2 primes cells for chondrogenesis during in vitro expansion (46). Transfection of chondrocytes to express TGF-β1 enhances cartilage formation (47). Purification using cellular molecular markers associated with high chondrogenic potential enhances the hyaline quality of cartilage formed from expanded chondrocytes (48). Emerging technologies are also harnessing the superior cartilage generating ability of juvenile chondrocytes (18) and co-cultures of primary chondrocytes with MSCs (49). Scaffolds now include biphasic, osteochondral designs that may immediately bear load (50). Scaffoldless approaches also allow for the formation of constructs that can be immediately load-bearing upon implantation (25, 51). Another emerging area involves the functionalizing scaffolds with moieties, such as N-hydroxysuccinimide, that chemically bind to collagen (52). Stimulation during neocartilage formation using mechanical (17), anabolic (47), and, potentially, catabolic stimuli (35) may also be employed. Pathway analysis among diverse classes of stimuli allows for their strategic combination to result in synergistic interactions in cartilage formation.

For FDA approval, new cartilage therapies should show durable repair. However, toughness and hardness, both important for characterizing resistance to wear, are seldom reported, nor have technologies been developed to address these. In addition to mineralization, bone quality has been correlated with the degree of matrix crosslinks (53), but data on cartilage crosslinks in engineered or repair cartilages are currently absent. Associating cartilage durability with such biochemical parameters may deliver new technologies that drive the next phase of cartilage healing: durable repair that prevents the onset of osteoarthritis altogether.

Though currently healing of cartilage defects continues to be elusive, given that emerging technologies are being validated clinically, the field is primed for an explosion of cartilage regeneration techniques that should excite those suffering from cartilage afflictions. Furthermore, while osteoarthritis is currently an intractable problem, exciting new discoveries bode well for the eventual healing of a problem that afflicts a quarter of our adult population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: We gratefully acknowledge support from the National Institute of Health (R01AR053286, R01DE015038, and R01DE019666).

This is the version of the paper accepted for publication by AAAS after changes resulting from peer review, but before AAAS's editing, image quality control, and production. AAAS allows this “accepted version” to be made publicly available six months after final publication. The published paper's full reference citation is: Huey DJ, Hu JC, Athanasiou KA. Unlike bone, cartilage regeneration remains elusive. Science. 2012 Nov 16;338(6109):917-21. The original AAAS published version can be found at: http://www.sciencemag.org/content/338/6109/917.long

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References and Notes

- 1.Langer R, Vacanti JP. Science. 1993 May 14;260:920. doi: 10.1126/science.8493529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Viola J, Lal B, Grad O. National Science Foundation; Arlington, VA: Oct, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Athanasiou KA, Darling EM, Hu JC. Synthesis Lectures on Tissue Engineering. 2009;1:1. 2009/01/01. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Meyer U, Wiesmann HP. Bone and cartilage engineering. Springer; Berlin ; New York: 2006. pp. xiii–264. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams R, et al. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13246. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colnot C. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2011 Dec;17:449. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2011.0243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moutos FT, Guilak F. Tissue Eng Part A. 2010 Apr;16:1291. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2009.0480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee CH, et al. Lancet. 2010 Aug 7;376:440. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mithoefer K, McAdams T, Williams RJ, Kreuz PC, Mandelbaum BR. Am J Sports Med. 2009 Oct;37:2053. doi: 10.1177/0363546508328414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steck E, et al. Stem Cells Dev. 2009 Sep;18:969. doi: 10.1089/scd.2008.0213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gille J, et al. Cartilage. 2010 Jan 1;1:29. doi: 10.1177/1947603509358721. 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen FH, Tuan RS. Arthritis Res Ther. 2008;10:223. doi: 10.1186/ar2514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pelttari K, et al. Arthritis Rheum. 2006 Oct;54:3254. doi: 10.1002/art.22136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Roberts S, Menage J, Sandell LJ, Evans EH, Richardson JB. Knee. 2009 Oct;16:398. doi: 10.1016/j.knee.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bartlett W, et al. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005 May;87:640. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.87B5.15905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zheng MH, et al. Tissue Eng. 2007 Apr;13:737. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.0246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crawford DC, Heveran CM, Cannon WD, Jr., Foo LF, Potter HG. Am J Sports Med. 2009 Jul;37:1334. doi: 10.1177/0363546509333011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adkisson H. D. t., et al. Am J Sports Med. 2010 Jul;38:1324. doi: 10.1177/0363546510361950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.He D, et al. J Neurosurg. 2010 Feb;112:319. doi: 10.3171/2009.1.JNS08976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nuernberger S, et al. Biomaterials. 2011 Feb;32:1032. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.08.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dehne T, Karlsson C, Ringe J, Sittinger M, Lindahl A. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11:R133. doi: 10.1186/ar2800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mouw JK, Connelly JT, Wilson CG, Michael KE, Levenston ME. Stem Cells. 2007 Mar;25:655. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2006-0435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ofek G, et al. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2795. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aufderheide AC, Athanasiou KA. Tissue Eng. 2007 Sep;13:2195. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.0291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schubert T, et al. Int J Mol Med. 2009 Apr;23:455. doi: 10.3892/ijmm_00000151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vasara AI, et al. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005 Apr;233 doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000150567.00022.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brand RA. Iowa Orthop J. 2005;25:82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lima EG, et al. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007 Sep;15:1025. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2007.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McNary SM, Athanasiou KA, Reddi AH. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. Jan;6:2012. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2011.0394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ando W, et al. Biomaterials. 2007 Dec;28:5462. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bian L, et al. Tissue Eng Part A. 2010 May;16:1781. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2009.0482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.DuRaine G, et al. J Orthop Res. 2009 Feb;27:249. doi: 10.1002/jor.20713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Elder BD, Athanasiou KA. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2341. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gemmiti CV, Guldberg RE. Tissue Eng. 2006 Mar;12:469. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Natoli RM, Revell CM, Athanasiou KA. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009 Oct;15:3119. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.U. S. D. o. H. a. H. Services, editor. Rockville, MD: Dec, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mavrogenis AF, Dimitriou R, Parvizi J, Babis GC. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2009 Apr-Jun;9:61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khan IM, Gilbert SJ, Singhrao SK, Duance VC, Archer CW. Eur Cell Mater. 2008;16:26. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v016a04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Niemeyer P, et al. Am J Sports Med. 2008 Nov;36:2091. doi: 10.1177/0363546508322131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scotti C, et al. Biomaterials. 2010 Mar;31:2252. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.11.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van de Breevaart Bravenboer J, et al. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2004;6:R469. doi: 10.1186/ar1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Englert C, et al. Arthritis Rheum. 2005 Apr;52:1091. doi: 10.1002/art.20986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gilbert SJ, et al. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009 Jul;15:1739. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Allon AA, et al. J Biomed Mater Res A. May;21:2012. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.34144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moore EE, et al. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2005 Jul;13:623. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2005.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yayon A, et al. Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery, British. 2006 May 1;88-B:344. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ha CW, Noh MJ, Choi KB, Lee KH. Cytotherapy. 2012 Feb;14:247. doi: 10.3109/14653249.2011.629645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vanlauwe J, et al. Am J Sports Med. Sep;9:2011. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Acharya C, et al. J Cell Physiol. 2012 Jan;227:88. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kon E, et al. Am J Sports Med. 2011 Jun;39:1180. doi: 10.1177/0363546510392711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lewis PB, et al. J Knee Surg. 2009 Jul;22:196. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1247749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang DA, et al. Nat Mater. 2007 May;6:385. doi: 10.1038/nmat1890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vetter U, Weis MA, Morike M, Eanes ED, Eyre DR. J Bone Miner Res. 1993 Feb;8:133. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650080203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.