Abstract

Paramphistomiasis, a trematode infectious disease in ruminants, has been neglected but has recently emerged as an important cause of productivity loss. The small intestine of slaughtered sheep was collected weekly from abattoirs (Kermanshah, Sanandaj, Tabriz and Urmia Slaughterhouses) to monitoring the seasonal occurrence of Paramphistomosis, 2,421 sheep carcasses (743 male (30.69 %) and 1,678 female (69.31 %)) were examined, out of which 0.041 % were positive for Paramphistomum infestation. Furthermore, upon evaluation Paramphistomum termatodes, Gastrothylax crumenifer and Cotylophoron detected as well. Overall, the small intestinal infestation by such parasite was 0.041 % which contained hyperemia, severe congestion and haemorrhage. The highest infection in the sheep infected with Paramphistomum spp. was found during the summer (July to August) (6.7, 2 %) and followed by the autumn seasons (November to October) (3.8, 2.3 %). Microscopic study of the small intestine revealed dilatation of intestinal glands, destruction of superficial glands, replacement of fibrin, diffuse infiltration of inflammatory cells and fibrinonecrotic enteritis. Other changes as congestion hemorrhage and nodules of Ostertagia were observed in total examination of small intestines. According to statistical analysis by SPSS software and Chi square test revealed that there is significant difference between pathologic changes, seasons and ecological situations of the region (p < 0.05). There was no significant difference between age, gender and sample pH of examined sheep (p > 0.05).According to the results of pathologic changes of sheep small intestines, preventive measurements in the area should be taken to decrease the damages, so applying a parasitic control program is recommended.

Keywords: Small intestines, Paramphistomum sheep, Microscopic pathology, Statistical analysis

Introduction

Parasitic diseases are a global problem and considered as a copacetic obstacle in the health and products performance of animals (Horal 2006). Small ruminants are impressed by multifarious gastrointestinal parasites such as nematodes, trematodes and cestodes (Sykes 2004). In this regard, there are many sources of the infections caused by immature samples of the Paramphistomidae family, leading to earnest economic losses and mortality in ruminants (Horak 1989). Gastrointestinal parasite infections are a worldwide problem for small and large animals, Domesticated small ruminants, particularly ovis and goat which are as important sources of protein for many Iranians. In West and North West Iran, because of rainy seasons, appropriate conditions are available for development of many parasites (Abdel Ghani 1998). Paramphistomiasis is caused by widespread infection of the small intestines with immature Paramphistomes. Paramphistomes disport a critical globally role in ruminant diseases (Soulsby 2009), and those normally associated with diseases in ovis were determined to be Paramphistomum (P) cervi, P. microbothridium, P. ichikawai, P. gotoi, P. hibemiae, P. liorchis, P. microbiothriodes and P. scotiae (Urquhart et al. 2008). Cotylophoron cotylophorum, Calicophoron calicophorum, Ceylonocotyle streptocoelium and Gastrothylax crumenifer basically cause anaemia. In necropsy, the visible lesions include muscular atrophy, subcutaneous edema, accumulation of fluid in body cavities, duodenal mucosa superior portion thickening, Bloody mucus in intestinal and sometimes, ulcer and hemorrhage have been recorded in the bowel mucosa. Anorexia, watery diarrhea, submandibular edema (P. cervi was reported for the first time in ovis by Kalantar and Afshar in 1342 in Iran, and it was reported for the first time in goat by Eslami and Feyzi in 1354, and by Bagheri in 1341 in cattle. There are numerous reports of clinical Paramphistomosis in ruminants caused by a variety of species (Boray 2004, 1969; Horak 1989) Singh et al. (1984) demonstrated the progressive changes that occur in experimentally infected goats with P. cervi (Singh et al. 1984).

Mukherjee and Deorani 1962 demonstrated the massive infection of a sheep with amphistomes and the histopathology of parasitized rumen. Nobel 1997 studied histopathology of Paramphistomiasis. Sharma Deorani and Katiyar (1967) studied on the pathogenicity of immature Paramphistomes among ovis and goats (Sharma Deorani and Katiyar 1967). Singh et al. (1984) observed histopathology of the duodenum and rumen during experimental infection with P. cervi (Singh et al. 1984). Srivastava and Shah (1964) reported a study on life history and pathogenicity of Cotylophoron cotylophorum (Srivastava and Shah 1964). The life cycles of Paramphistomes cervi resemble each other in every species, and one kind of snail species plays the role of intermediate host, same as in most trematode biology. Bulinus species snails are considered as their intermediate host. Bulinus syngenes, B. alluaudi in Kenya, B. truncatus in Iraq and Egypt, Planorbis planorbis in Bulgaria, Indoplanorbis exustus in India, P. planorbis, B. contortus and B. truncatus in Italy. Planorbiand anisus vortex in Germany were noted as intermediate hosts for P. cervi (Altaif et al. 1978; Arfaa 1962; Deiana 2001; Dinnik 1998). The purpose of this investigation was to study pathologic changes of Paramphistomum parasite effects in the small intestines of slaughtered sheep in urmia abattoir in North West of Iran.

Materials and methods

Description of the study area

The district West and North West Iran of agro-ecological zone was selected for the present study. Climatically, the study region is subtropical and receives an annual rainfall of about 150–350 mm. The temperature is highest in June, before the onset of monsoon soon season. During summer, the daily maximum temperature exceeds 45 °C and rarely declines below 22 °C. Relative humidity is the lowest during April–May and rises during the monsoon season. One year cycle is divided into four portions; winter (December–February), spring (March–April), summer (May–September) and autumn (October–November). Also; summer includes monsoon season (July–August).

Study population and sampling technique

The study population was different ages and body conditions of sheep, were brought from different parts of the country to the abattoir for meat production. Simple random sampling method was used to select the study units.

Animals

This study was carried out by post-mortem examination on 2,421 sheep carcasses (Ghezel: 866; Herrick: 1,034; Afshari: 374; and Makuei: 147) in an industrial abattoir in Urmia between August 2010 to July 2011 in West Azerbaijan province, in the North-West of Iran. In the abattoir, the sheep were examined 2 days in a week, eight times a month throughout four seasons. The type of ecotype or breed was identified according to phenotypic characteristics (Saadat-Nouri and Siaah-Mansour 1996; Mirza-Aghazadeh 2007), the case history and the managemental types of the flocks. The animals were categorized into four breeds: Ghezel, Makuei, Herrick and Afshari.

Sample collection and histopathological evaluation

A midline incision from the xiphoid cartilage to the inguinal region was made and the rumen and intestines were exposed by cutting through the abdominal and paracostal muscles on either side of the midline incision. The small intestines of each animal slaughtered were separated from the other organs with minimal manipulation. The process was started through the distal end of the jejunum; one metre long small intestinal loops were tied at both ends, cut and placed in labeled plastic containers for fluke recovery. This was followed by the collection of samples of the intestines for histopathological examinations. Antemortem examinations were conducted on apparently healthy sheep. The ages of the animals were determined by the dental formula (Oehme and Prier 1986; Saadat-Nouri and Siaah-Mansour 1996). The small intestine was examined in the postmortem inspection to find out any gross pathological changes (The PH of intestines containing pathologic lesions was measured by PH meter and then intended carcass history was written with a view to age and sex). A tissue specimen was taken from the lesion part of the small intestine. Tissue specimens were fixed in 10 % neutralized formaldehyde and embedded in paraffin wax, sectioned at 4–5 μm, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE) for histopathologic examination. The prepared sections were examined under light microscope; small intestine of sheep was examined for the presence of adult paramphistomes.

Gross pathology

At necropsy the intestinal portions were opened separately and examined for gross pathological lesions before their mucosal surfaces were scraped to remove embedded flukes (Boray 1969). In assessment of the small intestines gross pathology the duodenum, proximal jejunum, distal jejunum and the ileum were demarcated on the basis of their distances from the pylorus. The duodenum constituted the first meter from the pylorus, the proximal jejunum extended for 3 m from the distal end of the duodenum while the distal jejunum extended for 4 m from the distal end of the proximal jejunum. The ileum extended up to the ileocecal junction. A checklist of gross pathological lesions was drawn up based on the severity of abomasal edema, intestinal wall thickening, mucosal corrugation, hyperemia, petechiation and ulceration. The severity of the gross pathological lesions was compared to the different experimental groups.

Data analysis

Using the obtained data, the infestation was estimated by prevalence and mean intensity (total number of a particular parasite species in a host species sample) (Margolis et al. 1982). The Chi square test was applied to measure correlation between the parasitism and season. The data was analyzed using SPSS-11.5 for Windows (evaluation version). In all the analyses, confidence level was held at 95 % and P < 0.05.

Results

Prevalence of seasonal

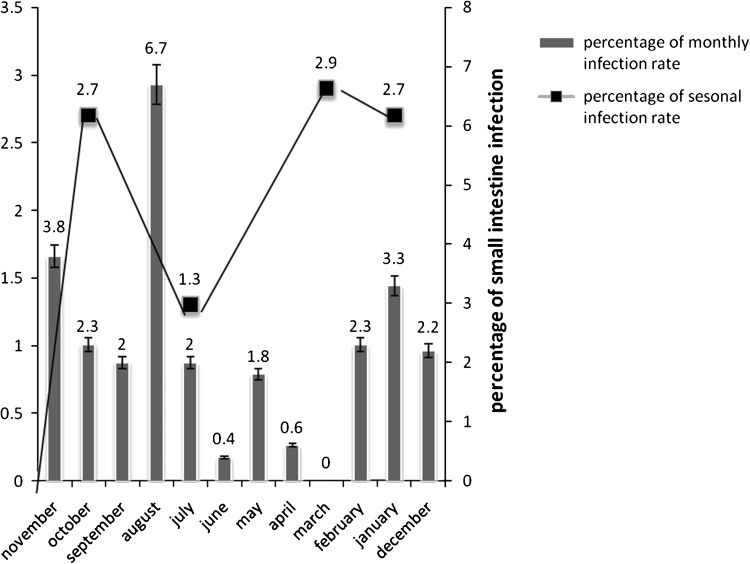

It would be obvious that the highest incidence of Paramphistomosis in sheep was during summer (July to August) with the prevalence rate of 3.3 % that followed by 2.7 % in autumn (October to November), 2.3 % in winter (December to January), and 1.4 % in spring (April to May) (Chi square or likelihood ratio: P < 0.001). The highest positive cases was recorded from March to August with the prevalence rate of 0.0 % in March, 0.6 % in April, 1.8 % in May, 0.4 % in June, 2 % in July and 6.7 % August in sheep (P < 0.001). The lowest prevalence of Paramphistomosis were noted 0 % in March and 0.4 % in June in sheep, (P < 0.001), respectively (Chart 1).

Chart 1.

Diagram of seasonal and monthly infection rate in small intestine samples of 2,421 sheep

Gross pathology findings

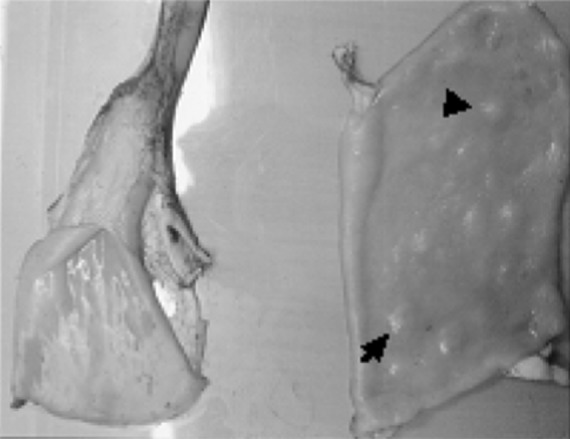

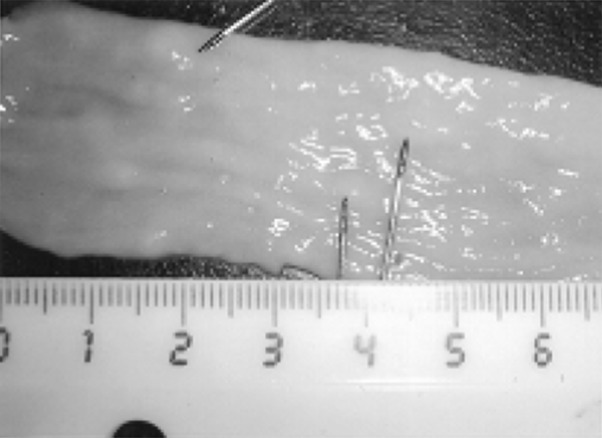

The current study was carried out during 1 year from August 2010 through July 2011 in Urmia abattoir on 2,421 sheep carcasses (743 male and 1,678 female), at 8 months of age through 5 years, and inspected for their intestines. In a survey at Urmia slaughter house ~2,421 sheep carcasses were examined which in 6 cases found ruminal infestation with Paramphistomum (Fig. 1) and only in one case infestation of small intestine was observed, and its pathologic alterations recorded. In general, the lesions were primarily as severe congestion and hemorrhage. It would be obvious that Paramphistomum only observed in 1 sample (0.041 %). The history and features of the mentioned intestines were as; a 2-year-old ewe, intestinal PH = 3.5 with 2 adult Paramohistomum (P. cervi) on duodenal mucosa which had a slight hyperemia. In addition to 148 P. cervi of May ruminal samples, 17 Cotylophoron cotylophorom and 2 Gastrothylax crumenifer observed as well, whereas no lesions detected in small intestines, and over ruminal examination 6 samples of Pramphistomum found which were collected in May (4 samples) and in June (2 samples). Additionally, during the research some other lesions observed in the intestines such as hyperemia, hemorrhage, ulcer, nodular protrusions (Figs. 2, 3, 4) and Ostertagia noduls. Among 2,421 specimens the lesions were as hyperemia 39(1.6 %), hemorrhage 2(0.1 %), ulcer 4(0.2 %), 22(0.9 %) nodular protrusions with different sizes and shapes, and Ostertagia nodules 14(0.541 %). In this study from 242 intestinal samples 85(3.5 %) Ostertagia parasites isolated from both sexes (from 21 intestinal samples) which most of them originated from infested abomasums, whereas in November the samples contained 4 Ostertagia that stemmed from the intestine, and the abomasums were entirely normal without any pathologic lesions or parasites.

Fig. 1.

Ruminal infestation with Paramphistomum

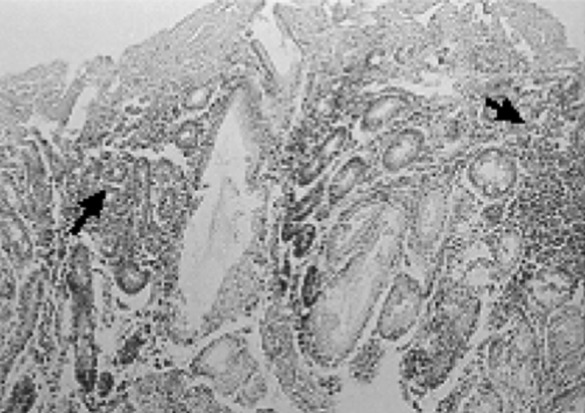

Fig. 2.

Masses or irregular nodules on the wall of the duodenum (arrow)

Fig. 3.

Masses or irregular nodules on the wall of the duodenum (arrow)

Fig. 4.

Ulcer and severe congestion in the duodenum

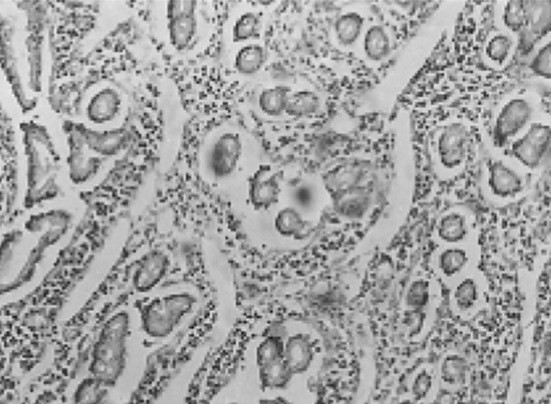

Histopathological findings

In an infested intestine by Paramphistomum some changes as (1) glandular dilatation, glandular superficial destruction, fibrinous fiber replacement, somehow Erythrocytes and inflammatory cells were diagnosable among them. (2) Gland atrophy and diffuse infiltration of lymphocytes and eosinophils around them (Fig. 5). (3) Lymphocytic and eosinophilic diffuse infiltration around glands along with a fibrinous membrane on the intestinal glands (Fig. 6). (4) Relative increase of mucosal cells (Fig. 7) (5) severe infiltration of mononuclear cells and eosinophils among glands (Fig. 8) and superficial destruction along with fibrinous and erythrocytic replacement. (6) Fibrinonecrotic enteritis with diffuse increase of lymphocytes and eosinophils. (7) Diffuse infiltration of lymphocytic and eosinophilic inflammatory cells around glands (Fig. 9).

Fig. 5.

Gland atrophy and diffuse infiltration of inflammatory cells around glands (lymphocytes and eosinophils) around them

Fig. 6.

Lymphocytic and eosinophilic diffuse infiltration around glands along with a fibrinous membrane on the intestinal glands (arrow)

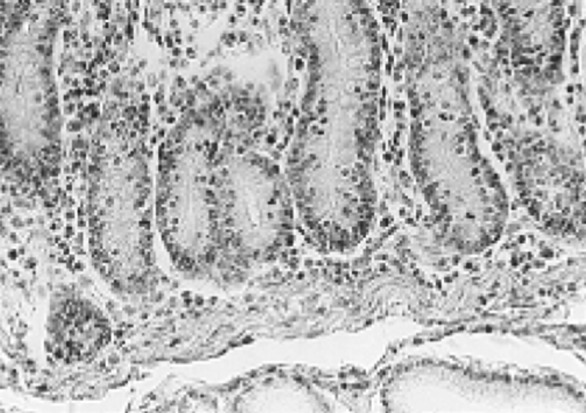

Fig. 7.

The relative increase in mucus-producing cells

Fig. 8.

Severe infiltration of inflammatory cells around glands (arrow)

Fig. 9.

Severe infiltration of inflammatory cells around glands (arrow)

Chi square and SPSS findings

Regarding the effect of season and climatic conditions on Paramphistomum infestation, demonstrated that there is significant difference among lesions, season and climatic changes (P ≤ 0.05). Concerning the PH of specimens revealed that it was 4–5, so the PH had no effect on triggering infestation (P > 0.05). In regard to obtained results no significant difference observed according to sex, age and small intestine (P > 0.05).

Discussion

Paramphistomiasis, a trematode infectious disease in ruminants, has been neglected but has recently emerged as an important cause of productivity loss (Anuracpreeda et al. 2008). The species identification is still neglected as the various species of the family paramphistomatidae are difficult to be detected through a systematic point of view, and most of the reports do not quote the main one (Mage et al. 2002). Paramphistomatidae are the most important trematods of rumen and reticulum in ruminants. They elapse their maturity period in rumen and reticulum and have no changes in these organs and risk for host. But there are larval forms of these trematods in small intestine while generate pathologic changes there. The pathology of amphistome infection has been systematically studied in goats and sheep (Horak and Clark 2000; Singh et al. 1984; Rolfe et al. 1994). In present study, in addition to pathologic lesions of Paramphistomum the prevalence and frequency evaluated as well. The Parasitic frequency was severe in rainy seasons, which detected in rumen, reticulum and small intestine of some sheep in May and June. In previous studies also have reported such results which confirm the prevalence time of the parasite. However, Rolfe et al. (1991) demonstrated that such parasite prevalence in summer and early winter was more than other times (Rolfe et al. 1991). In the present assessment the adult stage of the parasite observed in rumen and intestine, whereas over ruminoreticular examination no pathologic symptoms recorded which represent its immature stage is pathologic for the intestine. Furthermore, in this study found that sex and age have no effect on infestation. In a study by Smith et al. (1999) which evaluated the Paramphistomum prevalence (P. danceti, P. cervi) in cattle showed that sex and age have no role in infestation rate, and most of them were in females (Smith et al. 1999). In a study by Albores-Brahms and Gamboa-Aguilar (2002) on mechanical changes of small intestine, revealed that such alterations originate from immature Pramphistomumcervi, and mucosal and ulcerative hemorrhages occurred that is in agreement with the present research (Albores-Brahms and Gamboa-Aguilar 2002). Pathogenic effect of Paramphistomosis depends on the number of parasites in the animals. In experimental Paramphistomosis induced with P. ichikawai in lambs, severe destruction associated with increased infiltration of eosinophils was observable in the mucosa of rumen. In the same study, it is recommended that the presence of 20,000–25,000 flukes would result in clinical disease; smaller numbers would cause significant subclinical disease (Rolfe et al. 1994). Most infections of adult fluke are harmless although large number of flukes can cause a chronic ulcerative rumenitis with ruminal papillae atrophy (Love and Hutchinson 2003).The immature forms of P. cervi caused more severe damage in the duodenal tissue, whereas the mature form inflicted mild tissue damage in the rumen of the experimental kids. In present study, prevalence of Paramphistomosis in sheep was at 0.2 % average yearly, somehow throughout a year was between 0 and 2.4 %, which is much lesser than that recorded in Heilongjiang Province in People’s Republic of China (Wang et al. 2006), in Maiduguri in Nigeria (Biu and Oluwafunimilayo 2004), is similar to Himalayan region of India (Tariq et al. 2008) and to that found in the Fars province of Iran (Moghaddar and Khanitapeh 2003). The highest prevalence of Paramphistomum spp. in ovis in the summer and autumn seasons is in agreement with the observations of other researchers. Rangel-Ruiz et al. (2003) from Tabasco, Mexico reported that the sheep primarily were affected throughout the rainy and windy seasons, during summer, autumn and in the beginning of the winter (Rangel-Ruiz et al. 2003). Tariq et al. (2008) reported that highest ovis infection was in summer and the lowest in winter. In the North West temperate of Himalayan area of India a similar study demonstrated the severity and intensity of infection, reaching to its maximum in late summer and autumn season in drier months. They also emphasize that the low prevalence in winter could be attributed to harsh snowy winter conditions during which the whole valley remains snow covered and there are no chances of fresh infection due to non-availability of intermediate snail hosts (Tariq et al. 2008). The lowest prevalence in winter (November to December) with the prevalence rate of 0.49 % and highest prevalence during monsoon and post-monsoon (July to October) (8.06 %) followed by in summer (March to June) (2.92 %), were recorded in domestic ruminants as well by Hassan et al. (2005) (Hassan et al. 2005). Furthermore, similar prevalence of Paramphistomum in ovis to the present research was recorded with prevalence of 28.57 % in Pakistan and Njoku-Tony and Nwoko (2009) who recorded 26.2 % prevalence. Higher prevalence of Paramphistomum in sheep was recorded by Manna et al. (1994) in India (55.9 %) (Manna et al. 1994). Lower prevalence was recorded by Mogdy et al. (2009) in Egypt (7.06 %) (Mogdy et al. 2009). It would be apparent that different prevalence of Paramphistomum in the reports could be explained either by the different parasitological techniques used in these studies, and differences of the samples originated from geographical differences. Other factor which attributes for such difference may be due to suitable ecological factors for the snail intermediate host of Paramphistomum in these zones.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank staff of the Department of pathology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Urmia University for their valuable technical assistance.

References

- Abdel Ghani AF. The cercariae and the metacercaria of Paramphistomum cervi. Agric Res Rev Cairo. 1998;38:237–243. [Google Scholar]

- Albores-Brahms ST, Gamboa-Aguilar J. Seasonal trends of Paramphistomum cervi in Tabasco, Mexico. Vet Parasitol. 2002;116:217–222. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2003.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altaif KI, Al-Abbassy SN, Al-Saqur IM, Jawad AK. Experimental studies on the suitability of aquatic snails as intermediate hosts for Paramphistomum cervi in Iraq. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1978;72:151–155. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1978.11719297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anuracpreeda P, Wanichanon C, Sobhon P. Paramphistomum cervi antigenic profile adults as recognized by infected cattle sera. Exp Parasitol. 2008;118:203–207. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arfaa F. A study on Paramphistomum microbothrium in Khuzistan S. W. Iran. Annls Parasitol Hum Comp. 1962;37:519–555. doi: 10.1051/parasite/1962374549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biu AA, Oluwafunimilayo A. Identification of some Paramphistomes infecting sheep in Maiduguri, Nigeria. Pak Vet J. 2004;24(4):187–189. [Google Scholar]

- Boray JC. The anthelmintic efficiency of niclosamide and menichlopholan in the treatment of intestinal Paramphistomosis in sheep. Aust Vet J. 1969;45:133–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1969.tb01905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boray JC. Studies on intestinal Paramphistomosis in cattle. Aust Vet J. 2004;35:282–287. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-0813.1959.tb08480.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deiana S. L’infestione del Bulinus contortus ‘da cercarie dischistosoma bovis (Sonsino, 1876) e Del Paramphistomıım an’i (Schrank, 1790) in diverse stagionidell’ anno. Biol Sper. 2001;5:1939–1940. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinnik JA. An intermediate host of the. Common.s.tomaclz fluke, Paramphistomum cervi (Schmnk), in Kenya. East Afr Agric J. 1998;26:124–125. [Google Scholar]

- Hassan SS, Kaur K, Joshi K, Juyal PD. Epidemiology of Paramphistomosis in domestic ruminants in different districts of Punjab and other adjoining areas. J Vet Parasitol. 2005;19(1):43–46. [Google Scholar]

- Horak IG. Paramphistomiasis of domestic ruminants. Adv Parasitol. 1989;9:33–72. doi: 10.1016/S0065-308X(08)60159-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horak IG, Clark R. Studies on Paramphistomiasis. V. The pathological physiology of the acute disease in sheep. Onderstepoort J Vet Res. 2000;30:145–160. [Google Scholar]

- Horal IG. Paramphisomiasis of domestic ruminants. In: Dawes B, editor. Advance in parasitology. New York: Academic Press; 2006. pp. 33–70. [Google Scholar]

- Love SCJ, Hutchinson GW (2003) Pathology and diagnosis of internal parasites in ruminants. In: Gross pathology of ruminants, Proceedings 350, Post Graduate Foundation in Veterinary Science, University of Sydney, Sydney, Chapter 16, pp 309–338

- Mage C, Bourgne H, Toullieu JM, Rondelaud G. Fasciolahepatica and Paramphistomum daubneyi: changes in the prevalence of natural infections in cattle and Lymnaea truncatula from Central France over the past 12 years. Vet Res. 2002;33:439–447. doi: 10.1051/vetres:2002030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manna AS, Prmanik G, Mukherjee S. Incidence of paramphistomiasis in West Bengal. Indian J Anim Health. 1994;33:87–89. [Google Scholar]

- Margolis L, Esch GW, Holmes JC, Kuris A, Mschad GA. The use of ecological terms in parasitology (report of an adhoc committee of the American Society of Parasitologists. J Parasitol. 1982;68:131–133. doi: 10.2307/3281335. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mirza-Aghazadeh A (2007) A research in Herrick sheep agricultural system in West Azerbaijan Province, No. 1338, Report of National Research Program, Agricultural Commission (In Persian), pp 90–127

- Mogdy H, Al-Gaabary T, Salama A, Osman A, Amera G. Studies on Paramphistomiasis in ruminants in Kafrelsheikh. J Vet Med. 2009;10:116–136. [Google Scholar]

- Moghaddar N, Khanitapeh N. Prevalence of Paramphistomes in sheep and goat in the Fars province of Iran. Iran J Vet Res. 2003;4(2):166–170. [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee RP, Deorani SVP. Massive infection of a sheep with Amphistomes and the histopathology parasited rumen. Indian Vet J. 1962;39:668–670. [Google Scholar]

- Njoku-Tony R, Nwoko B. Prevalence of Paramphistomiasis among sheep slaughtered in some selected abattoirs in IMO state, Nigeria. Sci World J. 2009;4:12–15. [Google Scholar]

- Nobel TA. Histopathology of Paramphistomiasis. Ref Vet. 1997;13:155–157. [Google Scholar]

- Oehme WF, Prier EJ. Text book of large animal surgery. 3. London: Williams and Welkins Company; 1986. pp. 451–459. [Google Scholar]

- Rangel-Ruiz LJ, Albores-Brahms ST, G amboa-Aguilar J. Seasonal trends of Paramphistomum cevri in Tabasco, Mexico. Vet Parasitol. 2003;116:217–222. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2003.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolfe PF, Boray JC, Nicholis P, Collins GH. Epidemiology of Paramphistomosis in cattle. Int J Parasitol. 1991;21:813–819. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(91)90150-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolfe F, Boray JC, Collinis GH. Pathology of infection with Paramphistomum ichikawai in sheep. Int J Parasitol. 1994;24:995–1004. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(94)90165-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saadat-Nouri M, Siaah-Mansour S. Sheep Husbandry. 7. Tehran (In Persian): Ashrafi Press; 1996. pp. 70–105. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma Deorani VP, Katiyar RD. Studies on the pathogenicity due to immature Amphistomes among sheep and goats. Indian Vet J. 1967;44:199–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh RP, Sahai BN, Jha GJ. Histopathology of the duodenum and rumen during experimental infections with Paramphistomum cervi. Vet Parasitol. 1984;15:39–46. doi: 10.1016/0304-4017(84)90108-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JH, Reynolds ES, Lichttenberg F. Prevalence of Paramphistomum in cattle. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;18:28–49. [Google Scholar]

- Soulsby EJL. Helm in the Arthropod and Protozoa of domestic animals. 7. London: Bailliere Tindall; 2009. p. 809. [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava HOP, Shah HL. Studies on helminth parasites of desi pigs in Madhya Pradesh. Indian Vet J. 1964;37:698–699. [Google Scholar]

- Sykes AR. The effect of subclinical parasitism in sheep. Vet Res. 2004;102:32–34. doi: 10.1136/vr.102.2.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tariq KA, Chishti MZ, Ahmad F, Shawl WL. The epidemiology of Paramphistomosis of sheep (Ovis aries L.) in the North West temperate Himalayan region of India. Vet Res Commun. 2008;32:383–391. doi: 10.1007/s11259-008-9046-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urquhart GM, Armour J, Duncan JL, Dunn AM, Jennings FW. Veterinary parasitology. 2. Oxford: Long man Scientific and Technical Press; 2008. pp. 100–109. [Google Scholar]

- Wang CR, Qiu JH, Zhu XQ, Han XH. Survey of helminthes in adult sheep in Heilongjiang Province, People’s Republic of China. Vet Parasitol. 2006;140:378–382. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]