Abstract

In this study prevalence of chicken coccidiosis in Jammu division were undertaken in both organized and backyard chickens during the year 2010–2011, with an overall prevalence of 39.58 % on examination of 720 faecal samples. Five Eimeria species were identified viz., E. tenella, E. necatrix, E. maxima, E. acervulina and E. mitis. E. tenella was the predominant species in both organized and unorganized farms. The highest prevalence percentage was found in July, 2011 (68.9 %) and the lowest percentage was found in May, 2011 (12.5 %). Coccidial prevalence was found to be 53.61 % in unorganized (backyard poultry birds) as compared to organized birds (25.55 %). Maximum positive cases of coccidian infection was found in monsoon season (60.55 %) and least in summer season (21.66 %). Birds of age 31–45 days showed more prevalence percentage (58.86 %). Higher oocysts count was recorded from July to September with a peak value (38973.00 ± 3075.6) in July and lowest (12914.00 ± 595.48) in the month of May.

Keywords: Poultry, Coccidiosis, Prevalence

Introduction

Coccidiosis is recognized as the parasitic disease with the greatest economic impact on poultry industries worldwide (Allen and Fetterer 2002) due to production losses and costs for treatment or prevention (Shirley et al. 2005). It is caused by single-celled protozoan parasites of the genus Eimeria, which are commonly referred to as coccidian (McDougald and Reid 1997). The disease is manifested clinically by intestinal haemorrhage, malabsorption, diarrhoea, reduction of body weight gain due to inefficient feed utilization, impaired growth rate in broilers and reduced egg production in layers (Lillehoj and Lillehoj 2000, Lillehoj et al. 2004). Seven species of Eimeria with different degrees of pathogenicity are recognized viz. E. acervulina, E. brunetti, E. maxima, E. mitis, E. necatrix, E. praecox and E. tenella. Eimeria tenella is one of the most ubiquitous (Quarzane et al. 1998) and most pathogenic (Arakawa and Xie 1993; Yadav and Gupta 2001, Ayaz et al. 2003) resulting in 100 % morbidity and a high mortality due to extensive damage of the digestive tract (Cook 1988). The lesions caused by this parasite disturb nutrient absorption, triggering several changes in carbohydrates, lipid, protein and macro and trace mineral metabolism (Witlock et al. 1977). The incidence of coccidiosis in commercial poultry can range from 5 to 70 % (Du and Hu 2004). The Jammu and Kashmir state is no more exception to this as the poultry population has increased from 2.039 million in 2003 to 3.48 million in 2007 (Livestock Census 2007). Growth of poultry industry in India is hampered by various factors and prevalence of various diseases in poultry is of main concern. Among the various parasitic diseases, coccidiosis is one of important concern in poultry sector caused by multiple species of parasite of the genus Eimeria which resides and multiplies in intestinal mucosa (Hadipour et al. 2011). Though, coccidiosis is widely prevalent in Jammu and Kashmir, but very little published information is available. Therefore, present study was conducted to know the prevalence of coccidiosis in Poultry maintained under different managemental conditions in Jammu region of Jammu and Kashmir State, India.

Materials and methods

Poultry birds maintained under two managemental conditions viz. organized and unorganized (backyard poultry birds) were used in this study. A total of 720 faecal samples were collected from organised farms and backyard poultry (unorganised) of Jammu. The faecal samples were collected directly from floors of backyard poultry and commercial farms and stored in plastic containers. The particulars like age, farm management practices were recorded. The samples were kept at 4 °C till examination. The oocysts were concentrated for examination by centrifugation with saturated sugar solution and were identified on the basis of morphological characters. The oocysts recovered were kept in two lots of 2.5 % potassium dichromate solution (K2Cr2O7). The material of one lot was poured in petri dishes to a depth of 3–4 mm and kept in biological oxygen demand (BOD) incubator at a temperature of 30 ± 2 °C for sporulation. The other lot of culture was kept at 4 °C. The culture of both the lots was examined and morphological characters were studied before and after sporulation (Lima 1979; Levine 1985; Pellérdy 1974; Soulsby 1982).

Results

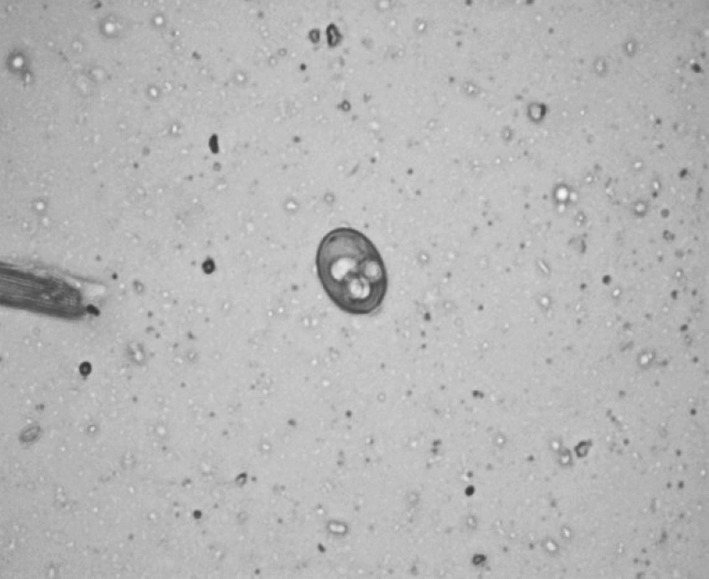

Out of 720 samples examined, 285 were found positive for Eimeria species with an overall prevalence of 39.58 %. Five species of Eimeria viz., E. tenella, E. necatrix, E. maxima, E. acervulina, and E. mitisi were recorded with incidence of 21.40, 11.92, 5.61, 4.21 and 2.10 %, respectively. Eimeria tenella was predominant species infecting chickens in both organized farms as well as backyard chickens of Jammu region. The morphological characteristics of the sporulated oocysts are shown in Plate 1, 2, 3, 4, 5.

Plate 1.

Eimeria tenella

Plate 2.

Eimeria necatrix

Plate 3.

Eimeria maxima

Plate 4.

Eimeria acervulina

Plate 5.

Eimeria mitis

Age of chickens is considered as major factor in the prevalence of Eimeria infection. In the present study, prevalence of coccidiosis was recorded higher in chickens of age group 31–45 days (58.86 %) followed by 16–30 days (49.27 %), 46–60 days (39.87 %), 61–75 days (25.67 %) and lower in 0–15 days (19.49 %) (Table 1; Fig. 1). Prevalence of coccidiosis in chickens was highest (60.55 %) in monsoon (July–September) and lowest (21.66 %) in summer (March–June) (Table 2; Fig. 2). Higher oocysts count was recorded from July to September with a peak value (38973.00 ± 3075.6) in July and lowest (12914.00 ± 595.48) in the month of May (Table 3; Fig. 3).

Table 1.

Age-wise prevalence of chicken coccidiosis in Jammu region

| S. no. | Age group (days) | No. of samples examined (720) | No. of positive samples (285) | Percentage of infection |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 0–15 | 118 | 23 | 19.49 |

| 2. | 16–30 | 138 | 68 | 49.27 |

| 3. | 31–45 | 158 | 93 | 58.86 |

| 4. | 46–60 | 158 | 63 | 39.87 |

| 5. | 61–75 | 148 | 38 | 25.67 |

Figures in parenthesis are %

Bold signifies as higher prevalence (58.86 %) of coccidiosis in the age group of 31–45 days and lowest (19.49 %) in the age group of 0–15 days

Fig. 1.

Age-wise occurrence of Eimeria species in chickens in Jammu region

Table 2.

Season-wise prevalence of chicken coccidiosis in Jammu region

| Season | No. of samples examined | No. of samples Positive | Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Winter (Dec–Feb) | 180 | 55 | 30.55 |

| Summer (Mar–June) | 180 | 39 | 21.66 |

| Monsoon (July–Sep) | 180 | 109 | 60.55 |

| Post monsoon (Oct–Nov) | 180 | 82 | 45.55 |

Figures in parenthesis are %

Bold signifies as higher prevalence (60.55 %) of coccidiosis in Monsoon and lowest (21.66 %) in Summer season

Fig. 2.

Season-wise prevalence of chicken coccidiosis in Jammu region

Table 3.

Month-wise variation in the (mean ± SE) OPG values of chicken coccidiosis

| Months (2010–2011) | Mean values ± SE |

|---|---|

| December | 25651.90 ± 1478.2e |

| January | 16950.47 ± 414.83c |

| February | 15477.12 ± 661.29c |

| March | 13793.66 ± 395.61ab |

| April | 14510.10 ± 736.00b |

| May | 12914.00 ± 595.48 a |

| June | 19077.86 ± 749.88d |

| July | 38973.00 ± 3075.6 g |

| August | 38740.18 ± 2675.7g |

| September | 38037.18 ± 1489.7g |

| October | 31958.20 ± 789.54f |

| November | 27650.02 ± 1457.6e |

Mean (±SE) bearing different superscripts differ significantly (P < 0.05)

Bold signifies higher oocysts count with a peak value was recorded in the month of July (38973.00 ± 3075.6) and lowest in the month of May (12914.00 ± 595.48)

Fig. 3.

Month-wise variation (mean ± SE) in the OPG values in chicken coccidiosis

Discussion and conclusion

In the present study, the overall prevalence of coccidiosis in Jammu region was found to be 39.58 %. The present observation is comparable with that of 33.33 % coccidian infection found in studies conducted by Sood et al. (2009) from Jammu, 46.04 % Jadhav et al. (2011) in Aurangabad district of Maharashtra and 31.25 % coccidian infection found by Bandyopadhyay et al. (2006) in West Bengal.

Eimeria tenella was predominant species infecting chickens in both organized farms as well as backyard chickens of Jammu region. The present findings are in agreement with the findings of Bhaskaran et al. (2009). However involvement of E. tenella in many outbreaks has also been documented from other parts of India (Jithendran 2001; Aarthi et al. 2010; Jadhav et al. 2011).

Higher prevalence of coccidiosis in the age group of 31–45 days might be associated with the presence of high number of oocysts in the litter. A possible reason for this may be that during the period between 31 and 45 days of age the birds have not attained immunity against coccidiosis, resulting in the increased incidence of the disease, while as the birds of age group 0–15 days were protected by the maternal immunity. Similar findings of high prevalence of coccidiosis in chickens of age group ranging from 31 to 45 days has been reported by several workers (Lobago et al. 2003; Kumar et al. 2008; Adhikari et al. 2008; Nematollahi et al. 2009).

Prevalence of coccidiosis in chickens was highest in monsoon and lowest in summer. The present finding is in commensuration of Jithendran 2001; Hirani et al. 2011. Higher prevalence in monsoon period could be attributed to increase in rainfall with subsequent high humidity and drop in temperature which is conducive for sporulation of oocysts for easy dispersion and transmission. The occurrence of coccidiosis was more in backyard chickens than in organized farms. In the present study, percentage prevalence malnutrition and non-use of coccidiostats as preventive measures. The warmth and moisture in such environment favours greater transmission and contamination of oocysts. However, the higher prevalence rate of coccidiosis during the rainy season also agrees with earlier reports of Oluyemi and Roberts 1979; Halle et al. 1998; Alawa et al. 2001).

Higher oocysts count was recorded from July to September with a peak value in July and lowest in the month of May. This observation correlates with the fact that sporulation of coccidian oocysts requires moisture and optimum temperature of 30 °C (Pellérdy 1974). It was observed that the temperature of the study area was above 35 °C in summer months with a relative low humidity which is unfavourable for development of oocysts. On the other hand, oocyst count increased in monsoon when rainfall renders humidity and temperature conducive for sporulation of oocysts. These observations are in agreement with those of Sisodia et al. (1997) and Senthilvel et al. (2004) who reported a similar pattern of intensity of Eimeria species at Rajasthan and Tamil Nadu, respectively.

Analysis according to age groups showed that the spread of infection increased with age, peaking in 31–45 days and diminishing afterwards. The OPG ratio also increased with age, with a peak in 31–45 days and a definite decrease after that. The results are in agreement with the studies of Karaer et al. (2011) who reported the peak OPG values in 31–40 days age group in broiler farms in Turkey. A possible reason for this may be that during the period between 31 and 45 days of age the birds have not attained immunity against coccidiosis, resulting in the increased incidence of the disease.

The present findings on the prevalence and species spectrum of chicken coccidiosis in Jammu region are of much significance from the economic and pathological point of view as very little or no documented information is available on these aspects.

Acknowledgments

The authors thanks to the Dean, FVSc and A.H., R.S. Pura Jammu for providing necessary facilities at time of research.

References

- Aarthi S, Raj GD, Gaman M, Gomathinayam G, Kumanan K. Molecular prevalence and preponderance of Eimeria species among chicken in Tamil Naidu, India. Parasitol Res. 2010;107(4):1013–1017. doi: 10.1007/s00436-010-1971-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adhikari A, Gupta R, Pant GR. Prevalence and identification of coccidian parasite in layer chicken of Ratnanagar municipality, Chitwan district, Nepal. J Nat Hist Mus. 2008;23(7):45–50. [Google Scholar]

- Alawa CBI, Mohammed AK, Oni OO, Adeyinka IA, Lamidi OS, Adam AM. Prevalence and seasonality of common health problems in Sokoto Gudali cattle at a beef research station in the Sudan ecological zone of Nigeria. Niger J Anim Prod. 2001;28:224–228. [Google Scholar]

- Allen PC, Fetterer RH. Recent advances in biology and immunobiology of Eimeria species and in diagnosis and control of infection with these coccidian parasites of poultry. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2002;15:58–65. doi: 10.1128/CMR.15.1.58-65.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arakawa A, Xie MQ. Control of coccidiosis in chicken. J Protozool Res. 1993;3:31–39. [Google Scholar]

- Ayaz M, Akhtar M, Hayat CS, Hafeez MA, Haq A. Prevalence of coccidiosis in broiler chickens in Faisalabad, Pakistan. Pak Vet J. 2003;23:51–52. [Google Scholar]

- Bandyopadhyay PK, Bhakta JN, Shukla R. Eimeria indiana (Apicomplexa, Sporozoea), a new Eimerian species from the hen, Gallus gallusdomesticus (Aves, Phasianidae) in India. Protistology. 2006;4(3):203–206. [Google Scholar]

- Bhaskaran MS, Venkatesan L, Aadimoolam R, Jayagopal HT, Sriraman R. Sequence diversity of internal transcribed spacer-1 (ITS-1) region of Eimeria infecting chicken and its relevance in species identification from Indian field samples. Parasitol Res. 2009;106(2):513–521. doi: 10.1007/s00436-009-1696-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook GC. Small intestinal coccidiosis: an emergent clinical problem. J Infect. 1988;16:213–219. doi: 10.1016/S0163-4453(88)97484-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du A, Hu S. Effects of a herbal complex against Eimeria tenella infection in chickens. J Vet Med. 2004;51(4):194–197. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0450.2004.00749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadipour MM, Olyaie A, Naderi M, Azad F, Nekouie O. Prevalence of Eimeria species in scavenging native chickens of Shiraz, Iran. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2011;5:3296–3299. [Google Scholar]

- Halle PD, Umoh JU, Saidu L, Abdu PA. Diseases of poultry in Zaria, Nigeria: a ten-year analysis of clinical records. Niger J Anim Prod. 1998;25:88–92. [Google Scholar]

- Hirani ND, Hasnani JJ, Veer S, Patel PV, Dhami AJ. Epidemiological and clinic-pathological studies in Gujarat. J Vet Parasitol. 2011;25(1):42–45. [Google Scholar]

- Jadhav BN, Nikam SV, Bhamre SN, Jaid EL. Study of Eimeria necatrix in broiler chicken from Aurangabad district of Maharashtra state India. Int Multidiscip Res J. 2011;1(11):11–12. [Google Scholar]

- Jithendran KP. Coccidiosis—an important disease among poultry in Himachal Pradesh. ENVIS Bull Himal Ecol Dev. 2001;9(2):1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Karaer Z, Guven E, Akcay A, Kar S, Nalbantoglu S, Cakmak A. Prevalence of subclinical coccidiosis in broiler farms in Turkey. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2011;10(9):29–33. doi: 10.1007/s11250-011-9940-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Gabhane G, Gogoi D, Raut B. Coccidiosis in broilers: an outbreak in cold desert region. J Vet Parasitol. 2008;22(1):61–62. [Google Scholar]

- Levine ND. Veterinary protozoology. Ames: Iowa State University Press; 1985. p. 414. [Google Scholar]

- Lillehoj HS, Lillehoj EP. Avian coccidiosis. A review of acquired intestinal immunity and vaccination strategies. Avian Dis. 2000;44:408–425. doi: 10.2307/1592556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillehoj HS, Min W, Dalloul RA. Recent progress on the cytokine regulation of intestinal immune responses to Eimeria. Poult Sci. 2004;83:611–662. doi: 10.1093/ps/83.4.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima JD. Eimeria caprina sp. from the domestic goat (Capra hircus) from the United States of America. J Parasitol. 1979;65(6):902–903. doi: 10.2307/3280246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livestock Census (2007) Ministry of Agriculture and Dairing, Government of India

- Lobago F, Worku N, Wossene A. Study on coccidiosis in Kombolcha poultry farm, Ethiopia. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2003;37(3):245–251. doi: 10.1023/B:TROP.0000049302.72937.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDougald LR, Reid WM. Coccidiosis. In: Calnek BW, Barnes HJ, Beard CW, McDonald LR, Saif YM, editors. Diseases of poultry. 10. Ames: Iowa State University Press; 1997. pp. 865–883. [Google Scholar]

- Nematollahi A, Moghaddam GH, Pourabad RF. Prevalence of Eimeriaspecies among broiler chicks in Tabriz (Northwest of Iran) Munis Entomol Zoolog. 2009;4(1):53. [Google Scholar]

- Oluyemi JA, Roberts FA. Poultry production in warm wet climate. J Anim Prod. 1979;29:301–311. [Google Scholar]

- Pellérdy LP. Coccidia and coccidiosis. 2. Berlin: Paul Parey; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Quarzane M, Labbe M, Pery P. Eimeria tenella: cloning and characterization of cDNA encoding a S3a ribosomal protein. Gene. 1998;225:125–130. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(98)00523-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senthilvel K, Basith SA, Rajavelu G. Caprine coccidiosis in Chennai and Kancheepuram districts of Tamil Nadu. J Vet Parasitol. 2004;18(2):159–161. [Google Scholar]

- Shirley MW, Smith AL, Tomley FM. The biology of avian Eimeria with an emphasis on their control by vaccination. Adv Parasitol. 2005;60:285–330. doi: 10.1016/S0065-308X(05)60005-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sisodia SL, Pathak KML, Kapoor M, Chauhan PPS. Prevalence and seasonal variation in Eimeria infection in sheep in Western Rajasthan. J Vet Parasitol. 1997;11:95–98. [Google Scholar]

- Sood S, Yadav A, Vohra S, Katoch R, Ahmad BD, Borkatari S. Prevalence of coccidiosis in poultry birds in R.S. Pura region, Jammu. Vet Pract. 2009;10(1):69–70. [Google Scholar]

- Soulsby EJL. Helminths, arthropods and protozoa of domesticated animals. 8. London: English Language Book Society and Bailliere Tindal; 1982. p. 809. [Google Scholar]

- Witlock DR, Danforth HD, Ruff MD. Scanning electron microscopy of Eimeria tenella infection and subsequent repair in chicken caeca. J Comp Pathol. 1977;85:571–581. doi: 10.1016/0021-9975(75)90124-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yadav A, Gupta SK. Study of resistance against some ionophores in Eimeria tenella field isolates. Vet Parasitol. 2001;102(1–2):69–75. doi: 10.1016/S0304-4017(01)00512-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]