Abstract

Osteosarcoma (osteogenic sarcoma: OS) is the most common primary malignant bone tumor of long bones, whereas primary osteosarcoma of chest wall, especially in sternum, is extremely rare. We report a 57-year-old man with an immobile slow growing mass located in the middle of the sternum. The patient had no significant pain or tenderness and the past medical history was not remarkable. CT-scan showed a large densely sclerotic sternal mass and MRI revealed an extensive central signal loss within the tumor because of necrosis. We performed a CT-guided needle biopsy, but it was inconclusive. After an incisional biopsy, a high-grade osteosarcoma of the sternum was diagnosed. The patient underwent subtotal sternal resection and reconstruction using synthetic mesh and bone cement followed by chemotherapy and external beam radiotherapy. After one year of follow-up, the patient is back to normal life and is doing the daily activities without problem. By this time, focal recurrence or metastatic disease did not occur.

Key words: Chest wall tumor, Osteosarcoma, Sternum

Introduction

Osteosarcoma (osteogenic sarcoma: OS) is the most common primary malignant bone tumor occurs more commonly in long bones of children and adolescents (1, 2). Occurrence of osteosarcoma in the chest wall, especially in the sternum, is extremely rare, with a reported median age of 42 years at the time of diagnosis (3-5). Malignant sternal tumors usually present with pain and swelling while there may be a history of previous radiation therapy in some patients (6).

Frontal and lateral plain radiographs of sternum have a limited role in diagnosis of sternal osteosarcoma. The modality of choice in assessing sternal masses is the computed tomography (CT) scanning (7). It can show the lesion together with its intrathoracic component. MRI has a complementary role in evaluating the extra-osseous spread of the tumor and its condition in respect to the surrounding structures. MRI is useful in planning for surgical treatment (8). True-cut needle biopsy under imaging guidance may be used for the diagnosis, but open biopsy is considered the most appropriate approach to obtain sufficient material for full histological evaluation (1, 2).

In this report, we explain the clinical presentation and imaging findings of a patient with sternal OS based on our experience.

Case presentation

A 57-year-old man was referred to our hospital with a painless slow growing mass in the middle part of the sternum since 3 month ago. He had no complaint of dyspnea or cough. He also had no history of previous chest surgery, radiotherapy, infection such as tuberculosis, and malignancy. On physical examination, the mass was about 4x5 cm, quite firm, immobile, with no significant pain or tenderness in palpation. The skin over the lesion was normal. There was no palpable lymph node in the supraclavicular and axillary areas. Other organ examinations were normal.

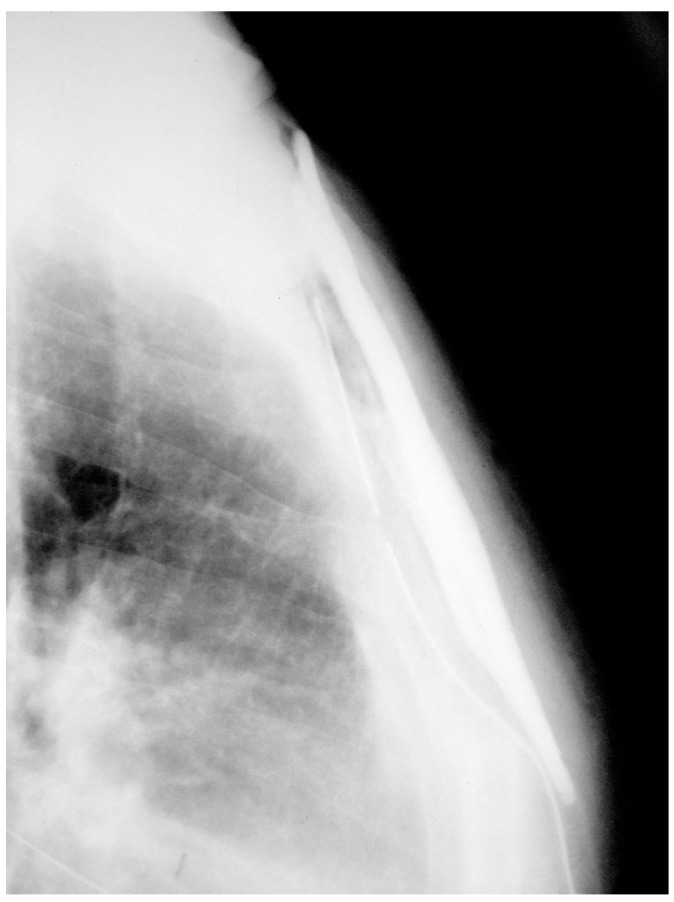

The laboratory studies including complete blood count test, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive Proteins (CRP) were within the normal range. Plain radiographs, demonstrated a large mass in the middle part of the sternum extending to both anterior and posterior surrounding structures [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Chest X-ray (lateral view) showing a large mass in middle part of the sternum, which extending to the overlying ventral and dorsal surrounding structures.

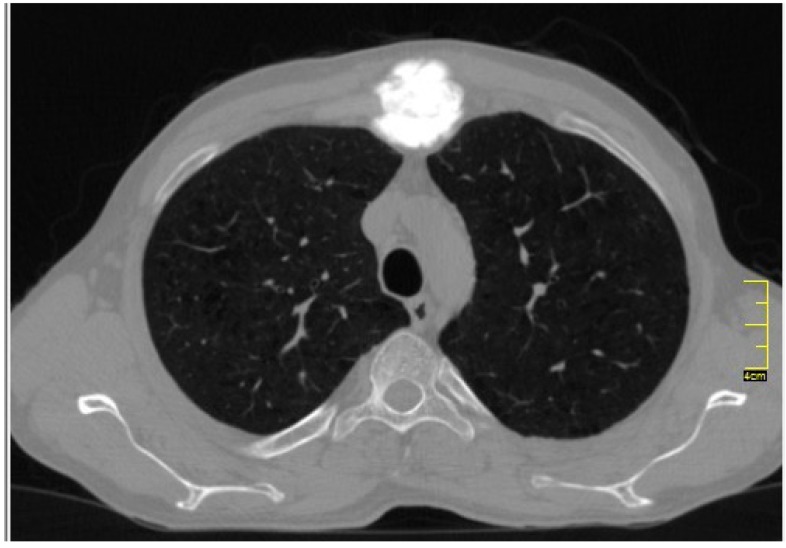

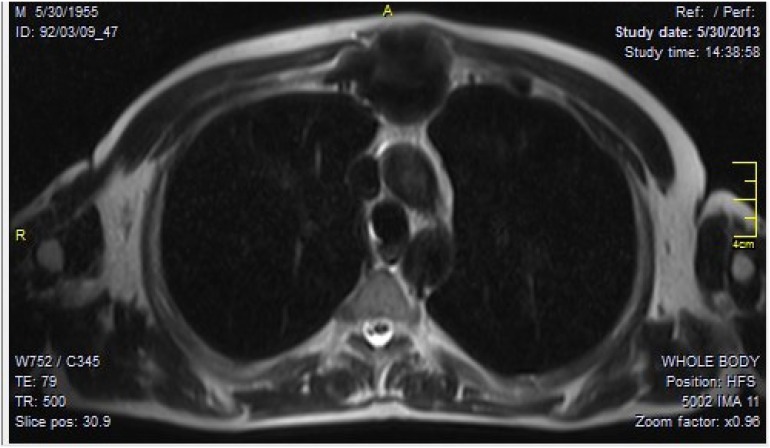

Axial CT images showed a large densely ossified mass located on the manubriosternal angle, which was extending posteriorly into the mediastinum as well as displacing the overlying anterior soft tissues [Figure 2]. MRI of the sternum showed a large retrosternal expansile destructive mass with new bone formation [Figure 3]. It was extending into the anterior mediastinum, however the main mediastinal vessels were not involved. Pre-operative pulmonary function test and cardiac evaluation were normal. Using high resolution pulmonary CT scan and bone scan, we ruled out pulmonary and distant metastases.

Figure 2.

Axial computed Tomography (CT) image showed a large densely calcified mass, situated on the manubriosternal angle.

Figure 3.

T1-weighted MRI of chest. Axial view demonstrated a large retrosternal expansile destructive mass with central signal loss due to tumor necrosis. The lesion extends to anterior mediastinum as well as overlying anterior soft tissues.

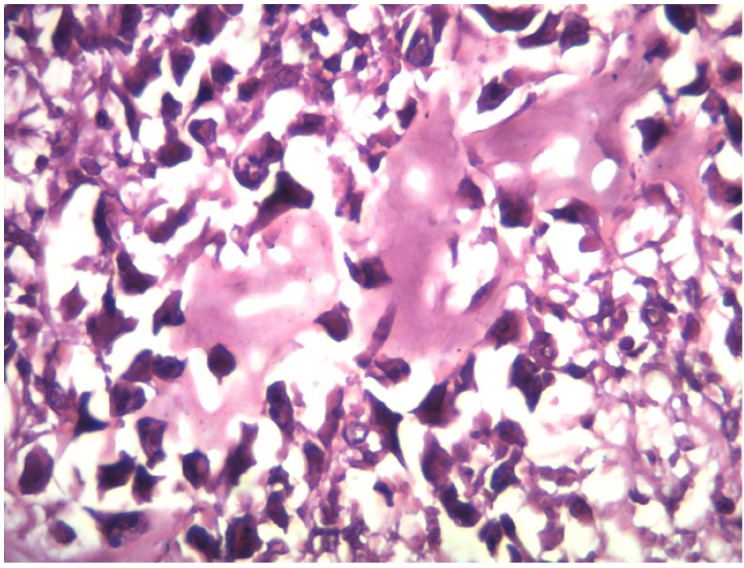

After a thorough tumor work-up, the patient underwent CT guided needle biopsy, but it was inconclusive. We then performed an incisional biopsy, which was suggestive of a high grade osteosarcoma [Figure 4].

Figure 4.

Microscopic appearance of the surgical specimen confirmed the diagnosis of high grade steosarcoma.

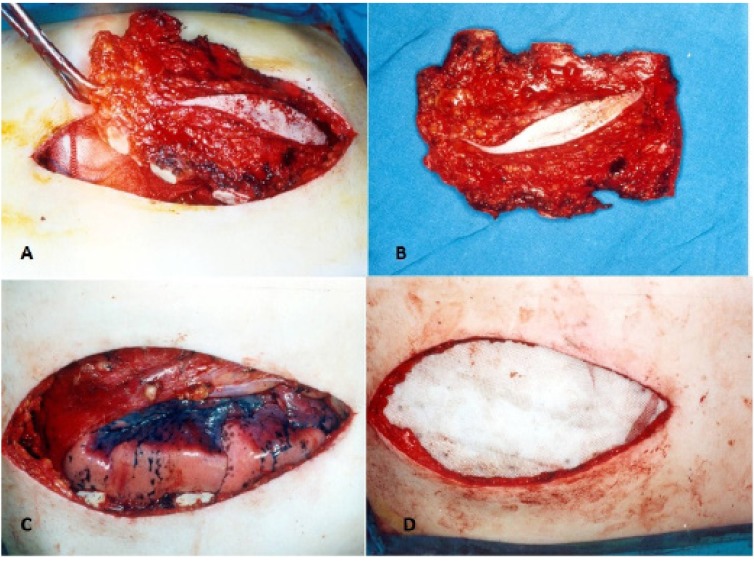

After a course of neo-adjuvant chemotherapy, the patient underwent tumor resection. A midline skin incision over the sternum was made covering the previous scar of the incisional biopsy. We resected the tumor with a safe margin including the manubrium sterni, the upper and lower limits of tumor with 2 cm margins beyond the tumor mass, and the bilateral costal cartilage of the sternal body [Figure 5A-B]. The sternal defect was reconstructed using synthetic mesh and bone cement (sandwiched mesh) and fixed to the ribs and peristernal structures by nylon sutures [Figure 5C-D]. We covered the region of sternal defect using pectoralis major muscles flap and skin.

Figure 5.

Surgical resection of sternal tumor and reconstruction with mesh.

Post-operative chest x-ray showed intact mesh with correct integration [Figure 6]. The margins of the resected tumor were free of tumor cells showing the achievement of clear margins after wide resection of the tumor. Also no evidence of lymph node involvement were detected. He received six cycles of adjuvant chemotherapy comprising of Adryamycin (35mg /m2) days 1-3 and Cisplatin (150 mg/m2) on day 1. Also external beam radiotherapy was added with 66 GY at 2GY per fraction.

Figure 6.

Post operation CXR showed the mesh graft was intact with correct integration.

After one-year follow-up, the patient has a normal life and performs the usual daily activities with no difficulty. Focal recurrence or metastatic disease was not developed during this period.

Discussion

Involvement of the sternum by neoplastic process is very rare with most cases being metastatic lesions from the lung, thyroid, kidney, and breast cancers (3). Studies have shown less than 1% of primary bone tumors occur in the sternum with chondrosarcoma being the most common primary malignant tumor while osteosarcoma is a malignant mesenchymal tumor that arises from within the chest wall (9). This tumor commonly involves the ribs, scapula, and clavicles (10). On the other hand, this tumor may rise in patients with previous radiation therapy. This type of osteosarcoma develops after a period from exposure, varying from 5 years to as delayed as 50 years. Yoshihisa Kadota et al reported a radiation-induced osteosarcoma in a 49-year-old patient 17 years after mediastinal irradiation for a stageIII thymoma (11). Post-radiation osteosarcomas usually involve the pelvis, sternum, and spine (12).

The chest wall osteosarcoma occurs in 2 age groups including younger adults presenting with the osseous type, and patients over 50 years with extra osseous type (10). Although this tumor can cause painful swelling in upper chest wall, especially if growing laterally toward the ribs, it can present with no symptoms (12). Our patient presented with a mass in the middle part of his sternum since 3 month ago. Chawla RK et al reported a similar case with sternal mass ending to the diagnosis of osteosarcoma (9).

In radiographs, the tumor appears as a mass lesion containing osteolytic bone destruction with some ossified areas. CT scan usually shows sclerotic, lytic, or mixed pattern of an expansile lesion with irregular borders. It seems to be the best imaging modality in showing bone destruction and calcification pattern of the tumors. For the assessment of soft tissue extension and extra osseous, intramedullary, and bone marrow involvement, MRI is superior to other imaging modalities (13). Ultrasonic guided True-cut needle biopsy may be used for the diagnosis, however open biopsy is recommended to obtain sufficient specimen for full histological study (1, 2).

Although some studies have suggested a number of risk factors including genetic predisposition, bone dysplasia, and radiation, we could not find a specific risk factor in our patient (13). There is a limited experience with these tumors. Wide tumor resection is essential for successful treatment (14). Moreover, other adjuncts including radiotherapy and multi agent chemotherapy should be considered.

References

- 1.Wittig JC, Bickels J, Priebat D, Jelinek J, Kellar-Graney K, Shmookler B, et al. Osteosarcoma: a multidisciplinary approach to diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2002; 65(6):1123–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Picci P. Osteosarcoma (osteogenic sarcoma) Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:6. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-2-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Downey RJ, Huvos AG, Martini N. Primary and secondary malignancies of the sternum. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1999;11(3):293–6. doi: 10.1016/s1043-0679(99)70071-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burt M. Primary malignant tumors of the chest wall. The Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center experience. Chest Surg Clin N Am. 1994; 4(1):137–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Douglas YL, Meuzelaar KJ, van der Lei B, Pras B , Hoekstra HJ. Osteosarcoma of the sternum. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1997; 23(1):90–1. doi: 10.1016/s0748-7983(97)80153-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.KK U. Dahlin's bone tumors: general aspects and data on 11,087 cases. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Restrepo CS, Martinez S, Lemos DF, Washington L , McAdams HP, Vargas D, et al. Imaging appearances of the sternum and sternoclavicular joints. Radiographics. 2009; 29(3):839–59. doi: 10.1148/rg.293055136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aslam M, Rajesh A, Entwisle J, Jeyapalan K. Pictorial review: MRI of the sternum and sternoclavicular joints. Br J Radiol. 2002; 75(895):627–34. doi: 10.1259/bjr.75.895.750627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chawla RK, Madan A, Madoiya R, Chawla A. Potato swelling of sternum. Lung India. 2013; 30(3):219–21. doi: 10.4103/0970-2113.116234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.O'Sullivan P, O'Dwyer H, Flint J, Munk PL, Muller NL. Malignant chest wall neoplasms of bone and cartilage: a pictorial review of CT and MR findings. Br J Radiol. 2007; 80(956):678–84. doi: 10.1259/bjr/82228585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kadota Y, Utsumi T, Inoue M, Sawabata N, Minami M, Okumura M. Radiation-induced osteosarcoma 17 years after mediastinal irradiation following surgical removal of thymoma. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2010; 58(12):651–3. doi: 10.1007/s11748-010-0587-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Unni KK. Osteosarcoma of bone. J Orthop Sci. 1998;3:287–94. doi: 10.1007/s007760050055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sönmez G, Ö ztürk E, Mutlu H, Görür AR, Kutlu A, Mahiroğulları M, et al. Computerized Tomography Findings of a Sternal Osteosarcoma. European Journal of General Medicine. 2009; 6(1):46–8. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ren P, Zhang J, Zhang X. Resection of primary sternal osteosarcoma and reconstruction with homologous iliac bone: case report. J Formos Med Assoc. 2010;109(4):309–14. doi: 10.1016/S0929-6646(10)60057-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]