Abstract

Objective(s):

To examine the expressions of CD11a, CD11b, and CD11c integrins in the myocardial tissues of rats with isoproterenol-induced myocardial hypertrophy. This study also provided morphological data to investigate the signal transduction mechanisms of myocardial hypertrophy and reverse it.

Materials and Methods:

A myocardial hypertrophy model was established by subcutaneously injecting isoprenaline in healthy adult Sprague-Dawley rats. Myocardial tissues were obtained, embedded in conventional paraffin, sectioned, and stained with hematoxylin. Pathological changes in myocardial tissues were then observed. The expressions and distributions of CD11a, CD11b, and CD11c integrins were detected by immunohistochemistry. Changes in the mRNA expressions of CD11a, CD11b, and CD11c in the myocardial tissues of rats were detected by RT-PCR. Image analysis software was used to determine the expressions of CD11a, CD11b, and CD11c integrins quantitatively.

Results:

Immunohistochemical results showed that the positive expressions of CD11a, CD11b, and CD11c integrins increased significantly in the experimental group compared with those in the control group. The mRNA expressions of CD11a, CD11b, and CD11c in the myocardial tissues of rats were consistent with the immunohistochemical results.

Conclusion:

The increase in the protein expressions of CD11a, CD11b, and CD11c integrins may have an important role in the occurrence and development of myocardial hypertrophy.

Keywords: CD11a, CD11b, CD11c, Integrin, Myocardial hypertrophy, Rat

Introduction

Increasing incidence and prevalence of heart failure (HF) is one of the main causes of morbidity and mortality in elderly (1, 2). The pathogenesis of HF is complex and often associated with cardiac remodeling, which involves cardiac myocyte hypertrophy, fetal program re-expression, and phenotypic changes in the extracellular matrix (ECM) (3-5). Myocardial hypertrophy possibly occurs as an adaptive response to pressure or volume overload by decreasing wall stress; chronic left ventricle hypertrophy is strongly associated with chronic HF and death. Chronic left ventricle hypertrophy is also considered as a maladaptive process, thereby inducing a "fetal" gene program and pro-hypertrophic signaling pathways (6-10). In an adult heart, hypertrophic growth is caused by signals stimulated at a cell surface; these signals are then transmitted via receptors or channels that activate intracellular signaling cascades and affect nuclear cues, thereby alter gene expression (11-14). Molecular machineries that direct mechanical sensing in cardiac myocytes are partially understood. In some cases, cell surface adhesion receptors called integrins are important detectors of mechanical load (15, 16).

Integrins are involved in various physiological and pathological processes In vivo, such as organogenesis, gene expression regulation, cell proliferation and differentiation, and tumor cell adhesion and migration. Each member of the integrin family is composed of a heterodimer molecule formed by non-covalently bonded α and β chains (subunit). β2 subfamily is formed by non-covalently connecting a β2 subunit with an α subunit of CDlla, CDllb, and CDllc (17, 18). Previous reports showed that human ventricular myocyte proliferation is associated with β2 integrin adhesion, and β2 expression can lead to In vitro ventricular myocyte hypertrophy of cultured cells (19, 20). Integrin αv, in complex with β1, β3, β5, β6 or β8 integrin subunit, also forms receptors for fibronectin or vitronectin. Mice are lacking the αv subunit, therefore devoid of all αv integrin containing heterodimers, make severe developmental defects in vasculogenesis and organogenesis (21, 22). However, studies on integrin and heart development are few. Furthermore, studies on β2 subfamily of integrins in heart development have not yet been conducted. Such adhesive molecular ligand specificity is possibly determined by α subunits. In the present study, we examined the expression of CD11a, CD11b, and CD11c in the myocardial tissues of the rat using a Isoprenaline (ISO)-induced myocardial hypertrophy model. We also investigated the signal transduction mechanisms of myocardial hypertrophy and actions to reverse it.

Materials and Methods

Establishment of a rat model of myocardial hypertrophy

The rat model of myocardial hypertrophy was established according to previous studies (12). Twenty healthy adult Sprague-Dawley rats (10 males and 10 females; weight=200±20 g) were provided by the Experimental Animal Center of Xinxiang Medical University and this study was conducted with approval from the Ethics Committee of Xinxiang Medical University. We randomly selected 5 males and 5 females rats and mixed them as one group. The rats in the experimental group were subcutaneously injected with 8 mg/kg/day of ISO (Shanghai Harvest Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., China) twice a day for five consecutive days. The rats in this group were then observed for 48 hr. (2) The rats in the control group were subcutaneously injected with 2 ml/kg/day of physiological saline according to the same procedure used for the experimental group.

Determination of myocardial hypertrophy index

The body weights (BW) of the rats in the two groups were immediately measured at the end of the observation period. To narcotize the rats, we intraperitoneally injected them with 20% ethyl carbamate solution (750 mg/kg). Supination and fixation were then performed. Regular shearing and disinfection were also conducted. Their chests were opened to remove the heart. Afterward, the heart was washed with pre-cooled normal saline until the flushing fluid was no longer red, and a clean filter paper was used to absorb moisture. The tissues and the blood vessels surrounding the heart were cut, and heart weight (HW) was measured. The left and the right atrium along the coronary artery groove were removed. The right ventricular free wall along the interventricular groove was also removed, and the left ventricular weight (LVW) was measured. HW/BW and LVW/BW were calculated to determine the degree of myocardial hypertrophy. Two myocardia (each myocardium weighed approximately 0.3 g) of the left ventricle were obtained from the two groups of rats. One myocardium was immediately placed in 4% neutral formaldehyde stationary liquid, embedded with conventional paraffin, sectioned, and subjected to immunohistochemistry. The other myocardium was immediately placed in liquid nitrogen.

Immunohistochemical method

The myocardial tissue was embedded in conventional paraffin and then sectioned using an SP-9001 immunohistochemical kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. Primary antibodies of CD11a, CD11b, and CD11c (1:100, Wuhan Boster Company) were incubated overnight at 4°C and then incubated at 37°C for 30 min in IgG/Biotin IgG and SABC liquid. The specimens were stained with DAB and then re-dyed with hematoxylin. PBS was used instead of DAB and hematoxylin for the negative control specimens. Afterward, these specimens were observed under a light microscope and photographed. Brown reaction granules found in the cells indicated positive results.

Six myocardial specimens were obtained from each group of immunohistochemical results. Five sections were selected from each specimen, and four views were obtained from the selected sections that showed uniform myocardial tissue distribution and dyeing. The results were quantitatively analyzed using Motic BA400 pathological graphic analysis system at magnification of 400×. The key indicators considered in this study were the positive expression area and the average optical density.

Real time- PCR (RT-PCR)

The heart tissue was removed from liquid nitrogen, and total RNA was extracted using an AxyPrep total RNA preparation kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. UV absorbances at 260 and 280 nm were determined using a UVmini-1240 UV spectrophotometer. RNA integrity was detected by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis. CD11a, CD11b, and CD11c primer sequences (Table 1) were designed using Primer 5 primer design software.

Table 1.

Oligonucleotide primers of CD11, CD11b, CD11c, and β-actin

| Gene | Sense | Antisense | Product (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD11a | aggagactgagagcgagctg | tcaaagcaggcaaacagatg | 573 |

| CD11b | gagaactggttctggcttgc | tcagttcgagccttctt | 464 |

| CD11c | ggtgcaaagaccaccttcat | gacgtttgaagaagccaagc | 783 |

| β-actin | cacccgcgagtacaaccttc | cccatacccaccatcacacc | 206 |

These primers were synthesized by the Shanghai Biological Engineering Technology Co, Ltd, purified using the PAGE method, dissolved in non-RNase water to obtain a final concentration of 100 µmol/l, and preserved at -70°C for later use. First-strand cDNA was synthesized using an M-MLV reverse transcription kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. CD11a, CD11b, and CD11c were amplified by PCR, and amplification reactions were recorded in one system by using β-actin as an internal reference. The reaction conditions which used were as follows: initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min; loop degeneration at 94°C for 30 sec; renaturation at 55°C for 30 sec; and extension at 72°C for 10 min. The PCR products were electrophoresed in 1.5% agarose gel (containing ethidium bromide with a final concentration of 0.5 mg/ml). GeneGenius Syngene Agar imaging analysis system and Gelworks10 software were used to scan and record the results. A semi-quantitative analysis by ratio was conducted between the target segment and the gray value of β-actin.

Statistical analyses

Results are reported as the mean ± SD. Statistical comparisons were performed using Student's t-test. Significance was set at P<0.05.

Results

Determination of myocardial hypertrophy index

The experimental group showed an evident increase in HW/BW and LVW/BW based on the results of the myocardial hypertrophy index tests compared with the control group (Table 2).

Table 2.

Index of rat cardiac hypertrophy model ( ± s)

| n | HW/BW (mg/g) | LVW/BW (mg/g) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental group | 10 | 6.150 ± 0.619* | 4.309 ± 0.482** |

| Control group | 10 | 4.388 ± 0.308 | 2.081 ± 0.196 |

HW: heart weight; BW: body weights; LVW: ventricular weight. Data are expressed as means ± SD. Asterisk denotes a response that is significantly different from the control group

P<0.05,

P<0.01)

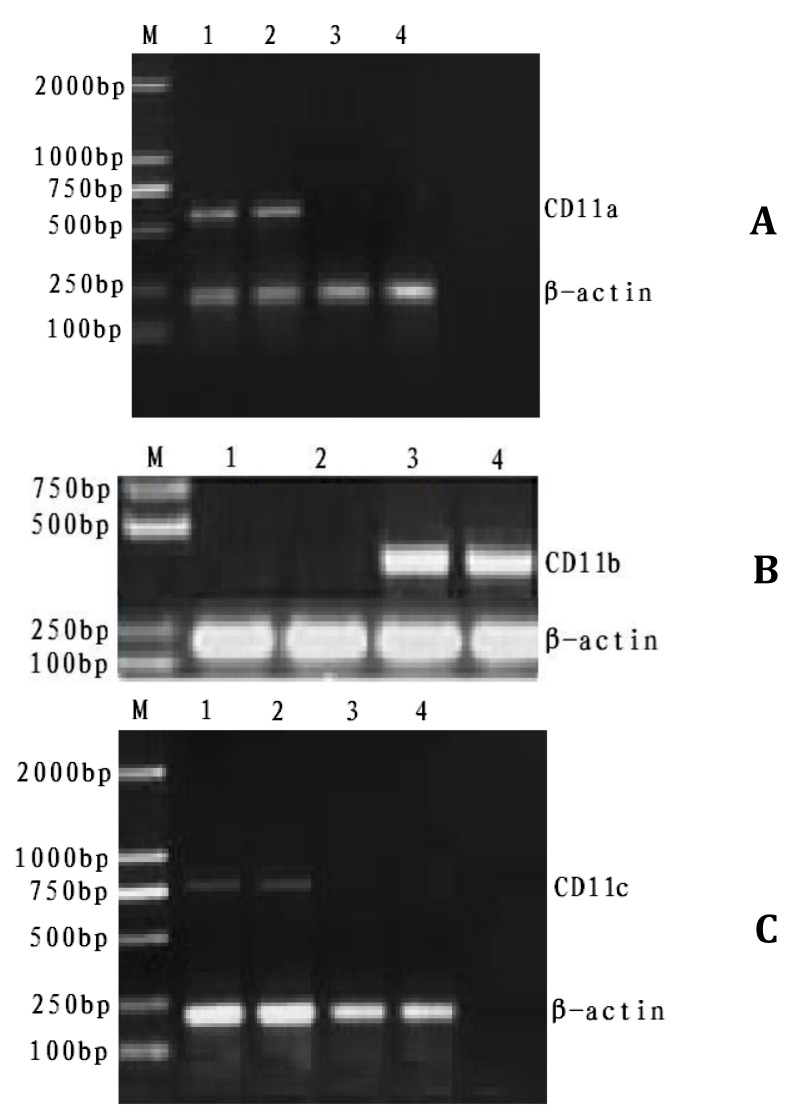

RT-PCR amplification of CD11a, CD11b, and CD11c

Figure 1 showed that unique bands were observed at 500 bp to 600 bp, 400 bp to 500 bp, and 700 bp to 800 bp in the experimental and the control group. Significant differences (P<0.01) were found in the ratios of CD11a, CD11b, and CD11c. β-actin gray value was compared in pairs using SPSS 14.0 by variance analysis (Table 3).

Figure 1.

RT-PCR products of CD11a, CD11b, and CD11c

A: RT-PCR products of CD11a M: Marker 1-2: experimental group; 3-4: control group

B: RT-PCR products of CD11b M: Marker 1-2: control group; 3-4: experimental group

C: RT-PCR products of CD11c M: Marker 1-2: experimental group; 3-4: control group

Table 3.

Comparison of the average area and brightness of CD11a, CD11b, and CD11c expressions in the myocardium ( ±s)

| n | Average brightness | Average area | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD11a | CD11b | CD11c | CD11a | CD11b | CD11c | ||

| Experimental group | 120 | 0.36 ± 0.02** | 0.41 ± 0.02** | 0.22 ± 0.01** | 182 ± 9** | 198 ± 8** | 127 ± 5** |

| Control group | 120 | 0.11 ± 0.02 | 0.16 ± 0.02 | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 22 ± 5 | 20 ± 3 | 18 ± 4 |

Data are expressed as means ± SD. Asterisk denotes a response that is significantly different from the control group

P<0.01

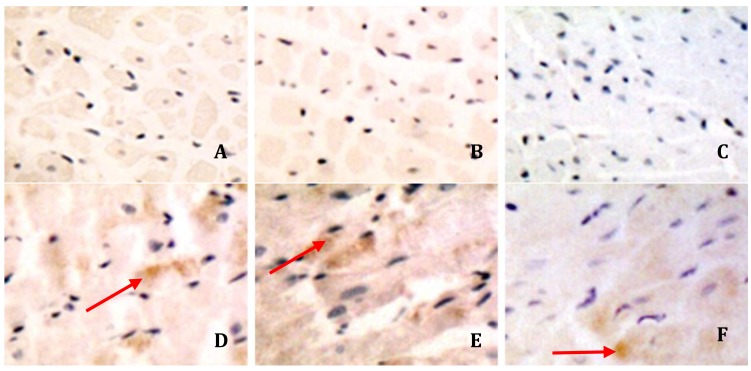

Immunohistochemical results

In the experimental group, CD11a, CD11b, and CD11c were highly expressed in a few myocardial cells, whereas in the control group CD11c were only weakly expressed. The expression of CD11a, CD11b, and CD11c was mainly distributed in the myocardial cell cytoplasm and in an area next to the capsule (Figure 2), CD11a, CD11b, and.

Figure 2.

Expressions of CD11a, CD11b, and CD11c in the myocardial tissue at mRNA levels

A: CD11a of control group

B: CD11b of control group

C: CD11c of control group

D: CD11a of experimental group

E: CD11b of experimental group

F: CD11c of experimental group

Arrows was used to indicate the positive expression of integrins in experimental group.

Discussion

Myocardial hypertrophy is a normal adjustment in response to wall stress when cardiac load is increased (23-27). The pathogenesis of myocardial hypertrophy has been a controversial topic in the study of cardiovascular diseases (28, 29); however, no clear conclusions have been presented. In this study, an ISO-induced myocardial hypertrophy model was established. Immunohistochemistry and RT-PCR were performed to investigate the changes in protein expressions, distribution, and mRNA expressions of CD11a, CD11b, and CD11c integrins.

The immunohistochemical results showed that the protein expressions of CD11a, CD11b, and CD11c integrins in the experimental group were higher than those in the control group with expressed areas mainly in the cytoplasm. ECM cells interact with one another to maintain the stability of organisms and ensure that pathophysiological signals are regulated (30). As a major receptor of ECM, integrins should be correctly expressed and functionally developed to maintain the normal functioning of the cardiovascular system in adults (31, 32). In some cardiovascular diseases, such as cardiomegaly, dilated cardiomyopathy, and myocardial infarction, EMC components (e.g., cardiac output) have changed (33). Disease models have not yet shown the expressions of special integrins; therefore, further studies should be conducted to confirm whether or not the changes in the location of integrins are similar to the changes in EMC components. Some studies demonstrated that mindin serves as a novel mediator that protects against cardiac hypertrophy and the transition to heart failure by blocking AKT/GSK3β and TGF-β1-Smad signaling (5). A β3 integrin / ubiquitination / NF-κB pathway contributes to compensatory hypertrophic growth (34). Other studies indicated that the loss of specific integrin function could be a key mechanism for calpain-mediated programmed cell death of cardiomyocytes in pressure-overload myocardium (35). In fact, cardiomegaly can be caused by many factors, including integrins. In cardiomegaly, ventricular dilatation, and HF models, morphological changes were observed in myocardial cells. Thus, integrin expressions in cells should be changed to adjust to such morphological changes (36). However, the function of PTEN in myocardial hypertrophy remains complex.

The results of this study showed that CD11a, CD11b and CD11c expression increased in the state of cardiac hypertrophy. This may be that after β2 integrin combined with the corresponding ligand outside the cell membrane, signals of hypertrophy of cell growth would be transmitted into the cell through a number of different cell signal transduction pathways. So hypertrophy gene expression would be activated and the corresponding proteins synthesis involved in the occurrence and development of cardiac hypertrophy.

Conclusion

The results of this study revealed that the expressions of CD11a, CD11b, and CD11c increased in myocardial hypertrophy, indicating that these three integrins are involved in the occurrence and development of myocardial hypertrophy.

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by the Science and Technology Foundation of Henan Province, China (122102310195, 12A180022, 09S081). The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Dickstein K, Cohen-Solal A, Filippatos G, McMurray JJ, Ponikowski P, Poole-Wilson PA, et al. ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2008: the task force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2008 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association of the ESC (HFA) and endorsed by the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM) Eur Heart J. 2008;10:933–989. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2008.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bettink SI, Werner C, Chen CH, Muller P, Schirmer SH, Walenta KL, et al. Integrin-linked kinase is a central mediator in angiotensin II type 1- and chemokine receptor CXCR4 signaling in myocardial hypertrophy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun . 2010;397:208–213. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.05.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Swynghedauw B, Delcayre C, Samuel JL, Mebazaa A, Cohen-Solal A. Molecular mechanisms in evolutionary cardiology failure. Ann N Y Acad Sci . 2010;1188: 58–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ashrafian H, Frenneaux MP, Opie LH. Metabolic mechanisms in heart failure. Circulation. 2007;116:434–448. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.702795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yan L, Wei X, Tang QZ, Feng J, Zhang Y, Liu C, et al. Cardiac-specific mindin overexpression attenuates cardiac hypertrophy via blocking AKT/GSK3beta and TGF-beta1-Smad signalling. Cardiovasc Res . 2011;92:85–94. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Frey N, Katus HA, Olson EN, Hill JA. Hypertrophy of the heart: a new therapeutic target? Circulation . 2004;109:1580–1589. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000120390.68287.BB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Levy D, Garrison RJ, Savage DD, Kannel WB, Castelli WP. Prognostic implications of echocardiographically determined left ventricular mass in the Framingham Heart Study. N Engl J Med . 1990;322:1561–1566. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199005313222203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Satoh M, Ogita H, Takeshita K, Mukai Y, Kwiatkowski DJ, Liao JK. Requirement of Rac1 in the development of cardiac hypertrophy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:7432–7437. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510444103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Murtaza I, Wang HX, Mushtaq S, Javed Q, Li PF. Interplay of phosphorylated apoptosis repressor with CARD, casein kinase-2 and reactive oxygen species in regulating endothelin-1-Induced cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2013;16:928–935. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Najafi M. Effects of postconditioning, preconditioning and perfusion of L-carnitine during whole period of ischemia/ Reperfusion on cardiac hemodynamic functions and myocardial infarction size in isolated rat heart. Iran J Basic Med Sci . 2013;16:640–647. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olson EN, Schneider MD. Sizing up the heart: development redux in disease. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1937–1956. doi: 10.1101/gad.1110103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Molkentin JD, Dorn Ⅱ GW. Cytoplasmic signaling pathways that regulate cardiac hypertrophy. Annu Rev Physiol . 2001;63:391–426. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.63.1.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inanloo Rahatloo K, Davaran S, Elahi E. Lack of Association between the MEF2A Gene and Coronary Artery Disease in Iranian Families. Iran J Basic Med Sci . 2013;16:950–954. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mehdizadeh R, Parizadeh MR, Khooei AR, Mehri S, Hosseinzadeh H. Cardioprotective effect of saffron extract and safranal in isoproterenol-induced myocardial infarction in wistar rats. Iran J Basic Med Sci . 2013;16:56–63. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li R, Wu Y, Manso AM, Gu Y, Liao P, Israeli S, et al. beta1 integrin gene excision in the adult murine cardiac myocyte causes defective mechanical and signaling responses. Am J Pathol. 2012;180:952–962. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rastegar T, Minaee MB, Habibi Roudkenar M, Raghardi Kashani I, Amidi F, Abolhasani F, et al. Improvement of expression of alpha6 and beta1 Integrins by the co-culture of adult mouse spermatogonial stem cells with SIM mouse embryonic fibroblast cells (STO) and growth factors. Iran J Basic Med Sci. 2013;16:134–139. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Langeggen H, Berge KE, Johnson E, Hetland G. Human umbilical vein endothelial cells express complement receptor 1 (CD35) and complement receptor 4 (CD11c/CD18) in vitro. Inflammation . 2002;26:103–110. doi: 10.1023/a:1015585530204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vorup-Jensen T, Ostermeier C, Shimaoka M, Hommel U, Springer TA. Structure and allosteric regulation of the alpha X beta 2 integrin I domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A . 2003;100:1873–1878. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0237387100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pham CG, Harpf AE, Keller RS, Vu HT, Shai SY, Loftus JC, et al. Striated muscle-specific beta(1D)-integrin and FAK are involved in cardiac myocyte hypertrophic response pathway. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;279:H2916–H2926. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.6.H2916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ross RS, Pham C, Shai SY, Goldhaber JI, Fenczik C, Glembotski CC, et al. Beta1 integrins participate in the hypertrophic response of rat ventricular myocytes. Circ Res. 1998;82:1160–1172. doi: 10.1161/01.res.82.11.1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Larjava H, Koivisto L, Heino J, Hakkinen L. Integrins in Periodontal Disease. Exp Cell Res . 2014;325:104–110. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2014.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hynes RO. Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell. 2002;110:673–687. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00971-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Simone G, Devereux RB, Celentano A, Roman MJ. Left ventricular chamber and wall mechanics in the presence of concentric geometry. J Hypertens . 1999;17:1001–1006. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199917070-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.de Simone G, Greco R, Mureddu G, Romano C, Guida R, Celentano A, et al. Relation of left ventricular diastolic properties to systolic function in arterial hypertension. Circulation . 2000;101:152–157. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.2.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grossman W, Paulus WJ. Myocardial stress and hypertrophy: a complex interface between biophysics and cardiac remodeling. J Clin Investig . 2013;123:3701–3703. doi: 10.1172/JCI69830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kucukler N, Kurt IH, Topaloglu C, Gurbuz S, Yalcin F. The effect of valsartan on left ventricular myocardial functions in hypertensive patients with left ventricular hypertrophy. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) . 2012;13:181–186. doi: 10.2459/JCM.0b013e3283511f00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hua Y, Zhang Y, Ren J. IGF-1 deficiency resists cardiac hypertrophy and myocardial contractile dysfunction: role of microRNA-1 and microRNA-133a. J Cell Mol Med . 2012;16:83–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01307.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li YC, Liu YY, Hu BH, Chang X, Fan JY, Sun K, et al. Attenuating effect of post-treatment with QiShen YiQi Pills on myocardial fibrosis in rat cardiac hypertrophy. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc . 2012;51:177–191. doi: 10.3233/CH-2011-1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schuster A, Ishida M, Morton G, Bigalke B, Moonim MT, Nagel E. Value of cardiovascular magnetic resonance imaging in myocardial hypertrophy. Clin Res cardiol . 2012;101:237–238. doi: 10.1007/s00392-011-0401-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cines DB, Pollak ES, Buck CA, Loscalzo J, Zimmerman GA, McEver RP, et al. Endothelial cells in physiology and in the pathophysiology of vascular disorders. Blood. 1998;91:3527–3561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bouvard D, Brakebusch C, Gustafsson E, Aszodi A, Bengtsson T, Berna A, et al. Functional consequences of integrin gene mutations in mice. Circ Res . 2001;89:211–223. doi: 10.1161/hh1501.094874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Caiado F, Dias S. Endothelial progenitor cells and integrins: adhesive needs. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair. 2012;5:4. doi: 10.1186/1755-1536-5-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leslie K, Blay R, Haisch C, Lodge A, Weller A, Huber S. Clinical and experimental aspects of viral myocarditis. Clin Microbiol Rev . 1989;2:191–203. doi: 10.1128/cmr.2.2.191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Johnston RK, Balasubramanian S, Kasiganesan H, Baicu CF, Zile MR, Kuppuswamy D. Beta3 integrin-mediated ubiquitination activates survival signaling during myocardial hypertrophy. FASEB J . 2009;23:2759–2771. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-127480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suryakumar G, Kasiganesan H, Balasubramanian S, Kuppuswamy D. Lack of beta3 integrin signaling contributes to calpain-mediated myocardial cell loss in pressure-overloaded myocardium. J Cardiovas Pharmacol . 2010;55:567–573. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e3181d9f5d4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blauwet LA, Cooper LT. Myocarditis. Prog Cardiovasc Dis . 2010;52:274–288. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2009.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]