Abstract

Large numbers of microorganisms colonise the skin and mucous membranes of animals, with their highest density in the lower gastrointestinal tract. The impact of these microbes on the host can be demonstrated by comparing animals (usually mice) housed under germ-free conditions, or colonised with different compositions of microbes. Inbreeding and embryo manipulation programs have generated a wide variety of mouse strains with a fixed germ-line (isogenic) and hygiene comparisons robustly show remarkably strong interactions between the microbiota and the host, which can be summarised in three axioms. (I) Live microbes are largely confined to their spaces at body surfaces, provided the animal is not suffering from an infection. (II) There is promiscuous molecular exchange throughout the host and its microbiota in both directions 1. (III) Every host organ system is profoundly shaped by the presence of body surface microbes. It follows that one must draw a line between live microbial and host “spaces” (I) to understand the crosstalk (II and III) at this interesting interface of the host-microbial superorganism. Of course, since microbes can adapt to very different niches, there has to be more than one line. In this issue of EMBO Reports, Johansson and colleagues have studied mucus, which is the main physical frontier for most microbes in the intestinal tract: they report how different non-pathogenic microbiota compositions affect its permeability and the functional protection of the epithelial surface 2.

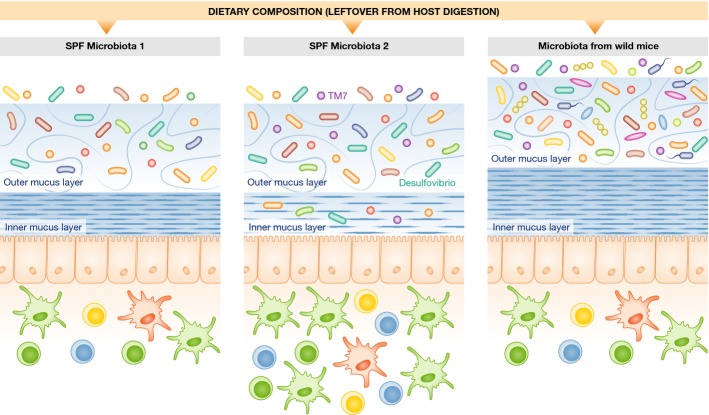

Peaceful host-microbial mutualism provides a healthy lifestyle for both the host and its commensal microbes. The host gut contributes a rich mix of microbial nutrients, whilst bacteria considerably extend the metabolic capability encoded in the host genome, to catabolise otherwise indigestible foodstuffs, provide essential amino acids, synthesise vitamins, complete the bile-salt cycle and enable pre-systemic metabolism of drugs and toxins. In addition, the intense competition from endogenous commensals limits colonisation and invasion by pathogens. The intestinal epithelium should be kept relatively sterile to avoid inflammation or induction of surplus immunological responses. Mucus—which contains antibacterial peptides and antibodies—plays a key role in maintaining the necessary spatial host-microbial segregation 3. It is a gel formed by highly glycosylated mucin proteins secreted from intestinal epithelial goblet cells. In the colon, where most microbes exist, mucus can be clearly subdivided into a tight inner layer composed of tightly stacked mucin polymers and a looser outer layer, as the structure is broken down by proteolysis. The outer mucus layer is colonised with microbes, whereas the inner layer is relatively sterile and impenetrable—colloquially dubbed the “demilitarisation zone” (Fig1; 3, 4).

Figure 1. Variations in commensal microbiota affect mucus structure and possibly susceptibility to intestinal pathologies.

Hygiene conditions and the choice of food in animal housing can influence the composition of the murine colon microbiota. Jakobsson et al 2 observed two different stable SPF microbiota consortia in their animal holding, which differently affect mucus structure. Microbiota containing members of the Proteobacteria and TM7 phyla, such as Desulfovibrio and TM7 bacteria (middle), induce an altered mucus structure, more penetrable by bacteria, and associated with increased immune cell infiltration into the lamina propria. Wild-living mice have an even thicker mucus layer and a tighter inner mucus structure that is free of bacteria (right).

The presence of a microbiota has been implicated in mucus maturation, since germ-free mice have thinner and less firm mucus 4. In addition, several commensal bacteria can use the glycans from glycosylated mucin proteins as a carbon source, thereby breaking down mucus 5, 6. From the host side, mucin-deficient mice show that a stable mucus layer is crucial to prevent host intestinal pathology 7. Germ-free/colonised and strain-combination observations inform us of extreme situations, whereas inter-individual microbiota variation is more subtle, so it is important to understand how variable compositions of a normal non-pathogenic microbiota can affect the structure and function of mucus layers.

Jakobsson et al 2 now describe two separate specific pathogen-free (SPF) C57BL/6 mouse colonies in their vivarium, which have differences in microbiota composition associated with changes in mucus structure and function. Although the overall thickness of the mucus layers is the same between the two colonies, differences in the penetration of fluorescent beads of bacterial size imply that the structure and permeability of the colonic inner mucus layer is altered by differences in colonisation.

Diet can shape both the composition and behaviour of mammalian gut microbial communities and epithelial function 8. At the outset, the two mice colonies had been fed with different chow formulations, so Jakobsson et al performed food exchange experiments. These showed that altered dietary manipulation will also alter both the microbiota composition and the mucus structure. However, the effects of a dietary swap are far smaller than the differences observed between the two mouse colonies, implying that microbial composition per se plays a key role. These conclusions were supported by transplanting caecal contents from each of the two SPF colonies into germ-free mice. The differences observed in the original SPF colonies could be recapitulated in the germ-free recipients, indicating that the functional alterations observed in the inner mucus structure are a consequence of the shift in microbiota composition.

Experimental animals are generally used in an endeavour to model natural biology. Jakobsson et al also analysed the mucus structure of wild free-living mice and observed an even thicker bacteria-free inner mucus layer. This trend is very reassuring, although the wild mice are not necessarily pathogen-free, and inflammasome activity is known to provoke mucin secretion 9. Taking a more general perspective, this study analyses “top-down” models of different complex microbiotas. This has the undoubted merit of revealing the functional importance of variations in complex microbiota compositions (which is the natural situation we seek to understand). On the other hand, experimental variability between different colonies in the same vivarium may be kaleidoscoped as one moves between the vivaria of different institutions. This problem could be solved through a complementary “bottom-up” approach that relates mucus composition and function (and other host-microbial phenotypes) to stable, defined, medium-diversity microbiotas. In this latter setting, the requirements of microbial consortial composition and molecular signalling could ultimately be addressed. It remains a long-term goal in the field to merge the “top-down” and “bottom-up” approaches and have a sufficient variety of “isobiotic” strains of mice available for “conbiotic” factorial designs: these biological models also need to be reproducible in different institutional vivaria.

A “top-down” approach is amenable to an analysis of differences in microbial composition and encoded molecular functions. Commensal bacteria have been shown to use mucin glycans to sustain their growth, and this can be inferred from in silico analysis of bacterial genomes 5, 6. However, known mucolytic bacteria were not present in the SPF colony harbouring the looser inner mucus layer. Jakobsson et al considered other potential candidates that can influence mucus structure, including members of the genus Desulfovibrio [composed of sulphate-reducing bacteria (SRB)], and members of the Proteobacteria and TM7 Phyla. Desulfovibrio and TM7 bacteria may be considered disease-liable commensals, mainly due to their tight association with the colonic epithelium 10. However, the mice colonised with a microbiota containing these bacteria did not show signs of mucosal inflammation, possibly because of their low absolute abundance. Nevertheless, the observed epithelial cell proliferation in crypts and immune cell infiltration in the lamina propria imply an increased host–microbial crosstalk and possible susceptibility to inflammation. These observations may help to explain why some patients are more sensitive to gut infection: a more penetrable inner layer could facilitate infection by pathogens that lack an intrinsic capacity to degrade mucus.

The study by Jakobsson et al nicely shows that microbial composition and overall complexity determines mucus protective function. Certain species of bacteria in a stable non-pathogenic microbiota can dampen the protective function of the mucus, instead of promoting its maturation. The underlying molecular mechanism and the clinical association between a penetrable inner mucus layer and predisposition to intestinal diseases remain to be elucidated. Another important aspect of the study is the demonstration that the “specific pathogen-free” designation for experimental mice encompasses a wide variety of microbial and phenotypic variability, even within a fixed host genetic background. Many groups may feel that working with genetically identical mice means approximately identical starting conditions; but the impact of variations in the microbiota of experimental mice, whether between vivaria, rooms or cages, should never be underestimated.

References

- Nicholson JK, Holmes E, Kinross J, et al. Science. 2012;336:1262–1267. doi: 10.1126/science.1223813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakobsson HE, Rodriguez-Pineiro AM, Schütte A, et al. EMBO Rep. 2015;16:164–177. doi: 10.15252/embr.201439263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaishnava S, Yamamoto M, Severson KM, et al. Science. 2011;334:255–258. doi: 10.1126/science.1209791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansson ME, Phillipson M, Petersson J, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:15064–15069. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803124105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Passel MW, Kant R, Zoetendal EG, et al. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e16876. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0016876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin J, Li R, Raes J, et al. Nature. 2010;464:59–65. doi: 10.1038/nature08821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Sluis M, De Koning BA, De Bruijn AC, et al. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:117–129. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faith JJ, McNulty NP, Rey FE, et al. Science. 2011;333:101–104. doi: 10.1126/science.1206025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wlodarska M, Thaiss CA, Nowarski R, et al. Cell. 2014;156:1045–1059. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuehbacher T, Rehman A, Lepage P, et al. J Med Microbiol. 2008;57:1569–1576. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.47719-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]