Abstract

Reduction of duplicative Institutional Review Board (IRB) review for multiinstitutional studies is a desirable goal to improve IRB efficiency while enhancing human subject protections. Here we describe the Harvard Catalyst Master Reciprocal Common IRB Reliance Agreement (MRA), a system that provides a legal framework for IRB reliance, with the potential to streamline IRB review processes and reduce administrative burden and barriers to collaborative, multiinstitutional research. The MRA respects the legal autonomy of the signatory institutions while offering a pathway to eliminate duplicative IRB review when appropriate. The Harvard Catalyst MRA provides a robust and flexible model for reciprocal reliance that is both adaptable and scalable.

Keywords: institutional review boards, reliance agreement, reliance agreement models, master IRB agreements, cede review, cooperative agreement, IRB authorization agreement, multicenter clinical trials, research ethics, bioethics

Introduction and Background

Federal regulations require that institutional review board (IRB) review and approval occur before human subjects research may begin. The federal regulations date from the 1970s when most research was performed at a single institution with oversight provided by the institution's IRB. The modern medical research enterprise, however, is characterized by the proliferation of multisite clinical trials involving an ever‐increasing number of diverse sites and studies. The current system of IRB oversight of human research protections has been criticized for both wasting resources and leading to inappropriate delays in the conduct of research, particularly when multiple institutions collaborate on one clinical protocol (multisite research).1 Numerous factors may contribute to inefficiencies in IRB operations, including lack of requisite expertise for review2 and IRB interpretative variability.3, 4 Inadequate protocol documents submitted by investigators can further delay time to IRB approval.5 These problems may become particularly acute if protocols for multisite research must be approved by each site's IRB before the research may proceed. In multisite studies, review by several IRBs is burdensome;6 the burden and expense of conducting multiple and duplicative ethics reviews at several institutions has been cited as a major barrier to research, manifest in delays in research conduct in the absence of demonstrable enhanced human subjects protections.1,6.

Spurred by the NIH Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) which fosters interinstitutional research collaboration, Harvard Catalyst | The Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (Harvard Catalyst) focused on IRB processes and operations, seeking to reduce the burdens and inefficiencies described above, where appropriate and desired, to produce an integrated and comprehensive solution with the potential to improve IRB efficiency while preserving (or possibly enhancing) human subject protections.

Described herein is the resulting Harvard Catalyst Master Reciprocal Common IRB Reliance Agreement (MRA), which establishes the framework, substantive legal provisions, and operational elements essential to shift the paradigm from multiple, independent IRB reviews toward greater collaboration, consolidation and information sharing in the interests of accelerating clinical and translational (C/T) research. The MRA was developed to provide Harvard Catalyst institutions with a flexible alternative to duplicative IRB review and to support collaborative research across the participating institutions. As a framework, reciprocal reliance also offers the potential for increasing efficiency of review and decreasing investigator time spent in administrative and redundant efforts, and may help prevent (often trivial) differences among—and modifications between—protocols and informed consent forms, which can occur when multisite research is reviewed by multiple IRBs.1 While the legal document and framework of the MRA grew out of the collaborative efforts of Harvard‐affiliated institutions, it has continued to expand its reach to include additional signatories beyond Harvard and beyond the local geographic region; it has shown itself to be a flexible model suited to broad adoption.

Harvard Catalyst: meaningful opportunity for interinstitutional collaboration

Research at Harvard is a complex, shared enterprise among Harvard's 11 schools and 17 affiliated Academic Health Centers (AHCs); unlike most other medical schools, Harvard Medical School (HMS) does not own or operate a hospital. Each institution is a financially, operationally, and legally independent 501(c)(3) institution and each employs its own faculty and staff. The 17 AHCs are linked contractually to Harvard primarily through affiliation agreements, and Harvard faculty appointments are obtained from specific Harvard schools. As legally and operationally independent entities, the AHCs are, in many respects, both competitive and cooperative with each other. Each institution has an independent IRB (or IRBs), many institutions have exceptionally robust human research participant protection programs (HRPPs). Many, but not all, AHCs are accredited by the Association for the Accreditation of Human Research Protection Programs, Inc. (AAHRPP).

Prior to 2008, there were no systematic shared standards or cooperative operations among the institutions. Across Harvard and its AHCs, over 15,000 research protocols are reviewed and approved annually; a significant percentage of these protocols are collaborative projects, engaging investigators across Harvard's affiliated institutions. Traditionally, each collaborating investigator engaged his/her respective IRB to review and approve a protocol, resulting in inefficiency for both IRBs and investigators. Even when institutions engaged in IRB reliance, single, one‐off, individual authorization agreements (IAAs) were utilized for individual protocols. Each IAA was managed individually; each set of terms and conditions was reviewed and negotiated; signatures of appropriate institutional officials were required. Occasionally, substantive issues were identified that required further negotiations and compromise. While some IAAs were completed in a short time (i.e., 1–2 weeks), others took much longer to finalize (i.e., months), a frustrating delay among institutions that frequently collaborated with each other.

In May 2008, HMS received the NIH CTS award, which provided a mandate and obligation to bring together the teaching hospitals and other affiliated institutions. The CTSA brought together the affiliated entities, including four NIH‐funded General Clinical Research Centers (GCRCs): and their satellites. Together, there were six supporting clinical pathology laboratories. In the context of this highly decentralized regulatory environment of C/T research at Harvard (along with the CTSA mandate), the CTSA brought together the affiliated entities and offered meaningful opportunities for collaboration, process improvement, reorganization and simplification. A master IRB reliance agreement was identified as a primary means to more broadly enable research studies across Harvard Catalyst institutions while eliminating the need for case‐by‐case IAA negotiations.

Creating the framework for the master IRB reliance agreement

While Harvard Catalyst is comprised of over 20 separate legal entities, it was the former GCRC institutions and their satellites—representing the nine institutions with the largest number of protocols—that worked on establishing the prototype MRA. Other CTSAs were contacted to obtain and review existing reliance agreements and to learn of existing processes. The MRA and reliance framework developed out of discussions among the leadership of Harvard Catalyst, the university, the hospitals, and IRBs as well as the institutional attorneys. Anticipating future expansion, this cohort reported progress to, and obtained feedback and insight from, the Harvard Catalyst institutions that were not among the initial signatories.

As part of the early discussions, IRB leadership considered creating a single IRB or “Central IRB” for all C/T review. The concept was eliminated for several reasons, including consideration for the autonomy (and pride) of the participating institutions; the considerable size of the mandate (15,000+ protocols); diversity of expertise (e.g., some existing IRBs specialized in psychiatric illness, others in pediatrics, prisoner research, international research, etc.); perceived institutional liability; and an existing culture of ownership and independence. Instead, a model was sought that emphasized flexibility and autonomy and respected the independence and expertise of the participating institutions and IRBs while also respecting the initial cautiousness with which the institutions approached collaboration. While the group considered limiting the scope of the reliance agreement to minimal risk studies as a possible means to speed adoption, they rejected such limitation, instead choosing a framework that embraced the entire T0‐T4 spectrum, and thus enabling reliance in the translation of basic scientific discovery to humans, patients, practice, and broad population health.

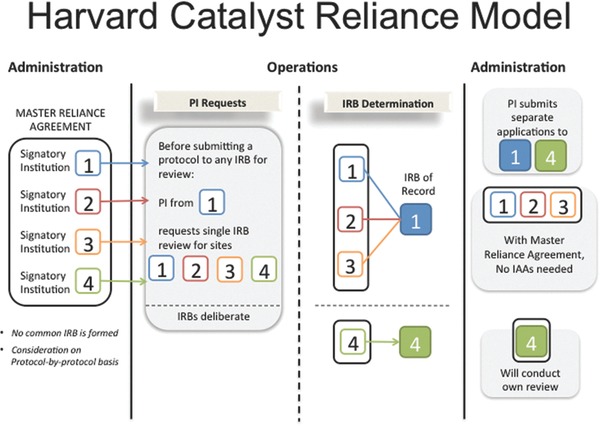

The resulting MRA facilitates review of all human subjects research, from expedited and minimal risk social behavioral research to interventional biomedical trials, from Phase I to postmarket approvals. Furthermore, the scope of the MRA is not limited to only new protocols; it may also be applied when adding a new site to an existing protocol. The model does not mandate reliance but allows any individual signatory institution—without shared governance but by agreement—to cede review to an IRB of another signatory institution, if desired, on a protocol‐by‐protocol basis (Figure 1 ). With a master agreement, any two participating IRBs may agree to review or rely—and elect to do so without negotiating and signing additional IAAs. The MRA permits the greatest flexibility of use and access with minimal administrative burden. Any participating IRB may serve as the reviewing IRB (also termed the IRB of record) for a given project. Any investigator, regardless of seniority, may request ceded review and may do so before any full protocol application is written.

Figure 1.

Harvard Catalyst reliance model.

The agreement enables various reliance options. In the most common and obvious situation, one or more collaborating, signatory institution(s) may choose to rely on the IRB of another signatory institution participating in the study. However, the agreement allows for other kinds of reliance as well. For example, a single signatory institution (with no collaboration) may choose to utilize another signatory institution's IRB; this method could be utilized in situations in which the participating institution, but not the reviewing IRB, has an institutional financial or other conflict of interest (COI; as for instance, when the participating principal investigator is the institutional official). An institution that has a federal‐wide assurance (FWA) but does not have a convened IRB may also utilize the MRA. Another use of the agreement occurs when two or more collaborating, signatory institutions choose to utilize a reviewing IRB of another signatory institution not participating in the study. This latter instance is particularly useful when the specific expertise of the IRB of a nonparticipating institution is most appropriate (due to composition of membership or board expertise) for review of the study (e.g., prisoner research, international research).

Critical components: aligning language, process, and procedures

Respecting each signatory's legal status, the MRA does not mandate IRB reliance; rather it navigates the necessary regulatory, business, and legal terrain to allow reliance as appropriate. Critical to acceptance and practical utilization, the agreement specifies roles and responsibilities of each participating institution and IRB. Defined within the MRA document are regulatory terms and institutional requisite representations, eliminating the need for supplemental paperwork or memoranda; processes and responsibilities are also explicitly defined. To ensure that research is conducted with the highest standards of scientific design and participant safety, the MRA is supported by standard operating procedures (SOPs) and defined roles and responsibilities.

The development of the MRA (and expansion of signatories to the MRA) required significant discussion and interpretation in three central areas: (1) common language and regulatory interpretation; (2) common processes; and (3) common SOPs. Becoming signatory to the MRA requires harmonized understanding, acceptance, and adoption of the terms of the agreement, as discussed below. While many institutions find it simplest to apply these policies and processes to all research regardless of whether the MRA is in use, such application is not a mandate of the agreement.

Common Language and Regulatory Interpretation

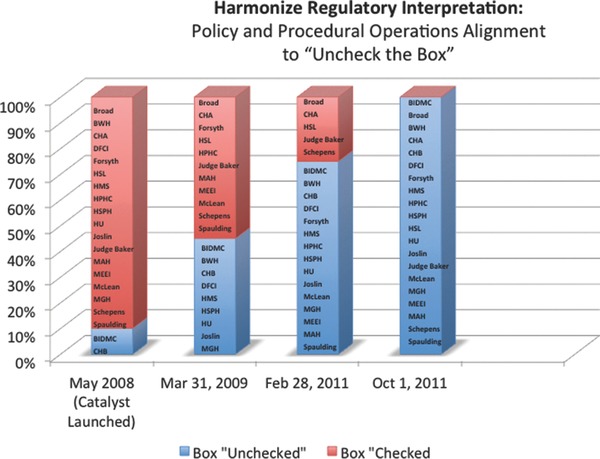

Common language and regulatory interpretation, specifically in four key areas, ensure consistency of approach among signatory institutions (Table 1 ). First, an institution must not elect the 4(b) option on the federal‐wide assurance (FWA) application agreeing to voluntarily apply each subpart of 45 CFR 46 to all human subject research (i.e., they must “uncheck the box” on their individual FWA). Institutions receiving federal funds for human subjects research must provide the Office of Human Research Protections (OHRP) with their written assurance that they will comply with all federal regulations directed at protecting human research participants. This commitment means that institutions can be held accountable by OHRP for any noncompliance with the regulations governing IRBs.7 Institutions that make the 4(b) election commit to applying the federal regulations to all research, independent of funding source; institutions that do not elect the 4(b) option maintain flexibility in applying federal human subjects protection requirements to research that is not federally funded. In multisite research, consistency in this regulatory application across collaborating institutions is particularly important as it ensures that one institution is not required to report on another institution when such report would not otherwise be necessary. Concurrent with the commitment to decline the 4(b) election, institutions are asked to create a policy clarifying that “unchecking the box” does not eliminate the ethical requirement for IRB review of human subjects research but rather places the responsibility for oversight of nonfederally funded and unfunded research with the institution. Furthermore, the recommended policy suggests reporting of noncompliance to the highest institutional official and retains the ability, by agreement, to report to OHRP for nonfederally funded research (Figure 2 ).

Table 1.

Common language and regulatory interpretation required in the MRA

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 2.

Harmonizing regulatory interpretation: policy and procedural alignment to “uncheck the box.”

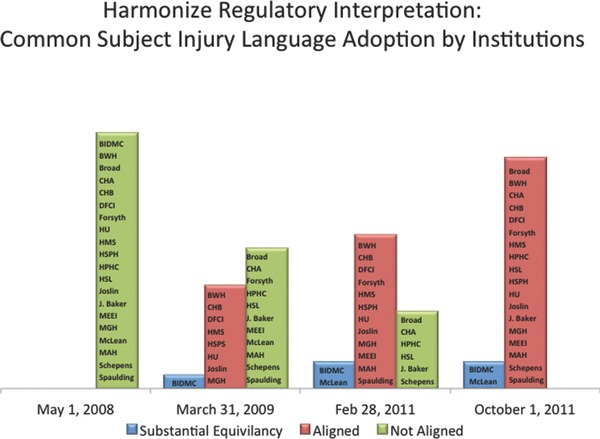

Second, harmonization of subject injury language ensures that the language of the informed consent does not compel one institution to provide treatment or payment by another institution without prior agreement. During development of the agreement, institutions recognized that even if the agreement and model were successfully designed, additional delays were anticipated if negotiations for compensation for injury continued into the consent form. To prevent additional delays, the institutional attorneys developed two sets of common subject injury language: one for entities covered by the Health Information Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA), such as hospitals and business associates (“covered entities”), and another for noncovered entities, such as universities. Participating institutions take different approaches to incorporating the language into their informed consent model language. Some update all of their consents to reflect the common language; others use the language only for studies subject to the reliance agreement. For institutions wishing to retain their own subject injury language, the signatories instituted a process to determine whether the proposed language was “substantially equivalent” to the common language (Figure 3 ).

Figure 3.

Harmonizing regulatory interpretation: adoption of common subject injury language.

Third, minimal insurance requirements ensure signatories have consistent, appropriate, and sufficient insurance coverage for human subjects research. Since the original nine signatory institutions were all insured by the same insurance company, the original agreement included no insurance provision. When the agreement expanded to the next 11 signatories, many with different insurance companies, these minimal insurance requirements were added.

Finally, because not all collaborating institutions are covered by HIPAA regulations, the MRA requires that all institutions—whether a covered entity, a hybrid entity or an uncovered entity—be able to comply with HIPAA, HITECH and related privacy laws when reviewing for another entity.

Common Processes

In addition to common regulatory interpretation, seven critical common processes ensure consistency of approach among the institutions (Table 2 ). First, recognizing that collaborative research may originate or be conducted at any participating institution, it is imperative to have clarity as to which IRB has jurisdiction over the research. Although faculty members may have appointments at multiple institutions, a faculty member is usually considered “an employee” or a “work force member” of only one institution and therefore under the jurisdiction of one primary employer. Thus, the investigator must work with the IRB of their primary employer to establish whether a protocol will be reviewed or ceded; such a policy eliminates “IRB‐shopping” by the individual investigator. Furthermore, as a first assumption—but subject to discussion—the institution of the overall principal investigator of the study is assumed to be the reviewing IRB. That IRB determines whether a study is appropriate for cede review and whether they are the most appropriate IRB to execute that function.

Table 2.

Seven critical common processes required in the MRA

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Second, the framework generally requires collaboration with both overall and site investigators (unless an investigator is already cross‐credentialed at another institution or the reliance agreement is utilized to access “expert” IRB review as discussed above). For multisite research conducted under the MRA, the overall investigator is ultimately responsible for the conduct of the research at all sites but works with site investigators who are responsible for the conduct of the research at their individual sites. The site investigators report to the overall investigator who retains the responsibility for reporting to the reviewing IRB.

Third, a compelling issue for the assurance of cooperative trust among the institutions was the assurance of a quality program. Many, but not all, of the signatory institutions' human research protections programs have applied for and been accredited by the AAHRPP, interpreted as prima facie evidence of quality. Nonaccredited institutions are invited and encouraged to apply for AAHRPP accreditation. Non‐AAHRPP accredited signatories are asked to perform a self‐assessment utilizing the OHRP Quality Assurance Self‐Assessment Tool.7 The OHRP program is intended to help an institution evaluate and improve the quality of its human research protections program. In addition, these institutions are asked to request from OHRP an in‐depth quality assessment consultation. Harvard Catalyst leadership works with institutions to ensure compliance, providing resources (e.g., sample policies, QA/QI consultations) and sharing best practices to support the self‐assessment and in‐depth review.

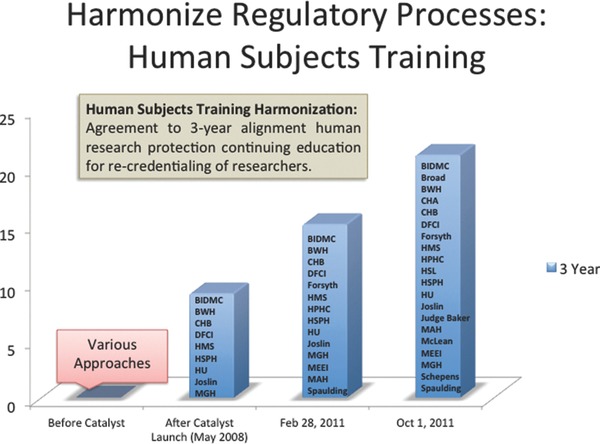

Fourth, institutions agree to a common 3‐year expectation for investigator continuing education (CE) in order for an individual to retain their credentials to participate in clinical research. Initially each of the HRPPs had different expectations for validation of investigator competence or certification and for continuing education: some institutions had no CE requirement for their research faculty; some had 2‐ or 3‐year requirements. Importantly, all institutions also agree to accept one another's trainings. While individual training is accepted, the preferred program is the Collaborative Institutional Training Program (CITI training) offered by the University of Miami (https://www.citiprogram.org) (Figure 4 ).8

Figure 4.

Harmonize regulatory processes: Human Subjects Training.

Fifth, collaborating institutions are well aware that IRB review and approval does not constitute the entirety of the requirements for commencement of a study. Therefore, to participate in the agreement, each IRB must be able to delay activation and initiation of a study until other processes, such as local institutional contract negotiations, are complete. This provision recognizes that IRB offices—but not the IRB itself—have become the gatekeepers for numerous institutional processes. For example, many IRB offices oversee COI determinations related to human subjects research or clinical trial agreement activation. Sometimes the most time‐consuming requirement of clinical trials is the negotiation and execution of the clinical trial contract agreement. The provision acknowledges that the reviewing IRB could review for studies that have activation criteria that differ by site.

Sixth, in drafting the MRA, participating institutions wished to ensure that serious or unanticipated problems, adverse events, and deviations would be reported and managed appropriately; this provision proved to be the most challenging to negotiate. The participating institutions' attorneys were instrumental in suggesting and drafting a framework that followed the investigation lifecycle: from discovery to investigation to determination of level of noncompliance to executing responsibilities for reporting. Particularly sensitive information may require a specific confidentiality agreement or even joint defense agreements. The MRA includes specific language that ensures that the institutions report to the reviewing IRB any relevant issue, with appropriate provisions for confidentiality, oversight, and timeliness. The reviewing IRB is the institution responsible for reporting. The relying institution is provided with opportunity to review and comment. Nothing in the MRA prevents the relying institution from making its own reports.

Finally and importantly, the MRA encompasses a process to allow investigators to request reliance. In this model, investigators are able to request single IRB review before completing all of the individual IRB forms and paperwork and formally submitting a protocol. After piloting an initial paper request document, an online, form‐based system was created—The Harvard Catalyst IRB Cede Review Request System. This system allows investigators to request reliance and IRBs to review such requests and make an appropriate determination, which the reviewing IRB logs into a searchable database. Investigators may also submit a request to add an additional site (or sites) to an existing, approved protocol. In this case an investigator submits an application form describing the new site's involvement and referring the IRBs to the existing protocol for detailed information about the approved study; once the institution(s) agree to cede review an amendment would be submitted to the reviewing IRB. Since each institution has different forms and systems for IRB protocol applications, determination of reliance before submission saves significant investigator time and effort.

Common SOPs

Each participating institution agrees to five common policies and SOPs (Table 3 ). All SOPs are intended to facilitate a bi‐directional collaborative process between the reviewing IRB and relying institutions. “Best practice” policy language is made available for adoption and sample policies of other participating institutions are shared to demonstrate how other institutions have integrated specific provisions into their own IRB policies. Institutions may either adopt drafted language or incorporate the spirit/elements of the Harvard Catalyst SOPs into existing policies.

Table 3.

Common standard operating procedures (SOPs)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The first recommended SOP is a policy to note that participating institutions may enter into joint review arrangements, rely upon the review of another qualified IRB, or make similar arrangements for avoiding duplication of effort. The policy should articulate the use of a reliance agreement where the institution relies on another institution or another institution seeks to rely on it, and should mention that the MRA may be utilized under this policy.

Second, a policy for audits (Audit SOP) delineates the respective rights of access and duties of both reviewing and relying sites. The Audit SOP is intended to encourage all participating institutions to perform both not‐for‐cause and/or for‐cause audits. The reviewing IRB has the right and responsibility to conduct investigations, and although the Audit SOP assumes that the auditing institution would also be the reviewing institution (and in most cases, it is), the SOP is not intended to serve as a requirement nor to preclude the relying/nonauditing institutions from conducting their own independent audits, from reasonably requesting a copy of the already performed audit, or from submitting their own reports. While directed/for‐cause audits are generally triggered from the “ground up” (the site PIs generally report to the overall PI, who then reports to the reviewing IRB, as well as to the relying institution(s) if he/she so chooses), to date MRA audits have primarily stemmed from an organization's routine onsite review function.

Third, because the agreement mandates institutions “uncheck the box,” each signatory institution must develop a policy for the reporting of serious adverse events (SAEs) and unanticipated problems for research not funded by the federal government. Many signatory institutions adopt provisions to report such events to the institutional official and the president or CEO of the institution. The agreement only mandates that such a policy be established; it does not dictate institutional practices or assign reporting roles within the institution. From a framework perspective, the agreement specifies who is responsible (the reviewing IRB or the relying institution) when reliance is in place, but it is up to each institution to determine the responsible party; institutional autonomy is preserved.

Two final policies have taken longer to draft: the Data Protection and Information Incident SOP and the COI SOP. The Data Protection/Information Incident SOP establishes detection and reporting of potential research information breach scenarios within the MRA. The need for this SOP arises from the increasing importance of data privacy and security in research generally, as well as the need to underscore institutions' individual ongoing compliance obligations with respect to information risk beyond the MRA. The SOP delineates the duties when managing a data breach in research conducted under an MRA in the context of reliance when there is a reviewing and relying institution.

The COI SOP is multifaceted. First, the institutions adopt a COI “zero dollar” disclosure approach and the IRBs amend their applications to capture all conflicts, even if in compliance with regulations and faculty policies. Second, the COI SOP delineates that the home institution/relying institution will reduce, eliminate, or manage any identified conflict according to its own policies and procedures. If not preidentified by the relying institution, the reviewing IRB will identify the conflicts through its IRB forms. An identified COI is returned to the relying institution, which reports the reduction, elimination or management plan to the reviewing IRB who then has the authority to determine if the plan is acceptable. If the reviewing IRB determines the management plan is not acceptable, the reviewing IRB will promptly inform the relying institution and the research will not be eligible for review unless the relying site develops a plan acceptable to the reviewing IRB—generally within thirty (30) days. The reviewing IRB always retains the authority to impose additional provisions to manage a COI, and to make the conflict management requirements more stringent or restrictive than those implemented by the relying institution.

The alignment of policies and procedures has advantages for investigators, administrators, and institutions. Prior to the introduction of common policies and processes, each investigator was required to comply with a variety of different—often trivially different—professional expectations and processes for documentation. The drafting of the MRA led to alignment of such requirements. Administrators similarly heralded alignment of reasonable, but nonnegotiable, processes. The process of collaboration also provoked some institutions to define or redefine their (1) definition of IRB jurisdiction (e.g., appointment versus employment), (2) internal policies regarding who could serve as a principal investigator and the roles and responsibilities of that investigator, and (3) process for activation and initiation of a trial, including contract negotiation, nursing and pharmacy communication, (4) need for QA/QI processes, etc. These collaborative efforts have strengthened the trust, communication, and multidirectional voluntary assistance among the participating institutions and simplified burdensome processes for administrators and investigators.

The “reciprocal” master reliance agreement: a scalable model

Initially signed by nine Harvard and Harvard‐affiliated institutions, the first Harvard Catalyst MRA was executed on March 31, 2009. In 2012, the agreement was amended and expanded to include an additional eleven Harvard Catalyst institutions, bringing the total number of signatory institutions to twenty Harvard‐affiliated institutions (Table 4 ).

Table 4.

Signatories to the MRA

| Initial signatories (2009) | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center | Broad Institute | Tufts Medical Center | Boston University – Charles River Campus |

| Brigham and Women's Hospital | Cambridge Health Alliance | Tufts University Health Sciences Campus | Dartmouth College |

| Boston Children's Hospital | The Forsyth Institute | Tufts University Medford/Somerville Campus | New England Baptist Hospital |

| Dana‐Farber Cancer Institute | Harvard Pilgrim | Massachusetts Institute of Technology | |

| Harvard Medical School* | Hebrew Rehabilitation Center | University of Southern California | |

| Harvard School of Public Health | Judge Baker Children's Center | Health Sciences Campus | |

| Harvard University Faculty of Arts and Sciences† | Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary | University of Southern California | |

| Joslin Diabetes Center | McLean Hospital | University Park Campus | |

| Massachusetts General Hospital | Mount Auburn Hospital | University of Rhode Island | |

| Schepens Eye Research Institute | |||

| Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital Network |

*Reviewing also for the Harvard School of Dental Medicine.

†Reviewing for all 10 of University's nonmedical professional schools.

Since its initial execution and subsequent expansion, interest in the MRA has grown both nationally and regionally. We have shared the MRA model and agreement widely and provided individual consultations to more than 30 CTSA and non‐CTSA groups across the country; these institutions have used the MRA in a number of ways. Several institutions have referred to the MRA in drafting their own interinstitutional agreement or amended the contractual terms to expand or delete elements in their agreement. Others have used the agreement to benchmark against their own model and adopted several policies based on the MRA templates. Some have used the MRA‐model as a guide for identifying appropriate metrics to capture to aid in assessment and used the agreement to develop a web‐based reliance agreement toolkit. Overall, the MRA has provided a common starting point that was previously elusive in independent authorization agreement discussions. Information about the MRA is available via the Harvard Catalyst website

(http://catalyst.harvard.edu/programs/regulatory/reliance.html), where visitors may also request a copyof the agreement.

In September 2012, when the New England Regulatory Consortium (now comprised of the CTSAs of Harvard, Boston University, Dartmouth College, Tufts University, University of Massachusetts, and Yale University) first convened, the group endeavored to develop a regional IRB reliance agreement and endorsed the Harvard Catalyst Reciprocal Common IRB Reliance Agreement as a potential model for the proposed regional agreement. Subsequent group review of provisions, policies, and practices covering terms and conditions of the MRA model, including: (1) IRB authority; (2) the obligation to report adverse events, research subject complaints and noncompliance; (3) the timeliness and form of communication; (4) oversight of investigator performance; (5) information from data safety monitoring plans; (6) liability; (7) use of name; and (8) access and reciprocal expectations of access, helped institutions to fully appreciate the details of the agreement.

Institutions within the New England Consortium and beyond have since signed the MRA without modification. In 2013, the MRA expanded to include three signatories affiliated with the Tufts University CSTI. In 2014, Boston University—Charles River Campus, New England Baptist Hospital, and Massachusetts Institute of Technology signed‐on to the agreement as well, and the MRA began expanding beyond Massachusetts with the added participation of Dartmouth College in New Hampshire, the University of Southern California, and University of Rhode Island (Table 4 ). We expect to see continued expansion as more than a dozen institutions, not all CTSA‐affiliated, actively consider signing the MRA.

Expansion of the MRA to include the New England CTSAs and institutions outside of New England was discussed at length with the existing signatories to the agreement. While not stated in the agreement, the addition of new sites is approached in the spirit of joining a treaty. New sites join the agreement without the formal approval of other signatories so long as the new signatory agrees to the three central areas outlined above: (1) common language and regulatory interpretation; (2) common processes; and (3) common SOPs. Once an institution executes the requirements, they may “sign‐on” and join the agreement.

The reliance agreement framework allows new sites to participate simply, as the agreement defines the roles and responsibilities of each party. New institutions join through a simple amendment termed a “Joinder Agreement,” an agreement that allows for specific issues to be addressed. For example, the MRA is currently silent regarding state law (as the original signatories were all within Massachusetts). The joinder agreement for non‐Massachusetts institutions includes a statement addressing local conditions and state law such that the institution (when relying on another IRB under the MRA) remains responsible for conducting the analysis of any specific local conditions and requirements of state or local laws, regulations, policies, standards (social or cultural) or other factors applicable to the research. Additionally, while adoption of uniform subject injury language for informed consents and mandated insurance minimums have not been abandoned they have proven to be a challenge in the expansion process. New sites consider adoption of the uniform language but may opt for “substantially equivalent” language—an option more often utilized by new signatories. Further, new signatories include state institutions and smaller clinics and thus new insurance language may need to be considered. As institutions and IRBs gain experience and comfort with the agreement, signatory institutions have been more willing to consider revisions or flexibilities in the agreement and process.

DISCUSSION

The Harvard Catalyst MRA addresses the regulatory and business decisions within the document with clarity and definition. The legal document and framework delineates roles and responsibilities, defines decision making authority, and allows reliance to be determined based on the merits of a given study. Thus, resource‐intense efforts shift to the front—before an investigator submits a multisite study to numerous IRBs—and allows the IRBs to determine in advance which IRB is best suited to the legal and ethical responsibilities for reviewing, approving, monitoring, and conducting a specific study.

The Harvard Catalyst MRA differs from many other reliance models in design, scope, flexibility, and access. The MRA does not create a centralized IRB (as with the NINDS NeuroNext network) nor does it establish a single IRB coordinating center or enable concurrent, shared, or facilitated review (as with Vanderbilt University's IRBshare). The MRA does not mandate a single system for regulatory review of C/T research but rather allows an institution to choose to completely cede the review of a research protocol to another reviewing IRB, as appropriate. To reduce investigator burden, the MRA allows investigators to request reliance before submitting any IRB paperwork or when adding a site (or sites) to an existing protocol.

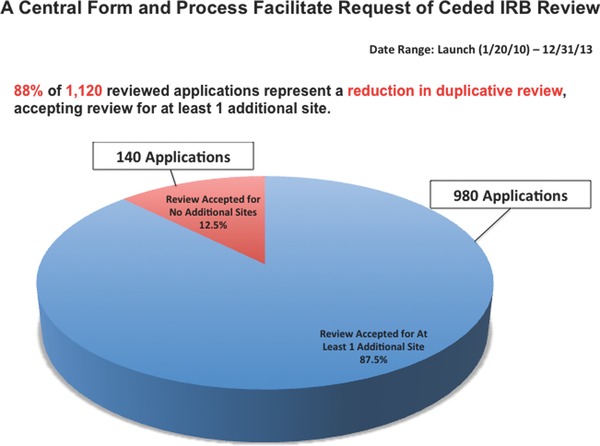

The establishment and expansion of the MRA has provided the proof‐of‐concept that an interinstitutional IRB framework can be designed, built, and implemented by institutions and IRBs seeking efficiencies in ethics review for multisite research. From 2010 through 2013, Harvard Catalyst‐affiliated investigators submitted over 1,100 requests for ceded IRB review. Close to 90% of the applications were approved for reliance, in that the reviewing IRB agreed to review for at least one additional institution (Figure 5 ). We have seen a steady increase in the number of successful applications and a consistent trend towards willingness to engage in reliance (Table 5 ). Together, the integrated system—and expansion beyond Harvard to New England and now beyond the local geographic community—has shown the MRA to be a viable option for a wide range of studies, demonstrating its applicability to research networks and systems beyond Harvard.

Figure 5.

A central from and process facilitate request of ceded IRB review.

Table 5.

Successful applications for IRB reliance (at least one site cedes review; reviewing IRB agrees to review for at least one additional site)

| No date* | 2011† | 2012 | 2013 | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Applications approved for reliance‡ | 186 | 175 | 294 | 325 | 980 |

| Total reviewed applications | 217 | 200 | 333 | 370 | 1,120 |

| Percentage of successful applications for reliance | 86% | 88% | 88% | 88% | 88% |

*Between launch of request system in January of 2010 and release of v2.0 on March 17, 2011.

†From March 17, 2011 onward (release of v2.0 with log data for system decision date).

‡Includes application data for sites nonsignatory to the MRA; the request system enables the inclusion of outside sites for which a separate IAA would be required, should the IRB agree to cede review.

The transition from individual review to reliance has been a gradual one. Initially, institutions were concerned about the quality of external review and fearful of legal and regulatory liability should the reviewing IRB fail to execute its oversight functions appropriately. With time, and clear definition of the administrative functions, roles, and responsibilities of the reviewing IRB and the relying institution, a culture of trust and communication developed among institutions and individuals. The IRB offices appreciate the benefits of harmonization of process and standardization of terms used in both informed consent documents and contracts. This master agreement provides a potential pathway to reduce the burden and inconsistency of case‐by‐case review and negotiation, and by offering a pathway to single or consolidated IRB review the MRA may aid in lowering barriers to cooperative and multisite research. The impact of the NIH CTSA in spurring such inter‐institutional collaboration in general, and policy reforms in the regulatory domain in particular, cannot be overstated.

While the MRA eliminates the need for separate IAAs and individual negotiation and documentation and streamlined initial and continuing review hold potential benefit for institutions, IRBs, and investigators, we recognize that the MRA introduces another set of burdens. An IRB Administrator or other individual(s) with sufficient expertise and authority must review investigator requests and determine the appropriateness of reliance on a case‐by‐case basis. This review requires these individuals to clearly communicate with their counterparts and with investigators to ensure that the nature of the research is understood before a determination is made. Thus, while the MRA spares the full board of the IRB from engaging in duplicative review, the IRB and its staff take on increased responsibility. In addition, the MRA benefits from central support and infrastructure provided through Harvard Catalyst. For example, the IRB Cede Review Request System was developed to support the use of the MRA among Harvard Catalyst institutions, and the development, maintenance, and expansion of such a system requires significant resources, financial and otherwise.

In bringing new signatories to the agreement we have found the preparation time to sign‐on to vary depending upon the maturity, development, and/or resources of a given institution and IRB, as well as the robustness of existing institutional/IRB policy. As the agreement expands, we anticipate that modifications and improvements may be made to the document and process and, in the spirit of the MRA's inception, such modifications would be reviewed and agreed to by consensus. The Harvard Catalyst signatories are brought together on a monthly basis through the Harvard Catalyst Regulatory Foundations, Ethics and Law Committee (a group comprising representatives from the Human Research Protection Programs of Harvard Catalyst's participating institutions, among others); a listserv has been established to enable clear and timely communication with all MRA signatories, including those outside Harvard Catalyst and an MRA Toolkit is under development. As the MRA expands, we recognize that the governance and communication model will need to grow as well to meet the changing make‐up and shifting needs of the group.

To date, we have focused on the operational elements of the MRA's model of reciprocal reliance and measured usage of the option to engage in reliance. We have not, as yet, focused on explicit measurement of the model's impact in terms of the efficiency of protocol review by the reviewing IRB, enhancement of participant protections, or measured reduction in administrative burden. Whether the MRA will translate into cost savings, increased accrual, and shorter time to first or last enrollee, or more rapid publication is yet to be determined. These deeper impact measurements will require cooperative access to, and analysis of, data from the research administration systems of the signatory institutions. National definitions of data elements and of comparable measures would assist in this regard.

The Harvard Catalyst MRA supports a model of reciprocity, allowing any signatory institution to rely on another IRB's review as appropriate. Rather than creating a new, centralized system for regulatory review of research, the MRA incorporates the capabilities and processes of each participating entity in support of a robust cooperative and integrated system. Importantly, the MRA has proven to be adaptable and scalable as its signatories have expanded beyond CTSA and state lines. The agreement and framework provide a path to reliance that clearly delineates the roles and responsibilities of the reviewing IRB and relying institution(s) and respects local expertise, institutional autonomy, and accountability. With a strong foundation of law and ethics, the MRA seeks to decrease administrative burden, support efficiency, and ensure robust human subjects protections.

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the Harvard Catalyst Regulatory Foundations, Ethics and the Law Committee and the New England Regulatory Consortium for their commitment to the development, success, and expansion of the MRA.

Sources of Funding

This work was conducted with support from Harvard Catalyst. The Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (8UL1TR000170–05 and 1UL1 TR001102–01 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS) at the National Institutes of Health, with additional support from Harvard University and its affiliated academic healthcare centers).

References

- 1. Menikoff J. The paradoxical problem with multiple‐IRB review. N Engl J Med 2010; 363(17): 1591–1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Emanuel EJ, Wood A, Fleischman A, Bowen A, Getz KA, Grady C, Levine C, Hammerschimdt DE, Faden R, Eckenwiler L, et al. Oversight of human participants research: identifying problems to evaluate reform proposals. Ann Inter Med. 2004;141(4): 282–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pritchard IA. How do IRB members make decisions? A review and research agenda. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics 2011; 6(2): 31–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Stark L: Behind Closed Doors: IRBs and the Making of Ethical Research. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Drezner MK, Cobb N: Efficiency of the IRB review process at CTSA‐sites. Presented at CTSA Clinical Research Management Workshop; 2012. https://ctsacentral.org/sites/default/files/documents/2_drezner.pdf. Accessed August 11, 2014.

- 6. Silberman G, Kahn K: Burdens on research imposed by Institutional Review Boards: the state of the evidence and its implication for regulatory reform. Milbank Quarter. 2011; 89(4): 599–627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. See U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of Human Research Protections Quality Assessment Program. http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/education/qip, Accessed April 15, 2014.

- 8. See Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative (CITI Program) at the University of Miami. https://www.citiprogram.org, Accessed April 15, 2014.