Abstract

Background

Left upper quadrant involvement by peritoneal surface disease (PSD) may require distal pancreatectomy (DP) to obtain complete cytoreduction. Herein, we study the impact of DP on outcomes of cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (CRS/HIPEC).

Methods

Analysis of a prospective database of 1,019 procedures was performed. Malignancy type, performance status, resection status, comorbidities, Clavien-graded morbidity, mortality, and overall survival were reviewed.

Results

DP was a component of 63 CRS/HIPEC procedures, of which 63.3 % had an appendiceal primary. While 30-day mortality between patients with and without DP was no different (2.6 vs. 3.2 %; p = 0.790), 30-day major morbidity was worse in patients receiving a DP (30.2 vs. 18.8 %; p = 0.031). Pancreatic leak rate was 20.6 %. Intensive care unit days and length of stay were longer in DP versus non-DP patients (4.6 vs. 3.5 days, p = 0.007; and 22 vs. 14 days, p <0.001, respectively). Thirty-day readmission was similar for patients with and without DP (29.2 vs. 21.1 %; p = 0.205). Median survival for low-grade appendiceal cancer (LGA) patients requiring DP was 106.9 months versus 84.3 months when DP was not required (p = 0.864). All seven LGA patients undergoing complete cytoreduction inclusive of DP were alive at the conclusion of the study (median follow-up 11.8 years).

Conclusions

CRS/HIPEC including DP is associated with a significant increase in postoperative morbidity but not mortality. Survival was similar for patients with LGA whether or not DP was performed. Thus, the need for a DP should not be considered a contraindication for CRS/HI-PEC procedures in LGA patients when complete cytoreduction can be achieved.

Cytoreductive surgery (CRS) with hyperthermic intra-peritoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) improves survival in selected cohorts of patients with peritoneal surface disease (PSD) from a variety of epithelial malignancies. The extent of the survival benefit is predominantly determined by the completeness of cytoreduction.1–3 Patients with PSD may present with extensive involvement of the splenic hilum and distal pancreas. In such patients, obtaining a complete macroscopic cytoreduction often requires en bloc incorporation of the pancreatic tail into the splenectomy specimen. The impact of distal pancreatectomy (DP) on outcomes of patients undergoing CRS/HIPEC is not well described.

The primary goal of this article was to evaluate the differences in procedure-specific morbidity and mortality after CRS/HIPEC between patients with and without DP, regardless of primary lesion. The secondary goal was to describe the impact of DP on the overall survival (OS) of patients who have undergone CRS/HIPEC for PSD from appendiceal primary malignancies.

METHODS

Institutional Review Board approval was obtained for analysis of a prospectively maintained database of 1,019 CRS/HIPEC procedures performed from 1991 to 2013. Eligibility criteria for CRS/HIPEC included histologic or cytologic diagnosis of peritoneal carcinomatosis, complete recovery from prior systemic chemotherapy or radiation treatments, resectable or resected primary lesion, debulkable PSD, and lack of extra-abdominal disease. All patients had a complete history and physical, tumor markers, and computed tomography (CT) of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis prior to CRS/HIPEC procedure. The CRS/HIPEC procedure was conducted as previously described by our group.4

Data abstracted from the database included patient age, race, sex, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, type of primary malignancy, co-morbidities, R resection status, number of visceral organs removed, and number of anastomoses performed. For those patients undergoing DP, operative reports were reviewed to ascertain method of pancreatic transection, intraoperative drain placement, and pancreatic texture. Outcome variables included morbidity, mortality, readmission, specific complications, and OS. R0 and R1 resections were grouped together as complete cytoreductions. Cytoreductions with residual macroscopic disease were characterized as R2 and subdivided based on the size of residual disease (R2a ≤5 mm, R2b >5 mm and ≤2 cm, R2c >2 cm). Surgical morbidity and mortality were graded according to the Clavien and Dindo classification system.5 Minor morbidity was defined as Clavien and Dindo grade I and II, while major morbidity was defined as Clavien and Dindo grade III and IV. Pancreatic leaks were characterized based on the International Study Group of Pancreatic Fistula (IS-GPF) criteria.6 Since drains were not uniformly placed, the current manuscript captures predominantly clinically significant pancreatic leaks.

Descriptive statistics, including frequencies and percentages for categorical data and means and standard deviations for continuous data, were calculated for those with and without DP. Fisher’s exact tests compared categorical variables and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests compared continuous variables. Multivariate analysis was performed to evaluate whether inclusion of DP significantly affected morbidity after controlling for the patient’s extent of disease and performance status.

OS was calculated from the date of CRS/HIPEC (or first CRS/HIPEC in cases where a patient underwent more than one procedure) to the last known date of follow-up or the date of death. Estimates of survival were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier (product-limit) method. Group comparisons of OS were performed by using the approximate Chi-square statistic for the log-rank test. Statistical significance was defined as a p value <0.05. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

RESULTS

DP was performed as a component of cytoreduction in 61 patients undergoing 63 CRS/HIPEC procedures from 1991 to 2013. Median follow-up was 53 months. Those patients who required DP did not differ significantly from those who did not require DP in terms of age, sex, BMI, or preoperative co-morbidities. However, individuals undergoing DP had a worse preoperative performance status than patients not undergoing DP (26.7 % ECOG 2 or greater vs. 15.3 %; p = 0.028). Preoperative albumin levels were also statistically lower in this group but not to a clinically significant degree (3.6 vs. 3.8; p = 0.04). Likewise, the distribution of primary tumors was significantly different between groups, with the appendix serving as the primary site for 63.3 % of those requiring DP but only 45.9 % of those not requiring DP. Additional patient characteristics are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Patient characteristics

| Characteristic (n = 932) | Non-DP (n = 871) | DP (n = 61) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Female [n (%)] (n = 931)a | 461 (53) | 30 (50) | 0.6899 |

| Age [years; mean (SD)] (n = 932)a | 53 (12.6) | 52 (12.1) | 0.5719 |

| Diabetes [n (%)] (n = 888)a | 79 (9.6) | 8 (13.1) | 0.3701 |

| Heart disease [n (%)] (n = 886)a | 70 (8.5) | 6 (9.8) | 0.6387 |

| Lung disease [n (%)] (n = 887)a | 32 (3.9) | 2 (3.3) | 1.000 |

| BMI [mean (SD)] (n = 836)a | 27.6 (6.1) | 28.0 (5.8) | 0.4588 |

| Albumin [mean (SD)] (n = 894)a | 3.8 (0.6) | 3.6 (0.6) | 0.0464 |

| ECOG performance status [n (%)] (n = 921)a | 0.0282 | ||

| 0/1 | 729 (84.7) | 44 (73.3) | |

| 2+ | 132 (15.3) | 16 (26.7) | |

| Type of primary [n (%)](n = 842)a | 0.0019 | ||

| Appendiceal | 400 (45.9) | 38 (63.3) | |

| Colorectal | 223 (25.6) | 2 (3.3) | |

| Mesothelioma | 61 (7.0) | 5 (8.2) | |

| Ovarian | 61 (7.0) | 4 (6.6) | |

| Other | 126 (14.5) | 12 (20.0) | |

| Resection type [n (%)](n = 920)a | <0.0001 | ||

| R0/1 | 401 (46.7) | 23 (37.7) | |

| R2a | 247 (28.8) | 12 (19.7) | |

| R2b | 112 (13) | 22 (36.1) | |

| R2c | 99 (11.5) | 4 (6.6) | |

| Chemotherapeutic agent [n (%)](n = 927)a | 0.5572 | ||

| Mitomycin C | 712 (82.1) | 53 (88.3) | |

| Carboplatin | 26 (3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Cisplatin | 43 (5.0) | 3 (5.0) | |

| Oxaliplatin | 86 (9.9) | 4 (6.7) | |

| No. of organs resectedb [mean (SD)] (n = 932)a | 2.8 (1.5) | 3.8 (1.4) | <0.0001 |

BMI body mass index, DP distal pancreatectomy, ECOG Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, SD standard deviation

Refers to the number available for this characteristic

Excluding pancreas

DP was associated with more operative blood loss (mean estimated blood loss 1,172 ml vs. 760 ml; p <0.001), more days in the intensive care unit [ICU] (mean ICU stay 4.6 vs. 3.5 days; p = 0.007), and a longer hospital stay (mean hospital stay 22 vs. 14 days; p <0.001). Patients requiring DP as a component of CRS/ HIPEC also sustained a higher 30-day major morbidity than those who did not require DP (30.2 vs. 18.8 %; p = 0.03). However, 30-day mortality was similar between patients with and without DP (2.6 vs. 3.2 %; p = 0.790), as was 90-day major morbidity and mortality (Table 2). Although the percentage of those requiring readmission was greater in those undergoing DP, this difference was not statistically significant (30-day readmission rate 29.2 vs. 21.1 %; p = 0.268). Reasons for readmission amongst those undergoing DP included intra-abdominal abscess (35 %), dehydration (41 %), wound complications (12 %) and pulmonary complications (12 %). When reviewing all CRS/HIPEC procedures (n = 1,019) for specific complications, procedures including a DP were more likely to result in a clinically significant pulmonary effusion (9.5 vs. 2.9 %; p = 0.015), deep vein thrombosis (6.4 vs. 1.7 %; p = 0.030), and postoperative ileus (12.7 vs. 4.2 %; p = 0.007) (Table 3).

TABLE 2.

Postoperative morbidity of CRS/HIPEC procedures (n = 1,019)

| Variable | Time interval (days) | Non-DP (n = 956) | DP (n = 63) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minor morbiditya [n (%)] | 30 | 166 (17.4) | 12 (19.1) | 0.732 |

| 31–90 | 50 (5.2) | 4 (6.4) | 0.5702 | |

| Major morbidityb [n (%)] | 30 | 180 (18.8) | 19 (30.2) | 0.033 |

| 31–90 | 58 (6.1) | 5 (7.9) | 0.584 | |

| Mortality [n (%)] | 30 | 23 (2.6) | 2 (3.2) | 0.79 |

| 31–90 | 16 (1.8) | 1 (1.6) | 1.00 | |

| Readmission [n (%)] | 30 | 166 (21.1) | 14 (29.2) | 0.205 |

| 31–90 | 243 (31.9) | 18 (33.3) | 0.881 | |

| Operation time [h; mean (SD)] | 8.4 (3.1) | 10.2 (3.2) | <0.0001 | |

| Hospitalization [days; mean (SD)] | 14 (16) | 22 (28) | <0.001 | |

| ICU stay [days; mean (SD)] | 3.5 (9.4) | 4.6 (7.9) | 0.007 | |

| Estimated blood loss [ml; mean (SD)] | 760 (775) | 1,172 (701) | <0.001 | |

CRS/HIPEC cytoreductive surgery with intraperitoneal hyperthermic chemotherapy, DP distal pancreatectomy, ICU intensive care unit, SD standard deviation

Clavien and Dindo Grade I–II

Clavien and Dindo Grade III–IV

TABLE 3.

Thirty-day complication pattern in patients undergoing distal pancreatectomy

| Complication | Non DP (n = 956) [n (%)] | DP (n = 63) [n (%)] | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operative | |||

| Re-exploration (all cause) | 69 (7.2) | 7 (11.1) | 0.316 |

| Wound dehiscence | 25 (2.62) | 3 (4.8) | 0.247 |

| Pulmonary | |||

| Respiratory failure | 53 (5.5) | 4 (6.4) | 0.775 |

| Pneumonia | 52 (5.4) | 5 (7.9) | 0.391 |

| Pneumothorax | 12 (1.3) | 1(1.6) | 0.566 |

| Pulmonary effusion requiring thoracostomy | 28 (2.9) | 6 (9.5) | 0.015 |

| Cardiac | |||

| Myocardial infarction | 4 (0.42) | 0 | 1.0 |

| Arrhythmia | 27 (2.8) | 2 (3.2) | 0.699 |

| Gastrointestinal | |||

| Gastrointestinal bleed | 10 (1.05) | 0 | 1.0 |

| Enteric leak, managed non- operatively | 8 (0.84) | 0 | 1.0 |

| Ileus | 40 (4.2) | 8 (12.7) | 0.007 |

| Enterocutaneous fistula | 11 (1.2) | 2 (3.2) | 0.190 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 22 (2.3) | 2 (3.2) | 0.656 |

| Gastroparesis | 2 (0.2) | 0 | 1.0 |

| High-output ostomy | 21 (2.2) | 2 (3.2) | 0.648 |

| Infectious | |||

| Wound infection | 32 (3.35) | 2 (3.17) | 1.0 |

| Abscess, treated with IR- guided drain placement | 55 (5.8) | 6 (9.5) | 0.264 |

| Abscess, treated with antibiotics | 21 (2.2) | 3 (4.8) | 0.181 |

| Infectious diarrhea | 12 (1.3) | 1 (1.6) | 0.566 |

| Non-infectious diarrhea | 15 (1.6) | 0 | 0.618 |

| Bacteremia | 43 (4.5) | 3 (4.76) | 0.759 |

| Urinary tract infection | 41 (4.3) | 5 (7.9) | 0.198 |

| Bacterial peritonitis | 4 (0.4) | 1 (1.6) | 0.274 |

| Renal/urinary | |||

| Acute renal failure requiring dialysis | 15 (1.6) | 3 (4.8) | 0.095 |

| Urinary retention | 17 (1.8) | 0 | 0.618 |

| Hematologic | |||

| Thrombocytopenia | 6 (0.6) | 0 | 1.0 |

| Deep vein thrombosis | 16 (1.7) | 4 (6.4) | 0.030 |

| Pulmonary embolus | 8 (0.84) | 1 (1.6) | 0.438 |

DP distal pancreatectomy, IR interventional radiology

To evaluate whether the excess morbidity in the DP cohort remained significant after controlling for their lower performance status and increased burden of disease, a multivariate analysis was performed. Initial univariate analysis demonstrated that age (p = 0.03), EBL (p <0.001), R resection status (p <0.001), inclusion of DP (p = 0.03), number of organs resected excluding the pancreas (p <0.001), and number of anastomoses performed (p <0.001) were significant predictors of 30-day morbidity. However, the final reduced multivariate model signified that DP was not a significant predictor of 30-day major morbidity (p = 0.15) after controlling for age (p = 0.01), R resection status (p = 0.002), and number of organs resected (p <0.001).

Of the 63 CRS/HIPEC procedures that included a DP, 55 % were transected with the use of a TA or GIA stapler, 34 % were transected with a stapler and then over-sewn, and 11 % were transected with electrocautery and then over-sewn. Intraoperative left upper quadrant drains were placed in 45 % of these patients.

Thirteen of these procedures (20.6 %) were complicated by pancreatic fistula (PF). Two (15.4 %) such leaks were Grade A leaks, both of which resolved within 12 days of their diagnosis. The remaining PF were Grade B and C leaks. There were no statistical differences in the method of pancreatic transection (p = 0.49) or intraoperative left upper quadrant drain placement (p = 0.18) between those who did and did not develop PF, nor were there statistically significant differences between those with and without PF with respect to their preoperative albumin level (3.7 vs. 3.59; p = 0.42), number of organs resected, excluding pancreas (4.7 vs. 4.5; p = 0.67), or ECOG performance status (15.4 % ECOG 2+ vs. 30.6 % ECOG 2+; p = 0.27). Three patients with PF (23.1 %) presented with pancreatic ascites and were treated with reoperation and drainage. Four (30.8 %) presented with peripancreatic abscesses and were treated with interventional radiology (IR)-guided percutaneous drain placement. Two (15.4 %) presented with left hydrothorax and elevated amylase levels in the pleural fluid. Both were managed with a tube thoracostomy. Three patients (23 %) required parenteral nutrition. Three patients (23 %) with pancreatic leak died; however, two of these patients also developed concurrent enteric leaks. The median time to leak resolution among survivors was 35 days.

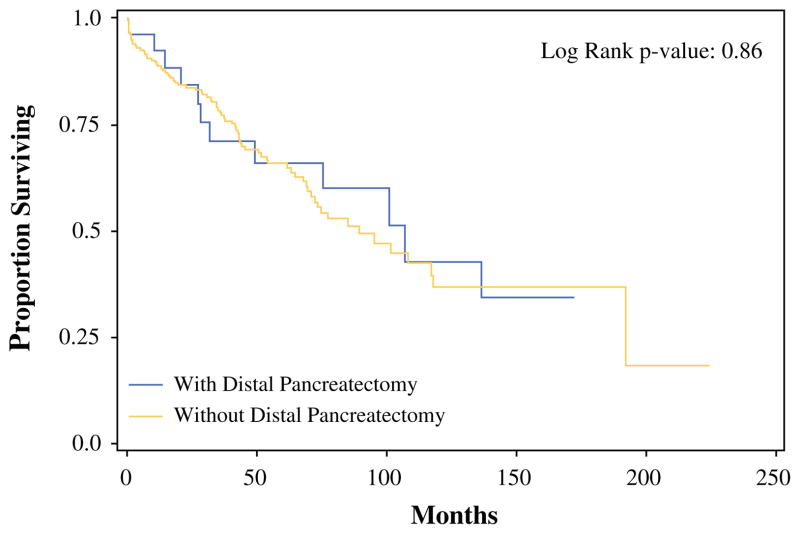

Survival analyses were confined to patients with similar primary lesions due to the effect of tumor biology on survival outcomes. Median OS was similar for all patients with low-grade appendiceal primary malignancies (LGA) following CRS/HIPEC regardless of the inclusion of a DP (106.9 months with DP vs. 84.3 months without DP; p = 0.864) (Fig. 1). Subgroup analysis for patients with LGA based on the ability to achieve complete cytoreduction (R0/R1) could not be performed because the median survival was not reached. In fact, each of the seven patients with PSD due to LGA who received a complete cytoreduction inclusive of a DP was alive at the conclusion of the study period, with a median follow-up of 11.8 years.

FIG. 1.

OS of low-grade appendiceal patients with and without DP. Median OS without DP: 89.4 months; median OS with DP: 106.9 months. OS overall survival, DP distal pancreatectomy

DISCUSSION

The survival benefit from CRS/HIPEC procedures is directly related to the completeness of cytoreduction.1–3,7 Since pancreatectomy is associated with significant morbidity, DP is typically not performed during CRS/HIPEC. Therefore, when effacement of the splenic hilum by tumor deposits makes isolated splenectomy neither oncologically sound nor technically feasible, the surgeon is faced with the dilemma of either aborting the case or proceeding with cytoreduction that will include a DP and splenectomy. A small number of prior studies have investigated the morbidity and mortality of DP during CRS without chemoperfusion in metastatic ovarian cancer.8–10 The current study represents the largest series of PSD patients to undergo synchronous CRS/HIPEC with DP.

The presented analysis demonstrates that the addition of DP to CRS/HIPEC results in a significant increase in perioperative morbidity but not in overall mortality. More specifically, major morbidity and length of hospital stay were nearly double in the DP cohort. Since DP was performed for increased volume of disease, it is not surprising that those requiring DP presented with worse performance status and required a more extensive operation, as indicated by longer operative times, higher blood loss, and greater number of organs removed at the time of CRS/HIPEC. Indeed, when controlling for this higher burden of disease during multivariate analysis, the inclusion of DP no longer remained a significant predictor of 30-day major morbidity, indicating that more extensive cytoreduction contributed to overall worse perioperative outcomes.

Previous reports have demonstrated no significant role in the method of pancreatic transection upon PF development, and the results of this study were no different in that regard.11–16 Additionally, factors known to predispose individuals to PF, such as albumin level, were not significantly different between those who did and did not develop PFs in this study. In sum, PF complicated 20.6 % of DP procedures in this study. This is in agreement with multiple prior studies, which indicate that closure of the pancreatic stump fails in 12–31 % of non-PSD patients undergoing DP.17–20 Thus, chemoperfusion in the current study was not associated with a clinically significant increase in PF rate.

The majority of pancreatic fistulae in this study were managed with the drain placed during the initial operation or subsequently by IR. While patients who had DP did not have an overall higher postoperative mortality, 3 of 13 patients who developed PF died during the perioperative period, a 23 % complication-specific mortality. In contrast, PF-associated mortality for primary pancreatic disease is reported to be less than 1 %.12 Due to the high complication-specific mortality in our cohort, we do not recommend DP early in the course of the operation unless meticulous inspection of the peritoneal cavity confirms the feasibility of a complete cytoreduction. In our study, only 37.7 % of DP patients had a complete cytoreduction, further supporting our claim that DP is a surrogate for higher burden of disease.

We attribute the increased mortality of PF to several factors, including the advanced stage of disease, extent of cytoreduction, and altered physical examination resulting from intraoperative chemoperfusion. Importantly, two of the three patients who developed pancreatic fistulae and died also had concurrent enteric leaks. Common findings after HIPEC inclusive of splenectomy, such as abdominal pain, persistent leukocytosis and CT evidence of non-enhancing fluid collections, likely led to late recognition and management of postoperative pancreatic fistulae. With such confounders, we suggest that a left upper quadrant drain should be consistently placed and checked for amylase prior to feeding the patient.

This retrospective, single-institution study is limited by the fact that preoperative assessment of disease involvement and fistula risk factors, including pancreatic texture, and location, were not available for analysis. In addition, the median OS was similar between LGA patients with and without DP because the analyzed cohort included patients with both complete and incomplete cytoreduction. Even though all LGA patients who had a DP associated with complete macroscopic cytoreductions were alive at 12 years, this study is underpowered to conclude if the inclusion of DP to achieve R0/1 cytoreduction improves survival.

CONCLUSIONS

The addition of DP with CRS/HIPEC is associated with a significant increase in perioperative morbidity and PF-specific mortality without significant increase in overall procedural mortality. Therefore, given the increased morbidity, we argue that adding DP should be performed only in cases where a complete cytoreduction is feasible based on the extent and topography of PSD. A multi-institutional analysis is needed to demonstrate if the addition of DP to achieve a complete cytoreduction improves OS of patients with PSD.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Wake Forest University Biostatistics shared resource NCI CCSG P30CA012197.

Footnotes

This work was presented as an oral presentation at the 9th International Symposium on Regional Cancer Therapies, Steamboat Springs, CO, USA, 15–17 February 2014, and the 9th Annual Academic Surgical Congress, San Diego, CA, USA, 4–6 February 2014

DISCLOSURES None.

References

- 1.Chua TC, Moran BJ, Sugarbaker PH, et al. Early- and long-term outcome data of patients with pseudomyxoma peritonei from appendiceal origin treated by a strategy of cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2449–56. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.7166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Elias D, Gilly F, Boutitie F, et al. Peritoneal colorectal carcinomatosis treated with surgery and perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy: retrospective analysis of 523 patients from a multicentric French study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:63–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.9285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Glehen O, Gilly FN, Boutitie F, et al. Toward curative treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis from nonovarian origin by cytoreductive surgery combined with perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy: a multi-institutional study of 1,290 patients. Cancer. 2010;116:5608–18. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shen P, Stewart JH, Levine EA. Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy for peritoneal surface malignancy: overview and rationale. Curr Probl Cancer. 2009;33:125–41. doi: 10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2009.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–13. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bassi C, Dervenis C, Butturini G, et al. Postoperative pancreatic fistula: an international study group (ISGPF) definition. Surgery. 2005;138:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goere D, Malka D, Tzanis D, et al. Is there a possibility of a cure in patients with colorectal peritoneal carcinomatosis amenable to complete cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal chemotherapy? Ann Surg. 2013;257:1065–71. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31827e9289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chi DS, Zivanovic O, Levinson KL, et al. The incidence of major complications after the performance of extensive upper abdominal surgical procedures during primary cytoreduction of advanced ovarian, tubal, and peritoneal carcinomas. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;119:38–42. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eisenhauer EL, Abu-Rustum NR, Sonoda Y, et al. The addition of extensive upper abdominal surgery to achieve optimal cytoreduction improves survival in patients with stages IIIC–IV epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;103:1083–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoffman MS, Tebes SJ, Sayer RA, et al. Extended cytoreduction of intraabdominal metastatic ovarian cancer in the left upper quadrant utilizing en bloc resection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197:209–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.04.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou W, Lv R, Wang X, et al. Stapler vs suture closure of pancreatic remnant after distal pancreatectomy: a meta-analysis. Am J Surg. 2010;200:529–36. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harris LJ, Abdollahi H, Newhook T, Sauter PK, Crawford AG, Chojnacki KA, et al. Optimal technical management of stump closure following distal pancreatectomy: a retrospective review of 215 cases. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14(6):998–1005. doi: 10.1007/s11605-010-1185-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Diener MK, Seiler CM, Rossion I, Kleeff J, Glanemann M, Butturini G, et al. Efficacy of stapler versus hand-sewn closure after distal pancreatectomy (DISPACT): a randomised, controlled multicentre trial. Lancet. 2011;377(9776):1514–22. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60237-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnston FM, Cavataio A, Strasberg SM, Hamilton NA, Simon PO, Trinkaus K, et al. The effect of mesh reinforcement of a stapled transection line on the rate of pancreatic occlusion failure after distal pancreatectomy: review of a single institution’s experience. HPB (Oxford) 2009;11(1):25–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2008.00001.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hamilton NA, Porembka MR, Johnston FM, et al. Mesh reinforcement of pancreatic transection decreases incidence of pancreatic occlusion failure for left pancreatectomy: a single-blinded, randomized controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2012;255:1037–42. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31825659ef. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jin T, Altaf K, Xiong JJ, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies comparing laparoscopic and open distal pancreatectomy. HPB (Oxford) 2012;14:711–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2012.00531.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kleeff J, Diener MK, Z’graggen K, et al. Distal pancreatectomy: risk factors for surgical failure in 302 consecutive cases. Ann Surg. 2007;245:573–82. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000251438.43135.fb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Venkat R, Edil BH, Schulick RD, et al. Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy is associated with significantly less overall morbidity compared to the open technique: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2012;255:1048–1059. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318251ee09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jimenez RE, Hawkins WG. Emerging strategies to prevent the development of pancreatic fistula after distal pancreatectomy. Surgery. 2012;152(3 Suppl 1):S64–70. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2012.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fahy BN, Frey CF, Ho HS, Beckett L, Bold RJ. Morbidity, mortality and technical factors of distal pancreatectomy. Am J Surg. 2002;183(3):237–41. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(02)00790-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]