Abstract

Background

Liver fibrosis is a hallmark of clonorchiasis suffered by millions people in Eastern Asian countries. Recent studies showed that the activation of TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway can potently regulate the hepatic fibrogenesis including Schistosoma spp. and Echinococcus multilocularis-caused liver fibrosis. However, little is known to date about the expression of transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) and other molecules in TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway which may play an important role in hepatic fibrosis caused by C. sinensis.

Methods

A total of 24 mice were individually infected orally with 45 metacercariae, both experimental mice and mocked-infected control mice were anesthetized at 4 week post-infection (wk p.i.), 8 wk p.i. and 16 wk p.i., respectively. For each time-point, the liver and serum from each animal were collected to analyze histological findings and various fibrotic parameters including TGF-β1, TGF-β receptors and down-stream Smads activation, as well as fibrosis markers expression.

Results

The results showed that collagen deposition indicated by hydroxyproline content and Masson’s trichrome staining was increased gradually with the development of infection. The expression of collagen type α1 (Col1a) mRNA transcripts was steadily increased during the whole infection. The mRNA levels of Smad2, Smad3 as well as the protein of Smad3 in the liver of C. sinensis-infected mice were increased after 4 wk p.i. (P < 0.05, compared with normal control) whereas the TGF-β1, TGF-β type I receptor (TGFβRI) and TGF-β type II receptor (TGFβRII) mRNA expression in C. sinensis-infected mice were higher than those of normal control mice after 8 wk p.i. (P < 0.05). However, the gene expression of Smad4 and Smad7 were peaked at 4 wk p.i. (P < 0.05), and thereafter dropped to the basal level at 8 wk p.i., and 16 wk p.i., respectively. The concentrations of TGF-β1 in serum in the C. sinensis-infected mice at 8 wk p.i. and 16 wk p.i (P < 0.05) were significantly higher than those in the control mice.

Conclusions

The results of the present study indicated for the first time that the activation of TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway might contribute to the synthesis of collagen type I which leads to liver fibrosis caused by C. sinensis.

Keywords: Clonorchis sinensis, Liver fibrosis, Transforming growth factor-β, Smads

Background

Clonorchis sinensis is a food-borne zoonotic parasite, which is epidemic in some Eastern Asian countries including China, Korea, Japan, and Vietnam. In humans, it is assumed that approximately 15–20 million people were suffering from clonorchiasis whereas the number of infected people was 12.5 million in China according to a report based on a nationwide survey [1,2]. Human become infected by ingestion of freshwater fish containing C. sinensis metacercariae. The metacercariae develop into C. sinensis juveniles in the duodenum by the stimulation of trypsin, and then rapidly move to the intrahepatic bile duct where the juvenile worms become mature and survive for decades [3,4]. C. sinensis infection can induce significant cholangitis, adenomatous hyperplasia mechanical obstruction of the hepatobiliary duct and cholelithiasis [5]. Furthermore, C. sinensis is considered as a group I carcinogen-metazoan parasite to potentially induce cholangiocarcinoma in humans [6]. Chronic infection with C. sinensis can also potently lead to liver fibrosis which is marked with excessive accumulation of extracellular matrix components (ECM) due to an imbalance between its synthesis and degradation [2,7,8]. Moreover, some components of worms and its excretory/secretory products (ESP) which can probably participate in the development of hepatic fibrosis have been widely investigated in the lab of Professor Yu [9-13]. However, molecular mechanism underlying fibrotic responses of hosts to these virulence factors is not fully elucidated.

Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) as one of major pro-fibrotic cytokines plays a crucial role in orchestrating fibrogenesis and it is demonstrated that active TGF-β1 motivates its downstream signaling pathway, leading to phosphorylation of Smad2 and Smad3 (also called R-Smad) which is meditated by TGF-β type I (TGFβRI) and type II receptors (TGFβRII), phosphorylated Smad2 and Smad3 rapidly combine with a common mediator called Smad4 and subsequently migrates to the nucleus, resulting in massive fibrotic genes expression (such as collagen type I) [14-17]. TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway has been proved as a canonical pathway that can potently regulate the hepatic fibrogenesis [18,19], and a few studies have addressed about the activation of TGF-β/Smad signaling in fibrogenesis caused by parasitic infection, such as Schistosoma spp. and Echinococcus multilocularis, which suggested that TGF-β/Smad signaling play important roles in the development of liver fibrosis [20-22]. However, to our best knowledge, little is known of the expression and potential roles of TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway which may be involved in process of hepatic fibrosis caused by C. sinensis. In the light of this background, the objectives of the present study were to investigate the expression dynamics of TGF-β/Smad pathway and analyze their possible roles in the development of hepatic fibrosis in BALB/c mice infected by C. sinensis.

Methods

Parasites

Pseudorasbora parva, the second intermediate hosts which were naturally infected with C. sinensis, were collected in Guangxi Autonomous Region, People’s Republic of China. And the fish were transported to our laboratory by air. Metacercariae of C. sinensis were collected by digesting fish with a pepsin-HCl (0.6%) artificial gastricjuice. The collected metacercariae were preserved in cold Alsever’s solution with antibiotics until use.

Animals

Female BABL/c mice (6 ~ 8 weeks old, 22 ± 2 g) were purchased from Shanghai Laboratory Animal Co., Ltd (SLAC, Shanghai, China). The mice were housed in an air-conditioned room at 24°C with a 12 h dark/light cycle and permitted free access to standard laboratory food and water. All animal experiments were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Xuzhou Medical Collage. The mice were individually infected orally with 45 metacercariae. Mock-infected control mice were similarly administered with 50 μl of sterile normal solution. Both experimental mice (n = 24) and control mice (n = 15) were divided into 3 groups and anesthetized at 4 week post-infection (wk p.i.), 8 wk p.i. and 16 wk p.i., respectively. For each time-point, the liver and serum from each animal were harvested to analyze histological findings and various fibrotic parameters.

Histological examination and evaluation of hepatic fibrosis in mice caused by C. sinensis

For histological evaluation, all liver samples were fixed in formalin, embedded in paraffin. 4 μm thick sections were prepared and then stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Masson’s trichrome (MT). These specimens were observed and photographed under an inverted microscope. Collagen depositions from 5–8 images of each specimen were quantified using Image-Pro Plus software (Media Cybernetics, Rockville, MD, USA).

Determination of hydroxyproline content

Collagen was also determined by evaluating the concentration of the hydroxyproline (Hyp), an amino acid characteristic of collagen. The lysates were used to measure hydroxyproline contents using commercially available kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Jiancheng Institute of Biotechnology, Nanjing, China). In this kit, hydroxyproline concentration was determined by the reaction of oxidized hydroxyproline with 4-(Dimethylamino) benzaldehyde (DMAB), which was measured spectrophotometrically at 560 nm.

Quantitative real-time PCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted from liver tissues using TRIzol reagent (TIANGEN Biotech, Beijing, China) as described by the manufacturer. RNA was reverse-transcribed using the Reverse Transcription Kit (TIANGEN Biotech, Beijing, China). To investigate the expression of TGF-β/Smad pathway in the liver, relative quantitative RT-PCR (qPCR) was performed using the LightCycler FastStart DNA Master SYBR Green I kit (Roche Applied Science, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturers’ protocol with primer sequences shown in Table 1. The optimal light cycler conditions were: initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min, followed by 40 cycles with denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, annealing at 60°C for 30 s and elongation at 72°C for 30 s (Table 1). Quantification of target gene expression was evaluated in the terms of the comparative cycling threshold (Ct) normalized by β-actin with the 2-△△Ct method.

Table 1.

Primers used in the present study

| Gene | Genbank accession | Primer sequences | Annealing temperature | Expected size (bp) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-SMA | NM_007392.3 | F:5′-AAGAGCATCCGACACTGCTGAC-3′ | 60.0°C | 300 | Present study |

| R:5′-AATAGCCACGCTCAGTCAGG-3′ | |||||

| ColIa | NM_007742.3 | F: 5′-CAGGGTATTGCTGGACAACGTG-3′ | 60.0°C | 107 | Present study |

| R: 5′-GGACCTTGTTTGCCAGGTTCA-3′ | |||||

| Col-III | NM_009930.2 | F: 5′-TGGCACAGCAGTCCAACGTA-3′ | 60.0°C | 122 | Present study |

| R: 5′-AAGGACAGATCCTGAGTCACAGACA-3′ | |||||

| TGF-β1 | NM_011577 | F: 5′-GTGTGGAGCAACATGTGGAACTCTA-3′ | 60.0°C | 143 | 20 |

| R: 5′-TTGGTTCAGCCACTGCCGTA-3′ | |||||

| TGFβRI | NM_009370.2 | F: 5′-TGCAATCAGGACCACTGCAATAA-3′ | 60.0°C | 133 | 20 |

| R: 5′-GTGCAATGCAGACGAAGCAGA-3′ | |||||

| TGFβRII | NM_009371.2 | F: 5′-AAATTCCCAGCTTCTGGCTCAAC-3′ | 60.0°C | 100 | 20 |

| R: 5′-TGTGCTGTGAGACGGGCTTC-3′ | |||||

| Smad2 | NM_010754 | F: 5′-TGCATTCTGGTGTTCAATCG-3′ | 60.0°C | 198 | 20 |

| R: 5′-CGAGTTTGATGGGTCTGTGA-3′ | |||||

| Smad3 | NM_016769 | F: 5′-GTCAACAAGTGGTGGCGTGTG-3′ | 60.0°C | 150 | 20 |

| R: 5′-GCAGCAAAGGCTTCTGGGATAA-3′ | |||||

| Smad4 | NM_008540 | F: 5′-TGACGCCCTAACCATTTCCAG-3′ | 60.0°C | 136 | 20 |

| R: 5′-CTGCTAAGAGCAAGGCAGCAAA-3′ | |||||

| Smad7 | NM_001042660.1 | F: 5′-AGAGGCTGTGTTGCTGTGAATC-3′ | 60.0°C | 126 | 20 |

| R: 5′-CCATTGGGTATCTGGAGTAAGGA-3′ | |||||

| β-actin | NM_007393.3 | F: 5′-CGTGGGCCGCCCTAGGCACCA-3′ | 60.0°C | 243 | Present study |

| R: 5′-TTGGCCTTAGGGTTCAGGGGGG-3′ |

Western blot

Total protein was extracted from liver tissues and analyzed with bicinchoninic acid protein concentration assay kit (Beyotime Biotech, Beijing, China). Sample protein was separated by electrophoresis in 12% SDS-PAGE with a Bio-Rad electrophoresis system (Hercules, CA, USA). The primary antibodies (rabbit anti-Smad3 antibody, UCallM biotech Co., Ltd, Wuxi, China, 1:1000 dilutions) were incubated at 4°Covernight. The corresponding horseradish-peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (anti-rabbit IgG, 1:5000 dilutions) were incubated for 1 h at room temperature. The membrane containing antibody-protein complexes were visualized with an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system on radiograph film. The brands were scanned and analyzed by the software Quantity ONE (Bio-rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The expression of protein in each sample was normalized by α-Tublin(Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA, USA).

Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Serum from each mouse was immediately used to evaluate the concentration of TGF-β1 by a specific ELISA kit (eBiosciences, CA, USA). In brief, samples were firstly activated by 1 mol/L HCl, and then samples as well as serial dilutions of standards were added to 96-well plates pre-coated with anti-TGF-β1 and pre-blocked with PBS containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), after samples were washed, horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated streptavidin A in PBS containing 10% FBS was added for 30 min at room temperature. After final washes, the HRP substrate TMB (3,3,5,5-tetramethylbenzidine) was added, and the optical density of the color reaction was measured at 450 nm. Concentrations of cytokine in the sera were calculated using standard curves as references.

Data analysis

All values were expressed as mean ± SEM. Comparisons between control and each experimental group were made by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Student’s unpaired t-test using the SPSS 13.0 statistical package. Differences were considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

Results

Histological findings and evaluation of hepatic fibrosis in mice caused by C. sinensis

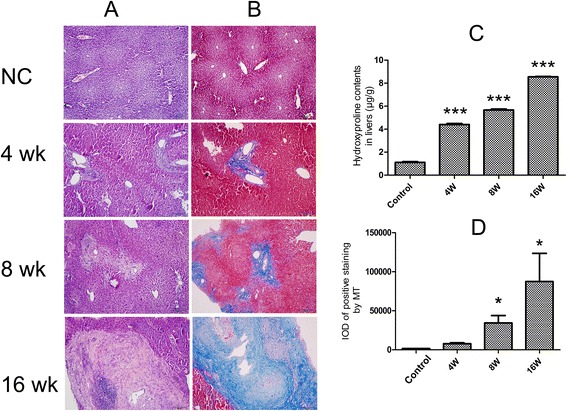

In the normal control group, the hepatocyte arranged tightly and hepatic lobules were observed completely. In contrast, in the C. sinensis-infected group, fibrotic cords were observed in the periportal areas of C. sinensis- infected mice at 4 wk p.i. and 8 wk p.i., and as the infection developed, collagen fibers were extended from portal areas to liver lobule of mice at 16 wk p.i., the arrangement of hepatocyte was disordered and pseudolobules were observed in some serious cases at this time point (Figure 1A and Figure 1B). The quantities of collagen depositions were increased gradually with the development of infection, and statistical difference and significant difference were observed at 8 wk p.i. (P < 0.05), and 16 wk p.i. (P < 0.05), respectively, compared with normal control mice (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Evaluation of hepatic fibrosis in mice caused by Clonorchis sinensis at 4 week post-infection (wk p.i.), 8 wk p.i. and 16 wk p.i. (A) Histological examination of liver tissues from C. sinensis-infected mice and normal control mice at different time-points as indicated. (B) Collagen depositions were specifically stained by Masson’s trichrome at different time-points as indicated. (C) Hydroxyproline (Hyp) concentration was measured in liver homogenate (0.1 g) in fibrotic or normal livers of BALB/c mice at indicated time-points. (D) Collagen depositions from each specimen were semi-quantified using Image-Pro Plus software. Data were presented as mean ± SEM from 8 C. sinensis-infected mice and 5 normal control (NC) mice at each time-point, * = P < 0.05, ** = P < 0.01, *** = P < 0.001 versus control mice.

The hydroxyproline which is a major component of collagen was also evaluated as an indicator of collagen content. Compared with normal control mice, the levels of hydroxyproline were significantly augmented at 4 wk p.i. (P < 0.001), and thereafter dramatically increased at 8 wk p.i. (P < 0.001) and 16 wk p.i. (P < 0.001, Figure 1C).

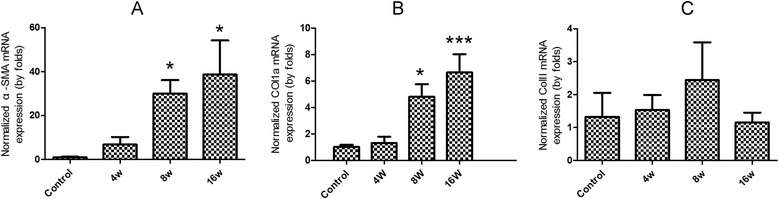

The expression of the pro-fibrotic molecular markers in livers of mice during C. sinensis infection

qPCR results showed that the mRNA level of alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) was dramatically increased from 4 wk p.i. to 16 wk p.i., and there were statistical differences for α-SMA mRNA expression between 8 wk p.i. or 16 wk p.i. and control animals (P < 0.05, Figure 2A). The results also showed that mRNA levels of collagen α1(Col1a) expression were steadily increased from 4 wk p.i. to 16 wk p.i., and significant differences were found at 8 wk p.i. (P < 0.05) and 16 wk p.i. (P < 0.05), compared with normal control animals (Figure 2B). However, collagen type III (Col III) expression was not changed at 4 wk p.i., 8 wk p.i. or 16 wk p.i., and there were no statistical differences between C. sinensis-infected animals and normal control ones (Figure 2C, P > 0.05).

Figure 2.

The mRNA expression of the pro-fibrotic molecular markers in livers of mice during Clonorchis sinensis infection. Mice were orally infected with 45 metacercariae of C. sinensis, livers were collected from infected and non-infected mice at indicated time-points and mRNA levels were determined by qPCR (normalized to beta-actin transcript levels). (A) α-SMA; (B) Col1a; (C) Col III. Data were presented as mean ± SEM from 8 C. sinensis-infected mice and 5 normal control mice at each time-point, * = P < 0.05, ** = P < 0.01, *** = P < 0.001 versus control mice.

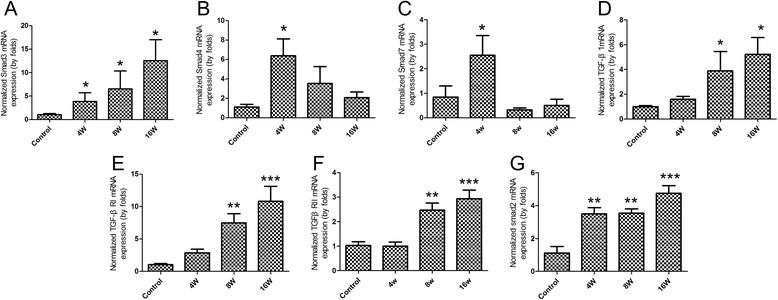

The mRNA expression of TGF-β/Smad in the liver of BALB/c during C. sinensis-infection

As shown in Figure 3, mRNA expression of TGF-β1, TGFβRI, TGFβRII, Smad2 and Smad3 were upregulated in the liver of C. sinensis-infected mice, compared with normal control mice. And significant differences were observed from 8 wk p.i. to 16 wk p.i. for TGF-β1, TGFβRI, TGFβRII (P < 0.05), whereas the mRNA expression levels of Smad2 and Smad3 showed statistical differences from 4 wk p.i. to 16 wk p.i. compared with normal control mice (P < 0.05). However, Smad4 and Smad7 mRNA peaked at 4 wk p.i., thereafter decreased at 8 wk p.i. and 16 wk p.i. and there was a significant difference between C. sinensis-infected mice and control group at 4 wk p.i. (P < 0.05).

Figure 3.

Gene expression of TGF-β/Smad signaling in the liver fibrosis caused by C. sinensis . Mice were orally infected with 45 metacercariae of C. sinensis, livers were collected from infected and non-infected mice at indicated time-points and mRNA levels were determined by qPCR (normalized to beta-actin transcript levels). (A) Smad3; (B) Smad4; (C) Smad7; (D) TGF-β1; (E) TGFβRI; (F) TGFβRII; (G) Smad2. Data were presented as mean ± SEM from 8 C. sinensis-infected mice and 5 normal control mice at each time-point, * = P < 0.05, ** = P < 0.01, *** = P < 0.001 versus control mice.

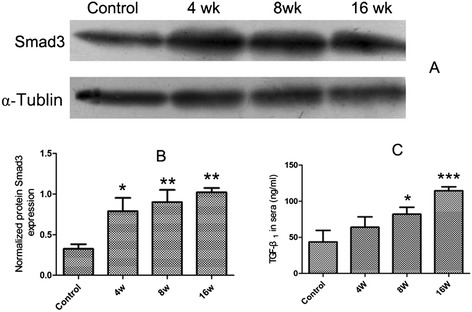

The protein expression of Smad3 in livers of C. sinensis-infected mice and dynamic changes of serous TGF-β1 in mice infected by C. sinensis

The Smad3 protein in the liver of C. sinensis-infected mice was increased dramatically as the infection developed, which was consistent with the mRNA expression of Smad3. Statistical differences were found in expression of Smad3 in all C. sinensis-infected groups, compared with normal control group (Figure 4A and Figure 4B, P < 0.05).

Figure 4.

The protein expression of Smad3 in livers and dynamic changes of serous TGF-β 1 in sera from C. sinensis -infected and non-infected mice . Mice were orally infected with 45 metacercariae of C. sinensis, livers and sera were collected from infected and non-infected mice at indicated time-points and the protein expression levels of Smad3 (A&B) in the livers and TGF-β1 (C) in the sera from mice were determined by western-blot and ELISA, respectively. Data were presented as mean ± SEM from 8 C. sinensis-infected mice and 5 normal control mice at each time-point, * = P < 0.05, ** = P < 0.01, *** = P < 0.001 versus control mice.

As shown in Figure 4C, during the whole experimental infection, the concentration of TGF-β1 in the serum at 8 wk p.i. and 16 wk p.i. was significantly higher than that of in the control mice (P < 0.05), and the level of TGF-β1 were increased from 4 wk p.i. to 16 wk p.i during the development of infection.

Discussion

Previous studies showed that liver fibrosis was orchestrated by a complex network of signaling pathways involved in regulation the deposition of extracellular matrix, and of these signaling pathways, TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway is considered as the most prominent mediator in accelerating liver fibrosis [18,23]. Beside TGF-β, IL-13 and Il-17 were recently demonstrated as another critical pro-fibrotic cytokines in liver fibrosis, for example, IL-13 can potently induce the synthesis of collagen I and other fibrotic markers directly in Schistosoma spp. caused liver fibrosis whereas IL-17A can promote the activation of HSC and drive the mRNA expression of the IL-6, α-SMA, collagen, as well as TGF-β1 in carbon tetrachloride–induced liver fibrosis [24-27]. However, little is known of the molecular mechanism underlying C. sinensis caused liver fibrosis. In the present study, we used BALB/c mice to explore the possible mechanism underlying the liver fibrosis caused by C. sinensis. Similar with other study, we showed that BALB/c mice can develop a moderate periductal fibrosis at 4 wk p.i. and massive deposition of extracellular matrix after 8 wk p.i. demonstrated by HE and MT staining, suggesting that the mouse model for C. sinensis induced-liver fibrosis in the present study was established successfully [7,8].

Biological functions of TGF-β and its roles in regulating ECM deposition have been intensively reviewed, and proteins of the Smads family members are important mediators that transduce signals induced by TGF-β to specific target genes in the nucleus, leading to the expression of pro-fibrotic genes [28,29]. There were also some studies suggesting that TGF-β1 and its downstream Smads played a central role in parasite-induced liver fibrosis [20,30,31], for example, in Schistosoma mansoni-infected mouse, the increased expression of TGF-β1 and its receptors led to extensive accumulation of extracellular matrix proteins and treatment with anti-fibrotic drugs like praziquantel can reduce the concentration of TGF-β signicantly and led to an reversible liver fibrosis in S. mansoni-infected mice [32,33].

As expected, hepatic mRNA transcriptions of fibrotic markers such as collagen type I (Col1a), TGF-β1, α-SMA and hydroxyproline contents were increased with the degree of C. sinensis-caused hepatic fibrosis, which was indicated by MT staining. To further investigate whether TGF-β/Smad signaling was activated during C. sinensis-caused liver fibrosis or not, the expression of genes and proteins within TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway was examined. In the present study, the mRNA expression of TGF-β1, Smad2/3, TGFβRI and TGFβRII was significantly stronger in the livers of C. sinensis infected-mice than that in control ones, and these changes were positively correlated with the degrees of hepatic fibrosis (data is not shown), suggesting that TGFβ/Smad signaling pathway may be involved in the development of liver fibrosis due to C. sinensis infection. However, our study showed Smad4 was found increased at 4 wk p.i., and its expression decreased with the development of hepatic fibrosis, which suggested that the effects of Smad4 might occur at early and middle stage of hepatic fibrosis [34]. Our results also showed that Smad7 expression heightened only at the 4 wk p.i. and the expression of Smad2 was significantly higher in the livers of C. sinensis-infection mice, indicating that Smad7 played a negative role in fine-tuning of TGF-β signals since the increased Smad2 may suppress the expression of Smad7 conversely [35,36].

Conclusions

In conclusion, our results of the present study suggested, for the first time, that expression dynamics of TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway may be involved in the development of hepatic fibrosis caused by C. sinensis. The further studies should be warranted to elucidate detailed roles of TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway in C. sinensis caused liver fibrosis, which may provide basic information for control clonorchiasis.

Acknowledgments

Project support was provided, in part, the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 81171590 and 31302077), the Open Funds of the State Key Laboratory of Veterinary Etiological Biology, Lanzhou Veterinary Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences (Grant No. SKLVEB2013KFKT005), the Graduate Innovation Program in Science and Technology of Jiangsu Province, China (Grant No. KYLX14-1448). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Chao Yan and Lin Wang contributed equally to this work.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: KYZ, RXT, and CY. Performed the experiments: CY and LW; Analyzed the data: LW and CY; Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: BZ, BL, BBZ, YHW, JXC and XYL; Wrote the paper: CY. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Chao Yan, Email: yanchao6957@163.com.

Lin Wang, Email: linhuaisu@sina.com.

Bo Li, Email: 413923975@qq.com.

Bei-Bei Zhang, Email: 1097526129@qq.com.

Bo Zhang, Email: 1262179198@qq.com.

Yan-Hong Wang, Email: 316987724@qq.com.

Xiang-Yang Li, Email: lxy20032008@163.com.

Jia-Xu Chen, Email: chenjiaxu1962@163.com.

Ren-Xian Tang, Email: Tangrenxian-t@163.com.

Kui-Yang Zheng, Email: ZKY02@163.com.

References

- 1.Fang YY, Chen YD, Li XM, Wu J, Zhang QM, Ruan CW. Current prevalence of Clonorchis sinensis infection in endemic areas of China. ZhongguoJi Sheng Chong Xue Yu Ji Sheng Chong Bing Za Zhi 2008, 26:99–103, 109. [PubMed]

- 2.Hong ST, Fang Y. Clonorchis sinensis and clonorchiasis, an update. Parasitol Int. 2012;61:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li S, Chung YB, Chung BS, Choi MH, Yu JR, Hong ST. The involvement of the cysteine proteases of Clonorchis sinensis metacercariae in excystment. Parasitol Res. 2004;93:36–40. doi: 10.1007/s00436-004-1097-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim TI, Yoo WG, Kwak BK, Seok JW, Hong SJ. Tracing of the Bile-chemotactic migration of juvenile Clonorchis sinensis in rabbits by PET-CT. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5:e1414. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen J, Xu MJ, Zhou DH, Song HQ, Wang CR, Zhu XQ. Canine and feline parasitic zoonoses in China. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5:152. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-5-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bouvard V, Baan R, Straif K, Grosse Y, Secretan B, El Ghissassi F, et al. A review of human carcinogens–Part B: biological agents. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:321–2. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70096-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoon BI, Choi YK, Kim DY, Hyun BH, Joo KH, Rim HJ, et al. Infectivity and pathological changes in murine clonorchiasis: comparison in immunocompetent and immunodeficient mice. J Vet Med Sci. 2001;63:421–5. doi: 10.1292/jvms.63.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi YK, Yoon BI, Won YS, Lee CH, Hyun BH, Kim HC, et al. Cytokine responses in mice infected with Clonorchis sinensis. Parasitol Res. 2003;91:87–93. doi: 10.1007/s00436-003-0934-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang X, Hu F, Hu X, Chen W, Huang Y, Yu X. Proteomic identification of potential Clonorchis sinensis excretory/secretory products capable of binding and activating human hepatic stellate cells. Parasitol Res. 2014;113:3063–71. doi: 10.1007/s00436-014-3972-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liang P, Sun J, Huang Y, Zhang F, Zhou J, Hu Y, et al. Biochemical characterization and functional analysis of fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase from Clonorchis sinensis. Mol Biol Rep. 2013;40:4371–82. doi: 10.1007/s11033-013-2508-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang F, Liang P, Chen W, Wang X, Hu Y, Liang C, et al. Stage-specific expression, immunolocalization of Clonorchissinensis lysophospholipase and its potential role in hepatic fibrosis. Parasitol Res. 2013;112:737–49. doi: 10.1007/s00436-012-3194-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zheng M, Hu K, Liu W, Hu X, Hu F, Huang L, et al. Proteomic analysis of excretory secretory products from Clonorchis sinensis adult worms: molecular characterization and serological reactivity of a excretory-secretory antigen-fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase. Parasitol Res. 2011;109:737–44. doi: 10.1007/s00436-011-2316-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu F, Hu X, Ma C, Zhao J, Xu J, Yu X. Molecular characterization of a novel Clonorchis sinensis secretory phospholipase A(2) and investigation of its potential contribution to hepatic fibrosis. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2009;167:127–34. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kanzler S, Lohse AW, Keil A, Henninger J, Dienes HP, Schirmacher P, et al. TGF-beta1 in liver fibrosis: an inducible transgenic mouse model to study liver fibrogenesis. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:1059–68. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.276.4.G1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dooley S, Delvoux B, Streckert M, Bonzel L, Stopa M, ten Dijke P, et al. Transforming growth factor beta signal transduction in hepatic stellate cells via Smad2/3 phosphorylation, a pathway that is abrogated during in vitro progression to myofibroblasts. TGFbeta signal transduction during transdifferentiation of hepatic stellate cells. FEBS Lett. 2001;502:4–10. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(01)02656-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schiller M, Javelaud D, Mauviel A. TGF-beta-induced SMAD signaling and gene regulation: consequences for extracellular matrix remodeling and wound healing. J Dermatol Sci. 2004;35:83–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2003.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yoshida K, Murata M, Yamaguchi T, Matsuzaki K. TGF-β/Smad signaling during hepatic fibro-carcinogenesis (review) Int J Oncol. 2014;45:1363–71. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2014.2552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Date M, Matsuzaki K, Matsushita M, Sakitani K, Shibano K, Okajima A, et al. Differential expression of transforming growth factor-beta and its receptors in hepatocytes and nonparenchymal cells of rat liver after CCl4 administration. J Hepatol. 1998;28:572–81. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(98)80280-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yoshida K, Matsuzaki K. Differential regulation of TGF-β/Smad signaling in hepatic stellate cells between acute and chronic liver injuries. Front Physiol. 2012;3:53. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang J, Zhang C, Wei X, Blagosklonov O, Lv G, Lu X, et al. TGF-β and TGF-β/Smad signaling in the interactions between Echinococcus multilocularis and its hosts. PLoS One. 2013;8:e55379. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang BB, Cai WM, Tao J, Zheng M, Liu RH. Expression of Smad proteins in the process of liver fibrosis in mice infected with Schistosoma japonicum. Zhong guo Ji Sheng Chong Xue Yu Ji Sheng Chong Bing Za Zhi. 2013;31:89–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen BL, Peng J, Li QF, Yang M, Wang Y, Chen W. Exogenous bone morphogenetic protein-7 reduces hepatic fibrosis in Schistosomajaponicum-infected mice via transforming growth factor-β/Smad signaling. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:1405–15. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i9.1405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bataller R, Brenner DA. Liver fibrosis. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:209–18. doi: 10.1172/JCI24282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu Y, Munker S, Müllenbach R, Weng HL. IL-13 signaling in liver fibrogenesis. Front Immunol. 2012;3:116. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chuah C, Jones MK, Burke ML, McManus DP, Gobert GN. Cellular and chemokine-mediated regulation in schistosome-induced hepatic pathology. Trends Parasitol. 2014;30:141–50. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2013.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tang J, Huang H, Ji X, Zhu X, Li Y, She M, et al. Involvement of IL-13 and tissue transglutaminase in liver granuloma and fibrosis after schistosoma japonicum infection. Mediators Inflamm. 2014;2014:753483. doi: 10.1155/2014/753483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tan Z, Qian X, Jiang R, Liu Q, Wang Y, Chen C, et al. IL-17A plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of liver fibrosis through hepatic stellate cell activation. J Immunol. 2013;191:1835–44. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen N, Geng Q, Zheng J, He S, Huo X, Sun X. Suppression of the TGF-β/Smad signaling pathway and inhibition of hepatic stellate cell proliferation play a role in the hepatoprotective effects of curcumin against alcohol-induced hepatic fibrosis. Int J Mol Med. 2014;34:1110–6. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2014.1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dooley S, ten Dijke P. TGF-β in progression of liver disease. Cell Tissue Res. 2012;347:245–56. doi: 10.1007/s00441-011-1246-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhu D, He X, Duan Y, Chen J, Wang J, Sun X, et al. Expression of microRNA-454 in TGF-β1-stimulated hepatic stellate cells and in mouse livers infected with Schistosoma japonicum. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:148. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.El-Lakkany NM, Hammam OA, El-Maadawy WH, Badawy AA, Ain-Shoka AA, Ebeid FA. Anti-inflammatory/anti-fibrotic effects of the hepatoprotectivesilymarin and the schistosomicide praziquantel against Schistosoma mansoni-induced liver fibrosis. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5:9. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-5-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barros AF, Oliveira SA, Carvalho CL, Silva FL, de Souza VC, da Silva AL, et al. Low transformation growth factor-β1 production and collagen synthesis correlate with the lack of hepatic periportal fibrosis development in undernourished mice infected with Schistosoma mansoni. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2014;109:210–9. doi: 10.1590/0074-0276140266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Attia YM, Elalkamy EF, Hammam OA, Mahmoud SS, El-Khatib AS. Telmisartan, an AT1 receptor blocker and a PPAR gamma activator, alleviates liver fibrosis induced experimentally by Schistosoma mansoni infection. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:199. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-6-199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang HQ, Ding XD, Wu Q, Zhang Q, Huang Y, Yang F. Expression of transforming growth factor–beta and Smads in hepatic fibrosis induced by Schistosoma Japonica in mice. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;16:929–34. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sobral LM, Montan PF, Zecchin KG, Martelli-Junior H, Vargas PA, Graner E, et al. Smad7 blocks transforming growth factor-β1-induced gingival fibroblast-myofibroblast transition via inhibitory regulation of Smad2 and connective tissue growth factor. J Periodontol. 2011;82:642–51. doi: 10.1902/jop.2010.100510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kamiya Y, Miyazono K, Miyazawa K. Smad7 inhibits transforming growth factor-beta family type i receptors through two distinct modes of interaction. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:30804–13. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.166140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]