Abstract

UCP3's exact physiological function in lipid handling in skeletal and cardiac muscle remains unknown. Interestingly, etomoxir, a fat oxidation inhibitor and strong inducer of UCP3, is proposed for treating both diabetes and heart failure. We hypothesize that the upregulation of UCP3 upon etomoxir serves to protect mitochondria against lipotoxicity. To evaluate UCP3's role in skeletal muscle (skm) and heart under lipid-challenged conditions, the effect of UCP3 ablation was examined in a state of dysbalance between fat availability and oxidative capacity. Wild type (WT) and UCP3−/− mice were subjected to high-fat feeding for 14 days. From day 6 onwards, they were given either saline or etomoxir. Etomoxir treatment induced an increase in markers of lipotoxicity in skm compared to saline. This increase upon etomoxir was similar for both, WT and UCP3−/− mice, suggesting that UCP3 does not play a role in protection against lipotoxicity. Interestingly, we observed 25 % mortality in UCP3−/−s upon etomoxir administration vs. 11 % in WTs. This increased mortality in UCP3−/− compared to WT mice could not be explained by differences in cardiac lipotoxicity, apoptosis, fibrosis (histology, immunohisto-chemistry), oxidative capacity (respirometry) or function (echocardiography). Electrophysiology demonstrated, however, prolonged QRS and QTc intervals and greater susceptibility to ventricular tachycardia upon programmed electrical stimulation in etomoxir-treated UCP3−/−s versus WTs. Isoproterenol administration after pacing resulted in 75 % mortality in UCP3−/−s vs. 14 % in WTs. Our results argue against a protective role for UCP3 on skm metabolism under lipid overload, but suggest UCP3 to be crucial in prevention of arrhythmias upon lipid-challenged conditions.

Keywords: Arrhythmia, Metabolism, Mitochondria, Muscle, Uncoupling protein

Introduction

The inner mitochondrial membrane uncoupling proteins (UCPs) are suggested to regulate the proton gradient over the inner mitochondrial membrane, thereby regulating mitochondrial ATP production and/or mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production [4, 9]. Despite its homology to the well-characterized brown adipose tissue-specific UCP1, the exact mechanism and physiological function for the skeletal and cardiac muscle variant UCP3 have not been revealed. UCP3 has been closely tied to fatty acid metabolism, as UCP3 expression is downregulated when fatty acid oxidation is improved, such as following endurance training [33, 38] or (pharmacologically induced) weight reduction [19]. Conversely, UCP3 levels are upregulated when the fatty acid supply exceeds oxidation, e.g., upon a high-fat (HF) diet [46], lipid infusion [11], fasting [18], or upon pharmacological inhibition of fat oxidation by etomoxir [35, 36].

UCP3 is mainly expressed in skeletal and cardiac muscle. It has been shown that UCP3 is reduced by 50 % in skeletal muscle (skm) of obese type 2 diabetes patients [13, 34], who often exhibit mitochondrial dysfunction, lipotoxicity and elevated oxidative stress [4, 5]. In contrast, UCP3 expression is markedly increased in cardiac tissue of human heart failure patients [21]. Using transgenic animal models, it was recently shown that UCP3 might affect cardiac energy efficiency under high-fat conditions [2], suggesting that elevated UCP3 levels result in energy deficiency that is characteristic for heart failure. However, the potential role of UCP3 in skeletal and cardiac muscle is still under debate.

One of the strongest inductions of UCP3 can be achieved by the pharmacological inhibition of fat oxidation with etomoxir, both in humans and rodents [35, 36]. This compound is able to reduce the mitochondrial entry of long chain fatty acids via irreversible inhibition of carnitine palmitoyl transferase-1 (CPT1), thereby inhibiting mitochondrial lipid oxidation and forcing increased glucose oxidation [15]. Etomoxir, or CPT1 inhibition, in general, has been proposed as a therapeutic target for the treatment of heart failure [16, 42], since a shift towards glucose oxidation may improve cardiac energy efficiency [15]. In addition, inhibiting fatty acid oxidation to force glucose oxidation has been suggested to improve skm insulin resistance [16, 40]. We have previously hypothesized that the strong induction of UCP3 upon the inhibition of fat oxidation serves to prevent lipotoxicity, however, experimental data so far are lacking.

To clarify the role of UCP3 during lipid-challenged conditions, we investigated the effect of etomoxir administration on skeletal and cardiac muscle energy and lipid metabolism in UCP3 knockout mice (UCP3−/−) and wild type (WT) littermates. Our data suggest that there was no significant role for skm UCP3 in protection against lipid-induced mitochondrial dysfunction. However, cardiac UCP3 was crucial to maintain cardiac function under these lipid-challenged conditions, and absence of UCP3 under these conditions markedly enhanced the risk of sudden cardiac death.

Materials and methods

Animals

Male UCP3−/− and WT C57Bl/6 control mice (n = 7–8 per group, unless otherwise stated, age 14–15 weeks) received a 45 % HF diet for a period of 14 days. At day 6 of the dietary intervention, both mice strains were randomly divided into two groups: (1) etomoxir, or (2) saline. During the remaining 8 days of the dietary intervention, animals received a daily dose of either etomoxir (experimental groups; 20 mg/kg body weight, dissolved in 0.9 % NaCl (w/v), as previously used by Luiken et al. [17]) or saline (control groups; 0.9 % NaCl) via intraperitoneal (i.p.) injections. The last injection was administered 24 h before sacrificing the animals. All experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Maastricht University and Baylor College of Medicine and complied with the principles of laboratory animal care. A detailed description of all procedures can be found in the Online Data Supplement.

Results

Lack of UCP3 in relation to skeletal muscle lipotoxicity

To determine the effect of UCP3 ablation on skm lipotoxicity WT and UCP3−/− mice were fed a HF diet for 14 days, and exposed to either saline or etomoxir for 8 days starting at day 6 of the dietary intervention. Body weight (~27 g) was similar between animal groups, both at the start and at the end of the saline or etomoxir treatment (Table 1 supplemental).

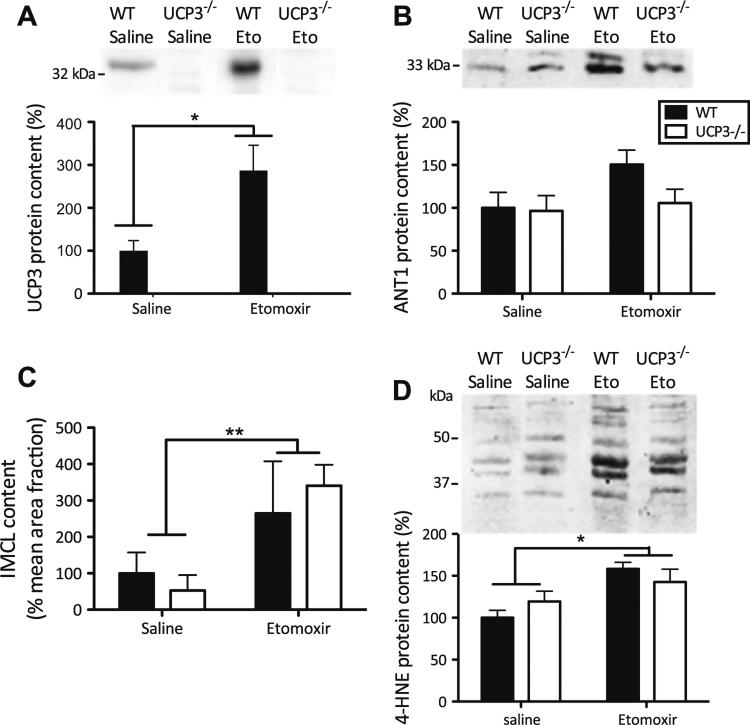

UCP3 protein was not detected in skm of UCP3−/− mice, regardless of the etomoxir intervention (Fig. 1a), confirming their genotype. Additionally, UCP2 protein levels were measured and appeared to be similar in all experimental groups, thus no compensatory upregulation of UCP2 protein expression was found (genotype effect: P = 0.443; etomoxir effect: P = 0.622; genotype 9 etomoxir effect: P = 0.669) (Figure 1 supplemental). In WT mice, etomoxir treatment resulted in a ~threefold increase in skm UCP3 protein levels (Fig. 1a, P = 0.01). No differences were detected in the protein levels of any of the complexes of the electron transport chain among the groups studied (Table 2 supplemental), implying similar mitochondrial densities in skm of these animals. Also no changes were found in the protein content of the adenine nucleotide transporter (ANT), which has been suggested to be involved in mitochondrial uncoupling (Fig. 1b). A trend towards increased ANT levels in WT mice upon etomoxir compared with saline was observed, but this did not reach statistical significance (P = 0.07).

Fig. 1.

Lack of UCP3 does not lead to skeletal muscle lipotoxicity. Western blots and Oil red O stainings were performed in tibialis anterior muscle of WT and UCP3−/− mice. a UCP3 protein expression levels in mice. The etomoxir intervention resulted in an increased UCP3 protein content in WT mice. b No effects of etomoxir or lack of UCP3 were found on ANT1 protein levels. c In both, WT and UCP3−/− mice, etomoxir significantly elevated intramyocellular lipids (IMCL) content. Values are percentage positive Oil Red O-stained area per mean cell surface area. d Elevated levels of 4-HNE protein adducts upon etomoxir treatment. The mean amounts of protein levels and IMCL content in WT saline-treated mice were set to 100 %. (n = 5–8 per group) Values are expressed as mean ± SE. *P < 0.05, **P = 0.01 by 2-way Anova analyses

Etomoxir inhibits the transport of lipids into mitochondria, and hence the mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation. Increased amounts of intramyocellular lipid (IMCL), e.g., when lipid supply exceeds oxidation, are associated with upregulated UCP3 levels. Therefore, we measured IMCL content. Etomoxir treatment resulted in ~fourfold higher lipid accumulation within the tibialis anterior muscle (Fig. 1c, P < 0.01), but no effect due to lack of UCP3, or genotype × intervention interaction was found. These data imply that UCP3 does not influence IMCL accumulation under lipid-challenged conditions. Additionally, no effect was found on levels of DAG (genotype effect: P = 0.172; etomoxir effect: P = 0.748; genotype × etomoxir effect: P = 0.650) or cholesterol (genotype effect: P = 0.371; etomoxir effect: P = 0.736; genotype × etomoxir effect: P = 0.586) levels in quadriceps muscle, whereas MAG levels were undetectable (Figure 2 supplemental).

To determine whether UCP3 could lower oxidative stress in skm, we measured 4-HNE lipid peroxidation products (Fig. 1d). Quantification of lipid peroxidation product levels revealed increased oxidative damage upon etomoxir treatment (P < 0.01), but no genotype or geno-type × intervention interaction effects were found (Fig. 1d), implying that UCP3 does not lower oxidative damage under lipid-challenged conditions.

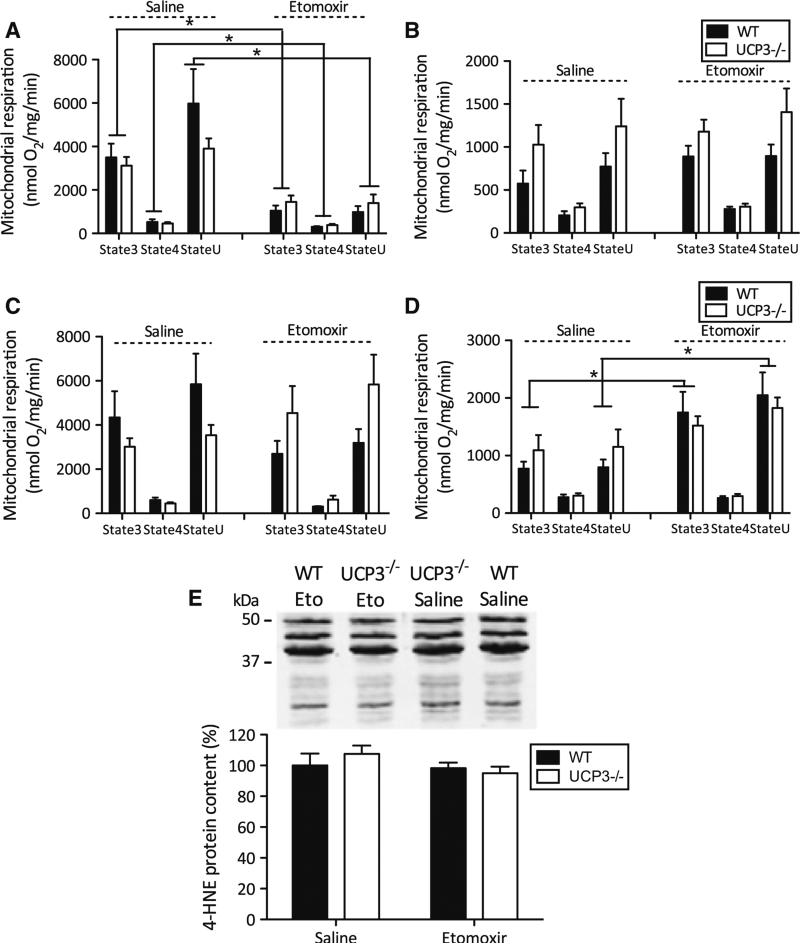

Skeletal muscle mitochondrial oxidative capacity

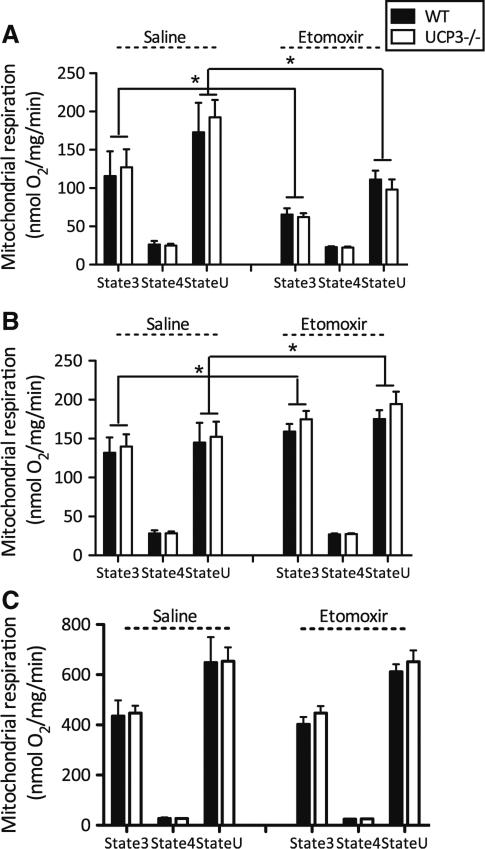

Next, we measured mitochondrial respiration in isolated skm mitochondria. Consistent with an inhibitory effect of etomoxir on CPT1, the etomoxir intervention resulted in a 53 % lower ADP-driven (state 3) respiration (P < 0.01) and 57 % lower uncoupled respiration (state U) (P < 0.01), upon palmitoyl-CoA + carnitine, without a genotype effect (Fig. 2a). Interestingly, when using palmitoyl-carnitine as a fatty acid substrate, without requirement of CPT1, etomoxir resulted in a 23 % higher ADP-driven respiration (P < 0.05) and a tendency towards higher uncoupled respiration (P = 0.06), but this effect was not different between genotypes (Fig. 2b). With none of the fatty acid substrates, an effect of etomoxir, genotype or genotype × etomoxir interaction on leak (state 4o) respiration upon addition of oligomycin (which inhibits ATP synthesis) was detected. ADP-driven respiration in isolated mitochondria, using pyruvate as a glycolytic-derived substrate, was not affected by etomoxir or genotype and no interaction effect was observed (Fig. 2c). Also, etomoxir did not alter leak respiration upon pyruvate as a substrate or uncoupled respiration after addition of the chemical uncoupler FCCP.

Fig. 2.

Etomoxir inhibited CPT1-dependent mitochondrial respiration upon fatty acid substrates. UCP3 ablation does not affect skeletal muscle mitochondrial oxidative capacity. State 3, state 4o and state U (uncoupled) mitochondrial respiration were monitored in UCP3−/− and WT mice treated with etomoxir or saline. Palmitoyl CoA + carnitine (a) palmitoyl-carnitine (b) and pyruvate (c) were used as substrates. Mitochondrial protein concentrations were 0.1 mg protein/ml for pyruvate and 0.25 mg protein/ml for palmitoyl CoA + carnitine and palmitoyl-carnitine. Values are expressed in nmol/mg mitochondrial protein/min. (n = 7–8 per group) Values are expressed as mean ± SE. *P < 0.05 by 2-way Anova analyses

In line with the respiration data obtained from isolated mitochondria, there were no genotype effects on the maximal activities of β-HAD and PFK in skm homogenates, indicating similar skm β-oxidative and glycolytic capacities in WT and UCP3−/− mice (Figure 3 supplemental).

Taken together, our data do not support a role for UCP3 in the preservation of skm mitochondrial function under lipid-challenged conditions

Sudden cardiac arrest in UCP3−/− mice upon lipid challenge

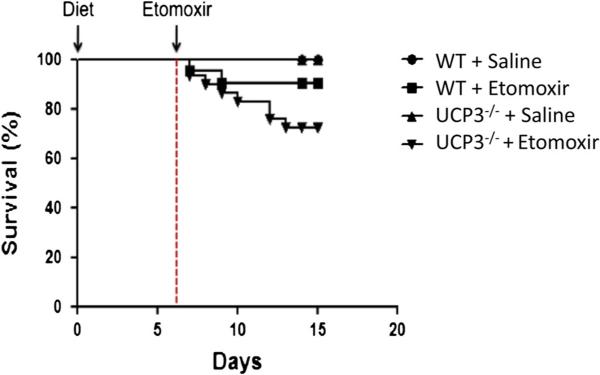

Interestingly, during our initial experiments focused on skm metabolism, we observed that 6 out of 24 UCP3−/− mice died during the first days of etomoxir, an effect that we did not observe in WT mice (Fig. 3). Therefore, we expanded the number of animals to further investigate underlying mechanisms in the heart. We investigated if intracardiomyocellular lipotoxicity, cell death, alterations in mitochondrial oxidative capacity, left ventricular systolic and diastolic function, or arrhythmias could possibly explain the mortality seen in the UCP3−/− mice.

Fig. 3.

Survival curve. WT and UCP3−/− mice were maintained on a high-fat diet for a period of 2 weeks. During the last 8 days of the dietary intervention, mice received either saline or etomoxir by daily i.p. injections. All saline-treated animals survived the complete intervention period, whereas 2 out of 19 WT mice and 6 out of 24 UCP3−/− died upon etomoxir treatment

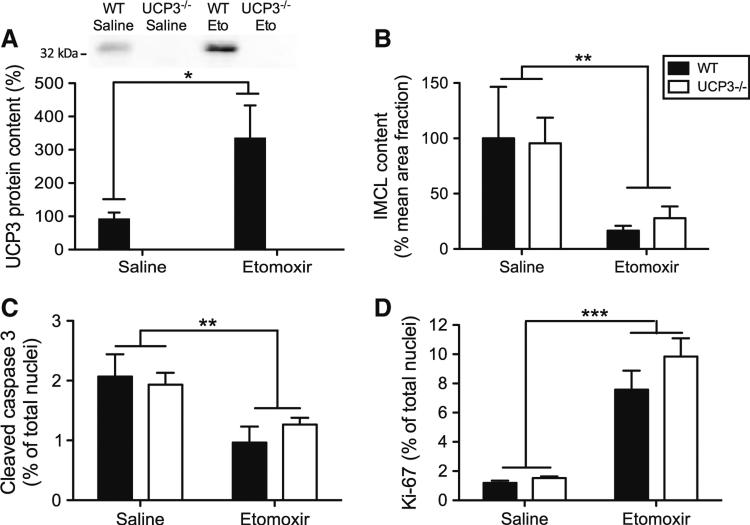

Intracardiomyocellular lipotoxicity, apoptosis, fibrosis and proliferation

Analogous to the increase in skm, etomoxir treatment resulted in a ~fourfold increase in UCP3 protein levels in the heart of the WT animals (Fig. 4a, P < 0.05), whereas no UCP3 was detected in UCP3−/− mice. We were able to collect tissue from one of the two WT mice that died upon etomoxir, and interestingly cardiac UCP3 protein content in this etomoxir-treated mouse was very low (~sevenfold reduction compared with average cardiac UCP3 protein content in the WT group, data not shown). This might suggest that cardiac UCP3 has beneficial effects on survival rate under lipid-challenged conditions. We previously showed that high levels of UCP3 can protect against age-induced increases in ROS production [23] and the redox balance is known to play an important role in cardioprotection [25, 41]. Therefore, we investigated whether the increased mortality in UCP3−/− mice upon etomoxir treatment could be due to cardiac lipotoxicity. However, in contrast to skm, inhibition of CPT1 by etomoxir resulted in a ~fourfold lowering of lipid content in the heart (Fig. 4b, P < 0.01), independent of genotype. No genotype, etomoxir or genotype × etomoxir interaction effects were found for the amount of cardiac HNE lipid peroxidation products (Fig. 5e), indicating no difference in oxidative damage between UCP3−/− mice compared with their WT littermates. Additionally, we found that etomoxir decreased the percentage of caspase-3 positive nuclei (Fig. 4c, P < 0.01), suggesting less apoptosis in the hearts of etomoxir-treated animals independent of the genotype. No signs of fibrosis were found as Sirius red staining did not show any abnormalities (data not shown). Ki-67 positive intracardiac cell number was elevated upon etomoxir treatment (Fig. 4d, P < 0.001) indicating increased cell proliferation, but again no genotype or genotype × etomoxir interaction effect was observed. These data indicate that neither cardiac lipid content, apoptosis, fibrosis nor impaired cell proliferation could directly explain the increased mortality in the HF diet-fed UCP3−/− animals upon etomoxir treatment.

Fig. 4.

Lack of UCP3 does not lead to cardiac lipotoxicity. a Quantification of immunoblot of UCP3 protein in cardiac muscle of mice (WT saline n = 7, WT etomoxir n = 6). The average amount of UCP3 in saline-treated WT mice was set to 100 %. Etomoxir intervention resulted in an increased UCP3 protein content in WT mice. UCP3 protein was not detected in cardiac tissue of UCP3−/− mice. Quantification of the histological stained cardiac fractions showed a significant decrease upon etomoxir treatment in the content of both intramyocellular lipids (IMCL) (n = 7–8 per group) (b) as well as the amount of cleaved-caspase three positive nuclei (n = 3–6 per group) (c). The number of Ki67 positive intracardiac cells increased after etomoxir treatment (n = 6–8 per group) (d). IMCL values were analyzed as percentage positive Oil Red O-stained area per mean cell surface area and are expressed as mean ± SE with WT saline mice set to 100 %. The number of nuclei positive for cleaved-caspase-3 was expressed as a percentage of immunopositive nuclei and are expressed as mean ± SE. Values are expressed as mean ± SE. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 by 2-way Anova analyses

Fig. 5.

Etomoxir inhibited CPT1-dependent mitochondrial respiration upon fatty acid substrates in IMF fractions. UCP3 ablation does not affect cardiac mitochondrial oxidative capacity. State 3, state 4o and state U (uncoupled) mitochondrial respiration was measured in subsarcolemmal (SS) and intramyofibrillar (IMF) cardiac mitochondria of WT and UCP3−/− mice treated with saline or etomoxir. Mitochondrial fractions were separated into IMF (a, c) and SS (b, d) fractions. Palmitoyl CoA + carnitine (a, b) and pyruvate (c, d) were used as substrates. Cardiac mitochondrial protein concentrations were 0.05 mg/ml for all respiratory measurements. Mitochondrial respiration is expressed as nmol/mg mitochondrial protein/min. e Representative immunoblot and quantification of 4-HNE protein adducts. Values are expressed as mean ± SE. *P < 0.05, by 2-way ANOVA analyses. (n = 4–7 per group)

Cardiac mitochondrial oxidative capacity

Next, we tested if lack of UCP3 affected intrinsic mitochondrial function under lipid-challenged conditions. No significant genotype, etomoxir or genotype × etomoxir interaction effects were detected on the content of any of the complexes of the oxidative phosphorylation system in the heart (Table 3 supplemental), implying similar cardiac mitochondrial densities in all groups. After mitochondrial isolation and separation, the amount of subsarcolemmal (SS) mitochondria was larger in comparison to the amount of intramyofibrillar (IMF) mitochondria (P < 0.001), regardless the genotype or intervention (data not shown).

Respirometry measurements in cardiac IMF mitochondria revealed a reduction in ADP-driven (state 3) (62 %, P < 0.001), leak (state 4o) (29 %, P < 0.05), and uncoupled (state U) (74 %, P < 0.001) mitochondrial respiration upon etomoxir in the presence of palmitoyl-CoA + carnitine (Fig. 5a), i.e., requiring CPT1. This reduction in mitochondrial respiration upon etomoxir was irrespective of the genotype, implying that UCP3 does not play a key role in fatty acid oxidation in cardiac mitochondria. Of note, in agreement with previous data [27, 31], we showed that IMF mitochondria exhibit higher respiratory rates compared with SS mitochondria. We could not detect an etomoxir effect in the SS mitochondrial fractions (Fig. 5b). In contrast, upon a glycolytic-derived substrate, pyruvate, etomoxir resulted in 58 % higher oxygen consumption in state 3 (P = 0.01) and 51 % increased uncoupled respiration (P < 0.01) of SS mitochondria, without any effect in IMF mitochondria (Fig. 5c, d). Most important, however, again no genotype or genotype × etomoxir interaction was found.

Overall, our data confirm that etomoxir indeed induces an inhibition of cardiac mitochondrial fat oxidation. However, because the level of inhibition was similar between the mice with and without UCP3, the increased mortality in the UCP3−/− mice could not be explained by a lower intrinsic cardiac mitochondrial oxidative capacity.

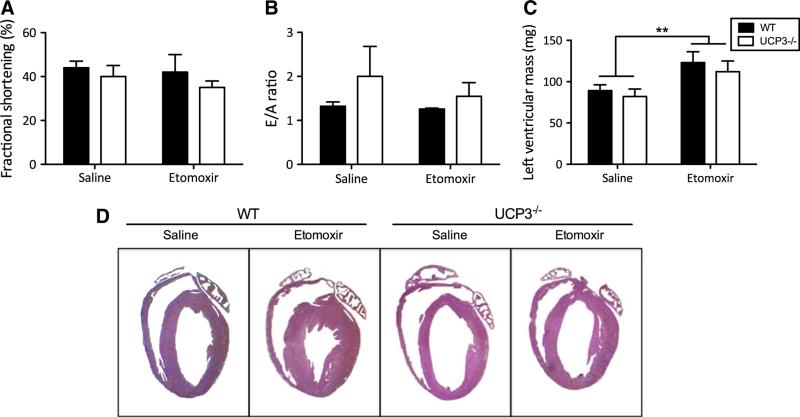

Cardiac function and remodeling

We next determined if lack of UCP3 under lipid-challenged conditions affects cardiac function and morphology. To this end, transthoracic echocardiography was performed in a subset of both WT and UCP3−/− mice. Analysis of echocardiography data (Table 4 supplemental) revealed no significant effect of etomoxir on left ventricle systolic function, assessed by fractional shortening (Fig. 6a) in WT or in UCP3−/− mice. In line with the data on systolic function, no difference in diastolic function, assessed by E/A ratio (Fig. 6b), was found between the groups.

Fig. 6.

Lack of UCP3 does not affect cardiac function. Transthoracic echocardiography characteristics in WT and UCP3−/− mice treated with saline or etomoxir of a left ventricular fractional shortening (%), b E/A ratio, and c left ventricular mass (mg). d Representative images of H&E staining of hearts that were arrested in diastole. Etomoxir treatment for 8 days resulted into cardiac hypertrophy in both, WT and UCP3−/− mice. Data are presented as mean ± S.E. **P = 0.01, by 2-way ANOVA analyses. (n = 4 per group)

Data on left ventricular mass (P = 0.01; Fig. 6c) as well as H&E staining of cardiac tissue (Fig. 6d) showed that the etomoxir intervention induced hypertrophy in both WT and UCP3−/− mice. This result implies that UCP3 does not protect against cardiac hypertrophy under lipid-challenged conditions induced by a HF diet combined with etomoxir.

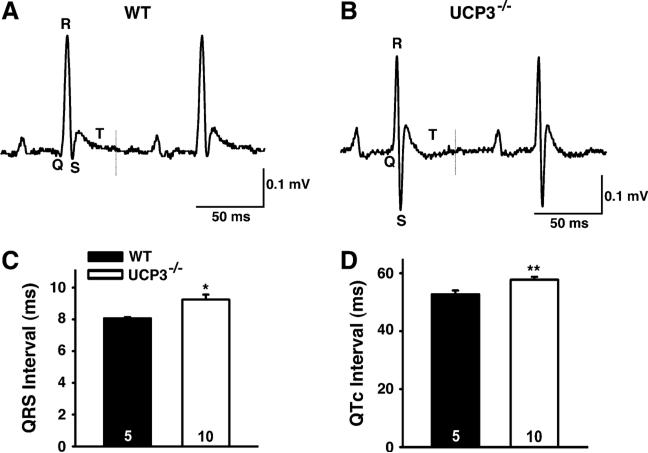

UCP3 deficiency predisposes to potentially fatal ventricular arrhythmias

Since UCP3−/− animals do not develop alterations in cardiac function and/or morphology that could directly explain the increased prevalence of sudden death in UCP3−/− mice, we tested if UCP3 deficiency under lipid-challenged conditions results in electrophysiological abnormalities. Therefore, we recorded surface ECG in anesthetized animals 1 hour after etomoxir injection. We found that UCP3−/− animals exhibited significantly longer QRS intervals than WT mice (Fig. 7a–c). Furthermore, QTc intervals were significantly prolonged in UCP3−/− mice when compared with WT (Fig. 7d). No other electrical parameters recorded were different between the two groups (Table 5 supplemental). These data suggest that ablation of UCP3 results in delayed ventricular conduction and prolonged repolarization, both of which could promote arrhythmogenesis and sudden cardiac death.

Fig. 7.

Representative ECG recordings of QRS intervals of WT (a) and UCP3−/− (b) mice. Measurements were made in anesthetized WT and UCP3−/− animals at 1 hour after etomoxir i.p. injection. c Quantification of the QRS intervals, and d QTc intervals (WT n = 5, UCP3−/− n = 10)

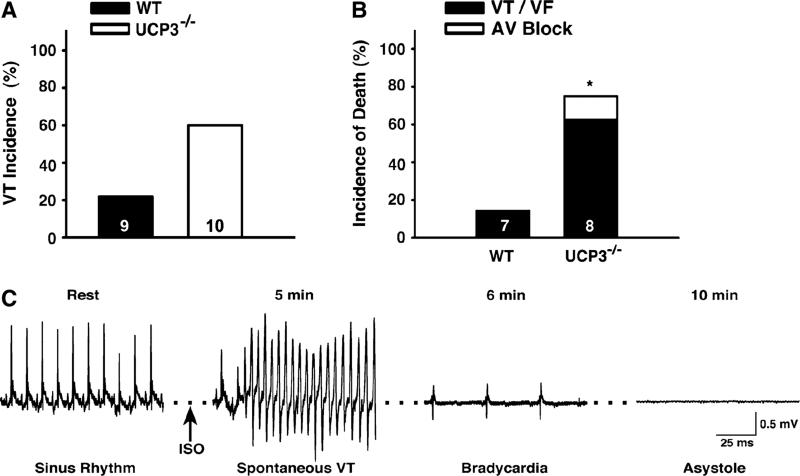

Given that a prolonged QT interval creates a predisposition to arrhythmias, we hypothesized that UCP3−/− mice are more susceptible to ventricular tachycardia (VT). To investigate this, we performed in vivo intracardiac electrophysiology studies, during which a catheter was inserted into the right ventricle via the right jugular vein. Programmed electrical stimulation (PES) was performed to determine arrhythmia susceptibility in WT and UCP3−/− mice. Double extrastimuli pacing induced reproducible sustained VT in 60 % of UCP3−/− mice compared with 22 % of WT mice (Fig. 8a).

Fig. 8.

In vivo intracardiac electrophysiology studies in anesthetized WT and UCP3−/− animals at 1 hour after etomoxir i.p. injection. a Double extrastimuli pacing induced reproducible sustained ventricular tachycardia (VT). b Incidence of death upon double extrastimuli pacing in the presence of isoproterenol. c Recording of arrhythmia that resulted into asystole in UCP3−/− mouse upon etomoxir. (WT n = 9, UCP3−/− n = 10)

PES was repeated after administration of the beta-adrenergic receptor agonist isoproterenol. While 75 % of UCP3−/− mice died following pacing (63 % VT/VF; 12 % AVB), only 14 % of the WT mice died (P = 0.04; Fig. 8b). One UCP3−/− mouse experienced spontaneous VT within five minutes of injection that deteriorated into ventricular fibrillation (VF) and lasted for over 1 min. This arrhythmia episode eventually resulted in asystole (Fig. 8c), which suggests that UCP3 deficiency coupled with etomoxir and stress is sufficient to provoke sudden death.

Discussion

Mitochondrial uncoupling proteins are involved in the regulation of proton leak over the inner mitochondrial membrane. As such, the best-described uncoupling protein—UCP1—is able to dissipate energy as heat by increasing proton leak, a mechanism that is crucial for its function in thermoregulation in brown adipose tissue. In 1997, several homologues of UCP1 were identified, of which UCP3 is mainly expressed in skm and heart. So far, the exact physiological function of UCP3 has not yet been revealed, but is suggested to be involved in protection of mitochondrial function, particularly under lipid-challenged conditions [26]. To elucidate the role of UCP3, we here examined the effect of UCP3 ablation in a condition in which the dysbalance between the availability of fatty acids and the fatty acid oxidative capacity is maximized. For this, we subjected UCP3−/− animals to a HF diet and combined this with the administration of etomoxir to inhibit fat oxidation. Of note, both etomoxir and HF diet feeding have been shown to substantially upregulate UCP3 levels [10, 35, 36, 46]. We here report that lack of UCP3 did not identify a significant role for skm UCP3 in protection against lipid-induced mitochondrial dysfunction. However, UCP3 seemed to be crucial for the heart under lipid-challenged conditions as we demonstrated an increased susceptibility to arrhythmias in UCP3−/− mice, and an increased risk for sudden cardiac death.

Absence of UCP3 does not affect skeletal muscle lipotoxicity

To elucidate the role of UCP3 during lipid-challenged conditions, we investigated the effect of etomoxir treatment combined with HF diet feeding on skm energy metabolism in UCP3−/− and WT mice. As anticipated, the etomoxir intervention resulted in increased skm lipid accumulation (fourfold) and a reduction in fat oxidative capacity, without a genotype effect. This data complements a previous study in which we observed that the absence of UCP3 did not alter mitochondrial function upon acute ex vivo exposure of isolated skm mitochondria to palmitate [24]. Based on these previous results, we hypothesized that longer-term ablation of UCP3 might reveal its role in the prevention of lipotoxicity. So far, many hypotheses about the function of UCP3 suggest mitochondrial protection against lipid-induced stress; e.g., protection against lipotoxicity and oxidative damage via control of reactive oxygen species production [3], or via fatty acid anion transport [37]. However, our results do not support an important beneficial role for skm UCP3 in the protection against skm lipotoxicity. During our experiments on skm metabolism, we did, however, observe that 25 % of mice lacking UCP3 died shortly after etomoxir administration. This suggests that UCP3 may be more important in the prevention of cardiac lipotoxicity. Indeed, previous studies showed altered cardiac UCP3 expression levels in response to metabolic stress in the heart [22, 29], further supporting our hypothesis.

Lack of UCP3 does not affect cardiac mitochondrial respiratory capacity

Preservation of mitochondrial function and structural integrity has been postulated to be essential for cardio-protection [32, 48]. Therefore, to elucidate the role of UCP3 on cardiac metabolism under lipid-challenged conditions, we performed a detailed analysis of cardiac mitochondrial respiratory capacity in UCP3−/− and WT mice. As for skm, we confirmed etomoxir administration in mice to be effective as was shown by a ~60 % decline in cardiac mitochondrial respiration upon a separate addition of palmitoyl-CoA and carnitine substrates, in the IMF fraction. Cardiac SS mitochondria showed no etomoxir-induced inhibition of palmitoyl-CoA plus carnitine fuelled mitochondrial respiration. Greater rates of fatty acid oxidation, as well as higher enzymatic activity of CPT1, have previously been shown in rat cardiac IMF mitochondria, compared with SS mitochondria [12] and could explain the observed fractional differences. Etomoxir treatment also led to ~60 % higher respiratory capacity upon pyruvate, but only in SS mitochondria suggesting that respiration in SS mitochondria might be able to compensate for the decreased fatty acid respiratory capacity [20, 30]. Most important, however, no genotype differences were observed illustrating that lack of UCP3 does not affect cardiac mitochondrial respiratory capacity, neither on fatty acid- nor on glycolytic-derived substrates. Moreover, as we observed higher mortality rates in UCP3−/− mice, our data imply that cardiac mitochondrial dysfunction is not the main mechanism contributing to sudden cardiac death in these animals.

Lack of UCP3 does not affect cardiac lipotoxicity or cell death

Interestingly, in contrast to our findings in skm, cardiac lipid content was decreased rather than increased upon etomoxir. Possibly, CPT1b is not the major rate-controlling site in total cardiac long chain fatty acid flux [17]. Again, the etomoxir effect on cardiac lipid content was independent of the genotype, illustrating that UCP3 does not seem to affect lipid accumulation in the heart. In line with this, lack of UCP3 in cardiac muscle did not affect the accumulation of lipid peroxidation products, a marker of oxidative stress. Also markers for apoptosis, fibrosis or proliferation of connective tissue were not altered in UCP3−/− mice. Based on these data, we conclude that cardiac lipotoxicity was not the cause for the sudden death in the etomoxir-treated UCP3−/− mice.

Effect of UCP3 on cardiac functional and electrophysiological characteristics

Since no increased signs of lipotoxicity or decreased mitochondrial respiratory capacity could be detected in cardiac tissue of UCP3−/− mice treated with etomoxir, we applied echocardiography in WT and UCP3−/− mice on a HF diet with etomoxir. Although these experiments confirmed higher mortality in UCP3−/− mice, we could not detect morphological or functional differences in systolic or diastolic cardiac function that could explain the sudden cardiac death in these animals.

Cardiac arrhythmias represent a major complication associated with diabetes and they can lead to sudden cardiac death [1, 7]. Interestingly, it was recently demonstrated that UCP3 expression is required to prevent ischemia reperfusion arrhythmias in addition to preventing contractile dysfunction [26]. This data implies a protective role for UCP3 against cardiac arrhythmias. Although in the present study no systolic or diastolic functional defects were detected, we explored the possibility whether lack of UCP3 could influence the electrophysiological characteristics of the heart after a lipid challenge. We recorded surface ECGs and found prolonged QTc and QRS intervals in UCP3−/− compared with WT mice. QT prolongation has been indicated as an accurate predictor of increased mortality in diabetes patients [14, 45] and is also more frequently reported in obesity [28]. Our data show that upon lipid challenge, mice lacking UCP3 have an enlarged time interval that is required for completing myocardial depolarization and repolarization. This suggests these mice have an increased susceptibility to arrhythmias, most likely due to (extensive) cardiac remodeling associated with changes in repolarizing currents. Indeed, programmed electrical stimulation experiments supported this theory, as double extrastimuli pacing induced sustained ventricular tachycardia in 60 % of UCP3−/− mice compared with 22 % of WT mice. Nevertheless, it remains to be confirmed that the spontaneous sudden death events were caused by cardiac arrest.

To our knowledge, the present study is the first in vivo study that demonstrates the importance of UCP3 in preventing arrhythmias under lipid-challenged conditions. Diabetes patients are at significantly higher risk of developing cardiomyopathy and heart failure compared with non-diabetics. Although the exact pathogenesis of diabetic cardiomyopathy is still poorly understood, alterations in lipid metabolism have been suggested to be an important mediator [43]. In this context, patients and genetically altered mice with defects in fat metabolism, i.e., infants with very long chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (VLCAD) deficiency [39] and VLCAD null mice [47] have been characterized by prolonged QT intervals, ventricular tachycardia or fatal arrhythmias similar to the etomoxir-administered UCP3−/− mice. In VLCAD null mice, abnormal Ca2+ handling is suggested as a possible molecular mechanism of arrhythmias [47]. Given recent hypotheses on a role for UCP3 in cellular Ca2+ handling [6, 8], it is tempting to speculate that modulation of repolarization in the UCP3−/− mice results from an attempt of cardiomyocytes to maintain Ca2+ homeostasis. Indeed, enhanced SR Ca leak has been shown to promote arrhythmias in other mutant mouse models [44].

Although human data on UCP3 levels in cardiac tissue are limited, UCP3 protein levels are markedly reduced in skm of type 2 diabetes patients [13, 34]. Our present study demonstrates a clear link between disturbed fat metabolism, UCP3 protein levels, and the incidence of cardiomyopathies and sudden death. Future studies should examine if cardiac UCP3 protein levels are low in (diabetes) patients who died from sudden cardiac death. Hence, UCP3 might be a novel therapeutic target for diabetic cardiomyopathy.

In conclusion, our findings indicate that even under severe in vivo lipid-challenged conditions, skm UCP3 does not play a major role in the preservation of skm energy metabolism. Our data in the heart, however, suggest that UCP3 may be crucial in protection against the development of arrhythmias and hence sudden cardiac death. Particularly in light of metabolic diseases like obesity, diabetes and heart failure, it will be interesting to further explore the impact of UCP3 in humans in prevention of arrhythmias under cardiac stress conditions.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Mary-Ellen Harper, Dr. David Marcinek and Dr. Michael Siegel for kindly providing us with the mice. This study was supported by The Netherlands Organization for Health Research & Development (ZonMw) (grant 9120.6050). M.N. is further supported by the Kootstra-Talent Fellowship program from the Maastricht University Medical Centre, Maastricht, The Netherlands. X.H.T.W. is an American Heart Association Established Investigator (grant 13EIA14560061), and is supported by NIH grants (HL089598, HL091947, and HL117641), a Muscular Dystrophy Association grant (186530), and the Juanita P. Quigley Endowed Chair in Cardiology (at Baylor College of Medicine). E.M. was supported by a supplement to R01-HL089598-04S1.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00395-014-0447-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Conflict of interest None.

Contributor Information

Miranda Nabben, Department of Human Biology, NUTRIM School for Nutrition, Toxicology and Metabolism, Maastricht University Medical Centre, PO Box 616, 6200 MD Maastricht, The Netherlands; Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, Mitochondria and Metabolism Center, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA.

Bianca W. J. van Bree, Department of Human Biology, NUTRIM School for Nutrition, Toxicology and Metabolism, Maastricht University Medical Centre, PO Box 616, 6200 MD Maastricht, The Netherlands

Ellen Lenaers, Department of Human Movement Sciences, NUTRIM School for Nutrition, Toxicology and Metabolism, Maastricht University Medical Centre, Maastricht, The Netherlands.

Joris Hoeks, Department of Human Biology, NUTRIM School for Nutrition, Toxicology and Metabolism, Maastricht University Medical Centre, PO Box 616, 6200 MD Maastricht, The Netherlands.

Matthijs K. C. Hesselink, Department of Human Movement Sciences, NUTRIM School for Nutrition, Toxicology and Metabolism, Maastricht University Medical Centre, Maastricht, The Netherlands

Gert Schaart, Department of Human Movement Sciences, NUTRIM School for Nutrition, Toxicology and Metabolism, Maastricht University Medical Centre, Maastricht, The Netherlands.

Marion J. J. Gijbels, Department of Molecular Genetics, CARIM School for Cardiovascular Research, Maastricht University Medical Centre, Maastricht, The Netherlands

Jan F. C. Glatz, Department of Molecular Genetics, CARIM School for Cardiovascular Research, Maastricht University Medical Centre, Maastricht, The Netherlands

Gustavo J. J. da Silva, Department of Cardiology, CARIM School for Cardiovascular Research, Maastricht University Medical Centre, Maastricht, The Netherlands

Leon J. de Windt, Department of Cardiology, CARIM School for Cardiovascular Research, Maastricht University Medical Centre, Maastricht, The Netherlands

Rong Tian, Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, Mitochondria and Metabolism Center, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, USA.

Elise Mike, Department of Molecular Physiology and Biophysics and Medicine (Cardiology), Cardiovascular Research Institute, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, USA.

Darlene G. Skapura, Department of Molecular Physiology and Biophysics and Medicine (Cardiology), Cardiovascular Research Institute, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, USA

Xander H. T. Wehrens, Department of Molecular Physiology and Biophysics and Medicine (Cardiology), Cardiovascular Research Institute, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, USA

Patrick Schrauwen, Department of Human Biology, NUTRIM School for Nutrition, Toxicology and Metabolism, Maastricht University Medical Centre, PO Box 616, 6200 MD Maastricht, The Netherlands.

References

- 1.Bergner DW, Goldberger JJ. Diabetes mellitus and sudden cardiac death: what are the data? Cardiol J. 2010;17:117–129. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boudina S, Han YH, Pei S, Tidwell TJ, Henrie B, Tuinei J, Olsen C, Sena S, Abel ED. UCP3 regulates cardiac efficiency and mitochondrial coupling in high fat-fed mice but not in leptindeficient mice. Diabetes. 2012;61:3260–3269. doi: 10.2337/db12-0063. doi:10.2337/db12-0063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brand MD, Affourtit C, Esteves TC, Green K, Lambert AJ, Miwa S, Pakay JL, Parker N. Mitochondrial superoxide: production, biological effects, and activation of uncoupling proteins. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;37:755–767. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.05.034. doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brand MD, Pamplona R, Portero-Otin M, Requena JR, Roebuck SJ, Buckingham JA, Clapham JC, Cadenas S. Oxidative damage and phospholipid fatty acyl composition in skeletal muscle mitochondria from mice underexpressing or over-expressing uncoupling protein 3. Biochem J. 2002;368:597–603. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021077. doi:10.1042/BJ20021077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chow L, From A, Seaquist E. Skeletal muscle insulin resistance: the interplay of local lipid excess and mitochondrial dysfunction. Metabolism. 2010;59:70–85. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2009.07.009. doi:10.1016/j.metabol.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Marchi U, Castelbou C, Demaurex N. Uncoupling protein 3 (UCP3) modulates the activity of Sarco/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2?-ATPase (SERCA) by decreasing mitochondrial ATP production. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:32533–32541. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.216044. doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.216044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Erickson JR, Pereira L, Wang L, Han G, Ferguson A, Dao K, Copeland RJ, Despa F, Hart GW, Ripplinger CM, Bers DM. Diabetic hyperglycaemia activates CaMKII and arrhythmias by O-linked glycosylation. Nature. 2013;502:372–376. doi: 10.1038/nature12537. doi:10.1038/nature12537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graier WF, Trenker M, Malli R. Mitochondrial Ca2?, the secret behind the function of uncoupling proteins 2 and 3? Cell Calcium. 2008;44:36–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2008.01.001. doi:10.1016/j.ceca.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hagen T, Zhang CY, Slieker LJ, Chung WK, Leibel RL, Lowell BB. Assessment of uncoupling activity of the human uncoupling protein 3 short form and three mutants of the uncoupling protein gene using a yeast heterologous expression system. FEBS Lett. 1999;454:201–206. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00811-x. (S0014-5793(99)00811-X [pii]) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hesselink MK, Greenhaff PL, Constantin-Teodosiu D, Hultman E, Saris WH, Nieuwlaat R, Schaart G, Kornips E, Schrauwen P. Increased uncoupling protein 3 content does not affect mitochondrial function in human skeletal muscle in vivo. J Clin Invest. 2003;111:479–486. doi: 10.1172/JCI16653. doi:10.1172/JCI16653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoeks J, Hesselink MK, Russell AP, Mensink M, Saris WH, Mensink RP, Schrauwen P. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma coactivator-1 and insulin resistance: acute effect of fatty acids. Diabetologia. 2006;49:2419–2426. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0369-2. doi:10.1007/s00125-006-0369-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holloway GP, Snook LA, Harris RJ, Glatz JF, Luiken JJ, Bonen A. In obese Zucker rats, lipids accumulate in the heart despite normal mitochondrial content, morphology and long-chain fatty acid oxidation. J Physiol. 2011;589:169–180. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.198663. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2010.198663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krook A, Digby J, O'Rahilly S, Zierath JR, Wallberg-Henriksson H. Uncoupling protein 3 is reduced in skeletal muscle of NIDDM patients. Diabetes. 1998;47:1528–1531. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.47.9.1528. doi:10.2337/diabetes.47.9.1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Linnemann B, Janka HU. Prolonged QTc interval and elevated heart rate identify the type 2 diabetic patient at high risk for cardiovascular death. The Bremen Diabetes Study. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2003;111:215–222. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-40466. doi:10.1055/s-2003-40466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lopaschuk GD, McNeil GF, McVeigh JJ. Glucose oxidation is stimulated in reperfused ischemic hearts with the carnitine palmitoyltransferase 1 inhibitor, Etomoxir. Mol Cell Biochem. 1989;88:175–179. doi: 10.1007/BF00223440. doi:10.1007/BF00223440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lopaschuk GD, Wall SR, Olley PM, Davies NJ. Etomoxir, a carnitine palmitoyltransferase I inhibitor, protects hearts from fatty acid-induced ischemic injury independent of changes in long chain acylcarnitine. Circ Res. 1988;63:1036–1043. doi: 10.1161/01.res.63.6.1036. doi:10.1161/01.RES.63.6.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luiken JJ, Niessen HE, Coort SL, Hoebers N, Coumans WA, Schwenk RW, Bonen A, Glatz JF. Etomoxir-induced partial carnitine palmitoyltransferase-I (CPT-I) inhibition in vivo does not alter cardiac long-chain fatty acid uptake and oxidation rates. Biochem J. 2009;419:447–455. doi: 10.1042/BJ20082159. doi:10.1042/BJ20082159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Millet L, Vidal H, Andreelli F, Larrouy D, Riou JP, Ricquier D, Laville M, Langin D. Increased uncoupling protein-2 and -3 mRNA expression during fasting in obese and lean humans. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:2665–2670. doi: 10.1172/JCI119811. doi:10.1172/JCI119811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mingrone G, Rosa G, Greco AV, Manco M, Vega N, Hesselink MK, Castagneto M, Schrauwen P, Vidal H. Decreased uncoupling protein expression and intramyocytic triglyceride depletion in formerly obese subjects. Obes Res. 2003;11:632–640. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.91. doi:10.1038/oby.2003.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mollica MP, Lionetti L, Crescenzo R, D'Andrea E, Ferraro M, Liverini G, Iossa S. Heterogeneous bioenergetic behaviour of subsarcolemmal and intermyofibrillar mitochondria in fed and fasted rats. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:358–366. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-5443-2. doi:10.1007/s00018-005-5443-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murray AJ, Anderson RE, Watson GC, Radda GK, Clarke K. Uncoupling proteins in human heart. Lancet. 2004;364:1786–1788. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17402-3. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17402-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murray AJ, Cole MA, Lygate CA, Carr CA, Stuckey DJ, Little SE, Neubauer S, Clarke K. Increased mitochondrial uncoupling proteins, respiratory uncoupling and decreased efficiency in the chronically infarcted rat heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008;44:694–700. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.01.008. doi:10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nabben M, Hoeks J, Briede JJ, Glatz JF, Moonen-Kornips E, Hesselink MK, Schrauwen P. The effect of UCP3 over-expression on mitochondrial ROS production in skeletal muscle of young versus aged mice. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:4147–4152. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.11.016. doi:10.1016/j.febslet.2008.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nabben M, Shabalina IG, Moonen-Kornips E, van Beurden D, Cannon B, Schrauwen P, Nedergaard J, Hoeks J. Uncoupled respiration, ROS production, acute lipotoxicity and oxidative damage in isolated skeletal muscle mitochondria from UCP3-ablated mice. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1807:1095–1105. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.04.003. doi:10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nickel A, Loffler J, Maack C. Myocardial energetics in heart failure. Basic Res Cardiol. 2013;108:358. doi: 10.1007/s00395-013-0358-9. doi:10.1007/s00395-013-0358-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ozcan C, Palmeri M, Horvath TL, Russell KS, Russell RR., 3rd Role of uncoupling protein 3 in ischemia-reperfusion injury, arrhythmias, and preconditioning. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2013;304:H1192–H1200. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00592.2012. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00592.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Palmer JW, Tandler B, Hoppel CL. Biochemical properties of subsarcolemmal and interfibrillar mitochondria isolated from rat cardiac muscle. J Biol Chem. 1977;252:8731–8739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Poirier P, Giles TD, Bray GA, Hong Y, Stern JS, Pi-Sunyer FX, Eckel RH. Obesity and cardiovascular disease: patho-physiology, evaluation, and effect of weight loss: an update of the 1997 American Heart Association Scientific Statement on Obesity and Heart Disease from the Obesity Committee of the Council on Nutrition, Physical Activity, and Metabolism. Circulation. 2006;113:898–918. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.171016. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.171016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Razeghi P, Young ME, Ying J, Depre C, Uray IP, Kolesar J, Shipley GL, Moravec CS, Davies PJ, Frazier OH, Taegtmeyer H. Downregulation of metabolic gene expression in failing human heart before and after mechanical unloading. Cardiology. 2002;97:203–209. doi: 10.1159/000063122. doi:10.1159/000063122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ritov VB, Menshikova EV, He J, Ferrell RE, Goodpaster BH, Kelley DE. Deficiency of subsarcolemmal mitochondria in obesity and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2005;54:8–14. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.1.8. (54/1/8 [pii]) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Riva A, Tandler B, Loffredo F, Vazquez E, Hoppel C. Structural differences in two biochemically defined populations of cardiac mitochondria. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H868–H872. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00866.2004. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00866.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosca MG, Hoppel CL. Mitochondria in heart failure. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;88:40–50. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvq240. doi:10.1093/cvr/cvq240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Russell AP, Somm E, Praz M, Crettenand A, Hartley O, Melotti A, Giacobino JP, Muzzin P, Gobelet C. Deriaz O (2003) UCP3 protein regulation in human skeletal muscle fibre types I, IIa and IIx is dependent on exercise intensity. J Physiol. 2003;550:855–861. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.040162. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2003.040162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schrauwen P, Hesselink MK, Blaak EE, Borghouts LB, Schaart G, Saris WH, Keizer HA. Uncoupling protein 3 content is decreased in skeletal muscle of patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2001;50:2870–2873. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.50.12.2870. doi:10.2337/diabetes.50.12.2870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schrauwen P, Hinderling V, Hesselink MK, Schaart G, Kornips E, Saris WH, Westerterp-Plantenga M, Langhans W. Etomoxir-induced increase in UCP3 supports a role of uncoupling protein 3 as a mitochondrial fatty acid anion exporter. FASEB J. 2002;16:1688–1690. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0275fje. doi:10.1096/fj. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schrauwen P, Hoeks J, Schaart G, Kornips E, Binas B, Van De Vusse GJ, Van Bilsen M, Luiken JJ, Coort SL, Glatz JF, Saris WH, Hesselink MK. Uncoupling protein 3 as a mitochondrial fatty acid anion exporter. FASEB J. 2003;17:2272–2274. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0515fje. doi:10.1096/fj.03-0515fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schrauwen P, Saris WH, Hesselink MK. An alternative function for human uncoupling protein 3: protection of mitochondria against accumulation of nonesterified fatty acids inside the mitochondrial matrix. FASEB J. 2001;15:2497–2502. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0400hyp. doi:10.1096/fj.01-0400hyp. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schrauwen P, Troost FJ, Xia J, Ravussin E, Saris WH. Skeletal muscle UCP2 and UCP3 expression in trained and untrained male subjects. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1999;23:966–972. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801026. doi:10.1038/sj.ijo.0801026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Strauss AW, Powell CK, Hale DE, Anderson MM, Ahuja A, Brackett JC, Sims HF. Molecular basis of human mitochondrial very-long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase deficiency causing cardiomyopathy and sudden death in childhood. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:10496–10500. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.23.10496. doi:10.1073/pnas.92.23.10496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Timmers S, Nabben M, Bosma M, van Bree B, Lenaers E, van Beurden D, Schaart G, Westerterp-Plantenga MS, Langhans W, Hesselink MK, Schrauwen-Hinderling VB, Schrauwen P. Augmenting muscle diacylglycerol and triacylglycerol content by blocking fatty acid oxidation does not impede insulin sensitivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:11711–11716. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206868109. doi:10.1073/pnas.1206868109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tullio F, Angotti C, Perrelli MG, Penna C, Pagliaro P. Redox balance and cardioprotection. Basic Res Cardiol. 2013;108:392. doi: 10.1007/s00395-013-0392-7. doi:10.1007/s00395-013-0392-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Turcani M, Rupp H. Etomoxir improves left ventricular performance of pressure-overloaded rat heart. Circulation. 1997;96:3681–3686. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.10.3681. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.96.10.3681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van de Weijer T, Schrauwen-Hinderling VB, Schrauwen P. Lipotoxicity in type 2 diabetic cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc Res. 2011;92:10–18. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvr212. doi:10.1093/cvr/cvr212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van Oort RJ, McCauley MD, Dixit SS, Pereira L, Yang Y, Res-press JL, Wang Q, De Almeida AC, Skapura DG, Anderson ME, Bers DM, Wehrens XH. Ryanodine receptor phosphorylation by calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II promotes life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias in mice with heart failure. Circulation. 2010;122:2669–2679. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.982298. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.982298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Veglio M, Sivieri R, Chinaglia A, Scaglione L, Cavallo-Perin P. QT interval prolongation and mortality in type 1 diabetic patients: a 5-year cohort prospective study. Neuropathy Study Group of the Italian Society of the Study of Diabetes Piemonte Affiliate. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:1381–1383. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.9.1381. doi:10.2337/diacare.23.9.1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weigle DS, Selfridge LE, Schwartz MW, Seeley RJ, Cummings DE, Havel PJ, Kuijper JL, BeltrandelRio H. Elevated free fatty acids induce uncoupling protein 3 expression in muscle: a potential explanation for the effect of fasting. Diabetes. 1998;47:298–302. doi: 10.2337/diab.47.2.298. doi:10.2337/diab.47.2.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Werdich AA, Baudenbacher F, Dzhura I, Jeyakumar LH, Kannankeril PJ, Fleischer S, LeGrone A, Milatovic D, Aschner M, Strauss AW, Anderson ME, Exil VJ. Polymorphic ventricular tachycardia and abnormal Ca2? handling in very-long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase null mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H2202–H2211. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00382.2006. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00382.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yan W, Zhang H, Liu P, Wang H, Liu J, Gao C, Liu Y, Lian K, Yang L, Sun L, Guo Y, Zhang L, Dong L, Lau WB, Gao E, Gao F, Xiong L, Wang H, Qu Y, Tao L. Impaired mitochondrial biogenesis due to dysfunctional adiponectin-AMPK-PGC-1alpha signaling contributing to increased vulnerability in diabetic heart. Basic Res Cardiol. 2013;108:329. doi: 10.1007/s00395-013-0329-1. doi:10.1007/s00395-013-0329-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.