The use of left ventricular assist devices (LVADs) as a therapeutic strategy for patients with end-stage heart failure continues to increase, particularly in patients ineligible for heart transplantation.1 The incidence of device malfunction with the newer generations of LVADs is low,1 yet prompt recognition and management of the different sources of device dysfunction is critical. We report an unusual case of drive-line (DL) dysfunction leading to pump stoppage 2 years after implantation of a HeartMate II (Thoratec Corp., Pleasanton, CA) LVAD.

A 47-year-old man with refractory, inotrope-dependent heart failure due to non-ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy underwent LVAD placement as a definitive therapy. The patient was not eligible for heart transplant due to morbid obesity, with a body mass index of 37 kg/m2. His post-LVAD course had been complicated by DL site infection with methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus, requiring incision and drainage of the DL space 20 and 22 months after implant, and use of long-term antibiotics.

Two years after device implant, and shortly after being connected to the power base unit (PBU) and system monitor for routine LVAD interrogation during a clinic visit, his LVAD alarm went off and few seconds later he collapsed. We were unable to obtain a blood pressure reading and LVAD sounds were absent. The monitor that had initially shown normal LVAD parameters now displayed a “no-flow” alert. The system controller was promptly exchanged without any effect. The patient’s LVAD power lead was reconnected to his external battery, which resulted in alarm deactivation, restoration of pump function and resolution of symptoms. He was transferred to the intensive care unit for additional evaluation.

In the intensive care unit, the patient remained asymptomatic and his vital signs were within normal limits. Once again, we attempted to interrogate his LVAD by connecting one of the power leads (white connector) to the PBU and system monitor; however, upon connecting to the PBU, a red heart alarm recurred, the patient developed severe chest pain and dyspnea, his arterial pressure waveform that initially showed no pulsatility became pulsatile, and auscultation of his precordium revealed absent LVAD hum confirming pump stoppage. The controller power lead was promptly reconnected to his external battery with resolution of the alarm, symptoms and restoration of LVAD function.

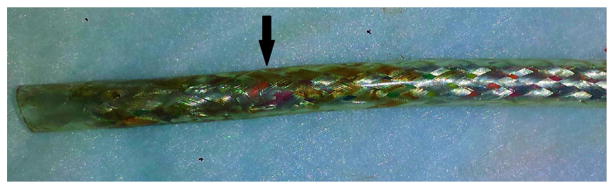

The device was thoroughly evaluated by Thoratec engineers and no abnormalities were found in the external batteries, power leads or system controller. This suggested malfunction of the DL. Abdominal X-ray films did not show any abnormalities of the DL. Using the DL fault detection system, the six individual wires of the DL were impedance tested for fracture; the tests were negative, suggesting that a “short-to-shield phenomenon” had occurred due to damage in the insulation of one of the DL internal wires. The power cable for the PBU was changed to an ungrounded cable and we were able to connect the LVAD to the PBU and monitor uneventfully. In an attempt to localize the “short-to-shield” site, the external portion of the DL was replaced by company engineers sequentially splicing and replacing redundant wires, at all times maintaining the power supply to the pump. This, however, did not resolve the issue and the patient underwent successful LVAD exchange 1 week later. Figure 1 shows the internal portion of the DL removed at the time of pump exchange, with the metal sheath physically compromised.

Figure 1.

Internal portion of the DL removed at the time of pump exchange. The metal sheath is physically compromised (arrow).

The HeartMate II LVAD is a second-generation, continuous-flow device with an improved design that allows for an extremely low bearing wear and an effective life of well beyond 10 years.2 Use of the HeartMate II in its current iteration in otherwise moribund patients with advanced HF has recently been shown to lead to 2-year survival of 62%.3 However, design improvements involving the external and internal connector strain relief of the DL are ongoing and have resulted in a significant reduction of DL failures associated with a major clinical event—from 6.2% to 2.2%.4 Yet, damage of the DL in patients supported with HeartMate II LVADs is the most common reason for pump exchanges, accounting for 47% of all replacements.5 One of the causes of DL failure is related to damage of the internal wiring of the DL, leading to the short-to-shield phenomenon, as was the case in our patient.

To better understand this phenomenon we must first review the basic components of the DL: The HeartMate II LVAD consists of an internal axial flow blood pump connected to an external system controller and two external power sources by means of a DL. The motor’s power is supplied by three phases and each phase is served by two redundant wires, with only one wire in each phase being essential for motor operation (Figure 2A and B). Each of these six wires is individually covered by a dielectric insulator and all six wires are covered by a metallic shield, which is covered by a plastic jacket. The function of the metallic shield is to reduce electrical noise and electromagnetic radiation that may interfere with other devices. The shield is grounded when the patient (power lead) is connected to the PBU and, although part of the approved LVAD design, it is not essential for pump operation (i.e., the PBU can be used with an ungrounded cable).

Figure 2.

(A) Actual PL demonstrating the six wires (*) that constitute the three phases by which the power is delivered to the motor; and the metallic shield (**). (B) Schematic representation of the three phases, with each phase served by two redundant wires. (C) Schematic representation of the short-to-shield phenomenon.

The insulation or any of the six wires itself can break resulting in DL malfunction and potentially in pump stoppage. If only one wire of any phase is affected either by insulation wear or wire fracture, the pump will continue to run as the redundant wire is still intact and the patient will remain asymptomatic. However, if the fault wire contacts the shield (short-to-shield phenomenon; Figure 2C), the pump will stop when the patient’s power lead is connected to the PBU as the grounded power cable will “leak” the current to the ground, causing a voltage drop in the pump. This failure mode can be eliminated by either maintaining the patient on batteries all the time or by using an ungrounded power cable for the PBU. In our patient, pump stoppage did not occur at home as he never used the PBU and decided to stay on batteries all the time after implantation, as “he didn’t like feeling tied up.” The use of an ungrounded power cable, however, may just be a temporizing measure for some patients as the pump may stop again if a second wire is damaged and contacts the first damaged wire.

Current technology allows an attempt to localize the short-to-shield phenomenon to the external portion of the DL. This is accomplished by first interrogating individual wires for complete fracture by impedance testing and X-ray, and then replacing the external part of the DL and connecting again to a grounded power source. If pump stoppage does not recur and physical damage to individual wires in the external DL portion is identified, it may be reasonable to assume that power can be safely maintained without exchanging the entire HeartMate II system. Of course, safety of such a repaired system cannot be guaranteed, and clinical circumstances, such as risk of reoperation and/or unrecognized damage to the internal portion of the DL, must be taken into consideration when deciding on pump replacement.

In conclusion, major DL dysfunction can lead to pump failure. Pump stoppage upon switching from battery to power base, that is, when grounding, should immediately alert the provider to the possibility of a short-to-shield. Failure to swiftly recognize the short-to-shield phenomenon and eliminate grounding sources may lead to pump stoppage, cardiovascular collapse and/or death.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

Y.N. and U.P.J. have received honoria from Thoratec Corporation (Pleasanton, CA). The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Kirklin JK, Naftel DC, Pagani FD, et al. Sixth INTERMACS annual report: a 10,000-patient database. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2014;33:555–64. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2014.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sundareswaran KS, Reichenbach SH, Masterson KB, et al. Low bearing wear in explanted HeartMate II left ventricular assist devices after chronic clinical support. ASAIO J. 2013;59:41–5. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0b013e3182768cfb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jorde UP, Kushwaha SS, Tatooles AJ, et al. Results of the destination therapy post-Food and Drug Administration approval study with a continuous flow left ventricular assist device: a prospective study using the INTERMACS registry (Interagency Registry for Mechanically Assisted Circulatory Support) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:1751–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.01.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalavrouziotis D, Tong MZ, Starling RC, et al. Percutaneous lead dysfunction in the HeartMate II left ventricular assist device. Ann Thorac Surg. 2014;97:1373–8. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moazami N, Milano CA, John R, et al. Pump replacement for left ventricular assist device failure can be done safely and is associated with low mortality. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;95:500–5. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2012.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]