Abstract

Purpose

A 40-year-old man with congenital midline defect and wide pubic symphysis diastasis secondary to bladder exstrophy presented with a massive incisional hernia resulting from complications of multiple prior abdominal repairs. Using a multi-disciplinary team of general, plastic, and urologic surgeons, we performed a complex hernia repair including creation of a pubic symphysis with rib graft for inferior fixation of mesh.

Methods

The skin graft overlying the peritoneum was excised, and the posterior rectus sheath mobilized, then re-approximated. The previously augmented bladder and urethra were mobilized into the pelvis, after which a rib graft was constructed from the 7th rib and used to create a symphysis pubis using a mortise joint. This rib graft was used to fix the inferior portion of a 20 × 25 cm porcine xenograft mesh in a retro-rectus position. With the defect closed, prior skin scars were excised and the wound closed over multiple drains.

Results

The patient tolerated the procedure well. His post-operative course was complicated by a vesico-cutaneous fistula and associated urinary tract and wound infections. This resolved by drainage with a urethral catheter and bilateral percutaneous nephrostomies. The patient has subsequently healed well with an intact hernia repair. The increased intra-abdominal pressure from his intact abdominal wall has been associated with increased stress urinary incontinence.

Conclusions

Although a difficult operation prone to serious complications, reconstruction of the symphysis pubis is an effective means for creating an inferior border to affix mesh in complex hernia repairs associated with bladder exstrophy.

Keywords: Bladder exstrophy, Rib graft, Pubic diastasis

Introduction

Bladder exstrophy is a complex congenital condition involving the abdominal wall, urinary and reproductive systems. It is part of the continuum of the exstrophy-epispadias complex and is thought to occur as a result of a defect in the embryological formation of the abdominal wall. Abnormalities of the cloacal membrane prevent formation of midline structures, and the eventual rupture of the membrane results in herniation and malformation of the bladder through this defect. Diastasis of the symphysis pubis, caused by malrotation of the developing pelvis, is coincident with bladder exstrophy [1, 2]. Even following repair in childhood, these patients frequently have recurrent or persistent diastasis [3].

Here, we report the case of a 40-year-old man with congenital bladder exstrophy and diastasis of the symphysis pubis, complicated by a giant incisional hernia following exploratory laparotomy for trauma (Fig. 1). Because the absence of a pubic symphysis prevented inferior fixation of mesh, we fashioned a pubic symphysis from a rib graft, providing a biological fixation point for a porcine allograft underlay repair.

Fig. 1.

A Pre-operative photograph showing a large traumatic parapubic hernia in the setting of repaired bladder exstrophy

Case report

The patient is a 40-year-old man with a complex history of abdominal wall repairs. He had congenital bladder exstrophy with wide pubic diastasis (Fig. 2) and had undergone a number of reconstructive operations including bladder augmentation and artificial urinary sphincter implantation to manage his baseline stress urinary incontinence. Following a motor vehicle collision in 2009, the enterocystoplasty perforated necessitating emergent laparotomy and repair. The tubing to his artificial urinary sphincter was accidentally transected during this operation rendering the cuff non-functional. Because of bowel edema at the time of operation, his abdomen was left open with interval closure over an Alloderm underlay mesh on postoperative day 4. The patient subsequently developed an infection of the inferior portion of his alloderm, which had failed to granulate. This segment was resected approximately 2 months post-operatively, and the patient was left with a fascial defect. A skin graft was subsequently placed over the well-granulated defect. Approximately 2 years following his traumatic injury, the patient presented for elective repair of his lower midline incisional hernia.

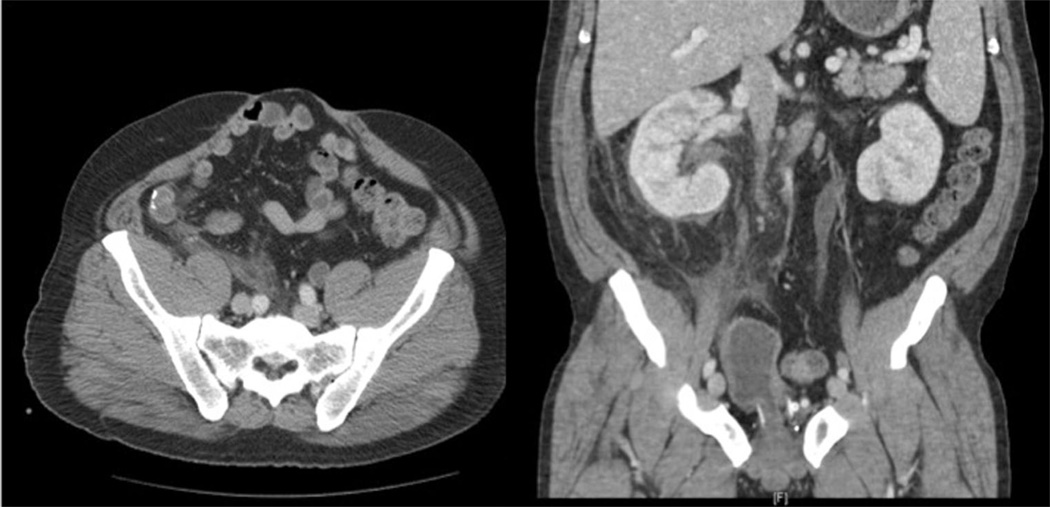

Fig. 2.

Computed axial tomography (CT) demonstrating the hernia sac and pubic diastasis

The repair began with excision of the skin graft overlying the peritoneum and the posterior rectus sheath mobilized, then re-approximated. The previously augmented bladder and urethra were mobilized into the pelvis. The defect in the pubic symphysis was measured at 10 cm.

A rib graft was then constructed from a 12 cm segment of the right 7th rib, harvested through a separate chest incision. The rib was used to create a symphysis pubis using mortise joints fixed in place with a long mandibular plate and locking screws (Fig. 3). This rib graft was used to fix the inferior portion of a single 20 × 25 cm sheet of porcine xenograft mesh (Strattice mesh, Life Cell Corporation, Bridgewater, NJ) in a retro-rectus position (Fig. 4). Biologic mesh was chosen because of the history of infection at the hernia site and the anticipated opening of the bladder lumen during the dissection. Maxon #0 stitches were used for fixation. To attach the mesh to the rib graft, holes were drilled in the graft and sutures were passed through these to affix the mesh. With the defect closed, prior skin scars were excised and the wound closed over multiple drains.

Fig. 3.

CT demonstrating the reconstructed pubic symphysis. Placement of a 7th rib bone graft with mortise joints created an inferior fixation point for a biologic mesh

Fig. 4.

Porcine xenograft biologic mesh placed in the retro-rectus position, with fixation to the fascia of the abdominal wall and inferiorly to the rib graft

The patient tolerated the procedure well. His post-operative course was complicated by a vesico-cutaneous fistula and associated urinary tract and wound infections. This resolved by drainage with a urethral catheter and bilateral percutaneous nephrostomies. The patient has subsequently healed well with an intact hernia repair (Fig. 5), though the increased intra-abdominal pressure from his intact abdominal wall resulted in increased stress urinary incontinence, as the tubing for his artificial urinary sphincter was damaged during the laparotomy in 2009. In August 2013, the bladder neck cuff for the artificial urinary sphincter eroded into his urethra. An abdominal incision was performed to remove all components of his artificial urinary sphincter. With the exception of a post-operative superficial wound seroma that required drainage, he recovered well from his surgery. His abdominal hernia has not recurred.

Fig. 5.

The patient’s abdomen several months following the repair, showing closure of the hernia defect and healing of incisions

Discussion

Parapubic hernia is a rare disorder requiring a complex repair. Previous reports detail a variety of approaches to the repair of these hernias [4–7]. Most allow fixation of mesh to an intact pubis, but in the case of pubic diastasis with bladder exstrophy no such anchor is available. A previous case report describes the inferior fixation of mesh to elements of the pelvic peritoneum, including the pelvic diaphragm, Cooper’s ligaments, and the arcuate pubic ligament, with the use of both an underlay and onlay mesh to create a dense fibrosis to create a firm anchor inferiorly [8]. This approach represents a modification of methods published by Bendavid for closure of parapubic hernias without congenital malformation [4].

A better alternative for fixation of mesh in a complex parapubic hernia may be the creation of a new pubis using bone graft. By creating a bony anchor for the inferior portion of the graft, while fixing the superior and lateral margins to the fascia of the rectus abdominus, we believe we were better able to distribute the force of intra-abdominal pressure. A similar approach was described by Seckiner et al. [9] for the treatment of a bladder hernia following a traumatic, rather than congenital, pubic symphyseal diastasis. In this case, the diastasis was just 2 cm and was closed using tibial bone grafts. Our approach, using a rib graft, allowed for a single operative field and provided a bone graft that required minimal modification to accommodate the wide pelvic defect. Although our case was complicated by trauma and multiple prior laparotomies, because most patients with bladder exstrophy have a widened pubic symphysis, this approach may be beneficial hernia repair in this population regardless of the etiology of the abdominal wall defect [3].

Despite the inadvertent disruption of his artificial urethral sphincter tubing during his emergent laparotomy for trauma, the patient remained continent following the laparotomy in 2009. This was secondary to the large abdominal wall hernia what kept his intra-abdominal pressure low to prevent stress incontinence. With repair of his abdominal wall hernia and return of his abdominal contents to the abdominal cavity, the associated increase in intra-abdominal pressure resulted in a return of moderate–severe stress urinary incontinence. He is contemplating a future urinary reconstruction, as a means to more effectively manage his bothersome stress urinary incontinence.

Although a difficult operation prone to serious complications, reconstruction of the symphysis pubis is an effective means for creating an inferior border to affix mesh in complex hernia repairs associated with bladder exstrophy. While the long-term duration of the repair is unknown, the use of a living bone graft as an inferior fixation point should make the repair in the setting of a complex congenital pelvic deformity similar in durability to a parapubic hernia repair in patients with an intact pubic symphysis.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest JK declares no conflict of interest.

JF declares no conflict of interest.

MJ declares no conflict of interest.

BV declares no conflict of interest.

HF declares no conflict of interest.

RG declares no conflict of interest.

JG declares no conflict of interest.

HE declares no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

J. E. Kohler, Department of Surgery, Harborview Medical Center, Box 359796, Seattle, WA 98104-2499, USA

J. S. Friedstat, Department of Surgery, Harborview Medical Center, Box 359796, Seattle, WA 98104-2499, USA

M. A. Jacobs, Department of Urology, University of Texas - Southwestern Medical School, Dallas, TX, USA

B. B. Voelzke, Department of Urology, Harborview Medical Center, Seattle, WA, USA

H. M. Foy, Department of Surgery, Harborview Medical Center, Box 359796, Seattle, WA 98104-2499, USA

R. W. Grady, Department of Urology, Seattle Children’s Hospital, Seattle, WA, USA

J. S. Gruss, Division of Plastic Surgery, Department of Surgery, Harborview Medical Center, Seattle, WA, USA

H. L. Evans, Email: hlevans@uw.edu, Department of Surgery, Harborview Medical Center, Box 359796, Seattle, WA 98104-2499, USA.

References

- 1.Coran AG, Caldamone A, Adzick NS, et al. Pediatric surgery, 2-Volume Set. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomalla JV, Rudolph RA, Rink RC, Mitchell ME. Induction of cloacal exstrophy in the chick embryo using the CO2 laser. J Urol. 1985;134:991–995. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)47573-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suson KD, Sponseller PD, Gearhart JP. Bony abnormalities in classic bladder exstrophy: the urologist’s perspective. J Pediatr Urol. 2013;9:112–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jpurol.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bendavid R. Incisional parapubic hernias. Surgery. 1990;108:898–901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yao S, Li J-Y. Treatment for incisional parapubic hernia: an experience of 25 cases. Am Surg. 2010;76:1420–1422. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Losanoff JE, Richman BW, Jones JW. Parapubic hernia: case report and review of the literature. Hernia. 2002;6:82–85. doi: 10.1007/s10029-002-0060-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hirasa T, Pickleman J, Shayani V. Laparoscopic repair of parapubic hernia. Arch Surg. 2001;136:1314–1317. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.136.11.1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moreno-Egea A, Campillo-Soto A, la Calle MC, et al. Incisional pubic hernia: treatment of a case with congenital malformation of the pelvis. Hernia. 2006;10:87–89. doi: 10.1007/s10029-005-0004-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seckiner I, Keser S, Bayar A, et al. Successful repair of a bladder herniation after old traumatic pubic symphysis diastasis using bone graft and hernia mesh. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2007;127:655–657. doi: 10.1007/s00402-007-0290-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]