Editor,

Congenital aniridia is caused by mutation of the PAX 6 gene, the so-called master gene in ocular development. Although cataract has been reported in several aniridia cohorts (Nelson et al. 1984; Sale et al. 2002; Hingorani & Moore 20082009; Abouzeid et al. 2009; Park et al. 2010; He et al. 2012), the timing and detailed phenotype of cataract in aniridia have not been well described. Here, we report the onset of cataract, timing of cataract surgery and phenotypic features of cataract in a Norwegian aniridia cohort.

A cohort of 26 Norwegian patients (52 eyes) with ngenital aniridia was examined on a single occasion, after obtaining written informed consent and ethical approval from the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics, Oslo. Medical records were examined to detail cataract presence and surgical intervention. Digital slit lamp photographs of the lens and visual assessment were used to analyse the type and development of cataract, and aniridia-associated keratopathy (AAK) was characterized according to our previously published grading scale (Edén et al. 2012).

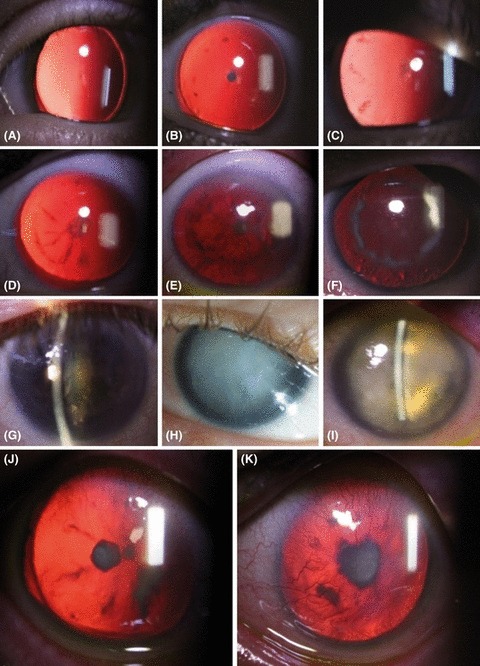

Mean patient age was 29 years (range: 4–63 years). Only three eyes were phakic with clear lenses; the remaining eyes had either cataract or had been operated on for cataract. The youngest individual with cataract was 4 years old at examination, but congenital or early onset cataract was documented in medical records of five patients (six eyes). Of 12 patients with nonoperated cataract, five (nine eyes) had lens luxation upwards. Of 14 patients, 27 eyes had glaucoma. Those least affected presented with a discrete posterior polar cataract. In other cases, a discrete subcapsular opacification of varying density or opacification extending radially from the mid-periphery of the posterior capsule was found in addition to the polar cataract. A posterior subcapsular mid-peripheral ring of opacification was observed, in some also combined with a more substantial polar cataract. The size and density of the opaque ring varied (Fig. 1). Findings in other patients included nuclear cataract (both turbid and yellow-brownish), one generalized subcapsular oedema (mature cataract) and one with a dehydrated opaque lens (hypermature cataract) (Fig. 1). In two patients, an anterior polar cataract was identified one of which had an additional posterior subcapsular opacification (Fig. 1).

Fig 1.

Developmental patterns of cataract in aniridia patients. (A) Early stage discrete posterior subcapsular cataract. (B–E) The posterior subcapsular cataract is denser. A posterior subcapsular opacification develops on the capsule in the mid-periphery as tiny flecks (B), or short, radially oriented opacities (C). (D–F) Radial opacities extend towards to posterior pole, and a mid-peripheral ring of opacification of varying density is present. Opacification always remained subcapsular. Late lens changes included yellow and turbid nuclear cataract (G), mature cataract (H) and hypermature cataract (I). (J) Anterior polar cataract in combination with a posterior polar cataract in one patient. (K) One patient presented with anterior polar cataract only.

Of the 52 eyes examined, 25 had had surgical intervention (cataract, glaucoma or both). Nine patients (13 eyes) had cataract surgery only, six patients (eight eyes) both cataract and glaucoma surgery and three patients (four eyes) glaucoma surgery only. At the time of cataract surgery, 7 of 12 operated patients were under the age of 19 years and 4 of these were under the age of 10. Secondary cataract was observed in four patients (six eyes).Of the 25 eyes with surgical intervention, eight eyes (30%) had AAK affecting visual acuity compared to 8/25 eyes (32%) in the group of eyes without intraocular surgery. No clear trend could be found towards an increased prevalence of AAK in operated eyes.

Cataract is common in aniridia, with over 90% prevalence in our cohort, similar to a Korean cohort with 60 eyes where 88% had cataract or were operated for cataract (Park et al. 2010). Cataract prevalence in aniridia in the literature varies from 50 to 85% (Nelson et al. 1984).

Patients in our cohort not operated for cataract showed a distribution of lens opacities that could be interpreted as a pattern of cataract development. A discrete posterior polar opacity seems to emerge first. The posterior location of polar opacities has been reported previously (Yamn et al. 2011; Jin et al. 2012). The next phase is an additional subcapsular opacification in the mid-periphery. These opacities then increase in density and size, radiate to the polar region and are always limited to the posterior subcapsular region. They eventually form a ring on the posterior capsule.

References

- Abouzeid H, Youssef MA, El Shakankiri N, Hauser P, Munier FL, Schorderet DF. PAX6 aniridia and interhemispheric brain anomalies. Mol Vis. 2009;15:2074–2083. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edén U, Fagerholm P, Danyali R, Lagali N. Pathologic epithelial and anterior corneal nerve morphology in early-stage congenital aniridic keratopathy. Ophthalmology. 2012;119:1803–1810. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2012.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Y, Pan Z, Luo F. A novel PAX 6 mutation in Chinese patients with severe congenital aniridia. Curr Eye Res. 2012;37:879–883. doi: 10.3109/02713683.2012.688165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingorani M, Williamson KA, Moore AT, Van Heyningen V. Detailed ophthalmologic evaluation of 43 individuals with PAX6 mutations. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:2581–2590. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin C, Wang Q, Li J, Zhu Y, Shentu X, Yao K. A recurrent PAX6 mutation is associated with aniridia and congenital progressive cataract in a Chinese family. Mol Vis. 2012;18:465–470. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson LB, Spaeth GL, Nowinski TS, Margo CE, Jackson L. Aniridia. A review. Surv Ophthalmol. 1984;28:621–642. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(84)90184-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park SH, Park YG, Lee MY, Kim MS. Clinical features of Korean patients with congenital aniridia. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2010;24:291–296. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2010.24.5.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sale MM, Craig JE, Charlesworth JC, et al. Broad phenotypic variability in a single pedigree with a novel 1410delC mutation in the PST domain of the PAX 6 gene. Hum Mutat. 2002;20:322. doi: 10.1002/humu.9066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamn N, Zhao Y, Wang Y, Xie A, Huang H, Yu W, Liu X, Cai S-P. Molecular genetics of familial nystagmus complicated with cataract and iris anomalies. Mol Vis. 2011;17:2612–2617. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]