Abstract

Background

Atopic diseases are more prevalent in industrialized countries than in developing countries. In addition, significant differences in the prevalence of allergic diseases are observed between rural and urban areas within the same country. This difference in prevalence has been attributed to what is called the ‘hygiene hypothesis’. Although parasitic infections are known to protect against allergic reactions, the mechanism is still unknown. The aim of this study was to investigate whether or not malarial infections can inhibit atopic dermatitis (AD)-like skin lesions in a mouse model of AD.

Methods

We used NC/Nga mice which are a model for AD. The NC/Nga mice were intraperitoneally infected with 1 × 105 Plasmoduim berghei (Pb) XAT-infected erythrocytes.

Results

Malarial infections ameliorated AD-like skin lesions in the NC/Nga mice. This improvement was blocked by the administration of anti-asialo GM1 antibodies, which are anti-natural killer (NK) cells. Additionally, adoptive transfer of NK cells markedly improved AD-like skin lesions in conventional NC/Nga mice; these suggest that the novel protective mechanism associated with malaria parasitic infections is at least, in part, dependent on NK cells.

Conclusions

We have experimentally demonstrated for the first time that malarial infections ameliorated AD-like skin lesions in a mouse model of AD. Our study could explain in part the mechanism of the ‘hygiene hypothesis’, which states that parasitic infections can inhibit the development of allergic diseases.

Keywords: atopic dermatitis, E4 promotor-binding protein 4, hygiene hypothesis, natural killer cells, Plasmodium berghei

A significant increase in the prevalence of allergic diseases such as asthma, allergic rhinitis, and atopic dermatitis (AD) has been observed over the past several decades (1). In particular, atopic diseases have become more prevalent in industrialized countries than in developing countries (2). It has also been recognized that parasitic infections suppress allergic diseases (3). For example, areas endemic for helminth infections have a low prevalence of allergic diseases (4). In addition, significant differences in the prevalence of allergic diseases have been noted between rural and urban areas within the same country (5). This epidemiological research could infer that bacterial, viral, and/or parasitic infections in early childhood may reduce the risk of allergy (6). One possible explanation, the ‘hygiene hypothesis’, has proposed that a lack of early childhood exposure to infectious agents can lead to a higher incidence of allergic disorders (7). Symbiotic microorganisms (e.g., gut flora or probiotic bacterium) and parasites prevent the symptoms of allergic diseases (8, 9). For example, helminth infections stimulate strong T helper 2 (Th2) responses and IgE production (2). The proposed mechanism may be that helminth infections induce polyclonal nonspecific IgE antibodies capable of blocking allergic hypersensitivity (10). In another study, researchers found that a helminth infection induces interleukin-10 (IL-10) from T cells and lowers the risk of skin hyper-reactivity to allergens (11). Collectively, parasitic infections may reduce the production of Th2 cytokines that are associated with allergy. Furthermore, polarized Th2 immune responses play a critical role in the skin inflammation in AD (12).

Malaria, caused by the protozoan parasites of the genus plasmodium, is still a life-threatening infectious disease. Two hundred million people are infected annually with malaria parasites (13). Malaria infection exerts significant suppressive effects on the host immune system to evade the host's defenses (14). A recent study demonstrated that activated regulatory T cells contribute to immune suppression during a malaria infection through the Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9) (15, 16). In other reports, researchers found that IL-10 and natural killer (NK) cells were required for the host immune system to avoid hepatic pathology or cerebral malaria (17). Immunomodulation through experimental parasitic infection has also been reported. For example, some patients with Crohn's disease achieved remission after a single oral dose of Trichuris suis eggs (18).

There have been no published data on immunomodulation by malarial infection in AD animal models. The aim of this study was to investigate whether or not malarial infections can inhibit AD-like skin lesions in the NC/Nga mouse model.

Materials and methods

For additional information about the used methods, we refer to the Supporting Information section.

Mice and parasites

NC/Nga mice have been considered as a suitable animal model for AD (19). SPF NC/Nga male mice were between 10 and 12 weeks old were purchased from Japan SLC, Inc. (Shizuoka, Japan) and kept in an SPF environment. Age- and sex-matched groups of conventional NC/Nga male mice were separately purchased from Japan SLC and maintained separately under conventional conditions or SPF conditions.

Plasmoduim berghei XAT (Pb XAT) is an irradiation-induced attenuated variant obtained from the lethal Pb NK65 strain. Blood-stage Pb XAT parasites were used in all experiments (20).

Determination of parasitemia

Blood samples were collected from the tail vein of the infected mice. The percentage of parasitized erythrocytes (i.e., parasitemia) out of the total number of erythrocytes was calculated.

Dermatitis evaluation

The clinical skin severity score of dermatitis was assessed for 4 symptoms: erythema/hemorrhage, scaling/dryness, edema, and excoriation/erosion (21).

Immunohistochemistry

The back skin of the mice was collected under anesthesia. The sections were stained with H&E and several primary antibodies.

Real-time quantitative PCR

Total RNA was extracted from the spleen and skin, respectively. Using an ABI PRISM 7700 instrument (Applied Biosystems, Foster, CA, USA), real-time PCR was performed by TaqMan gene expression assays.

Measurements of total IgE and parasite-specific IgE

Total IgE and parasite-specific IgE levels were measured by a sandwich ELISA method using the mouse IgE ELISA Quantitation Set (Bethyl Laboratories, Inc., Montgomery, TX, USA).

Administration of anti-NK cells

The mice were injected intraperitoneally with 100 μl of PBS solution containing 100 μg of anti-asialo GM1 antibodies (Wako, Osaka, Japan) every other day. In the control group, the mice were injected intraperitoneally with the same concentration of normal rabbit serum every other day. The spleen cells and peripheral blood cells were stained and analyzed using FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), and the list data were analyzed using Flowjo Software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR, USA).

Adoptive transfer of NK cells

A total of 1.0 × 106 NK cells from Pb XAT-infected mice were transferred intravenously per mouse. In the control group, PBS or adoptive transfer of the cells except NK cells were injected intravenously.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analyses of the experimental data were performed using one-way anova and Tukey's test using SPSS Statistics. Results were expressed as mean ± SD. P < 0.05 was accepted as significant.

Results

The SPF NC/Nga mice were divided into two groups: one group of mice was kept under SPF conditions without Pb XAT infection (SPF-uninfected mice), and another group was kept under SPF conditions and infected with Pb XAT (SPF Pb XAT mice). The NC/Nga mice kept under conventional conditions were also divided into two groups as described above (conventional uninfected mice and conventional Pb XAT mice).

Parasitemia and clinical skin severity score

Under both SPF and conventional conditions, the NC/Nga mice that were infected with Pb XAT developed parasitemia within 2 weeks and maintained high levels of parasitemia at 4 weeks. Most mice were spontaneously cured from parasitemia at 4–6 weeks. No difference was observed between the infection period and the parasitemia level in the both groups (Fig. S1).

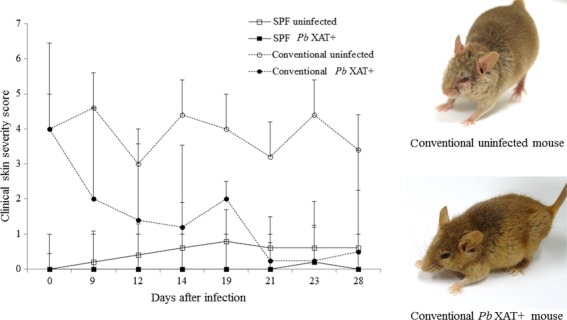

The clinical skin severity score started to decline in the conventional Pb XAT mice 1 week after the Pb XAT infection and reached a plateau at 3 weeks (Fig. 1). Accordingly, the clinical skin severity score was inversely correlated with parasitemia (Fig. S2). In contrast, the clinical skin severity score of the conventional uninfected NC/Nga mice remained high. AD-like dermatitis did not develop in both the SPF-uninfected and Pb XAT mice (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

The clinical skin severity score of the AD-like skin lesions. Conventional condition NC/Nga mice (○; uninfected, •; Plasmoduim berghei, Pb XAT infected); clinical skin severity score tended to decrease with Pb XAT infections in the conventional condition NC/Nga mice. SPF condition NC/Nga mice did not develop any AD-like skin lesions after Pb XAT infection (□; uninfected, ▪; Pb XAT infected).

Histological features of skin lesions

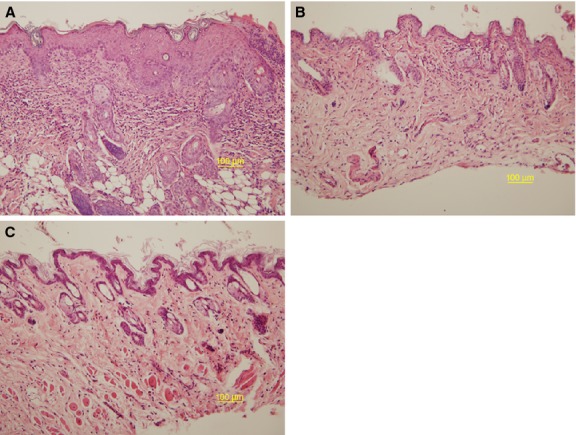

Typical histological features of AD were observed in the dorsal skin of the conventional uninfected mice, such as hyperkeratosis, elongation of rete ridges, intercellular edema, and an increased number of infiltrating mononuclear cells in the dermis. However, the dorsal skin lesions showed a decreased number of mononuclear cells in the dermis 2 weeks after Pb XAT infection in the conventional Pb XAT mice (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

(A–C) Histological features of the skin lesions from NC/Nga mice. The sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (×200). (A) Conventional condition mice; hyperkeratosis, spongiosis, and acanthosis in the epidermis with perivascular mononuclear cell infiltrations in the dermis. (B) Conventional condition mice 2 weeks after Plasmoduim berghei (Pb) XAT infection; a decreased number of mononuclear cells infiltrated the dermis (C) SPF condition mice.

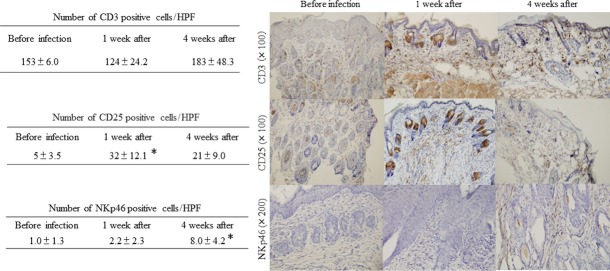

In the immunohistochemical study, the conventional condition mice revealed that the number of CD3-positive cells was not significantly changed after infection. A small number of NKp46- and CD25-positive cells were detected in the conventional condition mice before infection. CD25-positive cells slightly increased during the early stages of infection, and NKp46-positive cells increased gradually during infection (Fig. 3). On the other hand, NKp46-positive cells were not detected without infection in SPF mice.

Figure 3.

Immunohistochemical staining of the skin lesions from NC/Nga mice. The sections were stained with CD3, CD25, and NKp46. CD3-positive cells did not increase after Pb XAT infection. A small number of CD25 and NKp46 cells were detected in the conventional NC/Nga mice before infection. CD25-positive cells in the skin lesions slightly increased during the early stages of infection. NKp46-positive cells increased gradually during infection. *P < 0.05.

Expression of mRNA in splenocytes and skin

The balance of T-cell-derived cytokines is skewed to the Th2 type during the acute phase of human AD. First, we measured serum levels of interferon (IFN)-γ, IL-4, -5, and -10. However, these cytokines could not be detected both in the sera of conventional and SPF mice, irrespective of malarial infection. Therefore, we analyzed the cytokine production in cultured spleen mononuclear cells.

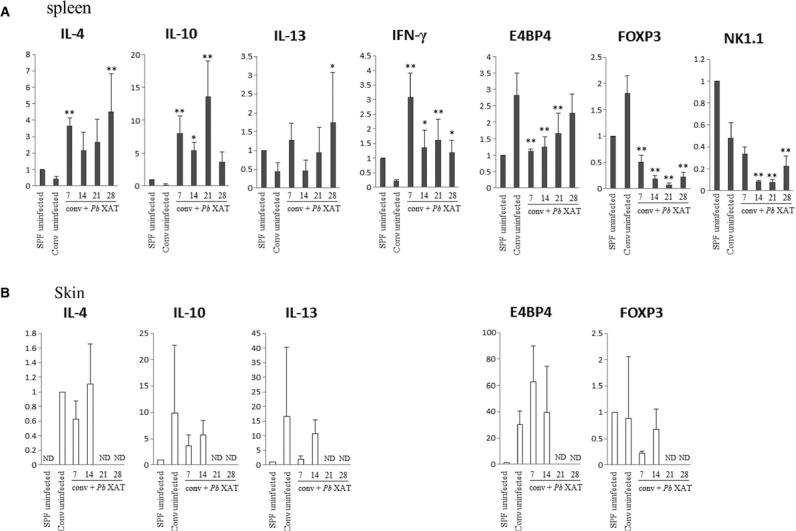

The secretion of IFN-γ and IL-10 by splenocytes increased during the early stages of infection, but IL-4 was not detected (data not shown). These findings were consistent with previous reports (22, 23). Next, we compared the levels of mRNA of several cytokines in spleen cells (Fig. 4). The expression of IL-4, -10, -13, and IFN-γ mRNA was increased in the early stages of infection in both groups of mice when compared with the SPF-uninfected mice and conventional uninfected mice. In contrast, the expression of forkhead box P3 (FOXP3), E4 promotor-binding protein 4 (E4BP4), and NK1.1 decreased at least for 3 weeks. In the skin, the expression of IL-4, -10, and -13 mRNA did not show significant changes. FOXP3 expression did not decrease, but E4BP4 increased markedly, but not significantly. NK1.1 and IFN-γ were not detected in the skin samples (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

The expression of IL-4, IL-10, IL-13, IFN-γ, NK1.1, E4 promotor-binding protein 4 (E4BP4), and FOXP3 mRNA in the spleen (A) and skin (B) from NC/Nga mice. Real-time RT-PCR was utilized to evaluate the expression levels of IL-4, IL-10, IL-13, IFN-γ, NK1.1, E4BP4, and FOXP3 mRNA in the spleen from the conventional condition Plasmoduim berghei (Pb) XAT NC/Nga mice and the conventional uninfected NC/Nga mice. The levels of mRNA are presented relative to the gene expression of GAPDH and are shown by comparing the data of the SPF-uninfected mice. Data are mean ± SD of three different mice. The expression of IL-4, IL-10, IL-13, and IFN-γ mRNA in the spleen was increased at the early stages of infection. In contrast, the expression of NK1.1, E4BP4, and FOXP3 decreased. The expression of mRNA in the skin showed results opposite to that of the spleen. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

IgE production

Many patients with AD reveal increased levels of serum IgE. We measured the serum IgE levels in the conventional uninfected, SPF-uninfected, conventional Pb XAT, and SPF Pb XAT NC/Nga mice, respectively. The increase of serum IgE levels in conventional NC/Nga mice was still present after infection with Pb XAT even after the skin lesions were ameliorated (Fig. S3A). As shown in Fig. S3B, the levels of Plasmodium antigen-specific IgE slightly, but not remarkably, increased on 28 days after infection in conventional NC/Nga mice. In the SPF condition mice, serum IgE levels were not increased with or without Pb XAT infection.

Decrement of NK cells

To deplete NK cells, mice were injected intraperitoneally with anti-asialo GM1 antibody. Administration of the antibodies resulted in a decrease in the NK cells from the peripheral blood of the NC/Nga mice. The conventional uninfected mice revealed fewer NK cells than the SPF-uninfected mice (5.3 ± 2.9% and 10.2 ± 2.5%, respectively). In addition, the percentage of NK cells increased after Pb XAT infection only in the conventional condition mice, but decreased in the SPF condition mice after infection. Anti-asialo GM1 antibodies were more effective in NK cell depletion in the SPF condition mice than in the conventional condition mice (Fig. 5). The skin lesions also did not improve in the conventional Pb XAT mice that received anti-asialo GM1 antibodies (Fig. 6). In the SPF-uninfected mice, the administration of anti-asialo GM1 antibodies did not lead to any skin lesions.

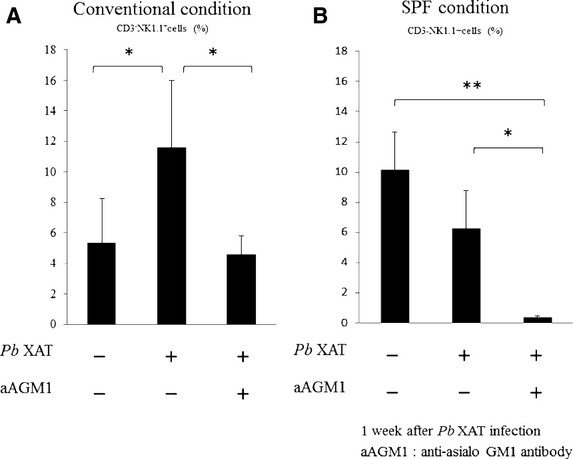

Figure 5.

Percentage of CD3−NK1.1+ cells in total mononuclear cells of peripheral blood in the conventional condition mice (A) and the SPF condition mice (B) 1 week after Plasmoduim berghei (Pb) XAT infection. The conventional uninfected mice revealed fewer NK cells than the SPF-uninfected mice (5.3 ± 2.9% and 10.2 ± 2.5%, respectively). (A) CD3−NK1.1+ cells in peripheral blood increase 1 week after Pb XAT infection in the conventional mice. In contrast, in the anti-asialo GM1-treated mice, CD3-NK1.1+ cells decrease similar to uninfected mice, despite Pb XAT infection. n = 3–6/group *P < 0.05. (B) In the SPF condition mice, NK cells tended to decrease after Pb XAT infection. n = 3–6/group *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Anti-asialo GM1 antibodies have more effect on the SPF condition mice than on the conventional condition mice.

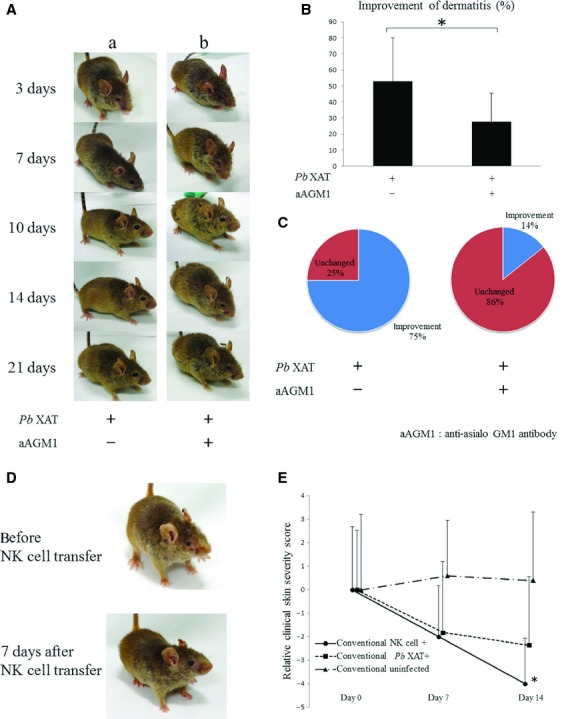

Figure 6.

Comparison of the clinical skin severity score between the conventional Plasmoduim berghei (Pb) XAT NC/Nga mice in addition to the anti-asialo GM1 treatment or adoptive transfer of NK cells n = 5–9/group *P < 0.05. (A) Representative clinical observations of atopic dermatitis-like skin lesions in (A-a) Pb XAT-infected conventional NC/Nga mice and (A-b) Pb XAT-infected conventional NC/Nga mice treated with anti-asialo GM1 antibodies to deplete NK cells. Only Pb XAT infection ameliorated the atopic dermatitis-like skin lesions in 2 or 3 weeks. In contrast, administration of anti-asialo GM1 antibodies was less likely to improve dermatitis similar to the conventional infected mice. (B, C) Improvement of dermatitis in mice treated with anti-asialo GM1 antibodies was significantly reduced compared with the untreated infected mice (3 weeks after infection). (D) Representative clinical observations of NK cell transfer in conventional condition NC/Nga mice. (E) The relative clinical skin severity score of the AD-like skin lesions. Conventional condition NC/Nga mice (•; NK cell transfer, ▪; Pb XAT infected, ▴; uninfected); clinical skin severity score decreased in NK cell transfer experiment as same as Pb XAT infection. 4/group *P < 0.05 compared with conventional condition uninfected mice.

Adoptive transfer of NK cells

As shown in Fig. 6D,E, adoptive transfer of NK cells markedly improved atopic dermatitis-like skin lesions in conventional NC/Nga mice in a week. On the other hand, in the control group, PBS treatment or adoptive transfer of the cells except NK cells did not improve the skin lesions.

Discussion

Atopic dermatitis is a pruritic and chronic inflammatory skin disease associated with a genetic background of atopic diathesis (24, 25). Atopic dermatitis develops as consequence of a complex interaction of genetic, immunological, and environmental factors (26). There have been many studies focusing on AD, primarily to investigate the immunological aspects of the disease and the role of the barrier function. It is still unclear whether parasitic infections can suppress AD, and if so, it is important to investigate the actual mechanism.

We demonstrated that NC/Nga mice infected with Pb XAT showed improvement in their AD-like skin lesions. As shown in Figs 1 and 2, parasitemia and AD-like skin lesions were inversely correlated, suggesting that malarial infections improved the skin lesions. The expression of IL-4, -10, -13, and IFN-γ mRNA in the spleen cells was increased during the early stages of malarial infection. In addition, immunohistochemical staining of the skin showed an increased number of NKp46-positive cells. The number of CD25-positive cells also tended to increase during the early stages of infection, but the number of CD3-positive cells was unchanged before and after infection. On the basis of our findings in this study, we infer that NK cells may contribute to the improvement of dermatitis in NC/Nga mice during malarial infections. As shown in Fig. 5, a remarkable increase in IFN-γ was observed in the early stages of infection. This result is consistent with a previous report (22). Also, the expression of NK1.1 and IFN-γ mRNA was reduced in the conventional uninfected mice compared with the SPF-uninfected mice. We demonstrated that the depletion of NK cells did not improve the dermatitis even during malarial infection. In contrast, in the SPF-uninfected mice, the depletion of NK cells did not cause dermatitis. Additionally, adoptive transfer of NK cells markedly improved atopic dermatitis-like skin lesions in conventional uninfected NC/Nga mice. Based on these results, we conclude that NK cells play an important role in the improvement of dermatitis in malarial infections.

In humans, it has also been reported that the number of circulating NK cells and IFN-γ production by NK cells at the single-cell level was reduced in AD (27). This change may skew immune responses toward a Th2 pattern and contribute to a susceptibility to infection in AD. It is well known that NK cells play an important role in both innate and adaptive immunity. NK cells produce cytokines that influence Th-cell polarization, and activated NK cells stimulate B cells to secrete immunoglobulins. It has been shown that human NK cells are able to polarize in vitro into two functionally different subsets, NK1 and NK2, which are analogous to the T-cell subsets Th1 and Th2. NK1 cells produce IFN-γ and inhibit IgE production while NK2 cells produce IL-5 and IL-13 and stimulate IgE production (28). In addition, NK regulatory cells are another subset of NK cells. NK regulatory cells that secrete IL-10 and TGF-β play major roles in immune regulation in the context of viral infection and promote transplant and pregnancy tolerance (29). In AD, it is well established that the imbalance of Th1/Th2 T-cell polarization and the bias toward Th2 cytokine production plays a pivotal role in both the initiation and maintenance of these events. In addition, patients with allergic diseases have abnormalities of immune regulation associated with NK cells. These facts and our experimental results indicate that malaria infection causes an increase in the overall numbers of NK cells, the differentiation into NK1 cells, and the increase in NK regulatory cells.

Alternatively, the chemokine receptor CXCR3 may support the improvement of dermatitis due to malaria infection. CXCR3 is preferentially expressed in NK cells (30). It is known that CXCR3 significantly increases during malaria infection (31). In contrast, patients with severe AD often have a reduced frequency of CXCR3+ cells (32, 33). Therefore, it may be possible to compensate for the reduced expression of CXCR3 associated with AD using malarial infection; this fact may be strongly related to NK cells.

E4 promotor-binding protein 4, a basic leucine zipper transcription factor, is a critical regulator of NK cell development through its induction of the transcriptional inhibitor Id2; it also regulates IgE class switching in B cells. In the immune system, E4BP4 is known as NFIL-3, as it regulates the IL-3 promoter and promotes IL-3-mediated cell survival (34, 35). In our study, the expression of E4BP4 mRNA in the spleen decreased during the early stages of infection and eventually returned to almost the same levels of the conventional uninfected mice (Fig. 4). Inversely, the expression of E4BP4 mRNA in the skin increased in the early stages of infection and decreased 3–4 weeks after infection (Fig. 4). We speculate that immature NK cells are mobilized from the spleen to other organs and then differentiate into mature NK cells. We also believe that malarial infections enhance the expression of E4BP4 and cause an increase of NK cells in AD skin lesions.

Collectively, for the first time, we demonstrate that parasitic infection inhibits AD-like skin lesions in a mouse model of AD. Our data showed that the number of NK cells in the skin increased after malarial infection possibly via upregulation of E4BP4. This understanding of the ‘hygiene hypothesis’ will open a new era of AD research.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Prof. John Bienenstock (McMaster University, Ontario, Canada) for the prereview of the manuscript. We would like to thank Prof. M. Kubo (RIKEN, Kanagawa, Japan) for helpful suggestions of E4BP4. We would like to thank Dr. H. Akiyama (NIHS, Tokyo, Japan) for helpful discussion, suggestions throughout this work.

Author contributions

CK, HA, KS, and OI contributed to conception and design. CK, HA, and KS performed research; CK, HA, KS, and OI analyzed data. CK, HA, KS, and OI wrote the paper. All authors approved this version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article:

Time course of malaria parasitemia in SPF NC/Nga and conventional NC/Nga mice.

Relationship between the clinical skin severity score and parasitemia in the conventional condition NC/Nga mice.

(A, B) Serum levels of IgE and parasite-specific IgE in the NC/Nga mice kept under SPF and conventional conditions with/without Pb XAT infection.

Materials and methods.

References

- 1.Sears MR. Epidemiology of childhood asthma. Lancet. 1997;350:1015–1020. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)01468-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Study TI, Committee S. Worldwide variation in prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and atopic eczema: ISAAC. Lancet. 1998;351:1225–1232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carswell F, Meakins RH, Harland PS. Parasites and asthma in Tanzanian children. Lancet. 1976;2:706–707. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(76)90004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lynch NR, Hagel I, Perez M, Di Prisco MC, Lopez R, Alvarez N. Effect of anthelmintic treatment on the allergic reactivity of children in a tropical slum. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1993;92:404–411. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(93)90119-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Renz H, Von Mutius E, Illi S, Wolkers F, Hirsch T, Weiland SK. T(H)1/T(H)2 immune response profiles differ between atopic children in eastern and western Germany. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;109:338–342. doi: 10.1067/mai.2002.121459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gereda JE, Leung DY, Thatayatikom A, Streib JE, Price MR, Klinnert MD, et al. Relation between house-dust endotoxin exposure, type 1 T-cell development, and allergen sensitisation in infants at high risk of asthma. Lancet. 2000;355:1680–1683. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02239-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Strachan DP. Hay fever, hygiene, and household size. Br Med J. 1989;299:1259–1260. doi: 10.1136/bmj.299.6710.1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tanaka A, Jung K, Benyacoub J, Prioult G, Okamoto N, Ohmori K, et al. Oral supplementation with Lactobacillus rhamnosus CGMCC 1.3724 prevents development of atopic dermatitis in NC/NgaTnd mice possibly by modulating local production of IFN-gamma. Exp Dermatol. 2009;18:1022–1027. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0625.2009.00895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lau S, Gerhold K, Zimmermann K, Ockeloen CW, Rossberg S, Wagner P, et al. Oral application of bacterial lysate in infancy decreases the risk of atopic dermatitis in children with 1 atopic parent in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129:1040–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hagel I, Lynch NR, Pérez M, Prisco MCDI, López R, Rojas E. Modulation of the allergic reactivity of slum children by helminthic infection. Parasite Immunol. 1993;15:311–315. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1993.tb00615.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van den Biggelaar AH, van Ree R, Rodrigues LC, Lell B, Deelder AM, Kremsner PG, et al. Decreased atopy in children infected with Schistosoma haematobium: a role for parasite-induced interleukin-10. Lancet. 2000;356:1723–1727. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)03206-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guttman-Yassky E, Nograles KE, Krueger JG. Contrasting pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis and psoriasis–part I: clinical and pathologic concepts. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:1110–1118. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.01.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.White NJ, Pukrittayakamee S, Hien TT, Faiz MA, Mokuolu OA, Dondorp AM. Malaria. Lancet. 2014;383:723–735. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60024-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Good MF, Kaslow DC, Miller LH. Pathways and strategies for developing a malaria blood-stage vaccine*. Annu Rev Immunol. 1998;16:57–87. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.16.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hisaeda H, Maekawa Y, Iwakawa D, Okada H, Himeno K, Kishihara K, et al. Escape of malaria parasites from host immunity requires CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells. Nat Med. 2004;10:29–30. doi: 10.1038/nm975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hisaeda H, Tetsutani K, Imai T, Moriya C, Tu L, Hamano S, et al. Malaria parasites require TLR9 signaling for immune evasion by activating regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2008;180:2496–2503. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hansen DS, Bernard NJ, Nie CQ, Schofield L. NK cells stimulate recruitment of CXCR3+ T cells to the brain during Plasmodium berghei-mediated cerebral malaria. J Immunol. 2007;178:5779–5788. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.9.5779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Summers RW, Elliott DE, Qadir K, Urban JF, Thompson R, Weinstock JV. Trichuris suis seems to be safe and possibly effective in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2034–2041. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07660.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsuda H, Watanabe N, Geba GP, Sperl J, Tsudzuki M, Hiroi J, et al. Development of atopic dermatitis-like skin lesion with IgE hyperproduction in NC/Nga mice. Int Immunol. 1997;9:461–466. doi: 10.1093/intimm/9.3.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Suzuki M, Waki S, Igarashi I, Tamura J, Imanaka M, Ishikawa S. Host responses induced in mice by a radiation-attenuated Plasmodium berghei (NK65) malaria parasite. Int J Nucl Med Biol. 1980;7:141–148. doi: 10.1016/0047-0740(80)90032-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leung DY, Hirsch RL, Schneider L, Moody C, Takaoka R, Li SH, et al. Thymopentin therapy reduces the clinical severity of atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1990;85:927–933. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(90)90079-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dogruman-Al F, Fidan I, Kustimur S, Ceber K, Imir T. Determination of the expression of lymphocyte surface markers and cytokine levels in a mouse model of Plasmodium berghei. New Microbiol. 2009;32:285–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Habu Y, Seki S, Takayama E, Ohkawa T, Koike Y, Ami K, et al. The mechanism of a defective IFN-gamma response to bacterial toxins in an atopic dermatitis model, NC/Nga mice, and the therapeutic effect of IFN-gamma, IL-12, or IL-18 on dermatitis. J Immunol. 2001;166:5439–5447. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.9.5439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bieber T, Cork M, Reitamo S. Atopic dermatitis: a candidate for disease-modifying strategy. Allergy. 2012;67:969–975. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2012.02845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boguniewicz M, Leung DYM. Recent insights into atopic dermatitis and implications for management of infectious complications. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:4–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Amano H, Negishi I, Akiyama H, Ishikawa O. Psychological stress can trigger atopic dermatitis in NC/Nga mice: an inhibitory effect of corticotropin-releasing factor. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:566–573. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Katsuta M, Takigawa Y, Kimishima M, Inaoka M, Takahashi R, Shiohara T. NK cells and gamma delta+ T cells are phenotypically and functionally defective due to preferential apoptosis in patients with atopic dermatitis. J Immunol. 2006;176:7736–7744. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.12.7736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aktas E, Akdis M, Bilgic S, Disch R, Falk CS, Blaser K, et al. Different natural killer (NK) receptor expression and immunoglobulin E (IgE) regulation by NK1 and NK2 cells. Clin Exp Immunol. 2005;140:301–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2005.02777.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deniz G, van de Veen W, Akdis M. Natural killer cells in patients with allergic diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;132:527–535. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bonecchi R, Bianchi G, Bordignon PP, D'Ambrosio D, Lang R, Borsatti A, et al. Differential expression of chemokine receptors and chemotactic responsiveness of type 1 T helper cells (Th1s) and Th2s. J Exp Med. 1998;187:129–134. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.1.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hansen DS, Evans KJ, D'Ombrain MC, Bernard NJ, Sexton AC, Buckingham L, et al. The natural killer complex regulates severe malarial pathogenesis and influences acquired immune responses to Plasmodium berghei ANKA. Infect Immun. 2005;73:2288–2297. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.4.2288-2297.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nakatani T, Kaburagi Y, Shimada Y, Inaoki M, Takehara K, Mukaida N, et al. CCR4 memory CD4+ T lymphocytes are increased in peripheral blood and lesional skin from patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;107:353–358. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.112601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Akkoc T, de Koning PJ, Rückert B, Barlan I, Akdis M, Akdis CA. Increased activation-induced cell death of high IFN-gamma-producing T(H)1 cells as a mechanism of T(H)2 predominance in atopic diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;121:652–658. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.12.1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gascoyne DM, Long E, Veiga-Fernandes H, de Boer J, Williams O, Seddon B, et al. The basic leucine zipper transcription factor E4BP4 is essential for natural killer cell development. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:1118–1124. doi: 10.1038/ni.1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Motomura Y, Kitamura H, Hijikata A, Matsunaga Y, Matsumoto K, Inoue H, et al. The transcription factor E4BP4 regulates the production of IL-10 and IL-13 in CD4+ T cells. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:450–459. doi: 10.1038/ni.2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Time course of malaria parasitemia in SPF NC/Nga and conventional NC/Nga mice.

Relationship between the clinical skin severity score and parasitemia in the conventional condition NC/Nga mice.

(A, B) Serum levels of IgE and parasite-specific IgE in the NC/Nga mice kept under SPF and conventional conditions with/without Pb XAT infection.

Materials and methods.