Abstract

“Black” pigment gallstones form in sterile gallbladder bile in the presence of excess bilirubin conjugates (“hyperbilirubinbilia”) from ineffective erythropoiesis, hemolysis, or induced enterohepatic cycling (EHC) of unconjugated bilirubin. Impaired gallbladder motility is a less well-studied risk factor. We evaluated the spontaneous occurrence of gallstones in adult germfree (GF) and conventionally housed specific pathogen-free (SPF) Swiss Webster (SW) mice. GF SW mice were more likely to have gallstones than SPF SW mice, with 75% and 23% prevalence, respectively. In GF SW mice, gallstones were observed predominately in heavier, older females. Gallbladders of GF SW mice were markedly enlarged, contained sterile black gallstones composed of calcium bilirubinate and <1% cholesterol, and had low-grade inflammation, edema, and epithelial hyperplasia. Hemograms were normal, but serum cholesterol was elevated in GF compared with SPF SW mice, and serum glucose levels were positively related to increasing age. Aged GF and SPF SW mice had deficits in gallbladder smooth muscle activity. In response to cholecystokinin (CCK), gallbladders of fasted GF SW mice showed impaired emptying (females: 29%; males: 1% emptying), whereas SPF SW females and males emptied 89% and 53% of volume, respectively. Bilirubin secretion rates of GF SW mice were not greater than SPF SW mice, repudiating an induced EHC. Gallstones likely developed in GF SW mice because of gallbladder hypomotility, enabled by features of GF physiology, including decreased intestinal CCK concentration and delayed intestinal transit, as well as an apparent genetic predisposition of the SW stock. GF SW mice may provide a valuable model to study gallbladder stasis as a cause of black pigment gallstones.

Keywords: black pigment gallstones, germfree mice, impaired gallbladder motility, cholecystokinin

gallstone disease affects more than 20 million people in the United States and results in more than 700,000 cholecystectomies annually (32, 45, 46). Although not widely studied, pigment gallstones are observed in a variety of clinical conditions, and may account for up to 20–25% of gallstones among patients that undergo cholecystectomy in the Western world (19, 37, 55). While “brown” pigment gallstones form in septic bile, “black” pigment gallstones develop classically in sterile bile with the critical risk factor of hyperbilirubinbilia, defined as biliary hypersecretion of bilirubin conjugates, due principally to chronic hemolysis secondary to multiple syndromes, or ineffective erythropoiesis as seen with vitamin B12 and folate deficiencies (38, 48, 54, 55). Hyperbilirubinemia may also occur with prolonged intestinal transit, antibiotic therapy, and ileal dysfunction from induced enterohepatic cycling (EHC) of unconjugated bilirubin (UCB), wherein UCB enters the enterohepatic circulation to be reconjugated and resecreted into bile (18, 53, 54, 55, 56).

A pathophysiological role for intestinal bacteria, or the lack thereof, in black pigment gallstone formation has not been well documented, but may involve altered intestinal mucosal barrier function and changes in intestinal bilirubin deconjugation and formation of urobilinoids, facilitating EHC of UCB (9, 47, 54, 55, 59). The Division of Comparative Medicine at M.I.T. maintains a germfree (GF) Swiss Webster (SW) breeding colony to facilitate embryo transfer rederivation of other lines of mice into a GF status, and periodically purchases conventionally housed specific pathogen-free (SPF) SW mice for controls in various research studies. SW mice are customarily used as an inexpensive outbred stock for biomedical research, transgenic technology, and as sentinel mice for monitoring infectious diseases in research colonies. Interestingly, necropsies of adult female and male GF SW mice from our colony revealed 100% prevalence of markedly enlarged gallbladders, with 75% containing gallstones morphologically consistent with black pigment gallstones of humans, whereas SPF SW mice demonstrated 23% gallstone prevalence and normal-sized gallbladders.

It is known that GF mice have delayed intestinal transit, with documented 2 times less cholecystokinin (CCK)-like immunoreactivity in the small intestine from rapid degradation of CCK, compared with normally colonized mice, and that CCK acts to promote propulsive activity of the intestine (30, 34, 35, 50, 57, 61). The slower intestinal transit observed in GF mice is reminiscent of the altered peristaltic function in humans and experimental animals with cholesterol gallstone disease (36, 37, 58, 61). Although dysfunction in gallbladder and small intestinal motility has been linked to cholesterol gallstone disease, little is known about how hypomotility of the gallbladder influences black pigment gallstone formation (36, 37, 58). Gallbladder dysfunction has been reported in conditions associated with the formation of black pigment gallstones, including liver cirrhosis, truncal vagotomy, and administration of total parenteral nutrition, and in conditions more often associated with cholesterol gallstones such as obesity and/or Type II diabetes (4, 36, 37, 49, 54, 58). With recognized delayed intestinal transit in GF mice and the indefinite association of black pigment gallstones with gallbladder dysfunction in humans, we postulated that GF SW mice may provide a unique, spontaneous animal model to investigate the role of the gut microbiota and impaired gallbladder motility in black pigment gallstone formation in humans.

In turn, we characterized gallstone disease in GF and SPF SW mice by demographic profiling, logistic regression analysis, various gallbladder bile and gallstone analyses, and gallbladder and liver histology. Mice were screened for hematopoietic abnormalities, and conjugated and unconjugated bilirubin levels in hepatic bile determined to rule out ineffective erythropoiesis or hemolysis, and induced EHC of UCB, respectively. The proposed mechanism of impaired gallbladder motility was probed by determination of fasting gallbladder volumes and bile pH, screening for metabolic abnormalities such as diabetes, and evaluation of calcium ion (Ca2+) activity of gallbladder smooth muscle and gallbladder responsiveness to exogenous CCK.

METHODS

Mice.

GF outbred Tac:SW mice were obtained from Taconic Farms (Germantown, NY) and maintained as a breeding colony in a facility accredited by the Association for the Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International. One hundred twenty-five female and 99 male GF SW mice were bred periodically and aged further for purposes of this study (age range: 5–22 mo; 10.7 ± 0.2 mo old) (Table 1). For comparison with GF SW mice, SPF mice representing the same outbred genetic stock but colonized with intestinal microbiota were evaluated. Seventy-five female and 53 male SPF SW mice were purchased from Taconic as retired breeders (age range: 8–15 mo; 10.1 ± 0.2 mo old) (Table 1). SPF SW mice were free of exogenous murine viruses, bacterial pathogens, and parasites, and animal use was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the collaborating institutions.

Table 1.

Demographic profile of germfree and specific pathogen-free Swiss Webster mice

| Age, mo |

Body Weight, g* |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microbial Status | n | Gallstone Prevalence | Mean ± SE | Range | Mean ± SE | Range |

| GF SW Mice | ||||||

| All | 224 | 75% | 10.7 ± 0.2 | 5–22 | 48.6 ± 0.6 | 28.6–75.6 |

| Gallstones | 169 | 11.1 ± 0.2 | 5–22 | 49.8 ± 0.7 | 31.3–75.6 | |

| No Gallstones | 55 | 9.7 ± 0.4 | 5–17 | 45.1 ± 1.1 | 28.6–63.8 | |

| Females | 125 | 84% | 11.0 ± 0.3 | 5–22 | 48.0 ± 0.8 | 28.6–75.6 |

| Males | 99 | 65% | 10.4 ± 0.3 | 5–17 | 49.3 ± 0.9 | 29.9–66.7 |

| SPF SW Mice | ||||||

| All | 128 | 23% | 10.1 ± 0.2 | 8–15 | 49.6 ± 0.8 | 28.6–86.8 |

| Gallstones | 30 | 10.2 ± 0.4 | 8–15 | 50.9 ± 1.3 | 40.0–68.6 | |

| No Gallstones | 98 | 10.1 ± 0.2 | 8–15 | 49.1 ± 0.9 | 28.6–86.8 | |

| Females | 75 | 20% | 10.5 ± 0.3 | 8–15 | 50.3 ± 1.1 | 28.6–86.8 |

| Males | 53 | 28% | 9.6 ± 0.3 | 8–14 | 48.6 ± 1.0 | 33.3–63.9 |

GF, germfree; SPF, specific pathogen-free; SW, Swiss Webster.

Eight body weight values not provided.

Husbandry.

GF SW mice were housed in sterile isolators in open-top polycarbonate cages on autoclaved hardwood bedding and fed autoclaved water and diet (Purina 5021, Purina Mills, St. Louis, MO) ad libitum. The diet had a guaranteed analysis of not less than 20% crude protein and 9% crude fat, and not more than 5% crude fiber and 6.5% ash. Macroenvironmental conditions included a 14:10 light/dark cycle and temperature maintenance at 68 ± 2°F. Weekly microbiologic monitoring of interior isolator surfaces, feed, water, and feces confirmed absence of all aerobic and anaerobic bacteria and fungi. SPF SW mice were housed in a barrier facility in standard, nonautoclaved microisolator cages under similar environmental conditions. To standardize nutrition, these mice were fed the same autoclaved diet for the duration of their lives. SPF status was monitored by a sentinel program.

Determination of gallbladder volume and bile pH.

Mice were euthanized by using carbon dioxide, and at necropsy relative gallbladder size and gross evidence of gallstones (relative size, approximate amount and color) were recorded.

Gallbladder volume (μl) and pH of gallbladder bile were determined for fasted GF (n = 6 females, 6 males; 12.0 ± 0.9 mo old) and SPF (n = 14 females, 15 males; 11.2 ± 0.6 mo old) SW mice. Mice were anesthetized by intraperitoneal injection of a cocktail of anesthetics in 9% NaCl, containing ketamine (80 mg/kg), xylazine (8 mg/kg), acepromazine (2 mg/kg), and atropine (0.012 mg/kg), and terminal cholecystectomies were performed as previously described (18). Following gallbladder removal, mice were euthanized by anesthetic overdose, followed by bilateral thoracotomy. Gallbladder bile was drained into tared 200-μl microcentrifuge tubes, and gallbladder volumes were quantified gravimetrically by equating weight and volume (i.e., 1 mg = 1 μl). Immediately afterward, gallbladder bile pH was measured by a micro pH electrode (Microelectrodes, Bedford, NH).

Gallbladder bile and gallstone analyses.

To characterize gallbladder bile sediment and gallstone morphology, fresh and previously frozen (−70°C) gallbladder bile samples from GF SW mice with (n = 5 females, 2 males; 16.9 ± 2.0 mo old) or without (n = 3 males; 10.3 ± 2.3 mo old) gross evidence of gallstones were evaluated microscopically under direct light. These samples from GF SW mice were compared with bile of 7 SPF SW mice (n = 3 females, 4 males; 10 mo old) lacking gross evidence of gallstones and one 15-mo-old SPF SW female mouse with gallstones, though the latter sample was kept at room temperature for an extended period of time prior to analysis. Additionally, fresh gallbladder tissue, bile, and gallstones from seven 11-mo-old GF SW female mice (n = 5 with gallstones) were examined by direct light and polarized light microscopy.

Gallstones from two 15-mo-old and two 22-mo-old GF SW females and one 15-mo-old GF SW male were sent to the Laboratory for Stone Research (Newton, MA) for compositional analysis by polarized light microscopy and infrared spectroscopy.

To determine cholesterol content of gallstones, microcentrifuge tubes containing gallstones in bile from 9-mo-old GF (n = 5 females, 4 males) and SPF (n = 3 females) SW mice were centrifuged for 15 min in a tabletop microcentrifuge (ISC BioExpress, Kaysville, UT). After bile supernatant was removed, gallstones were washed by vortexing thoroughly with 200 μl of 1% (wt/vol) Na tauroursodeoxycholate (NaTUDC). Then, samples from GF SW males and SPF SW females were pooled into one sample per group, whereas gallstones from female GF SW mice were combined into two samples. Samples were washed three more times with 200 μl of NaTUDC and then layered carefully onto a Nuclepore polycarbonate membrane filter (47 mm, 0.2 μm), washed with 5 ml of double distilled water, and filter dried under house vacuum. Filter residue was carefully scraped with the flat edge of a metal spatula and transferred to a tared aluminum weighing dish that had been dried under house vacuum at 60°C for 24 h. Dried gallstone samples were then resuspended in 150 μl of isopropanol. Clumps were broken gently with a glass stirring rod, and samples vortexed for 4 min and incubated at 37°C for 2 h in a shaking water bath. Immediately prior to analysis, 450 μl of acetonitrile was added to each sample. Gallstones were analyzed for cholesterol content by a modified HPLC method by using a Kinetex C18 column (2.6-μm particle size; Phenomenex, Torrance, CA) and eluting with acetonitrile-isopropanol (3:1, vol/vol) (52).

Gallstones from 12-mo-old GF (n = 3 females, 3 males; pooled into 1 sample) and SPF (n = 1 female) SW mice were also analyzed by electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy. Gallbladder bile supernatant was removed, and gallstones were washed 5 times with Chelex-treated water. The water was obtained from a Milli-Q purification system (18.2 mΩ/cm) and treated with Chelex resin (Bio-Rad, 10 g/l, stirred for >1 h and filtered) to remove contaminating metal ions prior to use. For washing, the gallstones were suspended in 180 μl of Milli-Q water in the sample reservoir of a centrifugal filter device, gently vortexed, and centrifuged (10,000 rpm × 5 min, 20°C). The washed gallstones remaining in the reservoir were resuspended in the Chelex-treated water (180 μl), transferred to acid-washed (2 M HCl) quartz EPR tubes and frozen in liquid nitrogen prior to analysis, and stored at −80°C. A sample of commercial bilirubin [98% (EmM/453 = 60); Sigma-Aldrich] was prepared in Chelex-treated Milli-Q water and frozen in liquid nitrogen prior to analysis. EPR spectra (X-band, 9 GHz) were recorded on a Bruker EMX spectrometer with an ER 4199HS cavity. An ESR900 cryostat outfitted with a Cernox sensor was employed for all measurements. Unless noted otherwise, the modulation amplitude and frequency was 1 mT at 100 kHz. Samples of twice-washed gallstones (4 samples pooled into 1 sample) and undiluted gallbladder bile (1 individual sample) from 14-mo-old female GF SW mice, as well as gallstones washed 5 times (4 samples pooled into 1 sample) from 15-mo-old GF SW mice were also analyzed.

Additional gallstones and gallbladder bile from GF (n = 2 females, 4 males; 12 mo old) and SPF (n = 3 females; 11 mo old) SW mice were aseptically collected for culture under aerobic and anaerobic (gas mix) conditions to confirm absence of gallbladder infection.

Screening for hematopoietic or metabolic abnormalities.

Following an overnight fast and carbon dioxide euthanasia, postmortem cardiac blood was collected for complete blood count (CBC) from 11 female and 12 male GF SW mice (10.8 ± 0.6 mo old), and 3 female and 3 male SPF SW mice (12 mo old), and for serum chemistry analysis from 11 female and 15 male GF SW mice (12.7 ± 1.1 mo old), and 4 female and 5 male SPF SW mice (10 mo old). CBCs were measured by using a Hemavet 950FS analyzer (Drew Scientific, Waterbury, CT) and serum was sent to IDEXX Laboratories (Memphis, TN) for a chemistry panel of 21 analytes [Table 5; 3 analytes (bicarbonate, creatine kinase, gamma-glutamyl transferase) excluded because of insufficient quantity for comparison].

Table 5.

Serum chemistry analytes from germfree and specific pathogen-free Swiss Webster mice

| GF SW Mice |

SPF SW Mice |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum Chemistry | Female, n = 11 | Male, n = 15 | Female, n = 4 | Male, n = 5 | Reference Values |

| Lipid and carbohydrate metabolism | |||||

| 2*Cholesterol, mg/dl | 221.5 ± 18.2 | 264.7 ± 14.9 | 150.3 ± 28.8 | 193.5 ± 32.1 | 114 ± 56 |

| 3a***Glucose, mg/dl | 226.0 ± 22.3 | 246.4 ± 16.4 | 207.7 ± 27.1 | 228.1 ± 32.0 | 112 ± 38 |

| Hepatic function | |||||

| Total bilirubin, mg/dl | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 0.4 ± 0.2 |

| Direct bilirubin, mg/dl | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | N/A |

| 3a*; 5a**Indirect bilirubin, mg/dl | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | N/A |

| Albumin, g/dl | 3.1 ± 0.1 | 3.1 ± 0.1 | 2.8 ± 0.2 | 2.8 ± 0.2 | N/A |

| Globulin, g/dl | 3.2 ± 0.2 | 3.3 ± 0.1 | 3.1 ± 0.3 | 3.3 ± 0.3 | N/A |

| Total protein, g/dl | 6.3 ± 0.2 | 6.5 ± 0.2 | 5.8 ± 0.3 | 6.0 ± 0.4 | 4.4 ± 1.1 |

| 2**Alanine aminotransferase, IU/l | 45.7 ± 9.0 | 35.4 ± 7.1 | 91.8 ± 14.0 | 81.5 ± 15.7 | 99 ± 86 |

| Alkaline phosphatase, IU/l | 85.3 ± 7.5 | 71.4 ± 5.9 | 59.2 ± 11.7 | 45.3 ± 13.1 | 39 ± 26 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase, IU/l | 143.8 ± 33.2 | 75.9 ± 27.0 | 133.1 ± 52.4 | 65.2 ± 58.5 | 196 ± 133 |

| Renal function | |||||

| 2*; 4a*Blood urea nitrogen, mg/dl | 17.4 ± 1.1 | 21.1 ± 0.9 | 21.5 ± 1.7 | 25.2 ± 1.9 | 38 ± 20 |

| Creatinine, mg/dl | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.0 | 1.1 ± 0.5 |

| Electrolytes, acid-base balance | |||||

| Calcium, mg/dl | 10.1 ± 0.2 | 10.1 ± 0.2 | 10.4 ± 0.3 | 10.4 ± 0.3 | 8.9 ± 2.1 |

| Chloride, meq/l | 108.9 ± 1.3 | 111.3 ± 1.0 | 104.9 ± 1.8 | 107.4 ± 2.0 | 125 ± 7.2 |

| 4b*Phosphorus, mg/dl | 8.6 ± 0.5 | 10.1 ± 0.4 | 8.5 ± 0.6 | 10.0 ± 0.7 | 8.3 ± 1.5 |

| Potassium, meq/l | 9.6 ± 0.7 | 10.2 ± 0.5 | 8.5 ± 1.0 | 9.1 ± 1.1 | 8.0 ± 0.9 |

| Sodium, meq/l | 154.1 ± 2.2 | 157.2 ± 1.6 | 152.4 ± 3.0 | 155.6 ± 3.3 | 166 ± 8.6 |

Statistically significant differences in analytes determined by ANCOVA are noted and relate to 1presence of gallstones, 2microbial status, 3age (direct relationship), 4sex or 5body weight (inverse relationship), with

GF and/or bSPF found responsible for significant effect(s) by ANCOVA stratified by microbial status;

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01,

P < 0.001. GF SW and SPF SW data represent adjusted mean ± standard error, where age and body weight are fixed at their means (n = 35; mean age: 12.0 mo; mean body wt: 43.6 g). Sixteen GF SW mice had gallstones, while no SPF SW mice analyzed had gallstones. Reference data for SW mice are not published, and reference values provided represent mean ± SD obtained from adult male CD-1 mice (21, 39, 40); N/A indicates no data available.

Because a predisposition to diabetes mellitus was previously reported for Tac:SW mice, GF and SPF SW mice were screened for glucosuria, fasting hyperglycemia (>300 mg/dl), and glucose intolerance (28, 39, 40), and pancreata were examined histologically. Naturally voided urine was collected in sterile polycarbonate caging or via postmortem cystocentesis from 11 female and 3 male GF SW mice (11.0 ± 0.7 mo old), and 5 female SPF SW mice (12 mo old). Clinical urinalysis dipsticks (Multistix 10 SG, Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, Tarrytown, NY) were used to measure protein, glucose, leukocytes, nitrites, ketones, bilirubin, blood, and urobilinogen. Specific gravity was measured when a sufficient urine volume was collected.

Glucose tolerance testing (GTT) was performed on 9-mo-old GF (n = 6 females, 5 males) and SPF (n = 6 females, 6 males) SW mice. Mice were fasted overnight, weighed, and baseline glucose was measured in blood obtained by tail nick, followed by intraperitoneal injection of 1 gram of 10% dextrose per kilogram body weight. Blood glucose levels were measured by using a glucometer (AlphaTRAK, Abbott Laboratories, Abbott Park, IL) at time 0, 15, 30, 60, 90, and 120 min post glucose dosing.

Additional serum samples were collected 2 days later from these same mice after an 8 h fast for measurement of serum glucose and insulin levels by the Mouse Metabolism Core (Baylor College of Medicine, Diabetes and Endocrinology Research Center, Houston, TX). Cardiac blood was collected following carbon dioxide euthanasia. Sera from 12-mo-old GF (n = 4 females, 4 males) and SPF (n = 3 females, 3 males) SW mice were collected for glucose and glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) levels performed by the Comparative Pathology Laboratory (University of California, School of Veterinary Medicine, Davis, CA).

Histology.

Abdominal organs were evaluated grossly at necropsy and gallbladder, liver, pancreas, and kidneys were fixed in buffered 10% formalin and processed for histology. Formalin-fixed tissues were evaluated from GF SW mice with gallstones (n = 11 females, 7 males; 14.1 ± 1.3 mo old), without gallstones (n = 1 female, 7 males; 10.5 ± 1.2 mo old), and from SPF SW mice without gallstones (n = 6 females, 6 males; 9.5 ± 0.3 mo old). Tissues were embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 4 μm, stained with hematoxylin and eosin (HE), and evaluated by a board-certified veterinary pathologist blinded as to sample identity. Gallbladders were graded semiquantitatively on a scale of 0 (normal) to 3 (severe) for histomorphological changes, including inflammation, edema, hyalinosis, metaplasia, hyperplasia, and dysplasia. The liver, pancreas, and kidneys were qualitatively assessed for any relevant pathology. Because mild liver lesions were observed in some mice, liver sections were further assessed on a scale of 0 to 4 for lobular and portal inflammation, and dysplasia/neoplasia. The number of lobes with >5 inflammatory foci was used to calculate a cumulative hepatitis index score, as previously described (41).

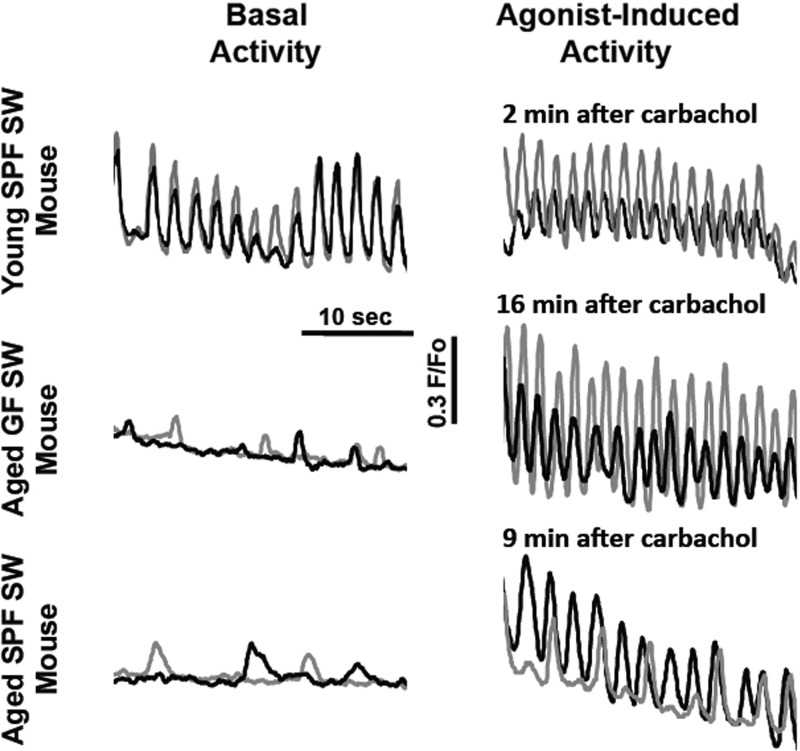

Gallbladder muscle activity.

Calcium imaging studies were performed as previously described in greater detail (25). Age-matched GF and SPF SW female mice (10 mo old; n = 4 per group) were anesthetized with isoflurane, exsanguinated, and underwent cholecystectomy. Gallbladders were opened and mounted serosa side up between two pieces of Sylgard (Dow Corning, Midland, MI) connected by metal pins. Mounted tissues were incubated in HEPES buffer containing 10 μM of fluo-4 AM and 2.5 μg/ml of pluronic acid for 45 min at room temperature, and then rinsed in HEPES buffer for at least 30 min to allow deesterification. The fluo-4-loaded gallbladders were placed in an imaging chamber and superperfused with aerated physiological saline solution (PSS). Ca2+ transients were visualized by using a Nikon TMD inverted microscope with a ×60 water immersion lens attached to a Noran Oz laser confocal system. After a 20-min equilibration period, basal Ca2+ activity was recorded over periods of 30 to 60 s (15–30 frames per second), from 3 to 7 fields per gallbladder. To measure agonist-induced Ca2+ activity, carbachol (3 μM in PSS) was superfused over the tissue, and Ca2+ transients were recorded every few minutes over a 20-min period. Data were analyzed by using SparkAN, a custom software program written at the University of Vermont, and also compared with baseline data obtained from 7- to 10-wk-old SPF SW males.

Responsiveness to exogenous cholecystokinin.

Fasted GF (n = 9 females, 10 males; 8 mo old) and SPF (n = 8 females, 7 males; 8 mo old) SW mice were administered cholecystokinin octapeptide (CCK) to evaluate gallbladder emptying. Under injectable anesthesia described above, mice were injected intravenously with 2 μl/g of CCK solution (10−5 mg/ml sulfated CCK; Tocris Bioscience, Bristol, UK) in sterile PBS, pH 7.4. After 20 min, cholecystectomies were performed, and gallbladder volumes (μl) were determined as described above. Age-matched fasted controls (GF SW mice: n = 9 females, 9 males; SPF SW mice: n = 7 females, 9 males) received an injection of sterile PBS or no injection.

Analysis of conjugated and unconjugated bilirubin in hepatic bile.

Conjugated and unconjugated bilirubin concentrations (μM) and secretion rates (nmol/h) in hepatic bile were determined for unfasted GF (n = 19 females, 8 males; 11.1 ± 0.1 mo old) and SPF (n = 15 females, 7 males; 11.3 ± 0.5 mo old) SW mice. Mice were induced with an anesthetic cocktail administered intraperitoneally as described above. Following cannulation of the hepatic bile duct, hepatic biliary outputs and secretion rates were assessed as previously described (17). To prevent actinic and oxidative degradation of bilirubin, hepatic bile was kept in the dark and/or under red lights. Hepatic biliary species were determined and quantified by HPLC by using the method of Spivak and Yuey (44). Percent UCB (%) was calculated by dividing the concentration of UCB by the sum of the concentrations of all individual bilirubin species (i.e., all mono- and diconjugates, plus UCB). Secretion rates were normalized to 1 h of hepatic bile flow.

Statistics.

Table 1 provides demographic data on SW mice with and without gallstones. Logistic regression was performed to determine the likelihood of SW mice having gallstones (binary variable), controlling for microbial status (GF or SPF; binary variable), age (continuous variable), sex (binary variable), and body weight (continuous variable), and was reported through adjusted (crude) odds ratios (OR), 95% confidence intervals (95% CI), and P values of the overall test of the model and each parameter estimate. For each covariate, the likelihood-ratio chi-squared test for parameter estimates was used to compare the full logistic model with a model excluding the covariate of interest. The favored model included only covariates found to contribute to the predictability of the model. All possible interactions in the favored model were evaluated as a set to determine significance by using a chi-squared test to compare the favored logistic models, with or without the set of interaction variables. Confounders were defined as covariates that, when added to the favored model, resulted in ≥10% change in the slope of the major exposure, microbial status. Further, a stratified logistic regression analysis was performed as described above and was segregated by microbial status, with age as the major exposure and sex and body weight as covariates.

Presence of gallstones, microbial status, age, sex, and body weight were tested against individual quantitative analytes to determine significant effect(s) by analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), also with separate ANCOVAs performed for both microbial statuses. Adjusted means were calculated for both microbial statuses, with the continuous variables (age, body weight) fixed at their means; data was reported as adjusted mean ± standard error. Percentage data (hematocrit, HbA1c, unconjugated bilirubin) were arcsin transformed prior to analysis; reported adjusted mean ± standard error reflects untransformed data.

Where ANCOVAs were not performed, GF and SPF SW mice were compared and further analyzed within both microbial statuses by presence of gallstones and sex. Age and body weight values were also compared between GF and SPF SW mice analyzed by using a two-sample test of group means assuming equal variance (two-tailed), and reported as mean ± standard error. Glucose tolerance testing data was analyzed by using a two-sample test of group means (two-tailed), for comparison between groups at baseline and to determine the level of statistical significance when the difference between the mean area under the curves (AUC), determined by the trapezoidal rule with baselines set at zero, of two groups was considered. Median pathology scores were compared between groups by using a Mann-Whitney two-sample rank-sum test. To analyze gallbladder muscle activity, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Bonferroni adjustment for multiple comparisons between groups was used.

Statistical analysis was performed by using STATA/IC 13.0 for Mac (StataCorp, College Station, TX) and Prism Version 5.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA), with P < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

GF SW mice had markedly enlarged gallbladders, irrespective of gallstones.

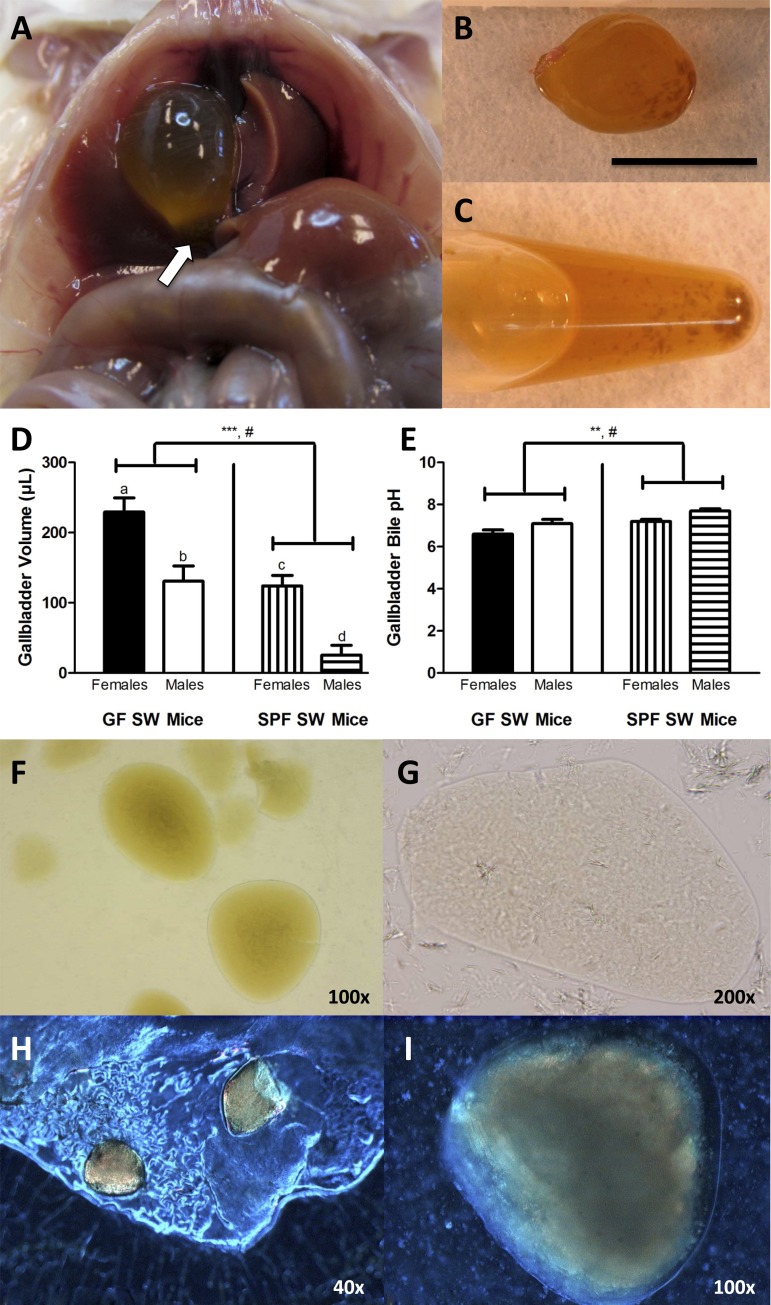

Necropsy of GF SW mice revealed that 169 of 224 mice (75%) showed gallbladders containing grossly visible, variably sized gallstones numbering from few to numerous (Table 1 and Fig. 1, A–C). Fasted and nonfasted GF SW mice had markedly enlarged gallbladders that commonly measured 1.0 cm long by 0.5 cm wide (Fig. 1, A and B). Most SPF SW mice (77%; 98/128) displayed normal-appearing gallbladders with no gross evidence of gallstones (Table 1). However, 15 female and 15 male (23%) gallbladders contained gallstones (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Gallbladders of germfree (GF) Swiss Webster (SW) mice were markedly enlarged, and 75% contained gallstones grossly and microscopically consistent with “black” pigment gallstones. A: twelve-month-old female GF SW mouse with dilated gallbladder containing gallstones (arrow). B: excised gallbladder with gallstones from a 12-mo-old female GF SW mouse. Gallstones were present in varying number, size, and color, but were often dark brown to black, as pictured here. Black bar indicates 1 cm. C: Eppendorf tube containing gallstones and gallbladder bile from a 12-mo-old female GF SW mouse. D and E: gallbladder volumes (μl) and gallbladder bile pHs of SW mice were reported as adjusted mean ± standard error, with age and body weight fixed at their means (n = 41; mean age: 11.4 mo; mean body wt: 44.9 g). Asterisks indicate level of significance of differences in gallbladder volume and bile pH, related to microbial status, with ***P < 0.001 and **P < 0.01; note that the gallbladder bile samples of GF SW mice were acidic. Statistically significant differences in analytes related to sex in the overall model were noted with #, and if also found significant when stratified by microbial status, were marked by a difference in letters (a, b; c, d) (gallbladder volume GF SW mice: P < 0.01; SPF SW mice: P < 0.001). F: gallstones and sediment in gallbladder bile from a 15-mo-old female GF SW mouse at ×100 magnification, under direct light. G: direct light microscopy of a gallstone from a 15-mo-old female specific pathogen-free (SPF) SW mouse viewed at ×200 magnification. H: polarized light microscopy at ×40 magnification of gallstones present on the mucosal surface of the gallbladder of an 11-mo-old GF SW mouse; one gallstone appears to be broken. I: high-magnification view (×100) of a gallstone in gallbladder bile from an 11-mo-old GF SW mouse viewed under polarized light.

GF SW mice (n = 12; 5 females, 4 males with gallstones) exhibited greater gallbladder volumes (179.0 ± 18.8 μl; SPF SW mice: 73.6 ± 11.3 μl) and lower pH of gallbladder bile (6.8 ± 0.1; SPF SW mice: 7.4 ± 0.1) compared with SPF SW mice (n = 29; 1 female, 5 males with gallstones). Statistically significant differences were unrelated to presence of gallstones, age, or body weight, but related to microbial status [gallbladder volume: F(1,35) = 20.37, P < 0.001; gallbladder bile pH: F(1,35) = 11.56, P < 0.01] and sex [gallbladder volume: F(1,35) = 28.51, P < 0.0001; gallbladder bile pH: F(1,35) = 10.31, P < 0.01] (Fig. 1, D and E). When analysis was stratified by microbial status, differences in bile pH according to sex were found to be nonsignificant, whereas significant effects were maintained on gallbladder volume in both GF (P < 0.01) and SPF (P < 0.001) SW mice, with females (GF SW mice: 229.4 ± 20.2 μl; SPF SW mice: 124.0 ± 15.2 μl) containing greater gallbladder volumes than males (GF SW mice: 130.9 ± 21.6 μl; SPF SW mice: 25.6 ± 14.0 μl) (Fig. 1, D and E).

Gallstones developed predominantly in obese, older female GF SW mice.

By using logistic regression, the odds of developing gallstones for GF SW mice was 11 times those of SPF SW mice, controlled for age and body weight (P < 0.001) (Table 2). Additionally, a 1 mo increase in age and a 1-g increase in body weight of SW mice increased the odds of developing gallstones by 15% (P < 0.01) and 5% (P < 0.01), respectively (Table 2). Sex was found nonpredictive in the full model, and no interaction or confounding was demonstrated.

Table 2.

Logistic regression models of the relationship between microbial status (germfree, specific pathogen-free) of Swiss Webster mice and presence of gallstones

| OR | 95% CI | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multivariate full model, n = 344* | <0.0001 | ||

| Microbial status | |||

| GF | 11.44 (10.04) | 6.57–19.93 (6.03–16.71) | <0.001 (<0.001) |

| SPF | Reference group | ||

| Age, mo | 1.14 (1.16) | 1.04–1.26 (1.07–1.27) | <0.01 (<0.001) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 1.55 (1.39) | 0.92–2.60 (0.91–2.12) | 0.10 (0.13) |

| Male | Reference group | ||

| Body weight, g† | 1.05 (1.03) | 1.02–1.09 (1.01–1.06) | <0.01 (<0.05) |

| Multivariate reduced model, n = 344‡ | <0.0001 | ||

| Microbial status | 10.98 | 6.36–18.98 | <0.001 |

| Age, mo | 1.15 | 1.05–1.27 | <0.01 |

| Body weight, g† | 1.05 | 1.02–1.08 | <0.01 |

In multivariate full model, odds ratios (ORs), 95% confidence intervals (CIs) and P values are reported as adjusted (crude).

Eight body weight values not provided.

Favored model; excludes sex found nonsignificant by likelihood-ratio χ2 test.

Stratified logistic regression revealed the odds of developing gallstones for female GF SW mice was three times those of males, controlled for age and body weight (P < 0.01) (Table 3). Further, a 1 mo increase in age and a 1-g increase in body weight of GF SW mice increased the odds of developing gallstones by 23% (P < 0.01) and 8% (P < 0.01), respectively (Table 3). Of the 169 GF SW mice with gallstones, 105 (62%) were females and 64 (38%) were males of similar age. Of the 55 mice without gallstones, 20 (36%) were females and 35 (64%) were males. Stratified logistic regression analysis found no significant predictability for presence of gallstones in SPF SW mice, controlling for age, sex, and body weight.

Table 3.

Logistic regression model of the relationship between independent variables and presence of gallstones in germfree (GF) Swiss Webster (SW) mice

| OR | 95% CI | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multivariate full model, n = 220 | <0.0001 | ||

| Age, mo | 1.23 (1.22) | 1.08–1.40 (1.08–1.39) | <0.01 (<0.01) |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 3.16 (2.87) | 1.58–6.29 (1.53–5.40) | <0.01 (<0.01) |

| Male | Reference group | ||

| Body weight, g* | 1.08 (1.07) | 1.04–1.13 (1.03–1.12) | <0.001 (<0.01) |

In multivariate full model, ORs, 95% CIs, and P values are reported as adjusted (crude). Multivariate full model is favored model; no covariates found nonsignificant by likelihood-ratio χ2 test.

Four body weight values not provided.

Gallstone morphologic features and composition were consistent with black pigment gallstones.

Gallstones were variable in size (all less than 1 mm), and their color ranged from yellow to dark brown to black. On average, gallstones from GF SW mice were grossly dark in color and durable (Fig. 1, A–C), whereas SPF SW gallstones were pale and friable.

Gallstones from GF SW mice viewed under direct light microscopy had well-defined smooth edges and were yellow to light brown on the outside, with a more pigmented, darker brown core (Fig. 1F). By using polarized light microscopy, the outermost aspect of the gallstones was almost translucent and revealed speckles of birefringent material, but not distinct crystals (Fig. 1, H and I). Direct light microscopy of 1 gallstone sample from an SPF SW mouse showed a few gallstones that were much lighter in color and lacked a dark core (Fig. 1G). Direct light microscopy of gallbladder bile from GF and SPF SW mice lacking visible gallstones revealed pale to light brown, amorphous sediment, which was also present in the bile from GF SW mice with gallstones (Fig. 1F).

Gallstones from a 15-mo-old female GF SW mouse analyzed by the Laboratory for Stone Research by polarized light microscopy and infrared spectroscopy were composed of “100%” calcium bilirubinate; note that no crystalline substances were observed, and acid or neutral salts were not defined but were likely Ca(HUCB)2 based on gallbladder bile pH. The remainder of gallstones submitted for analysis contained noncrystalline, undefined proteinaceous material.

Cholesterol content was <1% cholesterol content in all gallstone samples analyzed (GF SW females: 0.7%; GF SW males: 0.6%; SPF SW females: 0.1%). Aerobic and anaerobic cultures of GF and SPF SW gallstones and gallbladder bile were negative.

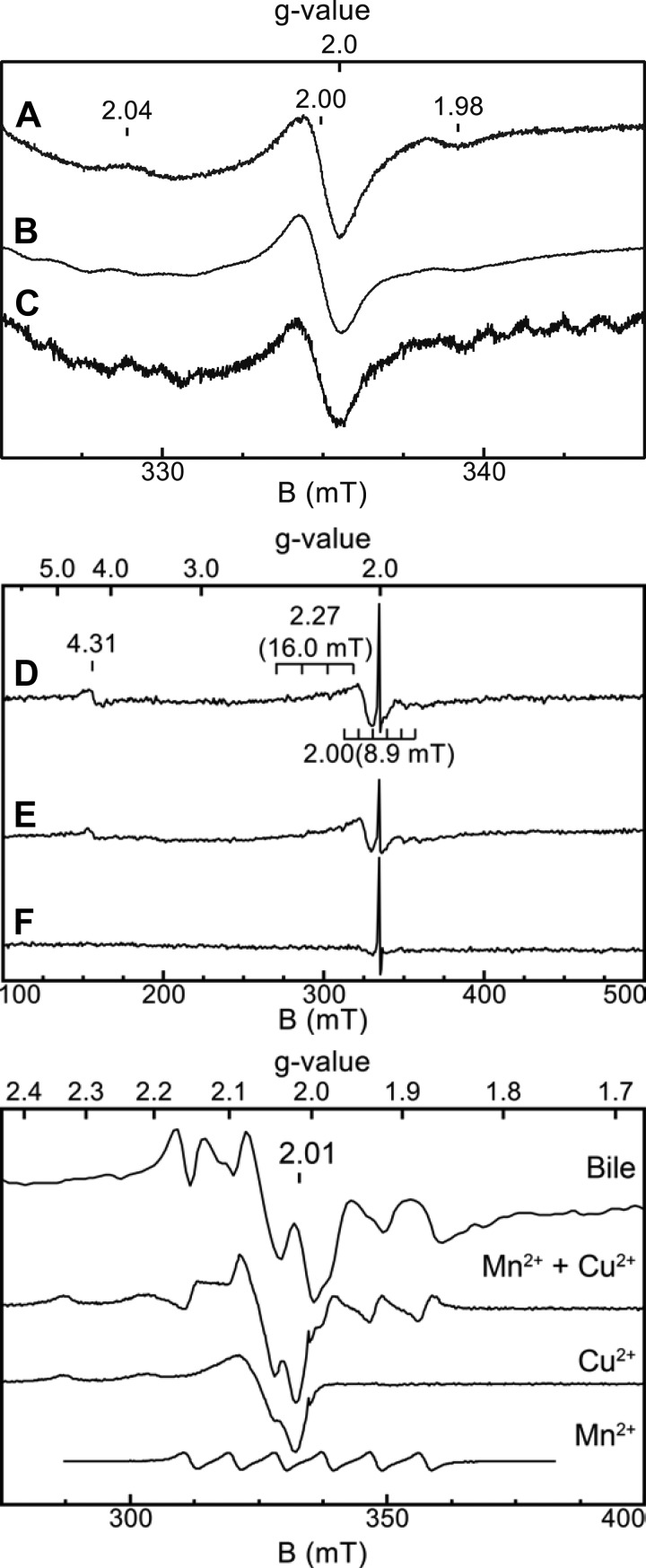

EPR spectroscopic analysis supported the presence of bilirubin radicals in SW gallstones.

Previous reports have indicated the presence of EPR-detectable transition metals ions, specifically Mn2+, Cu2+, and Fe3+, as well as bilirubin radicals in black pigment gallstones (7, 13). In our study, EPR-detectable species were identified in samples of gallstones that were washed 2 (GF SW) and 5 (GF and SPF SW) times, and in gallbladder bile (GF SW). EPR spectroscopic analysis of the gallstones washed 5 times from GF and SPF SW mice revealed features consistent with those observed for commercial bilirubin: the signal centered at g = 2.00 indicates a radical species and is attributed to the presence of bilirubin radicals (Fig. 2, top).

Fig. 2.

Electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectra of gallstones and gallbladder bile. Top: bilirubin (A) and gallstone samples from GF (B) and SPF (C) SW mice, highlighting the organic radical observed at g = 2. A: a sample of commercial bilirubin (10 μM in Chelex-treated Milli-Q water) contained a derivative EPR signal centered at g = 2.00. Additional features were observed at g = 2.04 and g = 1.98. B: EPR spectrum of gallstones obtained from GF SW mice. Spectrum B contained a derivative feature centered at g = 2.0 attributed to bilirubin radicals. An additional feature was observed at g = 1.98. Multiple additional features that display weak signal intensities were observed at lower field and may indicate the presence of additional EPR-detectable species in the sample. C: EPR spectrum of gallstones from one SPF SW mouse. The spectrum is scaled by 5× to facilitate comparison with spectra A and B. A derivative feature centered at g = 2.00 was also observed, and multiple weak features were present in the baseline. Instrument conditions: temperature, 5 K; microwaves, 20.1 μW at 9.4 GHz; modulation amplitude, 1 mT. Middle: EPR spectra of gallstones and gallbladder bile from GF SW mice. D: spectrum of twice-washed gallstones. E: spectrum of undiluted gallbladder bile. F: spectrum of gallstones washed 5 times. Instrument conditions: temperature, 20 K; microwaves, 0.2 mW at 9.4 GHz. Bottom: expanded view of the EPR signals in the g = 2 region from spectrum E. The Mn2+ and Cu2+ signals were obtained from standards of each metal ion (prepared in Milli-Q water). The Mn2+ + Cu2+ spectrum was generated through a linear combination of the Mn2+ and Cu2+ standard spectra. Because it was necessary to record the spectra under nonideal spectroscopic conditions (higher power) to observe and maximize signals for the transition metal ions, the radical signal at g ∼ 2 is saturated, resulting in loss of the characteristic derivative signal that is apparent under ideal spectroscopic conditions in the panels at top and middle. Instrument conditions: temperature, 20 K; microwaves, 0.2 mW at 9.4 GHz.

Signals from EPR-detectable transition metal ions attributed to Mn2+ (g = 2.01, a = 8.9 mT), Cu2+ (g = 2.27, a = 16 mT), and Fe3+ (g = 4.31) were observed in twice-washed gallstones and gallbladder bile obtained from GF SW mice (Fig. 2, middle). Signals from Mn2+ and Cu2+ are visible in the g = 2 region of the spectra, and the expected hyperfine patterns (4-line, a = 16 mT from the I = 3/2 Cu nucleus; 6-line, a = 8.9 mT from the I = 5/2 55Mn nucleus) from these individual species overlap considerably. The observed pattern of lines around g = 2.01 for a gallbladder bile sample (see below) could be accurately reproduced by the summation of spectra obtained for aqueous solutions of Mn2+ and Cu2+ (obtained from commercial atomic absorption standard solutions) (Fig. 2, bottom). Thorough washing (5 times) of gallstones from GF SW mice with Chelex-treated Milli-Q water resulted in loss of the signals attributed to the transition metal ions observed in twice-washed gallstones and in gallbladder bile. The loss of the signals was gradual (i.e., decreased signal intensities with more washing); after five washes, the transition metal ions were either undetectable or significantly reduced (<10% of intensity) compared with gallstones washed twice. In contrast to prior studies, our results show that the transition metal ion signals likely arise from the gallbladder bile rather than the gallstones (7, 13).

Consistent with the presence of bilirubin radicals, a sharp signal at g = 2.00 was also observed in the twice-washed gallstone and gallbladder bile samples. In contrast to the transition metal ion signals, this radical signal persisted in the gallstones washed 5 times, indicating that the signal likely arises from a species in the gallstones themselves (Fig. 2, middle). The possibility of another radical species, or the presence of other radicals that are not detectable under these conditions, cannot be ruled out from these experiments.

Hemograms and urinalysis were normal in GF SW mice, but serum cholesterol was elevated, and serum glucose was positively related to increasing age.

Of the 23 GF and 6 SPF SW mice evaluated for CBC, 9 female and 7 male GF SW mice had gallstones, while only 1 female SPF SW mouse showed gallstones. There were no statistically significant differences in CBC analytes related to presence of gallstones, microbial status, age, sex, or body weight in SW mice, and all analytes were comparable to reference values (Table 4) (14, 21).

Table 4.

Complete blood count analytes from germfree and specific pathogen-free Swiss Webster mice

| GF SW Mice |

SPF SW Mice |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Complete Blood Count | Female, n = 11 | Male, n = 12 | Female, n = 3 | Male, n = 3 | Reference Values |

| White blood cell count, 103/μl | 4.9 ± 0.8 | 4.3 ± 0.7 | 4.0 ± 1.4 | 4.3 ± 1.4 | 5.1–11.6 |

| Neutrophils | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 1.7 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.5 | 1.7 ± 0.5 | 0.3–4.3 |

| Bands | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.2 ± 0.1 | 0.1 ± 0.1 | none to few |

| Lymphocytes | 2.6 ± 0.5 | 2.5 ± 0.5 | 2.6 ± 0.9 | 2.5 ± 1.0 | 3.2–8.7 |

| Monocytes | 0.1 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0–0.3 |

| Eosinophils | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.1–0.4 |

| Basophils | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0–0.2 |

| Red blood cell count, 106/μl | 10.3 ± 0.3 | 10.7 ± 0.3 | 9.7 ± 0.5 | 10.2 ± 0.6 | 7–11 |

| Hematocrit, % | 48.8 ± 1.5 | 49.7 ± 1.4 | 51.9 ± 2.6 | 52.7 ± 2.7 | 35–52 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dl | 13.6 ± 0.3 | 14.2 ± 0.3 | 13.9 ± 0.6 | 14.5 ± 0.6 | 10–17 |

| Platelet Count, 103/μl | 1,239 ± 147 | 1,426 ± 131 | 1,417 ± 246 | 1,604 ± 255 | 900–1,600 |

| Mean corpuscular volume, fl | 47.7 ± 1.0 | 46.4 ± 0.9 | 53.3 ± 1.8 | 52.0 ± 1.9 | 45–55 |

| Mean corpuscular Hemoglobin (pg/cell) | 13.3 ± 0.3 | 13.2 ± 0.2 | 14.3 ± 0.4 | 14.2 ± 0.5 | 15–18 |

| MCH concentration, g/dl | 27.9 ± 0.6 | 28.5 ± 0.6 | 26.8 ± 1.1 | 27.4 ± 1.1 | 30–38 |

There were no statistically significant differences in analytes determined by ANCOVA related to presence of gallstones, microbial status, age, sex, or body weight. GF SW and SPF SW data represent adjusted mean ± standard error, where age and body weight are fixed at their means (n = 29; mean age: 11.1 mo; mean body wt: 44.7 g). Of those analyzed, 16 GF SW mice and 1 SPF SW mouse had gallstones. Reference data for SW mice are not published, and reference intervals provided represent normative data for the mouse, and are not specific for strain, sex, or age (14, 21).

No statistically significant differences in serum chemistry analytes analyzed by IDEXX from 26 GF SW and 9 SPF SW mice were related to presence of gallstones (GF SW mice: n = 10 females, 6 males with gallstones; SPF SW: n = 0 with gallstones), but microbial status, age, sex, and body weight had significant effect(s) (Table 5). Serum chemistries were unremarkable except for elevated serum cholesterol in GF SW, and elevated serum glucose in GF and SPF SW mice compared with the reference values (Table 5) (21, 39, 40). Differences in serum cholesterol were related to microbial status [F(1,23) = 4.96, P < 0.05], with GF SW mice (245 ± 12 mg/dl) having higher values than SPF SW mice (174 ± 28 mg/dl), controlled for presence of gallstones, age, sex, and body weight. Differences in serum glucose were related to increasing age [F(1,29) = 15.29, P < 0.001], with the effect pronounced in GF SW mice (238 ± 14 mg/dl, P < 0.01; SPF SW mice: 219 ± 27 mg/dl). The remaining differences (indirect bilirubin, alanine aminotransferase, blood urea nitrogen, phosphorus) were evaluated but not clinically meaningful, as noted in Table 5.

Urine samples from GF SW mice (n = 14; 8 females, 1 male with gallstones) appeared grossly normal and were negative for bilirubin and glucose. Urobilinogen levels were ≤0.2 mg/dl, which was the lowest detectable limit of the urinalysis strip. Ketonuria (5.0 to 80 mg/dl) was observed in 5 female mice, 4 of which had gallstones, and protein levels varied from none to 100 mg/dl. Urine pH was 6.0 in all samples, and the specific gravity of 5 urine samples ranged from 1.010 to 1.025. Urine samples from 5 female SPF SW retired breeders, 2 of which had gallstones, were also negative for glucose, and were otherwise within normal clinical limits.

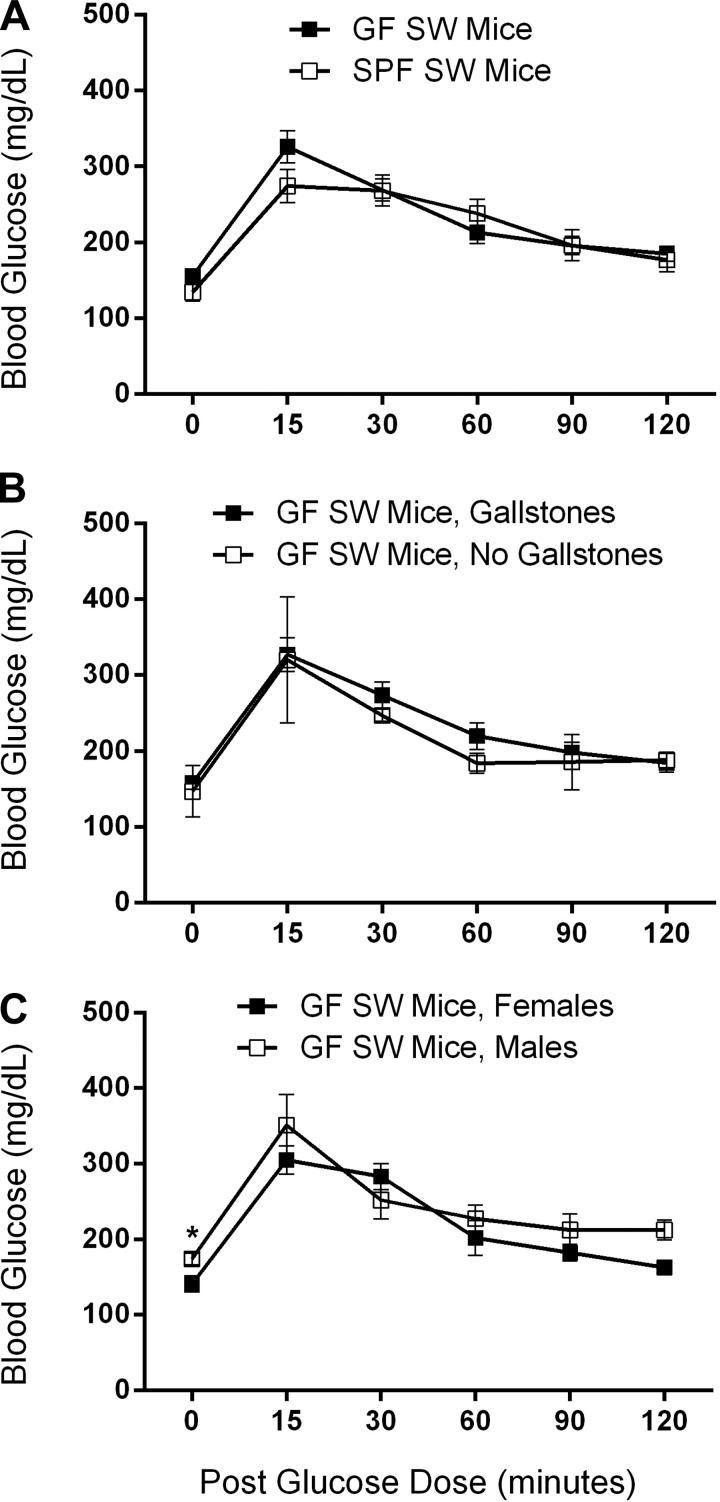

Glucose tolerance testing in GF and SPF SW mice was normal.

Glucose tolerance testing of 9-mo-old GF (n = 11; 5 females, 4 males with gallstones) and SPF (n = 12; 3 females, 1 male with gallstones) SW mice was normal (Fig. 3). There were no significant differences in baseline blood glucose between groups, except that GF SW males (174 ± 8 mg/dl) had slightly higher levels compared with GF SW female mice (141 ± 11 mg/dl) (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3). The mean AUCs of all groups were statistically the same (Fig. 3). There was no significant difference between the body weights of the GF (48.8 ± 1.0 g) and SPF (48.5 ± 2.0 g) SW mice evaluated for diabetes, including by sex, though mice were obese.

Fig. 3.

Normal glucose tolerance testing results from 9-mo-old GF SW and SPF SW mice. The mean area under the curves of all groups compared were statistically the same, including not pictured SPF SW mice with or without gallstones, and SPF SW females or males. A: GF SW mice (n = 11; 79.8 ± 6.9) compared with SPF SW mice (n = 12; 93.8 ± 6.9). B: GF SW mice with gallstones (n = 9; 80.5 ± 7.9) compared with GF SW mice without gallstones (n = 2; 77.0 ± 15.0). C: GF SW females (n = 6; 84.2 ± 9.8) compared with GF SW males (n = 5; 74.6 ± 9.9). Mean baseline blood glucose values were significantly higher in GF SW male mice compared with GF SW female mice; *P < 0.05.

Additionally, there were no significant differences in serum glucose (GF SW mice: 167 ± 24 mg/dl; SPF SW mice: 210 ± 22 mg/dl) or insulin (GF SW mice: 2.6 ± 0.9 ng/ml; SPF SW mice: 3.5 ± 0.8 ng/ml) levels of 9-mo-old SW mice, related to presence of gallstones, microbial status, age, sex, or body weight. There was also no significant difference in HbA1c levels (GF SW mice: 4.3 ± 0.2%; SPF SW mice: 4.1 ± 0.2%) of 12-mo old SW mice (GF SW mice: n = 8; 4 females, 4 males with gallstones; SPF SW mice: n = 6; 1 female with gallstones), but increasing body weight positively related to serum glucose [F(1,9) = 8.08, P < 0.05] in SPF SW mice (162 ± 28 mg/dl, P < 0.05; GF SW mice: 251 ± 22 mg/dl). Note that two HbA1c levels were below the detectable limit, so the lowest registered levels were used for statistical analysis (GF SW mouse: <3.83%; SPF SW mouse: <3.59%).

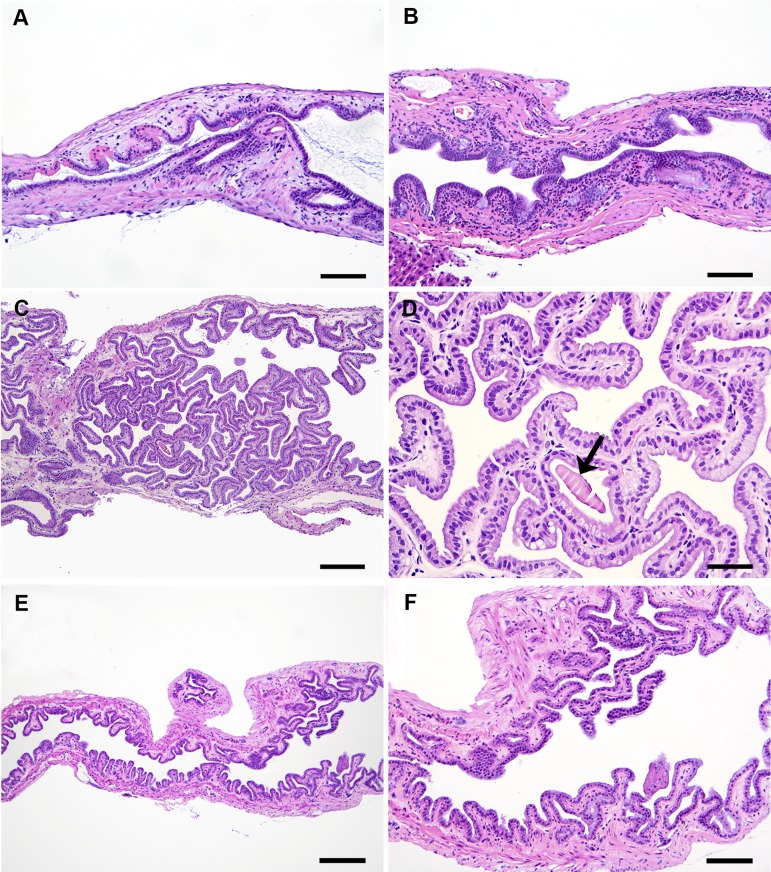

GF SW mice developed low-grade gallbladder and portal inflammation, compared with SPF SW mice.

Of the 26 GF SW mice evaluated histologically, 18 mice had gallstones, though presence of gallstones had no effect on gallbladder lesion scores. Tissue samples from SPF SW mice with gallstones were not evaluated histologically, but 12 SPF SW mice without gallstones were examined. Compared with SPF SW mice that had none to minimal gallbladder pathology (Fig. 4, E and F), GF SW mice had mild to moderate (i.e., low grade) inflammation of the gallbladder (median: 1.0; range: 0.3–2.5; P < 0.001), with mononuclear infiltrates consisting predominantly of lymphocytes, plasma cells, and macrophages, with variable numbers of neutrophils and mast cells (Fig. 4, A–D). Mild to moderate edema (median: 1.0; range: 0.0–2.0; P < 0.05) and epithelial hyperplasia (median: 1.0; range: 0.0–2.0; P < 0.01) had also developed, while hyalinosis, metaplasia (GF SW males > females; P < 0.05), and dysplasia were absent or minimal (Fig. 4, A–D).

Fig. 4.

Hematoxylin and eosin images of the range of gallbladder lesions in GF SW (A–D) compared with SPF SW (E and F) mice. A: gallbladder of an 8-mo-old male GF SW mouse with gallstones, showing mild subepithelial inflammation, edema, and epithelial hyalinosis (intensely eosinophilic granular hyaline-like cytoplasmic alteration). B: gallbladder of an 8-mo-old female GF SW mouse without gallstones showing moderate mixed (lymphocytic and granulocytic) inflammation of the epithelium and stroma with minimal papillary epithelial projections. C: low-magnification image of a gallbladder of an 8-mo-old male GF SW mouse without gallstones showing prominent papillomatous epithelial hyperplasia, scattered inflammatory cells, and edema in the subepithelial space/stroma. D: higher magnification of C, showing hyperplastic long columnar epithelium with mostly basal oval nuclei, abundant eosinophilic to vacuolated (mucous) cytoplasm, and an intraglandular protein cast (arrow). E and F: low- and high-magnification images of a gallbladder of a 10-mo-old male SPF SW mouse with sparse inflammatory cells and mild papillary epithelial hyperplasia. Bars: A, B, and F = 80 μm; C and E = 160 μm; D = 40 μm.

SPF SW mice showed no or only minimal inflammation in the liver, whereas GF SW mice displayed significantly higher hepatitis index scores (median: 0.5; range: 0.0–4.0; P < 0.05) than SPF SW mice consisting of minimal to mild mononuclear portal inflammation (median: 0.5; range: 0.0–2.0; P < 0.001), minimal to mild biliary hyperplasia (associated with gallstones, P < 0.05), and variable hepatocellular fatty change in a few mice. Three GF SW mice had unrelated liver pathology, including vascular lesions and lymphoma and, hence, were not used for quantitative liver lesion analysis.

The pancreas of most mice was normal with adequate size and distribution of islets. However, in a few mice there was some segmental lobular reduction in islet size/number, and small perivascular and periductal mononuclear cellular aggregates in one or two foci, with or without intraislet infiltration. The kidneys of a majority of GF and SPF SW mice contained variable degrees of background pathological changes consistent with lymphoma and glomerulonephritis/nephropathy. Of those mice evaluated histologically, GF SW mice (13.0 ± 1.0 mo old) were older than SPF SW mice (9.5 ± 0.3 mo old) (P < 0.05), but body weights were the same.

Aged GF and SPF SW mice had decreased basal activity and altered agonist-induced activation of the gallbladder smooth muscle.

Gallbladder smooth muscle activity can be assessed by evaluating Ca2+ transients under resting conditions and in response to agonist application. Ca2+ flashes correspond to synchronous smooth muscle action potentials, which are initiated by interstitial cells of Cajal in the gallbladder, and Ca2+ waves are transient increases in Ca2+ release from intracellular stores (2, 3, 26). Gallbladder smooth muscle activity was evaluated in four 10-mo-old female GF SW mice with gallstones and four age-matched female SPF SW mice, one with gallstones. Basal activity of both aged GF and SPF SW mouse gallbladder smooth muscle was quiescent, with only occasional Ca2+ waves observed; however, carbachol induced rhythmic, synchronized Ca2+ flashes were present in three of four preparations from both groups (Fig. 5). The frequencies of the agonist-induced flashes in aged GF (0.32 ± 0.06 Hz) and SPF (0.42 ± 0.01 Hz) SW mice were comparable, but were slower than the Ca2+ flash frequencies observed in 7- to 10-wk-old SPF SW mice (0.63 ± 0.02 Hz; P < 0.05) 2–10 min after the application of the agonist. In young SPF SW mice, the peak flash frequency in response to carbachol occurred within 2–10 min, and this was also observed in aged SPF SW mice. However, in 2 of the 3 responsive-aged GF SW mice, the peak in flash frequency was not reached until 15–18 min.

Fig. 5.

Gallbladder smooth muscle activity is disrupted in aged GF and SPF SW mice. Ca2+ transient recordings from pairs of gallbladder smooth muscle cells (gray and black) showing an age-related disruption in spontaneous activity. Gallbladder smooth muscle cells in young SPF SW mice exhibit synchronized rhythmic Ca2+ flashes (panel at top left). Ca2+ flash activity is absent in 10-mo-old GF and SPF SW mice (panels at middle and bottom left), where only Ca2+ waves were detected. Carbachol (3 μM) induced Ca2+ flashes in all three groups of mice once peak frequency was reached (panels at right; time point indicated above each trace).

GF SW mice demonstrated impaired gallbladder emptying in response to CCK.

GF (n = 19; 7 females, 8 males with gallstones) and SPF (n = 15; 1 female, 3 males with gallstones) SW mice were evaluated for responsiveness to exogenous CCK by determination of % gallbladder emptying through comparison of gallbladder volumes with mice receiving no CCK (GF SW mice: n = 18; 7 females, 9 males with gallstones; SPF SW mice: n = 16; 0 females, 5 males with gallstones). Data from control mice injected with sterile PBS or no injection were combined into one group after it was determined that gallbladder volumes were identical between control groups.

Significant differences in gallbladder volume determined by ANCOVA were unrelated to presence of gallstones, age, or body weight but related to microbial status [control mice: F(1,29) = 35.82, P < 0.0001; experimental mice: F(1,29) = 31.60, P < 0.0001] and sex [control mice: F(1,29) = 8.82, P < 0.01] (Fig. 6). GF SW mice showed greater gallbladder volumes in both CCK dose groups (control mice: 170.1 ± 10.5 μl; experimental mice: 142.4 ± 12.4 μl), compared with SPF SW mice (control mice: 64.3 ± 11.3 μl; experimental mice: 15.0 ± 14.7 μl) (Fig. 6). When analysis was stratified by microbial status, a difference in gallbladder volume in GF SW controls due to sex was found to be nonsignificant, whereas a significant effect was maintained in SPF SW controls (P < 0.0001), with females (87.3 ± 15.4 μl) possessing greater gallbladder volumes than males (43.8 ± 11.5 μl) (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

GF SW mice showed impaired cholecystokinin (CCK)-induced gallbladder emptying, compared with SPF SW mice. Gallbladder volumes (μl) of SW mice were reported as adjusted mean ± standard error, with age and body weight fixed at their means (control mice: n = 34; mean age: 8.0 mo; mean body wt: 55.0 g; experimental mice: n = 34; mean age: 8.0 mo; mean body wt: 55.7 g). Asterisks indicate level of significance of differences in gallbladder volumes of control and experimental mice, related to microbial status, with ****P < 0.0001. Statistically significant differences in gallbladder volume related to sex in the overall model were noted by #, and if also found significant when stratified by microbial status, were marked by a difference in letters (a, b) (SPF SW mice: P < 0.0001). A difference in numbers (1, 2) denotes a statistically significant difference in gallbladder volume between SPF SW control and experimental mice (P < 0.0001).

No significant difference was found in gallbladder volume related to CCK dose group in GF SW mice, but there was a difference in SPF SW mice (P < 0.0001), where SPF SW mice receiving CCK (15.0 ± 14.7 μl) showed lower gallbladder volumes than mice in the control group (64.3 ± 11.3 μl) (Fig. 6). Compared with SPF SW mice, GF SW mice exhibited substantially reduced gallbladder emptying in response to CCK; GF SW female mice demonstrated 29.0% emptying compared with 89.0% emptying in SPF SW female mice, and only 1.2% emptying occurred in GF SW males, with 53.4% emptying in SPF SW males (Fig. 6).

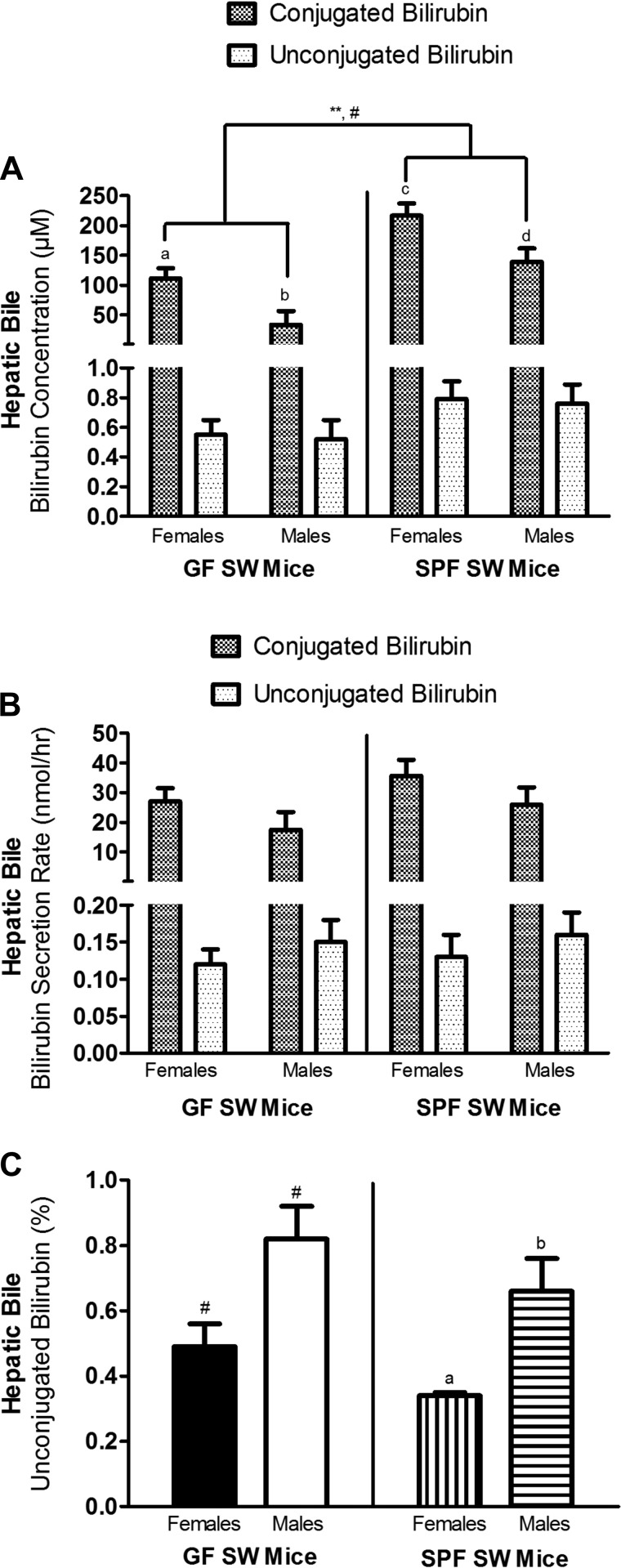

SW mice showed no evidence of induced enterohepatic cycling of unconjugated bilirubin.

GF (n = 27; 18 females, 8 males with gallstones) and SPF (n = 22; 3 females, 1 male with gallstones) SW mice were evaluated for EHC of UCB by determination of bilirubin concentrations (μM), bilirubin secretion rates (nmol/h), and % UCB in the hepatic bile. Significant differences were unrelated to presence of gallstones or body weight, but related to microbial status [conjugated bilirubin concentration: F(1,43) = 11.66, P < 0.01], age [UCB concentration: F(1,43) = 6.12, P < 0.05; UCB secretion rate: F(1,43) = 4.39, P < 0.05; inverse relationships], and sex [conjugated bilirubin concentration: F(1,43) = 14.38, P < 0.001; % UCB: F(1,43) = 13.28, P < 0.001] (Fig. 7). GF SW mice had lower conjugated bilirubin concentrations (87.6 ± 16.3 μM) compared with SPF SW mice (193.0 ± 19.0 μl) (Fig. 7A).

Fig. 7.

GF SW and SPF SW mice were comparable in concentration, secretion rate and % of unconjugated bilirubin (UCB) in hepatic bile. Bilirubin concentrations (μM) (A), secretion rates (nmol/h) (B), and % UCB of hepatic bile (C) of SW mice were reported as adjusted mean ± standard error, with age and body weight fixed at their means (n = 49; mean age: 11.2 mo; mean body wt: 54.8 g). Asterisks indicate level of significance of difference in conjugated bilirubin concentration, related to microbial status, with **P < 0.01. Statistically significant differences in analytes related to sex in the overall model were noted by #, and if also found significant when stratified by microbial status, were marked by a difference in letters (a, b; c, d) (conjugated bilirubin concentration GF SW mice: P < 0.01; SPF SW mice: P < 0.05; % UCB SPF SW mice: P < 0.05).

When analysis was stratified by microbial status, differences in % UCB due to sex in GF SW mice and differences in UCB concentration and secretion rate due to age in GF and SPF SW mice were found nonsignificant. Significant effects were maintained on conjugated bilirubin concentrations in both GF (P < 0.01) and SPF (P < 0.05) SW mice, with females (GF SW mice: 111.4 ± 16.8 μM; SPF SW mice: 216.8 ± 20.7 μM) having greater conjugated bilirubin concentrations than males (GF SW mice: 33.7 ± 22.8 μM; SPF SW mice: 139.1 ± 22.4 μM). Likewise, % UCB in SPF SW mice was greater in males (females: 0.34 ± 0.09%; males: 0.66 ± 0.10%; P < 0.05) (Fig. 7, A and C).

DISCUSSION

This study documented gallstones morphologically and compositionally consistent with “black” pigment gallstones of humans in 84% of females and 65% of males, for an overall prevalence of 75% (169/224) in GF SW mice (23, 33). The classic etiologic associations between black pigment gallstones in humans and chronic hemolysis and ineffective erythropoiesis were not detected in GF SW mice, as hemograms reflected normal erythroid values and morphology. Likewise, GF SW mice did not have increased concentration, secretion rate, or % of UCB in hepatic bile, showing a lack of EHC of UCB. Markedly enlarged gallbladders were observed in GF SW mice with impaired CCK-induced gallbladder emptying and inactive Ca2+ responses, consistent with an inherent abnormal gastrointestinal physiology in GF mice characterized by slower intestinal transit (9, 34, 35, 50, 59). The combination of impaired responsiveness to CCK, weak basal smooth muscle activity, and excess sediment may have contributed to biliary stasis, though a strictly mechanical effect on gallbladder motility due to presence of gallstones is highly unlikely, as GF SW mice with and without gallstones had enlarged fasting gallbladders and impaired gallbladder emptying in response to CCK. Exposure to gut microbiota also appeared to protect against the formation of black pigment gallstones, as only 30 of 128 SPF SW mice developed gallstones (23%). Our findings suggest genetic, age, sex, and body weight predispositions and impaired gallbladder motility, along with a microbiota-associated protective component to the pathogenesis of black pigment gallstone formation in SW mice.

The apparent genetic predisposition and age-related increases in prevalence of black pigment gallstones in GF SW mice are similar to the epidemiology of pigment gallstone disease in humans (5, 32). In humans, genetic factors may be responsible for at least 25% of symptomatic gallstone disease, although the true role of heredity is likely underestimated because of undetected asymptomatic prevalence (22, 32, 46). SW mice are an outbred stock with a long history of experimental study since 1932; however, a known genetic predisposition to black pigment gallstones in either the GF or SPF status has not been noted (6). Given that pigment gallstones have only been observed in our colony of GF SW mice, and not in three other strains of GF mice on distinct genetic backgrounds, the mechanism(s) underlying formation in SW mice may involve one or more spontaneous mutations affecting gastrointestinal physiology, glucoregulatory function, or lipopigment metabolism.

Specifically, physiologically important mutations or altered regulation may have occurred in genes of the gut-liver axis, such as fibroblast growth factor 15 (FGF15) and CCK, which regulate gallbladder filling and emptying, respectively (8, 11, 37). A recent study established a mechanism in GF SW mice whereby increased tauro-beta-muricolic acid acts as a naturally occurring farnesoid X receptor (FXR) antagonist, with subsequent downregulation of FGF15 (42). In a nonsterile gut, bile acids are known to induce FGF15 synthesis and suppress CCK secretion, with FGF15 opposing actions of CCK on the gallbladder (8, 42). It has been previously shown that GF mice have a lower concentration of CCK in the intestinal tract and delayed intestinal transit (34, 35, 50). One of the roles of the commensal gut microbiota may be to increase CCK concentration in order to maintain intestinal transit to promote colonization resistance to pathogenic bacteria (34, 35, 50). The interaction between FGF15 and CCK in GF mice has not been studied directly, but it is likely that the above described downregulation of FGF15 and the lower concentration of CCK in the intestinal tract in GF mice both play a role in gallbladder dysfunction (34, 35, 42).

Furthermore, our study showed that female GF SW mice are 3 times more likely to develop pigment gallstones than males. Both GF and SPF SW female mice had greater fasting gallbladder volumes compared with males, which may be due to the inhibitory effect of progesterone on the contractility of gastrointestinal smooth muscle, including the gallbladder, acting through multiple signaling pathways (24). Gallbladder stasis can occur in pregnant women and is due to high progesterone increasing fasting residual gallbladder volume and decreased emptying capacity (24).

Evaluation of spontaneous and agonist-activated Ca2+ transients (increases in intracellular [Ca2+]) in gallbladder smooth muscle has previously been validated as a useful approach for evaluating muscle activity (2, 3). Normal gallbladder smooth muscle activity is typically associated with rhythmic, spontaneous Ca2+ flashes that correspond to action potentials occurring simultaneously in all cells of a muscle bundle, and are used as an index of basal smooth muscle tone of the gallbladder (2, 3). Additionally, transient, spontaneous Ca2+ waves represent Ca2+ release from inositol triphosphate channels (2). Aged GF and SPF SW mice both had deficits in basal and agonist-induced gallbladder smooth muscle activity, compared with young SPF SW mice. Defects in gallbladder muscle function may reflect oxidative stress damage observed with older age, among other factors, and promote formation of a small nucleus of precipitated calcium bilirubinate, the principal component of black pigment gallstones, with subsequent growth by accretion (2, 11, 20). Furthermore, free radical attack of singlet oxygen may have contributed to polymerization and oxidation of calcium bilirubinate, wherein free radical signal amplitude likely generated from UCB was linearly correlated with pigment content of gallstones (4, 13, 54).

Irrespective of grossly observable gallstones, GF SW mice developed mild to moderate gallbladder inflammation, edema, and epithelial hyperplasia, and mild portal inflammation, compared with SPF SW mice. Gallbladder inflammation may have resulted from the toxic or immune response-modulating properties of UCB and/or from free radical-mediated oxidative stress (43, 54). Cholecystitis in cholesterol gallstone disease has been associated with impaired gallbladder motility, including altered CCK-induced smooth muscle contraction, but has not been found to contribute to gallbladder stasis in black pigment gallstone formation (16, 31, 37, 51). We reason that the observed mild pathology in the gallbladders of GF SW mice both contributed to and resulted from impaired gallbladder motility.

The increased prevalence of black pigment gallstones, particularly in older and heavier female GF SW mice, is consistent with a previous report by our group (28). Gallstones lacking cholesterol content were found as an incidental finding in aged, obese female SPF SW mice that were part of a breeding colony used to characterize a male-predominant SPF SW mouse model of noninsulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (28). Type II diabetes mellitus was not substantiated in GF or SPF SW mice by normal glucose tolerance testing, mean fasting serum glucose levels below 300 mg/dl, an absence of glucosuria, and normal insulin and HbA1c levels (28, 39, 40). Although, there was a positive relationship between serum glucose and age in GF SW mice. Hyperglycemia inhibits bile secretion from the liver and impairs gallbladder contraction, leading to bile stasis and gallstone formation, and is augmented by diabetic autonomic neuropathy (5, 12, 37, 54). One study found that diabetic Taiwanese were twice as likely to develop presumed pigment gallstones, compared with nondiabetic patients (5, 15). Increased risk for both pigment and cholesterol gallstones in humans with diabetes mellitus is most likely due to metabolic syndrome and is confounded by age, obesity, and a family history of gallstones (5, 45, 46). Epigenetic factors, specifically variations in gut microbiota, have been causally linked to the development of diabetes (1, 16, 29). A potential genetic predisposition to diabetes and/or a tendency for development of metabolic syndrome in SW mice, combined with differences in exposure to microbes, all likely play a role in the observed variations in glucoregulatory function and lipid metabolism in SW mice.

As in cholesterol gallstone disease, cholesterol may also play a role in the observed increased fasting gallbladder volumes and impaired CCK-induced gallbladder emptying in GF SW mice documented in this study. Biliary hypersecretion of cholesterol can cause gallbladder immotility, and prolonged intestinal transit may allow for hyperabsorption of cholesterol from the gut (27, 36, 37, 58, 60, 61). Cholesterol incorporation into the sarcolemmal membranes of gallbladder and intestinal smooth muscle cells decreases turnover of CCK-1R, the cognate receptor of CCK-8, with subsequent interrupted ligand-receptor interaction, thus impairing muscle contraction through blocked CCK signaling (10, 36, 37, 58, 61). This relationship has been elucidated with a targeted deletion of CCK-1R in mice showing increased gallstone susceptibility, delayed small intestinal transit, and increased biliary cholesterol secretion, and more recently in CCK knockout mice with enlarged fasting gallbladder volumes and impaired postprandial response of the gallbladder (57, 58, 61). Also, increased susceptibility to cholesterol gallstones in GF mice compared with mice with indigenous microbiota was related to larger gallbladders and gallbladder inflammation (16).

One study using human subjects found that patients with black pigment gallstones had moderately impaired gallbladder motility characterized by delayed and incomplete postprandial emptying, but these patients had normal fasting gallbladder volumes and biliary cholesterol saturation indices (36). Irrespective that Portincasa et al. (36, 37) reported human patients with black pigment gallstones do not have excess biliary cholesterol, this mechanism is still worthwhile to explore in GF SW mice with known delayed intestinal transit and increased serum cholesterol levels. The hypomotile gallbladder of GF SW mice may not only be prolonging the residence time of UCB, but also of cholesterol (36, 58). Defective interaction of CCK with CCK-1R may also explain why GF SW mice did not respond to exogenously administered CCK as robustly as SPF SW mice. Another possibility is that, because of the lower CCK concentration in the small intestine of GF mice, receptors may be present in lower numbers. A combination of decreased intestinal concentration of CCK and density of CCK-1 receptors, from cholesterol incorporation in the gallbladder and/or receptor downregulation, may both contribute to the major defects observed in gallbladder motility and subsequent black pigment gallstone formation in GF SW mice.

This study documents a systematic and detailed description of a new animal model of black pigment gallstone formation and suggests additional experiments to elucidate the molecular mechanism(s) that are responsible for cholelithogenesis. Further studies could probe the possibility of biliary cholesterol supersaturation as a factor in the observed impaired gallbladder motility in GF SW mice. This work could involve complete hepatic and gallbladder bile chemistry profiles of GF and SPF SW mice, tests to determine cholesterol content in the gallbladder smooth muscle, and gene expression analyses, most importantly of CCK-1R. Future experiments should also explore the altered gut-liver axis in a sterile gut, specifically the interplay of FGF15 and CCK on gallbladder function, and the gallstone protective components of the commensal microbiota.

We theorize that features of GF physiology, including decreased intestinal CCK concentration and delayed intestinal transit, as well as an apparent genetic predisposition of the SW stock, contributed to the spontaneous formation of black pigment gallstones in GF SW mice. It is likely that histomorphological alterations in the gallbladder, progesterone in females, increasing serum glucose with age, obesity and a predisposition to diabetes and/or metabolic syndrome, and elevated serum cholesterol all played a role in the increased fasting residual gallbladder volume, weak basal gallbladder smooth muscle activity, and impaired CCK-induced gallbladder emptying. GF SW mice should continue to be a valuable animal model to study impaired gallbladder motility as one contributing cause of black pigment gallstones in humans in the absence of hyperbilirubinbilia.

GRANTS

This work was largely supported by NIH training grant T32-OD10978-26 and P30-ES002109 to J.G.F. We also acknowledge BCM Diabetes and Endocrinology Research Center grants (P30 DK079338), DK080480, and DK62267 to G.M.M., the services of the Mouse Metabolism Core, DK036588 to M.C.C., and the Kinship Foundation Searle Scholar Award to E.M.N.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.E.W., M.R.L., J.A.H., B.L., M.T.W., G.M.M., E.M.N., M.C.C., and J.G.F. conception and design of research; S.E.W., M.R.L., J.A.H., M.B.B., K.R.B., B.L., and S.M. performed experiments; S.E.W. analyzed data; S.E.W., M.R.L., J.A.H., M.B.B., K.R.B., B.L., S.M., M.T.W., G.M.M., E.M.N., M.C.C., and J.G.F. interpreted results of experiments; S.E.W., J.A.H., M.B.B., B.L., and S.M. prepared figures; S.E.W. drafted manuscript; S.E.W., M.R.L., J.A.H., M.B.B., B.L., S.M., M.T.W., G.M.M., E.M.N., M.C.C., and J.G.F. edited and revised manuscript; S.E.W., M.R.L., J.A.H., M.B.B., K.R.B., B.L., S.M., M.T.W., G.M.M., E.M.N., M.C.C., and J.G.F. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Shikshya Shrestha and Jon David P. Andrade for assistance with cholecystectomies, gallbladder bile collection, and analysis, as well as their helpful suggestions and critical insights. We also thank Carlos Umana for his precise and dedicated care of the GF SW mouse colony and for greatly assisting with GTT performed under aseptic conditions, and Oscar Acevedo for GF SW husbandry. Lastly, we acknowledge and thank the necropsy technicians (Lenzie Cheaney, Michelle Graffam, Christian Kaufman, Melissa Mobley, Amanda Potter, and Jesse Schacht) who have assisted with sample and data collection.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alam C, Bittoun E, Bhagwat D, Valkonen S, Saari A, Jaakkola U, Eerola E, Huovinen P, Hanninen A. Effects of a germ-free environment on gut immune regulation and diabetes progression in non-obese diabetic (NOD) mice. Diabetologia 54: 1398–1406, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Balemba OB, Heppner TJ, Bonev AD, Nelson MT, Mawe GM. Calcium waves in intact guinea pig gallbladder smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 291: G717–G727, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balemba OB, Salter MJ, Heppner TJ, Bonev AD, Nelson MT, Mawe GM. Spontaneous electrical rhythmicity and the role of the sarcoplasmic reticulum in the excitability of guinea pig gallbladder smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 290: G655–G664, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cahalane MJ, Neubrand MW, Carey MC. Physical-chemical pathogenesis of pigment gallstones. Semin Liver Dis 8: 317–328, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen CY, Lu CL, Huang YS, Tam TN, Chao Y, Chang FY, Lee SD. Age is one of the risk factors in developing gallstone disease in Taiwan. Age Ageing 27: 437–441, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chia R, Achilli F, Festing MF, Fisher EM. The origins and uses of mouse outbred stocks. Nat Genet 37: 1181–1186, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chikvaidze E, Tabutsadze T, Gogoladze T, Datuashvili G, Iremashvili B. Ternary complexes of albumin-Mn(II)-bilirubin and electron spin resonance studies of gallstones. Georgian Med News 168: 11–15, 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi M, Moschetta A, Bookout AL, Peng L, Umetani M, Holmstrom SR, Suino-Powell K, Xu HE, Richardson JA, Gerard RD, Mangelsdorf DJ, Kliewer SA. Identification of a hormonal basis for gallbladder filling. Nat Med 12: 1253–1255, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coates ME, Gustafsson editors BE. The Germ-free Animal in Biomedical Research. London: Laboratory Animals, 1984, p. 141–213, 291–332. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cong P, Pricolo V, Biancani P, Behar J. Effects of cholesterol on CCK-1 receptors and caveolin-3 proteins recycling in human gallbladder muscle. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 299: G742–G750, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Debray D, Rainteau D, Barbu V, Rouahi M, El Mourabit H, Lerondel S, Rey C, Humbert L, Wendum D, Cottart CH, Dawson P, Chignard N, Housset C. Defects in gallbladder emptying and bile acid homeostasis in mice with cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator deficiencies. Gastroenterology 142: 1581–1591, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ding X, Lu CY, Mei Y, Liu CA, Shi YJ. Correlation between gene expression of CCK-A receptor and emptying dysfunction of the gallbladder in patients with gallstones and diabetes mellitus. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int 4: 295–298, 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Elek G, Rockenbauer A. The free radical signal of pigment gallstones. Klin Wochenschr 60: 33–35, 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Everds NE. Hematology of the laboratory mouse. In: The Mouse in Biomedical Research: Normative Biology, Husbandry, and Models, edited by Fox JG, Barthold SW, Davisson MT, Newcomer CE, Quimby FW, Smith AL. San Diego, CA: Elsevier, 2007, p. 133–170. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feldman M, Feldman M Jr. The incidence of cholelithiasis, cholesterosis, and liver disease in diabetes mellitus: an autopsy study. Diabetes 3: 305–307, 1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fremont-Rahl JJ, Ge Z, Umana C, Whary MT, Taylor NS, Muthupalani S, Carey MC, Fox JG, Maurer KJ. An analysis of the role of the indigenous microbiota in cholesterol gallstone pathogenesis. PLoS One 8: e70657, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Freudenberg F, Broderick AL, Yu BB, Leonard MR, Glickman JN, Carey MC. Pathophysiological basis of liver disease in cystic fibrosis employing a DeltaF508 mouse model. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 294: G1411–G1420, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Freudenberg F, Leonard MR, Liu SA, Glickman JN, Carey MC. Pathophysiological preconditions promoting mixed “black” pigment plus cholesterol gallstones in a DeltaF508 mouse model of cystic fibrosis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 299: G205–G214, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghumman CA, Moutinho AM, Santos A, Tolstogouzov A, Teodoro OM. TOF-SIMS study of cystine and cholesterol stones. J Mass Spectrom 47: 547–551, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gomez-Pinilla PJ, Pozo MJ, Camello PJ. Aging impairs neurogenic contraction in guinea pig urinary bladder: role of oxidative stress and melatonin. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 293: R793–R803, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jacoby RO, Fox JG, Davisson M. Biology and diseases of mice. In: Laboratory Animal Medicine, edited by Fox JG, Anderson LC, Loew FM, Quimby FW. San Diego, CA: Elsevier, 2002, p. 43–44. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Katsika D, Grjibovski A, Einarsson C, Lammert F, Lichtenstein P, Marschall HU. Genetic and environmental influences on symptomatic gallstone disease: a Swedish study of 43,141 twin pairs. Hepatology 41: 1138–1143, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim IS, Myung SJ, Lee SS, Lee SK, Kim MH. Classification and nomenclature of gallstones revisited. Yonsei Med J 44: 561–570, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kline LW, Karpinski E. Progesterone inhibits gallbladder motility through multiple signaling pathways. Steroids 70: 673–679, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lavoie B, Balemba OB, Godfrey C, Watson CA, Vassileva G, Corvera CU, Nelson MT, Mawe GM. Hydrophobic bile salts inhibit gallbladder smooth muscle function via stimulation of GPBAR1 receptors and activation of KATP channels. J Physiol 588: 3295–3305, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]