Abstract

Dysregulation of autophagy, an evolutionarily conserved process for degradation of long-lived proteins and organelles, has been implicated in the pathogenesis of human disease. Recent research has uncovered pathways that control autophagy in the heart and molecular mechanisms by which alterations in this process affect cardiac structure and function. Although initially thought to be a nonselective degradation process, autophagy, as it has become increasingly clear, can exhibit specificity in the degradation of molecules and organelles, such as mitochondria. Furthermore, it has been shown that autophagy is involved in a wide variety of previously unrecognized cellular functions, such as cell death and metabolism. A growing body of evidence suggests that deviation from appropriate levels of autophagy causes cellular dysfunction and death, which in turn leads to heart disease. Here, we review recent advances in understanding the role of autophagy in heart disease, highlight unsolved issues, and discuss the therapeutic potential of modulating autophagy in heart disease.

Keywords: autophagy, mitophagy, protein quality control, autosis

autophagy is an evolutionarily conserved cellular process in which proteins, lipids, and organelles are degraded in lysosomes (42). In most cells, several forms of autophagy operate that differ in the means by which cargo is delivered to the lysosome. In macroautophagy, the form that has been most intensively studied: double membrane vesicles called autophagosomes engulf cytoplasm, protein aggregates, pathogens, and organelles (or parts thereof) and traffic the contents to lysosomes. Cargo selection in macroautophagy is often nonspecific. However, specificity may be conferred in some instances when autophagosome formation is directed to a specific target (e.g., the elimination of defective mitochondria during “mitophagy”). A second form of autophagy, chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA), employs molecular chaperones rather than autophagosomes to move soluble cytoplasmic proteins to lysosomes for degradation. In this form of autophagy, the chaperone binds a specific target sequence on the protein to be eliminated. A third form of autophagy, microautophagy, involves the uptake of cargo directly into lysosomes.

Autophagy plays important roles in baseline cellular homeostasis. Examples include the catabolism of certain long-lived proteins and the elimination of denatured/aggregated proteins and damaged/senescent organelles (cellular “quality control”). Moreover, autophagy is a critical adaptive mechanism. It is markedly augmented in response to a wide variety of cellular stresses and helps cells to cope with these insults. One example is starvation where autophagy-mediated catabolism and recycling of cellular components help cells survive an energetic crisis. In contrast to these adaptive roles, evidence suggests that autophagy may sometimes also play pathological, and even lethal, roles in some cellular contexts (46), although the molecular basis of these maladaptive effects remains poorly understood.

The last decade has witnessed a tremendous growth in research into the physiological and pathological roles, as well as the molecular mechanisms, of autophagy (33). Increasing lines of evidence suggest that besides catabolism and quality control, autophagy is involved in multiple cellular functions, including cell death, defense against pathogens, immunity, and metabolism (42). For example, autophagy degrades lipid droplets, thereby regulating fatty acid metabolism and lipotoxicity (76). In addition, dysregulation of autophagy can contribute to a wide range of human disorders, including heart disease (38, 42, 69). Indeed, the adult heart, which is under continuous mechanical and neurohormonal stress, is particularly dependent on autophagy to maintain normal function. Here we summarize recent topics and unsolved issues in autophagy research in the heart.

Techniques for Quantifying Autophagy

Quantification of autophagy is critical to understanding its adaptive and maladaptive roles. Unfortunately, obtaining accurate information regarding rates of autophagy in the heart is technically challenging. Since almost all work to date in the heart has focused on macroautophagy, our comments will be restricted to this form (which will be referred to simply as “autophagy”), unless otherwise specified. One of the most common misconceptions is the concept that an increased number of autophagosomes indicate increased rates of autophagy (34). The number of autophagosomes is determined by the balance between the rate of generation of autophagosomes and that of their conversion to autolysosomes or degradation in lysosomes. Accordingly, increases in autophagosome number may indicate either enhancement of autophagosome formation or inhibition of the autophagic pathway downstream of autophagosome formation. To know whether autophagic rates are increased, it is essential to distinguish these possibilities by assessing “autophagic flux.” Autophagosome quantity in the heart can be conveniently monitored using green fluorescent protein (GFP)-microtubule-associated protein 1A/1B-light chain 3 (LC3) transgenic mice (55). These mice express a GFP reporter fused to LC3, the only autophagy-related protein located on autophagosomes, either systemically (55) or in a heart-restricted manner (86). Autophagic flux can be evaluated by counting autophagosome number as indicated by GFP-LC3 puncta in the presence or absence of chloroquine, an inhibitor of autophagosome-autolysosome fusion (26). If a given stimulus results in increases in autophagosome number in the presence of chloroquine, then that stimulus is augmenting autophagosome formation or flux. Monomeric red fluorescent protein (mRFP)-GFP-LC3, another LC3 indicator, is convenient in that it allows one to distinguish autolysosomes from autophagosomes (32). This LC3 indicator uses the fact that color emission from GFP, but not mRFP, is quenched at a low pH in autolysosomes. Thus this reporter emits both green and red colors on autophagosomes, whereas it only emits red color on autolysosomes. By quantifying LC3 puncta showing both green and red, indicating autophagosomes, and those showing only red, indicating autolysosomes, one can assess whether conversion from autophagosomes to autolysosomes (i.e., flux) is stimulated. Tandem-fluorescent LC3 mice, which express mRFP-GFP-LC3 in a heart-specific manner, are useful for assessing the extent of autophagic flux in response to stress in the heart (18). Even if the laboratory setting does not allow the use of these indicator mice, one should consider at least the following methods to assess autophagic flux in the heart. The first is to measure the level of autophagic substrates, including p62/SQSTM1 (p62) and GFP-LC3 (34). For example, decreases in p62 protein without changes in p62 mRNA expression or cleavage of GFP from GFP-LC3 may indicate that protein degradation is due to autophagy. It should be noted, however, that accumulation, rather than degradation, of p62 can be observed in some cases, such as when mitochondrial autophagy is stimulated (81). Thus the absence of a decrease in p62 may not necessarily exclude stimulation of autophagy. Measurement of lysosome-dependent, long-lived protein degradation is also useful for evaluating autophagic flux. By the combination of multiple assays, it may be possible to monitor autophagic flux in the heart in a more reliable manner (56).

Quantification of autophagic flux allows one to correlate changes with a given pathological stimulus. However, to establish a cause-and-effect link between changes in autophagic flux and function, it is necessary to perturb autophagic flux. For example, if one finds that autophagy is stimulated in response to a pathological stress on the heart, one could test how the heart reacts in the absence of autophagy. On the other hand, if one finds that autophagy is inhibited, one could examine how the heart reacts when autophagy is rescued. Traditionally, 3-methyladenine is used to inhibit autophagy, whereas rapamycin is used to stimulate autophagy in the heart. However, given the nonspecific autophagy-independent effects associated with these chemicals, the use of more specific interventions directly acting on the autophagic machinery, such as genetic deletion of Atg genes (57) and overexpression of Atg7 (62), both in vitro and in vivo, is desirable. Unfortunately, even if one uses these genetic manipulations, many Atg genes have autophagy-independent functions. Thus the results of the interventions may derive from their autophagy-independent actions. To avoid these limitations, one could employ multiple genetic and/or pharmacological approaches to modulate autophagy and evaluate whether those interventions lead to similar effects. Inclusion of autophagic flux data and mechanistic assessment of the functional significance of changes in autophagic flux is needed to gain a basic understanding of the role of autophagy in the process under consideration. The reader is referred to “Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy” regarding the current standards in autophagy research (34).

Mitophagy and Heart Diseases

Increasing lines of evidence suggest that selective forms of autophagy may operate in an organelle-specific manner, selectively targeting mitochondria (mitophagy), the endoplasmic reticulum (reticulophagy), ribosomes (ribophagy), peroxisomes (pexophagy), and portions of the nucleus (nucleophagy) (60). Among various body tissues, the myocardium contains a particularly high concentration of mitochondria. Whereas these organelles are critical for the production of ATP, when damaged or senescent they pose a risk to the internal cellular environment by virtue of their abilities to produce reactive species and contaminate the mitochondrial pool with mutated DNA. Accordingly, the heart is particularly susceptible to stresses that damage mitochondria, and defective mitochondria must be efficiently removed (24). This takes place both through generalized autophagy (where mitochondria are captured nonspecifically in bulk by autophagosomes) and by mitophagy (a more specialized form of macroautophagy where damaged and senescent mitochondria are specifically targeted for elimination).

Removal of damaged organelles by autophagy can be documented by either immunostaining to show colocalization of organelle-specific markers with LC3 puncta or by direct visualization of the presence of specific organelles within autophagosomes via electron microscopic analyses (22, 39). Lysosomal degradation of mitochondrial proteins can be evaluated using mito-Keima, a fluorescent protein that changes color at acidic pH (29). Although this indicator alone cannot prove that translocation of mitochondrial proteins occurs through mitophagy, inhibition of the translocation by interventions that suppress autophagy or mitophagy would indicate that the mitochondrial clearance is mediated through autophagy or mitophagy (25). Parkin translocation to mitochondria and Parkin-dependent ubiquitination of mitochondrial proteins (see below) are also used to show activation of mitophagy (23, 39). Mitophagy is often accompanied by decreases in mitochondrial inner membrane/matrix proteins and mitochondrial DNA (22, 25). It should be noted, however, that caution should be exercised when interpreting the results obtained from these assays; none of these assays alone can prove the presence of cargo-specific autophagy such as mitophagy, because it is challenging to distinguish cargo-specific autophagy from general autophagy.

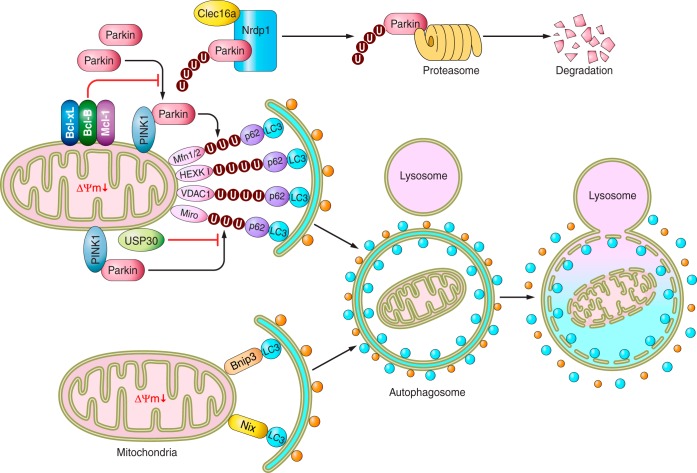

There are two signaling pathways involved in targeting damaged mitochondria to autophagosomes: the phosphatase and tensin homolog-induced putative kinase 1 (PINK1)-Parkin-mediated pathway and the mitophagy receptor-mediated pathway (Fig. 1). PINK1 is a mitochondrially targeted serine/threonine kinase that is degraded by the presenilin-associated rhomboid-like protease under control conditions (27). In damaged mitochondria with depolarized membrane potential, PINK1 is stabilized on the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM), where it then phosphorylates multiple substrates, including the mitochondrial fusion-promoting protein mitofusin 2 (Mfn2) (8). On the other hand, PINK1 is downregulated through posttranscriptional mechanisms in the human end-stage failing heart (4). When phosphorylated, Mfn2 acquires a second function as a mitochondrial receptor for Parkin, an E3 ubiquitin ligase, thereby recruiting Parkin to the OMM (80). PINK1 also phosphorylates Parkin (73) as well as ubiquitin (28, 36). Once Parkin is activated, it promotes ubiquitination of a number of OMM proteins, including Mfn1/2, hexokinase I, voltage-dependent anion-selective channel protein 1, and Miro. The adapter protein p62 next binds to ubiquitinated substrates via its ubiquitin-associated domains and to LC3 on the autophagosomal membrane, thereby resulting in selective engulfment of the damaged mitochondrion by an autophagosome and elimination of that mitochondrion (17). Recently, several endogenous inhibitory mechanisms of PINK1-Parkin-mediated mitophagy have been discovered. Ubiquitin-specific protease 30, a deubiquitinase localized in the OMM, inhibits mitophagy by removing ubiquitin from substrates ubiquitinated by Parkin (6). C-type lectin domain family 16, a membrane-associated endosomal protein and a product of a disease susceptibility gene for type 1 diabetes, multiple sclerosis, and adrenal dysfunction was also found to be a novel negative regulator of PINK1-Parkin-mediated mitophagy (77). C-type lectin domain family 16 physically interacts with neuregulin receptor degradation protein 1, an E3 ubiquitin ligase, thereby promoting proteasomal degradation of Parkin, which in turn inhibits mitophagy. Antiapoptotic B-cell lymphoma-2 (BCL-2) family proteins, including B-cell lymphoma-extra large (BCL-xL), myeloid cell leukemia 1, and BCL-2, on the OMM inhibit mitophagy through inhibition of Parkin translocation to depolarized mitochondria in a Beclin-1-independent manner (20). The tumor suppressor p53 also inhibits mitophagy by sequestering Parkin in the cytosol in the mouse heart (22).

Fig. 1.

Schematic model of the molecular mechanisms regulating mitophagy. There are 2 signaling pathways for selective activation of mitophagy: the phosphatase and tensin homolog-induced putative kinase 1 (PINK1)-Parkin-mediated pathway and the mitophagic-receptor [Bcl-2/adenovirus E1B 19 kDa-interacting protein 3 (BNIP3) and BNIP-like (NIX)]-mediated pathway (see text for details and definitions of abbreviations). There are also several systems for suppression of mitophagy. Arrows denote stimulation, and T-shaped indicators denote inhibition. U, ubiquitin; ΔΨm, mitochondrial membrane potential.

Several previous studies suggest that PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy may play a protective role in the heart. A significant increase in mortality and infarct size is observed in Parkin−/− mice compared with wild-type mice 7 days after myocardial infarction (MI) (37). Conversely, overexpression of Parkin inhibits hypoxia-induced acute cell death in adult rat cardiomyocytes in vitro (26). Similarly, the infarct size after ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) is significantly greater in the hearts of PINK1−/− mice than in wild-type mice in an ex vivo model, and overexpression of PINK1 protects against simulated I/R-mediated cell death in HL-1 cardiac cells (75). Furthermore, the hearts of PINK1−/− mice exhibit ventricular dysfunction and hypertrophy with increased fibrosis, apoptosis, oxidative stress, and reduced mitochondrial respiration at 2 mo of age (4, 75). Whether PINK1 and Parkin function exclusively through mitophagy remains to be clarified. The role of PINK1 and Parkin in mitochondrial autophagy and mitophagy has been primarily investigated using stimuli inducing mitochondrial depolarization, such as cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone. Whether similar mechanisms mediate the removal of damaged mitochondria through mitophagy in response to more pathologically relevant stimuli, such as I/R and hemodynamic stress, remains to be elucidated.

Damaged mitochondria are also recognized by autophagosomes through Bcl-2/adenovirus E1B 19 kDa-interacting protein 3 (BNIP3) and BNIP3 like (NIX), proapoptotic Bcl-2 homology 3-only family proteins (65, 85). In addition to their cell death functions, these OMM proteins also bind to LC3 on the autophagosome, which, in turn, mediates mitophagy. Ablation of NIX expression results in progressive cardiac dysfunction with age as a consequence of the accumulation of impaired mitochondria (14). The fact that hearts of NIX−/− BNIP3−/− double-knockout mice demonstrate accelerated cardiac hypertrophy and mitochondrial dysfunction compared with the single NIX−/− and BNIP3−/− mice indicates that Nix and Bnip3 have nonoverlapping functions (14). Further investigation is required to elucidate the roles of NIX and BNIP3 in mediating mitophagy in the heart in vivo. Recently, other mitochondrial proteins and lipids, including FUN14 domain containing 1 and cardiolipin, have been found to act as receptors for LC3 and participate in mitophagy (11, 45); their roles in mitophagy in the heart remain to be elucidated.

When mitochondria are degraded by autophagy, lysosomal DNase II digests mitochondrial DNA released from damaged mitochondria. However, as mitochondrial DNA contains inflammatogenic unmethylated CpG motifs, mitochondrial DNA that escapes degradation by autophagy promotes inflammation in a Toll-like-receptor 9-dependent manner in cardiomyocytes, which in turn causes chronic inflammation in failing hearts (59). Thus coordination between autophagy and lysosomes appears essential to prevent a myocardial inflammatory response caused by mitochondrial DNA.

Removal of damaged mitochondria by autophagy appears coupled to mitochondrial fission, a process that asymmetrically divides mitochondria into two fragments. The smaller mitochondrial fragment generated by fission is often depolarized and susceptible to being engulfed by autophagosomes. Mitochondrial fission is regulated by the recruitment of dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1), a cytoplasmic GTPase, to mitochondrial fission sites in the OMM in coordination with mitochondrial fission 1 and mitochondrial fission factor (64). In contrast, mitochondrial fusion is regulated by Mfn1 and Mfn2, also on the OMM (40). A lack of mitochondrial fusion due to downregulation of Mfn1 and Mfn2 promotes cardiac dysfunction at baseline and in response to stress (9). In contrast, suppression of mitochondrial fission by inhibition of Drp1 with mitochondrial division inhibitor-1, a chemical inhibitor of Drp1, results in reduction of infarction size in response to I/R (61). Similarly, inhibition of Drp1 with mitochondrial division inhibitor-1 or knockdown by Drp1 RNAi prevents cardiomyocyte death after hypoxia/reoxygenation (71). However, inhibition of mitochondrial fission using fission 1 RNAi or dominant-negative Drp1 mutant (Drp1K38A) results in suppression of mitophagy, accumulation of damaged mitochondrial proteins, and reduced respiration, thereby leading to metabolic dysfunction in pancreatic INS1 cells (79), suggesting that mitochondrial fission is also essential for cell survival. Cardiac specific-heterozygous deletion of Drp1 exacerbated myocardial injury in response to I/R (25). Thus mitochondrial fission appears to affect cell survival both positively and negatively in a context-dependent manner.

It should be noted that many conclusions regarding the role of fission and fusion in regulating mitochondrial functions and autophagy have been obtained in non-cardiac cells. Although the function of fission and fusion in the heart has been deduced primarily from genetic studies, the occurrence of fission and fusion has not been demonstrated in an unequivocal manner in adult ventricular cardiomyocytes. In addition, although electron microscopic analyses allow observation of autophagosomes containing mitochondria in the heart and the cardiomyocytes therein, whether they reflect degradation of mitochondria by general autophagy or mitophagy that selectively degrades mitochondria, remains to be elucidated. Furthermore, since many interventions simultaneously affect mitochondrial morphology and autophagy, it is challenging to separate the effect of fission and fusion from that of mitochondrial autophagy alone. Thus careful observation of mitochondrial morphology as well as molecular interventions to distinguish the effect of fission and fusion from that of mitochondrial autophagy are needed to better understand the precise role of these mitochondrial quality control mechanisms in the heart.

Protein Toxicity in Heart Diseases and Autophagy

As the endogenous proliferative capacity of mammalian adult cardiomyocytes is limited, vigorous systems for maintaining protein quality control (PQC) are essential to sustain the long-term well-being of cardiomyocytes. In addition to various protein refolding mechanisms (7), PQC is maintained through degradation via the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) (44) and autophagy (3). Impairment of autophagy causes aggregation of damaged and/or misfolded proteins in cardiomyocytes, thereby damaging the cell and potentially leading to cell death. Suppression of constitutive autophagy by genetic deletion of Atg5 leads to cardiac dysfunction with increased protein aggregation in the heart (57). Desmin-related cardiomyopathies (DRCs), cardiomyopathies caused by inherited or de novo mutations in desmin and accessory proteins, are typified by severe and progressive forms of heart failure. Impairment of interaction between desmin and αB-crystallin (CryAB), a small heat shock protein that functions as a molecular chaperone, causes protein aggregation and myofibrillar disarray, thereby leading to severe cardiac dysfunction. Bhuiyan et al. (3) found that enhanced levels of autophagy ameliorate DRC by crossing CryABR120G mice, a model of DRC, and cardiac-specific atg7 transgenic mice (3). Accumulation of protein aggregates and ubiquitinated proteins is also seen in cardiomyocytes from hearts with pressure overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy, chronic MI, and dilated cardiomyopathy (49, 78). We have recently shown that aggresomes colocalized with p62 accumulate markedly in cardiomyocytes from chronic MI hearts (49).

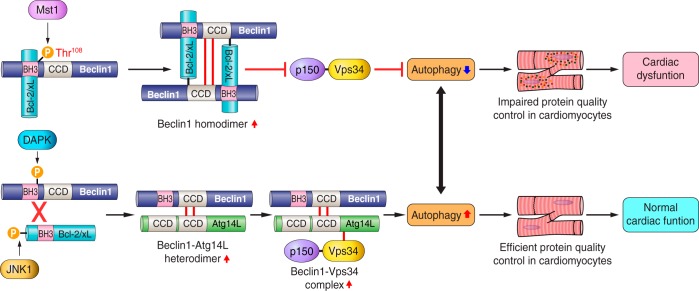

What is the cause of protein aggregation in the heart during stress? Mammalian sterile 20-like kinase 1 (Mst1) is a proapoptotic serine/threonine kinase that is activated in response to stress, including volume overload during cardiac remodeling. Mst1 phosphorylates Thr108 of Beclin-1, enhances the interaction between Beclin-1 and Bcl-2/Bcl-xL, and induces Beclin-1 homodimer formation (Fig. 2). In this condition, Beclin-1 cannot activate class III phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, and thus autophagy is suppressed (84). Increased phosphorylation of Beclin-1 by Mst1, inhibition of autophagy, and increased accumulation of aggresomes are also seen in hearts in human end-stage dilated cardiomyopathy. These results suggest that Mst1 may be one of the endogenous facilitators of protein aggregation in the stressed heart. It has been recently shown that overexpression of Tollip, a new class of ubiquitin-binding coupling of ubiquitin conjugation to ER degradation-domain protein, causes clearing of Huntington's disease-linked poly Q proteins by autophagy (47). Whether endogenous Tollip regulates aggresome formation in the heart is currently unknown.

Fig. 2.

Schematic model of Beclin-1, B-cell lymphoma-extra large (Bcl-2/xL), and mammalian sterile 20-like kinase 1 (Mst1) interactions in the regulation of autophagy in the heart. Mst1 phosphorylates Beclin-1 at Thr108, leading to enhancement of Beclin-1-Bcl-2/xL binding, Beclin-1 homodimer formation, and inhibition of vacuolar protein sorting 34 (Vps34) kinase activity, thereby suppressing autophagosome formation. Activation of Mst1 downregulates autophagy below physiological levels and suppresses protein quality control, contributing to cardiac dysfunction (see text for details and definitions of abbreviations). Arrows denote stimulation, and T-shaped indicators denote inhibition. P, phosphate; CCD, coiled coil domain; DAPK, death-associated protein kinase.

Can Autophagy Induce Cell Death?

Despite its clearly demonstrated role as an adaptive/survival process, accumulating evidence suggests that, in certain contexts, autophagy may induce cell death. The initial data were merely associative: the presence of autophagic vacuoles in some dying cells (43). But, these observations were unable to differentiate between the possibilities that autophagy was promoting cell death or attempting to rescue the cell. Some insight into the ordering of events has been provided by studies in which autophagy has been genetically manipulated during a pathological process. For example, cardiomyocyte death and pathological remodeling during I/R and pressure overload in the heart can be reduced by inhibiting the induction of autophagy that takes place in these conditions by depletion of Beclin-1, an autophagy gene that is often upregulated in response to oxidative stress (18) and is involved in autophagosome formation through activation of class III phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (54, 86). Autophagy suppression through genetic inhibition has also been shown to alleviate tissue damage in other systems including cerebral I/R, neurodegenerative disease, and liver injury (1, 35). Conversely, induction of autophagy can promote caspase-independent cell death in apoptosis-competent cells (15, 66). Taken together, these observations suggest the possibility that autophagy can induce cell death in some contexts. However, the determinants of whether autophagy results in cell survival or death, and the underlying mechanism of autophagy-related cell death, remain poorly understood.

Liu Y et al. (46) recently showed that increased levels of autophagy in response to Tat-Beclin-1, a cell-penetrating, autophagy-inducing peptide, induce cell death. This cell death, termed “autosis,” has unique morphological characteristics that are distinct from those of either apoptosis or necroptosis, including increased numbers of autophagosomes/autolysosomes, nuclear convolution at early stages, and focal swelling of the perinuclear space at late stages. Autosis is observed in hippocampal neurons of neonatal rats subjected to cerebral hypoxia-ischemia in vivo. Through a chemical screen, this unique form of autophagy-dependent cell death was found to be suppressed effectively by cardiac glycosides, antagonists of Na+/K+-ATPase (46). The molecular mechanisms connecting autophagy, the Na+/K+-ATPase, and cell death remain to be elucidated. Interestingly, however, cardiac glycosides attenuate autotic cell death in vivo. At present, we do not know whether autosis is observed in the heart under conditions in which autophagy has been shown to be detrimental, such as I/R (18, 53) and acute pressure overload (86). If autosis exists in the heart, it would be interesting to test whether cardiac glycosides offer protection against such insults.

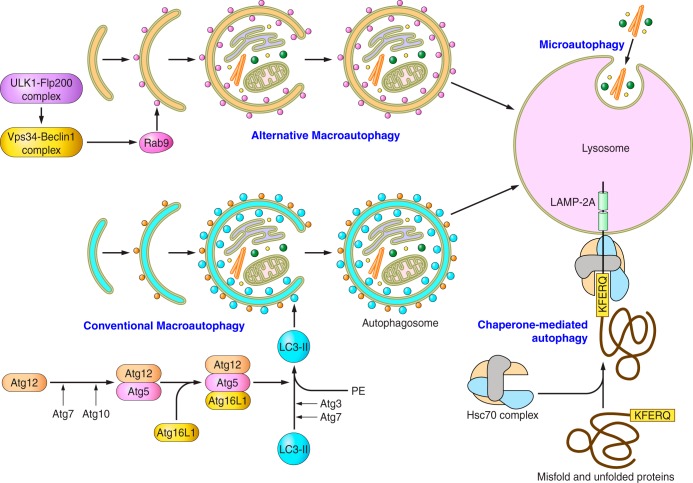

CMA and alternative autophagy

In contrast to macroautophagy, CMA (30) has been studied to only a limited extent in the heart (Fig. 3). The targets of this form of autophagy are specific soluble cytoplasmic proteins that contain a Lys-Phe-Glu-Arg-Gln (KFERQ)-like motif, although the precise sequence can vary (13). CMA substrates are transported to the lysosome in complex with the chaperone heat shock cognate 71-kDa protein, which binds the KFERQ-like motif, rather than in autophagic vacuoles (10). The complex interacts with the lysosomal membrane protein lysosome-associated membrane protein 2A (LAMP-2A), the specific alternatively spliced Lamp2 isoform that mediates CMA (12). Following unfolding (68), the substrate is imported into the lysosome for degradation. An estimated ∼30% of cytosolic proteins possess KFERQ-like sequences (13) and are, therefore, potential CMA substrates, although which actually undergo CMA remains to be determined for each cell type. Interestingly, the ryanodine receptor 2, a sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-release channel that plays critical roles in excitation-contraction in cardiomyocytes, was recently reported to possess multiple KFERQ-like motifs and to be degraded, in part, through CMA (63). Although the role of CMA in cardiac biology has yet to be defined, early studies showed that starvation induces marked reductions of proteins with KFERQ motifs in heart, but not in soleus or extensor digitorum longus muscles, in vivo (82). In the liver, where it has been studied, protein loss by macroautophagy and CMA exhibit distinct kinetics with CMA being delayed. Until recently, little was known about the specific role of CMA in physiological processes in vivo. However, using mice with conditional deletion of LAMP-2A, which exhibit selective downregulation of CMA but not macroautophagy, Schneider et al. (70) found that hepatocyte-specific blockage of CMA induces hepatic glycogen depletion and liver steatosis. Interestingly, the mechanism involved coordinates increases in the levels of enzymes involved in carbohydrate and lipid metabolism resulting from inhibition of CMA. This work demonstrates a role of role for CMA in regulating metabolism in vivo.

Fig. 3.

Schematic model of the major pathways in the regulation of the autophagic machinery. There are 3 different types of autophagic pathways: macroautophagy, microautophagy, and chaperone-mediated autophagy. In macroautophagy, there are 2 subtypes of autophagic pathways: conventional and alternative macroautophagy (see text for details and definitions of abbreviations). ULK1, unc-51-like autophagy-activating kinase 1; Flp-200, FAK family-interacting protein of 200 kDa; Rab9, Rab family GTPase 9; PE, phosphatidylethanolamine.

Macroautophagy is separated into several specific steps, including induction, recognition and selection of cytoplasmic substrates, formation of the autophagosome around substrates, autophagosome-lysosome fusion, degradation of the autolysosomal contents, and release of the degraded products into the cytoplasm. The canonical, or conventional, autophagic pathway consists of evolutionarily conserved signaling molecules encoded by Atgs, including Atg4, Atg5, Beclin-1 (Atg6), Atg7, Atg12, and Atg16, which govern these steps. On the other hand, accumulating lines of evidence suggest that noncanonical autophagic pathways are present. Nishida et al. (58) revealed that Atg5−/−Atg7−/− double-knockout cells are still able to form autophagosomes and degrade autophagic substrates inside the autolysosomes in response to certain stimuli. During the process of this Atg5/Atg7-independent autophagy, termed “alternative autophagy,” the lipidation of LC3 does not occur. Instead, Rab9, a small GTPase involved in membrane trafficking and fusion between the trans-Golgi network and late endosomes, plays a critical role in generating autophagosomes in the alternative autophagic pathway by promoting fusion of the phagophore with vesicles derived from the trans-Golgi network and late endosomes. Recently, Honda S et al. (21) revealed that ULK1-dependent, Atg5-independent macroautophagy is the dominant process for removing mitochondria from reticulocytes in the final stage of erythrocyte maturation. However, the functional significance of alternative autophagy has not yet been demonstrated in the heart.

Autophagy as a Therapeutic Target for Heart Diseases?

Several clinical trials targeting autophagy have been undertaken to treat cancers (52), α1-antitrypsin deficiency liver cirrhosis (19), and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (16). To our knowledge, clinical trials modulating autophagy have not yet been undertaken for heart disease yet. Recently, a novel agent to induce autophagy was developed. Tat-Beclin-1, a peptide derived from an evolutionarily conserved domain of Beclin-1 (267–284) binding with human immunodeficiency virus-1 Nef, strongly induces autophagy by interacting with Golgi-associated plant pathogenesis-related protein 1, a newly identified negative regulator of autophagy (74). Tat-Beclin-1 attenuates the accumulation of polyglutamine expansion protein aggregates (htt103Q) derived from human mutant Huntingtin protein and the replication of several pathogens in vitro and in vivo. Since the efficacy of Tat-Beclin-1 to induce autophagy is potent, it may normalize the level of autophagy in chronic MI hearts where autophagy is suppressed below physiological levels. Further studies are required to test whether Tat-Beclin-1 improves cardiac function in the chronic MI heart. Suppression of histone deacetylases by trichostatin A and suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid, a drug approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, also stimulates autophagy in the heart and the cardiomyocytes therein and attenuates myocardial injury in response to I/R (83).

Mariño et al. (50) recently discovered a mechanism of autophagy regulation by cytosolic acetyl-coenzyme A (AcCoA), a principal integrator referred to as the “hub of metabolism.” Starvation rapidly stimulates rapid depletion of AcCoA, thereby suppressing the activity of the EP300, an acetyltransferase and endogenous negative regulator of autophagy, which, in turn, activates autophagy. Consistently, pharmacological inhibition of EP300 by c646 effectively induced autophagy in mice. Furthermore, maintenance of high AcCoA levels by supplementation of dimethyl-α-ketoglutarate, a cell-permeant precursor of α-ketoglutarate, suppressed maladaptive autophagy induced by pressure overload in the heart. Thus these results suggest that pharmacological strategies targeting AcCoA may allow for novel therapeutic manipulation of autophagy as well.

Although here we discussed Tat-Beclin-1 and AcCoA as examples of interventions to stimulate or inhibit autophagy, respectively, whether autophagy is stimulated or inhibited varies substantially depending on the nature of stress and the timing/stage of disease. Further studies are required to address these issues.

Perspectives

Increasing lines of evidence suggest that suppression of autophagy below physiological levels disrupts the PQC system in cells, thereby inducing chronic heart failure (49, 57). Conversely, excessive induction of autophagy beyond a physiological range may cause cell death, thereby aggravating cardiac function (54, 86). Thus maintaining autophagy at physiological levels appears indispensable for normal cellular homeostasis (41). If this hypothesis is true, assessment of the current level of autophagy is essential. To this end, development of convenient and noninvasive methods to evaluate the level of autophagic flux in vivo is urgently needed.

Recent evidence suggests that autophagy is involved in the degradation of specific proteins or organelles (67). As selective autophagy is mediated by LC3 receptors, including p62 and neighbor of breast cancer 1 gene 1 or ubiquitin-Atg8 adaptors celled Cue5/Tollip adaptors proteins (47), it is possible that autophagy has the potential to degrade specific proteins. Although autophagy may promote survival of energy-starved cardiomyocytes by promoting general catabolism, degradation of specific molecules may also play important roles in mediating cell survival. Identifying individual proteins degraded by autophagy should allow us to identify novel functions of autophagy in cardiomyocytes.

Although we did not discuss them in detail in this review, mechanisms mediating lysosomal degradation, the second half of the autophagic flux, are also likely to be affected in heart diseases and would require further investigation (72). For example, transcription factor EB is a basic helix-loop-helix leucine zipper transcription factor regulating genes involved in lysosomal biogenesis and its activity is regulated by phosphorylation by mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1, ERK, and PKC (48, 51). We have recently shown that the combined loss of Ras-related GTP binding A and B GTPases, key components of a lysosome-based signaling system (2), in cardiomyocytes induces cardiomyopathy mimicking lysosomal storage disease. In these mice, lysosomal acidification is severely compromised because of a decreased vacuolar-type H(+)-ATPase level in the lysosomal fraction, suggesting that Ras-related GTP binding A and B play important roles in regulating the lysosomal function in the heart (31). Further investigations are required to elucidate how autophagy is regulated by these endogenous regulators during stress in the heart.

In summary, autophagy critically controls survival and death of cardiomyocytes during cardiac stress and heart failure. The study of autophagy in the heart is hampered by the technical difficulty of correctly assessing autophagic flux and the lack of interventions selectively modulating the activity of autophagy in the heart. Despite these challenges, modulation of autophagy has therapeutic potential in the context of heart diseases, and thus better understanding of autophagy is essential. Judging from the fundamental importance of autophagy in survival and death of cardiomyocytes, our effort should lead to the discovery of a new modality for the treatment of heart disease in the near future.

GRANTS

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants HL-87023, HL-101217, and HL-85577 (to A. B. Gustafsson); HL-60665 and CA-170911 (to R. N. Kitsis); and HL-67724, HL-91469, HL-102738, HL-112330, and AG-23039 (to J. Sadoshima). This work was also supported by the Fondation Leducq Transatlantic Networks of Excellence (to J. Sadoshima), Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) 26461126 (to Y. Maejima), American Heart Association Scientist Development Grant 12SDG12070262 (to Y. Maejima), American Heart Association Established Investigator Award 14EIA18970095 (to A. B. Gustafsson), and Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI Grant-in-Aid for Exploratory Research 26670399 (to M. Isobe).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Y.M., Y.C., R.N.K., and J.S. drafted manuscript; Y.M., Y.C., M.I., A.B.G., R.N.K., and J.S. approved final version of manuscript; A.B.G., R.N.K., and J.S. edited and revised manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Christopher Brady and Daniela Zablocki for critical reading of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baehrecke EH. Autophagy: dual roles in life and death? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 6: 505–510, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bar-Peled L, Sabatini DM. Regulation of mTORC1 by amino acids. Trends Cell Biol 24: 400–406, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhuiyan MS, Pattison JS, Osinska H, James J, Gulick J, McLendon PM, Hill JA, Sadoshima J, Robbins J. Enhanced autophagy ameliorates cardiac proteinopathy. J Clin Invest 123: 5284–5297, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Billia F, Hauck L, Konecny F, Rao V, Shen J, Mak TW. PTEN-inducible kinase 1 (PINK1)/Park6 is indispensable for normal heart function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 9572–9577, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bingol B, Tea JS, Phu L, Reichelt M, Bakalarski CE, Song Q, Foreman O, Kirkpatrick DS, Sheng M. The mitochondrial deubiquitinase USP30 opposes parkin-mediated mitophagy. Nature 510: 370–375, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen B, Retzlaff M, Roos T, Frydman J. Cellular strategies of protein quality control. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 3: a004374, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen Y, Dorn GW 2nd. PINK1-phosphorylated mitofusin 2 is a Parkin receptor for culling damaged mitochondria. Science 340: 471–475, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen Y, Liu Y, Dorn GW 2nd. Mitochondrial fusion is essential for organelle function and cardiac homeostasis. Circ Res 109: 1327–1331, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiang HL, Terlecky SR, Plant CP, Dice JF. A role for a 70-kilodalton heat shock protein in lysosomal degradation of intracellular proteins. Science 246: 382–385, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chu CT, Ji J, Dagda RK, Jiang JF, Tyurina YY, Kapralov AA, Tyurin VA, Yanamala N, Shrivastava IH, Mohammadyani D, Qiang Wang KZ, Zhu J, Klein-Seetharaman J, Balasubramanian K, Amoscato AA, Borisenko G, Huang Z, Gusdon AM, Cheikhi A, Steer EK, Wang R, Baty C, Watkins S, Bahar I, Bayir H, Kagan VE. Cardiolipin externalization to the outer mitochondrial membrane acts as an elimination signal for mitophagy in neuronal cells. Nat Cell Biol 15: 1197–1205, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cuervo AM, Dice JF. A receptor for the selective uptake and degradation of proteins by lysosomes. Science 273: 501–503, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dice JF. Peptide sequences that target cytosolic proteins for lysosomal proteolysis. Trends Biochem Sci 15: 305–309, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dorn GW., 2nd Mitochondrial pruning by Nix and BNip3: an essential function for cardiac-expressed death factors. J Cardiovasc Transl Res 3: 374–383, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elgendy M, Sheridan C, Brumatti G, Martin SJ. Oncogenic Ras-induced expression of Noxa and Beclin-1 promotes autophagic cell death and limits clonogenic survival. Mol Cell 42: 23–35, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fornai F, Longone P, Cafaro L, Kastsiuchenka O, Ferrucci M, Manca ML, Lazzeri G, Spalloni A, Bellio N, Lenzi P, Modugno N, Siciliano G, Isidoro C, Murri L, Ruggieri S, Paparelli A. Lithium delays progression of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 2052–2057, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geisler S, Holmstrom KM, Skujat D, Fiesel FC, Rothfuss OC, Kahle PJ, Springer W. PINK1/Parkin-mediated mitophagy is dependent on VDAC1 and p62/SQSTM1. Nat Cell Biol 12: 119–131, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hariharan N, Zhai P, Sadoshima J. Oxidative stress stimulates autophagic flux during ischemia/reperfusion. Antioxid Redox Signal 14: 2179–2190, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hidvegi T, Ewing M, Hale P, Dippold C, Beckett C, Kemp C, Maurice N, Mukherjee A, Goldbach C, Watkins S, Michalopoulos G, Perlmutter DH. An autophagy-enhancing drug promotes degradation of mutant alpha1-antitrypsin Z and reduces hepatic fibrosis. Science 329: 229–232, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hollville E, Carroll RG, Cullen SP, Martin SJ. Bcl-2 family proteins participate in mitochondrial quality control by regulating Parkin/PINK1-dependent mitophagy. Mol Cell 55: 451–466, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Honda S, Arakawa S, Nishida Y, Yamaguchi H, Ishii E, Shimizu S. Ulk1-mediated Atg5-independent macroautophagy mediates elimination of mitochondria from embryonic reticulocytes. Nat Commun 5: 4004, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hoshino A, Mita Y, Okawa Y, Ariyoshi M, Iwai-Kanai E, Ueyama T, Ikeda K, Ogata T, Matoba S. Cytosolic p53 inhibits Parkin-mediated mitophagy and promotes mitochondrial dysfunction in the mouse heart. Nat Commun 4: 2308, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huang C, Andres AM, Ratliff EP, Hernandez G, Lee P, Gottlieb RA. Preconditioning involves selective mitophagy mediated by Parkin and p62/SQSTM1. PLoS One 6: e20975, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ikeda Y, Sciarretta S, Nagarajan N, Rubattu S, Volpe M, Frati G, Sadoshima J. New insights into the role of mitochondrial dynamics and autophagy during oxidative stress and aging in the heart. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2014: 210934, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ikeda Y, Shirakabe A, Maejima Y, Zhai P, Sciarretta S, Toli J, Nomura M, Mihara K, Egashira K, Ohishi M, Abdellatif M, Sadoshima J. Endogenous Drp1 mediates mitochondrial autophagy and protects the heart against energy stress. Circ Res 2014 Oct 20. pii: CIRCRESAHA.114.303356. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Iwai-Kanai E, Yuan H, Huang C, Sayen MR, Perry-Garza CN, Kim L, Gottlieb RA. A method to measure cardiac autophagic flux in vivo. Autophagy 4: 322–329, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jin SM, Lazarou M, Wang C, Kane LA, Narendra DP, Youle RJ. Mitochondrial membrane potential regulates PINK1 import and proteolytic destabilization by PARL. J Cell Biol 191: 933–942, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kane LA, Lazarou M, Fogel AI, Li Y, Yamano K, Sarraf SA, Banerjee S, Youle RJ. PINK1 phosphorylates ubiquitin to activate Parkin E3 ubiquitin ligase activity. J Cell Biol 205: 143–153, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Katayama H, Kogure T, Mizushima N, Yoshimori T, Miyawaki A. A sensitive and quantitative technique for detecting autophagic events based on lysosomal delivery. Chem Biol 18: 1042–1052, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaushik S, Bandyopadhyay U, Sridhar S, Kiffin R, Martinez-Vicente M, Kon M, Orenstein SJ, Wong E, Cuervo AM. Chaperone-mediated autophagy at a glance. J Cell Sci 124: 495–499, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim YC, Park HW, Sciarretta S, Mo JS, Jewell JL, Russell RC, Wu X, Sadoshima J, Guan KL. Rag GTPases are cardioprotective by regulating lysosomal function. Nat Commun 5: 4241, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kimura S, Noda T, Yoshimori T. Dissection of the autophagosome maturation process by a novel reporter protein, tandem fluorescent-tagged LC3. Autophagy 3: 452–460, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Klionsky DJ. Autophagy: from phenomenology to molecular understanding in less than a decade. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 8: 931–937, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klionsky DJ. Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy. Autophagy 8: 445–544, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koike M, Shibata M, Tadakoshi M, Gotoh K, Komatsu M, Waguri S, Kawahara N, Kuida K, Nagata S, Kominami E, Tanaka K, Uchiyama Y. Inhibition of autophagy prevents hippocampal pyramidal neuron death after hypoxic-ischemic injury. Am J Pathol 172: 454–469, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koyano F, Okatsu K, Kosako H, Tamura Y, Go E, Kimura M, Kimura Y, Tsuchiya H, Yoshihara H, Hirokawa T, Endo T, Fon EA, Trempe JF, Saeki Y, Tanaka K, Matsuda N. Ubiquitin is phosphorylated by PINK1 to activate parkin. Nature 510: 162–166, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kubli DA, Zhang X, Lee Y, Hanna RA, Quinsay MN, Nguyen CK, Jimenez R, Petrosyan S, Murphy AN, Gustafsson AB. Parkin protein deficiency exacerbates cardiac injury and reduces survival following myocardial infarction. J Biol Chem 288: 915–926, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lavandero S, Troncoso R, Rothermel BA, Martinet W, Sadoshima J, Hill JA. Cardiovascular autophagy: concepts, controversies, and perspectives. Autophagy 9: 1455–1466, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee Y, Lee HY, Hanna RA, Gustafsson AB. Mitochondrial autophagy by Bnip3 involves Drp1-mediated mitochondrial fission and recruitment of Parkin in cardiac myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 301: H1924–H1931, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Legros F, Lombes A, Frachon P, Rojo M. Mitochondrial fusion in human cells is efficient, requires the inner membrane potential, and is mediated by mitofusins. Mol Biol Cell 13: 4343–4354, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Levine B. Cell biology: autophagy and cancer. Nature 446: 745–747, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Levine B, Kroemer G. Autophagy in the pathogenesis of disease. Cell 132: 27–42, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Levine B, Yuan J. Autophagy in cell death: an innocent convict? J Clin Invest 115: 2679–2688, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li J, Horak KM, Su H, Sanbe A, Robbins J, Wang X. Enhancement of proteasomal function protects against cardiac proteinopathy and ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice. J Clin Invest 121: 3689–3700, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liu L, Feng D, Chen G, Chen M, Zheng Q, Song P, Ma Q, Zhu C, Wang R, Qi W, Huang L, Xue P, Li B, Wang X, Jin H, Wang J, Yang F, Liu P, Zhu Y, Sui S, Chen Q. Mitochondrial outer-membrane protein FUNDC1 mediates hypoxia-induced mitophagy in mammalian cells. Nat Cell Biol 14: 177–185, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu Y, Shoji-Kawata S, Sumpter RM Jr, Wei Y, Ginet V, Zhang L, Posner B, Tran KA, Green DR, Xavier RJ, Shaw SY, Clarke PG, Puyal J, Levine B. Autosis is a Na+,K+-ATPase-regulated form of cell death triggered by autophagy-inducing peptides, starvation, and hypoxia-ischemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 20364–20371, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lu K, Psakhye I, Jentsch S. Autophagic clearance of polyQ proteins mediated by ubiquitin-Atg8 adaptors of the conserved CUET protein family. Cell 158: 549–563, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ma AD, Metjian A, Bagrodia S, Taylor S, Abrams CS. Cytoskeletal reorganization by G protein-coupled receptors is dependent on phosphoinositide 3-kinase gamma, a Rac guanosine exchange factor, and Rac. Mol Cell Biol 18: 4744–4751, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maejima Y, Kyoi S, Zhai P, Liu T, Li H, Ivessa A, Sciarretta S, Del Re DP, Zablocki DK, Hsu CP, Lim DS, Isobe M, Sadoshima J. Mst1 inhibits autophagy by promoting Beclin1-Bcl-2 interaction. Nat Med 19: 1478–1488, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marino G, Pietrocola F, Eisenberg T, Kong Y, Malik SA, Andryushkova A, Schroeder S, Pendl T, Harger A, Niso-Santano M, Zamzami N, Scoazec M, Durand S, Enot DP, Fernandez AF, Martins I, Kepp O, Senovilla L, Bauvy C, Morselli E, Vacchelli E, Bennetzen M, Magnes C, Sinner F, Pieber T, Lopez-Otin C, Maiuri MC, Codogno P, Andersen JS, Hill JA, Madeo F, Kroemer G. Regulation of autophagy by cytosolic acetyl-coenzyme A. Mol Cell 53: 710–725, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Martina JA, Chen Y, Gucek M, Puertollano R. MTORC1 functions as a transcriptional regulator of autophagy by preventing nuclear transport of TFEB. Autophagy 8: 903–914, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Pavlides S, Whitaker-Menezes D, Daumer KM, Milliman JN, Chiavarina B, Migneco G, Witkiewicz AK, Martinez-Cantarin MP, Flomenberg N, Howell A, Pestell RG, Lisanti MP, Sotgia F. Tumor cells induce the cancer associated fibroblast phenotype via caveolin-1 degradation: implications for breast cancer and DCIS therapy with autophagy inhibitors. Cell Cycle 9: 2423–2433, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Matsui M, Oshima M, Oshima H, Takaku K, Maruyama T, Yodoi J, Taketo MM. Early embryonic lethality caused by targeted disruption of the mouse thioredoxin gene. Dev Biol 178: 179–185, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Matsui Y, Takagi H, Qu X, Abdellatif M, Sakoda H, Asano T, Levine B, Sadoshima J. Distinct roles of autophagy in the heart during ischemia and reperfusion. Roles of AMP-activated protein kinase and beclin 1 in mediating autophagy. Circ Res 100: 914–922, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mizushima N, Yamamoto A, Matsui M, Yoshimori T, Ohsumi Y. In vivo analysis of autophagy in response to nutrient starvation using transgenic mice expressing a fluorescent autophagosome marker. Mol Biol Cell 15: 1101–1111, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mizushima N, Yoshimori T, Levine B. Methods in mammalian autophagy research. Cell 140: 313–326, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nakai A, Yamaguchi O, Takeda T, Higuchi Y, Hikoso S, Taniike M, Omiya S, Mizote I, Matsumura Y, Asahi M, Nishida K, Hori M, Mizushima N, Otsu K. The role of autophagy in cardiomyocytes in the basal state and in response to hemodynamic stress. Nat Med 13: 619–624, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Nishida Y, Arakawa S, Fujitani K, Yamaguchi H, Mizuta T, Kanaseki T, Komatsu M, Otsu K, Tsujimoto Y, Shimizu S. Discovery of Atg5/Atg7-independent alternative macroautophagy. Nature 461: 654–658, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Oka T, Hikoso S, Yamaguchi O, Taneike M, Takeda T, Tamai T, Oyabu J, Murakawa T, Nakayama H, Nishida K, Akira S, Yamamoto A, Komuro I, Otsu K. Mitochondrial DNA that escapes from autophagy causes inflammation and heart failure. Nature 485: 251–255, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Okamoto K. Organellophagy: eliminating cellular building blocks via selective autophagy. J Cell Biol 205: 435–445, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ong SB, Subrayan S, Lim SY, Yellon DM, Davidson SM, Hausenloy DJ. Inhibiting mitochondrial fission protects the heart against ischemia/reperfusion injury. Circulation 121: 2012–2022, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pattison JS, Osinska H, Robbins J. Atg7 induces basal autophagy and rescues autophagic deficiency in CryABR120G cardiomyocytes. Circ Res 109: 151–160, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pedrozo Z, Torrealba N, Fernandez C, Gatica D, Toro B, Quiroga C, Rodriguez AE, Sanchez G, Gillette TG, Hill JA, Donoso P, Lavandero S. Cardiomyocyte ryanodine receptor degradation by chaperone-mediated autophagy. Cardiovasc Res 98: 277–285, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pitts KR, Yoon Y, Krueger EW, McNiven MA. The dynamin-like protein DLP1 is essential for normal distribution and morphology of the endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria in mammalian cells. Mol Biol Cell 10: 4403–4417, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Quinsay MN, Thomas RL, Lee Y, Gustafsson AB. Bnip3-mediated mitochondrial autophagy is independent of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore. Autophagy 6: 855–862, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Reef S, Zalckvar E, Shifman O, Bialik S, Sabanay H, Oren M, Kimchi A. A short mitochondrial form of p19ARF induces autophagy and caspase-independent cell death. Mol Cell 22: 463–475, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rogov V, Dotsch V, Johansen T, Kirkin V. Interactions between autophagy receptors and ubiquitin-like proteins form the molecular basis for selective autophagy. Mol Cell 53: 167–178, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Salvador N, Aguado C, Horst M, Knecht E. Import of a cytosolic protein into lysosomes by chaperone-mediated autophagy depends on its folding state. J Biol Chem 275: 27447–27456, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Schneider JL, Cuervo AM. Autophagy and human disease: emerging themes. Curr Opin Genet Dev 26C: 16–23, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schneider JL, Suh Y, Cuervo AM. Deficient chaperone-mediated autophagy in liver leads to metabolic dysregulation. Cell Metab 20: 417–432, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sharp WW, Fang YH, Han M, Zhang HJ, Hong Z, Banathy A, Morrow E, Ryan JJ, Archer SL. Dynamin-related protein 1 (Drp1)-mediated diastolic dysfunction in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury: therapeutic benefits of Drp1 inhibition to reduce mitochondrial fission. FASEB J 28: 316–326, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shen HM, Mizushima N. At the end of the autophagic road: an emerging understanding of lysosomal functions in autophagy. Trends Biochem Sci 39: 61–71, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shiba-Fukushima K, Imai Y, Yoshida S, Ishihama Y, Kanao T, Sato S, Hattori N. PINK1-mediated phosphorylation of the Parkin ubiquitin-like domain primes mitochondrial translocation of Parkin and regulates mitophagy. Sci Rep 2: 1002, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Shoji-Kawata S, Sumpter R, Leveno M, Campbell GR, Zou Z, Kinch L, Wilkins AD, Sun Q, Pallauf K, MacDuff D, Huerta C, Virgin HW, Helms JB, Eerland R, Tooze SA, Xavier R, Lenschow DJ, Yamamoto A, King D, Lichtarge O, Grishin NV, Spector SA, Kaloyanova DV, Levine B. Identification of a candidate therapeutic autophagy-inducing peptide. Nature 494: 201–206, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Siddall HK, Yellon DM, Ong SB, Mukherjee UA, Burke N, Hall AR, Angelova PR, Ludtmann MH, Deas E, Davidson SM, Mocanu MM, Hausenloy DJ. Loss of PINK1 increases the heart's vulnerability to ischemia-reperfusion injury. PLoS One 8: e62400, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Singh R, Kaushik S, Wang Y, Xiang Y, Novak I, Komatsu M, Tanaka K, Cuervo AM, Czaja MJ. Autophagy regulates lipid metabolism. Nature 458: 1131–1135, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Soleimanpour SA, Gupta A, Bakay M, Ferrari AM, Groff DN, Fadista J, Spruce LA, Kushner JA, Groop L, Seeholzer SH, Kaufman BA, Hakonarson H, Stoffers DA. The diabetes susceptibility gene Clec16a regulates mitophagy. Cell 157: 1577–1590, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tannous P, Zhu H, Nemchenko A, Berry JM, Johnstone JL, Shelton JM, Miller FJ Jr, Rothermel BA, Hill JA. Intracellular protein aggregation is a proximal trigger of cardiomyocyte autophagy. Circulation 117: 3070–3078, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Twig G, Elorza A, Molina AJ, Mohamed H, Wikstrom JD, Walzer G, Stiles L, Haigh SE, Katz S, Las G, Alroy J, Wu M, Py BF, Yuan J, Deeney JT, Corkey BE, Shirihai OS. Fission and selective fusion govern mitochondrial segregation and elimination by autophagy. EMBO J 27: 433–446, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Vives-Bauza C, Zhou C, Huang Y, Cui M, de Vries RL, Kim J, May J, Tocilescu MA, Liu W, Ko HS, Magrane J, Moore DJ, Dawson VL, Grailhe R, Dawson TM, Li C, Tieu K, Przedborski S. PINK1-dependent recruitment of Parkin to mitochondria in mitophagy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 378–383, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Webster BR, Scott I, Han K, Li JH, Lu Z, Stevens MV, Malide D, Chen Y, Samsel L, Connelly PS, Daniels MP, McCoy JP Jr, Combs CA, Gucek M, and Sack MN. Restricted mitochondrial protein acetylation initiates mitochondrial autophagy. J Cell Sci 126: 4843–4849, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wing SS, Chiang HL, Goldberg AL, Dice JF. Proteins containing peptide sequences related to Lys-Phe-Glu-Arg-Gln are selectively depleted in liver and heart, but not skeletal muscle, of fasted rats. Biochem J 275: 165–169, 1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Xie M, Kong Y, Tan W, May H, Battiprolu PK, Pedrozo Z, Wang ZV, Morales C, Luo X, Cho G, Jiang N, Jessen ME, Warner JJ, Lavandero S, Gillette TG, Turer AT, Hill JA. Histone deacetylase inhibition blunts ischemia/reperfusion injury by inducing cardiomyocyte autophagy. Circulation 129: 1139–1151, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yamamoto S, Yang G, Zablocki D, Liu J, Hong C, Kim SJ, Soler S, Odashima M, Thaisz J, Yehia G, Molina CA, Yatani A, Vatner DE, Vatner SF, Sadoshima J. Activation of Mst1 causes dilated cardiomyopathy by stimulating apoptosis without compensatory ventricular myocyte hypertrophy. J Clin Invest 111: 1463–1474, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Zhang J, Ney PA. Role of BNIP3 and NIX in cell death, autophagy, and mitophagy. Cell Death Differ 16: 939–946, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zhu H, Tannous P, Johnstone JL, Kong Y, Shelton JM, Richardson JA, Le V, Levine B, Rothermel BA, Hill JA. Cardiac autophagy is a maladaptive response to hemodynamic stress. J Clin Invest 117: 1782–1793, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]