Abstract

Hearts from type 2 diabetic (T2DM) subjects are chronically subjected to hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia, both thought to contribute to oxidizing conditions and contractile dysfunction. How redox alterations and contractility interrelate, ultimately diminishing T2DM heart function, remains poorly understood. Herein we tested whether the fatty acid palmitate (Palm), in addition to its energetic contribution, rescues function by improving redox [glutathione (GSH), NAD(P)H, less oxidative stress] in T2DM rat heart trabeculae subjected to high glucose. Using cardiac trabeculae from Zucker Diabetic Fatty (ZDF) rats, we assessed the impact of low glucose (EG) and high glucose (HG), in absence or presence of Palm or insulin, on force development, energetics, and redox responses. We found that in EG ZDF and lean trabeculae displayed similar contractile work, yield of contractile work (Ycw), representing the ratio of force time integral over rate of O2 consumption. Conversely, HG had a negative impact on Ycw, whereas Palm, but not insulin, completely prevented contractile loss. This effect was associated with higher GSH, less oxidative stress, and augmented matrix GSH/thioredoxin (Trx) in ZDF mitochondria. Restoration of myocardial redox with GSH ethyl ester also rescued ZDF contractile function in HG, independently from Palm. These results support the idea that maintained redox balance, via increased GSH and Trx antioxidant activities to resist oxidative stress, is an essential protective response of the diabetic heart to keep contractile function.

Keywords: contractile work, rate of respiration, redox environment, antioxidant systems, oxidative phosphorylation, mitochondrial ros emission, Zucker diabetic fatty rat

a common complication of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is cardiomyopathy, characterized by diastolic and systolic dysfunction, which is likely impacted by alterations in metabolic substrate availability. Although the healthy heart is flexible regarding fuel selection, the high levels of glucose and fat in T2DM lead to questions about which factors contribute to dysfunction and which are beneficial as energy source or redox donors (35).

Fatty acids (FA) and glucose are the two major fuels driving heart contraction, and in T2DM and obesity existing evidence indicates increased FA oxidation (12, 15). The idea that FAs excess negatively regulates glucose oxidation in diabetes according to the Randle mechanism (33) remains a central postulate explaining some negative consequences of substrate shift in this metabolic disorder. However, it is now increasingly appreciated that hyperglycemia per se can trigger cellular damage, independently from FA utilization (11). The multiple mechanisms through which hyperglycemia may negatively affect cell function have been well described in endothelial tissue (26), but their role in the myocardium remains incompletely understood. Also extensive literature exists on the effects of high fat diets on the myocardium and skeletal muscle. Yet our knowledge about the combined effects of hyperglycemia and high FA availability on metabolism and redox/reactive oxygen species (ROS) balance is incomplete.

Although metabolic remodeling in diabetes has been extensively studied (15, 17, 33, 39), the involvement of redox metabolism in T2DM heart contractile dysfunction remains to be elucidated (53). To avoid misinterpretation, herein the term “redox” refers to the four main redox couples: NADH/NAD+, NADPH/NADP+, GSH/GSSG, and TrxSH2/TrxSS (21, 36). Little information is available on the mechanistic interactions between hyperglycemia and FAs on redox status in T2DM myocardium, although compelling evidence about the critical role played by perturbed cellular/mitochondrial redox, compromised mitochondrial energetics and elevated ROS at the origin of contractile impairment in diabetes, has been reported (1, 51).

We hypothesize that in T2DM hearts substrate selection in addition to its energetic role drives the redox environment of the myocardium, in turn modulating contractile function and determining resistance to oxidative stress. Using heart trabeculae simultaneously monitored for muscle mechanics, energetics, and redox status, we asked whether and how glucose levels in combination with Palm and insulin treatment influence the redox environment and the relationship between work output and mitochondrial respiration in lean and Zucker Diabetic Fatty (ZDF) rats. We show that ZDF myocardium is uniquely adapted to conditions encountered in T2DM. Cardiomyopathy in ZDF rats occurs independently from arteriosclerosis, making this animal model ideal for studying the development of myocardial complications (17).

METHODS

Experimental animals and trabeculae preparation.

All experimental procedures were approved by the Johns Hopkins University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), in compliance with National Institutes of Health guidelines. ZDF (fa/fa) and lean (+/fa or +/+) control male rats were obtained from Charles River. All animals were housed in a temperature-controlled room and fed ad libitum with Purina 5008 diet, which provides 16.7% of calories from fat.

Rats were heparinized (500 IU) 15 min before being euthanized with Na+ pentobarbital (180 mg/kg ip). Rats 14–17 wk of age were used for all experiments. Before euthanasia, lean versus ZDF animals exhibited the following average body mass (g ± SE) and blood glucose levels (mg/dL ± SE, nonfasted): 354 ± 13 vs. 430 ± 14 (P < 0.001) and 158 ± 6.3 vs. 495 ± 13.3 (P < 0.0001), respectively (n = 15–19). For Palm addition, FA plasma levels determined in 12–14 wk of age ZDF rats from published sources were taken as reference (Table 1). In all experiments, we used Palm bound to fatty acid-free albumin (4:1), prepared as described (51).

Table 1.

Free fatty acid concentration in serum or plasma of 14-wk-old lean and ZDF rats

| Lean | ZDF | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| 0.26 ± 0.02a | 0.56 ± 0.04 | 54 |

| 0.66 ± 0.01 | 1.26 ± 0.12 | 58 |

| 0.51 ± 0.059 | 1.49 ± 0.15 | 24 |

| 0.28 ± 0.02 | 0.83 ± 0.12 | 9 |

| 0.43 ± 0.097 | 1.04 ± 0.21 | means ± SD |

Values are means ± SE.

ZDF, Zucker Diabetic Fatty.

Fatty acid concentration in mmol/l of serum or plasma reported in each reference as means ± SD.

Heart trabeculae were isolated and mounted according to conditions described in Janssen and Hunter (34). The heart was immediately excised and perfused with Krebs-Henseleit (K-H) buffer containing 20 mM 2,3-butanedione monoxime. The K-H buffer (pH 7.4) contained (in mM) 120 NaCl, 5 KCl, 2 MgSO4, 1.2 NaH2PO4, 20 NaHCO3, 0.25 Ca2+, and 10 glucose. Unbranched trabeculae from the right ventricle were dissected and their dimensions measured with a calibrated eyepiece reticle. Trabeculae (average width, 0.34 ± 0.028 mm; thickness, 0.14 ± 0.01 mm; and area, 0.029 ± 0.002 mm2) were mounted between the basket shaped extension of a force transducer (SI-Heidelberg, Germany) and a hook-like arm of micromanipulator placed between platinum-iridium electrodes.

For cardiomyocyte or mitochondrial isolation, after rapid excision, the heart was either 1) cannulated via the aorta allowing for retrograde perfusion and ventricular myocytes isolation, as previously described (57) or 2) minced and processed for mitochondrial isolation as detailed elsewhere (3). The same batch of freshly isolated cardiomyocytes was used for assaying metabolic fluxes, two-photon imaging, contractility, and Ca2+ handling.

Muscle experimental set up.

After being mounted on force transducer, trabeculae were stabilized ∼30 min in K-H with 10 mM glucose (EG) in presence of 0.5 mM CaCl2 before being loaded with the fluorescent probes for 30 min (see below) in the absence of stimulation. Trabeculae were then perfused with K-H EG containing 1 mM CaCl2 while stimulated at 0.5 Hz, waiting until the force reached steady state to start recording O2 consumption and fluorescent signals as baseline measurements. Transition to the other substrate conditions, e.g., high glucose (HG), HG + palmitate (Palm), was done always in the presence of 1 mM CaCl2 and incubated for 15–20 min before recording signals for another 15–20 min.

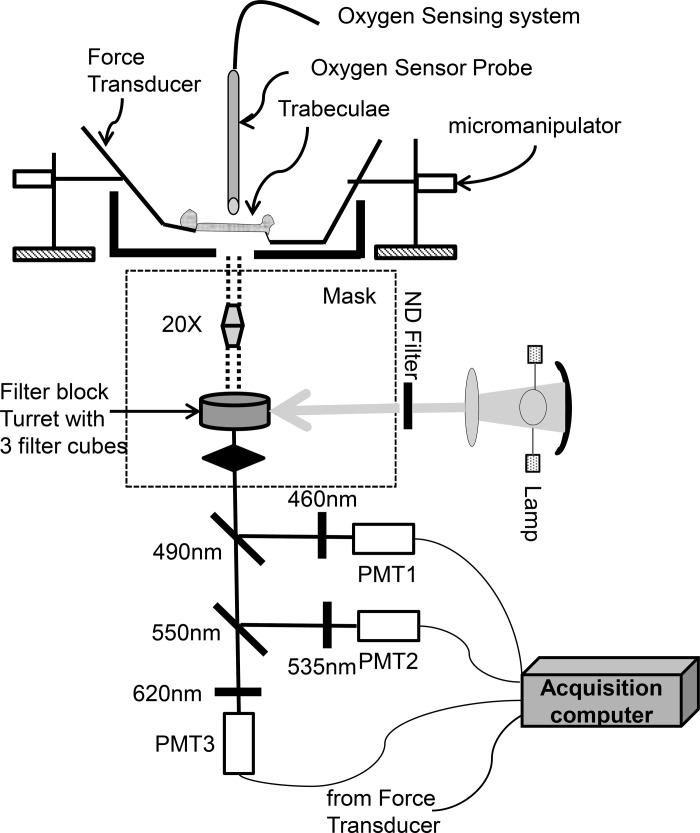

Trabeculae were field stimulated at 0.5 Hz or 1.5 Hz, and force was measured and expressed normalized to cross-sectional area in milliNewtons per squared millimeter. All experiments were performed at 25 ± 1°C in a flow chamber mounted on the stage of an upright microscope (Nikon, Eclipse TE2000U) (Scheme 1). Fluorescence was captured through photomultiplier detectors (Photon Technology International) attached to the microscope (Fig. 1). Trabeculae were judged healthy and apt for experimentation based on their capacity to contract and to respond to an increase in frequency as well as the status of mitochondrial energization monitored through the ΔΨm sensitive probe tetramethylrhodamine (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Diagram of the setup used to monitor the trabeculae tension, respiration, and fluorescent signals. For fluorescence measurements, the light from a mercury arc lamp, filtered through a neutral density (ND) filter passes through the filter cube turret in an inverted microscope (Nikon Eclipse, TE2000-U), where the excitation (exc.) can be chosen, is shown: 1) For NADH or GSB, exc. filter 350 nm and dichroic mirror acting as beam splitter (BS) 410 nm; 2) for CM-DCF, exc. filter 470 nm, BS 495 nm; 3) for MitoSOX, exc. filter 540 nm, BS 565 nm. The light emitted by the trabeculae reaches the photomultipliers (PMT; Photon Technology International) after selection by 2 dichroic mirror (BS 490 nm and 550 nm) and subsequently filtered at 460 nm (NADH and MCB signals), 535 nm (CM-DCF), and 620 nm (MitoSOX). Dichroic mirrors and filters (Chroma Technologies) were positioned as indicated in the diagram.

Trabeculae respiration measurements.

Muscle respiration was measured with a fluorescence-based fiber optic oxygen sensor (Ocean Optics, Dunedin, FL) using a stop-flow method (20). The rate of O2 consumption (VO2) was measured upon stopping the flow of perfusion buffer for 0.75–1 min. The VO2 was recorded in the linear range of detection and normalized with respect to the wet tissue mass facing the probe.

Contractile work of heart trabeculae.

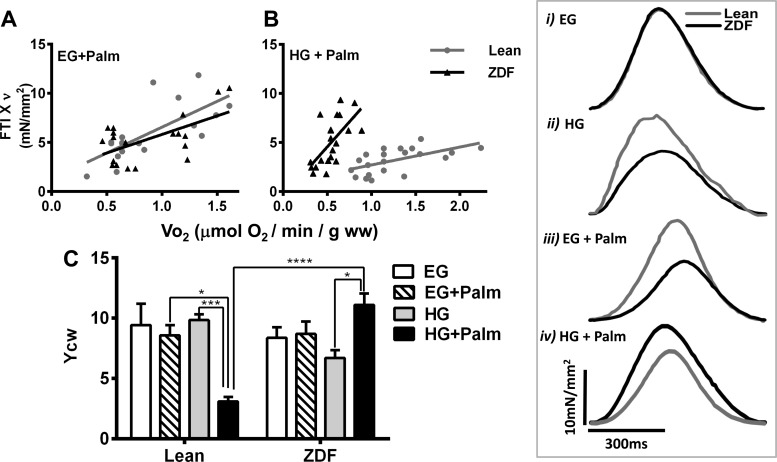

FTI×ν corresponds to the contractile work computed as the product between the integral of the curve of tension (force time integral, FTI) times the pacing frequency (ν). FTI×ν correlates linearly with VO2 (see Fig. 2), and the slope of this linear relationship represents the yield of contractile work (Ycw). YCW monitors systolic function since both force transient (developed force) and FTI are considered with respect to the diastolic level.

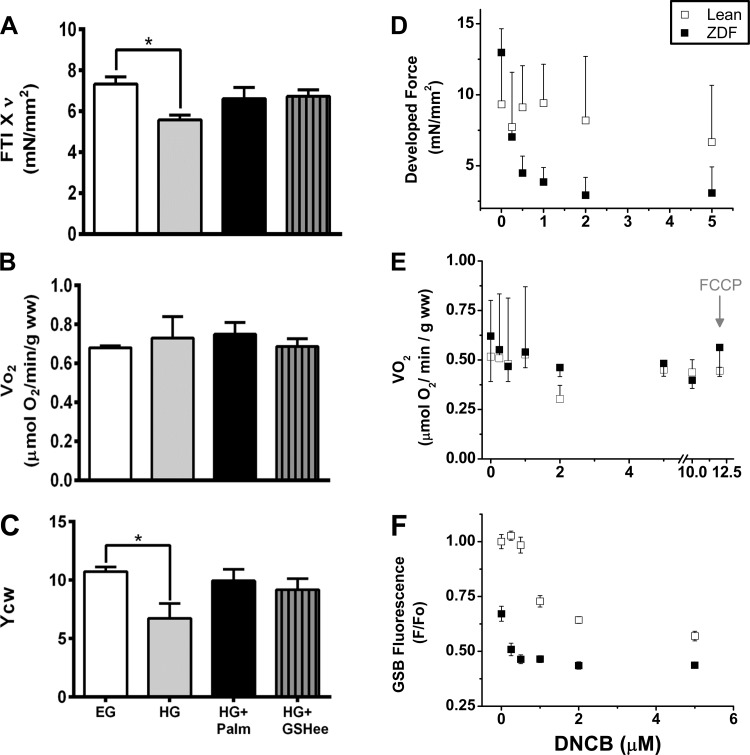

Fig. 2.

Contractile and energetic performance of heart trabeculae from lean and Zucker Diabetic Fatty (ZDF) rats. Cardiac trabeculae were subjected to increasing pacing frequency while perfused with oxygenated K-H with 10 mM glucose (EG) or 30 mM (HG) glucose without or with 0.4 mM [EG + palmitate (Palm)] or 0.8 mM Palm (HG + Palm) bound to fatty acid-free BSA (4:1) at a flow rate of ∼15 ml/min, in the presence of 1 mM Ca2+ at 25°C as described in methods. A and B: cardiac work per unit time (force time integral, FTI×ν) versus the rate of respiration (VO2), both registered simultaneously. C: contractile performance of trabeculae was measured as yield of contractile work, Ycw (see methods; n = 3–6 experiments per treatment). The muscle respiration values without stimulation (not included in the regression analysis) were (in μmol·min−1·g−1 WW): EG + Palm, 0.53 ± 0.02 (lean, n = 4) and 0.46 ± 0.05 (ZDF, n = 4); HG + Palm, 0.94 ± 0.08 (lean, n = 4) and 0.51 ± 0.11 (ZDF, n = 4). The traces in insets i-iv correspond to typical force transients exhibited by trabeculae under each combination of glucose and Palm while paced at 1.5 Hz. *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

Monitoring redox in heart trabeculae.

The redox status of heart trabeculae was monitored with either endogenous or fluorescent probes loaded into the tissue. NAD(P)H autofluorescence was monitored simultaneously with the oxidative stress fluorescent probes 5-(6)-chloromethyl-2, 7-dichloro-hydrofluorescein (CM-H2-DCFDA) and MitoSOX. GSH was determined with 50 μM monochlorobimane (MCB), a membrane-permeant indicator of GSH (2). Trabeculae were loaded with 7 μM CM-H2-DCFDA and 2 μM MitoSOX dissolved in 0.4% pluronic acid F-127, 0.1% DMSO, 5g/l cremophor, and 1 μM N,N,N′,N′ tetrakis (2-pyridylmethyl)ethylenediamine (48, 52).

Due to overlap of the fluorescence emission spectra of NADH and GSB, we performed separate experiments, where we monitored simultaneously the fluorescence from trabeculae loaded with either of the three following probe combinations: I and II: TMRM (ΔΨm) or MitoSOX (ROS) (red emission), CM-DCF (ROS, green), and autofluorescence (NADH, blue) or III: the same as I and II except for the blue emission in which trabeculae were loaded with MCB. In III, the NADH fluorescence contributes only 20–25% of the total signal at 450 nm, staying rather constant under the conditions tested herein. The NADH signal was calibrated by perfusion with 1 μM FCCP and 5 mM cyanide added successively after treatment of trabeculae with 2,3-butanedione monoxime (20 mM) at the end of the experiments.

Two photon laser scanning fluorescence microscopy.

Experiments with intact cardiomyocytes were carried out at 37°C in a thermostatically controlled flow chamber mounted on the stage of an upright microscope attached to a multiphoton laser scanning system (Olympus FV1000 MP). Cells were loaded with the fluorescent probes (Invitrogen, Eugene, OR) for 20 min at 37°C on the stage of the microscope and imaged as described (2) (see also legend of Fig. 4).

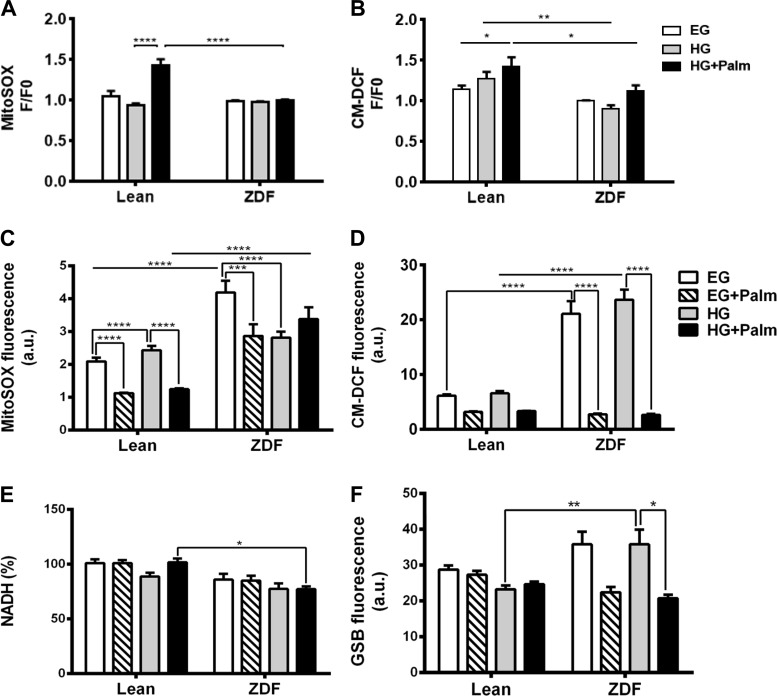

Fig. 4.

Impact of glucose/Palm combinations on redox status of heart trabeculae and cardiomyocytes. Cardiac trabeculae displayed are paired measurements of MitoSOX (A) and CM-DCF (B) fluorescence from lean (n = 4 hearts) and ZDF (n = 4 hearts) trabeculae subjected to the indicated substrate shifts. For cardiomyoctes, freshly isolated rat cardiomyocytes were imaged for MitoSOX (C), CM-DCF (D), NADH (E), and GSB (F) with 2-photon microscopy as described in methods. Cardiomyocytes were imaged in a chamber thermostated at 37°C while perfused with K-H, pH 7.4, containing 1 mM Ca2+ in EG for 30 min, followed by HG for another 30 min, without or with Palm: EG + 0.4 mM Palm or HG + 0.8 mM Palm bound to fatty acid-free BSA (4:1). Fluorescent signals correspond to paired determinations in 2 independent experiments with n = 30 for each experimental condition. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001. Au, arbitrary units.

Sarcomere shortening and calcium transients.

Isolated myocytes were studied at 25 ± 1°C as described (51).

Mitochondrial physiological studies.

Isolation and handling of mitochondria were as per prior studies (3). Respiration was assayed with the Seahorse flux analyzer XF96 at 37 ± 1°C as described (5). Mitochondrial protein and H2O2 were determined as described (5).

Mitochondrial GSH and GSSG determination.

After excision, lean and ZDF hearts were quickly perfused with K-H buffer to get rid of blood. A piece of heart tissue (∼100 mg) was processed for Western blot analysis (see below) while the remaining tissue was subjected to mitochondrial isolation as described above. After isolation, mitochondria were resuspended in buffer containing (in mM) 137 KCl, 2 KH2PO4, 0.5 EGTA, 2.5 MgCl2, and 20 HEPES (at pH 7.2), divided in two aliquots of 1 ml each, and assayed in state 4 respiration with 5 mM glutamate/5 mM malate for 5 min at room temperature with continuous stirring. The reaction was stopped with 1 ml of 5% metaphosphoric acid without or with 1-methyl-2-vinylpyridinium trifluoromethanesulfonate, M2VP (OxisResearch, a rapid GSH scavenger that does not interfere with the glutathione reductase assay) for reduced, GSH, or oxidized, GSSG, glutathione determination, respectively. Mitochondria were immediately subjected to three cycles of freeze (mixture of dry ice/ethanol for 5 min)-thawing (thermostated water bath at 37°C for 5 min), the suspension centrifuged for 15 min at 13,000 g in a cold room, and the supernatant recovered and stored at −80°C for GSH/GSSG analysis. The total GSH or GSSG was determined with the commercially available kit from Bioxytech (GSH/GSSG-412), with slight modifications for 96-well microplate reader using a Flex Station 3 (Molecular Devices). The absolute concentrations of GSH or GSSG present in the samples were estimated using a mitochondrial volume of 2 μl/mg mitochondrial protein (4, 49) and the amount of protein in the sample determined according to the bicinchoninic acid method (BCA protein assay kit; Thermo Scientific).

Western blot analysis.

Heart tissue (100 mg) was homogenized with Polytron for ∼45–60 s in 0.5 ml of buffer containing (in M) 6 urea, 0.001 EDTA, 0.001 dithiothreitol, 0.05 Tris·HCl (pH 7.5), and protease inhibitor. The homogenate was centrifuged for 15 min at 13,000 g in a cold room, and the supernatant recovered and stored at −80°C for further analysis. Samples were run on 4–12% pre-cast Bis-Tris gels (Invitrogen), transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and blotted using antibodies for thioredoxin, Trx (peroxiredoxins 1 and 3, Prx1 and Prx3; thioredoxin reductases 1 and 2, TrxR1 and TrxR2; thioredoxin, Trx) and GSH (glutathione reductase 1, GR1; glutathione peroxidases 1 and 4, GPx1 and GPx4) scavenging pathways: Abcam ab184868 (antibody cocktail for Prx1, TrxR1, Trx); ab55075 for GR1; ab59546 for GPx1; ab73349 for Prx3; ab125066 for GPx4; and 3F2-E12-F10 for TrxR2 (Cell Signaling). Blots were scanned using an Odyssey Infrared Imager (Li-Cor Biosciences, Lincoln, NE) and analyzed using Odyssey Application Software (v3.0.30; Li-Cor Biosciences).

Statistical analysis.

Data were analyzed with the software GraphPad Prism (Ver. 6; San Diego, CA) or MicroCal Origin. The statistical significance of the differences between groups and treatments was evaluated with two-way ANOVA using Tukey's multiple comparison test or with a t-test (small samples, paired t-test with two-tail P values), and the results are presented as means ± SE (95% confidence interval).

RESULTS

Effects on contractile and energetic performance in diabetic heart trabeculae and cardiomyocytes exposed to different glucose and Palm combinations.

We explored the effects of glucose concentration or glucose + Palm on contractile and energetic responses of trabeculae from T2DM hearts in comparison with lean controls. Trabeculae were mounted in a force transducer and superfused with low (EG, 10 mM) and high (HG, 30 mM) glucose in the absence or presence of Palm, when subjected to low (0.5 Hz) or moderate (1.5 Hz) pacing frequencies.

Contractile work, monitored through FTI × ν, as a function of the rate of O2 consumption (VO2), is shown in Fig. 2, A and B. Figure 2C depicts the Ycw as a function of different glucose/Palm combinations. Substrate combinations include 1) EG + Palm: both lean and ZDF were exposed to 10 mM glucose + 0.4 mM Palm or 2) HG + Palm: both groups were exposed to 30 mM glucose + 0.8 mM Palm. The rationale of the combinations was to compare trabeculae challenged by the same substrate combination at concentrations similar to blood levels found in lean (EG + 0.4 mM Palm) or ZDF (HG + 0.8 mM Palm) rats (Table 1).

In EG without or with Palm, the Ycw of ZDF and lean trabeculae were similar (Fig. 2C). In contrast, in HG alone the Ycw of ZDF trabeculae were lower than in lean. In HG, Palm addition significantly improved Ycw in ZDF trabeculae, whereas Ycw was significantly depressed by Palm in lean trabeculae (Fig. 2C). The improved Ycw in ZDF with HG + Palm was evident as enhanced peak tension for the individual twitches (inset i-iv). Unlike in EG (inset i), lean and ZDF trabeculae behaved conspicuously different in HG: lean trabeculae exhibited higher amplitude and shorter time-to-peak tension than ZDF (inset ii). Addition of Palm in EG further decreased the rate of force development in ZDF muscle (inset iii). Strikingly, in HG, Palm addition significantly enhanced peak tension in ZDF, but not lean, muscles rendering a higher FTI in ZDF than in lean (inset iv).

The improvement in Ycw with HG + Palm in ZDF was given by a steeper dependence of FTI×ν on VO2 as compared with lean that displayed broader VO2 span (Fig. 2B). No significant differences in VO2 could be detected between ZDF and lean in EG + Palm, suggesting that ZDF trabeculae have adapted in HG to transduce more efficiently the energy from Palm into respiration and mechanical work.

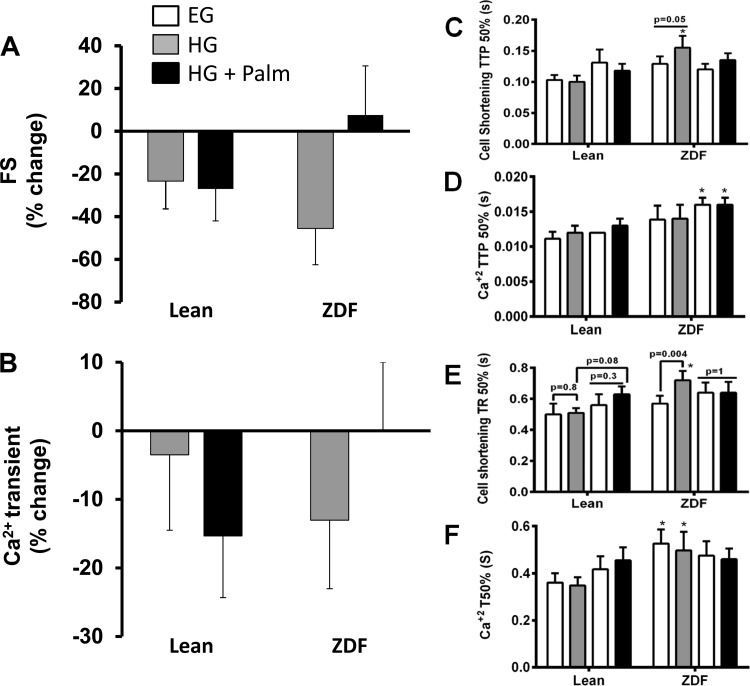

To further investigate the status of Ca2+ handling as a function of contractile behavior, we isolated ventricular cardiomyocytes and analyzed them under different substrate combinations. HG negatively affected fractional shortening (FS) in both lean and ZDF myocytes, although only significantly in ZDF. Interestingly, Palm protected FS in ZDF but not in lean cardiac myocytes (Fig. 3A). The Ca2+ transient exhibited a similar trend as the FS. The decrease in the amplitude of the Ca2+ transient was higher although not significantly in ZDF than lean, and Palm rescued the ZDF Ca2+ transient to baseline level (Fig. 3B). The FS and Ca2+ transient changes were accompanied by corresponding alterations in kinetics. Both the time to peak and the time to baseline are longer in ZDF than lean trabeculae, especially in HG (Fig. 3, C–F). This is indeed an indication of diastolic dysfunction, characteristic of the early stages of diabetic cardiomyopathy (47).

Fig. 3.

Relative fractional shortening (FS) and Ca2+ transients of cardiomyocytes from lean and ZDF rats. Freshly isolated rat cardiomyocytes from lean and ZDF hearts in EG were challenged with HG or HG + Palm (see Fig. 2 legend) while stimulated at 0.5 Hz at 25 ± 1°C. The bars show the percent change in FS (A) and Ca2+ transient amplitude (B) from the values in EG. In EG, FS was 1.8% with Ca2+ transients reaching a 64% increase over diastolic levels in lean cardiomyocytes with a 1.2% FS and 40% increase over resting Ca2+ in ZDF cardiomyocytes. Upstroke kinetics of sarcomere shortening and Ca2+ transient are displayed in C and D, respectively, where TTP 50% stands for time from baseline to 50% peak. Also depicted are time to 50% relengthening (TR50) from myocyte sarcomere (E) and T50 time to 50% Ca2+ transient decay (F). n = 8–15 cells from 2 hearts for each group and treatment. The legend included in A provides a key for bars in all panels. *P < 0.05.

The results show that the contractile and Ca2+ handling functions of heart trabeculae and cardiomyocytes from diabetic animals in HG can be rescued by Palm, apparently via a more efficient conversion of mitochondrial energy into contractile work.

Role of redox status in preserving contractility of diabetic heart trabeculae.

Next, we investigated whether the redox status of trabeculae was involved in the contractile performance improvement exhibited by the diabetic muscle in HG + Palm.

First, we performed paired measurements of oxidative stress with two different probes in lean and ZDF trabeculae, MitoSOX and CM-H2-DCFDA (CM-DCF). Although, in HG, Palm increased oxidative stress in lean, it was unable to do so in ZDF (Fig. 4, A and B), demonstrating that the diabetic muscle is able to better control redox. As a caveat, it is not possible to observe a decrease in fluorescence of the oxidative stress probes because their oxidation is irreversible.

Second, we systematically analyzed the redox response in cardiomyocytes subjected to glucose/Palm under conditions mimicking the trabeculae experiments to gain mechanistic insight. NADH was ∼20% more oxidized in ZDF quiescent cardiac myocytes regardless of substrate (Fig. 4E). However, ZDF exhibited higher GSH levels both in EG and HG in absence of Palm compared with that of lean (Fig. 4F). The decrease in GSH triggered by Palm in HG, together with the resulting lower oxidative stress, suggested that steady ROS levels were maintained at the expense of the GSH pool (Fig. 4, C and D).

Third, we determined whether an improvement of the intracellular antioxidant pool, independently from the presence of Palm, is able to preserve contractility. In HG, ZDF trabeculae pretreated with GSH ethyl ester (GSHee), a cell permeable form of GSH (Fig. 5, A–C) (51), both work (FTI × ν) and YCW were improved to similar values as those shown in EG or HG + Palm (Fig. 5, A and C) at unchanged VO2 (Fig. 5B). These results are consistent with those obtained upon addition of increasing concentrations of the GSH-depleting agent 1-chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene (DNCB) (49) to lean and ZDF trabeculae (Fig. 5, D–F). In previous work, we demonstrated that incubation of mitochondria with DNCB can increase ROS emission by depleting GSH levels in the absence of any effect on TrxR2 or Prx3 (49). ZDF trabeculae were more vulnerable than lean to DNCB action, which led to decreased contractility, measured as developed force (Fig. 5D). However, mitochondrial respiration was not affected (Fig. 5E), suggesting a larger effect of DNCB on cytoplasmic than on mitochondrial GSH (Fig. 5F).

Fig. 5.

Effect of GSH ethyl ester (GSHee) and 1-chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene (DNCB) on contractile and energetic performance of heart trabeculae from lean and ZDF rats. A–C: depicted are the cardiac work (A), VO2 (B), and Ycw (C) from ZDF trabeculae subjected to 1.5 Hz pacing while sequentially perfused with oxygenated K-H buffer containing 10 mM glucose (EG, n = 10–14 trabeculae). After 60 min perfusion the buffer was changed to either 30 mM glucose (HG, n = 10–14) or HG + 0.8 mM Palm (n = 10–14). In the case of HG + GSHee (n = 7 hearts), trabeculae were perfused with 2 mM GSHee in the last 10 min of EG perfusion then transitioned to HG buffer. Results are means ± SE values. D–F: increasing concentrations of the GSH depleting agent DNCB were added to either lean or ZDF trabeculae in EG stimulated at 1.0 Hz without Palm while developed force (D), respiration (E), and GSH as GSB with the fluorescent probe MCB (GSH-monochlorobimane) (F) were simultaneously monitored. After 20 min equilibration at each concentration the developed force (n = 20–30), respiratory rate (n = 3), and GSB (n = 600 twitches) were determined. Results are means ± SE from 2 to 3 heart trabeculae. *P < 0.05.

Together, these results show that enhancement of redox balance per se in HG (without Palm) improves contractility in diabetic heart trabeculae, suggesting a causal rather than correlative relationship between redox status (via intracellular GSH) and mechanical performance.

Insulin effect on contractile/energetic/redox behavior of working diabetic heart trabeculae.

The T2DM ZDF rat is characterized by insulin resistance. Therefore, we asked whether insulin would influence the ability of Palm to improve Ycw in ZDF, as compared with lean trabeculae when challenged with HG. The paired contractile/energetic and redox behavior of heart trabeculae from both groups were monitored under different substrate and insulin combinations at 0.5 and 1.5 Hz.

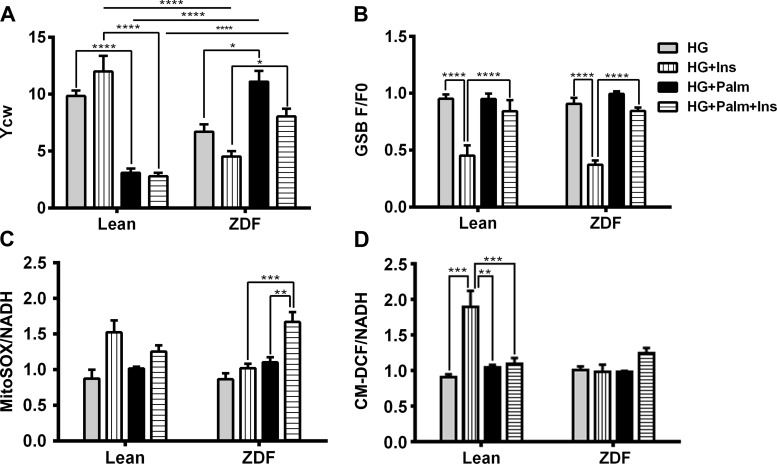

As expected from the insulin resistant ZDF, in HG alone, Ycw (Fig. 6A, and results not shown) was potentiated by insulin in lean but decreased in ZDF. Conversely, in ZDF trabeculae challenged with insulin and HG, Palm strongly enhanced Ycw (Fig. 6A, and results not shown) as compared with that in lean. The latter result was similar to that obtained in the absence of insulin (Fig. 2B), confirming that the beneficial action of Palm occurs independently from insulin in diabetic heart trabeculae.

Fig. 6.

Effects of insulin (Ins) on contractility/energetics and redox in heart trabeculae from lean and ZDF under different glucose/Palm combinations. Cardiac trabeculae were subjected to 0.5 and 1.5 Hz pacing while perfused with oxygenated K-H buffer in the absence or presence of insulin (10 nM) in HG without or with Palm as described in the legend of Fig. 2. Depicted are Ycw (A), GSB (B), MitoSOX (C), and CM-DCF (D) normalized with NADH that was monitored simultaneously (n = 3–6 experiments per treatment). Fluorescent signals (F) were normalized with respect to their corresponding value at the beginning of the experiment (F0) as indicated. Muscles were field stimulated at 0.5 Hz and allowed to stabilize for at least 30 min before loading fluorescent probes. Ca2+ concentration was 0.5 mM during the stabilization period. After probe loading, extracellular Ca2+ was raised to 1 mM. F0 was recorded in each trabecula equilibrated with the indicated substrate combination at 0.5 Hz in the absence of insulin (see methods). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

In lean trabeculae, and with respect to the condition in its absence, insulin appeared to augment oxidative stress in HG, as evidenced by decreased GSH with increased MitoSOX and CM-DCF signals (Fig. 6, B–D). Interestingly in ZDF muscles, HG + Ins treatment significantly decreased GSH levels, but there was no evidence of increased ROS accumulation (MitoSOX and CM-DCF signals were unchanged) (Fig. 6, B–D). HG + Palm + Ins was the only condition for which a ROS increase could be detected in ZDF muscles as an increase in MitoSOX signal (Fig. 6C).

Redox and contractile behavior of lean and ZDF trabeculae were also studied in EG and EG + Palm in the presence of insulin. Similar results to those observed in HG were obtained, i.e., ZDF trabeculae perform better in controlling their redox balance than lean trabeculae (results not shown).

Together, the evidence presented suggest that ZDF trabeculae are better adapted to scavenging ROS in HG, particularly when Palm is present, and that the beneficial action on cardiac contraction by this FA happens independently from insulin.

Respiration, ROS emission, and antioxidant status in heart mitochondria from control and diabetic rats.

The trabeculae energetic response and the kinetics of cardiomyocytes contraction/relaxation from lean and ZDF rats differ substantially depending on substrate (Figs. 2 and 3, C–F). To test the hypothesis that the differences in contractile performance can be explained by the energetic/redox status of mitochondria, we next examined the properties of isolated mitochondria from lean and diabetic animals.

We measured VO2 for mitochondria using substrates of complex I, II, and IV and determined the coupling of OxPhos through the Respiratory Control Ratio (RCR, state 3/state 4). ZDF mitochondria displayed lower VO2 than lean controls respiring on substrates of complex I (glutamate plus malate, G/M 5 mM each) (Fig. 7B), complex II (Succinate, Succ 5 mM) (Fig. 7C), or complex IV (0.5 mM N,N,N9,N9-tetramethyl-p-phenylenediamine, TMPD, and 3 mM sodium ascorbate) (Fig. 7D). RCR from lean mitochondria was significantly higher than ZDF with complex I substrates and not significantly different with the other substrates (Fig. 7A). The most notable difference between groups was the response to the mitochondrial uncoupler dinitrophenol (DNP). Uncoupled respiration increased more in lean than ZDF w.r.t. state 3 respiration, indicating a larger respiratory reserve in lean. There was almost no respiratory reserve with complex II substrate for ZDF mitochondria (Fig. 7, B–D). These results suggest that electron flow through the respiratory chain limits respiration in ZDF mitochondria (46).

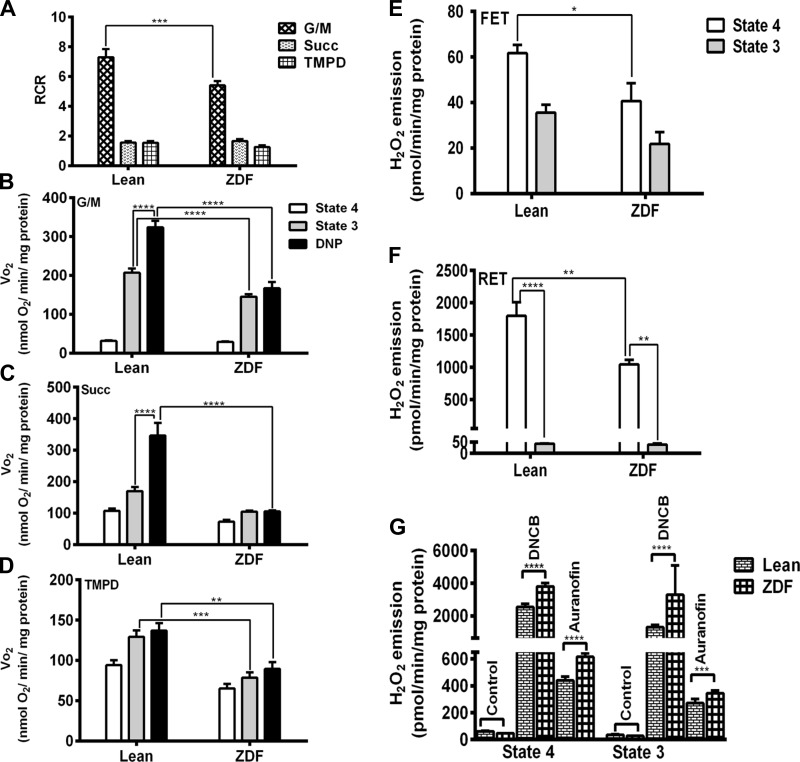

Fig. 7.

Respiratory rates and H2O2 emission from lean and ZDF heart mitochondria. VO2 was measured in freshly isolated heart mitochondria from lean and ZDF rats with a Seahorse XF96 as described in methods. Mitochondria were assayed under states 4 and 3 (with 1 mM ADP) respiration and fully uncoupled with dinitrophenol (DNP; 70 μM) in the presence of substrates from complex I (B), II (C), and IV (D). Respiratory control ratio (RCR) was estimated as state 3/state 4 (A). A–D correspond to n = 6, 2 experiments. H2O2 was monitored with the Amplex Red (ARed) reagent. The results of H2O2 emission in states 4 and 3 respiration are shown under forward electron transport (FET; E) and reverse electron transport (RET; F). H2O2 (100 pmol) was added for calibration. H2O2 emission in state 4 or 3 respiration (G) are depicted before and after GSH pool depletion with 10 μM DNCB or inhibition of Trx2 system with 100 nM Auranofin (AF). E–G correspond to n = 4, 2 experiments. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001.

Next, we asked whether the redox behavior of ZDF mitochondria was altered. To assess this we quantified H2O2 emission in the absence or the presence of specific inhibitors of GSH and thioredoxin (Trx) ROS scavenging systems (5, 49). ROS emission was significantly higher in lean than ZDF mitochondria both under forward (5 mM G/M) and reverse (5 mM Succ) electron transport in state 4 (Fig. 7, E and F). In state 3, H2O2 emission was decreased significantly under reverse and tended to be lower under forward electron transport in both lean and ZDF (Fig. 7F).

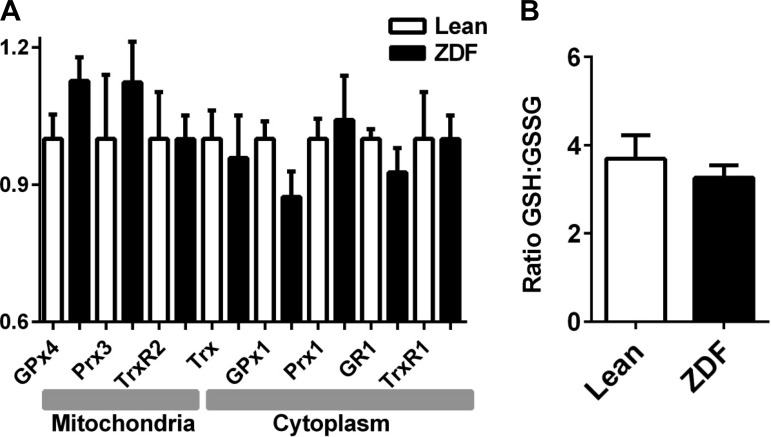

H2O2 emission upon maximal inhibition of GSH or Trx system measures the extent of control on ROS emission exerted by each branch of the mitochondrial antioxidant defenses (5). Thioredoxin reductase (TrxR2) was inhibited with auranofin (AF), and GSH was depleted with DNCB, that forms an adduct with GSH (49). Figure 7G displays the rates of H2O2 emission at saturating level of inhibition of the scavenging systems. Under these conditions, mitochondrial H2O2 release was greater in ZDF mitochondria than in lean when either of the antioxidant pathways were inhibited (Fig. 7G). This result suggests higher capacities to both generate as well as to scavenge ROS in ZDF. In principle, this result is in agreement with the slight but nonsignificant increase in the protein level of mitochondrial peroxidases from the GSH (GPx4) and Trx (Prx3) systems in ZDF (∼13% in both cases) with respect to lean. A trend to lower, but also nonsignificant, level of cytoplasmic GPx1 (∼13%) was also present in ZDF (Fig. 8A).

Fig. 8.

Mitochondrial GSH/GSSG and Western blot analysis of protein levels from GSH/Trx antioxidant systems in cytoplasmic and mitochondrial compartments. A: tissue homogenates of the same hearts from which mitochondria are isolated, were processed for Western blot analysis of different components of the GSH/Trx scavenging systems. Displayed are, for each indicated antioxidant component, means ± SE of the protein level in ZDF normalized to the mean of lean controls in each membrane. Protein loading in each well was normalized by ponceau staining (n = 7 hearts). B: freshly isolated mitochondria were processed for GSH and GSSG determination (see methods). The ratio of GSH:GSSG corresponding to state 4 respiration was determined from the absolute concentrations of both molecular species (see main text; n = 4 hearts).

The mitochondrial GSH:GSSG ratio at state 4 respiration with 5 mM G/M was not significantly different between groups, with concentration values for GSH (mM ± SE, n = 4): Lean = 0.9 ± 0.08 and ZDF = 0.7 ± 0.06, and GSSG (mM ± SEM; n = 4): Lean = 0.255 ± 0.035 and ZDF = 0.215 ± 0.015 (Fig. 8A). The mitochondrial GSH concentration determined (∼1 mM) is within the range of values found in mice (1–1.5 mM) (49) and guinea pig (1 to 2 mM) (21).

In summary, ZDF mitochondria display lower respiration, OxPhos coupling, and respiratory reserve than lean controls. The lower ROS emission by ZDF mitochondria appears to be due to a higher kinetic turnover capacity of the GSH/Trx antioxidant systems that keep a similar GSH:GSSG ratio compared with lean and eliminate 99% of the ROS generated (98% in lean).

DISCUSSION

We investigated the role of substrate-driven redox status on the contractile/energetic performance of heart trabeculae from the T2DM ZDF rat. The main findings are 1) HG exerts a detrimental action on contractility of T2DM heart trabeculae that Palm is able to rescue; 2) Palm prevents oxidative stress exacerbated by HG, an effect independent from insulin action; 3) insulin appears to worsen the negative effect of HG through higher oxidative stress and lower GSH; 4) ZDF heart mitochondria emit less ROS and display higher ROS scavenging capacity of the GSH/Trx antioxidant systems; and 5) cardiac redox balance in HG appears to play a causal rather than correlative role in the preservation of contractile performance in ZDF trabeculae.

Substrate selection and cardiac contractile performance.

Substrate selection, i.e., glucose-FAs, and insulin have a direct impact on diabetic muscle energetics/redox status, thereby affecting contractile performance. Mechanistically, ROS can induce post-translational modifications of key-components of excitation-contraction (EC) coupling, shaping their functional performance (13, 14). Moreover, mitochondrial failure to provide enough ATP underscores abnormal function of Ca2+ channels and pumps in the diastolic and systolic dysfunction associated with diabetic cardiomyopathy (10, 47).

Unlike in ZDF trabeculae where HG + Palm exerted a positive effect on contractile work, the opposite was observed in lean trabeculae (Fig. 2). Likely, this difference is due to mechanisms that operate in the diabetic ZDF but not lean trabeculae. Protective mechanisms involving higher antioxidant turnover of the GSH/Trx systems in the mitochondrial matrix (Figs. 7 and 8) may occur in response to the more oxidized environment exhibited by ZDF cardiomyocytes in HG (Fig. 4E). Overall, the ZDF muscle exhibits a better control of its redox status (Fig. 4, A and B), and restoration of cellular/mitochondrial cardiac redox balance in HG may play a causal rather than correlative role for preserving contractility (Fig. 5) (51). Together, these data suggest that GSH regeneration and ROS scavenging underlie enhanced contractility in T2DM. Reported data is also in agreement with the critical role played by cellular/mitochondrial redox and compromised mitochondrial energetics on heart dysfunction (1, 51).

Alterations of myocardial substrate metabolism have been implicated in the pathogenesis of contractile dysfunction and heart failure (38, 42). In diabetic cardiomyopathy metabolic perturbations are characterized by a shift to FA consumption (39), unlike nonischemic cardiomyopathy and animal models of heart failure that exhibit decreased FA and increased glucose utilization (22). The effect of substrate selection on muscle contractility depends on workload. Under loaded conditions the muscle is stretched to reach the optimal sarcomere length, thus different from unloaded Langendorff-perfused hearts (54). Also the detrimental effects of hyperglycemia were evident only in the presence of the higher energetic demand imposed by β-adrenergic stimulation in diabetic mice (51).

Perturbation of EC coupling in cardiac myocytes is a central impairment in diabetic cardiomyopathy (10, 28, 47) and in heart failure (6, 44). Contractility and EC coupling studies in cardiac trabeculae from streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat subjected to low glucose were reported before (60). These authors found that the kinetics of contraction and Ca2+ transient (e.g., upstroke, relaxation) were related but not their amplitudes leading them to conclude that EC coupling did not underlie the mechanical dysfunction of diabetic hearts. In ZDF cardiomyocytes the altered kinetics of Ca2+ transients was attributed to deficient SERCA2 and L-type Ca2+ channel activities (30, 31, 37). Our data indicate that EC coupling can be rescued in diabetic but not lean muscle subjected to HG + Palm as indicated by the close correspondence in the recovery of energetic coupling to mechanical function (Fig. 2B) and Ca2+ dynamic behavior (Fig. 3).

An original observation of this work is to show that Palm in HG may rescue contractility in diabetic heart trabeculae but not in lean controls, where Palm was detrimental. Therefore, the results obtained with lean trabeculae are in agreement with several studies before where negative effects of Palm on different aspects of EC coupling were found. Regarding contractility, and to the best of our knowledge, most of the reported data were obtained with low glucose (5 to 11 mM) (12, 17, 29, 40, 55, 59). Other work employing HG studied the heart susceptibility to ischemia-reperfusion injury in normal, nondiabetic rats (54). Boardman et al. (8) studied transitions from 5 to 26 mM glucose in T2DM (db/db) mouse hearts and observed decreased VO2 concomitant with increased glucose versus FA oxidation, but the effects on contractility were not reported. Regarding cardiomyocyte excitability, it has been shown that Palm can reduce the Ca2+ transient amplitude and shorten the action potential via activation of sarcolemmal outward K+ current leading to membrane potential repolarization (27). On the other hand it may activate voltage-dependent Ca2+ currents eventually triggering arrhythmogenic afterdepolarizations as well as induce cytotoxic Ca2+ overload (32). Although different cellular types (nondiabetic cardiomyocytes) and conditions (e.g., workload vs. resting, glucose levels) preclude strict comparison, our results with lean controls are in agreement with published data (e.g., decrease in Ca2+ transient amplitude with Palm in lean but not ZDF) (Fig. 3).

Mitochondrial behavior can be different between the different T2DM animal models that we examined (db/db mice and ZDF rat). Wild-type and db/db state 3 mitochondrial respiration from substrates of Complex I and II was similar in mice (51) but significantly lower in ZDF compared with lean control (Fig. 7, B–D). Impairment in the electron transport chain occurs in diabetic rat according to maximal respiratory rates in the presence of uncoupler (Fig. 7) (46). The rate of mitochondrial H2O2 emission from diabetic mice and rat behaves oppositely, i.e., larger than control in mice (51) but lower in rat (Fig. 7E). This difference might be due to increased scavenging capacity of mitochondrial GSH/Trx antioxidant systems in diabetic rats (Fig. 7G) and decrease in thioredoxin reductase activity in db/db mice (51).

Mechanical efficiency for intact heart has been defined as the ratio of external cardiac power to cardiac energy expenditure (7). The latter was estimated from myocardial oxygen consumption, MVO2, given that the heart meets >95% of its energetic requirements under normal conditions via oxidation of carbohydrates and FAs (39). On these premises, previous findings stated that the cardiac efficiency is higher for a given MVO2, when the myocardium has relatively low rates of FA respect to glucose and lactate oxidation (29, 39). The Ycw reported herein is the equivalent in trabeculae to the cardiac mechanical efficiency reported previously. The cardiac work output measured by FTI×ν is a more representative metric in our case because it captures the integral of the force (Fig. 2).

Insulin, glucose, and FA catabolism.

The effects of insulin under HG were difficult to attribute only to effects on glucose uptake and utilization. The largest changes were the increased oxidative stress in lean trabeculae (both under HG and EG), and the decrease in contractile performance in ZDF. Insulin-stimulated ROS levels have been reported before. In primary rat adipocytes basal and insulin-stimulated cellular H2O2 levels were increased in high glucose medium, and the extent of the response was dependent upon GSH levels (56).

At present we cannot rule out effects due to insulin-activated signaling on contractility. Diabetes increases the risk of heart failure (43) that in turn corresponds to an insulin-resistant state (19) associated with elevated sympathetic adrenergic activity (18) and impaired insulin-mediated glucose uptake in the myocardium (19). Contractile function in the heart is regulated via stimulation of β-adrenergic receptors (βARs). An adverse cross-talk between insulin and adrenergic stimulation signaling pathway was recently shown (25). Human T2DM is associated with hyperinsulinemia and activation of myocardial insulin signaling via insulin receptor (IR) (19). Insulin was able to directly impair the adrenergic signaling pathway for contractile function via an IR-β2AR signaling complex in animal hearts, providing a plausible mechanism for damage of myocardial inotropic reserve in T2DM subjects (25).

FAs excess and accumulation have been linked to increased oxidative stress and appearance of insulin-resistance in skeletal and cardiac muscles (23, 41, 45). In the heart, the metabolic shift promoting FA over glucose oxidation was proposed to be positive in the short-term alleviating intracellular glucose accumulation and toxicity (16, 45). The worsening effect on oxidative stress produced by insulin in lean and ZDF (Fig. 6) suggests a link between increased glucose consumption/oxidation and ROS overflow. Imaging studies of redox status performed in parallel with measurements of glycolytic and OxPhos fluxes in isolated cardiac myocytes from lean and ZDF hearts revealed that a negative effect of HG rather than an inhibitory action of Palm is a much more important factor diminishing the glycolytic flux (results not shown); both lean and ZDF displayed 66% and 50% lower glycolysis, respectively, independently from Palm. Results also indicated that, differently from lean, ZDF cardiomyocytes are able to better preserve metabolic fluxes in HG irrespective of Palm, as can be judged by relatively constant flux values across conditions. However, these results correspond to quiescent cells and as such are different from those obtained with working heart preparations in the presence of Palm although in normal 11 mM glucose (12, 29).

Present results suggest that workload and redox participate in the modulation of glucose catabolism in the T2DM cardiac muscle. Additional work is needed to clarify the molecular mechanisms underlying glucotoxicity and the positive effect of Palm on both redox stress and contractility in high glucose.

Limitations of the present study.

Heart trabeculae were studied at lower pacing frequencies than in vivo and at room temperature. The utilization of these conditions is justified to ensure that the tissue does not become hypoxic or substrate-starved in the center (34) and to decrease the rate of fluorescent probes degradation. Temperature also influences the rate of fluorescent probe degradation in the experiments with isolated cardiomyocytes loaded with FURA 2-AM for monitoring Ca2+ transients, also justifying the temperature choice. In whole hearts, temperature has been reported to affect Ca2+ transients and contractility (50). To overcome diffusion restrictions, relatively higher insulin level than present physiologically were used with trabeculae. As a caveat, the use of CM-DCF and MitoSOX probes was intended as indicators of oxidative stress rather than specific ROS species. Although a new generation of more specific ROS probes is becoming available they are not suitable yet for intact working cardiac trabeculae. Moreover, our assessment of the redox status involves the simultaneous measurement of other key redox reporters like NAD(P)H and GSH.

Regarding substrate concentration, not all the possible combinations between glucose and Palm levels in the perfusion solution were tested. The criterion followed in the substrate combinations tested was to approximately mimic the blood circulating levels of glucose and Palm found in lean or diabetic rats (Table 1).

The ZDF animal model enables a more targeted dissection of myocardial pathways affected by diabetes, in the absence of atherosclerosis and coronary artery disease. Consequently, the results found are not directly translational to humans that suffer from these comorbidities.

Concluding Remarks

In conclusion, here we show that substrate selection modulates the redox status and contractile performance of intact cardiac muscles under T2DM. In presence of hyperglycemia, the T2DM heart transduces more energy from Palm into force generation, and this enhanced ability is due to higher availability of GSH and consequently lower oxidative stress in the myocardium. The higher antioxidant turnover capacity of both GSH and Trx antioxidant systems in the mitochondrial matrix chiefly contributes to this favorable chain of events. Our study suggests where antioxidant therapies should be directed to prevent or blunt the deterioration of cardiac mechanical function in T2DM hearts that are constantly exposed to hyperglycemia and hyperlipidemia. It also highlights that failure of these protective redox-based mechanisms are major determinants of cardiomyopathy in T2DM subjects.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R21HL-106054, R01HL-091923 and S10R-R26474.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: N.M.B., M.A.A., and S.C. conception and design of research; N.M.B., M.A.A., C.G.T., X.S., S.D., G.R.-C., W.D.G., and S.C. performed experiments; N.M.B., M.A.A., C.G.T., and S.C. analyzed data; N.M.B., M.A.A., B.O., and S.C. interpreted results of experiments; N.M.B. prepared figures; N.M.B. and S.C. drafted manuscript; N.M.B., M.A.A., C.G.T., X.S., S.D., G.R.-C., B.O., W.D.G., and S.C. approved final version of manuscript; M.A.A., B.O., and S.C. edited and revised manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. N. Paolocci for comments and fruitful discussions, Dr. A. Sidor for expert assistance in cell handling, and Dr. J. M. Kembro for help with data processing.

Present address of C. G. Tocchetti: Dept. Translational Medical Sciences, Div. of Internal Medicine, Federico II University, Naples, Italy.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson EJ, Lustig ME, Boyle KE, Woodlief TL, Kane DA, Lin CT, Price JW 3rd Kang L, Rabinovitch PS, Szeto HH, Houmard JA, Cortright RN, Wasserman DH, Neufer PD. Mitochondrial H2O2 emission and cellular redox state link excess fat intake to insulin resistance in both rodents and humans. J Clin Invest 119: 573–581, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aon MA, Cortassa S, Maack C, O′Rourke B. Sequential opening of mitochondrial ion channels as a function of glutathione redox thiol status. J Biol Chem 282: 21889–21900, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aon MA, Cortassa S, O′Rourke B. Redox-optimized ROS balance: a unifying hypothesis. Biochim Biophys Acta 1797: 865–877, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aon MA, Cortassa S, Wei AC, Grunnet M, O′Rourke B. Energetic performance is improved by specific activation of K+ fluxes through KCa channels in heart mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta 1797: 71–80, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aon MA, Stanley BA, Sivakumaran V, Kembro JM, O′Rourke B, Paolocci N, Cortassa S. Glutathione/thioredoxin systems modulate mitochondrial H2O2 emission: an experimental-computational study. J Gen Physiol 139: 479–491, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bers DM. Altered cardiac myocyte Ca regulation in heart failure. Physiology (Bethesda) 21: 380–387, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bing RJ, Michal G. Myocardial efficiency. Ann N Y Acad Sci 72: 555–558, 1959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boardman N, Hafstad AD, Larsen TS, Severson DL, Aasum E. Increased O2 cost of basal metabolism and excitation-contraction coupling in hearts from type 2 diabetic mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 296: H1373–H1379, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bonen A, Holloway GP, Tandon NN, Han XX, McFarlan J, Glatz JF, Luiken JJ. Cardiac and skeletal muscle fatty acid transport and transporters and triacylglycerol and fatty acid oxidation in lean and Zucker diabetic fatty rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 297: R1202–R1212, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boudina S, Abel ED. Diabetic cardiomyopathy, causes and effects. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 11: 31–39, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brownlee M. Biochemistry and molecular cell biology of diabetic complications. Nature 414: 813–820, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Buchanan J, Mazumder PK, Hu P, Chakrabarti G, Roberts MW, Yun UJ, Cooksey RC, Litwin SE, Abel ED. Reduced cardiac efficiency and altered substrate metabolism precedes the onset of hyperglycemia and contractile dysfunction in two mouse models of insulin resistance and obesity. Endocrinology 146: 5341–5349, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burgoyne JR, Mongue-Din H, Eaton P, Shah AM. Redox signaling in cardiac physiology and pathology. Circ Res 111: 1091–1106, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Burgoyne JR, Oka S, Ale-Agha N, Eaton P. Hydrogen peroxide sensing and signaling by protein kinases in the cardiovascular system. Antioxid Redox Signal 18: 1042–1052, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carley AN, Severson DL. Fatty acid metabolism is enhanced in type 2 diabetic hearts. Biochim Biophys Ccta 1734: 112–126, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chatham JC, Forder JR. Relationship between cardiac function and substrate oxidation in hearts of diabetic rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 273: H52–H58, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chatham JC, Seymour AM. Cardiac carbohydrate metabolism in Zucker diabetic fatty rats. Cardiovasc Res 55: 104–112, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chokshi A, Drosatos K, Cheema FH, Ji R, Khawaja T, Yu S, Kato T, Khan R, Takayama H, Knoll R, Milting H, Chung CS, Jorde U, Naka Y, Mancini DM, Goldberg IJ, Schulze PC. Ventricular assist device implantation corrects myocardial lipotoxicity, reverses insulin resistance, and normalizes cardiac metabolism in patients with advanced heart failure. Circulation 125: 2844–2853, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cook SA, Varela-Carver A, Mongillo M, Kleinert C, Khan MT, Leccisotti L, Strickland N, Matsui T, Das S, Rosenzweig A, Punjabi P, Camici PG. Abnormal myocardial insulin signalling in type 2 diabetes and left-ventricular dysfunction. Eur Heart J 31: 100–111, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cortassa S, Aon MA, O′Rourke B, Jacques R, Tseng HJ, Marban E, Winslow RL. A computational model integrating electrophysiology, contraction, and mitochondrial bioenergetics in the ventricular myocyte. Biophys J 91: 1564–1589, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cortassa S, O′Rourke B, Aon MA. Redox-optimized ROS balance and the relationship between mitochondrial respiration and ROS. Biochim Biophys Acta 1837: 287–295, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davila-Roman VG, Vedala G, Herrero P, de las Fuentes L, Rogers JG, Kelly DP, Gropler RJ. Altered myocardial fatty acid and glucose metabolism in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 40: 271–277, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fisher-Wellman KH, Neufer PD. Linking mitochondrial bioenergetics to insulin resistance via redox biology. Trends Endocrinol Metab 23: 142–153, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Forcheron F, Basset A, Abdallah P, Del Carmine P, Gadot N, Beylot M. Diabetic cardiomyopathy: effects of fenofibrate and metformin in an experimental model—the Zucker diabetic rat. Cardiovasc Diabetol 8: 16, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fu Q, Xu B, Liu Y, Parikh D, Li J, Li Y, Zhang Y, Riehle C, Zhu Y, Rawlings T, Shi Q, Clark RB, Chen X, Abel ED, Xiang YK. Insulin inhibits cardiac contractility by inducing a Gi-biased beta2-adrenergic signaling in hearts. Diabetes 63: 2676–2689, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giacco F, Brownlee M. Oxidative stress and diabetic complications. Circ Res 107: 1058–1070, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Haim TE, Wang W, Flagg TP, Tones MA, Bahinski A, Numann RE, Nichols CG, Nerbonne JM. Palmitate attenuates myocardial contractility through augmentation of repolarizing Kv currents. J Mol Cell Cardiol 48: 395–405, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harmancey R, Taegtmeyer H. The complexities of diabetic cardiomyopathy: lessons from patients and animal models. Curr Diab Rep 8: 243–248, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.How OJ, Aasum E, Severson DL, Chan WY, Essop MF, Larsen TS. Increased myocardial oxygen consumption reduces cardiac efficiency in diabetic mice. Diabetes 55: 466–473, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Howarth FC, Qureshi MA, Hassan Z, Al Kury LT, Isaev D, Parekh K, Yammahi SR, Oz M, Adrian TE, Adeghate E. Changing pattern of gene expression is associated with ventricular myocyte dysfunction and altered mechanisms of Ca2+ signalling in young type 2 Zucker diabetic fatty rat heart. Exp Physiol 96: 325–337, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Howarth FC, Qureshi MA, Hassan Z, Isaev D, Parekh K, John A, Oz M, Raza H, Adeghate E, Adrian TE. Contractility of ventricular myocytes is well preserved despite altered mechanisms of Ca2+ transport and a changing pattern of mRNA in aged type 2 Zucker diabetic fatty rat heart. Mol Cell Biochem 361: 267–280, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang JM, Xian H, Bacaner M. Long-chain fatty acids activate calcium channels in ventricular myocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89: 6452–6456, 1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hue L, Taegtmeyer H. The Randle cycle revisited: a new head for an old hat. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 297: E578–E591, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Janssen PM, Hunter WC. Force, not sarcomere length, correlates with prolongation of isosarcometric contraction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 269: H676–H685, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kannel WB, McGee DL. Diabetes and cardiovascular disease. The Framingham study. JAMA 241: 2035–2038, 1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kembro JM, Aon MA, Winslow RL, O′Rourke B, Cortassa S. Integrating mitochondrial energetics, redox and ROS metabolic networks: a two-compartment model. Biophys J 104: 332–343, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lagadic-Gossmann D, Buckler KJ, Le Prigent K, Feuvray D. Altered Ca2+ handling in ventricular myocytes isolated from diabetic rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 270: H1529–H1537, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lionetti V, Stanley WC, Recchia FA. Modulating fatty acid oxidation in heart failure. Cardiovasc Res 90: 202–209, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lopaschuk GD, Ussher JR, Folmes CD, Jaswal JS, Stanley WC. Myocardial fatty acid metabolism in health and disease. Physiol Rev 90: 207–258, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mazumder PK, O′Neill BT, Roberts MW, Buchanan J, Yun UJ, Cooksey RC, Boudina S, Abel ED. Impaired cardiac efficiency and increased fatty acid oxidation in insulin-resistant ob/ob mouse hearts. Diabetes 53: 2366–2374, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mellor KM, Ritchie RH, Delbridge LM. Reactive oxygen species and insulin-resistant cardiomyopathy. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 37: 222–228, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Neubauer S. The failing heart—an engine out of fuel. N Engl J Med 356: 1140–1151, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nichols GA, Hillier TA, Erbey JR, Brown JB. Congestive heart failure in type 2 diabetes: prevalence, incidence, and risk factors. Diabetes Care 24: 1614–1619, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nickel A, Loffler J, Maack C. Myocardial energetics in heart failure. Basic Res Cardiol 108: 358, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rindler PM, Crewe CL, Fernandes J, Kinter M, Szweda LI. Redox regulation of insulin sensitivity due to enhanced fatty acid utilization in the mitochondria. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 305: H634–H643, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rosca MG, Vazquez EJ, Kerner J, Parland W, Chandler MP, Stanley W, Sabbah HN, Hoppel CL. Cardiac mitochondria in heart failure: decrease in respirasomes and oxidative phosphorylation. Cardiovasc Res 80: 30–39, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schilling JD, Mann DL. Diabetic cardiomyopathy: bench to bedside. Heart Fail Clin 8: 619–631, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shen X, Bhatt N, Xu J, Meng T, Aon MA, O′Rourke B, Berkowitz DE, Cortassa S, Gao WD. Effect of isoflurane on myocardial energetic and oxidative stress in cardiac muscle from zucker diabetic Fatty rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 349: 21–28, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stanley BA, Sivakumaran V, Shi S, McDonald I, Lloyd D, Watson WH, Aon MA, Paolocci N. Thioredoxin reductase-2 is essential for keeping low levels of H2O2 emission from isolated heart mitochondria. J Biol Chem 286: 33669–33677, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stowe DF, Fujita S, An J, Paulsen RA, Varadarajan SG, Smart SC. Modulation of myocardial function and [Ca2+] sensitivity by moderate hypothermia in guinea pig isolated hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 277: H2321–H2332, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tocchetti CG, Caceres V, Stanley BA, Xie C, Shi S, Watson WH, O′Rourke B, Spadari-Bratfisch RC, Cortassa S, Akar FG, Paolocci N, Aon MA. GSH or palmitate preserves mitochondrial energetic/redox balance, preventing mechanical dysfunction in metabolically challenged myocytes/hearts from type 2 diabetic mice. Diabetes 61: 3094–3105, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tong CW, Gaffin RD, Zawieja DC, Muthuchamy M. Roles of phosphorylation of myosin binding protein-C and troponin I in mouse cardiac muscle twitch dynamics. J Physiol 558: 927–941, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ussher JR, Jaswal JS, Lopaschuk GD. Pyridine nucleotide regulation of cardiac intermediary metabolism. Circ Res 111: 628–641, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang P, Lloyd SG, Chatham JC. Impact of high glucose/high insulin and dichloroacetate treatment on carbohydrate oxidation and functional recovery after low-flow ischemia and reperfusion in the isolated perfused rat heart. Circulation 111: 2066–2072, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang P, Lloyd SG, Zeng H, Bonen A, Chatham JC. Impact of altered substrate utilization on cardiac function in isolated hearts from Zucker diabetic fatty rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 288: H2102–H2110, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wu X, Zhu L, Zilbering A, Mahadev K, Motoshima H, Yao J, Goldstein BJ. Hyperglycemia potentiates H2O2 production in adipocytes and enhances insulin signal transduction: potential role for oxidative inhibition of thiol-sensitive protein-tyrosine phosphatases. Antioxid Redox Signal 7: 526–537, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xu X, Colecraft HM. Primary culture of adult rat heart myocytes. J Vis Exp 28: 1308, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yoshinari O, Shiojima Y, Igarashi K. Anti-obesity effects of onion extract in Zucker diabetic fatty rats. Nutrients 4: 1518–1526, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Young ME, Guthrie PH, Razeghi P, Leighton B, Abbasi S, Patil S, Youker KA, Taegtmeyer H. Impaired long-chain fatty acid oxidation and contractile dysfunction in the obese Zucker rat heart. Diabetes 51: 2587–2595, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang L, Cannell MB, Phillips AR, Cooper GJ, Ward ML. Altered calcium homeostasis does not explain the contractile deficit of diabetic cardiomyopathy. Diabetes 57: 2158–2166, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]