Abstract

Objective:

In the present study, we investigated the efficacy of a methanol extract from Impatiens balsamina L. (MEIB) against HSC-2 human oral cancer cells.

Materials and Methods:

The anti-cancer efficacies of MEIB were performed by methanethiosulfonate assay, phospho-kinase array, Western blot, 4’-6-diamidino-2-phenylindole staining, trypan blue exclusion assay and 5,5’,6,6’-tetrachloro-1,1’,3,3’-tetraethylbenzimidazolylcarbocyanine iodide assay.

Results:

MEIB decreased the cell viability of HSC-2 cells. According to phospho-kinase arrays, MEIB markedly activated AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) signaling, but inactivated mammalian target of rapamycin signaling. MEIB induced apoptosis as evidenced by activation of caspase-3, poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase cleavage and nuclear condensation. In addition, AMPK activation by two known activators (5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-ribofuranoside and metformin) decreased cell viability and induced apoptosis. Moreover, MEIB increased the expression levels of mitochondria-related proteins (t-Bid, Bak and Bad), which contributed to the disruption of mitochondrial membrane potential, cytochrome C release and activation of caspase-9. Metformin also increased t-Bid expression and the subsequent release of cytochrome C into the cytosol.

Conclusion:

These results suggest that MEIB may be of therapeutic value for treating oral cancer and that its mechanism of action occurs through AMPK and t-Bid.

Keywords: AMP-activated protein kinase, apoptosis, Impatiens balsamina L, oral cancer, t-Bid

INTRODUCTION

AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) is a heterotrimeric serine/threonine kinase, that plays an essential role as a cellular energy sensor.[1] Under conditions of low intracellular adenosine triphosphate (ATP) levels resulting from nutrient deprivation, hypoxia, gluconeogenesis or fatty acid synthesis, AMPK is activated, thereby triggering an increase in cellular processes that generate intracellular ATP and a decrease in ATP-consuming processes that are not immediately necessary for cell survival.[2] AMPK is also activated by phosphorylation on Thr172, a residue located in the activation loop of the α subunit, by two distinct upstream kinases: Liver kinase B1 (LKB1) and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase kinase β.[3] A recent study has shown that phosphorylation of AMPK (p-AMPK) was significantly suppressed in breast cancer tissue compared with normal tissue; furthermore, dysregulated production of p-AMPK was correlated with higher histological grade and axillary node metastasis.[4] Knockdown of AMPK in normal cells prohibited them from inhibiting proliferation signals under nutrient stress, suggesting that reduced AMPK activity contributed to tumorigenesis.[5] Previous studies have also reported that several AMPK activators, such as 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-ribofuranoside (AICAR) and phenformin, could potentially be used as chemotherapeutic drugs for cancer patients because they enhanced growth inhibition, cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in multiple cancer cell lines and xenograft models.[6,7] In particular, metformin reduced the survival and tumorigenic potential of oral malignant lesions by inhibiting carcinogen-induced oral premalignant lesions.[8] Metformin has also been shown to decrease cell proliferation in oral cancer cells by blocking cell cycle progression and inducing apoptosis.[9] Moreover, activation of the LKB1/AMPK pathway has been shown to be required for apoptosis and autophagy in β-catenin-silenced head and neck cancer cells.[10] Thus, AMPK seems to be a promising therapeutic strategy for combating oral cancer. In the present study, we demonstrated that methanol extract from Impatiens balsamina (MEIB) exerts apoptotic effects and that the mechanism of MEIB involves AMPK in HSC-2 human oral cancer cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chemicals and antibodies

Methanol extract from I. balsamina was kindly provided by Prof. Ki-Han Kwon in Gwangju University (Gwangju, Korea). 4’-6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) fluorescent nuclear dye, AICAR and metformin were supplied by Sigma-Aldrich (Louis, MO, USA). Antibodies against p-AMPK (T172), AMPK, phosphorylation of mammalian target of rapamycin (p-mTOR) (S2448), mTOR, p-p70S6 kinase (T389), p70S6 kinase, p-p38 (T180/Y182), p38, p-ERK (T202/Y204, T185/Y187), extracellular-signal-regulated kinases (ERK), cleaved caspase-9, cleaved caspase-3, Bid, Bak, Bad, Bax, Puma, Bim, Bcl-xL, Mcl-1 and Bcl-2 were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc., (Charlottesville, VA, USA). Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) and cytochrome C antibodies were purchased from BD Pharmingen™ (San Jose, CA, USA). Actin and α-tubulin antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Cox 4 antibody was acquired from Abcam (Cambridge, UK).

Cell culture and chemical treatment

HSC-2 cells were kindly provided by Hokkaido University (Hokkaido, Japan). Cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics in a humidified incubator at 37°C and 5% CO2.

Methanethiosulfonate assay

The effect of MEIB on cell viability was determined with an methanethiosulfonate (MTS) assay according to a previous study.[11] Briefly, cells were seeded in 96-well plates and then incubated with 60 μg/ml of MEIB for 24 h. MTS solution was added to each well and cells were maintained for 2 h. Absorbance was then measured with a Chameleon microplate reader (Hidex, Turku, Finland) at 482 nm.

Human phospho-kinase proteome profiling

HSC-2 cells were treated with 60 μg/ml of MEIB for 12 h and subsequently lysed. The phosphorylation levels of 46 kinases in the cell lysates were detected using a human phospho-kinase array kit (R and D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) according to a previous study.[12] Briefly, membranes were blocked with array buffer for 1 h at RT, after which time the cell lysates were added and maintained overnight at 4°C. Incubation with antibody cocktails was then carried out for 2 h at RT. Membranes were then washed and incubated with array buffer containing diluted streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) for 30 min at RT. Each capture spot corresponding to the amount of phosphorylated protein bound was detected with enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) Western Blotting Luminol Reagent (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc, Santa Cruz, CA, USA).

Western blot analysis

Whole-cell lysates were quantified using a DC Protein Assay Kit (BIO-RAD Laboratories, Madison, WI, USA). The procedure was described in a previous study.[13] Briefly, samples containing equal amounts of protein were separated by sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and then transferred to Immun-Blot™ polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (BIO-RAD Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). Membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk in TBST at RT for 2 h, and maintained overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies. Incubation with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies was then carried out at RT for 2 h. Antibody-bound proteins were detected using ECL Western Blotting Luminol Reagent.

Detection of nuclear morphological changes

Detection of chromatin condensation and nuclear fragmentation in the nuclei of apoptotic cells was performed by DAPI staining as previously described.[14] Cells were treated with MEIB, AICAR or metformin, and then harvested by trypsinization. Detached cells were fixed in 100% methanol at RT for 10 min, and then deposited on slides. Cells were stained with DAPI solution (2 μg/ml) and then cell morphology was observed under a fluorescence microscope.

Trypan blue exclusion assay

Cells were treated with AICAR or metformin for 24 h, stained with trypan blue (Gibco, Paisley, UK), Cells were treated with AICAR or metformin for 24 h, stained with trypan blue (0.4%), and then viable cells were counted using a hemocytometer as previously described.[15]

Detection of mitochondrial membrane potential with 5,5’,6,6’-tetrachloro-1,1’,3,3’-tetraethy-lbenzimidazolylcarbocyanine iodide

Mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) was measured using a 5,5’,6,6’-tetrachloro-1,1’,3,3’-tetraethylbenzimidazolylcarbocyanine iodide (JC-1) (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA). Briefly, cells were treated with 60 μg/ml of MEIB for 24 h and then harvested by trypsinization. Cell pellets were stained with JC-1 solution for 15 min in a 37°C incubator. Following a centrifugation step at 400 g for 5 min at RT, cell pellets were washed with 1X assay buffer. Pellets were resuspended in 1X assay buffer. The fluorescence intensity was measured using a fluorescence microplate reader equipped with the appropriate excitation and emission filters (Hidex, Turku, Finland) as previously described.[16]

Preparation of cytosolic fraction

The procedures for preparation of cytosolic fraction were described in a previous study.[13] Briefly, cell pellets were resuspended for 1 min at RT in plasma membrane extraction buffer containing 0.05% digitonin. Following a centrifugation step at 15,000 g at 4°C for 5 min, supernatant was separated from pellets consisting of cellular debris. The supernatant containing cytosolic proteins was collected.

Statistical analysis

Student's t-test was used to determine the significance of differences between the control and treatment groups; P < 0.05 were considered significant.

RESULTS

Methanol extract from Impatiens balsamina activates AMP-activated protein kinase to mediate growth inhibition and apoptosis in HSC-2 human oral cancer cells

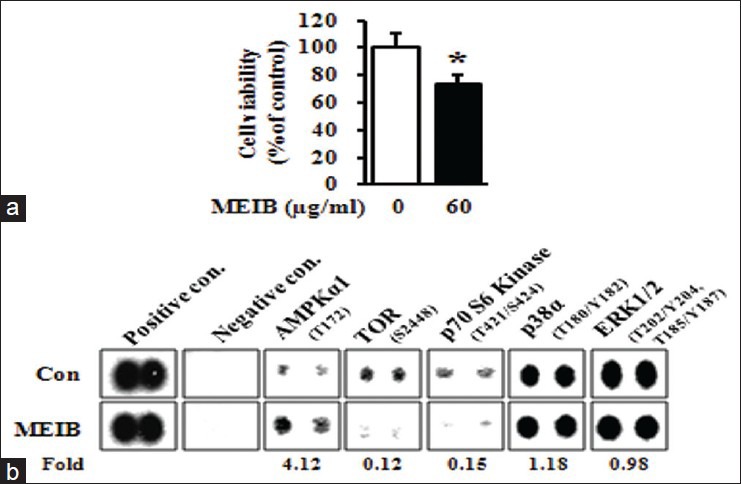

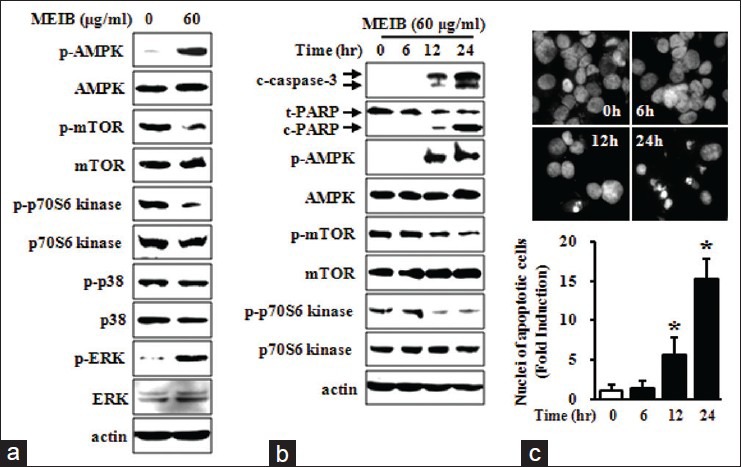

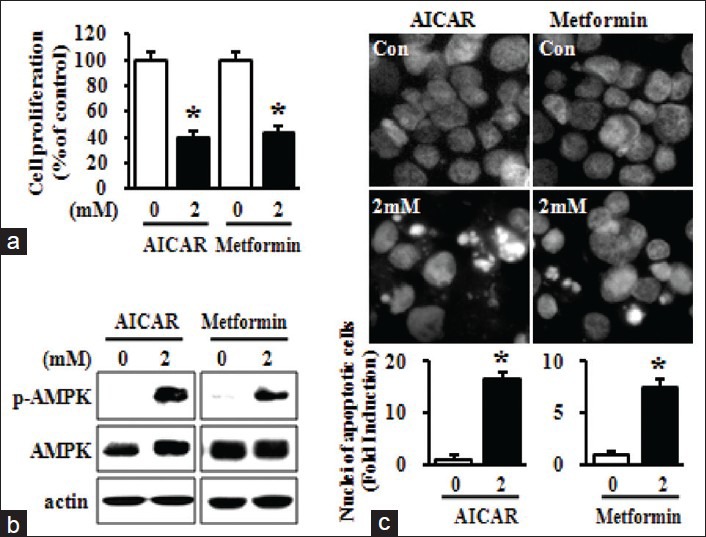

To investigate the effects of MEIB on cancer cell growth, we first performed MTS assays on MEIB-treated HSC-2 human oral cancer cells. As shown in Figure 1a, exposure of cells to MEIB (60 μg/ml) for 24 h resulted in a reduction of cell viability. To determine the primary signaling pathway affected by MEIB, we evaluated its effect on multiple protein kinases using a human phospho-kinase array comprising 46 kinases. The arrays showed that MEIB increased p-AMPK by 4.12-fold compared with the control group [Figure 1b]. We also found that MEIB decreased phosphorylation of TOR by 0.12-fold and p70S6 kinase by 0.15-fold among the AMPK-related proteins. In contrast, MEIB had almost no effect on the phosphorylation of p38 (1.18-fold change) and ERK (0.98-fold change). To validate the phospho-kinase array data with a complementary technique, we performed Western blot analysis. As shown in Figure 2a, MEIB caused a striking up-regulation of p-AMPK and significant reductions of p-mTOR and p-p70S6 kinase even though it did not have a significant effect on either p-p38 or p-ERK. To further confirm that the AMPK signaling pathway dominates the cellular response to MEIB, cells were treated with 60 μg/ml of MEIB for different time points. These time-course experiments showed that induction of p-AMPK by MEIB resulted in inactivation of mTOR signaling as manifested by decreased p-mTOR and p-p70S6 kinase in a time-dependent manner, ultimately resulting in caspase-3 activation and PARP cleavage [Figure 2b]. We also found that MEIB caused a discernible induction of apoptotic features such as chromatin condensation and nuclear fragmentation [Figure 2c]. These results suggest that AMPK activation may contribute to MEIB-induced growth inhibition and apoptosis. To further confirm the role of AMPK activation in growth inhibition and apoptosis in HSC-2 cells, we examined the anti-cancer effects of AICAR and metformin known, two known activators of AMPK on HSC-2 cells. As shown in Figure 3a demonstrates, both AICAR and metformin significantly reduced cell growth. We also found that induction of AMPK activation by either AICAR or metformin resulted in marked increases of chromatin condensation and nuclear fragmentation [Figure 3b and c]. Thus, we suggest that AMPK activation is required for MEIB-induced growth inhibition and apoptosis induction in HSC-2 human oral cancer cells.

Figure 1.

Methanol extract from Impatiens balsamina (MEIB) regulates the AMP-activated protein kinase/mammalian target of rapamycin/p70S6K signaling axis. (a) HSC-2 cells were treated with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or 60 μg/ml of MEIB for 24 h. The effect of MEIB on cell viability was determined using a methanethiosulfonate assay. The graph was expressed the mean ± standard deviation of triplicate experiments. *P < 0.05 compared with the DMSO-treated group; (b) HSC-2 cells treated with 60 μg/ml of MEIB for 12 h were harvested and analyzed by human phospho-kinase array

Figure 2.

AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) activation is required for methanol extract from Impatiens balsamina (MEIB) induced apoptosis. HSC-2 cells were treated with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or 60 μg/ml of MEIB for 24 h. (a) Whole-cell lysates were analyzed by Western blot analysis using antibodies against phosphorylation of AMPK (p-AMPK), AMPK, phosphorylation of mammalian target of rapamycin (p-mTOR), mTOR, p-p70S6 kinase, p70S6 kinase, p-p38, p38, p-ERK and ERK. Actin was used as a loading control, (b) HSC-2 cells treated with 60 μg/ml of MEIB were harvested at different time points (0, 6, 12 or 24 h), and analyzed by Western blot analysis using antibodies against p-AMPK, AMPK, p-mTOR, mTOR, p-p70S6 kinase, p70S6 kinase, cleaved caspase-3 and cleaved poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. (c) The apoptotic effect of MEIB was invesitgated by 4’-6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining. Nuclear condensation and DNA fragmentation were initially observed by fluorescence microscopy (×400); subsequently, DAPI-stained cells were quantified. The numbers of apoptotic cells were expressed as the means ± standard deviation of triplicate experiments. *P < 0.05 compared with the DMSO-treated group

Figure 3.

AMP-activated protein kinase activation by 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-ribofuranoside (AICAR) and metformin contributes to growth inhibition and apoptosis induction in HSC-2 cells. HSC-2 cells were treated with either dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or 2 mM of AICAR or metformin for 24 h. (a) The effects of AICAR and metformin on cell growth were determined using trypan blue exclusion assays. The graph was expressed the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of triplicate experiments. *P < 0.05 compared with the DMSO-treated group; (b) The whole-cell lysates were analyzed by Western blot analysis using antibodies against phosphorylation of AMPK and AMP-activated protein kinase; (c) The apoptotic effects of AICAR and metformin were observed by 4’-6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining. Nuclear condensation and DNA fragmentation were initially observed by fluorescence microscopy (magnification, ×400), and then DAPI-stained cells were quantified. Numbers of apoptotic cells were expressed the mean ± SD of triplicate experiments. *P < 0.05 compared with the DMSO-treated group

AMP-activated protein kinase activation by methanol extract from Impatiens balsamina is responsible for t-Bid-mediated apoptosis

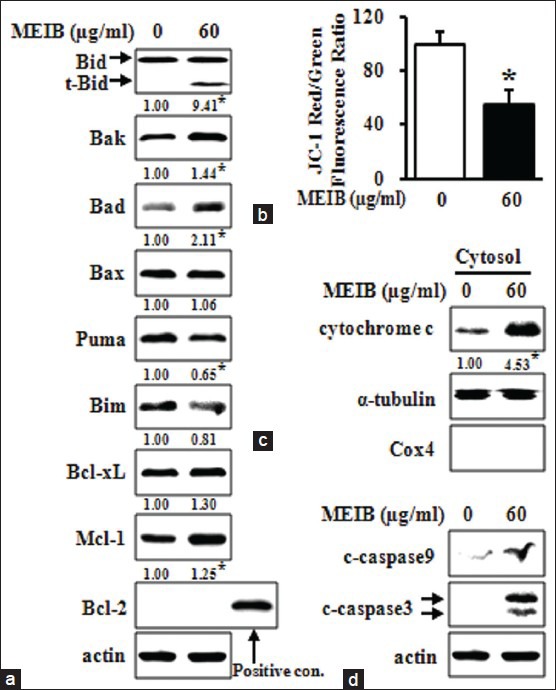

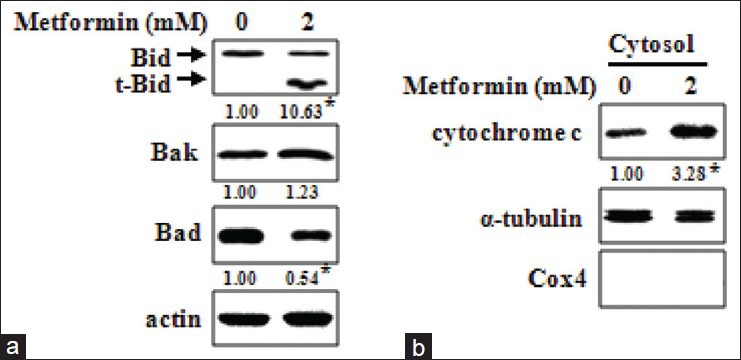

To determine whether AMPK activation by MEIB affects Bcl-2 family proteins, we examined protein levels of Bid, Bak, Bad, Bax, Puma, Bim, Bcl-xL, Mcl-1 and Bcl-2 by Western blot analysis. Figure 4a showed that MEIB increased the protein levels of t-Bid, Bak and Bad; however, MEIB did not significantly affect the levels of any of the other proteins investigated here. Since many Bcl-2 family proteins play a role in the regulation of MMP, we investigated the effects of MEIB on MMP using a fluorescent cationic dye, JC-1. These experiments showed that MEIB induced a marked reduction in the JC-1 red/green fluorescence ratio [Figure 4b], indicating that MEIB treatment disrupted the MMP. We next investigated whether disruption of MMP was accompanied by release of cytochrome C into the cytosol. Figure 4c and d showed that MEIB treatment resulted in a pronounced increase of cytochrome C release into the cytosol, resulting in the activation of caspase-9 and caspase-3. These results suggest that MEIB-induced apoptosis may be mediated by Bcl-2 family proteins and their downstream signaling events, including cytochrome C release and caspase activation. To further confirm the functional significance of AMPK in the regulation of t-Bid, Bak and Bad in MEIB-induced apoptosis, we examined the effect of metformin. As shown in Figure 5a, metformin markedly increased t-Bid expression, but Bak and Bad were not affected. We also found that metformin increased release of cytochrome C into cytosol [Figure 5b], implying that t-Bid is a main downstream target of MEIB-induced AMPK activation.

Figure 4.

Methanol extract from Impatiens balsamina (MEIB) disrupts mitochondrial membrane potential by regulating the expression of Bcl-2 family proteins. HSC-2 cells were treated with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or 60 μg/ml of MEIB for 24 h. (a) The whole-cell lysates were analyzed by Western blot analysis using antibodies against t-Bid, Bak, Bad, Bax, Puma, Bim, Bcl-xL, Mcl-1 and Bcl-2. *P < 0.05 compared with the DMSO-treated group; (b) Mitochondrial membrane potential was assessed using a 5,5’,6,6’-tetrachloro-1,1’,3,3’-tetraethylbenzimidazolyl carbocyanine iodide assay. The fluorescence intensity of Red/Green expressed as the means ± standard deviation of triplicate experiments. *P < 0.05 compared with the DMSO-treated group; (c) detection of cytochrome C in cytosolic fractions by Western blot analysis. Cox4 and α-tubulin were used as a fraction marker for mitochondrial and cytosolic fraction, respectively. *P < 0.05 compared with the DMSO-treated group, (d) cleaved caspase-9 and cleaved caspase-3 were detected by Western blot analysis

Figure 5.

AMP-activated protein kinase activation by metformin enhances t-Bid expression, which is followed by cytochrome C release. (a) HSC-2 cells were treated with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or 2 mM of metformin for 24 h. Whole-cell lysates were analyzed by Western blot analysis using antibodies against t-Bid, Bak and Bad. *P < 0.05 compared with the DMSO-treated group; (b) The presence of cytochrome C in cytosolic fraction was detected by Western blot anlaysis. Cox4 and α-tubulin were used as fraction markers for the mitochondrial and cytosolic fraction, respectively. *P < 0.05 compared with the DMSO-treated group

DISCUSSION

Although many conventional therapeutic advances have been made for cancer patients, they are not all necessarily clinically applicable because of their serious side effects. Hence, there is a constant demand for the development of more effective and less toxic anti-cancer drugs. Previous studies have reported that many anti-cancer drugs are discovered directly from natural products or by structural modification of existing natural products;[17] thus, natural products are likely a promising source for novel anti-cancer drugs. In practice, many natural products originating from plants, fruits, vegetables, animals and microbes have been shown to have chemopreventive and chemotherapeutic activities, with low levels of toxicity.[18,19] Therefore, exploiting natural products with anti-cancer properties is an ideal strategy for developing more effective and less toxic anti-cancer drugs. I. balsamina L., is a traditional medicinal plant that possesses potential antioxidant and antimicrobial properties.[20] It has been also reported that a number of active compounds isolated from I. balsamina L. including 2-methoxy-1,4-naphthoquinone and kaempferol, exhibit strong antibacterial and antitumor activities.[21,22] However, there are no reports to date regarding the anti-cancer effects of I. balsamina L. and the molecular mechanism by which it acts on cancer cells. In the present study, we demonstrated that MEIB exerts anti-cancer activities on HSC-2 human oral cancer cells.

Dysregulation of AMPK signaling contributes to the pathogenesis of many types of cancer.[1] Interestingly, natural products derived from plant sources have been shown to activate AMPK, and this activity was associated with their anti-cancer properties. Bitter melon juice has been shown to induce apoptosis through an intrinsic pathway in pancreatic cancer cells and the efficacy of this induction has been shown to require AMPK activation.[23] Honokiol, a compound isolated from Magnolia grandiflora, also modulated the LKB1/AMPK/p70S6K signaling pathway, thereby suppressing migration and invasion.[24] Furthermore, plumbagin has also been shown to enhance AMPK activity resulting in inhibiting the mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1)/Bcl-2 axis and stimulating JNK/p53 axis through apoptosis signal regulating kinase 1 (ASK1)/tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 2 association, leading to growth inhibition and apoptosis induction.[25] In light of the potential effects of AMPK activation by natural products, we hypothesized that enhancement of AMPK activation could constitute an attractive therapeutic strategy for treating cancer. In keeping with this notion, we found that MEIB significantly induced apoptosis concurrently with AMPK activation. In addition, two pharmacological AMPK activators, AICAR and metformin, decreased cell growth and induced apoptosis. These results provide evidence that AMPK activation by MEIB can inhibit cell growth and induce apoptosis in HSC-2 human oral cancer cells.

Bcl-2 family proteins are key regulators in mitochondria-mediated apoptosis, functioning to regulate the balance between pro-survival and pro-apoptotic proteins.[26] In particular, several natural products have been demonstrated to trigger disruption of MMP and cytochrome C release through their effects on Bcl-2 family proteins, thereby resulting in apoptosis induction.[27] In the present study, we observed that MEIB increased the expression levels of t-Bid, Bak and Bad; however, MEIB did not have a significant effect on any other Bcl-2 family proteins. In addition, MEIB disrupted MMP and caused subsequent release of cytochrome C into the cytoplasm, resulting in activation of the caspase cascade. Previous studies have reported that expression of several Bcl-2 family proteins is required for activation of AMPK.[28,29,30] To investigate whether AMPK activation by MEIB was involved in an increase in t-Bid, Bak and Bad expression levels, metformin was utilized. We demonstrated that metformin only increased the expression level of t-Bid, and that this effect was sufficient to cause release of cytochrome C into the cytosol. These results support a model in which MEIB-induced AMPK activation is sufficient for up-regulating t-Bid expression levels, thereby driving apoptotic process. This study provides evidence that MEIB exerts anti-cancer action on HSC-2 human oral cancer cells. Molecular studies revealed that MEIB enhances AMPK activation thereby inducing apoptosis in a manner involving regulation of t-Bid expression. Taken together, these results suggest that MEIB is a promising chemotherapeutic drug candidate for treating oral cancer.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (2012003731).

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Luo Z, Saha AK, Xiang X, Ruderman NB. AMPK, the metabolic syndrome and cancer. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2005;26:69–76. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fogarty S, Hardie DG. Development of protein kinase activators: AMPK as a target in metabolic disorders and cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1804:581–91. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2009.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luo Z, Zang M, Guo W. AMPK as a metabolic tumor suppressor: Control of metabolism and cell growth. Future Oncol. 2010;6:457–70. doi: 10.2217/fon.09.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hadad SM, Baker L, Quinlan PR, Robertson KE, Bray SE, Thomson G, et al. Histological evaluation of AMPK signalling in primary breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2009;9:307. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-9-307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fox MM, Phoenix KN, Kopsiaftis SG, Claffey KP. AMP-Activated Protein Kinase a 2 Isoform suppression in primary breast cancer alters AMPK growth control and apoptotic signaling. Genes Cancer. 2013;4:3–14. doi: 10.1177/1947601913486346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garcia-Gil M, Pesi R, Perna S, Allegrini S, Giannecchini M, Camici M, et al. 5’-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide riboside induces apoptosis in human neuroblastoma cells. Neuroscience. 2003;117:811–20. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00836-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Appleyard MV, Murray KE, Coates PJ, Wullschleger S, Bray SE, Kernohan NM, et al. Phenformin as prophylaxis and therapy in breast cancer xenografts. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:1117–22. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vitale-Cross L, Molinolo AA, Martin D, Younis RH, Maruyama T, Patel V, et al. Metformin prevents the development of oral squamous cell carcinomas from carcinogen-induced premalignant lesions. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2012;5:562–73. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sikka A, Kaur M, Agarwal C, Deep G, Agarwal R. Metformin suppresses growth of human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma via global inhibition of protein translation. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:1374–82. doi: 10.4161/cc.19798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang HW, Lee YS, Nam HY, Han MW, Kim HJ, Moon SY, et al. Knockdown of ß-catenin controls both apoptotic and autophagic cell death through LKB1/AMPK signaling in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cell lines. Cell Signal. 2013;25:839–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang T, Hamza A, Cao X, Wang B, Yu S, Zhan CG, et al. A novel Hsp90 inhibitor to disrupt Hsp90/Cdc37 complex against pancreatic cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:162–70. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guo T, Lee SS, Ng WH, Zhu Y, Gan CS, Zhu J, et al. Global molecular dysfunctions in gastric cancer revealed by an integrated analysis of the phosphoproteome and transcriptome. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2011;68:1983–2002. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0545-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shin JA, Jung JY, Ryu MH, Safe S, Cho SD. Mithramycin A inhibits myeloid cell leukemia-1 to induce apoptosis in oral squamous cell carcinomas and tumor xenograft through activation of Bax and oligomerization. Mol Pharmacol. 2013;83:33–41. doi: 10.1124/mol.112.081364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghate NB, Hazra B, Sarkar R, Mandal N. Heartwood extract of Acacia catechu induces apoptosis in human breast carcinoma by altering bax/bcl-2 ratio. Pharmacogn Mag. 2014;10:27–33. doi: 10.4103/0973-1296.126654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramachandran S, Liu P, Young AN, Yin-Goen Q, Lim SD, Laycock N, et al. Loss of HOXC6 expression induces apoptosis in prostate cancer cells. Oncogene. 2005;24:188–98. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rai K, Matsui H, Kaneko T, Nagano Y, Shimokawa O, Udo J, et al. Lansoprazole inhibits mitochondrial superoxide production and cellular lipid peroxidation induced by indomethacin in RGM1 cells. J Clin Biochem Nutr. 2011;49:25–30. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.10-133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mondal S, Bandyopadhyay S, Ghosh MK, Mukhopadhyay S, Roy S, Mandal C. Natural products: Promising resources for cancer drug discovery. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2012;12:49–75. doi: 10.2174/187152012798764697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nobili S, Lippi D, Witort E, Donnini M, Bausi L, Mini E, et al. Natural compounds for cancer treatment and prevention. Pharmacol Res. 2009;59:365–78. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2009.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amin AR, Kucuk O, Khuri FR, Shin DM. Perspectives for cancer prevention with natural compounds. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2712–25. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.6235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Su BL, Zeng R, Chen JY, Chen CY, Guo JH, Huang CG. Antioxidant and antimicrobial properties of various solvent extracts from Impatiens balsamina L. stems. J Food Sci. 2012;77:C614–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2012.02709.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lim YH, Kim IH, Seo JJ. in vitro activity of kaempferol isolated from the Impatiens balsamina alone and in combination with erythromycin or clindamycin against Propionibacterium acnes. J Microbiol. 2007;45:473–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang YC, Lin YH. Anti-gastric adenocarcinoma activity of 2-Methoxy-1,4-naphthoquinone, an anti-Helicobacter pylori compound from Impatiens balsamina L. Fitoterapia. 2012;83:1336–44. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaur M, Deep G, Jain AK, Raina K, Agarwal C, Wempe MF, et al. Bitter melon juice activates cellular energy sensor AMP-activated protein kinase causing apoptotic death of human pancreatic carcinoma cells. Carcinogenesis. 2013;34:1585–92. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgt081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nagalingam A, Arbiser JL, Bonner MY, Saxena NK, Sharma D. Honokiol activates AMP-activated protein kinase in breast cancer cells via an LKB1-dependent pathway and inhibits breast carcinogenesis. Breast Cancer Res. 2012;14:R35. doi: 10.1186/bcr3128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen MB, Zhang Y, Wei MX, Shen W, Wu XY, Yao C, et al. Activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) mediates plumbagin-induced apoptosis and growth inhibition in cultured human colon cancer cells. Cell Signal. 2013;25:1993–2002. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2013.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Delft MF, Huang DC. How the Bcl-2 family of proteins interact to regulate apoptosis. Cell Res. 2006;16:203–13. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7310028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fulda S. Modulation of apoptosis by natural products for cancer therapy. Planta Med. 2010;76:1075–9. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1249961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Concannon CG, Tuffy LP, Weisová P, Bonner HP, Dávila D, Bonner C, et al. AMP kinase-mediated activation of the BH3-only protein Bim couples energy depletion to stress-induced apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 2010;189:83–94. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200909166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kilbride SM, Farrelly AM, Bonner C, Ward MW, Nyhan KC, Concannon CG, et al. AMP-activated protein kinase mediates apoptosis in response to bioenergetic stress through activation of the pro-apoptotic Bcl-2 homology domain-3-only protein BMF. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:36199–206. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.138107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yi B, Liu D, He M, Li Q, Liu T, Shao J. Role of the ROS/AMPK signaling pathway in tetramethylpyrazine-induced apoptosis in gastric cancer cells. Oncol Lett. 2013;6:583–89. doi: 10.3892/ol.2013.1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]