Abstract

Purpose:

To evaluate and modify the Randleman Ectasia Risk Score System for predicting post-laser in situ keratomileusis (LASIK) ectasia in patients with normal preoperative corneal topography.

Methods:

In this retrospective study we reviewed data from 136 eyes which had undergone LASIK including 34 ectatic and 102 normal eyes between 1999 and 2009. After determining the sensitivity and specificity of the Randleman system, a modified model was designed to predict the risk of post-LASIK corneal ectasia more accurately. Next, the sensitivity and specificity of this modified scoring system was determined and compared to that of the original scoring system.

Results:

In our sample, the sensitivity and specificity of the Randleman system was 70.1% and 50.5%, respectively. Our modified model included the following parameters: preoperative central corneal thickness, manifest refraction spherical equivalent, and maximum keratometry, as well as the number of months elapsed from surgery. Sensitivity and specificity rates of the modified system were 74.2% and 76.2%, respectively. The difference in receiver operating characteristic curves between the Randleman and modified scoring systems was statistically significant (P<0.001). The best sensitivity and specificity for our model occurred with a cumulative cutoff score of 4.00; a low risk was considered if the score was ≤4.00, and high risk was defined with a score > 4.00.

Conclusion:

Our modified ectasia risk scoring system for patients with normal corneal topography can predict post LASIK ectasia risk with acceptable sensitivity and specificity. However, there are still unidentified risk factors for which further studies are required.

Keywords: Ectasia, Randleman System, Topographically Normal Cornea

INTRODUCTION

Laser in situ keratomileusis (LASIK) is a type of refractive surgery with proven safety and efficacy;[1] however, it entails complications just like any other kind of surgical procedure. A rare, but serious complication is post LASIK ectasia,[2,3,4,5,6,7,8] which is characterized by progressive thinning and steepening of the cornea resulting in loss of best corrected visual acuity (BCVA). Post-LASIK ectasia is clinically important from two aspects: first, the condition is preventable[4] and secondly, most LASIK patients are young adults in whom the burden of the condition is greater.

Several studies have been conducted to determine risk factors for corneal ectasia[3,7,9,10] and devise corneal ectasia risk predicting scoring systems.[5,7] The Randleman Ectasia Risk Score System which was introduced[5] and validated[11] in 2008 considers five parameters including corneal topographic patterns, residual stromal bed thickness (RSB), age, central corneal thickness (CCT) and manifest refraction spherical equivalent (MRSE).[5]

The reported rates of refractive errors in Iranian adolescents and young adults are 49.6%,[12] 32.5%,[13] 21.8%[14] and 26%,[14] and the popularity of corrective surgeries is increasing.[15] This has provided an opportunity to study post-LASIK ectasia in an Iranian cohort. The present study was designed to retrospectively evaluate the Randleman Ectasia Risk Score System in Iranian patients, with a view to modify parameters and improve the predictive power if necessary.

METHODS

This retrospective study was conducted using available data from patients who had undergone LASIK between 1999 and 2009 at Noor Eye Clinics, Tehran, Iran. Ethical approval was obtained from Noor Ophthalmology Research Center Review Board. A total of 34 eyes with post LASIK ectasia were identified and selected as cases. For each case, three controls (102 eyes) were selected. Inclusion criteria for the control group were uncomplicated patients with at least 1-year of post-LASIK follow up and who had been operated at the same surgical facility during the same time period.

All LASIK procedures were performed using a mechanical microkeratome (Hansatome, Bausch and Lomb, Miami, FL, USA) with a 160 μm depth plate to create the corneal flap. Preoperative corneal thickness was measured by ultrasonic pachymetry. The diagnosis of corneal ectasia was based on corneal topography and visual acuity testing by two ophthalmologists. With suspicious topographic patterns, another member of the team (HH), who was masked to the comments of the other two physicians, independently studied the map and determined its type using the Randleman system.[5] All Randleman parameters (corneal topographic pattern, RSB, age, CCT and MRSE before surgery), in addition to gender, interval between surgery and ectasia diagnosis in the case group, and interval between surgery and the latest examination in the control group, were extracted and entered in data sheets. RSB was calculated by subtracting the sum of assumed flap thickness for the given microkeratome and ablation depth from the measured preoperative corneal thickness. Actual flap thickness was not measured during or after surgery. Datasets were then categorized according to the Randleman scoring system.[5]

In the first analysis, we studied predictive values, sensitivity and specificity of the Randleman scoring system in our cohort. Multiple logistic regression analysis was conducted to determine factors affecting the disease, and then model fitness was evaluated. A modified scoring system was designed using identified determinants and applied to predict the risk of post-LASIK ectasia via receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and the optimal score cut-off point. Next, sensitivity and specificity of the modified system were determined.

RESULTS

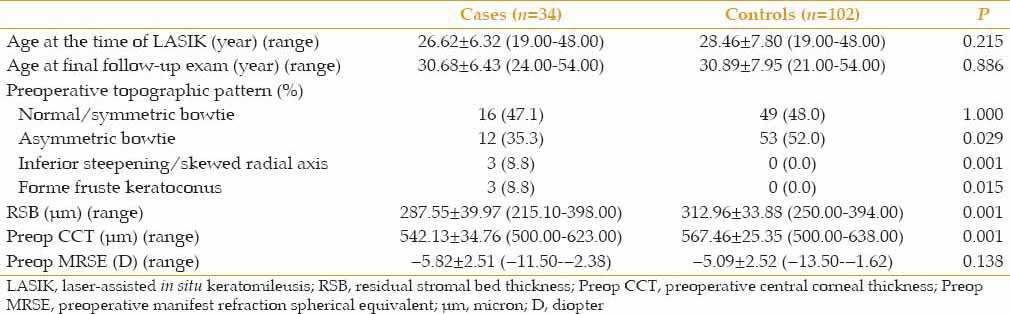

A total of 136 LASIK-treated eyes of 136 patients, including 34 eyes with post-LASIK ectasia and 102 uncomplicated eyes were evaluated. The cohort included 71 (52.2%) female subjects. Mean age of participants at the operation time were 26.62±6.32 and 28.46±7.80 years in ectasia and control groups, respectively. Duration of follow up was 12–98 and 16–98 months in the control and ectasia groups, respectively. According to the Randleman scoring system and based on preoperative data, in the control group 50.5% and 11.9% of eyes were at low and moderate risk, respectively while 37.6% were predicted to be at high risk of developing post-LASIK ectasia. Corresponding figures for the case group were 9.7%, 19.4% and 71.0%, respectively. Accordingly, sensitivity and specificity of the Randleman scoring system were 70.1% and 50.5%, respectively. Demographics and system parameters in the case and control groups are compared in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic data and Randleman corneal ectasia risk score system parameters in the ectasia and control groups

Since the sensitivity and specificity of the Randleman ectasia risk model was relatively low for our subjects, we tried to modify it by incorporating additional parameters. These additional parameters consist of age at the time of LASIK (year), gender (male, female), maximum keratometry reading (max-K) (D), minimum keratometry reading (min-K) (D), and time elapsed since LASIK (months) which were entered as independent variables. Ectasia was entered as an outcome variable. Abnormal topographic patterns included asymmetric bowtie, inferior steepening/skewed radial axis and forme fruste keratoconus.[11]

Multiple logistic regression models showed that the main parameters predictive of post-LASIK ectasia were CCT, MRSE, max-K and time elapsed since LASIK. The regression equation derived was as follows:

Odds ratio of ectasia=0.95 CCT+0.78 MRSE+1.05 months elapsed since LASIK+1.46 max-K In other words, for each micron of increased corneal thickness, the odds of developing corneal ectasia decreased 0.95 times. For each diopter decrease in MRSE or increase in myopia severity, the odds of developing ectasia increased 1.28 times (1/0.78) and for each month passed since LASIK, the odds increased 1.05 times. Finally, each diopter rise in max-K increased the chance of corneal ectasia by 1.5 times. In this model, max-K had the strongest association with corneal ectasia, while CCT and the number of months elapsed since surgery were almost equal and MRSE had the least impact.

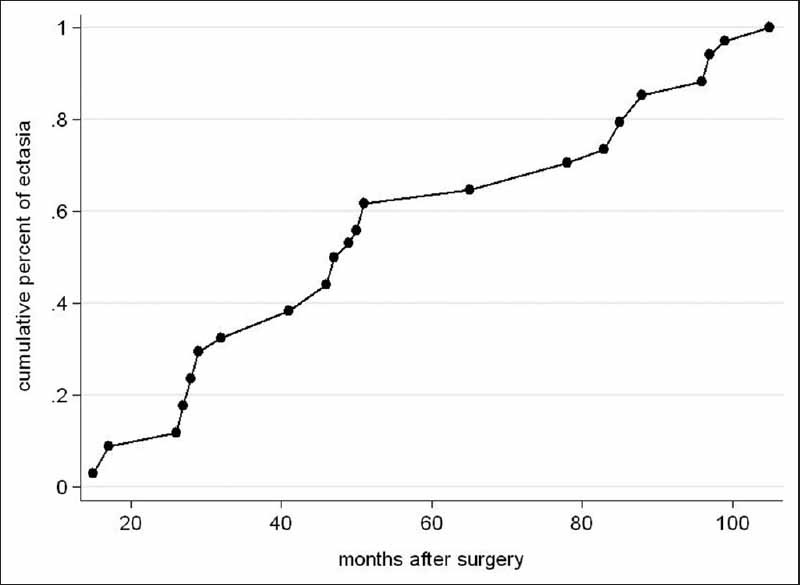

Overall, it can be inferred that a thinner and steeper cornea, higher myopic refraction and longer time elapsed after surgery [Figure 1] are associated with a greater chance of ectasia. Application of the Hosmer–Lemeshow test showed that the fitness of the model was suitable (χ2=8.30, P=0.40).

Figure 1.

The time of onset of corneal ectasia after laser in situ keratomileusis: 25% within 28 months, 50% within 47 months and 75% within 84 months after surgery developed corneal ectasia.

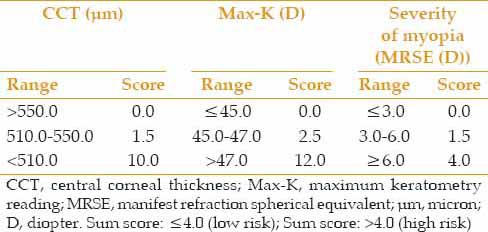

“Time elapsed after LASIK” is a parameter which can only be used in determining the prognosis of the disease and cannot be applied in a screening model, thus the screening system was made based on the variables including CCT, max-K and MRSE. A scoring system was made according to the weight of each parameter [Table 2], and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were drawn (area=0.76, 95% CI=0.66–0.86). A cutoff score of 4.00 provided the best sensitivity and specificity for the revised scoring system. Therefore, subjects whose simple computed score was equal to or <4.00 were considered at low risk of corneal ectasia, and those with scores over 4.00 were considered at high risk. At this point, the sensitivity and specificity of the model were 74.2% and 76.2%, respectively. The difference between the Randleman ectasia scoring system and our modified scoring system was statistically significant in terms of the area under the ROC curve (P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Post-LASIK ectasia risk scoring system

DISCUSSION

The sensitivity and specificity of the Randleman ectasia scoring system in our patient cohort were 70.1% and 50.5%, respectively. In comparison, in Randleman study, corresponding values were reported to be 96.0% and 91.0%.[5] Chan et al[16] found a sensitivity of 56.0% when the Randleman ectasia scoring system was applied to Australian patients. Binder[9] examined the Randleman scoring system in patients who had normal preoperative topography and concluded that it might not accurately predict risk in such patients. In light of the above inconsistencies and controversies around the Randleman scoring system, we revised the scoring system to improve the sensitivity and specificity for patients with normal corneal topography.

In statistical analysis during development of our model, age, RSB thickness and topographic pattern were eliminated. In general, although several studies have shown the effect of preoperative corneal topographic pattern on ectasia,[6,17] in the present study, less risky patterns underwent LASIK. Therefore, this variable was not recognized as an effective factor, and high risk patterns could not be studied. Thus, our model is suitable for patients with normal topographic patterns and the Randleman model is more accurate for those with abnormal ones. In addition, it should be noted that patients with abnormal topographic patterns are not eligible candidates for LASIK today.

Unlike other studies,[3,5,11] we did not find any association between age and ectasia. Since the model aimed to predict the risk of ectasia in LASIK candidates, age at the time of surgery was considered. However, it seems that age at the time of ectasia was considered in other studies, and this difference may offer an explanation for dissimilar results.

RSB thickness in our patients was 288 μm in comparison to 223 μm in Randleman's study. Other studies have reported an RSB of less than 250 μm as a risk factor for ectasia;[6,18] however, this factor remains controversial.[18,19] Due to dependence of RSB on CCT, and the high collinearity of these two variables, the regression model automatically removed RSB. Even if they remain, one of them must be removed manually.[20] A limitation of our study is that actual RSB or flap thickness were not measured directly. RSB was calculated by subtraction of assumed flap thickness and ablation depth from CCT, which can be different from actual RSB. For instance, average flap thickness achieved with a 180 μm plate can be 131±28 μm.[21]

The effect of mean CCT on post LASIK-ectasia has been shown in a number of studies.[7,11,18] where mean preoperative CCT ranged from 445 to 548 μm as compared to 542 μm for mean CCT in the present study. Despite CCT differences in various populations, the role of CCT on ectasia should be emphasized. Our model shows that a CCT less than 510 μm was associated with ectasia more strongly than CCTs of 510–550 μm and significantly increased the odds of ectasia [Table 2]. This finding is in contrast with the Randleman ectasia scoring model in which the relationship between the odds of ectasia and decreasing corneal thickness was almost linear. The fact that surgeons prefer not to perform LASIK in eyes with CCT less than 500 μm confirms these finding.[3,7,22,23]

In the current study, similar to other studies, the occurrence of ectasia increased at higher levels of myopia.[5,22,24] Increasing the depth of ablation in higher myopia correction which thins and weakens the cornea,[25] as well as CCT tending to be reduced with higher levels of myopia makes the cornea more susceptible to ectasia. An important point in the Randleman ectasia scoring system is that the spherical equivalent is used to calculate the effect of refraction on the odds of ectasia, i.e., the cylindrical error is halved. This is in contrast to the fact that the amount of ablation for correcting a diopter of sphere or cylinder is the same. With some LASIK machines, the amount of ablation for correcting astigmatism is even more than that for spherical corrections. Therefore, we propose that the corneal weakening effect of cylinder and sphere correction should be considered the same, and the sum of sphere and cylinder should be entered as an effective parameter. In this study, we applied this change, but since the mean amount of cylindrical error was low in our subjects (−1.2 D), it did not have a significant effect on a predictive model of ectasia. To clarify this hypothesis, future studies should be performed in a population with higher mean astigmatism. In the present study, SE had the least effect on the odds of ectasia as compared with other parameters, albeit mean SE was low (−6D); therefore, it was not possible to study the effect of high myopia on ectasia. Thus, it is recommended to study such effects in a sample with higher mean SE.

Furthermore, preoperative max-K was significantly higher in our cases of ectasia as compared to the control group, and remained in the model as the most effective factor. Since mean keratometry is influenced by min-K and max-K, it seems that max-K is a better indicator for predicting ectasia. In the Tabbara system, mean keratometry was considered as an effective factor predicting ectasia, but this was not recognized in Randleman system.[5] According to our dataset, max-K >47.0 D significantly increased the odds of ectasia as compared to max-K of 45.0–47.0 D and has a stronger effect.

Another point of concern is that as time passes after surgery, the odds of developing corneal ectasia rises. Since post-LASIK corneal ectasia has a cumulative incidence, such a relationship is logical and expected. Clinicians should consider this variable in addition to other risk factors while selecting patients for surgery.

In summary, the Randleman ectasia risk score system exhibited limited ability in predicting this complication in patients with normal corneal topography. Herein, designing a modified screening corneal scoring system, effective factors capable of predicting post-LASIK ectasia in our patients included CCT, MRSE, number of months elapsed after surgery, and max-K. The sensitivity and specificity of the system for our patient cohort was 74.2% and 76.2%, respectively. If data for anterior and posterior elevation, intraoperative RSB, and corneal hysteresis were available, it might have been possible to design a system with higher sensitivity and specificity. Ectasia also occurs in eyes without any known risk factors; we therefore hypothesize there are still underlying undetermined factors requiring further studies.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sugar A, Rapuano CJ, Culbertson WW, Huang D, Varley GA, Agapitos PJ, et al. Laser in situ keratomileusis for myopia and astigmatism: Safety and efficacy: A report by the American Academy of Ophthalmology. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:175–187. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(01)00966-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kanellopoulos AJ. Post-LASIK ectasia. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:1230. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.03.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klein SR, Epstein RJ, Randleman JB, Stulting RD. Corneal ectasia after laser in situ keratomileusis in patients without apparent preoperative risk factors. Cornea. 2006;25:388–403. doi: 10.1097/01.ico.0000222479.68242.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rad AS, Jabbarvand M, Saifi N. Progressive keratectasia after laser in situ keratomileusis. J Refract Surg. 2004;20:S718–S722. doi: 10.3928/1081-597X-20040903-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Randleman JB, Woodward M, Lynn MJ, Stulting RD. Risk assessment for ectasia after corneal refractive surgery. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:37–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.03.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seiler T, Koufala K, Richter G. Iatrogenic keratectasia after laser in situ keratomileusis. J Refract Surg. 1998;14:312–317. doi: 10.3928/1081-597X-19980501-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tabbara KF, Kotb AA. Risk factors for corneal ectasia after LASIK. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:1618–1622. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.03.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Winkler von Mohrenfels C, Salgado JP, Khoramnia R. Keratectasia after refractive surgery. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2011;228:704–711. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1245754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Binder PS. Risk factors for ectasia after LASIK. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2008;34:2010–2011. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2008.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guerra FP, Price MO, Price FW., Jr Is central pachymetry asymmetry between eyes an independent risk factor for ectasia after LASIK? J Cataract Refract Surg. 2010;36:2016–2017. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2010.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Randleman JB, Trattler WB, Stulting RD. Validation of the ectasia risk score system for preoperative laser in situ keratomileusis screening. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;145:813–818. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2007.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fotouhi A, Hashemi H, Khabazkhoob M, Mohammad K. The prevalence of refractive errors among schoolchildren in Dezful, Iran. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91:287–292. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.099937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ostadi-Moghaddam H, Fotouhi A, Khabazkhoob M, Heravian J, Yekta AA. Prevalence and risk factors of refractive errors among schoolchildren in Mashhad, 2006-2007. Iran J Ophthalmol. 2008;20:3–9. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hashemi H, Fotouhi A, Mohammad K. The age-and gender-specific prevalences of refractive errors in Tehran:The Tehran eye study. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2004;11:213–225. doi: 10.1080/09286580490514513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Karimian F. Complications of keratorefractive surgical procedures. Bina. 1999;5:47–58. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chan CC, Hodge C, Sutton G. External analysis of the randleman ectasia risk factor score system: A review of 36 cases of post LASIK ectasia. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2010;38:335–340. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2010.02251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lafond G, Bazin R, Lajoie C. Bilateral severe keratoconus after laser in situ keratomileusis in a patient with forme fruste keratoconus. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2001;27:1115–1118. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(00)00805-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Argento C, Cosentino MJ, Tytiun A, Rapetti G, Zarate J. Corneal ectasia after laser in situ keratomileusis. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2001;27:1440–1448. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(01)00799-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jabbur NS, Stark WJ, Green WR. Corneal ectasia after laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:1714–1716. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.11.1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Menard S. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2001. Applied Logistic Regression Analysis 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miranda D, Smith SD, Krueger RR. Comparison of flap thickness reproducibility using microkeratomes with a second motor for advancement. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:1931–1934. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(03)00786-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Randleman JB, Russell B, Ward MA, Thompson KP, Stulting RD. Risk factors and prognosis for corneal ectasia after LASIK. Ophthalmology. 2003;110:267–275. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(02)01727-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Binder PS. Ectasia after laser in situ keratomileusis. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2003;29:2419–2429. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2003.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Condon PI, O’Keefe M, Binder PS. Long-term results of laser in situ keratomileusis for high myopia: Risk for ectasia. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2007;33:583–590. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2006.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mitooka K, Ramirez M, Maguire LJ, Erie JC, Patel SV, McLaren JW, et al. Keratocyte density of central human cornea after laser in situ keratomileusis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2002;133:307–314. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(01)01421-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]