Summary

Background

Neural networks and their function are defined by synapses, which are adhesions specialized for intercellular communication that can be either chemical or electrical. At chemical synapses transmission between neurons is mediated by neurotransmitters, while at electrical synapses direct ionic and metabolic coupling occurs via gap junctions between neurons. The molecular pathways required for electrical synaptogenesis are not well understood and whether they share mechanisms of formation with chemical synapses is not clear.

Results

Here, using a forward genetic screen in zebrafish we find that the autism-associated gene neurobeachin (nbea), which encodes a BEACH-domain containing protein implicated in endomembrane trafficking, is required for both electrical and chemical synapse formation. Additionally, we find that nbea is dispensable for axonal formation and early dendritic outgrowth, but is required to maintain dendritic complexity. These synaptic and morphological defects correlate with deficiencies in behavioral performance. Using chimeric animals in which individually identifiable neurons are either mutant or wildtype we find that Nbea is necessary and sufficient autonomously in the postsynaptic neuron for both synapse formation and dendritic arborization.

Conclusions

Our data identify a surprising link between electrical and chemical synapse formation and show that Nbea acts as a critical regulator in the postsynaptic neuron for the coordination of dendritic morphology with synaptogenesis.

Introduction

Synaptogenesis proceeds through a prolonged process involving pre- and postsynaptic neuronal specification, dendritic and axonal guidance, the local choice of appropriate synaptic partners, and the trafficking and assembly synaptic machinery. These steps in synapse formation are coordinated with the morphological elaboration of neurons, leading to the proposal of the “synaptotrophic hypothesis”, which posits that synaptogenesis supports and coordinates the development of neuronal morphology[1]. Chemical synapses rely on the precise apposition of synaptic vesicles and exocytic machinery presynaptically with the postsynaptic neurotransmitter receptors and scaffolds that stabilize the synapse[2]. Importantly, neural circuits also contain electrical synapses, which are composed of gap junctions created by the coupling of hexamers of Connexins (Cxs) contributed from each side of the synapse[3]. These gap junctions create channels between the neurons allowing for direct ionic and metabolic communication[3]. Electrical synapses are used broadly during development but are also retained in adult sensory, central, and motor circuits[3–5]. While progress has been made in elucidating mechanisms regulating chemical synapse formation, the genes that underlie electrical synaptogenesis, and whether there are mechanistic commonalities in the formation of these two structurally dissimilar synapse types, is not known.

In a forward genetic screen in zebrafish we identified a mutation in neurobeachin (nbea) as causing defects in the formation of electrical synapses. Nbea is a large (>320 kDa), multidomain protein that is highly conserved amongst vertebrates and mutations have been identified in patients with non-syndromic autism spectrum disorder[6–8]. It is expressed throughout the nervous system and localizes to tubulovesicular membranes near the trans side of Golgi and on pleomorphic vesicles in the cell body, dendrites, and axons[9–11]. Nbea belongs to the family of BEACH (Beige and Chediak-Higashi) containing proteins, which have been implicated in cargo trafficking and endomembrane compartmentalization[6]. It contains many protein-protein interaction domains (tryptophan-aspartic (WD40) repeats, armadillo repeats) suggesting that it may function as a scaffold in the endomembrane system[6]. While nbea mutant mice have no overt defects in endomembrane compartmentalization[11], they do have specific defects in synaptogenesis. nbea mutant mice lack movement and die shortly after birth due to asphyxia correlated with a lack of evoked SV release at neuromuscular junctions[9]. In the central nervous system, nbea mutants have defects in the function of the main excitatory and inhibitory synaptic types (glutamatergic and GABAergic synapses, respectively) and these deficits are correlated with morphological defects in the number of synaptic vesicles presynaptically and the size of the postsynaptic density[11–13]. Additionally, nbea mutants have reduced surface availability of glutamatergic and GABAergic receptors at synapses[11]. No role for Nbea in glycinergic synaptogenesis or electrical synapse formation has been described. Furthermore, whether Nbea controls synaptogenesis pre- or postsynaptically, or both, and if it contributes to the elaboration of neuronal morphology, remains controversial[9, 11–13].

Here we show that Nbea is required for electrical and chemical synaptogenesis in vivo using the individually identifiable neurons and synapses of the zebrafish Mauthner escape circuit. We find that nbea mutants have defects in electrical and glycinergic chemical synaptogenesis and that these defects correlate with deficiencies in the behavioral repertoires of mutant animals. These findings reveal an unexpected commonality in the pathways leading to the assembly of electrical and chemical synapses at the level of Nbea. Using chimeric animals in which identified neurons in the circuit were either mutant or wildtype we find that nbea is necessary and sufficient autonomously in postsynaptic neurons for both electrical and chemical synapse formation. We find that nbea is also necessary and sufficient in the postsynaptic neuron for maintaining an elaborate dendritic arbor. Our data supports the synaptotrophic hypothesis and suggests a model in which postsynaptic Nbea acts within the endomembrane system as coordinator of synaptogenesis and dendritic arborization.

Results

disconnect4 mutants have defects in electrical synaptogenesis

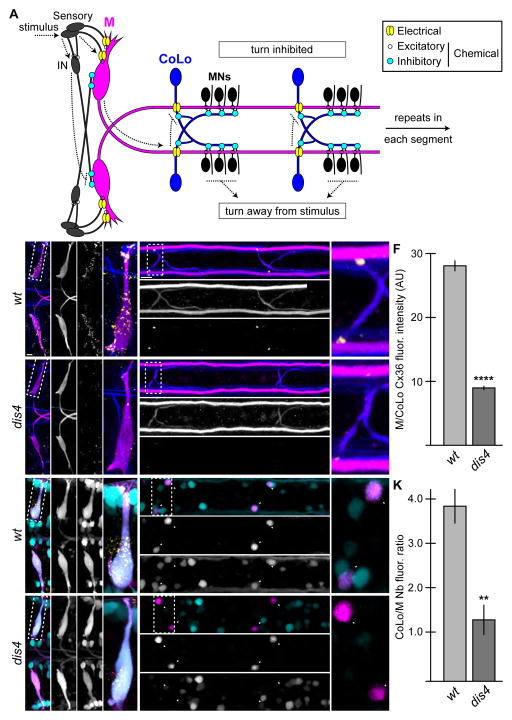

To identify genes required for electrical synaptogenesis we used the Mauthner (M) neural circuit of zebrafish (Fig. 1A). The M circuit is well known for its role in a fast escape response to startling auditory and tactile stimuli, and is wired to allow for very rapid turns away from threats[14]. The circuitry that accomplishes this is relatively simple: sensory neurons relay environmental stimuli via mixed electrical/chemical synapses onto the dendrites of the bilaterally paired M neurons located in the hindbrain. Each M sends a contralateral axon down the length of the spinal cord where it makes segmentally repeated, en passant, excitatory chemical synapses with primary motor neurons (MNs) and separate electrical synapses with inhibitory Commissural Local (CoLo) interneurons. The CoLo interneurons function to suppress turns on the stimulus side by recrossing the spinal cord and inhibiting MNs and CoLo within the same segment. Additionally, sensory neurons in the hindbrain make excitatory chemical synapses with inhibitory interneurons that in turn inhibit the firing of the contralateral M[15–17]. This simple circuitry ensures that turns in response to threatening stimuli occur in a coherent, unidirectional manner.

Figure 1.

Electrical synapses are disrupted in dis4 mutants. A. Model of the Mauthner (M) circuit. Neurons, synapses, and behavioral output are depicted. Hindbrain and two spinal segments are shown. Dotted arrows depict flow of circuit activity given the indicated stimulus. B–J. In this and all subsequent figures, except where noted, images are dorsal views of hindbrain and two spinal cord segments from M/CoLo:GFP larvae at 5 days post fertilization. The ′ figures are zooms of the region denoted by the dotted boxes. Hindbrain and spinal cord images are maximum intensity projections of ~30 and ~10uM, respectively. Anterior is to the left. Scale bar = 10 uM. Larvae are stained for GFP (magenta) and Connexin36 (Cx36, yellow) in all panels, neurofilaments (RMO44, blue) in B–E, and Neurobiotin (Nb, cyan) in G–J. Individual GFP, Cx36, and Nb channels are shown in neighboring panels. Graphs represent data as mean +/− SEM. Statistical significance compared to control is denoted as ** for P<0.01 and **** for P<0.0001. Associated experimental statistics are found in Table S2. B–E. The Cx36 staining found at M dendrites (B,B′) and M/CoLo synapses (C,C′) is reduced in dis4 mutant animals (D,E). F. Quantitation of Cx36 at M/CoLo synapses in wildtype and dis4 mutants. G–J. Electrical synapses are functionally defective in dis4 mutants. Retrograde labeling of M axons with the gap junction permeable dye Nb from a caudal transection. Spinal cord images are at the level of the CoLo cell bodies (arrowheads), which is dorsal to the synapses. G,H. Nb labels the M cell bodies and other caudally projecting neurons (G,G′) and passes through the Cx36 gap junctions to fill the CoLo cell bodies (H,H′, arrowheads). Other neurons are also labeled due to projections caudally into the lesion site. I,J. In dis4 mutants Nb labels M normally (I,I′) however the amount passing into CoLos is diminished (J,J′, arrowheads). K. Quantitation of ratio of Nb in CoLo to M cell bodies in wildtype and dis4 mutants.

We reasoned that mutants affecting electrical synapse formation could be identified relatively easily due to the simple and nearly stereotyped pattern of M/CoLo connections in the spinal cord. M and CoLo can be readily identified using the transgenic line Et(Tol-056:GFP), hereafter called M/CoLo:GFP, which expresses GFP in both types of neurons[18]. Most electrical synapses in the mammalian nervous system are composed of Cx36[3]. The M circuit electrical synapses can be visualized by immunostaining with an antibody against the human Cx36 protein, which detects the zebrafish Cx36-related proteins[19]. The Cx36 staining apparent at the contact site of M and CoLo neurons is exclusively created by these two neurons because laser ablation of either M or CoLo specifically eliminates the synapse (Fig. S1A–E, Table S1).

We screened for mutations by creating gynogenetic diploid animals carrying random mutations generated by the chemical mutagen N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea (ENU)[20] and assessed the effect on electrical synapse formation by staining for Cx36 at 3 days post fertilization (dpf). We identified a mutation, which we called disconnect4 (dis4), that caused a decrease in the amount of Cx36 at both sensory/M and M/CoLo synapses in the hindbrain and spinal cord, respectively (Fig. 1B–E, Table S2). In nbea mutants there were normal numbers of M and CoLo neurons (average number of Ms per animal: wt = 2+/−0, dis4−/− = 2+/−0; CoLos per segment: wt = 1.97+/−0.04, dis4−/− = 1.94+/−0.05; n: wt = 18, dis4 = 7) and their neurites contact each other in the spinal cord as in wildtype (Fig. 1E,E′). Mutants display no gross morphological defects in general body plan development or developmental timing and survive to at least 14 dpf but die before reaching adulthood. While neuronal ablation reduced Cx36 staining at M/CoLo synapses to background levels (Table S1), some Cx36 remained at dis4 mutant synapses, but was reduced by ~3 fold when compared to wildtype siblings (Fig. 1F, Table S2). Mutants showed decreased levels of Cx36 staining in the M circuit from 3–14 dpf and also had decreased Cx36 staining at other prominent electrical synapses in the forebrain, midbrain, hindbrain, and spinal cord suggesting a broad role for the mutated gene in electrical synaptogenesis (Fig. 1 and data not shown).

To investigate whether there was diminished function at the electrical synapses in dis4 mutants we examined the passage of the gap junction permeable dye neurobiotin (Nb) that is known to move from the M axon into CoLo[18]. We retrogradely labeled M axons with Nb from a caudal spinal cord transection and then detected Nb within the CoLo cell bodies in the M/CoLo:GFP line. We found that in mutant animals the amount of Nb transferred across gap junctions from M to CoLo was decreased ~3-fold as compared to the wildtype siblings (Fig. 1G–K, Table S2), similar to the decrease in the amount of Cx36 found at the synapse. Together these data suggest that the gene mutated in dis4 animals is required for electrical synapse formation and function.

neurobeachin is required for electrical synapse formation

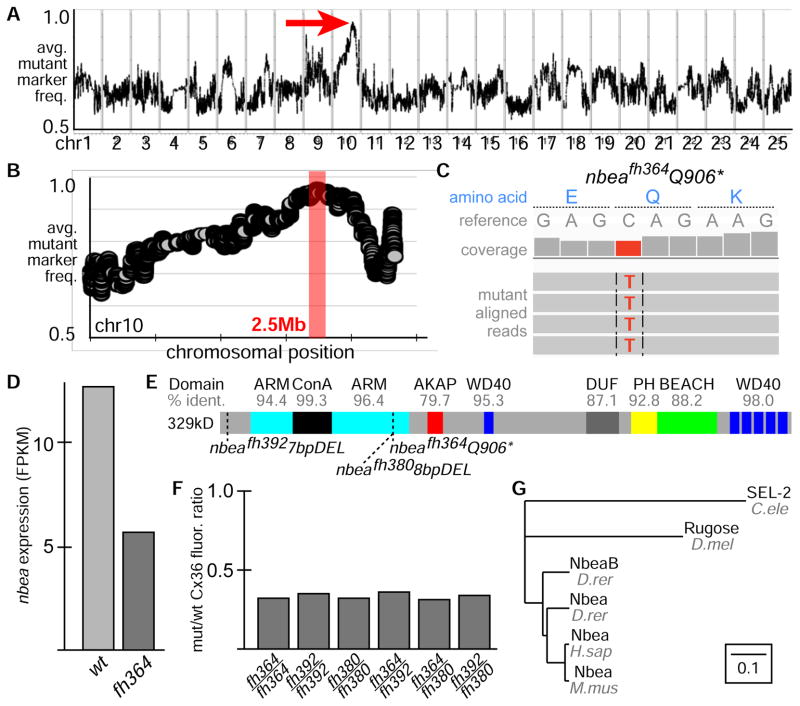

We mapped the dis4 mutation using our recently developed RNA-seq based mapping method[21]. The method is based on a bulk segregant analysis approach where shared regions of genomic homozygosity can be identified in a pool of mutant animals. We pooled 80 mutant (−/−) and 80 wildtype siblings (+/+ and −/+) and extracted and sequenced mRNA (Illumina Hi-Seq) from each pool. Sequence was aligned to the genome and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were identified in the wildtype pool that would serve as mapping markers. The SNP allele frequencies were then examined at the marker positions in the mutant pool identifying a linked region of ~2.5 megabases on chromosome 10 (Fig. 2A,B). Within this region we used the RNA-seq data to identify candidate mutations and found 1 nonsense mutation that truncates the gene neurobeachin (nbea) at amino acid 906, 11 missense changes in other genes, and 2 genes in the interval, including nbea, that had a significantly reduced expression in mutant as compared to wildtype; the decrease in nbea is consistent with nonsense-mediated decay (Fig. 2C,D). To test whether the nonsense mutation in nbea is responsible for the mutant phenotype we generated two frame-shifting deletions in nbea using TALENs[22]: a 7 base pair (bp) deletion in the first exon (nbeafh392) and an 8 bp deletion in exon 21 (nbeafh380) overlapping the location of the ENU-induced dis4 mutation (Fig. 2E). Both nbeafh392 and nbeafh380 failed to complement the dis4 mutation and all mutant allelic combinations resulted in the same ~3-fold reduction in Cx36 staining at M/CoLo synapses (Fig. 2F) suggesting that all alleles are null. For all further analysis we used the dis4 allele, which we renamed nbeafh364.

Figure 2.

The dis4 mutation disrupts neurobeachin. A. Genome wide RNA-seq-based mapping data. The average frequency of mutant markers (black marks) is plotted against genomic position. A single region on chromosome 10 (chr10) emerges with an allele frequency near 1 indicating linkage to the dis4 mutation (red arrow). Each chromosome is separated by vertical lines and labeled at the bottom. B. Detail of chr10, the average frequency of mutant markers (gray discs) is plotted against chromosomal position. A red box marks the region of tightest linkage. Each tick mark on the X-axis represents 10Mb. C. Mutant reads are shown aligned to the reference genome identifying a C to T transition in neurobeachin (nbea) creating a nonsense mutation at amino acid 906. Aligned reads are shown as grey boxes; differences from reference are highlighted by colored letters. D. nbea is downregulated presumably due to nonsense mediated decay (Cufflinks, log2 fold change = −0.82). E. Illustration of the primary structure of Nbea with protein domains depicted as colored boxes, the homology of zebrafish to human domains is labeled (% ident.), and the locations of the mutations are marked by dashed lines. F. Ratio of mutant to wildtype Connexin36 (Cx36) fluorescence at M/CoLo synapses for each allelic combination listed. Wildtype animals were siblings (homozygous and heterozygous) from a given cross. Data for fh364/fh364 is derived from that in Fig. 1F. G. Phylogenetic tree depicting relationships amongst Nbea gene family in common multicellular model organisms. Scale represents substitutions per site.

Nbea is a large, multidomain, scaffolding protein and is highly conserved within vertebrates (Fig. 2E,G)[10]. It is expressed throughout the nervous system in human[23], mouse[9, 10], and zebrafish[24] and localizes to tubulovesicular membranes found near the Golgi, in dendrites and axons, and close to the synapse[10]. We found Nbea protein staining throughout the zebrafish nervous system with a punctate distribution within neuronal cell bodies and extending into the neurites similar to that described in mouse[10, 11]; this staining was lost in mutants further supporting the idea that the nbeafh364 mutation is a null allele (Fig. S2). In zebrafish there are two nbea genes, nbeaa and nbeab – the mutations we have identified/created are in nbeaa (referred to throughout as nbea), which is most closely related to the human and mouse nbea genes (Fig. 2G, percent of identical amino acids compared to human: nbea = 84, nbeab = 81). nbeab is unlikely to have a major role as RNA-seq analysis showed that in wildtype animals nbeab is expressed at a ~10 fold lower level than nbea (nbea = 7.87, nbeab = 0.76, FPKM). We conclude that Nbea is required for electrical synaptogenesis.

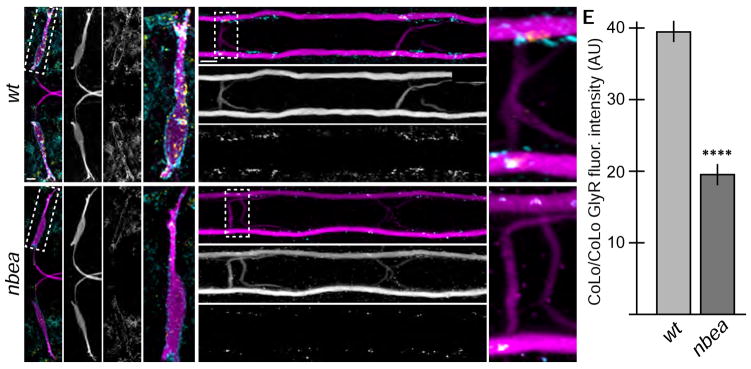

Nbea is required for glycinergic synapse formation

nbea mutant mice have morphologically and functionally defective glutamatergic and GABAergic chemical synapses[11–13], analogous to the defects we see at electrical synapses. While Nbea has been found to biochemically interact with glycine receptors[25], it has not been shown to be required for glycinergic synapse formation. We therefore examined the glycinergic synapses that form onto the M circuit to determine if Nbea was required for their formation. M receives extensive glycinergic input on its dendrite and cell body and expresses glycine receptor (GlyR), which can be detected using immunostaining (Fig. 3)[26]. In the spinal cord we found GlyR staining that localized adjacent to the M/CoLo electrical synapse, and this staining was localized with either the main crossing CoLo axon or with thin processes that branched from CoLo’s main axon. These latter processes are often not visible in images due to their fasciculation with the very large and bright M axon (a visible example is present in Fig. S1G, double arrowhead). The GlyR staining that is near the M/CoLo electrical synapse likely represents CoLo/CoLo inhibitory synapses[15, 18]. Ablating M led to a loss of GlyR staining associated with M dendrites in the hindbrain but had no effect on the staining associated with the presumed CoLo/CoLo sites of contact in the spinal cord (Fig. S1F,G,J). If the two CoLos in the same segment are indeed forming synapses with one another then each CoLo is both postsynaptic on its ipsilateral side of the spinal cord and presynaptic on its contralateral side (see diagram in Fig. 1A). We found that ablating CoLo caused the GlyR punctae on the ablation side (i.e. postsynaptic, arrow, Fig. S1I) to be reduced to background levels (Fig. S1J, Table S1). On the side opposite the ablation (i.e. presynaptic, arrowhead, Fig. S1I) there is an ~35% decrease in the intensity of the GlyR staining (Fig. S1J, Table S1). We conclude that GlyR punctae found adjacent to the M/CoLo electrical synapse are associated with CoLo/CoLo inhibitory synapses.

Figure 3.

Glycinergic synapses are disrupted in nbea mutants. Larvae are stained for GFP (magenta), Connexin36 (Cx36, yellow), and glycine receptor (GlyR, cyan). Individual GFP and GlyR channels are shown in neighboring panels. Graphs represent data as mean +/− SEM. Statistical significance compared to control is denoted as **** for P<0.0001. Associated experimental statistics are found in Table S2. A–D. The GlyR staining found on M dendrites (A) and CoLo/CoLo synapses (B) is diminished in nbea mutant animals (C,D). E. Quantitation of the amount of GlyR in wildtype and mutant CoLo/CoLo synapses. See Fig. 1A for circuit diagram.

Having established that the GlyR staining observed can be attributed to particular neurons of the M circuit we examined the effects of removing Nbea on glycinergic synapse formation. In mutants, GlyR staining was diminished at both Mauthner hindbrain and CoLo/CoLo synapses (Fig. 3A–D). At nbea mutant CoLo/CoLo synapses the amount of GlyR localized at the synapse was decreased ~two-fold when compared to wildtype siblings (Fig. 3E). Mutants showed reduced GlyR staining from 3–14 dpf and GlyR staining, which is found predominantly in the hindbrain and spinal cord, was reduced across all regions in nbea mutants (Fig. 3 and data not shown). The M neuron also receives glutamatergic and GABAergic input; we attempted to visualize these synaptic types by staining for their receptors but could not find suitable antibodies to recognize them. By contrast, when we visualize presynaptic markers (Synapsin, SV2) at central synapses or neuromuscular junctions we find no defects in nbea mutants (Fig. S3). Mice that are heterozygous for a nbea mutation have defects in the size and function of synapses[13]. We find no defects in heterozygous fish (+/fh364) at glycinergic or electrical synapses (Table S2). We conclude that nbea is required for glycinergic synapse formation.

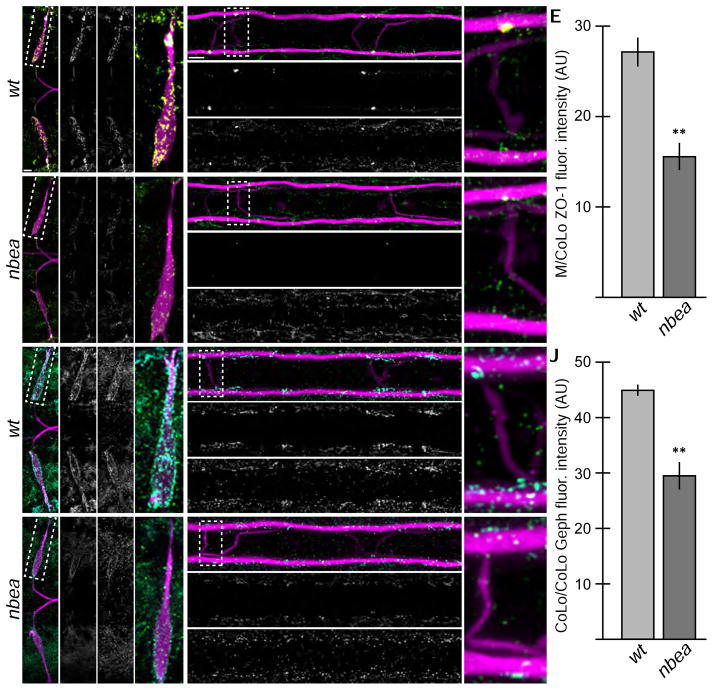

Nbea is required for synaptic scaffold localization

Previous reports suggested that synaptic scaffolds were unaffected in nbea mutant mice[11], however Nbea has been suggested to interact with the glutamatergic scaffold SAP102 directly[27]. We first examined the localization of the electrical synapse scaffold ZO-1, which is known to interact through its PDZ domain with the C-terminus of Cx36[28]. We found that ZO-1 was colocalized with Cx36 within the M circuit as well as at other prominent electrical synapses (Fig. 4A,B). Additional ZO-1 staining was found at non-synaptic tight junctions (Fig. 4 and not shown). In nbea mutants ZO-1 was reduced at all electrical synapses (Fig. 4C–D) but this reduction was less pronounced than the reduction of Cx36 (Fig. 4E, compare to Fig. 1F, Table S2). We next examined the glycinergic scaffold Gephyrin (Geph), which is the main scaffold found at GABAergic and glycinergic inhibitory synapses[29]. In wildtype there was extensive colocalization of GlyR and Geph within the M-circuit as well as more broadly across the hindbrain and spinal cord (Fig. 4F,G and not shown). In nbea mutants Geph was reduced at all synapses (Fig. 4H,I), however, similar to the electrical synapse, the reduction of the scaffold was less pronounced than GlyR (Fig. 4J, compare to Fig. 3E, Table S2). We conclude that the trans-membrane proteins Cx36 and GlyR of the synapse are more dependent on Nbea function than the cytosolic scaffolds.

Figure 4.

Electrical and chemical synaptic scaffolds are disrupted in nbea mutants. Larvae are stained for GFP (magenta) in all panels, Connexin36 (Cx36, yellow) and ZO-1 (green) in A–D, and Glycine receptor (GlyR, cyan) and Gephyrin (Geph, green) in F–I. Individual Cx36, ZO-1, GlyR, and Geph channels are shown in neighboring panels. Graphs represent data as mean +/− SEM. Statistical significance compared to control is denoted as ** for P<0.01. Associated experimental statistics are found in Table S2. Note that for each of spinal cord zoom there is only one M/CoLo and CoLo/CoLo synapse depicted – this is due to natural variation in the positions of CoLo neurons in the spinal cord. A–D. The electrical synapse scaffold ZO-1 is colocalized with Cx36 at M dendritic (A,A′) and spinal cord (B,B′) synapses. ZO-1 staining is diminished in mutants (C,D), but less severely than Cx36. E. Quantitation of ZO-1 at M/CoLo synapses in wildtype and nbea mutants. F–I. The inhibitory synapse scaffold Geph is colocalized with GlyR at M dendritic (F,F′) and CoLo spinal cord (G,G′) synapses. Geph staining is diminished in mutants (H,I), but less severely than GlyR. J. Quantitation of Geph at CoLo/CoLo synapses in wildtype and nbea mutants.

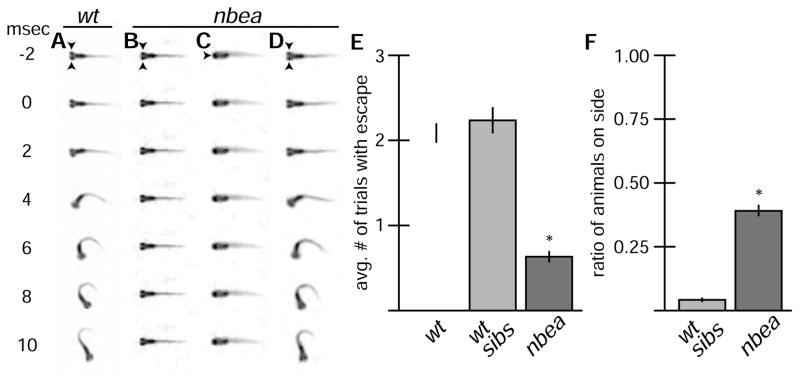

Nbea mutant animals have reduced behavioral performance

We next asked whether the synaptic defects observed in nbea mutants resulted in impaired functionality of the nervous system. The M circuit is one of the first neural circuits to wire and respond in young zebrafish and drives a fast escape response to startling vibrational stimuli at 6 dpf[16]. The M neuron has “segmental homologues” in more posterior hindbrain segments that also contribute to the escape response[30]. M is required for short latency escapes (~10 msec) while the homologues drive similar but longer latency responses (~18 msec)[31, 32]. We created a behavioral testing apparatus consisting of an open arena in which free-swimming animals were confronted with vibrations created from a nearby speaker[18]. Using high-speed videography we found that wildtype animals at 6dpf responded to a 500 Hz, 10 msec tone with escape responses (Fig. 5A). Animals showed no directional bias escaping either to the left or right with both short- and long-latency escapes[18]. We found that nbea mutant animals responded with escapes less than half as frequently as their wildtype (+/+ and +/−) siblings or as compared to a wildtype stock from our facility (Fig. 5B–E, Table S3). Each animal was tested for its response to the tone in three separate trials. While nbea mutant responded in fewer trials than their wildtype counterparts, mutants could perform escape responses that were indistinguishable from wildtype (Fig. 5A,D). The behavioral defects observed were not confined to the escape response as nbea mutant animals were frequently found lying on their sides (Fig. 5C,F). The balance defect was not due to a lack of swim bladders, which in mutants formed at 5 dpf similar to their wildtype siblings, and did not explain the decreased escape response as animals on their side could respond to the tone. By 6 dpf wildtype animals actively correct their balance using their pectoral fins whereas nbea mutants often failed to correct their balance when they began to fall. Additionally we found that animals were less sensitive to touch, displayed decreased overall motion, and were generally less reactive than their wildtype counterparts (Movie S1,S2). However, in all types of behavior, when mutant animals responded they did so with what appeared to be normal coordination, analogous to what we observed in the escape response. We conclude that the loss of nbea leads to broad behavioral deficits that do not prevent normal behavior but decrease its normal occurrence.

Figure 5.

nbea mutants have defects in eliciting normal behavior. A–D. Individual frames from a 500-frame/second movie. Arrowheads point to eyes. Auditory startle stimulus was applied at time = 0. msec = millisecond. Graphs represent data as mean +/− SEM from three separate trials. Statistical significance compared to control is denoted as * for P<0.05 and ns for not significant. Associated experimental statistics are found in Table S3. A. M is responsible for a fast-escape response to threatening stimuli and initiates a turn away from stimulus that is completed in 10 msec. B–D. nbea mutant animals often fail to initiate turns (B), and are frequently found lying on their side (C). However, when they do respond the behavior produced is indistinguishable from wildtype (D). E,F. Quantitation of escape response and balance defects in a separate wildtype line (wt) and nbea mutant animals and their wt siblings (wt sibs). Each animal was tested in three separate trials for its response to stimulus. The average number of trials with response (E) or with animals on their sides (F) was recorded.

Nbea is required autonomously by the postsynaptic neuron for electrical and chemical synapse formation

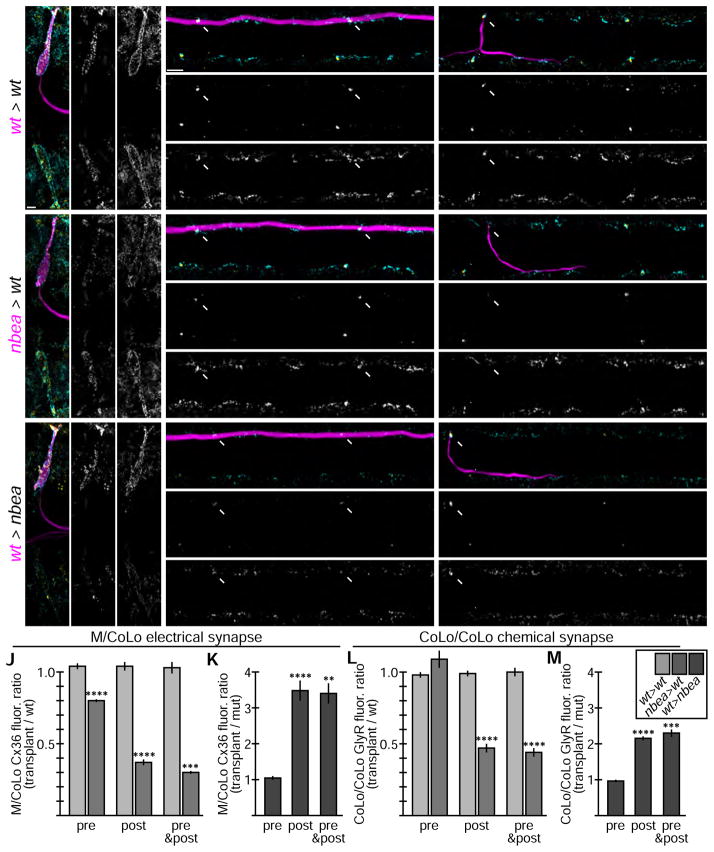

Because Nbea is expressed throughout the nervous system it is unclear whether it functions in the pre- or postsynaptic neuron, or both. Indeed, in mice mutant for nbea there are defects on both sides of the synapse with fewer synaptic vesicles presynaptically and a reduced size of the postsynaptic density[11–13]. To test whether Nbea functions in the pre- or postsynaptic neuron in vivo we wanted to create mosaic animals containing wildtype and mutant cells and examine which required Nbea. We therefore transplanted cells from an M/CoLo:GFP donor into an unmarked host embryo at the blastula stage and examined the resulting embryos at 6 dpf (Fig. 6)[33]. In the transplant experiments chimeric animals were identified with only GFP-marked M, only GFP-marked CoLos, or both; in the case of M we only found examples where a single M was marked with GFP, while the number of GFP-marked CoLos in a chimera ranged from 1 to 13 (average = 3, n = 75, there are ~60 total CoLos per animal). In control transplants there was no effect on Cx36 localization at M/CoLo synapses when comparing synapses associated with GFP-marked and unmarked neurons (Fig. 6A–C,J). To test where nbea was required we transplanted cells from nbea mutant, M/CoLo:GFP donors into wildtype hosts. When the postsynaptic CoLo was nbea mutant the Cx36 staining at the M/CoLo synapse decreased by ~2.5-fold whereas when the presynaptic M axon was mutant there was only an ~20% decrease (Fig. 6E,F,J). When both the pre-and postsynaptic neurons were nbea mutant the decrease in Cx36 was ~3-fold (Fig. 6J, Table S4), similar to the homozygous mutant phenotype (Fig. 1). Analogous to the postsynaptic requirement of Nbea in CoLo, we found that when M is nbea mutant in a wildtype host it loses its synapses in the hindbrain – these synapses are postsynaptic to the incoming sensory input (Fig. 6D). We conclude that Nbea is required mainly postsynaptically for electrical synapse formation.

Figure 6.

Neurobeachin is necessary and sufficient in the postsynaptic neuron for electrical and chemical synapse formation. Dorsal views of chimeric larvae at 6 day post fertilization containing GFP-marked cells transplanted from an M/CoLo:GFP embryo into an unmarked host. Larvae are stained for GFP (magenta), Connexin36 (Cx36, yellow), and glycine receptor (GlyR, cyan). Individual Cx36 and GlyR channels are shown in neighboring panels. The arrows point M/CoLo electrical synapses. The arrows also point to the adjacent postsynaptic side of the CoLo/CoLo synapse associated with the upper left CoLo neuron. The arrowheads point to the presynaptic side of the glycinergic synapse associated with the upper left CoLo neuron. Graphs represent data as mean +/− SEM. Statistical significance compared to control is denoted as ** for P<0.01, *** for P<0.001, **** for P<0.0001, and ns for not significant. Associated experimental statistics are found in Table S4. A–C. Individual examples of control chimeric larvae with cells transplanted from a M/CoLo:GFP embryo into an unmarked wildtype host (wt > wt). D–F. Examples of chimeric larvae testing where Nbea is necessary, with cells transplanted from a nbea mutant M/CoLo:GFP embryo into an unmarked wildtype host (nbea > wt). Note the greatly diminished synapses when the nbea mutant cell is the postsynaptic neuron (D,F). G–I. Examples of chimeric larvae testing where Nbea is sufficient, with cells transplanted from an M/CoLo:GFP embryo into an unmarked nbea mutant host (wt > nbea). Note that synapses are rescued when the postsynaptic neuron is wildtype for Nbea (G,I). J–M. Quantitation of the ratio of Cx36 fluorescence at M/CoLo or GlyR fluorescence at CoLo/CoLo synapses at transplant-associated neurons compared to unassociated neurons within the same animal in wt > wt and nbea > wt chimeras (J,L) and wt > nbea chimeras (K,M).

We next asked if Nbea was sufficient for electrical synapse formation and so created chimeras in which cells from wildtype, M/CoLo:GFP embryos were transplanted into unmarked, nbea mutant hosts. We found that when the postsynaptic CoLo was wildtype in a mutant host the M/CoLo synapse was rescued with a greater-than 3-fold increase in Cx36 fluorescence compared to the mutant synapses within the same animals (Fig. 6I,K). By contrast, when the presynaptic M axon was wildtype in a mutant background there was no rescue of Cx36 (Fig. 6H,K). Similar to the postsynaptic sufficiency of Nbea in CoLo, when M is wildtype in an otherwise nbea mutant animal the Cx36 associated with electrical synapses on its postsynaptic dendrites and cell body in the hindbrain are rescued (Fig. 6G). Moreover, Nbea’s postsynaptic rescue of Cx36 at the synapse is not enhanced when the presynaptic neuron is also wildtype (Fig. 6K). We conclude that Nbea is sufficient postsynaptically for electrical synaptogenesis.

We next asked if Nbea was required postsynaptically for glycinergic chemical synapse formation and so examined the chimeras for GlyR localization. At the CoLo/CoLo synapses removing nbea from the postsynaptic neuron caused a decrease in GlyR fluorescence by ~2 fold whereas removal from the presynaptic neuron had no effect (Fig. 6C,F,L, Table S4); moreover, there was no additive effect when both the pre- and postsynaptic neurons were mutant (Fig. 6L, Table S4). The decrease in GlyR fluorescence when removing nbea from the postsynaptic CoLo is similar to that of the homozygous mutants (Fig. 3). Likewise, when M is nbea mutant in a wildtype animal the GlyR staining on its postsynaptic dendrites in the hindbrain is reduced (Fig. 6D). We found that Nbea was also sufficient in the postsynaptic neuron (be it CoLo or M), but not in the presynaptic neuron, to rescue GlyR localization (Fig. 6G–I, M, Table S4). Taken together we conclude that Nbea is both necessary and sufficient within the postsynaptic neuron for electrical and chemical synapse formation.

Nbea is required autonomously for dendritic complexity

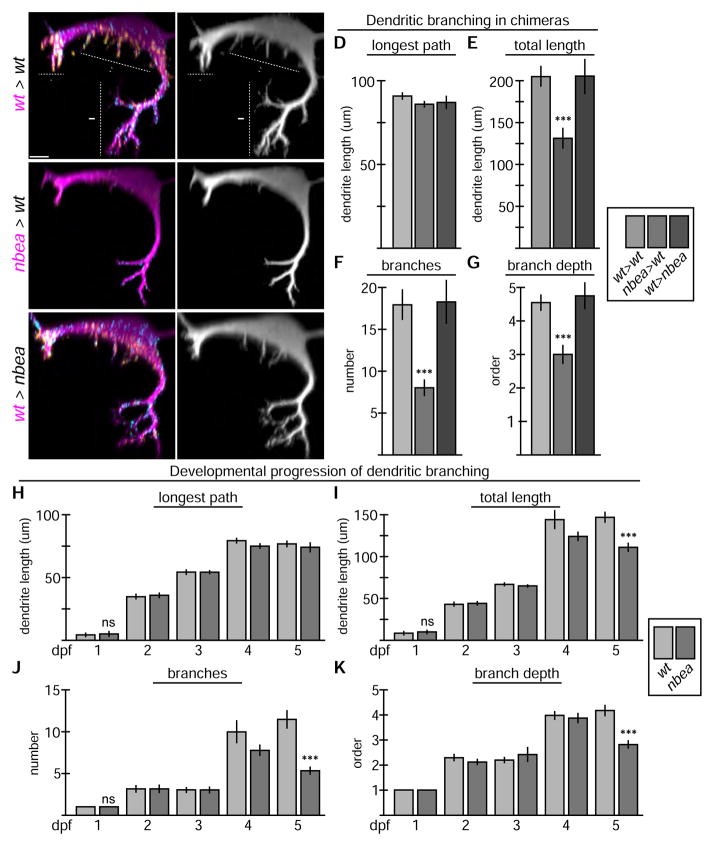

While the major patterns of neural architecture were unaffected in nbea mutants (Figs. 1,3,4) we found that there were defects specifically in the fine terminal branches of M’s dendritic arbor. The M neuron elaborates two main dendritic branches, the lateral dendrite that receives input from sensory neurons and the extensively branched ventral dendrite that receives descending input from higher levels of the brain; M also extends additional fine dendritic processes from the M soma[34]. We found that at 5 dpf nbea mutants have normal axonal development (Fig. 1,3,4) but reduced dendritic complexity (Fig. S4). Analyzing the chimeras we found that nbea is required autonomously by the postsynaptic neuron for dendritic elaboration (Fig. 7A,B). When M is nbea mutant in a wildtype host the length of its main dendritic branch is unaffected (Fig. 7D) but the total arbor length is decreased correlating with fewer branches (Fig. 7E,F, Table S5). In particular the fine terminal dendritic branches are lost with the primary, secondary, and tertiary remaining (Fig. 7G). Furthermore, Nbea was sufficient autonomously in the postsynaptic neuron for the elaboration of fine dendritic arbors since a wildtype M in an otherwise nbea mutant host acquires the dendritic complexity of control transplants (Fig. 7C–G, Table S5). The ventral dendrite data is summarized in Fig. 7D–G, but similar trends are found in the lateral and somatic dendrites as well (Table S5). We conclude that Nbea is required autonomously for dendritic arborization.

Figure 7.

Neurobeachin is required autonomously to maintain dendritic complexity. A–C. Cross section views of individual chimeric larvae containing GFP-marked cells from M/CoLo:GFP embryos in unmarked hosts at 6 days post fertilization. Images are maximum intensity projections of ~20uM from digitally rendered cross sections. For clarity, fluorescent signal outside of the GFP-labeled neurons was digitally removed. Ventral is down, lateral is to the left. Scale bar = 10 uM. Larvae are stained for GFP (magenta), Connexin36 (Cx36, yellow), and glycine receptor (GlyR, cyan). The GFP channel is shown in neighboring panels. Graphs represent data as mean +/− SEM. Statistical significance compared to control is denoted as *** for P<0.001 and ns for not significant. Associated experimental statistics are found in Table S5. A. In wildtype (wt > wt) Mauthner elaborates complex dendrites with three main compartments – ventral (arrow), lateral (arrowhead), and somatic (double arrowhead). B. When M is nbea mutant in an otherwise wildtype host (nbea > wt) the M dendrites lose the fine terminal branches of the dendritic arbor. C. When M is wildtype in a nbea mutant host (wt > nbea) the dendritic complexity is similar to wildtype. D–G. Quantitation of M ventral dendrite parameters in chimeric embryos. H–K. Quantitation of changes in the ventral dendrite from 1 to 5 days post fertilization (dpf) in wildtype and nbea mutant embryos. “Longest path” is the longest continuous main path from cell body to dendrite tip. “Total length” is the sum of the lengths of all the dendritic branches. “Branches” is the sum of the number of branches made off the main, longest branch. “Branch depth” is the maximum depth of branching, with the main branch being primary, and all subsequent branches being labeled sequentially.

We wondered whether the dendritic arborization phenotype was due to defects in the initiation of dendritogenesis or instead in the maintenance of the dendritic arbor. Because the M dendrites are not accessible to live imaging we examined M dendrite formation using fixed stages from 1 to 5 dpf in nbea mutants and wildtype siblings. In wildtype all M dendrites begin outgrowth at approximately 1 dpf, the primary branches growing substantially in the next 3 days and becoming stable between 4 and 5 dpf. However, at this time there is a large increase in the total dendritic arbor size correlated with an increase in the number of branches. In nbea mutants the initial outgrowth and branching of dendrites is unaffected and they are able to generate a complex, branched arbor with fine dendritic branches initially (1–4 dpf, Fig. 7H–K, Fig. S4, Table S5). However, they cannot maintain the fine processes resulting in a loss of complexity (5dpf, Fig. 7H–K, Fig. S4). Taken together these results suggest that Nbea is not required for initiating dendritic complexity, but instead is required to maintain the extensive branching and fine dendritic processes found in mature neurons.

Discussion

Here, using the power of forward genetics in zebrafish coupled with the identified synapses of the M neural circuit in vivo, we found that Nbea is required for electrical synapse formation and function. Little is known about the genes required for electrical synaptogenesis, but the structural differences between electrical and chemical synapses suggest that unique mechanisms would be used for their construction. Thus, Nbea’s involvement in electrical synaptogenesis was surprising given its known role in glutamatergic and GABAergic chemical synapse formation in mouse[9, 11–13]. We also found that Nbea is required for chemical synapse formation in zebrafish, and broaden Nbea’s role yet further by showing that it is required for glycinergic chemical synaptogenesis. Our work, together with the work in mouse, suggests that Nbea is required for the formation of the major forms of synaptic communication within the nervous system. We also find that Nbea is dispensable for axon formation, but is required to maintain the terminal branches of M’s dendritic arbor. Critically, using chimeric analysis in vivo, we find that Nbea is necessary and sufficient in the postsynaptic neuron for electrical and chemical synaptogenesis and dendritic arborization. Our analysis relies mainly on immunofluorescence staining and quantitation of electrical and chemical synaptic components, which has limitations in terms of estimating the phenotypic severity observed. However, we note that our analysis is consistent across experiment types (e.g. homozygous mutants and chimeras). Moreover we show corresponding functional defects at the electrical synapses using neurobiotin passage as our measure. And ultimately, the synaptic defects observed in mutants correlate with deficits in the ability to initiate behavior with normal frequency. Taken together, our findings place Nbea as a broad postsynaptic regulator of synapse formation, with its loss leading to a severely underconnected and underperforming nervous system.

Whether Nbea functions in the pre- or postsynaptic neuron to facilitate synaptogenesis has until now been controversial. Presynaptic function for Nbea is supported by the findings that in nbea mutant mice there is a loss of evoked neurotransmitter release at neuromuscular junctions and central synapses correlated with decreased numbers of SVs and levels of presynaptic proteins[9, 12]. By contrast, postsynaptic function was ascribed due to defects in the size of the postsynaptic density in nbea mutant mice and defects in dendritic spine formation in nbea mutant cultured neurons[11, 13]. Given that Nbea is expressed throughout the nervous system and since feedback between the pre- and postsynaptic neurons is critical for robust synaptogenesis[35], these results have not delineated the primary site of Nbea function. Our results using chimeric analysis in vivo demonstrates unambiguously that Nbea is required in the postsynaptic neuron for both electrical and chemical synapse formation. Consistent with our findings, in two-neuron, co-culture assays, Nbea was required in the postsynaptic neuron for synaptic function[11]. We did find a minor presynaptic requirement for Nbea in electrical, but not chemical, synapse formation leaving open the possibility for presynaptic Nbea function. However, we find that Nbea is sufficient for synaptogenesis only when present postsynaptically in an otherwise mutant animal. That is, even when the presynaptic neuron was mutant, Nbea in the postsynaptic neuron was able to rescue synaptogenesis. Our results suggest that Nbea’s main cell biological role is performed in the dendrites of neurons where it broadly controls electrical and chemical synaptogenesis.

Chemical synapses are inherently asymmetric structures. Synaptic vesicles are poised for release near the active zone presynaptically, while neurotransmitter receptors and associated scaffolds reside postsynaptically[2, 35]. Therefore, it is unsurprising to identify a molecule such as Nbea that is required exclusively postsynaptically for chemical synapse formation. In contrast to chemical synapses, electrical synapses are often viewed as overtly symmetrical structures, being composed of identical hexamers of Cxs contributed by the pre- and postsynaptic neurons[3]. Yet recent results show that electrical synapses can be molecularly asymmetric, with unique pre- and postsynaptic Cxs[19]. Indeed, we have found that different Cx36-related proteins are required pre- and postsynaptically in the zebrafish M circuit for electrical synapse formation (ACM and CBM, unpublished). That Nbea, a putative vesicle trafficking protein, acts postsynaptically suggests that it may function in the dendritic targeting of postsynaptic Cx proteins at molecularly asymmetric electrical synapses. Moreover, Nbea biochemically interacts with synaptic scaffolds[27] and we show that it is required for scaffold accumulation at synapses, suggesting that electrical synapse asymmetry may extend beyond the Cxs, analogous to chemical synapse structure. While Cx regulation can affect electrical synapse function[5], asymmetry of the entire macromolecular complex including the synaptic scaffolds would represent an important new form of control for gap junctional coupling between neurons.

It is widely observed that synapse formation occurs simultaneously with neuronal arborization[1]. Here we find that Nbea is necessary and sufficient in the postsynaptic neuron for both synapse formation and maintaining dendritic complexity. Our findings support a role for Nbea as an important coordinator of synaptogenesis with dendritic arborization, but how this coordination is achieved is unclear. It could be that the loss of neurotransmitter receptors observed in nbea mutants causes the correlated loss of dendritic complexity. For example, in Xenopus tectal neurons blocking NMDA receptor recruitment to nascent synaptic sites causes defects in dendritic arborization[36]. Alternatively, the absence of electrical synapses, themselves inherently adhesive structures[37], might contribute to the destabilization of terminal dendritic branches and their subsequent loss. In line with these possibilities, we found that electrical and chemical synapses were diminished in mutants before we detected changes in dendritic morphology. In contrast to our results, physically ablating sensory input to M early during development resulted in severely reduced dendrites, lacking secondary, tertiary, and terminal branches as well as causing a failure of primary outgrowth in some cases[38]. This suggests that M dendritic arborization occurs in multiple stages with a number of interacting mechanisms and that Nbea’s function occurs after initial contact-mediated support provided by afferent neurons. Together, our results place Nbea as an important coordinator of synapse formation and dendritic complexity yet how it controls these related process remains unknown.

The favored model for Nbea’s function is that it controls the trafficking of synaptic proteins directly. The family of BEACH-containing proteins, to which Nbea belongs, play roles in vesicle trafficking, membrane dynamics, and receptor signaling[6]. Nbea’s localization to vesicular structures found near the trans-face of the Golgi and dendrites suggests a role in trafficking[10]. In support of this idea, recent work showed that when nbea was removed from cultured neurons the surface expression, but not overall level, of glutamate and GABA receptors was reduced with correlated increases in the level of receptors trapped either in the ER and Golgi[11]. In keeping with these results, we found that there were defects in the localization of the trans-membrane receptors (Cxs and GlyR) and the cytosolic scaffolds (ZO-1 and Geph) at electrical and chemical synapses, respectively. If the Nbea vesicle-trafficking model is correct, then Nbea must control either very disparate vesicle types (both electrical and chemical receptor-containing vesicles) or instead a common dendritically targeted vesicle may be involved. However, the nature of the vesicles on which Nbea localizes is uncertain. Costaining of Nbea and endomembrane markers has found that it localizes adjacent to the ER-Golgi complex in the cell body with the best overlap with the SNARE protein Vti1A, whereas in dendrites it is most associated with recycling endosomes[11]. Yet, Nbea punctae are associated with the recycling endosome in only half the cases suggesting a transient interaction with this compartment. Future experiments will be required to identify the mechanistic basis by which Nbea regulates synaptogenesis.

While Nbea’s molecular function is currently unclear, deletions and point mutations in Nbea have been linked to patients with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) [6–8]. Autism is a complex neurodevelopmental disorder controlled by hundreds of genes yet the pathways identified converge on synapse formation and neural circuit function[39]. Our findings suggest that defects in electrical synapse formation and function could be an underlying factor contributing to ASD. While we have focused on electrical synapses that mediate rapid behavioral responses in fish, in the mammalian brain electrical synapses are used broadly and, for example, serve to synchronize ensembles of cortical neurons in the cortex and are important for memory consolidation[3–5]. It is intriguing to consider that the neurological circuit defects that characterize ASD could have a basis in defective electrical synaptogenesis. Indeed, it has been suggested that disruption of Cx36-dependent synchronization within the inferior olive contributes to autism by impairing cognitive processing speed[40]. Thus delineating the biochemical and cell biological role of Nbea in electrical synapse formation may provide critical insight into an underappreciated aspect of this disorder.

Experimental Procedures

Fish, lines, and maintenance

All animals were raised in an Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC)-approved facility at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center. nbeafh364 was isolated from an early-pressure, gynogenetic diploid screen[20] using ENU as a mutagen and were maintained in the M/CoLo:GFP (Et(Tol-056:GFP)) background[18]. nbeafh392 and nbeafh380 were generated using TALENs[22] targeting the 1st or 21st exon of nbea, and stable lines were Sanger sequenced to verify deletions. See Supplemental Experimental Procedures online for more detail.

RNA-seq-based mutant mapping

Embryos in the F3 generation were collected at 3 dpf from known dis4 heterozygous animals, were anesthetized with MESAB (Sigma, A5040), and the posterior portion was removed and fixed for phenotypic analysis via immunohistochemistry (see below) while the anterior portion was placed in Trizol (Life Technologies, 15596-026), homogenized, and frozen to preserve RNA for sequencing. After phenotypic identification mutant (−/−) and wildtype sibling (+/+ and +/−) RNA was pooled separately from 80 embryos each. From each pool total RNA was extracted and cDNA libraries were created using standard Illumina TruSeq protocols. Each library was individually barcoded allowing for identification after multiplexed sequencing on an Illumina HiSeq 2000 machine. There were ~60 million reads per pool and these were aligned to the zebrafish genome (Zv9.63) using TopHat/Bowtie, an intron and splice aware aligner[41]. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were identified using the SAMtools mpileup and bcftools variant caller[42]. Custom R scripts were used to identify high quality “mapping” SNPs in the wildtype pool; these positions were then assessed in the mutant pool for their frequency. The average allele frequency, using a sliding-window of 50-neighboring loci, was plotted across the genome and linkage was identified as the region of highest average frequency. Within the linked region candidate mutations causing nonsense or missense changes, or those affecting gene expression levels, were identified using a combination of custom R scripts and existing software (Variant Effect Predictor[43], Cufflinks[41]). Details can be found at www.RNAmapper.org[21].

Immunohistochemistry

Embryos were fixed and stained using standard procedures, details on antibodies can be found in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Neurobiotin retrograde labeling

Anesthetized 5 dpf embryos were mounted in 1% agar and a caudal transsection through the dorsal half of the embryo was made with an insect pin at somite 20–25. A second insect pin loaded with 5% neurobiotin (Nb) solution was quickly applied to the incision. Animals were unmounted from the agar and allowed to rest for 3 hours while anesthetized to allow neurobiotin to pass from Mauthner into the CoLos. Animals were then fixed in 4% PFA for 2 hours and processed for immunohistochemistry. CoLo axons project posteriorly for a maximum of two segments; therefore measurements of Nb in CoLo were analyzed at least three segments away from the lesion site.

Laser ablation

M, CoLo, or other control GFP labeled neurons were ablated at the earliest time each was detectable using a Micro-Point nitrogen laser. Successful ablation was determined by the immediate loss of all GFP fluorescence within the cell body and stereotypical necrotic appearance of the nucleus and by later absence of the neuron when imaged for experiments.

Cell transplantation

Cell transplantation was done using standard techniques[33] and animals were genotyped as described in mapping above to confirm transplant categories.

Imaging and data analysis

All images were collected on a Zeiss LSM 700 confocal microscope using 405, 488, 555, and 639 laser lines, with each line’s data being collected sequentially using standard pre-programmed filters for the appropriate Alexa dyes. All Z-stacks used 1uM steps. Images were processed and analyzed using Zeiss ZEN and Fiji[44] software. Within each experiment all animals were stained together with the same antibody mix, processed at the same time, and all confocal settings (gain, offset, objective, zoom) were identical. For quantitating fluorescent intensity, synapses were defined as the region of contact between the neurons of interest (M/CoLo for electrical synapse, CoLo/CoLo for the glycinergic synapse). A standard region of interest (ROI) surrounding each synapse was drawn and the mean fluorescent intensity was measured across at least 4uMs in the Z-direction with the highest value being recorded. For neurobiotin backfills fluorescent intensity was measured using a standard ROI encompassing the entire M or CoLo cell body. Dendrite complexity was assessed by first tracing dendrites using the Fiji plugin Simple Neurite Tracer[45]. Dendrite statistics were extracted manually or using the Simple Neurite Tracer’s built in algorithms. Statistics were computed using Prism software (GraphPad). Figure images were created using Photoshop (Adobe) and Illustrator (Adobe). Imaris (BitPlane) was used for the digital cross-sections in Fig. 7 and Fig. S3. In only these images, a mask was created using the GFP channel and any signal outside that mask was removed – this created a clear view of the M neurons, their dendritic complexity, and the closely associated synaptic staining. Colors for all figures were modified using the Fiji plugin Image5D.

Behavioral analysis

Behavioral experiments were performed on 6 dpf larvae and filmed using a high-speed camera (M3, IDT) capturing 500 frames per second. The apparatus for testing startle was adapted from Satou et al.[18]. After behavioral analysis animals were genotyped.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1 – Related to Fig. 1 and 3. Ablation of M circuit neurons reveals connectivity. Images are dorsal views of hindbrain and two spinal cord segments from M/CoLo:GFP larvae at 5 days post fertilization. Hindbrain and spinal cord images are maximum intensity projections of ~30 and ~10uM, respectively. Anterior is to the left. Scale bar = 10 uM. Larvae are stained for GFP (magenta) and Connexin36 (Cx36, yellow) in all panels, neurofilaments (RMO44, blue) in A–D, and Glycine receptor (GlyR, cyan) in F–I. Individual GFP, Cx36, and GlyR channels are shown in neighboring panels. Graphs represent data as mean +/− SEM. Control ablations were GFP+ neurons anterior to M in the hindbrain. Statistical significance compared to control is denoted as ** for P<0.01, **** for P<0.0001, and ns for not significant. Associated experimental statistics are found in Table S1. A,B. M ablation leads to a loss of associated electrical synapses in the hindbrain (A, * marks where the M should have formed) and the spinal cord (B, arrows marks where synapses should have formed). C,D. CoLo ablation has no effect in the hindbrain (C) but leads to a loss of the associated synapse in the spinal cord (D, arrow depicts where synapse should have formed – CoLo in upper left of image was ablated). E. Quantitation of the ratio of Cx36 fluorescence at M/CoLo synapses associated with ablated compared to unablated neurons within an animal. F–I. Each CoLo is both postsynaptic (ipsilateral to cell body) and presynaptic (contralateral to cell body) within the image. The arrows (postsynaptic) and arrowheads (presynaptic) refer to the CoLo located in the upper left of the image. Refer to Fig. 1A for schematic. F,G. M ablation leads to a loss of associated glycinergic synapses in the hindbrain (F, * marks where the M should have formed) but has no effect on GlyR staining in the spinal cord (G). Double arrowhead highlights a thin process extended from CoLo towards the site of the CoLo/CoLo glycinergic synapse – these processes are often not visible given the nearby bright M axon. H,I. CoLo ablation (CoLo in upper left of image was ablated) has no effect on the hindbrain (H) but causes a loss of associated ipsilateral, postsynaptic GlyR staining (I, arrow) and a slight diminishment of the contralateral, presynaptic GlyR (I, arrowhead). J. Quantitation of the ratio of GlyR fluorescence at CoLo/CoLo synapses associated with ablated compared to unablated neurons within an animal.

Figure S2 – Related to Fig. 2. Punctate cytoplasmic Neurobeachin staining is lost in nbea mutants. A,B. Cross section views of M from M/CoLo:GFP transgenic embryos at 5 days post fertilization. Larvae are stained for GFP (magenta), Neurobeachin (Nbea, yellow), and DAPI (blue). Individual Nbea channels are shown in neighboring panels. A. Wildtype Nbea staining appears punctate throughout the cell body and extends out into dendrites (arrowhead). B. Nbea staining is lost in nbea mutants. Images are maximum intensity projections of ~20uM. Ventral is down, lateral is left. Arrowhead points to lateral dendrite. Scale bar = 10 uM.

Figure S3 – Related to Fig. 3. Synaptic vesicle markers are unperturbed in nbea mutants. A–D. Dorsal views of two spinal cord segments of M/CoLo:GFP transgenic line at 5 day post fertilization. A–B. Larvae are stained for GFP (magenta), Connexin36 (Cx36, yellow), and Synaptophysin (Syn, cyan). Individual Cx36 and Syn channels are shown in neighboring panels. C–D. Larvae are stained for GFP (magenta), Connexin36 (Cx36, yellow), and SV2 (cyan). Individual Cx36 and SV2 channels are shown in neighboring panels. E–F. Lateral views of SV2 staining in three segments at the level of the neuromuscular junctions.

Figure S4 – Related to Fig. 7. Neurobeachin is required to maintain dendritic complexity. Cross section views of individual larvae from M/CoLo:GFP transgenic embryos at noted days post fertilization (dpf). Individual GFP channels are shown. A,C,E. In wildtype (wt) dendritic branching in all compartments gets progressively more complex over time. B,D,F. In nbea mutants dendritic outgrowth and branching initiate normally but fail to maintain complexity at 5dpf. Images are maximum intensity projections of ~20uM from digitally rendered cross sections. For clarity, fluorescent signal outside of the GFP-labeled neurons was digitally removed. Scale bar = 10 uM. Ventral is down.

Table S1 – Related to Fig. 1 and 3. Quantitation of neuronal ablation experiments. For all experiments, animals were mounted such that neurons on the right (R) side were ablated. At least three, but generally eight, synapses associated with the noted condition were sampled per animal (n); e.g. when the R Mauthner (M) was ablated, eight CoLos on the left (L) side and eight on the R side were measured for the fluorescence intensity of Connexin36 (Cx36) or glycine receptor (GlyR) at synapses within each animal. For the M/CoLo electrical synapse experiments, M is labeled “pre”synaptic and CoLo “post”synaptic due to the physiological current flow from M to CoLo[S1]. Note that since the M axon crosses to the contralateral side measurements from the L CoLos are affected. When the R CoLo was ablated, there is no longer a definite location for where the synapse should have formed – therefore a location directly opposite that of the existing L CoLo synapse was measured at the level of the M axon. Note that the value obtained is similar to the “M axon” measurement in the “control location measures” section of the table. The M axon measure was sampled at a location halfway between two unaffected M/CoLo electrical synapses at the level of the M axon; this represents the background level of Cx36 in the M axon. For CoLo/CoLo glycinergic synapse experiments, because the CoLos receive synaptic input from their CoLo partners on the contralateral side of the spinal cord, each is both pre- and postsynaptic. Therefore, ablating a R CoLo causes the loss of the neuron that is “post”synaptic on the R (ipsilateral) side, and also a loss of the “pre”synaptic input onto the L (contralateral) side. See Fig. 1A for a circuit diagram. For the “midline” measurement, a location halfway between existing M/CoLo or CoLo/CoLo synapses was measured at the midline of the animal at the level of the M axon; this represents the non-axon background level of staining. Within each animal synapses associated with “unablated” neurons were measured to serve as the control. Synapses on the right side were measured in M ablations of “other” R hindbrain (hb) experiments, while synapses at least two segments away from ablated CoLos were used in all other experiments. Note the variance in the average Cx36 or GlyR staining between experiments – this is due to each experiment being a separately stained set of embryos, with variable antibody staining. However, the average ablated/unablated ratio, taken within each set of animals in an experiment normalizes each experiment allowing for comparison between groups, with the noted standard error of mean (SEM) for each experiment. Significance (sig.) is tested within each experiment against the “other avg. ablated/unablated” ratio using an unpaired, two-tail t-test with Welch’s correction. Blank entries were not determined. All animals were 5 dpf.

Table S2 – Related to Fig. 1, 3, and 4. Quantitation of wildtype and nbea mutant electrical and chemical synapses. The fluorescence signals for Connexin36 (Cx36) and ZO-1 were measured at the M/CoLo electrical synapses; glycine receptor (GlyR) and Gephyrin (Geph) were measured at CoLo/CoLo glycinergic synapses. At least eight synapses associated with the noted condition were sampled per animal, with the noted number of animals (n) being averaged with standard error of means (SEM). For the Neurobiotin experiments the fluorescence was measured for at least eight CoLo cell bodies, averaged, and divided by the fluorescence of the associated M cell body (CoLo/M ratio); this normalized for the amount of neurobiotin added to each M axon. Significance (sig.) is tested for each row against the wildtype (+/+ or +/+ with heterozygote combinations) within each genotype category using an unpaired, two-tail t-test with Welch’s correction. Blank entries were not determined. All animals were 5 dpf.

Table S3 – Related to Fig. 5. Quantitation of behavioral responses in wildtype and nbea mutants. Three rounds of testing were performed for each animal and the average number of trials with a response (# responses) or the number of animals on their sides (# on side) was recorded for the noted number of animals (n). From these three rounds, the average (avg.) was taken for each group and significance (sig.) was tested against the “wildtype” value using the Mann Whitney test. All animals were 6 dpf.

Table S4 – Related to Fig. 6. Quantitation of electrical and chemical synapses in transplant experiments. For all experiments, at least four synapses associated with the noted genotype (geno.) were sampled per animal; e.g. when the Mauthner (M) was transplanted (Xplant), at least four CoLos associated with the GFP+ axon were measured, while at least four CoLos associated with the GFP- axon were measured as control within each animal (n). For the M/CoLo electrical synapse experiments, M is labeled “pre”synaptic and CoLo “post”synaptic due to the physiological current flow from M to CoLo[S1]. When synapses were associated with cases where both M and CoLo neurons were GFP+ those synapses were labeled as “both”. For CoLo/CoLo glycinergic synapse experiments, because the CoLos receive synaptic input from their CoLo partners on the contralateral side of the spinal cord, each is both pre- and postsynaptic. Therefore, the CoLo “pre”synaptic measures are those associated with the synapses contralateral to the transplanted CoLo cell body, while the CoLo “post”synaptic measures are associated with the ipsilateral synapse. When two, paired CoLos within a segment were both GFP+ the associated measure was labeled as “both”. See Fig. 1A for a circuit diagram. The Xplant/host ratio normalizes the fluorescence measure within an animal to the host background. This ratio is computed for each animal and the average is reported in the table with the associated standard error of the mean (SEM). Significance (sig.) is tested for each ratio against the “+/+” control transplant within a “transplanted cell” category using an unpaired, two-tail t-test with Welch’s correction. All animals were 6 dpf.

Table S5 – Related to Fig. 7. Quantitation of dendrites in transplants and at varying developmental stages. For all experiments, the Mauthner (M) dendrite was traced and quantified for a given genotype (geno.) with the noted number of animals (n). Each M dendritic compartment (ventral, lateral, somatic) was quantified separately and the noted measure was averaged and reported with the associated standard error of the mean (SEM). “Longest path” is the longest continuous main path from cell body to dendrite tip. “Total length” is the sum of the lengths of all the dendritic branches. “Branches” is the sum of the number of branches made off the main branch. “Branch depth” is the maximum depth of branching, with the main branch being primary, and all subsequent branches being labeled sequentially. Significance (sig.) is tested for each measure against the “+/+” donor “+/+” host in the transplants, or the wildtype “+/+ & +/fh364” at each developmental stage using an unpaired, two-tail t-test with Welch’s correction. dpf, days post fertilization. For the transplant experiments all animals were 6 dpf. n.a. not applicable.

Movies S1 and S2 – Related to Fig. 5. nbea mutants have defects in touch-induced escape response. Movies were taken with a high-speed camera at 500-frame/second. Movie 1 is a wildtype sibling and Movie 2 is a mutant from a heterozygous incross (nbeafh364/+ x nbeafh364/+). Animals were genotyped after experiments.

Acknowledgments

We thank Rachel Garcia for superb animal care, Kathryn Helde for many, many hours spent in the fish room helping with the forward genetic screen, the Moens lab for discussion and editing, Lila Solnica-Krezel for ENU-mutagenized male zebrafish, Shin-Ichi Higashijima for the M/CoLo:GFP line, and the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center’s Genomic Resource Center, particularly Jeff Delrow, Andy Marty, Alyssa Dawson, and Ryan Basom, for sequencing library preparation, sequencing, and help in data processing. Funding was provided by the National Institute of Health, R01HD076585 and R21NS076950 to CBM and F32NS074839 and K99NS085035 to ACM.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

A.C.M. and L.H.V. performed experiments, acquired and quantified data, and generated images for publication. A.N.S. created the TALENs directed against nbea and generated the mutant animals. A.C.M. and C.B.M. wrote the manuscript. All authors edited the manuscript. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Vaughn JE, Barber RP, Sims TJ. Dendritic development and preferential growth into synaptogenic fields: a quantitative study of Golgi-impregnated spinal motor neurons. Synapse. 1988;2:69–78. doi: 10.1002/syn.890020110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shen K, Scheiffele P. Genetics and cell biology of building specific synaptic connectivity. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2010;33:473–507. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.051508.135302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bloomfield SA, Völgyi B. The diverse functional roles and regulation of neuronal gap junctions in the retina. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2009;10:495–506. doi: 10.1038/nrn2636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peinado A, Yuste R, Katz LC. Extensive dye coupling between rat neocortical neurons during the period of circuit formation. Neuron. 1993;10:103–114. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90246-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pereda AE. Electrical synapses and theirfunctional interactions with chemicalsynapses. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014;15:250–263. doi: 10.1038/nrn3708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cullinane AR, Schäffer AA, Huizing M. The BEACH Is Hot: A LYST of Emerging Roles for BEACH-Domain Containing Proteins in Human Disease. Traffic. 2013;14:749–766. doi: 10.1111/tra.12069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nuytens K, Gantois I, Stijnen P, Iscru E, Laeremans A, Serneels L, Van Eylen L, Liebhaber SA, Devriendt K, Balschun D, et al. Haploinsufficiency of the autism candidate gene Neurobeachin induces autism-like behaviors and affects cellular and molecular processes of synaptic plasticity in mice. Neurobiology of Disease. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Volders K, Nuytens K, Creemers JWM. The autism candidate gene Neurobeachin encodes a scaffolding protein implicated in membrane trafficking and signaling. 2012 doi: 10.2174/156652411795243432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Su Y, Balice-Gordon RJ, Hess DM, Landsman DS, Minarcik J, Golden J, Hurwitz I, Liebhaber SA, Cooke NE. Neurobeachin is essential for neuromuscular synaptic transmission. J Neurosci. 2004;24:3627–3636. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4644-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wang X, Herberg FW, Laue MM, Wullner C, Hu B, Petrasch-Parwez E, Kilimann MW. Neurobeachin: A protein kinase A-anchoring, beige/Chediak-higashi protein homolog implicated in neuronal membrane traffic. J Neurosci. 2000;20:8551–8565. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-23-08551.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nair R, Lauks J, Jung S, Cooke NE, de Wit H, Brose N, Kilimann MW, Verhage M, Rhee J. Neurobeachin regulates neurotransmitter receptor trafficking to synapses. The Journal of Cell Biology. 2013;200:61–80. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201207113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Medrihan L, Rohlmann A, Fairless R, Andrae J, Doring M, Missler M, Zhang W, Kilimann MW. Neurobeachin, a protein implicated in membrane protein traffic and autism, is required for the formation and functioning of central synapses. The Journal of Physiology. 2009;587:5095–5106. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.178236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Niesmann K, Breuer D, Brockhaus J, Born G, Wolff I, Reissner C, Kilimann MW, Rohlmann A, Missler M. Dendritic spine formation and synaptic function require neurobeachin. Nat Comms. 2011;2:557. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Korn H, Faber DS. The Mauthner Cell Half a Century Later: A Neurobiological Model for Decision-Making? Neuron. 2005;47:13–28. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hale ME, Ritter DA, Fetcho JR. A confocal study of spinal interneurons in living larval zebrafish. J Comp Neurol. 2001;437:1–16. doi: 10.1002/cne.1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu KS, Fetcho JR. Laser Ablations Reveal Functional Relationships of Segmental Hindbrain Neurons in Zebrafish. Neuron. 1999;23:325–335. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80783-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pereda A, O’Brien J, Nagy JI, Smith M, Bukauskas F, Davidson KGV, Kamasawa N, Yasumura T, Rash JE. Short-range functional interaction between connexin35 and neighboring chemical synapses. Cell Commun Adhes. 2003;10:419–423. doi: 10.1080/15419060390263254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Satou C, Kimura Y, Kohashi T, Horikawa K, Takeda H, Oda Y, Higashijima SI. Functional role of a specialized class of spinal commissural inhibitory neurons during fast escapes in zebrafish. J Neurosci. 2009;29:6780–6793. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0801-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rash JE, Curti S, Vanderpool KG, Kamasawa N, Nannapaneni S, Palacios-Prado N, Flores CE, Yasumura T, O’Brien J, Lynn BD, et al. Molecular and Functional Asymmetry at a Vertebrate Electrical Synapse. Neuron. 2013;79:957–969. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.06.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walker C, Walsh GS, Moens C. Making Gynogenetic Diploid Zebrafish by Early Pressure. JoVE. 2009 doi: 10.3791/1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller AC, Obholzer ND, Shah AN, Megason SG, Moens CB. RNA-seq-based mapping and candidate identification of mutations from forward genetic screens. Genome Res. 2013;23:679–686. doi: 10.1101/gr.147322.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sanjana NE, Le Cong, Zhou Y, Cunniff MM, Feng G, Zhang F. A transcription activator-like effector toolbox for genome engineering. Nature Protocols. 2012;7:171–192. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hawrylycz MJ, Lein ES, Guillozet-Bongaarts AL, Shen EH, Ng L, Miller JA, van de Lagemaat LN, Smith KA, Ebbert A, Riley ZL, et al. An anatomically comprehensive atlas of the adult human brain transcriptome. Nature. 2012;489:391–399. doi: 10.1038/nature11405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thisse B, Thisse C. [Accessed August 18, 2014];Fast Release Clones: A High Throughput Expression Analysis. 2004 zfin.org. Available at: http://zfin.org/cgi-bin/webdriver?MIval=aa-pubview2.apg&OID=ZDB-PUB-040907-1.

- 25.del Pino I, Paarmann I, Karas M, Kilimann MW, Betz H. The trafficking proteins Vacuolar Protein Sorting 35 and Neurobeachin interact with the glycine receptor β-subunit. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2011;412:435–440. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.07.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yamanaka I, Miki M, Asakawa K, Kawakami K, Oda Y, Hirata H. Glycinergic transmission and postsynaptic activation of CaMKII are required for glycine receptor clustering in vivo. Genes Cells. 2013;18:211–224. doi: 10.1111/gtc.12032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lauks J, Klemmer P, Farzana F, Karupothula R, Zalm R, Cooke NE, Li KW, Smit AB, Toonen R, Verhage M. Synapse Associated Protein 102 (SAP102) Binds the C-Terminal Part of the Scaffolding Protein Neurobeachin. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e39420. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0039420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Flores CE, Li X, Bennett MVL, Nagy JI, Pereda AE. Interaction between connexin35 and zonula occludens-1 and its potential role in the regulation of electrical synapses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:12545–12550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804793105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tyagarajan SK, Fritschy JM. Gephyrin: a master regulator of neuronal function? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014;15:141–156. doi: 10.1038/nrn3670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’Malley DM, Kao YH, Fetcho JR. Imaging the Functional Organization of Zebrafish Hindbrain Segments during Escape Behaviors. Neuron. 1996;17:1145–1155. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80246-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kohashi T, Oda Y. Initiation of Mauthner- or non-Mauthner-mediated fast escape evoked by different modes of sensory input. J Neurosci. 2008;28:10641–10653. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1435-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Burgess HA, Granato M. Sensorimotor gating in larval zebrafish. J Neurosci. 2007;27:4984–4994. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0615-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kemp HA, Carmany-Rampey A, Moens C. Generating Chimeric Zebrafish Embryos by Transplantation. JoVE. 2009 doi: 10.3791/1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kimmel CB. Development of synapses on the Mauthner neuron. Trends Neurosci. 1982;5:47–50. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Siddiqui TJ, Craig AM. Synaptic organizing complexes. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2011;21:132–143. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sin WC, Haas K, Ruthazer ES, Cline HT. Dendrite growth increased by visual activity requires NMDA receptor and Rho GTPases. Nature. 2002;419:475–480. doi: 10.1038/nature00987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Elias LAB, Wang DD, Kriegstein AR. Gap junction adhesion is necessary for radial migration in the neocortex. Nature. 2007;448:901–907. doi: 10.1038/nature06063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kimmel CB, Powell SL, Kimmel RJ. Specific reduction of development of the Mauthner neuron lateral dendrite after otic capsule ablation in Brachydanio rerio. Dev Biol. 1982;91:468–473. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(82)90053-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krumm N, O’Roak BJ, Shendure J, Eichler EE. A de novo convergence of autism genetics and molecular neuroscience. Trends Neurosci. 2014;37:95–105. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2013.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Welsh JP, Ahn ES, Placantonakis DG. Is autism due to brain desynchronization? Int J Dev Neurosci. 2005;23:253–263. doi: 10.1016/j.ijdevneu.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Roberts A, Goff L, Pertea G, Kim D, Kelley DR, Pimentel H, Salzberg SL, Rinn JL, Pachter L, Trapnell C. Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nature Protocols. 2012;7:562–578. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McLaren W, Pritchard B, Rios D, Chen Y, Flicek P, Cunningham F. Deriving the consequences of genomic variants with the Ensembl API and SNP Effect Predictor. J Gerontol. 2010;26:2069–2070. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schindelin J, Arganda-Carreras I, Frise E, Kaynig V, Longair M, Pietzsch T, Preibisch S, Rueden C, Saalfeld S, Schmid B, et al. Fiji: an open-source platform for biological-image analysis. Nat Methods. 2012;9:676–682. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Longair MHM, Baker DAD, Armstrong JDJ. Simple Neurite Tracer: open source software for reconstruction, visualization and analysis of neuronal processes. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:2453–2454. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials