Abstract

Objective

The objective was to identify trajectories of recovery from serious mental illnesses.

Methods

177 members (92 women, 85 men) of a not-for-profit integrated health plan participated in a 2-year mixed methods study of recovery. Diagnoses included: schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, or affective psychosis. Data sources included: self-reported standardized measures, interviewer-ratings, qualitative interviews, and health plan data. Recovery was conceptualized as a latent construct, factor analyses computed and factor scores saved to calculate trajectories. Cluster analyses were used to identify individuals with similar trajectories.

Results

Four trajectories were identified—two stable (high and low) and two fluctuating (higher and lower). Few demographic or diagnostic factors differentiated clusters at baseline. Discriminant analyses for trajectories found differences in mental health symptoms, physical health, satisfaction with mental heath clinicians, resources and strains, satisfaction with medications, and service use. Those with higher scores on recovery factors had fewer mental heath symptoms, better physical health, greater satisfaction with mental health clinicians, fewer strains/greater resources, less service use, better quality care, and greater medication satisfaction. Consistent predictors of trajectories included: mental health symptoms, physical health, resources and strains, and use of psychiatric medications.

Conclusions

Having access to good quality mental health care—defined as including satisfying relationships with clinicians, responsiveness to needs, satisfaction with psychiatric medications, services at levels that are needed, support that can help manage deficits in resources and strains, and care for medical conditions—may facilitate recovery. Providing such care may alter recovery trajectories.

Introduction

Historically, serious mental illnesses were viewed as chronic, non-curable, deteriorating disorders (1,2). Recent research, however, suggests that significant proportions of individuals with these diagnoses improve greatly or recover completely (3–10). In general, recovery rates tend to be consistent with Warner’s analysis of 85 outcome studies of people with schizophrenia—approximately 20–25% of individuals make a complete recovery (defined as absence of psychotic symptoms and return to pre-illness functioning), while 40–45% achieve social recovery (economic and residential independence and low social disruption)(11). Gitlin et al. (12) found similar outcomes among individuals with bipolar disorder on maintenance pharmacotherapy—27% did not relapse; Angst and Sellaro (1) found slightly lower rates of recovery and remission in their review of studies of bipolar disorder.

Less is known about patterns or predictors of recovery trajectories. Cortese et al. (13) found three longitudinal patterns of the clinical course of psychotic disorders (including schizophrenia and bipolar disorder) over a 12-month period: (1) “positive incline” (2) “stable,” and (3) “fluctuating.” Strauss et al. (14) also found evidence of longitudinal patterns indicating recovery; the most important predictors of greater levels of symptoms and disability being the percentage of time experiencing psychotic symptoms in the first two years, younger age at study entry, and a baseline diagnosis of schizophrenia (in contrast to acute schizophrenia or bipolar disorder). The purpose of this study was to identify trajectories of recovery from serious mental illness, and their predictors.

Methods

Setting

The setting for this study was Kaiser Permanente Northwest (KPNW), a not-for-profit integrated health plan serving about 480,000 members in Oregon and Washington State. KPNW provides outpatient and inpatient medical, mental health, and addiction treatment, and maintains an integrated electronic medical record that contains comprehensive administrative and treatment data for all its members. Clinicians are salaried employees of either the health plan or the Permanente Medical Group.

Study Design

The Study of Transitions and Recovery Strategies (STARS) was a mixed methods, exploratory, longitudinal study of recovery among individuals with schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, or affective psychosis. Participants completed four in-depth interviews (two at baseline; one each at 1-year and 2-years following study enrollment) and three paper-and-pencil questionnaires (one each at baseline, 1-year and 2-years). In-depth interviews covered a wide range of domains, including: mental health history, experiences affecting mental health and recovery, symptoms, and mental health care. We also sought information regarding relationships with family and friends, current life circumstances, and role models that influenced participants’ recovery processes. Questionnaires assessed quality of life, happiness, psychiatric symptoms, recovery, stigmatizing experiences, alcohol/drug use, regular activities, living situation, and socio-demographic characteristics. Questionnaire data were linked to health plan records of diagnoses and service use. The study was approved and monitored by KPNW’s Institutional Review Board and Research Subjects Protection Office. All participants provided informed consent prior to participation.

Participant Identification, Inclusion Criteria, and Recruitment

Individuals with diagnoses of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, or affective psychosis were identified using health plan membership and diagnostic records. Additional inclusion criteria included: a minimum of 12 months of health plan membership prior to study enrollment; age 16 years or older; and not planning to leave the area for 12 months. Exclusion criteria included: individuals with diagnoses of dementia, mental retardation, or organic brain syndromes, and those whose mental health clinician felt they were unable to participate at the time of recruitment.

Health plan records identified a pool of eligible participants (n = 1827). Of these, we attempted to recruit 418 individuals before ending recruitment because we reached our planned sample size. Potential participants were stratified based on diagnosis (mood vs. schizophrenia spectrum diagnoses) and gender, and were selected randomly within groups to achieve roughly equal representations by group gender and diagnostic group. Recruitment letters were signed by the principal investigator and members’ primary mental health clinician (213 clinicians signed letters). Of letters sent to clinicians for review, 15.8% of were screened out as unable to participate; 15 clinicians did not return letters, eliminating 17 individuals from the pool. We mailed letters to potential participants over a 10-month period and telephoned individuals when they did not contact us after receiving the letter. Of the 418 to whom we sent letters, we made contact with 350 individuals, received 127 refusals, found 22 individuals ineligible, and enrolled 184. This represented 46% of those who were eligible, and surpassed our recruitment goal of 170 participants. Of the 184 enrolled, 3 did not complete the baseline interviews and 4 were excluded because study staff determined that diagnoses were in error. Thus, the total number of participants was 177.

Subjects

Study participants were 92 women (52%) and 85 men (48%); average age at baseline was 48.8 (SD = 14.8) years, ranging from 16 to 84 years. Sample distributions for age and sex, within diagnosis, did not differ from the eligible population. Basic demographic information appears in Table 1; additional descriptive information has been published elsewhere (15,16).

Table 1.

Demographics

| N of participants that responded to item |

Percent | |

|---|---|---|

| Race1 | 177 | |

| White | 94% | |

| Black or African American | 6 | |

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 3 | |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 2 | |

| Hispanic ethnicity (overlaps all groups) | 176 | 1 |

| Percent reporting mixed-racial heritage (does not include Hispanic ethnicity) | 177 | 5 |

| Diagnosis | 177 | |

| Schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder | 42% | |

| Bipolar disorder | 48 | |

| Affective psychosis | 10 | |

| Education | 173 | |

| Less than high school graduate | 8% | |

| High school graduate | 19 | |

| Some college or technical school | 39 | |

| College graduate | 34 | |

| Marital status | 173 | |

| Never married | 22% | |

| Widowed | 8 | |

| Divorced | 17 | |

| Separated | 3 | |

| Married | 45 | |

| Living with partner | 9 | |

| Employment status | 173 | |

| Paid employment | 40% | |

| Volunteer/unpaid work | 8 | |

| School | 5 | |

| Treatment/rehabilitation program | 2 | |

| Craft/leisure/hobbies | 15 | |

| No structured activity | 15 | |

| Homemaking | 9 | |

| Other | 7 | |

| Prior year household income | 166 | |

| <$10 | 10% | |

| $10–20 | 20 | |

| $20–30 | 16 | |

| $30–40 | 14 | |

| $40–50 | 10 | |

| $50–60 | 9 | |

| $60–80 | 5 | |

| $80 | 5 | |

| Source of income (all that applied, total > 100%) | 173 | |

| Paid employment | 48% | |

| Disability | 25 | |

| Spouse, partner, family | 28 | |

| Retirement, pension, investments, savings | 26 | |

| General assistance, Medicaid, TANF | 2 | |

| Unemployment, alimony, child support | 2 | |

| Other | 13 | |

Totals exceed 100%; participants were asked to indicate all categories that applied.

Data Sources & Measures

Self-reported standardized measures used in analyses presented here include

The Recovery Assessment Scale (RAS) (17); the Wisconsin Quality of Life Index (W-QLI) (18–20); the National Opinion Research Center’s (NORC) General Social Survey general happiness question (21); a modified version of Link et al.’s (22) stigma measures assessing (a) perceived devaluation/discrimination, (b) rejection experiences, (c) secrecy, and (d) withdrawal—employment; the SF-12 health inventory (23); the Colorado Symptoms Inventory (CSI) (24,25); the Patient Activation Measure—Mental Health (PAM-MH) (26); Drake et al.’s (27) self-report rating scales for assessing alcohol and drug use and consequences; regularity of use and satisfaction with psychiatric medications (from the W-QLI); satisfaction with mental health clinician (clinicians’ interest and attention; competence and skills; amount of information and explanation provided); quality of care (28) (calls returned within 24 hours, able to see someone when desired, treated with respect, adequate time during visits, adequate explanation during visits, help develop own treatment goals, providers sensitive to cultural background, given information on services available, given information about rights as a consumer, given adequate information to handle condition); perceived stress; number of traumatic events experienced as an adult; health practices (exercise frequency, current smoker, self-perceived alcohol or drug problem); medication use (number of psychiatric medication classes, number of medication starts/stops).

Interviewer-rated measures included DSM-IV Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scores (29), and Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (30,31) scales for conceptual disorganization, excitement, motor retardation, blunted affect, tension, mannerisms and posturing, uncooperativeness, emotional withdrawal, motor hyperactivity, and distractibility;

As part of interviews, we asked participants about the history of their mental health problems, including when they first began to “feel different” as a way of assessing age of symptom onset; interview responses were converted to a categorical variable (16–29 years [n=18], 30–44 [n=38], 45–59 [n=69], and 60+ years [n=41]). We also asked about the worst symptoms participants had experienced as an assessment of illness severity, and their best year since being diagnosed with mental health problems. Based on the participant’s descriptions, interviewers completed GAF ratings for these two periods.

Measures derived from health plan data included: continuity of care measures for most frequently seen mental health provider, calculated according to Chien et al.’s methods (32); ICD-9 diagnoses for mental health and substance-related disorders; counts of mental health outpatient visits; and dispenses of psychoactive and associated medications, linked to create episodes of medication use and continuity of use, according to Johnson & McFarland’s methods (33). All data collection occurred between April 2003 and February 2008.

Managing Missing Data

For scales, missing data were handled according to each instrument's instructions; if no instructions were available, we required valid responses for at least 75% of the items to compute scales. We then estimated missing values for outcome variables using the expectation-maximization (EM) algorithm. Given that this method sensitive to the variables included for imputation, as predictors we used only scale scores and Likert-type items with fewer than 20% missing values. Before using the EM algorithm, we regressed these variables on each outcome variable for each time point to ensure that the equations explained an adequate amount of variance. The variance explained in each of the outcome variables ranged from 57% to 71%, a sufficient amount to support replacement.

Analyses

Our data included multiple measures designed to assess different dimensions of recovery, thus, for analytic purposes, we conceptualized recovery as a latent construct, based on 7 measures (Total score on the Recovery Assessment Scale; the SF-12 Social Functioning subscale; the SF-12 Role Emotional subscale; the WQLI Occupational subscale; GAF ratings; and NORC’s happiness question). We then computed factor analyses, using principle axis factoring, saving factor scores for each participant for each wave of interviews. Using the resulting factor scores and the quadratic formula, we calculated the intercept, linear slope and quadratic slope for each participant’s recovery trajectory over time. We then entered the intercept, linear slope, and quadratic slope parameters into a hierarchical cluster analysis, using Ward’s Method, and the squared Euclidean distance measure, followed by K-means cluster analysis, to identify groups of individuals with similar recovery trajectories. To assist in understanding cluster differences at baseline, we computed analyses of variance (ANOVA) between each of the recovery measures and cluster membership. We then used discriminant analyses to explore relationships between cluster membership and blocks of conceptually related variables (evaluated as change scores for the follow-up interviews). Blocks of potentially discriminating variables included: mental health symptoms, physical health status, satisfaction with mental health clinician, resources and strains, health practices, medication use, and medication satisfaction (among those taking medications).

Results

Recovery Factor Analyses

The factor analyses for each wave of interviews produced single factors with eigenvalues greater than 1 and accounting for 44.0%, 42.6%, and 44.5% of the variance at baseline, follow-up 1, and follow-up 2, respectively. All variables had strong factor loadings, ranging from .58 to .81 across time points.

Cluster Analysis of Recovery Trajectories

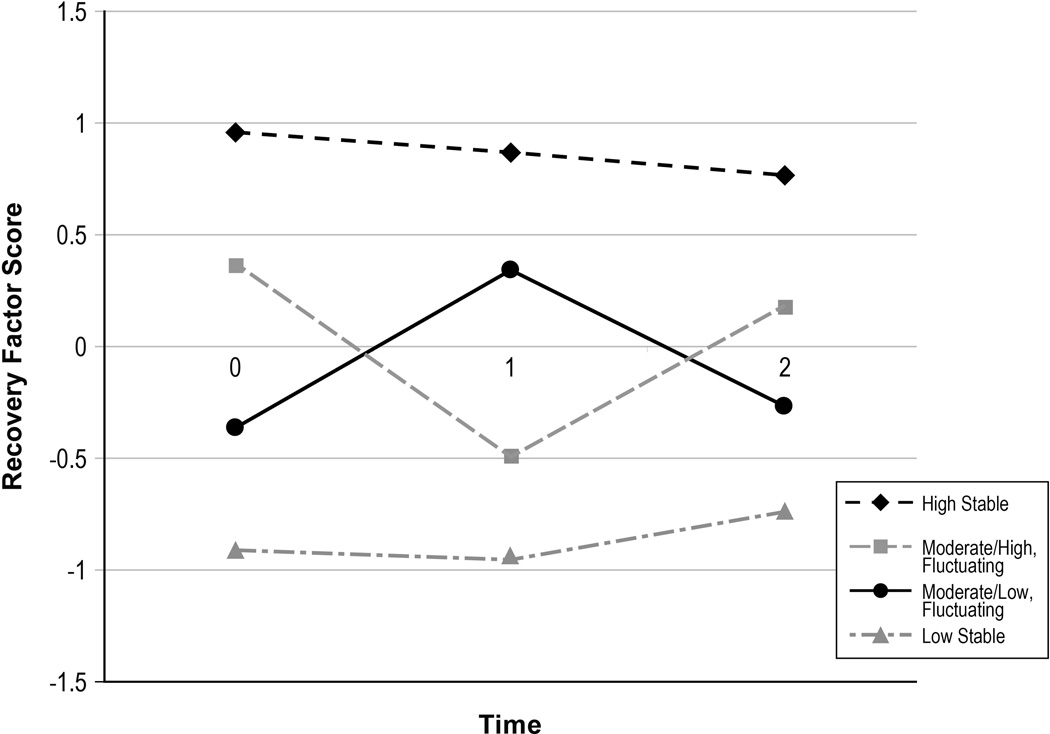

We used each individual’s recovery factor score at each of the 3 time points to compute the cluster analysis (n = 164 [some individuals were lost because critical data were missing]). We selected 4 clusters based on agglomeration schedule, dendrogram, and interpretability. Figure 1 illustrates the mean recovery factor scores at each time point for each cluster. Based on baseline ANOVA results, and the pattern of the trajectory, we named these clusters “High Stable” (n=46), “Moderate/High, Fluctuating” (n=36), “Moderate/Low, Fluctuating” (n=43), and “Low Stable” (n=39).

Figure 1.

Mean Recovery Factor Scores at Baseline, Follow-up 1, and Follow-up 2

Table 2 shows mean baseline values on the recovery measures for the 4 clusters, and presents results of ANOVAs for each. Results are remarkably consistent across clusters, with the High Stable group generally showing the highest levels of recovery and better scores on measures of functioning, followed by the Moderate/High and Moderate/Low Fluctuating groups and the Low Stable group. Table 3 describes the clusters in terms of demographic characteristics and history of mental health problems at baseline. Clusters did not differ on gender, adjusted household income, educational level, disability status, most racial/ethnicity categories, mental health diagnosis, mental health or addiction-related diagnoses, antipsychotic medication use, or history of mental health hospitalization.

Table 2.

Recovery Measures by Cluster at Baseline–ANOVA results.

| High Stable N=46 |

Moderate/High Fluctuating N=36 |

Moderate/Low Fluctuating N=43 |

Low Stable N=39 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | sd | Mean | sd | Mean | sd | Mean | sd | F | df | |

| SF-12 Social Functioning | 49.32 | 8.42 | 44.51 | 14.04 | 35.59 | 11.33 | 35.08 | 11.39 | 16.31 | 3, 160 |

| SF-12 Role Emotional | 48.54 | 9.66 | 40.39 | 11.09 | 34.10 | 9.94 | 31.99 | 11.56 | 21.67 | 3, 160 |

| W-QLI Financial Satisfaction | 1.73 | 1.09 | 1.02 | 1.47 | −0.04 | 1.40 | −0.37 | 1.33 | 22.79 | 3, 160 |

| GAF score | 75.02 | 8.90 | 68.15 | 8.76 | 63.23 | 8.51 | 57.58 | 10.89 | 27.04 | 3, 160 |

| W-QLI General Life Satisfaction | 2.14 | 0.60 | 1.79 | 0.63 | 0.95 | 1.04 | 0.12 | 0.83 | 52.34 | 3, 160 |

| NORC Happiness | 3.46 | 0.58 | 3.25 | 0.55 | 2.72 | 0.63 | 2.34 | 0.66 | 28.37 | 3, 160 |

| Recovery Assessment Scale | 101.80 | 10.77 | 92.48 | 10.82 | 87.78 | 12.14 | 77.92 | 13.81 | 29.31 | 3, 160 |

p < 0.001 for all measures.

The Short Form-12 (SF-12) Social functioning and Role Emotional scales have a possible range from 0 –100 with 100 indicating the highest/best functioning.

The Wisconsin Quality of Life Inventory (W-QLI) preference-weighted Financial Satisfaction subscale (Money subscale) and General Life Satisfaction subscale have possible ranges from −3.00 to 3.00 with 3.00 indicating greater satisfaction.

The Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scale has a possible range from 0 −100 with 100 indicating the best possible functional level.

The Recovery Assessment Scale has a possible range from 24–120 with scores of 120 indicating greater recovery.

Table 3.

Cluster characteristics at baseline.

| High Stable | Moderate/High Fluctuating | Moderate/Low Fluctuating | Low Stable | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Female, % | 46 | 50 | 36 | 56 | 43 | 49 | 39 | 59 |

| Age in years, mean±sd * | 52.02±14.38 | 53.39±13.54 | 45.60±14.16 | 47.13±13.76 | ||||

| Adjusted Household Income, mean±sd | $23,848±$13,446 | $21,476±$15,428 | $19,225±$14,558 | $17,409±$10,136 | ||||

| Education, mean±sd | 4.33±1.10 | 4.28±1.14 | 4.05±1.07 | 3.82±1.19 | ||||

| Working or Student, %* | 46 | 54 | 36 | 36.1 | 43 | 62.8 | 39 | 33.3 |

| Disabled, % | 46 | 4 | 36 | 22.2 | 43 | 14.0 | 39 | 23.1 |

| White, %+ | 46 | 96 | 36 | 92 | 43 | 93 | 39 | 97 |

| African American, % | 46 | 4 | 36 | 8 | 43 | 5 | 39 | 5 |

| Native American/Alaska Native, % | 46 | 4 | 36 | 0 | 43 | 2 | 39 | 5 |

| Asian/Pacific Islander, %* | 46 | 0 | 36 | 0 | 43 | 7 | 39 | 0 |

| Hispanic, % | 45 | 0 | 36 | 0 | 43 | 2 | 39 | 0 |

| Mental Health Diagnosis, % | 46 | 36 | 43 | 39 | ||||

| Schizophrenia | 35 | 42 | 49 | 46 | ||||

| Affective Psychoses | 11 | 8 | 7 | 18 | ||||

| Bipolar Disorder | 54 | 50 | 44 | 36 | ||||

| Mental Health Diagnosis, dichotomized, % | 46 | 36 | 43 | 39 | ||||

| Schizophrenia spectrum | 35 | 42 | 49 | 46 | ||||

| Mood Disorder | 65 | 58 | 51 | 54 | ||||

| Age first “felt different,” %* | 46 | 33 | 41 | 36 | ||||

| Always | 7 | 3 | 5 | 11 | ||||

| Grade school | 11 | 24 | 27 | 39 | ||||

| High school | 24 | 15 | 24 | 17 | ||||

| Age 18 or above | 59 | 58 | 44 | 33 | ||||

| Count of non-inclusion mental health comorbidities, mean±sd | 0.54±1.01 | 0.78±1.07 | 0.67±1.04 | 0.95±1.19 | ||||

| Count of addiction comorbidities, mean±sd | 0.26±0.49 | 0.22±0.42 | 0.26±0.49 | 0.51±0.72 | ||||

| Taking Psychiatric Medications, % | 46 | 91 | 36 | 92 | 43 | 91 | 39 | 92 |

| Lifetime hospitalizations, mean±sd | 2.30±1.28 | 2.69±1.28 | 2.67±1.49 | 3.08±1.77 | ||||

| Worst year GAF, mean±sd* | 41.54±11.28 | 40.47±11.10 | 36.05±10.59 | 36.15±8.81 | ||||

| Baseline GAF minus worst year GAF, mean±sd* | 33.48±12.43 | 27.68±13.09 | 27.19±14.03 | 21.42±13.05 | ||||

| Patient Activation Measure, Mental Health (at follow-up 1), mean±sd* | 67.49±16.06 | 56.83±12.94 | 66.42±13.42 | 55.19±8.54 | ||||

p < 0.05.

participants could code all races that apply so percentages add to > 100%.

The Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) scale has a possible range from 0 −100 with 100 indicating the best possible functional level.

The Patient Activation Measure-Mental Health (PAM-MH) has a possible range from 39–59 with 59 indicating greater activation.

Some differences were apparent, however

Individuals in the Low Stable and Moderate/Low Fluctuating clusters were younger than those in the other two clusters, and the Low Stable and Moderate/High Fluctuating clusters were less likely than the other clusters to be currently employed or students. We found a higher proportion of Asian/Pacific Islanders in the Moderate/Low Fluctuating cluster. The clusters also differed on three indicators of severity of mental health problems. Low Stable and Moderate/Low Fluctuating cluster members reported earlier ages at which they first “felt different” (age of onset indicator) and lower lifetime “worst” GAF scores compared to High Stable and Moderate/High Fluctuating cluster members. Low Stable members recorded the least, and High Stable members the greatest, difference between “worst” GAF score and GAF score at baseline. Finally, the groups differed on levels of patient activation, with the High Stable and Low Stable groups having the highest and lowest levels, respectively.

Discriminant Analyses for Trajectory Clusters

To understand the relationships between key variables and recovery trajectory cluster membership, we explored these relationships using discriminant analyses. Because we had multiple measures of related constructs, variables were tested in blocks. We examined variables collected at baseline, change from baseline to follow-up 1 and change from follow-up 1 to follow-up 2.

The blocks tested at baseline included

Mental health symptoms; physical health; satisfaction with mental health clinician; quality of care; mental health service use; resources and strains (social support, married/cohabiting, satisfaction with finances, perceived stress, patient activation, number of traumatic events experienced as an adult, stigma and discrimination); health practices; medication use (number of psychiatric medication classes and number of starts/stops); and medication satisfaction for those who were taking medications. Means for discriminant functions and associated canonical correlations for significant blocks are presented in Table 4. The canonical correlation is a measure of the degree of relationship between the block of variables and group membership, with higher values reflecting stronger relationships.

Table 4.

Means for discriminant functions and associated canonical correlations at baseline by cluster; changes in means from baseline to the first follow-up; and from first follow-up to second follow-up.

| High Stable | Moderate/High Fluctuating |

Moderate/Low Fluctuating |

Low Stable | Canonical Correlation |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline means | Mental Health Symptoms | −1.26 | −.106 | .551 | .972 | .659 |

| Physical Health | .818 | .278 | −.397 | −.794 | .538 | |

| Satisfaction with MH Clinician | .344 | .193 | .009 | −.608 | .342 | |

| Service Use | −.276 | −.295 | .209 | .367 | .281 | |

| Resources & Strains | 1.13 | .054 | −.257 | −1.12 | .641 | |

| Medication Satisfaction (among medication users) | .594 | .244 | −.112 | −.780 | .460 | |

| Changes from baseline to follow-up 1 in: | Mental Health Symptoms | .193 | .832 | −.993 | −.099 | .550 |

| Physical Health | −.195 | −.340 | . 570 | −.064 | .331 | |

| Resources & Strains | −.341 | −.435 | .339 | .427 | .362 | |

| Changes from follow-up 1 to follow-up 2 in: | Mental Health Symptoms | .024 | −.675 | .689 | −.148 | .436 |

| Medication Use (all) | −.094 | .130 | .324 | −.366 | .258 | |

All canonical correlations were significant at p <.05

In general at baseline, the High Stable cluster had fewer mental health symptoms, better physical health, greater satisfaction with mental health clinicians, more resources and fewer strains, greater medication satisfaction and lower levels of service use. In contrast, the Low Stable cluster was lower on all of these constructs except symptoms and service use, where they were highest. The Moderate/Low Fluctuating cluster had more mental health symptoms and worse physical health at baseline; were moderate on satisfaction with mental health clinician, resources & strains, and medication satisfaction, and higher on service use. The Moderate/High Fluctuating cluster was moderate on mental health symptoms, satisfaction with mental health clinician, resources & strains, and medication satisfaction, higher on physical health, and lower on service use. Level of satisfaction with mental health clinicians, resources and strains, and medication satisfaction (among those taking medications) appeared to differentiate the two clusters that were moderate/low at baseline. The Moderate/Low Fluctuating cluster was associated with higher satisfaction with mental health clinicians, better resources (and lower strains), and greater medication satisfaction than the Low Stable cluster.

For follow-up 1 we used change scores from baseline to follow-up 1 for each set of variables, and tested the same sets of conceptually derived blocks. Cluster membership was significantly associated with changes in mental health symptoms, physical health, and resources & strains.

The High Stable cluster had a slight increase from baseline to follow-up 1 in mental health symptoms and a slight decline in physical health. They also had a reduction in resources and increased strains. The Moderate/High Fluctuating cluster had increased mental health symptoms, worse physical health, and worse resources and strains from baseline to follow-up 1, while the Moderate/Low Fluctuating cluster improved in all three areas. The Low Stable cluster had no change in mental health symptoms or physical health but improved in resources & strains.

In the final set of discriminant analyses, we tested change from follow-up 1 to follow-up 2 using the same set of blocks as in previous analyses. Change in Mental Health Symptoms and Medication Use were the only significant blocks for these analyses. Individuals in the High Stable and Low Stable clusters showed little change in mental health symptoms. In contrast, Mental Health Symptoms decreased among those in the Moderate/High Fluctuating cluster, and increased among those in the Moderate/Low Fluctuating cluster. Individuals in the Moderate/Low Fluctuating cluster also showed increased medication starts and stops at follow-up 2 compared to follow-up 1, while those in the Low Stable cluster had fewer medication starts and stops. The High Stable and Moderate/High Fluctuating clusters showed little change in medication use.

Limitations

Our sample differs from those in public sector settings, so generalizability may be limited: Participants were more likely to be married and employed, and to have higher education and income levels than individuals receiving care in the public sector. It may be that individuals with such characteristics are more likely to have access to a private health plan. An alternative explanation, however, is that good clinical relationships and long-term continuity of care (34) affected these outcomes. Another limitation may result from our decision to have mental health clinicians screen participants for ability to participate at the time of recruitment. It is possible that individuals with lower levels of recovery may have been more likely to be screened out as part of this process.

Discussion

We found evidence for four recovery trajectories—two stable (high and low) and two fluctuating (higher and lower). Analyses of cluster characteristics at baseline suggest that few demographic or diagnostic factors differentiate the clusters. Exceptions included that: (a) older individuals were more likely to be further along in the recovery process, as expected, given opportunities for learning and adapting to chronic illness that occur over time (35,36) and (b) the low stable cluster had the lowest patient activation levels, had experienced the worst lifetime symptom levels compared to the other groups, and were less likely to be working or students.

Discriminant analyses were useful for understanding trajectory cluster membership. At baseline, we found differences in mental health symptoms, physical health, satisfaction with mental heath clinicians, resources and strains, satisfaction with medications, and service use. Generally, those with higher scores on our recovery factors had fewer mental heath symptoms, better physical health, greater satisfaction with their mental health clinicians, fewer strains and greater resources, less service use, and greater medication satisfaction. In addition, there was a trend toward receiving better quality of care among those with higher recovery levels. The most consistent factor predicting recovery trajectory was mental health symptoms and changes in mental health symptoms. Changes in resources and strains, and use of psychiatric medications were also predictive of recovery trajectories, but less consistently.

Conclusions and Implications for Practice

These results suggest that having access to good quality mental health care—defined as including satisfying relationships with clinicians, responsiveness to needs, satisfaction with psychiatric medications, services at levels that are needed, support that can help manage deficits in resources and strains, and quality care for medical conditions—may facilitate recovery. In addition, because these factors are closely related to symptom control and medication use (34), providing such care has the potential to change recovery trajectories over time.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health (Recoveries from Severe Mental Illness, R01 MH062321). The authors would like to thank Michael Leo for analytic support, Elizabeth Shuster and Jeff Showell for help with data extraction, and interviewers Sue Leung, Alison Firemark and Micah Yarborough for their excellent interviews, help developing the qualitative coding scheme, and for coding interviews.

Footnotes

The authors report no competing interests.

References

- 1.Angst J, Sellaro R. Historical perspectives and natural history of bipolar disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2000;48:445–457. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(00)00909-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harding CM, Zahniser JH. Empirical correction of seven myths about schizophrenia with implications for treatment. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1994;(Supplement 384):140–146. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1994.tb05903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davidson L, McGlashan TH. The varied outcomes of schizophrenia. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;42:34–43. doi: 10.1177/070674379704200105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeSisto MJ, Harding CM, McCormick RV, et al. The Maine and Vermont three-decade studies of serious mental illness. I. Matched comparison of cross-sectional outcome. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;167:331–342. doi: 10.1192/bjp.167.3.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DeSisto MJ, Harding CM, McCormick RV, et al. The Maine and Vermont three-decade studies of serious mental illness: II. Longitudinal course comparisons. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;167:338–342. doi: 10.1192/bjp.167.3.338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harding CM, Brooks GW, Ashikaga T, et al. The Vermont longitudinal study of persons with severe mental illness, I: Methodology, study sample, and overall status 32 years later. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1987;144:718–726. doi: 10.1176/ajp.144.6.718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harding CM, Brooks GW, Ashikaga T, et al. The Vermont longitudinal study of persons with severe mental illness, II: Long-term outcome of subjects who retrospectively met DSM-III criteria for schizophrenia. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1987;144:727–735. doi: 10.1176/ajp.144.6.727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harding CM, Zubin J, Strauss JS. Chronicity in schizophrenia: Revisited. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1992;(Supplement 18):27–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harrison G, Hopper K, Craig T, et al. Recovery from psychotic illness: A 15- and 25-year international follow-up study. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;178:506–517. doi: 10.1192/bjp.178.6.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hopper K, Harrison G, Wanderling JA. An overview of course and outcome in ISoS. In: Hopper K, Harrison G, Janca A, et al., editors. Recovery from schizophrenia. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Warner R. Recovery from Schizophrenia. London: Routledge; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gitlin MJ, Swendsen J, Heller TL, et al. Relapse and impairment in bipolar disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1995;152:1635–1640. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.11.1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cortese L, Malla AK, McLean T, et al. Exploring the longitudinal course of psychotic illness: A case-study approach. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;44:881–886. doi: 10.1177/070674379904400903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strauss JS, Hafez H, Lieberman PB, et al. The course of psychiatric disorder, III: Longitudinal principles. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1985;142:289–296. doi: 10.1176/ajp.142.3.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Young AT, Green CA, Estroff SE. New endeavors, risk taking, and personal growth in the recovery process: findings from the STARS study. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59:1430–1436. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.59.12.1430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wisdom JP, Saedi GA, Green CA. Another breed of "service" animals: STARS study findings about pet ownership and recovery from serious mental illness. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2009;79:430–436. doi: 10.1037/a0016812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corrigan PW, Giffort D, Rashid F, et al. Recovery as a psychological construct. Community Mental Health Journal. 1999;35:231–239. doi: 10.1023/a:1018741302682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Becker M. A US experience: Consumer responsive quality of life measurement. Canadian Journal of Community Mental Health. 1998;41:58. doi: 10.7870/cjcmh-1998-0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Becker M, Diamond R, Sainfort F. A new patient focused index for measuring quality of life in persons with severe and persistent mental illness. Quality of Life Research. 1993;2:239–251. doi: 10.1007/BF00434796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Diamond R, Becker M. The Wisconsin Quality of Life Index: A multidimensional model for measuring quality of life. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(Suppl 3):29–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.National Opinion Research Center (NORC) General Social Survey. National Opinion Research Center (NORC) 2012 10-10-2012. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Link BG, Struening EL, Rahav M, et al. On stigma and its consequences: Evidence from a longitudinal study of men with dual diagnoses of mental illness and substance abuse. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1997;38:177–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. SF-12: How to score the SF-12 physical and mental health summary scales. Boston: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boothroyd RA, Chen HJ. The psychometric properties of the Colorado symptom index. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2008;35:370–378. doi: 10.1007/s10488-008-0179-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shern DL, Wilson NZ, Coen AS, et al. Client outcomes II: Longitudinal client data from the Colorado treatment outcome study. Milbank Quarterly. 1994;72:123–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Green CA, Perrin NA, Polen MR, et al. Development of the Patient Activation Measure for mental health. Administration and Policy in Mental Health. 2010;37:327–333. doi: 10.1007/s10488-009-0239-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Drake RE, Osher FC, Noordsy DL, et al. Diagnosis of alcohol use disorders in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1990;16:57–67. doi: 10.1093/schbul/16.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bartlett J, Chalk M, Manderscheid RW, Wattenberg S. Finding common performance measures through consensus and empirical analysis: The forum on performance measures in behavioral healthcare. In: Manderscheid RW, editor. Center for Mental Health Services. Mental Health, United States, 2004. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2006. DDHS Pub No. SMA06-4195[8]. [Google Scholar]

- 29.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition text revision (DSM-IV-TR) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Overall JE, Gorham DR. The brief psychiatric rating scale. Psychological Reports. 1962;10:799–812. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lukoff D, Liberman RP, Nuechterlein KH. Symptom monitoring in the rehabilitation of schizophrenic patients. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1986;12:578–602. doi: 10.1093/schbul/12.4.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chien CF, Steinwachs DM, Lehman A, et al. Provider continuity and outcomes of care for persons with schizophrenia. Mental Health Services Research. 2000;2:201–211. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnson RE, McFarland BH. Lithium use and discontinuation in a health maintenance organization. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1996;153:993–1000. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.8.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Green CA, Polen MR, Janoff SL, et al. Understanding how clinician-patient relationships and relational continuity of care affect recovery from serious mental illness: STARS study results. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2008;32:9–22. doi: 10.2975/32.1.2008.9.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Green CA. Fostering recovery from life-transforming mental health disorders: A synthesis and model. Soc Theory Hlth. 2004:293–314. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.sth.8700036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Charmaz K. Good days, bad days: The self in chronic illness and time. New Brunswick: New Jersey, Rutgers University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]