Dear Editor,

Shwachman-Diamond syndrome (SDS) is an autosomal recessive disorder (OMIM 260400) characterized by exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, skeletal abnormalities, and hematologic dysfunction, with up to 30% risk of developing MDS. The SBDS gene (OMIM 607744) maps to chromosome 7q11.21, and 90% of SDS patients possess mutations of this gene [1].

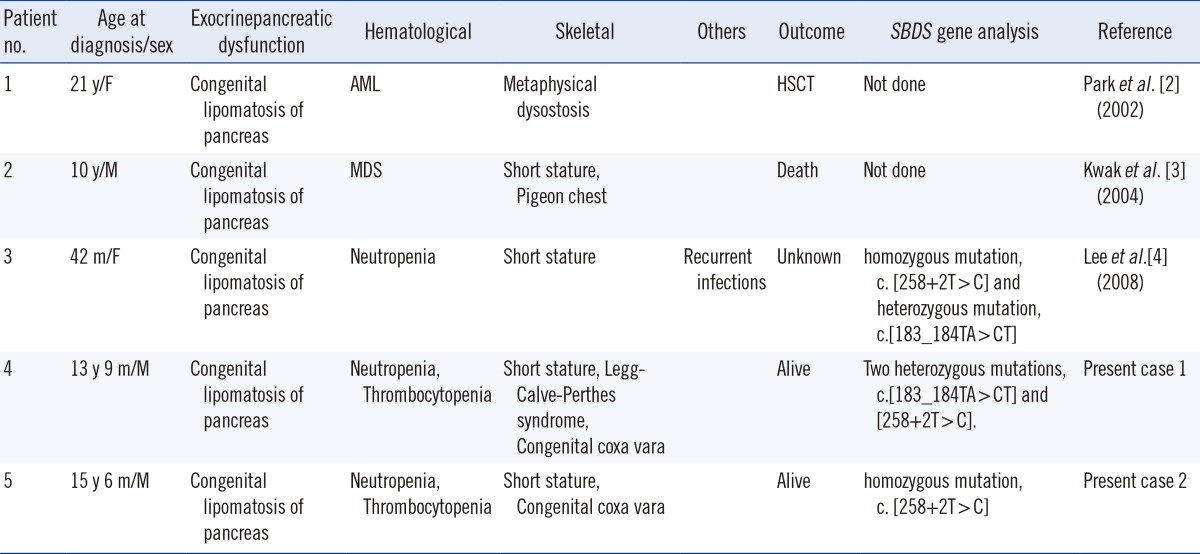

To date, three SDS cases have been reported in Korea, and only one has been confirmed on the basis of SBDS genetic analysis [2, 3, 4] (Table 1). We describe two cases of unrelated Korean adolescent SDS patients. We received approval from the Institutional Review Board of Seoul St. Mary's Hospital.

Table 1.

Clinical features of SDS patients reported in Korea

Abbreviations: SDS, Shwachman-Diamond syndrome; y, yr; m, month; HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

A boy of 13 yr and 9 months underwent a corticotomy of the right femur and external fixation with the Ilizarov method to correct a genu valgum orthopedic deformity. While hospitalized, congenital lipomatosis of the pancreas was unexpectedly observed in an abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan for hisdyspepsia.

There were no abnormal findings in his birth, family, and sibling histories. He was the younger of the two children. A brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for failure to thrive (FTT) at 6 months old, growth hormone stimulation test, chromosomal analysis, and chromosomal breakage test conducted for short stature at 11 yr old and newly observed neutropenia at 13 yr old were normal.

At diagnosis, the weight and height of the patient were each below the 3rd percentile (35 kg and 139 cm). The results of a peripheral blood (PB) examination were as follows: leukocyte count, 3.31×109/L (neutrophils 5%, lymphocytes 88%, monocytes 5%, and eosinophils 0%); hemoglobin, 12.3 g/dL (mean cell volume [MCV] 90.7 fL); platelet count, 109×109/L; Hb F, 1.2%. Low digestive enzyme levels with respect to amylase were found (52 U/L, normal range: 48-176 U/L), lipase was 4.0 U/L (7.0-50.0 U/L) and trypsin was less than 50 ng/mL (110-460 ng/mL).

A boy of 15 yr and 6 months was accidently diagnosed as having congenital lipomatosis of the pancreas by CT scan in the course of a differential diagnosis of appendicitis. There were no abnormal findings in the birth, family, and sibling histories, and he was the youngest child of three boys. He had been followed up for mild cytopenia without transfusion in another hospital since 12 months of age, and valgus osteotomy was done for congenital coxa vara at 7 yr of age.

At diagnosis, the patient was below the 3rd percentile for height and 10th percentile for weight (48 kg and 154.8 cm). The results of a PB examination were as follows: leukocytes, 3.68×109/L (neutrophils 33%, lymphocytes 56%, monocytes 10%, and eosinophils 1%); hemoglobin, 13.6 g/dL (MCV 95 fL); platelet count, 103×109/L; and Hb F, 1.8%. A low level of amylase (30 U/L, normal range: 48-176 U/L) was observed, and lipase (23.8 U/L, 7.0-50.0 U/L) and trypsin (200 ng/mL, 110-460 ng/mL) were within the normal ranges.

Genomic DNA was isolated from PB leukocytes by using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hamburg, Germany). PCR was carried out by using gene-specific primers for exon2 of SBDS [5]. Since an unprocessed pseudogene, SBDSP, resides in a locally duplicated genomic segment of 305 kb [6], the specificities of the primers were checked by using Primer-BLAST (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.proxy.cuk.ac.kr:8080/tools/primer-blast) and also in 10 normal controls.

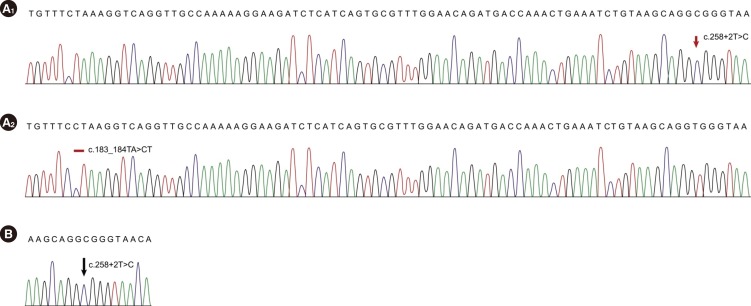

All mutations were described according to the Human Genome Variation Society nomenclature [7]. RefSeq ID: NM_ 016038.2 was used for the alignment. Direct sequencing of the PCR products revealed two heterozygous mutations, c.183_ 184TA>CT and c.258+2T>C, for Case 1 and a homozygous mutation c.[258+2T>C];[258+2T>C] for Case 2 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

The chromatograms of SBDS mutations in the present SDS cases. (A) Case 1: Sequencing chromatograms of subcloned PCR products demonstrate the compound heterozygosity of c.258+2T>C (A1) and c.183_184TA>CT (A2) mutations. (B) Case 2: Direct sequencing shows a homozygous mutation, c.258+2T>C, in intron 2.

We subcloned the PCR products with a TOPO TA Cloning Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and sequenced the products to confirm the zygosity of the mutations in Case 1. Direct sequencing of the cloned PCR products demonstrated that the two heterozygous mutations were compound heterozygous, c.[183_ 184TA>CT];[258+2T>C].

SDS is the second most common cause of inherited exocrine pancreatic dysfunction in children. A short stature seemed to be caused by intrinsic factors of SDS and risk factors such as malabsorption, delayed puberty, and infections [8].

The most frequently reported mutation type, c.[183_ 184TA>CT], forms in-frame stop codons, while c.[258+2T>C] forms truncated proteins by the destruction of donor splice sites [6]. Based on the guidelines proposed by Dror et al. [9], there was no single test to confirm the diagnosis. Genotyping may be used for diagnostic confirmation, but a negative test for SBDS mutations does not exclude the diagnosis, given that 10% of SDS individuals showed no SBDS mutations [10]. An early diagnosis of SDS is necessary to monitor the risk of hematologic malignancy and supplementary therapy for clinical symptoms.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant from the Korea Health Technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (A120175).

Footnotes

No potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

References

- 1.Minelli A, Maserati E, Nicolis E, Zecca M, Sainati L, Longoni D, et al. The isochromosome i(7)(q10) carrying c.258+2t>c mutation of the SBDS gene does not promote development of myeloid malignancies in patients with Shwachman syndrome. Leukemia. 2009;23:708–711. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park SY, Chae MB, Kwack YG, Lee MH, Kim I, Kim YS, et al. Allogeneic bone marrow transplantation in Shwachman-Diamond syndrome with malignant myeloid transformation. A case report. Korean J Intern Med. 2002;17:204–206. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2002.17.3.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kwak JW, Kim S, Lim YT. A case of Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. Korean J Pediatr. 2004;47:900–903. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee JH, Bae SH, Yu JJ, Lee R, Yun YM, Song EY. A case of Shwachman-Diamond syndrome confirmed with genetic analysis in a Korean child. J Korean Med Sci. 2008;23:142–145. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2008.23.1.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nicolis E, Bonizzato A, Assael BM, Cipolli M. Identification of novel mutations in patients with Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. Hum Mutat. 2005;25:410. doi: 10.1002/humu.9324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boocock GR, Morrison JA, Popovic M, Richards N, Ellis L, Durie PR, et al. Mutations in SBDS are associated with Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. Nat Genet. 2003;33:97–101. doi: 10.1038/ng1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.den Dunnen JT, Antonarakis SE. Mutation nomenclature extensions and suggestions to describe complex mutations: a discussion. Hum Mutat. 2000;15:7–12. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(200001)15:1<7::AID-HUMU4>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Toiviainen-Salo S, Mäyränpää MK, Durie PR, Richards N, Grynpas M, Ellis L, et al. Shwachman-Diamond syndrome is associated with low-turnover osteoporosis. Bone. 2007;41:965–972. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.08.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dror Y, Donadieu J, Koglmeier J, Dodge J, Toiviainen-Salo S, Makitie O, et al. Draft consensus guidelines for diagnosis and treatment of Shwachman-Diamond syndrome. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2011;1242:40–55. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hashmi SK, Allen C, Klaassen R, Fernandez CV, Yanofsky R, Shereck E, et al. Comparative analysis of Shwachman-Diamond syndrome to other inherited bone marrow failure syndromes and genotype-phenotype correlation. Clin Genet. 2011;79:448–458. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2010.01468.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]