Abstract

Objective

To investigate the relationship between self-rated health, adjusted for standard risk factors, and myocardial infarction.

Design

Population-based prospective cohort study.

Setting

Enrolment took place between 1990 and 2004 in Västerbotten County, Sweden

Participants

Every year, persons in the total population, aged 40, 50 or 60 were invited. Participation rate was 60%. The cohort consisted of 75 386 men and women. After exclusion for stroke or myocardial infarction before, or within 12 months after enrolment or death within 12 months after enrolment, 72 530 persons remained for analysis. Mean follow-up time was 13.2 years.

Outcome measures

Cox regression analysis was used to estimate HRs for the end point of first non-fatal or fatal myocardial infarction. HR were adjusted for age, sex, systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, smoking, diabetes, body mass index, education, physical activity and self-rated health in the categories very good; pretty good; somewhat good; pretty poor or poor.

Results

In the cohort, 2062 persons were diagnosed with fatal or non-fatal myocardial infarction. Poor self-rated health adjusted for sex and age was associated with the outcome with HR 2.03 (95% CI 1.45 to 2.84). All categories of self-rated health worse than very good were statistically significant and showed a dose–response relationship. In a multivariable analysis with standard risk factors (not including physical activity and education) HR was attenuated to 1.61 (95% CI 1.13 to 2.31) for poor self-rated health. All categories of self-rated health remained statistically significant. We found no interaction between self-rated health and standard risk factors except for poor self-rated health and diabetes.

Conclusions

This study supports the use of self-rated health as a standard risk factor among others for myocardial infarction. It remains to demonstrate whether self-rated health adds predictive value for myocardial infarction in combined algorithms with standard risk factors.

Keywords: PUBLIC HEALTH, EPIDEMIOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This prospective cohort study is among the largest studies following a general population at baseline free from stroke or previous myocardial infarction.

Outcomes were strictly validated as hospital discharge diagnosis of first myocardial infarction, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD9) 410 and ICD10 I21 or a death certificate with a diagnosis of 410 or I21 as underlying cause of death without previously known myocardial infarction.

We lack information on diabetes complications at inclusion into the cohort or on any autopsy data.

Introduction

Worldwide more than 7 million peopled died of coronary heart disease in 2011.1 In Sweden, 16% of all deaths were from coronary heart disease in 2011, and of these 47% died of acute myocardial infarction (MI).2 3 There are numerous risk factors for coronary heart disease. However, most interest has been directed towards standard risk factors that can be collected from patients while visiting a physician's office; for example, age, sex, systolic blood pressure, smoking, cholesterol, diabetes and body mass index (BMI).4 5 Self-rated health, the answer to a simple question such as: “How would you rate your general health last year?”, is associated with total mortality and coronary heart disease.6 In a Danish cohort self-rated health was an independent predictor of coronary heart disease.7 The association between self-rated health and coronary heart disease has been confirmed in cohorts at baseline free from cardiovascular disease: in elderly >70 years; in a population-based cohort of persons aged 39–74 years; in women with suspected myocardial ischaemia with major cardiovascular disease as the outcome.8–10 A case–control study within the Västerbotten Intervention Programme cohort, showed a significant interaction between self-rated health and the number of biomedical risk factors present. The study was based on 78 cases of MI in the case group and 156 persons in the control group.11

We did this research because self-rated health might contribute to the set of standard risk factors that should be assessed in relation to risk prediction of coronary heart disease. Before self-rated health can be used in relation to standard risk factors there is a need to assess interaction in large prospective population studies.

The aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between self-rated health, adjusted for standard risk factors and the outcome of fatal or non-fatal MI.

Methods

Setting and study population

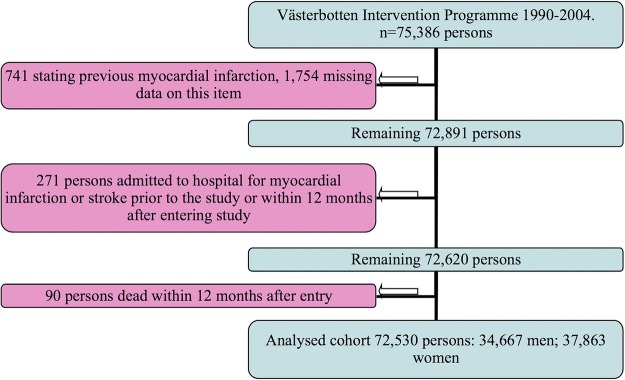

The Västerbotten Intervention Programme began in the late 1980s and is still running. It was designed to prevent premature cardiovascular disease and diabetes among the middle-aged population of Västerbotten County, Sweden. In short: all Västerbotten's residents are invited to participate in the Västerbotten Intervention Programme on reaching the age of 40, 50 or 60 years. Individuals aged 30 were invited to participate until 1995. Participation is voluntary and the participation rate gradually increased and was mean 60% during 1990–2004.12 A dropout rate analysis in 1998 indicated only a small social selection bias.12 The programme is conducted by specially trained medical personnel at local health centres. Participants completed a questionnaire and then met a nurse with whom they discussed their own risk of future cardiovascular disease on the basis of measurements of biochemical and behavioural cardiovascular disease risk factors. Participation was free of charge during the first years of the programme. Later on a fee of 100–200 Swedish Crowns (SEK) was charged (about €10–€20). Date of entry into the cohort is the date for filling in the questionnaire. The current study is based on data obtained between 1990 and 2004. The programme is described in detail elsewhere.13 The Swedish national inpatient register was followed until 31 December 2009 and the Swedish death certificate register until 31 December 2008. The total cohort consisted of 75 386 men and women. Participants were excluded if they stated at baseline that they had had hospital care for verified MI (n=741); or missing data on this item (1754); or hospital care for MI or stroke according to the Swedish national hospital discharge diagnoses register from 15 December 1986 until 12 months after entry into the cohort (n=271); or death within 12 months after entry into the cohort (n= 90). The cohort under analysis thus consisted of 72 530 men and women, see figure 1.

Figure 1.

Exclusions from the original data set of the Västerbotten Intervention Programme. Recruitment period 1990–2004.

Assessment of covariates

Covariates were assessed at baseline during a visit to the local healthcare centre. Biometrical measurements were taken including blood samples. Participants then filled in a comprehensive questionnaire covering, among other things, medical history regarding cardiovascular disease and diabetes, prior hospital care due to verified MI, educational level, physical activity in leisure time, smoking, and an assessment of self-rated health. Systolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, BMI, smoking, diabetes, age and sex were considered as standard risk factors. We added education as it is a proxy for social class and physical activity as it is a modifiable risk factor.

Outcomes and ascertainment of diagnoses

Outcome was defined by the combination of hospital discharge diagnoses of first MI or a death certificate with the underlying cause of death as MI. Diagnoses International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD9) 410, ICD10 I21 were used. A total of 1825 incident first cases of MI were registered and 335 MI deaths, totalling 2062 cases of the combined end point of fatal or non-fatal MI. Diagnoses from hospital discharges were collected from the Swedish national inpatient register. The diagnoses in the register have a validity of 98%.14 The Swedish death certificate register is based on international rules for classifications of deaths with a data programme to minimise misclassifications.12 The errors in the Swedish death certificate register are of the same magnitude as in other countries in the industrialised world with a validity of 87% for ischaemic heart disease.15

Blood pressure was measured in a recumbent position using a manual sphygmomanometer on the right mid-arm at the level of the heart after at least 5 min of rest. Two blood pressure measurements were taken, and the average systolic pressures were recorded. BMI (kg/m2) was calculated from measurements of height and weight in light indoor clothing. Cholesterol was measured on a venous blood sample obtained after an overnight fast and analysed on Reflotron bench-top analysers (Boehringer Mannheim GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). Glucose concentrations were determined after an overnight fast on capillary plasma using Reflotron bench-top analysers (Boehringer Mannheim GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) and from 2004 on a Hemocue bench-top analyser (Quest Diagnostics). All participants with fasting capillary plasma glucose below 7.0 mmol/L were offered a simplified oral glucose tolerance test according to the WHO standard.16 Participants were considered as having diabetes if they answered ‘yes’ to the question ‘Do you have diabetes?’ or had fasting plasma glucose ≥7.0 and/or 2 h plasma glucose ≥12.2 mmol/L.

For educational status, 9 years of compulsory school was classified as low, 12 years of school as medium, and postsecondary education as high education. Physical activity was assessed as sedentary if: respondents never exercised, went cycling or walking during leisure time less than 2–3 times per week, used car or bus for commuting to work, or cycled or walked to work less than 2 km each way; active if: they trained at least 2–3 times per week or went cycling or walking to work more than 5 km per way. Smoking was assessed by the question “Do you smoke at present?” with answer alternatives: “No, I have never smoked; Yes, I smoke cigarettes daily; Yes, I smoke cigars; Yes, I smoke a pipe; Yes, I smoke occasionally; Not now, but I used to smoke regularly; Not now, but previously I smoked occasionally”. All categories of smoking were used in the regression analyses but only the results for never-smokers and daily cigarette smokers are presented in the results section. The self-rated health question was formulated “How do you consider your general state of health last year?” Response alternatives were: very good, pretty good, somewhat good, pretty poor or poor.

Statistical analysis

The association between self-rated health and baseline characteristics according to table 1 was tested by using χ2 test for categorical variables and analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables. Variables were examined visually in box plot analyses and stem–leaf diagrams before testing with Cox proportional hazard regression method. Log minus log diagrams were used to ascertain the proportional hazard assumption. Interaction terms were calculated between self-rated health and variables. HR adjusted for age and sex were calculated for variables. Continuous variables were categorised in order to access linearity between the variable and HR (data not shown). A multivariable analysis with age, sex, systolic blood pressure, serum cholesterol, BMI, daily smoking of cigarettes, manifest diabetes physical activity, education and self-rated health was finally calculated (table 2). Sensitivity analysis of the final models was performed using BMI categorised in five levels. Interaction was also assessed by stratification by the five categories of self-rated health on age-adjusted and sex-adjusted HR for each variable (table 3).

Table 1.

Baseline data and outcomes in relation to self-rated health

| Self-rated health n (%) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poor | Pretty poor | Somewhat good | Pretty good | Very good | p Value for overall difference | |

| n=964 (1.3) | n=3790 (5.2) | n=15 276 (21.1) | n=33 543 (46.2) | n=18 600 (25.6) | ||

| Variable | Mean (SD)/N (per cent) | |||||

| Age, mean | 48.1 (8.9) | 48.2 (9.3) | 48.2 (9.8) | 46.3 (9.7) | 45.7 (9.4) | <0.001 |

| Men | 368 (38.2) | 1460 (38.5) | 7118 (46.6) | 16 411 (49.9) | 9185 (49.4) | |

| Women | 569 (61.8) | 2330 (61.5) | 8158 (53.4) | 17 132 (51.1) | 9415 (50.6) | <0.001 |

| Systolic BP mm Hg mean | 128.4 (18.7) | 128.4 (18.4) | 128.7 (18.4) | 126.5 (17.5) | 124.9 (16.2) | <0.001 |

| Total cholesterol mmol/L mean | 5.7 (1.3) | 5.7 (1.2) | 5.7 (1.2) | 5.6 (1.2) | 5.5 (1.2) | <0.001 |

| BMI kg/m2 mean | 26.7 (4.9) | 26.5 (4.7) | 26.4 (4.4) | 25.5 (3.9) | 24.9 (3.5) | <0.001 |

| Smoking, cigarettes daily yes/no | 225 (23.8) | 785 (21.1) | 3067 (20.4) | 5921 (17.9) | 2595 (14.2) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus yes/no | 54 (6.0) | 212 (6.0) | 837 (5.9) | 1101 (3.5) | 423 (2.4) | <0.001 |

| High educational level yes/no | 195 (20.5) | 826 (21.9) | 3027 (20.0) | 7929 (23.8) | 5224 (28.3) | <0.001 |

| Physically active yes/no | 135 (14.1) | 419 (11.1) | 1556 (10.2) | 4328 (12.9) | 3621 (19.5) | <0.001 |

| Antihypertensive treatment yes/no | 137 (14.2) | 512 (13.5) | 2000 (13.1) | 2689 (8.0) | 713 (3.8) | <0.001 |

| Fatal or non-fatal myocardial infarction | 37 (3.8) | 120 (3.2) | 578 (3.8) | 921 (2.7) | 406 (2.2) | <0.001 |

Västerbotten Intervention Programme. Recruitment period from 1990 to 2004.

BMI, body mass index; BP, blood pressure.

Table 2.

HRs in relation to outcome fatal or non-fatal myocardial infarction

| Separate Cox regression for each risk factor adjusted for sex and age |

Multivariable analysis, standard risk factors |

Multivariable analysis, including education and physical activity |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | (95% CI) | HR | (95% CI) | HR | (95% CI) | |

| Sex (female ref) | 3.20 | (2.90 to 3.50) | 3.27 | (2.94 to 3.63) | 3.24 | (2.91 to 3.61) |

| Age (years) | 1.088 | (1.082 to 1.094) | 1.068 | (1.061 to 1.074) | 1.065 | (1.058 to 1.072) |

| Systolic blood pressure | 1.014 | (1.011 to 1.016) | 1.011 | (1.008 to 1.013) | 1.011 | (1.008 to 1.013) |

| Total cholesterol | 1.32 | (1.28 to 1.37) | 1.28 | (1.23 to 1.32) | 1.27 | (1.23 to 1.32) |

| Smoker, daily cigarette (ref never-smoker) | 2.65 | (2.37 to 2.95) | 2.63 | (2.34 to 2.96) | 2.58 | (2.29 to 2.91) |

| Manifest diabetes (ref no diabetes) | 2.14 | (1.85 to 2.48) | 1.73 | (1.48 to 2.02) | 1.71 | (1.46 to 2.01) |

| BMI | 1.05 | (1.04 to 1.06) | 1.02 | (1.012 to 1.04) | 1.02 | (1.01 to 1.04) |

| Self-rated health last year poor | 2.03 | (1.45 to 2.84) | 1.61 | (1.13 to 2.31) | 1.55 | (1.08 to 2.23) |

| Self-rated health last year pretty poor | 1.56 | (1.27 to 1.91) | 1.26 | (1.01 to 1.57) | 1.18 | (0.94 to 1.48) |

| Self-rated health last year somewhat good | 1.60 | (1.41 to 1.82) | 1.36 | (1.19 to 1.56) | 1.32 | (1.15 to 1.52) |

| Self-rated health last year pretty good | 1.27 | (1.13 to 1.43) | 1.17 | (1.04 to 1.33) | 1.14 | (1.01 to 1.30) |

| Self-rated health last year very good | 1 | ref | 1 | ref | 1 | ref |

| Education short (ref=long) | 1.65 | (1.43 to 1.89) | 1.23 | (1.06 to 1.43) | ||

| Physical activity, sedentary (ref active) | 1.62 | (1.37 to 1.91) | 1.23 | (1.02 to 1.47) | ||

Separate Cox regression models for each risk factor together with sex and age and two models with multivariable analysis. Västerbotten Intervention Programme. Recruitment period from 1990 to 2004.

BMI, body mass index.

Table 3.

Stratification by self-rated health on risk factors for fatal or non-fatal myocardial infarction

| Adjusted for age and sex, HR (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HRs, outcome myocardial infarction/death in myocardial infarction, (95% CI) | |||||

| Systolic blood pressure | Total cholesterol | Smoker, daily cigarette | Manifest diabetes | BMI | |

| Self-rated health last year poor | 1.014 (0.995 to 1.032) | 1.29 (1.0 to 1.64) | 2.70 (1.01 to 7.24) | 5.55 (2.42 to 12.68) | 1.01 (0.95 to 1.08) |

| Self-rated health last year pretty poor | 1.010 (1.000. to 1.020) | 1.41 (1.23 to 1.60) | 1.75 (1.12 to 2.75) | 1.94 (1.13 to 3.34) | 1.05 (1.01 to 1.09) |

| Self-rated health last year somewhat good | 1.014 (1.010 to 1.018) | 1.27 (1.19 to 1.35) | 2.90 (2.33 to 3.61) | 2.10 (1.64 to 2.69) | 1.03 (1.01 to 1.05) |

| Self-rated health last year pretty good | 1.013 (1.009 to 1.016) | 1.28 (1.22 to 1.35) | 2.29 (1.94 to 2.70) | 2.06 (1.65 to 2.59) | 1.05 (1.04 to 1.07) |

| Self-rated health last year very good | 1.014 (1.008 to 1.020) | 1.48 (1.37 to 1.60) | 3.35 (2.62 to 4.28) | 1.52 (0.96 to 2.39) | 1.04 (1.01 to 1.07) |

Västerbotten Intervention Programme. Recruitment period from 1990 to 2004.

BMI, body mass index.

Results

The mean follow-up time for fatal or non-fatal MI was 13.2 years (SD 3.9). In total 2062 persons reached the outcome of fatal or non-fatal MI. Baseline data and outcomes in relation to self-rated health are presented in table 1. Persons in the ‘pretty good’ and ‘very good’ categories of self-rated health were younger and had a higher education. They also had lower systolic blood pressure, were leaner, had slightly lower total cholesterol, a smaller proportion of them were daily cigarette smokers and had diabetes, and there were relatively fewer fatal or non-fatal MI s in this group. All variables differed statistically significantly in relation to self-rated health categories when tested with χ2 test or ANOVA.

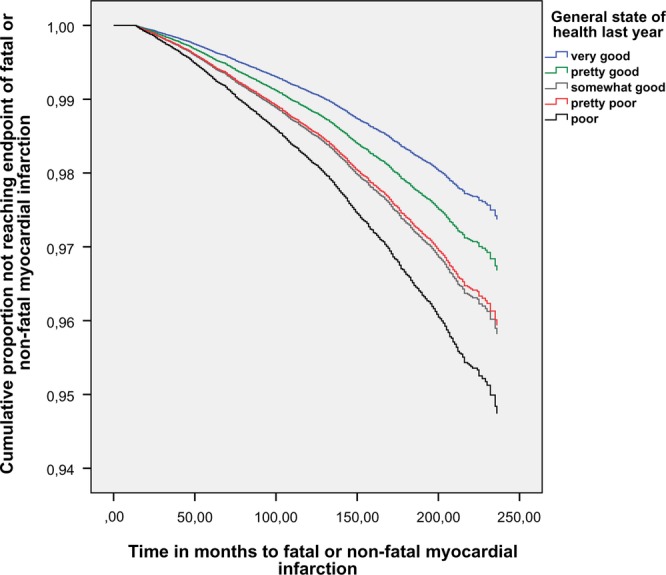

Table 2 displays crude HR for sex and age and separate Cox regression models for each risk factor adjusted for sex and age. The proportional hazards assumption was not violated. We did not stratify the data by sex as interaction terms showed no significant interaction in relation to self-rated health with p values ranging from 0.08 to 0.75 in different self-rated health categories. HRs for self-rated health ‘poor’ was 2.03 (95% CI 1.45 to 2.48) and falling according to self-rated health categories to ‘pretty poor’ 1.56 (95% CI 1.27 to 1.91); ‘somewhat good’ 1.60 (95% CI 1.41 to 1.82) and ‘pretty good’ 1.27 (95% CI 1.13 to 1.43) (see figure 2). In the multivariable analysis, for all standard risk factors HRs were attenuated except for sex. All categories of self-rated health worse than very good remained statistically significant. Adding education and physical activity further attenuated self-rated health but all categories except ‘pretty poor’ remained statistically significant, see table 2.

Figure 2.

Cumulative proportion of cohort not reaching the end point of fatal or non-fatal myocardial infarction. Västerbotten Intervention Programme. Recruitment period 1990–2004.

Time to fatal or non-fatal MI was calculated for the five categories of self-rated health. The mean times for poor, pretty poor, somewhat good, pretty good and very good were 147, 149, 154, 159 and 165 months, respectively. A scatter diagram with time to outcome and the five categories of self-rated health gave no sign of an accumulation of early outcomes in the two lowest categories of self-rated health. The sensitivity analysis using BMI, not as a continuous variable but categorised in five levels, did not alter the HRs for self-rated health.

Table 3 shows HRs for variables in the multivariable analysis of standard risk factors in table 2 stratified by self-rated health category. No notable difference can be seen except for manifest diabetes where HR is 5.55 (95% CI 2.42 to 12.68) in the category poor whereas the HR ranges from 1.52 to 2.10 in the other self-rated health categories. The interaction term for ‘poor’ and manifest diabetes was significant, p=0.011.

Discussion

Principal findings

Self-rated health is an independent predictor of fatal or non-fatal MI among standard risk factors. Adjusting for standard risk factors in a multivariable analysis attenuates HRs but a substantial relationship between self-rated health and fatal or non-fatal MI remains. The dose–response relationship between self-rated health and the outcome adds strength to the connection between self-rated health and the outcome. Self-rated health is not an effect modifier of standard risk factors for MI except for diabetes and poor self-rated health.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

The Västerbotten Intervention Programme has an attendance rate of around 60% and has internal validity. Whether the intervention has had an impact on the relation between self-rated health and the outcome has not been evaluated in this study. This study is among the largest published studies following a total population of men and women, at baseline free from major cardiovascular disease (MI or stroke) with a strictly defined end point of fatal or non-fatal MI. The combined end point of fatal, non-fatal MI covers conditions that in 1990 might have had poorer survival outcomes than in 2009, as advances in coronary intervention procedures and treatment have increased survival following MI. This allows comparison over the long timespan covered. The study is large enough to allow presentation of the five self-rated health categories in the original questionnaire as presented to the participants. The study protocol has mainly been the same since the start of the Västerbotten Intervention Programme in 1990 and the staff is well trained. We believe that the procedure of combining the questionnaire with biomedical measurements and the subsequent health discussion with a trained nurse might have contributed to the reliability in answering the questionnaire. The lack of data on high-density lipoprotein and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels could be seen as a limitation of the study. HRs are not adjusted to other factors than standard risk factors. Psychological factors and socioeconomic factors other than education were not adjusted for. These factors are important but beyond the scope of this study.

Reverse causality—that the effect of self-rated health on risk of fatal or non-fatal MI is not an effect of self-rated health—but that pre-existing disease gives low self-rated health must be considered. The quality of the registers used is high and the exclusion of patients with pre-existing MI or stroke was rigorous. Outcomes and death of any cause within a year after entry were also excluded. The mean time of 147 months (12 years) between entering the study and the outcome in the group with poor self-rated health, together with a scatter plot giving no sign of early outcomes makes a major influence of reverse causality less probable.

The out-of-hospital deaths are based on death certificates of varying quality. The autopsy frequency in Sweden is declining although around 21% of all diagnoses of MI were based on autopsy in 2004.17 Out-of-hospital deaths are often certified by general practitioners and as a rule patients who die unexpectedly without previously known cardiovascular disease are sent for autopsy. We lack information about the frequency of autopsy in this cohort. This study has not investigated the prevalence of diabetes comorbidity and functional impairment at baseline, thus not allowing exclusions of participants with diabetes with poor health at baseline. The interaction between poor self-rated health and manifest diabetes could thus be explained by reversed causation. In a recent study there was an increased HR for death in participants with diabetes with low self-rated health even when controlled for prior MI, stroke, cancer and standard risk factors.18 The authors however admit the difficulty in controlling for other potential residual confounding from comorbidity other than MI, stroke or cancer not assessed at baseline health examinations.

Findings in relation to other studies

This study confirms findings in previous studies.7 19 Self-rated health is an independent risk factor for MI or cardiovascular disease. The findings are similar to those presented by van der Linde et al9 although that study had broader, less-defined outcome categories and was smaller, covering 20 941 persons. On the other hand, it included more variables such as alcohol use, intake of vegetables and family history of MI and stroke and the numerical values of HRs were higher. This may be attributed to less well-defined cardiovascular disease, or the use of a four-grade scale of self-rated health, or a lower participation rate of 33% or contextual and semantic differences between a British and Swedish setting or an effect of the Västerbotten Intervention Programme.20 21

Self-rated health is well studied.19 22 23 To reduce its association with outcomes of fatal or non-fatal MI to negligible levels in multivariable analysis needs more than adjusting for standard risk factors. Self-rated health in itself is hardly the cause of a strict biological event such as death or MI. It is rather a statistical predictor through its ability to comprehensively account for factors important to the outcomes. There must however be a biological causative link between self-rated health and hard biological outcomes.23 Direct bodily feelings such as anxiety, depression or stress could affect both self-rated health and the physiological state of the body. There is an association between elevated levels of inflammatory markers and self-rated health.24 The association noted was not accounted for by objective health diagnoses, medication use or health behaviours. Thus self-rated health provided unique information regarding inflammatory status above and beyond traditional objective health indicators.24 In another study, allostatic load, a combined measure of physiological dysregulation, was tied to self-rated health.25 The researchers argued that self-rated health formed early in life might be an important determinant for long-term health closely tied to physiological changes in the body. These findings do not exclude a link to psychosocial association such as economic distress, unemployment or psychological factors, both protective and harmful.26 We propose that future research might follow complementary directions. First, continued research on cytokines, alterations in the body's stress system, and on allostatic load and relations to self-rated health and outcomes. Second, in the direction of emotions, symptoms and existential health where concepts such as meaning, trust, optimism, and religious activity are included and related to outcomes.27 28 The question of whether interventions aimed at improving self-rated health may improve cardiovascular health and disease-related outcomes has been raised.9 This deserves further attention.

Implications

This study gives support to the idea of including an easily assessable self-rated health question among standard risk factors of MI. No major interaction between self-rated health and other standard risk factors has been found. This information is of clinical importance. However demonstration that self-rated health adds predictive value in combined algorithms together with standard risk factors requires updated methods.29

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Göran Lönnberg for preparing the database needed for this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: GW conceived of the study and wrote the manuscript. UJ supervised the statistical and epidemiological part of the study. RL gave statistical advice, discussed results, shared in formulating syntax for SPSS22. MN supervised the use and interpretation of the Västerbotten Intervention Programme database, gave stringent advice as to the focus of the study. AF supervised the project continually, read, criticised and suggested alternative wording together with MN. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: This research was supported by the County Council of Norrbotten and the County Council of Västerbotten generously gave access to the Västerbotten Intervention Programme database.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The ethical review board at Umeå, Sweden (Dnr 08-131M).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Number of deaths: WORLD By cause [Internet]: World Health Organization. http://apps.who.int/gho/data/node.main.CODWORLD?lang=en (accessed 18 Feb 2014).

- 2.[Statistics, causes of deaths 2012.] [Internet]: The National Board of Health and Welfare. http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/statistik/statistikdatabas/dodsorsaker (accessed 4 Jun 2014).

- 3.[Statistics, causes of deaths 2012–2013-8-6.pdf] [Internet]: The National Board of Health and Welfare. http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/Lists/Artikelkatalog/Attachments/19175/2013-8-6.pdf (accessed 18 Feb 2014).

- 4.Pencina MJ, D'Agostino RB Sr, Larson MG et al. . Predicting the 30-year risk of cardiovascular disease: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2009;119:3078–84. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.816694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Kempen BJ, Ferket BS, Kavousi M et al. . Performance of Framingham cardiovascular disease (CVD) predictions in the Rotterdam Study taking into account competing risks and disentangling CVD into coronary heart disease (CHD) and stroke. Int J Cardiol 2014;171:413–18. 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.12.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Idler EL, Benyamini Y. Self-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studies. J Health Soc Behav 1997;38:21–37. 10.2307/2955359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Møller L, Kristensen TS, Hollnagel H. Self rated health as a predictor of coronary heart disease in Copenhagen, Denmark. J Epidemiol Community Health 1996;50:423–8. 10.1136/jech.50.4.423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ernstsen L, Nilsen SM, Espnes GA et al. . The predictive ability of self-rated health on ischaemic heart disease and all-cause mortality in elderly women and men: the Nord-Trondelag Health Study (HUNT). Age Ageing 2011;40:105–11. 10.1093/ageing/afq141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van der Linde RM, Mavaddat N, Luben R et al. . Self-rated health and cardiovascular disease incidence: results from a longitudinal population-based cohort in Norfolk, UK. PLoS One 2013;8:e65290 http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0065290 (accessed 13 Jun 2014). 10.1371/journal.pone.0065290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bosworth HB, Siegler IC, Brummett BH et al. . The association between self-rated health and mortality in a well-characterized sample of coronary artery disease patients. Med Care 1999;37:1226–36. 10.1097/00005650-199912000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weinehall L, Johnson O, Jansson J-H et al. . Perceived health modifies the effect of biomedical risk factors in the prediction of acute myocardial infarction. An incident case-control study from northern Sweden. J Intern Med 1998;243:99–107. 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1998.00201.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Norberg M, Blomstedt Y, Lönnberg G et al. . Community participation and sustainability-evidence over 25 years in the Västerbotten Intervention Programme. Glob Health Action 2012;5:19166 10.3402/gha.v5i0.19166 (accessed 18 May 2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Norberg M, Wall S, Boman K et al. . The Västerbotten Intervention Programme: background, design and implications. Glob Health Action 2010;3:4643 10.3402/gha.v3i0.4643 (accessed 18 May 2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A et al. . External review and validation of the Swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health 2011;11:450 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/11/450 (accessed 20 Feb 2014). 10.1186/1471-2458-11-450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johansson LA, Björkenstam C, Westerling R. Unexplained differences between hospital and mortality data indicated mistakes in death certification: an investigation of 1,094 deaths in Sweden during 1995. J Clin Epidemiol 2009;62:1202–9. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.WHO Expert Committee on diabetes mellitus. Technical report 727. Geneva: WHO, 1985. Published Online First: 8 March 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 17.[Statistics, causes of deaths 2001–2007-42-1_2007422.pdf] [Internet]. http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/Lists/Artikelkatalog/Attachments/9318/2007-42-1_2007422.pdf (accessed 5 May 2014).

- 18.Wennberg P, Rolandsson O, Jerdén L et al. . Self-rated health and mortality in individuals with diabetes mellitus: prospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000760 http://www.bmjopen.bmj.com/content/2/1/e000760 (accessed 5 May 2014). 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Latham K, Peek CW. Self-rated health and morbidity onset among late midlife U.S. adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2013;68:107–16. 10.1093/geronb/gbs104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Waller G, Thalén P, Janlert U et al. . A cross-sectional and semantic investigation of self-rated health in the northern Sweden MONICA-study. BMC Med Res Methodol 2012;12:154 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2288/12/154 (accessed 11 Oct 2012). 10.1186/1471-2288-12-154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Appels A, Bosma H, Grabauskas V et al. . Self-rated health and mortality in a Lithuanian and a Dutch population. Soc Sci Med 1996;42:681–9. 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00195-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eriksson I, Undén AL, Elofsson S. Self-rated health. Comparisons between three different measures. Results from a population study. Int J Epidemiol 2001;30:326–33. 10.1093/ije/30.2.326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jylhä M. What is self-rated health and why does it predict mortality? Towards a unified conceptual model. Soc Sci Med 2009;69: 307–16. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Christian LM, Glaser R, Porter K et al. . Poorer self-rated health is associated with elevated inflammatory markers among older adults. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2011;36:1495–504. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.04.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vie TL, Hufthammer KO, Holmen TL et al. . Is self-rated health a stable and predictive factor for allostatic load in early adulthood? Findings from the Nord Trøndelag Health Study (HUNT). Soc Sci Med 2014;117:1–9. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.07.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hasson D, Von Thiele Schwarz U, Lindfors P. Self-rated health and allostatic load in women working in two occupational sectors. J Health Psychol 2009;14:568–77. 10.1177/1359105309103576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krause N. God-mediated control and change in self-rated health. Int J Psychol Relig 2010;20:267–87. 10.1080/10508619.2010.507695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nummela O, Raivio R, Uutela A. Trust, self-rated health and mortality: a longitudinal study among ageing people in Southern Finland. Soc Sci Med 2012;74:1639–43. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.02.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pencina MJ, D'Agostino RB Sr, D'Agostino RB Jr.et al. . Evaluating the added predictive ability of a new marker: from area under the ROC curve to reclassification and beyond. Stat Med 2008;27:157–72. 10.1002/sim.2929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]