Abstract

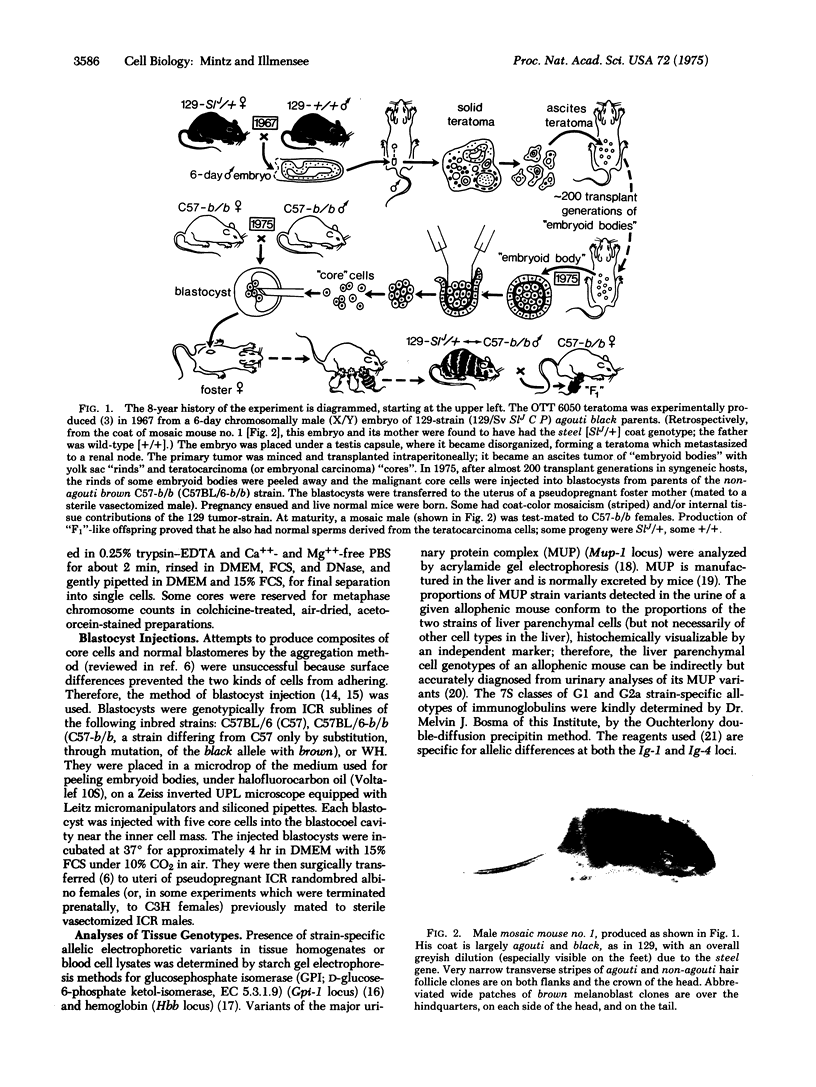

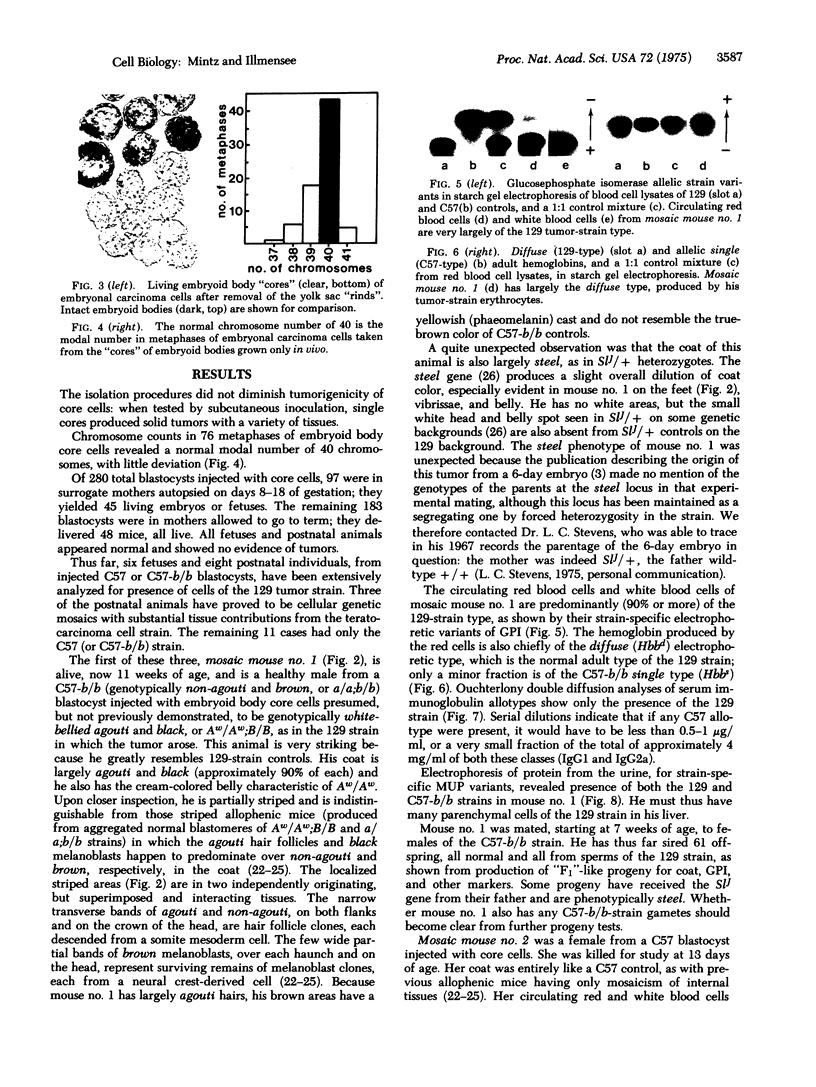

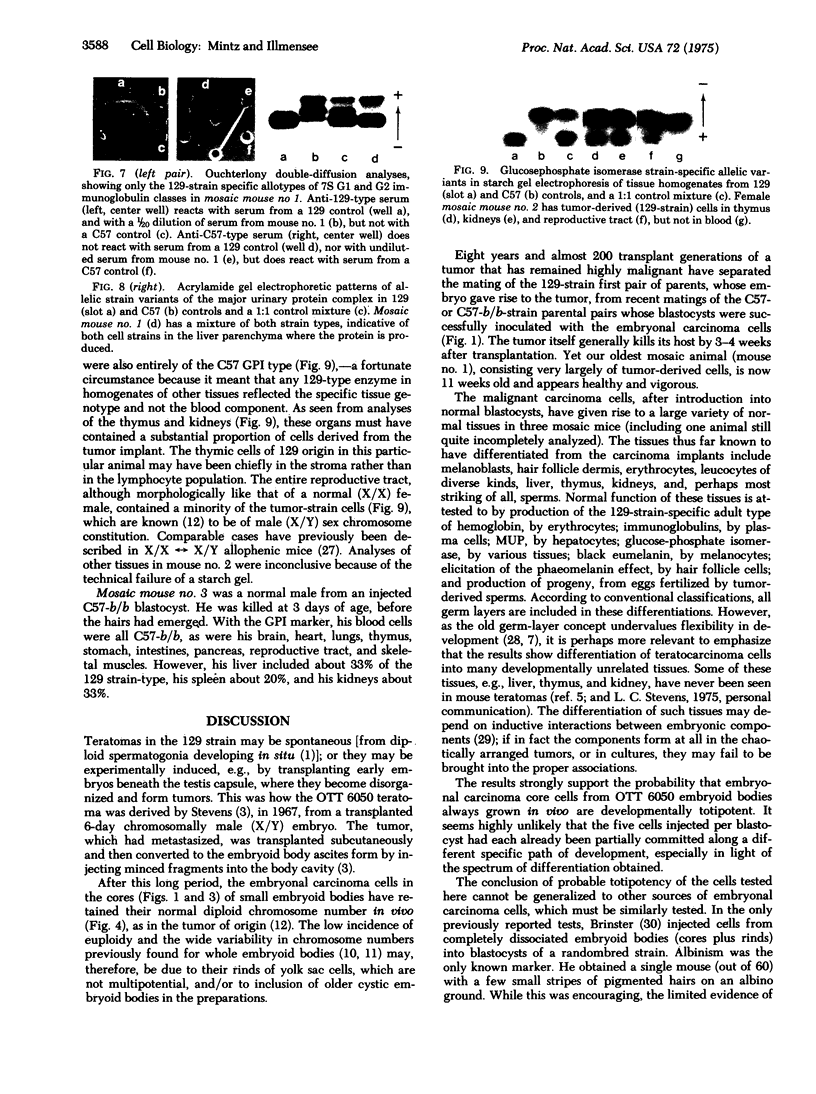

Malignant mouse teratocarcinoma (or embryonal carcinoma) cells with a normal modal chromosome number were taken from the "cores" of embryoid bodies grown only in vivo as an ascites tumor for 8 years, and were injected into blastocysts bearing many genetic markers, in order to test the developmental capacities, genetic constitution, and reversibility of malignancy of the core cells. Ninety-three live normal pre- and postnatal animals were obtained. Of 14 thus far analyzed, three were cellular genetic mosaics with substantial contributions of tumor-derived cells in many developmentally unrelated tissues, including some never seen in the solid tumors that form in transplant hosts. The tissues functioned normally and synthesized their specific products (e.g., immunoglobulins, adult hemoglobin, liver proteins) coded for by strain-type alleles at known loci. In addition, a tumor-contributed color gene, steel, not previously known to be present in the carcinoma cells, was detected from the coat phenotype. Cells derived from the carcinoma, which is of X/Y sex chromosome constitution, also contributed to the germ line and formed reproductively functional sperms, some of which transmitted the steel gene to the progeny. Thus, after almost 200 transplant generations as a highly malignant tumor, embryoid body core cells appear to be developmentally totipotent and able to express, in an orderly sequence in differentiation of somatic and germ-line tissues, many genes hitherto silent in the tumor of origin. This experimental system of "cycling" teratocarcinoma core cells through mice, in conjunction with experimental mutagenesis of those cells, may therefore provide a new and useful tool for biochemical, developmental, and genetic analyses of mammalian differentiation. The results also furnish an unequivocal example in animals of a non-mutational basis for transformation to malignancy and of reversal to normalcy. The origin of this tumor from a disorganized embryo suggests that malignancies of some other, more specialized, stem cells might arise comparably through tissue disorganization, leading to developmental aberrations of gene expression rather than changes in gene structure.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bosma M. J., Bosma G. C. Congenic mouse strains: the expression of a hidden immunoglobulin allotype in a congenic partner strain of BALB-c mice. J Exp Med. 1974 Mar 1;139(3):512–527. doi: 10.1084/jem.139.3.512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brinster R. L. The effect of cells transferred into the mouse blastocyst on subsequent development. J Exp Med. 1974 Oct 1;140(4):1049–1056. doi: 10.1084/jem.140.4.1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condamine H., Custer R. P., Mintz B. Pure-strain and genetically mosaic liver tumors histochemically identified with the -glucuronidase marker in allophenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1971 Sep;68(9):2032–2036. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.9.2032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn G. R., Stevens L. C. Determination of sex of teratomas derived from early mouse embryos. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1970 Jan;44(1):99–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans M. J. The isolation and properties of a clonal tissue culture strain of pluripotent mouse teratoma cells. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1972 Aug;28(1):163–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlayson J. S., Asofsky R., Potter M., Runner C. C. Major urinary protein complex of normal mice: origin. Science. 1965 Aug 27;149(3687):981–982. doi: 10.1126/science.149.3687.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner R. L. Mouse chimeras obtained by the injection of cells into the blastocyst. Nature. 1968 Nov 9;220(5167):596–597. doi: 10.1038/220596a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gearhart J. D., Mintz B. Clonal origins of somites and their muscle derivatives: evidence from allophenic mice. Dev Biol. 1972 Sep;29(1):27–37. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(72)90040-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gearhart J. D., Mintz B. Contact-mediated myogenesis and increased acetylcholinesterase activity in primary cultures of mouse teratocarcinoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1974 May;71(5):1734–1738. doi: 10.1073/pnas.71.5.1734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakob H., Boon T., Gaillard J., Nicolas J., Jacob F. Tératocarcinome de la spuris: isolement, culture et propriétés de cellules a potentialités multiples. Ann Microbiol (Paris) 1973 Oct;124(3):269–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KLEINSMITH L. J., PIERCE G. B., Jr MULTIPOTENTIALITY OF SINGLE EMBRYONAL CARCINOMA CELLS. Cancer Res. 1964 Oct;24:1544–1551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahan B. W., Ephrussi B. Developmental potentialities of clonal in vitro cultures of mouse testicular teratoma. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1970 May;44(5):1015–1036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman J. M., Speers W. C., Swartzendruber D. E., Pierce G. B. Neoplastic differentiation: characteristics of cell lines derived from a murine teratocarcinoma. J Cell Physiol. 1974 Aug;84(1):13–27. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1040840103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin T. P. Microinjection of mouse eggs. Science. 1966 Jan 21;151(3708):333–337. doi: 10.1126/science.151.3708.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mintz B. Gene control of mammalian differentiation. Annu Rev Genet. 1974;8:411–470. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.08.120174.002211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mintz B. Gene control of mammalian pigmentary differentiation. I. Clonal origin of melanocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1967 Jul;58(1):344–351. doi: 10.1073/pnas.58.1.344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RANNEY H. M., SMITH G. M., GLUECKSOHN-WAELSCH S. Haemoglobin differences in inbred strains of mice. Nature. 1960 Oct 15;188:212–214. doi: 10.1038/188212a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STEVENS L. C., HUMMEL K. P. A description of spontaneous congenital testicular teratomas in strain 129 mice. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1957 May;18(5):719–747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens L. C. The biology of teratomas. Adv Morphog. 1967;6:1–31. doi: 10.1016/b978-1-4831-9953-5.50005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox F. H. Simplified procedure for electrophoresis of the major urinary protein of Mus musculus. Biochem Genet. 1975 Apr;13(3-4):243–245. doi: 10.1007/BF00486018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]