Abstract

We present a case of a man who suffered bilateral neck of femur fractures secondary to osteomalacia, attributable to a combination of his reclusive lifestyle, poor diet and long-term anticonvulsant therapy. These fractures may have been prevented if certain risk factors had been identified early. This case aims to highlight the importance of identifying vulnerable older adults in the community who are at risk of fragility fractures secondary to osteomalacia. It should be recognised that not only osteoporosis but other factors can precipitate these fractures as well and that preventative measures should be undertaken in those individuals at risk.

Background

Osteomalacia, either primary or secondary, is characterised by defective bone mineralisation. The most common cause is vitamin D deficiency. It largely affects the elderly and is frequently overlooked. Britain has an increasingly ageing population with many older people being housebound and having poor diets. The prevalence of epilepsy in those over 65 within the UK is approximately 1%,1 2 with anticonvulsant prescription in these patients being the same as in younger adults.3

Several studies have suggested an association between anticonvulsant use and an increased risk of fracture, due to reduced bone mineral density.4–8 The combination of a poor diet, reduced sunlight exposure and chronic anticonvulsant use leaves a significant number of our elderly population at risk of fragility fractures. It is important for these individuals to be identified as being at risk in order to prevent these fractures and their associated morbidity.

Case presentation

We present a case of a 66-year-old man with epilepsy, taking carbamazepine for 13 years, with no other significant medical history and on no other regular medications. He had a very poor dietary (including calcium) intake and, although he was mobile, spent his time almost exclusively indoors, living a reclusive lifestyle. He was brought to the accident and emergency department following a seizure. He was cachectic, dehydrated, unkempt and unable to weight bear. X-rays confirmed bilateral neck of femur fractures (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Bilateral femoral neck fractures following seizure.

Investigations demonstrated raised parathyroid hormone levels (631 pg/mL, normal range (nr) 15–65), with low vitamin D (25 ng/mL, nr 50–100) and adjusted calcium (1.87 mmol/L, nr 2.2–2.6) levels. Creatinine was 231 μmol/L (nr 64–104) and urea 25.1 mmol/L (nr 2.5–7.8). There had been no history of previous renal dysfunction. Alkaline phosphatase was raised at 480 U/L (nr 35–120) in isolation to normal remaining liver function tests. Magnesium, phosphate and prostate-specific antigen levels were all normal as was a myeloma screen. Carbamazepine level was also within normal range at 8.7 mg/L. CT of the chest, abdomen and pelvis was unremarkable for malignancy, however, it revealed fractures of the thoracic ribs and spine in addition to showing femoral neck fractures.

Calcium and vitamin D were replaced prior to the insertion of bilateral femoral nails (figure 2) along with active fluid resuscitation. The patient made an uncomplicated recovery and was discharged on calcium and vitamin D supplementation in addition to carbamazepine. A bone densitometry dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scan performed following discharge indicated some evidence of osteoporosis within the lumbar spine and forearm in addition to the evident osteomalacia.

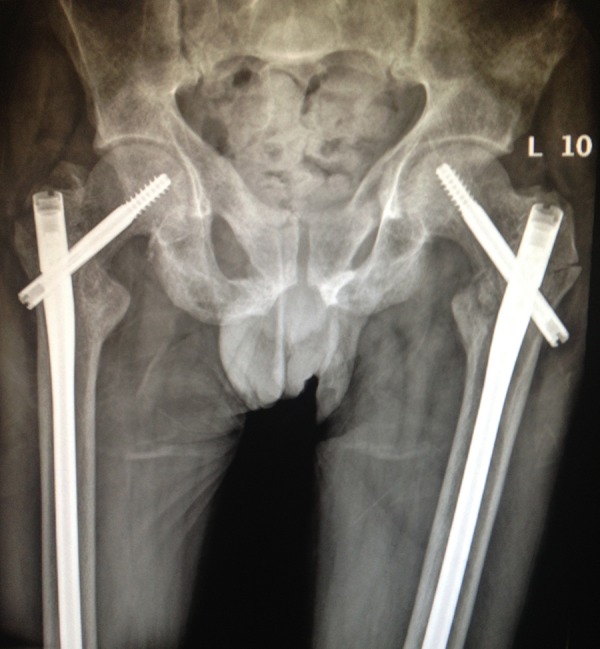

Figure 2.

Postbilateral femoral nail insertion.

Discussion

It is thought that this patient's decreased vitamin D levels were secondary to a combination of poor dietary intake and decreased sunlight exposure, as well as long-term anticonvulsant use. This led to hypocalcaemia precipitating a seizure and resultant bilateral femoral neck fractures secondary to decreased bone mineral density. The acute renal dysfunction, which resolved with rehydration, may have potentiated these findings; however, it is unlikely to have been a major contributor to the acute presentation of seizure and hypocalcaemia.

Bilateral neck of femur fractures usually occur as a result of high impact trauma. Occurrence has been reported previously, secondary to electroconvulsive and pharmacoconvulsive therapy, however, it has become less prevalent since the initiation of the use of muscle relaxants during these procedures. A recent article described these fractures following a tonic–clonic seizure, however, the patient underwent bilateral hip hemiarthroplasties.9 There do not appear to be reports in the literature relating to bilateral neck of femur fractures owing directly to osteomalacia as a result of anticonvulsant use, poor dietary intake and a reclusive lifestyle.

A large proportion of the elderly may be housebound with poor oral intake, leading to vitamin D deficiency. Factors such as severe liver failure, early renal failure and long-term anticonvulsant use may precipitate osteomalacia due to defective vitamin D homoeostasis, ultimately decreasing calcium availability for bone mineralisation. Osteomalacia is often neglected and regarded as a disease that has almost been eradicated. Osteoporosis is projected as the key risk factor for fragility fractures, and active prophylactic measures are implemented to reduce its associated morbidity. However, it is important to recognise that osteomalacia is still prevalent and that certain individuals, as highlighted by our case, are at increased risk. This may be posing an unrecognised burden on the health service and therefore should be identified within the community and treated accordingly. Failure to recognise this condition will result in these frail individuals presenting with preventable fractures and having to undergo painful prolonged rehabilitation.

Learning points.

Healthcare professionals must be made aware of the risk factors for osteomalacia, in particular general practitioners.

Vulnerable adults in the community, at risk of fragility fractures secondary to both osteoporosis and osteomalacia, should be identified.

Support to those identified at risk should be provided in the form of vitamin D and calcium supplementation, and by ensuring adequate nutritional intake and regular medication review, in particular for those taking anticonvulsant therapy.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Purcell B, Gaitatziz A, Sander JW et al. . Epilepsy prevalence and prescribing patters in England and Wales. Office of National Statistics, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tallis R, Hall G, Craig I et al. . How common are epileptic seizures in old age? Age Aging 1991;20:442–8. 10.1093/ageing/20.6.442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE). The epilepsies: the diagnosis and management of the epilepsies in adults and children in primary and secondary care. Clinical guideline 20. London: NICE, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pack AM, Morrell MJ. Adverse effects of antiepileptic drugs on bone structure: epidemiology, mechanisms and therapeutic implications. CNS Drugs 2001;15:633–42. 10.2165/00023210-200115080-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pack AM, Gidal B, Vazquez B. Bone disease associated with antiepileptic drugs. Cleve Clin J Med 2004;71(Suppl 2):S42–8. 10.3949/ccjm.71.Suppl_2.S42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vestergaard P, Rejnmark L, Mosekilde L. Fracture risk associated with use of antiepileptic drugs. Epilepsia 2004;45:1330–7. 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2004.18804.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dent CE, Richens A, Rowe DJ et al. . Osteomalacia with long-term anticonvulsant therapy in epilepsy. BMJ 1970;4:69–72. 10.1136/bmj.4.5727.69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee RH, Lyles KW, Colón-Emeric C. A review of the effect of anticonvulsant medications on bone mineral density and fracture risk. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother 2010;8:34–46. 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2010.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brennan SA, O'Neill CJ, Tarazi M et al. . Bilateral neck of femur fractures secondary to seizure. Pract Neurol 2013;13:420–1. 10.1136/practneurol-2013-000669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]