Abstract

Subtle mood fluctuations are normal emotional experiences, whereas drastic mood swings can be a manifestation of bipolar disorder (BPD). Despite their importance for normal and pathological behavior, the mechanisms underlying endogenous mood instability are largely unknown. During embryogenesis, the transcription factor Otx2 orchestrates the genetic networks directing the specification of dopaminergic (DA) and serotonergic (5-HT) neurons. Here we behaviorally phenotyped mouse mutants overexpressing Otx2 in the hindbrain, resulting in an increased number of DA neurons and a decreased number of 5-HT neurons in both developing and mature animals. Over the course of 1 month, control animals exhibited stable locomotor activity in their home cages, whereas mutants showed extended periods of elevated or decreased activity relative to their individual average. Additional behavioral paradigms, testing for manic- and depressive-like behavior, demonstrated that mutants showed an increase in intra-individual fluctuations in locomotor activity, habituation, risk-taking behavioral parameters, social interaction, and hedonic-like behavior. Olanzapine, lithium, and carbamazepine ameliorated the behavioral alterations of the mutants, as did the mixed serotonin receptor agonist quipazine and the specific 5-HT2C receptor agonist CP-809101. Testing the relevance of the genetic networks specifying monoaminergic neurons for BPD in humans, we applied an interval-based enrichment analysis tool for genome-wide association studies. We observed that the genes specifying DA and 5-HT neurons exhibit a significant level of aggregated association with BPD but not with schizophrenia or major depressive disorder. The results of our translational study suggest that aberrant development of monoaminergic neurons leads to mood fluctuations and may be associated with BPD.

INTRODUCTION

Subtle mood swings are normal experiences of healthy individuals, whereas extreme mood swings are a hallmark of bipolar disorder (BPD; Belmaker, 2004). There is a substantial genetic contribution to the risk of BPD that does not follow any of the simple mendelian patterns of inheritance. On the basis of genome-wide association studies (GWAS), various individual susceptibility genes for BPD have been suggested (Craddock and Sklar, 2013), although the specific molecular pathways in which these genes operate in BPD are not known. Recently developed pathway-based GWAS analysis tools have enabled identification of genetic variants of groups of genes that interact in a particular biological process and that have a significant joint effect on BPD (Lee et al, 2012; Wang et al, 2007). In these studies, genes critical for neural development were identified, including members of the Wnt signaling pathway (Pandey et al, 2012; Pedroso et al, 2012; Zandi et al, 2008). A key challenge remaining is the translation of established genetic associations into a better pathophysiological understanding of BPD.

The difficulties to model the complex symptomatology of BPD in animals have been a major obstacle for investigating the neurobiology of this condition. Although different models mimic manic- or depressive-like behavior (Dao et al, 2010; Engel et al, 2009; Han et al, 2013; Roybal et al, 2007; Shaltiel et al, 2008), few animal paradigms provide insights into the major characteristics of BPD, emotional lability, and behavioral fluctuations. Overexpressing glucocorticoid receptors in the forebrain of mice leads to depressive-like behavior, supersensitivity to antidepressants, and enhanced sensitization for cocaine, indicating that emotional lability can be caused by aberrant glucocorticoid signaling (Wei et al, 2004). Neuron-specific accumulation of mitochondrial DNA mutations leads to estrous cycle-dependent periodic changes in locomotor activity patterns in females, which are reversed by ovariectomy or exposure to chronic lithium (Kasahara et al, 2006). In male mice, these mitochondrial changes do not lead to behavioral fluctuations. However, spontaneous fluctuations in manic- and depressive-like behavior have not been modeled (Chen et al, 2010; Kara and Einat, 2013; Nestler and Hyman, 2010).

On the basis of suggested mechanisms of action of BPD medications, a complex imbalance of dopamine and serotonin, here referred to as monoamines, is thought to have a critical role in this condition (Beaulieu, 2012; Lesch and Waider, 2012). Although different lines of evidence have suggested the importance of neurodevelopmental alterations in BPD (Ayhan et al, 2011; Sanches et al, 2008), a role for monoaminergic neuron development in mood instability and BPD has not previously been described. The major dopaminergic (DA) and serotonergic (5-HT) neuronal populations develop as neighboring cell groups at the embryonic mid–hindbrain junction. The DA neurons form in the midbrain and the 5-HT neurons originate adjacently in the hindbrain (Brodski et al, 2003). We previously reported that the transcription factor Otx2, together with Wnts and their signaling molecules, regulate genetic pathways controlling the specification of monoaminergic neurons. Otx2, expressed in the midbrain with a sharp boun7dary to the hindbrain, induces the formation of DA neurons and represses generation of 5-HT neurons (Brodski et al, 2003; Omodei et al, 2008; Prakash et al, 2006). Interestingly, Otx2 as well as Wnt pathway members have been proposed as susceptibility genes for BPD (Pandey et al, 2012; Pedroso et al, 2012; Sabunciyan et al, 2007; Zandi et al, 2008).

Mouse mutants expressing Otx2 under the endogenous promoter of En1, active in a strip on either side of the mid–hindbrain junction, ectopically express Otx2 in the hindbrain (En1+/Otx2). These changes result in an increase in the number of specified DA neurons and a complementary reduction in the number of specified 5-HT neurons. Despite changes in cell numbers, monoaminergic neurons migrate and project normally in these animals (Brodski et al, 2003). Transmitter measurements, transporter binding assays, and autoradiography all indicate a subtle increase in striatal DA innervation and a marked general decrease of 5-HT innervation in adult mutants (Brodski et al, 2003; Tilleman et al, 2009). Behaviorally, En1+/Otx2 mutants are hyperactive and exhibit more stereotyped behavior (Tilleman et al, 2009), as do amphetamine-treated wild-type mice, a predominant model for one domain of manic-like behavior (Chen et al, 2010; Gould et al, 2007; Kara and Einat, 2013; Nestler and Hyman, 2010).

In this study, we employed En1+/Otx2 mutants to investigate how aberrant development of monoaminergic neurons results in manic- and depressive-like behavior. These animals are particularly well suited to address this question due to their well-characterized changes in monoaminergic neurons, in both developing and mature animals. In addition, we describe here our application of a pathway enrichment tool for GWAS (Lee et al, 2012) to test the relevance of our preclinical findings for BPD in humans.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

As a control for En1+/Otx2 mutants, wild-type littermates (WT) were used. All behavioral experiments were performed on 3- to 6-month-old males, previously single caged for at least 1 week. The apparatus, animal handling, and working protocols are described in detail in the Supplementary Methods. All procedures and experiments with the animals were conducted in accordance with Ethics Committee approval IL-13-03-2010, BGU.

Pharmacological Treatment

Lithium and carbamazepine were mixed in food, whereas olanzapine, quipazine, and CP-809,101 were administered to the animals by 10 ml/kg IP injections. Treatment, doses, and protocols are described in detail in the Supplementary Methods.

Behavioral Tests

Behavioral tests are described in detail in the Supplementary Methods.

Statistical Analysis

All results are expressed as mean±SE. A two-tailed unpaired Student's t-test, two-way multifactorial analysis of variance (ANOVA test), Fisher's LSD post hoc analysis, and false discovery rate (FDR) were used and described in the Supplementary Methods.

INRICH Pathway Analysis

We used the interval-based pathway analysis software (INRICH) as previously described (Lee et al, 2012). The parameters used for the analysis are described in detail in the Supplementary Methods.

RESULTS

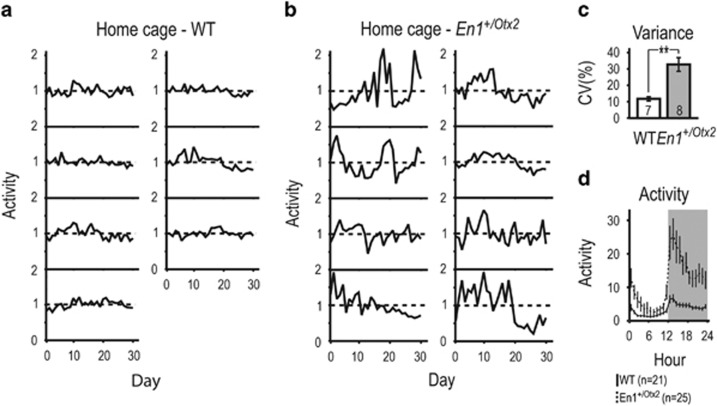

En1 +/Otx2 Mutants Show Extended Periods of Increased or Reduced Activity Relative to their Individual Average

First, we studied the activity of En1+/Otx2 mutants in their home cage, using surgically implanted telemetry activity probes, during a normal light–dark cycle of 12 h. Individual WT animals maintained a similar level of locomotor activity throughout the observed 30-day period (Figure 1a). In contrast, En1+/Otx2 mutants exhibited extended periods of increased and decreased activity, each animal compared with its individual average activity level (Figure 1b). Fluctuations were quantified by assessing the coefficient of variation (CV), calculated by dividing the SD of the mean activity of each individual animal by its mean activity (Lucki et al, 2001; Fontana et al, 2014). Mutants showed a significantly higher CV compared with controls (Figure 1c). Increased CV for mutants was also observed under conditions of constant darkness (Supplementary Figure 1). En1+/Otx2 mutants were hyperactive during the dark phase and showed increased vigilance at the beginning and end of the light phase (Figure 1d). Taken together, En1+/Otx2 mutants show increased intra-individual changes in their spontaneous activity levels over time.

Figure 1.

En1+/Otx2 mutants show increased intra-individual fluctuations in spontaneous locomotor activity in their home cage. Animal activity for each day was recorded for 30 days, normalized to the average activity level of that animal during the entire period, and shown as a function of day in separate plots for each (a) WT and (b) En1+/Otx2 mutant animal. (c) En1+/Otx2 mutants showed increased intra-individual fluctuation as indicated by increased CV (t13=4.468, p=0.001). Mutants showed (d) increased locomotor activity (GenotypeF1,44=17.152, p<0.001) with a significantly different profile of activity (Genotype*HourF23=5.674, p<0.001). Two-tailed unpaired Student's t-test: **p<0.01.

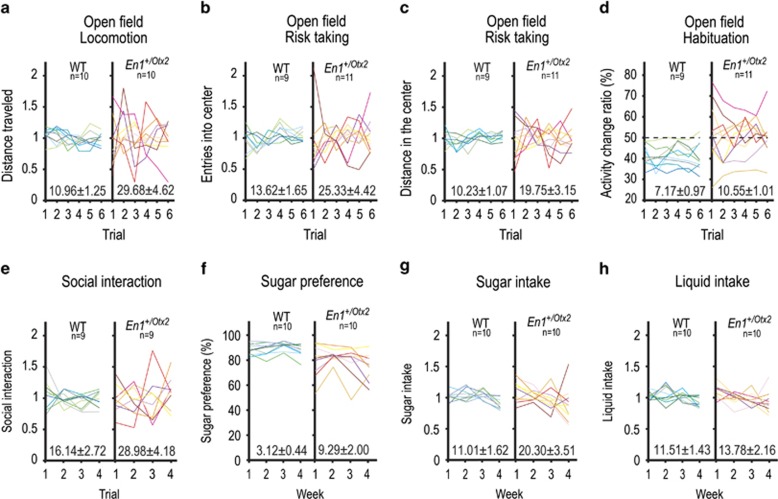

En1+/Otx2 Mutants Exhibit Increased Intra-Individual Fluctuation in Activity, Habituation, Risk-Taking Behavior, Sociability, and Hedonic-Like Behavior

To further study behavioral fluctuations of En1+/Otx2 mutants, we repetitively exposed animals to the open-field test (OFT). We assessed locomotor activity as well as risk-taking behavior in WT and En1+/Otx2 mutants by measuring the ratio (center vs total) of distance traveled as well as the number of entries into the center of the OFT. CVs for locomotor activity and risk-taking parameters were increased in the En1+/Otx2 mice compared with controls (Figure 2a–c). Mutants were more active and entered into the center more than controls, while the percentage of the distance traveled in the center did not significantly differ between the genotypes (Supplementary Figure 2a). The activity was correlated with the risk-taking behavior in mutants stronger than in controls and it was not correlated with the CV for both the mutants and the controls (Supplementary Figure 3a and c). We then quantified intra-session habituation of En1+/Otx2 mutants using the activity change ratio (ACR; see Supplementary Methods). The CV for ACRs of the mutant mice was significantly increased (Figure 2d). WTs consistently had ACRs below 50%, indicating that they habituate during the OFT session. In contrast, the most active En1+/Otx2 mutants had ACRs of 50% or more, indicating that they either failed to habituate or increased locomotion (Supplementary Figure 3b).

Figure 2.

En1+/Otx2 mutants show increased fluctuations in different behavioral paradigms. Individual animals are represented by different lines in the separate graphs for mutants and controls. CV±SE was calculated and shown above x axis of the graph of both genotypes. Animal activity was recorded for 1 h in the OFT for six consecutive trials over 3 weeks (a–d). En1+/Otx2 animals exhibited increased CV for (a) activity levels (t18=3.029, p=0.007), (b) the percentage of entries into the center (t18=2.482, p=0.028), and (c) the percentage of the total distance they traveled in the center (t18=2.864, p=0.014). CV for En1+/Otx2 mutants was also increased for (d) ACRs (t18=2.38, p=0.027). In the social interaction test, animals of the same genotype were recorded for 5 min in four consecutive trials over 2 weeks. Fluctuation in the time animals interacted was calculated for four trials, following one initial habituation trial. Mutants (e) showed an increased CV for the time they interacted (t16=2.572, p=0.020). Variance in sucrose preference was measured during the course of 4 weeks. As quantified by an increase in the CV, more fluctuations were observed in mutants over time for (f) sucrose preference (t18=3.017, p=0.007) and (g) sucrose intake (t18=2.398, p=0.028) but not for (h) total liquid intake (t18=0.879, p=0.391).

Social interaction test was used in the OFT to compare variations in sociability of mutants and WT mice. En1+/Otx2 mutants showed an increased CV for the time they engaged in social interaction (Figure 2e), whereas the time they spent in social interaction was decreased compared with the WTs (Supplementary Figure 2b).

To study hedonic-like behavior, we employed the sucrose preference test. Both WTs and mutants demonstrated sucrose preference for a 2 and 5% solution. However, the sucrose preference in the mutant mice was lower compared with WTs (Supplementary Figure 2c). Their CV was increased for sucrose preference and sucrose intake, but not for total liquid intake compared with controls for the 2% (Figure 2f–h) and the 5% sucrose concentration (t18=3.458, p=0.003; t18=3.029, p=0.001; t18=3.029, p=0.108). Taken together, En1+/Otx2 mutants show a mixed state of manic- and depressive-like behaviors, fluctuating over time.

En1+/Otx2 Mutants Show Increased Manic-Like Behavior that can be Ameliorated by Acute Olanzapine Treatment

Anxiety-like/risk-taking behavior was studied in the elevated plus maze (EPM) and light–dark box (LDB). As these tests cannot be repetitively applied without diminishing validity, each animal was exposed to them only once. En1+/Otx2 mice showed consistently decreased anxiety-like behavior/increased risk-taking behavior. In the EPM, mutants exhibited proportional (open arm vs all arms) increase in open-arm entries and duration (Supplementary Figure 2d). Mutants also spent more time in the light compartment of the LDB (Supplementary Figure 2e).

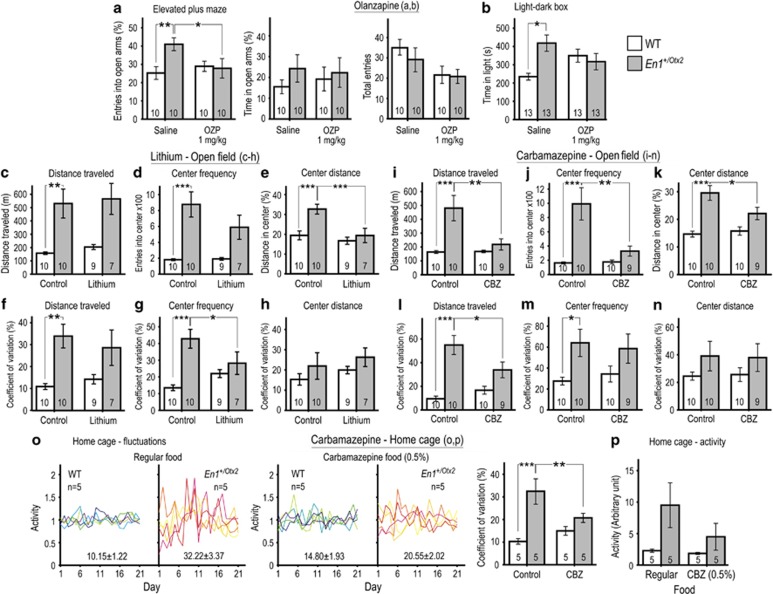

We then tested whether olanzapine exposure, used as an acute treatment for mania, can improve behavioral alterations of En1+/Otx2 mutants. Acute olanzapine treatment selectively reduced the percentage of entries into open arms for En1+/Otx2 mutants, but not for WT mice (Figure 3a). There was no interaction between genotype and treatment for the percentage of time animals spent in the open arms (Figure 3a). Olanzapine also decreased the number of entries into all arms of the EPM, with no significant difference in effect between groups (Figure 3a). In the LDB, a significant interaction between genotype and olanzapine treatment in the time spent in the light compartment was detected (Figure 3b). In the OFT, olanzapine decreased activity and the number of entries into the center and increased ACRs for both WT and En1+/Otx2 mutants, with no differential effect on genotypes (Supplementary Figure 4). Overall, acute olanzapine treatment attenuated manic-like behavior of mutants.

Figure 3.

Olanzapine, lithium, and carbamazepine improve behavioral parameters in En1+/Otx2 mutants. Behavioral tests were conducted 1 h after IP injection of vehicle or 1 mg/kg olanzapine. In the EPM, (a) the increase in ratios of open arm vs total (open and closed arms) in mutants was reversed by acute treatment with olanzapine (Genotype*TreatmentF1,36=4.663, p=0.038; Fisher's LSD post hoc test, p=0.022). There was no interaction between genotype and treatment for the percentage of time animals spent in the open arms (Genotype*TreatmentF1,36=0.251, p=0.619). Number of entries to all arms was decreased by olanzapine treatment (Genotype*TreatmentF1,36=6.065, p=0.019). This did not differ for WTs and mutants (Genotype*TreatmentF1,36=0.335, p=0.566). In the LDB, a significant interaction between genotype and olanzapine treatment in (b) the time spent in the light compartment was detected (Genotype*TreatmentF1,48=5.666, p=0.005). Animals were treated with lithium for 4 weeks before being exposed to six consecutive trials in the OFT over 3 weeks. Lithium did not significantly reduce (c) locomotor activity (Genotype*TreatmentF1,31=0.005, p=0.942) and (d) the number of entries into the center of the OFT in mutants (Genotype*TreatmentF1,31=1.794, p=0.190), whereas for the distance traveled in the center (e), it resulted in a significant reduction (Genotype*TreatmentF1,31=4.291, p=0.047; Fisher's LSD post hoc test, p=0.001). (f) Lithium treatment did not affect the CV for locomotor activity in mutants (Genotype*TreatmentF1,31=0.856, p=0.362), while reducing it selectively for the frequency of entries into the center (g; Genotype*TreatmentF1,31=6.544, p=0.016; Fisher's LSD post hoc test, p=0.032). There was no interaction between lithium treatment and genotype in CV for the distance traveled in the center (h; Genotype*TreatmentF1,31=0.001, p=0.947). Animals were treated with carbamazepine for 2 weeks before being exposed to four consecutive trials in the OFT over 2 weeks. Carbamazepine selectively reduced (i) locomotor activity (Genotype*TreatmentF1,35=6.732, p=0.014; Fisher's LSD post hoc test, p=0.001); (j) frequency of entries (Genotype*TreatmentF1,35=7.679, p=0.009; Fisher's LSD post hoc test, p<0.001), and (k) distance traveled in the center (Genotype*TreatmentF1,35=4.696, p=0.037; Fisher's LSD post hoc test, p=0.032) of the OFT in mutants. The CV was significantly reduced in mutants for their locomotor activity (l; Genotype*TreatmentF1,35=6.462, p=0.016; Fisher's LSD post hoc test, p=0.012), whereas a reduction was not observed for (m) frequency of entries (Genotype*TreatmentF1,35=0.358, p=0.553) and (n) distance traveled in the center of the OFT (Genotype*TreatmentF1,35=0.021, p=0.887). Although exposed to carbamazepine, daily activity of animals was recorded for 21 days, normalized to the average activity of that animal, and shown as a function in different color for each animal in separate plots for different groups. The CV±SE is calculated and shown for each group above x axis of the graph representing that group. (o) Chronic carbamazepine treatment selectively reduced the elevated CVs of mutants (Genotype*TreatmentF1,16=12.932, p=0.002; Fisher's LSD post hoc test, p=0.002), while the reduction of the hyperactivity in mutants did not reach statistical significance (p; Genotype*TreatmentF1,16=1.213, p=0.287). Fisher's LSD post hoc test: *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

Chronic Lithium and Carbamazepine Treatments Improve Abnormal Behavior of En1+/Otx2 Mutants

To test the effects of mood-stabilizing drugs on En1+/Otx2 mutants, we studied whether their behavioral alterations can be reversed by the chronic treatment with lithium and carbamazepine. The effect of lithium in the standard mouse mania model, based on ampetamine-induced hyperlocomotion, is strongly strain dependent (Gould et al, 2007). CD-1 mice were shown to not respond to lithium in this paradigm (Gould et al, 2007). As all of the experiments described above were performed on mutants maintained on a CD-1 genetic background, we investigated the effect of lithium on these animals. En1+/Otx2 mice on a CD-1 genetic background did not show response to chronic lithium treatment with regard to their locomotor activity and risk-taking parameters in the OFT experiments (data not shown).

The Black Swiss (BS) mouse strain responds to lithium in the ampetamine-induced hyperlocomotion paradigm and has been previously suggested to model aspects of mania (Flaisher-Grinberg and Einat, 2010). Therefore, we backcrossed En1+/Otx2 mutants for six generations to a BS genetic background and used these mice for the lithium and carbamazepine treatment experiments in the OFT (Figure 3c–n). Behavioral fluctuations in the OFT were preserved in mutants with this genetic background (Supplementary Figure 5).

Chronic lithium treatment in mutants significantly reduced the percentage of the distance traveled in the center (Figure 3e), while mutants did not exhibit significantly decreased activity (Figure 3c) and frequency of entries into the center of the OFT (Figure 3d). Treatment with lithium selectively decreased the CV for the frequency of entries into the center of the OFT (Figure 3g). There was no interaction between genotype and treatment in CV for locomotor activity (Figure 3f) or for the percentage of distance traveled in the center (Figure 3h).

Carbamazepine selectively reduced locomotor activity, frequency of entries, and percentage of distance traveled in the center of the OFT in mutants (Figure 3i–k). The CV was significantly reduced in mutants for locomotor activity (Figure 3l), whereas a reduction was not observed for frequency of entries and percentage of distance traveled in the center of the OFT (Figure 3m and n). In summary, chronic treatment with lithium and carbamazepine ameliorates aspects of altered behavior observed in mutants on the BS genetic background.

Next we studied the effects of chronic carbamazepine treatment on the fluctuations in mutants using the high temporal resolution provided by the telemetry data acquisition system under the conditions used for the experiment described in Figure 1 (home cage activity, constant data recording, and animals on CD-1 genetic background). Chronic carbamazepine treatment attenuated the fluctuation in the activity of the mutants as demonstrated by a specific reduction in CV for the activity in mutants over time (Figure 3o), while the reduction in the hyperactivity in mutants did not reach statistical significance (Figure 3p).

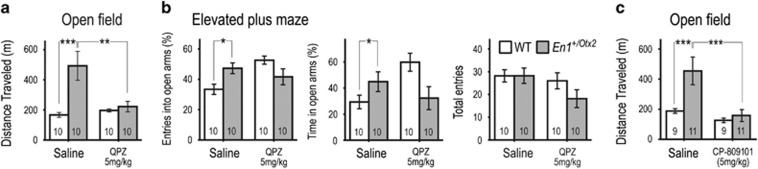

Serotonin Receptor Agonists Improve Behavioral Alterations of En1+/Otx2 Mutants

Next, we sought to study the mechanisms underlying the altered behavior of En1+/Otx2 mutants. Given the decreased serotonin levels in En1+/Otx2 mutants in all investigated brain areas (Brodski et al, 2003; Tilleman et al, 2009), we hypothesized that reduced serotonin has a critical role in behavioral alterations of En1+/Otx2 mutants.

Acute treatment with the mixed serotonin receptor agonist quipazine selectively reduced the distance mutants traveled in the OFT (Figure 4a). There was a significant interaction between genotype and quipazine treatment in the percentages of entries and time animals spent in the open arms of the EPM (Figure 4b). Quipazine did not significantly affect number of entries into all arms of the apparatus (Figure 4b). On the basis of the receptor profile of quipazine (Friedman et al, 1984) and the role of 5-HT2C receptors in repressing DA activity (Di Matteo et al, 2000), we hypothesized that the 5-HT2C receptor mediates the quipazine effect. Indeed, the selective 5-HT2C agonist CP-809101 reduced hyperactivity in En1+/Otx2 mutants in the OFT (Figure 4c). We conclude that the reduction of serotonin receptor activation in En1+/Otx2 mutants, specifically of 5-HT2C receptors, is critically involved in the hyperactivity and anxiety-like behavior observed in these animals.

Figure 4.

Quipazine and CP-809101 reduce hyperactivity of En1+/Otx2 mutants in the open field. Animals were tested 15 min after IP injection of saline, 5 mg/kg quipazine, or 5 mg/kg CP-809101. (a) Quipazine specifically decreased distance traveled in the OFT for mutants (Genotype*TreatmentF1,36=8.429, p=0.006; Fisher's LSD post hoc test, p=0.001). (b) There was a significant interaction between genotype and quipazine treatment in percentages of entries into (Genotype*TreatmentF1,36=11.534, p=0.002) and the time spent in the open arms of the EPM (Genotype*TreatmentF1,36=9.286, p=0.005), with no such interaction in the number of entries into all arms (Genotype*TreatmentF1,36=1.352, p=0.254). (c) The selective 5-HT2C agonist CP-809101 reduced hyperactivity in En1+/Otx2 mutants in the OFT (Genotype*TreatmentF1,36=4.249, p=0.047; Fisher's LSD post hoc test, p<0.001). Fisher's LSD post hoc test: *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

Sequence Variants in Genes Controlling the Development of DA and 5-HT Neurons are Associated with BPD

To study the relevance of our findings for BPD in humans, we tested the hypothesis that variants in genes directing specification of monoaminergic neurons are associated with BPD. To this end, we employed INRICH, a pathway-based genome-wide association analysis tool that tests for enriched association signals of predefined gene sets across independent genomic intervals (Lee et al, 2012).

Initially, we compiled two lists, containing genes controlling the specification of DA and 5-HT neurons, respectively. Genes were included in the lists when a gain- or loss-of-function mutation in mammals leads to a change in the specification of midbrain DA or rostral hindbrain 5-HT neurons in vivo (see Supplementary Methods for further details). Using INRICH, both DA and 5-HT specification pathways showed a significant global enrichment for BPD. For the DA pathway, 10 out of 34 genes were in associated intervals and for the 5 HT pathway 4 out of 19 genes (Table 1).

Table 1. Association between Polymorphisms of the Genes Specifying DA and 5-HT Neurons and Psychiatric Disorders.

| Gene List | Number of genes | Pval. BPD | Pval. SCZ | Pval. MDD |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dopaminergic specification | ||||

| BDNF (Baquet et al, 2005), CDH2 (Sakane and Miyamoto, 2013), CTNNB1 (Tang et al, 2010), DKK1 (Ribeiro et al, 2011), EGFR (Iwakura et al, 2011), EN1 (Alberi et al, 2004; Alves dos Santos and Smidt, 2011; Ellisor et al, 2012; Simon et al, 2001), EN2 (Ellisor et al, 2012; Simon et al, 2001), FERD3L (Ono et al, 2010), FGF2 (Ratzka et al, 2012), FGFR1 (Lahti et al, 2012), FGFR2 (Lahti et al, 2012), FOXA1 (Ferri et al, 2007), FOXA2 (Ferri et al, 2007; Hynes et al, 1995), GDNF (Kholodilov et al, 2004), GLI1 (Hynes et al, 1997), GLI2 (Matise et al, 1998a), LMX1A (Andersson et al, 2006b; Deng et al, 2011), LMX1B (Deng et al, 2011; Smidt et al, 2000), MSX1 (Andersson et al, 2006b), NEUROG2 (Andersson et al, 2006a; Kele et al, 2006), NR4A2 (Zetterstrom et al, 1997), ONECUT1 (Chakrabarty et al, 2012), ONECUT2 (Chakrabarty et al, 2012), OTX2 (Brodski et al, 2003; Omodei et al, 2008), PHOX2B (Deng et al, 2011; Hoekstra et al, 2012), PITX3 (Smidt et al, 2004), RSPO1 (Hoekstra et al, 2013), SHH (Joksimovic et al, 2009), SMO (Hynes et al, 2000a), TGFA (Blum, 1998), UNCX (Rabe et al, 2012), WNT1 (Alves dos Santos and Smidt, 2011; Ellisor et al, 2012; Prakash et al, 2006), WNT2 (Sousa et al, 2010), WNT5A (Andersson et al, 2008) | 34 | 0.011 0.033a | 1 | 1 |

| Dopaminergic specification (Hegarty et al, 2013) | ||||

| CTNNB1, DKK1, EN1, EN2, FERD3L, FGF2, FGFR1, FOXA2, FZD3, FZD6, GLI1, GLI2, HES1, LMX1A, LMX1B, LRP6, NEUROG2, NR4A2, ONECUT1, ONECUT2, OTX2, PAX2, PAX5, PITX3, WNT1, WNT2 | 26 | 0.025 0.042a | 1 | 1 |

| Serotonergic specification | ||||

| ASCL1 (Pattyn et al, 2004), EN1 (Fox and Deneris, 2012; Simon et al, 2005), EN2 (Fox and Deneris, 2012), FOXA2 (Jacob et al, 2007), GATA2 (Craven et al, 2004), GATA3 (van Doorninck et al, 1999), GLI1 (Hynes et al, 1997), GLI2 (Matise et al, 1998b), INSM1 (Jacob et al, 2009), LMX1B (Ding et al, 2003), STXBP1 (Dudok et al, 2011), NKX2-2 (Briscoe et al, 1999), OTX2 (Brodski et al, 2003), FEV (Hendricks et al, 2003), PHOX2B (Pattyn et al, 2003), SIM1 (Osterberg et al, 2011), SHH (Hynes et al, 1997), SMO (Hynes et al, 2000b), WNT1 (Simon et al, 2005) | 19 | 0.028 | 1 | 1 |

FDR corrected p-values; Abbreviations: MDD, major depressive disorder; SCZ, schizophrenia. For the references see the supplement.

Recently, a list compiling all mouse mutants showing alterations in the development of DA neurons has been reported (Hegarty et al, 2013). To further validate our findings, we used the list of genes mutated in these animals for INRICH analysis. We found that genes controlling the specification of DA neurons showed significant global enrichment (Table 1). In contrast, the global enrichment for all genes affecting DA development, including migration and projection, did not show significant association (p=0.177). Global enrichment values stayed significant after FDR correction for multiple testing for our compiled DA specification list and for the lists based on the publication by Hegarty et al (Table 1).

Finally, we tested genes directing the specification of DA and 5-HT neurons to determine if they are associated with schizophrenia and major depressive disorder. Global enrichment with these disorders was not observed (Table 1). Taken together, our findings indicate that common DNA variants within genes controlling the specification of DA and 5-HT neurons are associated with BPD in humans.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we report that mutants exhibiting alterations in the specification of monoaminergic neurons show endogenous fluctuations of manic- and depressive-like behaviors. Drugs used for the treatment of BPD, as well as serotonin receptor agonists, ameliorate the behavioral alterations in these animals. In addition, we provide evidence that a linkage disequilibrium-independent genomic enrichment analysis yields an association of BPD with aggregates of genes directing the specification of monoaminergic neurons. In summary, our data indicate that aberrations in the genetic pathways regulating specification of DA and 5-HT neurons lead to mood instability. Our results further suggest that genetic variants in these pathways are associated with BPD in humans.

Validity and Limitations of En1+/Otx2 Mutants as Model for Mood Fluctuations and BPD

The molecular underpinnings of spontaneous mood fluctuations are virtually unknown, in large part due to the lack of suitable animal models. We now propose En1+/Otx2 mutants as a model for this behavior and offer evidence that it can be caused by a neurodevelopmental aberration. Behavioral fluctuations observed in BPD are challenging to model in animals, and current paradigms emulate limited aspects of this disorder (Chen et al, 2010; Gould and Einat, 2007; Kara and Einat, 2013; Nestler and Hyman, 2010). Although En1+/Otx2 mutants do not mimic all aspects of BPD, they represent a significant advancement toward more valid BPD models. In the following, we discuss validity and limitations of En1+/Otx2 mutants as a BPD model.

Face validity

Mutants show manic- and depressive-like behavior. The former as indicated by increased locomotor activity and risk-taking behavior, and the latter as indicated by the reduced hedonic-like behavior. Significantly, mutants show also increased fluctuations in these behaviors. For the interpretation of the results, it is important to address whether increased variability could be confounded by differences in the absolute measures. Different results suggest that this is not the case. For both mutants and controls, the levels of locomotor activity are not correlated with the levels of fluctuations in the open field. Moreover, mutants and controls do not differ in the distance traveled in the center of the OFT, whereas the fluctuation in these parameters is increased in mutants. Finally, in the pharmacological experiments, changes in the fluctuations for the distance animals traveled in the center and the frequency animals entered the center did not correlate with changes in the absolute measures.

Mutants showed fluctuations in both manic- and depressive-like behavior, recapitulating aspects of a mixed state in BPD patients, defined by co-occurrence of manic and depressive symptoms (McElroy et al, 1995; Perugi et al, 2013). However, most of the mutants did not switch between manic- and depressive-like symptoms over time. One possible explanation for the low number of mutants switching between manic- and depressive-like states in the tests we used is that the time period during which we observed the animals was too short to detect a potential switch. Another possible explanation regards the experimental design of the sucrose preference test. In this paradigm, En1+/Otx2 mutants demonstrated a reduced sucrose preference. Some mutants, however, achieved the maximal sucrose preference, that is, 100%, as did most of the WT mice. Because the test does not allow assessment of sucrose preferences above the WT levels, this ‘ceiling effect' might mask periods during which mutants switch to increased hedonic-like behavior.

In contrast to BPD patients, En1+/Otx2 mutants show changes in their inferior colliculi and cerebellar vermis leading to ataxia, not correlated to their hyperactivity (Broccoli et al, 1999; Brodski et al, 2003). Although the cerebellum has been associated with manic- and depressive-like behavior (Baldacara et al, 2011; Supple et al, 1988), our pharmacological experiments suggest that the behavioral alterations of En1+/Otx2 mutants are primarily caused by dysfunctions in monoaminergic neurotransmission.

Predictive validity

Drugs used for the treatment of BPD ameliorate behavioral alterations of En1+/Otx2 mutants. Although lithium only partially improved the En1+/Otx2 phenotype, carbamazepine reversed most of the behavioral parameters observed in mutants, importantly also including hyperactivity and fluctuations in locomotor activity. Lithium has been estimated to be less effective in atypical forms of BPD, such as mixed manic state, whereas anticonvulsant mood stabilizers appear to cover a broader spectrum of BPD (Fountoulakis et al, 2012; Swann et al, 1997). This suggests that the predictive validity of En1+/Otx2 mutants is higher for atypical forms of BPD.

Construct validity

The INRICH analysis suggests an abnormal specification of both DA and 5-HT neurons in BPD. En1+/Otx2 mutants are particularly well suited to recapitulate these changes. First, the underlying mutation affects the specification of these neurons and not their migration or projection. Second, the mutation affects both transmitter populations.

Pathway Enrichment Analysis for GWAS in BPD

Many genes included in the lists compiled for the INRICH study have previously been implicated in BPD, including members of the Wnt pathway, Fgf pathway, BDNF, and EGFR (Pandey et al, 2012; Pedroso et al, 2012; Post, 2007; Sklar et al, 2008; Turner et al, 2012). Our results suggest that these genes, which serve very different biological functions and have not previously been attributed to a common pathway, are associated with BPD by way of their effect on the formation of monoaminergic neurons.

In addition, susceptibility genes for BPD, for example, Odz4, which have so far not been implicated in the generation of monoaminergic neurons, might be required for this process (Psychiatric GWAS Consortium Bipolar Disorder Working Group, 2011). Indeed, during mouse embryogenesis, expression of Odz4 strongly overlaps with Otx2 and Wnt1. In Drosophila, moreover, its ortholog regulates the expression of the Wnt1 ortholog (Zhou et al, 2003). It would be useful therefore to determine whether Odz4 has a role in the formation of monoaminergic neurons.

Molecular Mechanisms Underlying Fluctuations in Manic- and Depressive-Like Behavior in En1+/Otx2 Mutants

A mixed manic state, similar to the one observed in En1+/Otx2 mutants, has been described in mice in which the Clock gene has been reduced by shRNA, specifically in the ventral tegmental area (Mukherjee et al, 2010). Microarray experiments found hundreds of genes upregulated in this brain region, including Otx2 (Mukherjee et al, 2010). As the En1 and Otx2 promoters are active in adult DA neurons, it cannot be excluded that the overexpression of Otx2 in adult neurons of mutants contributes to the behavioral phenotype of these animals. However, as the changes in monoaminergic neurons in mutants originate during embryogenesis and persist throughout adulthood, it strongly suggests that behavioral alterations in these animals result from developmental disruptions.

Our finding that the serotonin receptor agonist quipazine reverses hyperactivity in En1+/Otx2 mutants supports the conclusion that reduction of 5-HT neurotransmission has a key role in the hyperactivity of these animals. Quipazine predominantly binds to 5-HT2 and 5-HT3 receptors (Roth and Hyde, 2000), suggesting that they mediate the effect of quipazine on En1+/Otx2 mutants. The reduction of hyperactivity of En1+/Otx2 mutants by the specific 5-HT2C receptor agonist CP-809101 indicates that this receptor subtype has a critical role in the phenotype of En1+/Otx2 mutants. This is in accordance with previous findings indicating antipsychotic activity of CP-809101 and identifying 5-HT2C receptors as a potential drug target for BPD (Siuciak et al, 2007).

It is known that DA neurons have a predominantly excitatory effect on 5-HT neurons, whereas 5-HT neurons have a mostly inhibitory effect on DA neurons (Di Giovanni et al, 2008; Guiard et al, 2008). On the basis of lesion studies, it could be expected that the loss of 5-HT neurons in En1+/Otx2 mutants would lead to increased firing activity of VTA DA neurons (Guiard et al, 2008). The increased DA activity would then activate remaining 5-HT neurons (Di Giovanni et al, 2008), which would in turn increase their inhibitory effect on DA neurons. Further study of this monoaminergic transmission balance in En1+/Otx2 mutants is expected to reveal how such feedback loops, intended to regulate monoaminergic homeostasis, underlie behavioral fluctuations observed in En1+/Otx2 mutants.

FUNDING AND DISCLOSURE

CB and MJ are co-inventors on the patent application ‘A method for evaluating a mental disorder' related to the mutants described in this report. EBB is co-inventor on the following patents: Means and methods for diagnosing predisposition for treatment emergent suicidal ideation (TESI). European patent number: 2166112. International application number: PCT/EP2009/061575; FKBP5: a novel target for antidepressant therapy. International publication number: WO 2005/054500 and Polymorphisms in ABCB1 associated with a lack of clinical response to medicaments. International application number: PCT/EP2005/005194. EBB has also received a honorarium from GlaxoSmithKline. The remaining authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Galila Agam, Ora Kofman, Haim Einat, Ze'ev Silverman, Marianne B. Muller, and Miroslav Savic for helpful discussion and critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by The National Institute for Psychobiology in Israel—Founded by the Charles E. Smith Family (grant 209-11-12 to CB), The Israeli Ministry of Health, Chief Scientist Office (grant 3-7433 to CB), and the Israeli Science Foundation (grant 1391/11 to CB).

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Neuropsychopharmacology website (http://www.nature.com/npp)

Supplementary Material

References

- Ayhan Y, Abazyan B, Nomura J, Kim R, Ladenheim B, Krasnova IN, et al. Differential effects of prenatal and postnatal expressions of mutant human DISC1 on neurobehavioral phenotypes in transgenic mice: evidence for neurodevelopmental origin of major psychiatric disorders. Mol Psychiatry. 2011;16:293–306. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldacara L, Nery-Fernandes F, Rocha M, Quarantini LC, Rocha GG, Guimaraes JL, et al. Is cerebellar volume related to bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2011;135:305–309. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.06.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaulieu JM. A role for Akt and glycogen synthase kinase-3 as integrators of dopamine and serotonin neurotransmission in mental health. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2012;37:7–16. doi: 10.1503/jpn.110011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belmaker RH. Bipolar disorder. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:476–486. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra035354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broccoli V, Boncinelli E, Wurst W. The caudal limit of Otx2 expression positions the isthmic organizer. Nature. 1999;401:164–168. doi: 10.1038/43670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodski C, Weisenhorn DM, Signore M, Sillaber I, Oesterheld M, Broccoli V, et al. Location and size of dopaminergic and serotonergic cell populations are controlled by the position of the midbrain-hindbrain organizer. J Neurosci. 2003;23:4199–4207. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-10-04199.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G, Henter ID, Manji HK. Translational research in bipolar disorder: emerging insights from genetically based models. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15:883–895. doi: 10.1038/mp.2010.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craddock N, Sklar P. Genetics of bipolar disorder. Lancet. 2013;381:1654–1662. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60855-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dao DT, Mahon PB, Cai X, Kovacsics CE, Blackwell RA, Arad M, et al. Mood disorder susceptibility gene CACNA1C modifies mood-related behaviors in mice and interacts with sex to influence behavior in mice and diagnosis in humans. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;68:801–810. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giovanni G, Di Matteo V, Pierucci M, Esposito E. Serotonin-dopamine interaction: electrophysiological evidence. Prog Brain Res. 2008;172:45–71. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)00903-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Matteo V, Di Giovanni G, Di Mascio M, Esposito E. Biochemical and electrophysiological evidence that RO 60-0175 inhibits mesolimbic dopaminergic function through serotonin(2C) receptors. Brain Res. 2000;865:85–90. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02246-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudok JJ, Groffen AJ, Toonen RF, Verhage M. Deletion of Munc18-1 in 5-HT neurons results in rapid degeneration of the 5-HT system and early postnatal lethality. PLoS One. 2011;6:e28137. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel SR, Creson TK, Hao Y, Shen Y, Maeng S, Nekrasova T, et al. The extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway contributes to the control of behavioral excitement. Mol Psychiatry. 2009;14:448–461. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaisher-Grinberg S, Einat H. Strain-specific battery of tests for domains of mania: effects of valproate, lithium and imipramine. Front Psychiatry. 2010;1:10. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2010.00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontana R, Della Torre S, Meda C, Longo A, Eva C, Maggi AC. Estrogen replacement therapy regulation of energy metabolism in female mouse hypothalamus. Endocrinology. 2014;155:2213–2221. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fountoulakis KN, Kontis D, Gonda X, Siamouli M, Yatham LN. Treatment of mixed bipolar states. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;15:1015–1026. doi: 10.1017/S1461145711001817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman RL, Barrett RJ, Sanders-Bush E. Discriminative stimulus properties of quipazine: mediation by serotonin2 binding sites. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1984;228:628–635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould TD, Einat H. Animal models of bipolar disorder and mood stabilizer efficacy: a critical need for improvement. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2007;31:825–831. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould TD, O'Donnell KC, Picchini AM, Manji HK. Strain differences in lithium attenuation of d-amphetamine-induced hyperlocomotion: a mouse model for the genetics of clinical response to lithium. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:1321–1333. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guiard BP, El Mansari M, Merali Z, Blier P. Functional interactions between dopamine, serotonin and norepinephrine neurons: an in-vivo electrophysiological study in rats with monoaminergic lesions. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2008;11:625–639. doi: 10.1017/S1461145707008383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han K, Holder JL, Jr, Schaaf CP, Lu H, Chen H, Kang H, et al. SHANK3 overexpression causes manic-like behaviour with unique pharmacogenetic properties. Nature. 2013;503:72–77. doi: 10.1038/nature12630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegarty SV, Sullivan AM, O'Keeffe GW. Midbrain dopaminergic neurons: a review of the molecular circuitry that regulates their development. Dev Biol. 2013;379:123–138. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kara NZ, Einat H. Rodent models for mania: practical approaches. Cell Tissue Res. 2013;354:191–201. doi: 10.1007/s00441-013-1594-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasahara T, Kubota M, Miyauchi T, Noda Y, Mouri A, Nabeshima T, et al. Mice with neuron-specific accumulation of mitochondrial DNA mutations show mood disorder-like phenotypes. Mol Psychiatry. 2006;11:523. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee PH, O'Dushlaine C, Thomas B, Purcell SM. INRICH: interval-based enrichment analysis for genome-wide association studies. Bioinformatics. 2012;28:1797–1799. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesch KP, Waider J. Serotonin in the modulation of neural plasticity and networks: implications for neurodevelopmental disorders. Neuron. 2012;76:175–191. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucki I, Dalvi A, Mayorga AJ. Sensitivity to the effects of pharmacologically selective antidepressants in different strains of mice. Psychopharmacology. 2001;155:315–322. doi: 10.1007/s002130100694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElroy SL, Strakowski SM, Keck PE, Jr, Tugrul KL, West SA, Lonczak HS. Differences and similarities in mixed and pure mania. Compr Psychiatry. 1995;36:187–194. doi: 10.1016/0010-440x(95)90080-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee S, Coque L, Cao JL, Kumar J, Chakravarty S, Asaithamby A, et al. Knockdown of Clock in the ventral tegmental area through RNA interference results in a mixed state of mania and depression-like behavior. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;68:503–511. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nestler EJ, Hyman SE. Animal models of neuropsychiatric disorders. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:1161–1169. doi: 10.1038/nn.2647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omodei D, Acampora D, Mancuso P, Prakash N, Di Giovannantonio LG, Wurst W, et al. Anterior-posterior graded response to Otx2 controls proliferation and differentiation of dopaminergic progenitors in the ventral mesencephalon. Development. 2008;135:3459–3470. doi: 10.1242/dev.027003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey A, Davis NA, White BC, Pajewski NM, Savitz J, Drevets WC, et al. Epistasis network centrality analysis yields pathway replication across two GWAS cohorts for bipolar disorder. Transl Psychiatry. 2012;2:e154. doi: 10.1038/tp.2012.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedroso I, Lourdusamy A, Rietschel M, Nothen MM, Cichon S, McGuffin P, et al. Common genetic variants and gene-expression changes associated with bipolar disorder are over-represented in brain signaling pathway genes. Biol Psychiatry. 2012;72:311–317. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2011.12.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perugi G, Medda P, Reis J, Rizzato S, Giorgi Mariani M, Mauri M. Clinical subtypes of severe bipolar mixed states. J Affect Disord. 2013;151:1076–1082. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post RM. Role of BDNF in bipolar and unipolar disorder: clinical and theoretical implications. J Psychiatr Res. 2007;41:979–990. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash N, Brodski C, Naserke T, Puelles E, Gogoi R, Hall A, et al. A Wnt1-regulated genetic network controls the identity and fate of midbrain-dopaminergic progenitors in vivo. Development. 2006;133:89–98. doi: 10.1242/dev.02181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psychiatric GWAS Consortium Bipolar Disorder Working Group Large-scale genome-wide association analysis of bipolar disorder identifies a new susceptibility locus near ODZ4. Nat Genet. 2011;43:977–983. doi: 10.1038/ng.943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth B, Hyde E.2000Pharmacology of 5-HT2 receptors Serotoninergic Neurons and 5-HT Receptors in the CNSBaumgarten HG, Göthert M (eds)Springer-Verlag: Berlin, Heidelberg; 367–394. [Google Scholar]

- Roybal K, Theobold D, Graham A, DiNieri JA, Russo SJ, Krishnan V, et al. Mania-like behavior induced by disruption of CLOCK. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:6406–6411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609625104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabunciyan S, Yolken R, Ragan CM, Potash JB, Nimgaonkar VL, Dickerson F, et al. Polymorphisms in the homeobox gene OTX2 may be a risk factor for bipolar disorder. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2007;144B:1083–1086. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanches M, Keshavan MS, Brambilla P, Soares JC. Neurodevelopmental basis of bipolar disorder: a critical appraisal. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2008;32:1617–1627. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2008.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaltiel G, Maeng S, Malkesman O, Pearson B, Schloesser RJ, Tragon T, et al. Evidence for the involvement of the kainate receptor subunit GluR6 (GRIK2) in mediating behavioral displays related to behavioral symptoms of mania. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13:858–872. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siuciak JA, Chapin DS, McCarthy SA, Guanowsky V, Brown J, Chiang P, et al. CP-809,101, a selective 5-HT2C agonist, shows activity in animal models of antipsychotic activity. Neuropharmacology. 2007;52:279–290. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sklar P, Smoller JW, Fan J, Ferreira MA, Perlis RH, Chambert K, et al. Whole-genome association study of bipolar disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13:558–569. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Supple WF, Jr, Cranney J, Leaton RN. Effects of lesions of the cerebellar vermis on VMH lesion-induced hyperdefensiveness, spontaneous mouse killing, and freezing in rats. Physiol Behav. 1988;42:145–153. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(88)90290-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann AC, Bowden CL, Morris D, Calabrese JR, Petty F, Small J, et al. Depression during mania. Treatment response to lithium or divalproex. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:37–42. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830130041008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilleman H, Kofman O, Nashelsky L, Livneh U, Roz N, Sillaber I, et al. Critical role of the embryonic mid-hindbrain organizer in the behavioral response to amphetamine and methylphenidate. Neuroscience. 2009;163:1012–1023. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.07.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner CA, Watson SJ, Akil H. The fibroblast growth factor family: neuromodulation of affective behavior. Neuron. 2012;76:160–174. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Li M, Bucan M. Pathway-based approaches for analysis of genomewide association studies. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:1278–1283. doi: 10.1086/522374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Q, Lu XY, Liu L, Schafer G, Shieh KR, Burke S, et al. Glucocorticoid receptor overexpression in forebrain: a mouse model of increased emotional lability. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:11851–11856. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402208101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zandi PP, Belmonte PL, Willour VL, Goes FS, Badner JA, Simpson SG, et al. Association study of Wnt signaling pathway genes in bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:785–793. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.7.785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou XH, Brandau O, Feng K, Oohashi T, Ninomiya Y, Rauch U, et al. The murine Ten-m/Odz genes show distinct but overlapping expression patterns during development and in adult brain. Gene Expr Patterns. 2003;3:397–405. doi: 10.1016/s1567-133x(03)00087-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.