Imagine a friend telling you how she recently bought a goat. Why would your friend possibly buy a goat, you wonder—or had she actually said she bought a coat? Usually, listeners spend little time deciding whether someone had talked about a goat or a coat, or a pet or a bet; instead, we instantly assign the phonemes that we are hearing to one or the other category, even though the main distinguishing feature between the phonemes /ba/ and /pa/, or /ga/ and /ka/, shows a continuous, albeit bimodal distribution. A key feature is the amount of time that passes between the plosive burst and the onset of voicing, the so-called “voice-onset-time” (VOT). For phonemes beginning with voiced stop consonants such as /ba/ and /da/, the voice sets in immediately or sometimes even shortly before the plosive sound, whereas for unvoiced stop consonants such as /pa/ and /ta/, between 20 and 100 ms may pass until voice onset. In experimental settings, English-speaking listeners assign all phonemes with a VOT up to about 35 ms to one category (e.g., /da/), whereas beyond this categorical boundary, the perception flips, and listeners assign the phoneme to the other category (in this case /ta/). This phenomenon is known as categorical perception (CP) (1) and is a crucial prerequisite for online processing and meaning attribution of the continuous speech stream. Categorical boundaries are not static, however, and depend on the linguistic community, but also the immediate linguistic information in which the phoneme in question is embedded: for instance, whether a phoneme occurs at the beginning, in the middle, or at the end of a word (2). In PNAS, Lachlan and Nowicki (3) use detailed acoustic analyses and playback experiments to show that swamp sparrows, Melospiza georgiana, categorize one specific note type depending on its position within a song syllable. With their study, they provide strong evidence that categorical perception in birds is influenced by the acoustic context in a similar fashion as in humans.

Initially, CP in the auditory domain was believed to be restricted to the perception of speech sounds by humans (4). Following a conservative definition, categorical perception could be diagnosed when the following criteria were fulfilled: (i) distinct labeling of stimulus categories (“this is a /da/”), (ii) failure to discriminate within categories, e.g., different tokens of /da/, (iii) high sensitivity to differences at the category boundary between /da/ and /ta/, for instance, and (iv) a close agreement between labeling and discrimination functions (5). More loosely, categorical perception can be conceived as a compression of within-category and/or a separation of between-category differences (6). Kuhl and Miller were the first to challenge the assumption that categorical perception in the auditory domain was restricted to human speech, by training chinchillas to discriminate between different speech tokens (7). The animals were rewarded for distinguishing between the end points of the voiced-voiceless continuum distinguishing /da/ and /ta/. In the test trials, the animals placed the phonetic boundary more or less in the middle between the two end points. However, because the animals were trained, it remained unclear whether the observed categorization was simply a result of the training and had therefore little to do with their natural categorization of sounds.

Lachlan and Nowicki built their experiments on a classic study by Nelson and Marler (8), who had investigated categorical perception in a natural learned communication system: the song of the swamp sparrow. Nelson and Marler studied the birds’ responses to variation in note duration, a feature characteristic for different populations of this species, applying the habituation-dishabituation paradigm initally used with human infants (9). With this technique, a series of stimuli is presented until the subject ceases to respond. Subsequently, a putatively distinct stimulus is broadcast. A recovery in response suggests that this stimulus is placed in a different category than those used for habituation, whereas a failure to respond to this test stimulus suggests that it is placed in the same category (10). In the original experiments, swamp sparrows from one population in New York only showed renewed responses when the note duration was switched to a length of the other category, whereas they failed to do so when the same absolute variation fell within a given category. Interestingly, in a different population of swamp sparrows in Pennsylvania, the perceptual boundary between two categories of notes differed from that found in the New York population, in accordance with the difference in the overall distribution of the different note lengths (11).

Categorical perception is not restricted to learned communication systems such as speech or bird song: by now, it has been found in such diverse taxa as crickets (12), frogs (13), and monkeys (14). Different populations of macaques differed with regard to the categorization of sounds (14), lending further support for the view that experience with the stimuli can influence the location of category boundaries, much as in human speech (15). Nonlinear responses to continuous variation in sound features thus appear to be common in a range of species. Neurobiological studies of awake swamp sparrows furthermore revealed that such categorical responses may be underpinned by single neurons, which also exhibit categorical responses in relation to changes in note duration. In these experiments, the neural response accurately mapped the learned categorical boundary typical for the local population (11). These studies suggest that birds categorically represent continuous variation in some stimulus features.

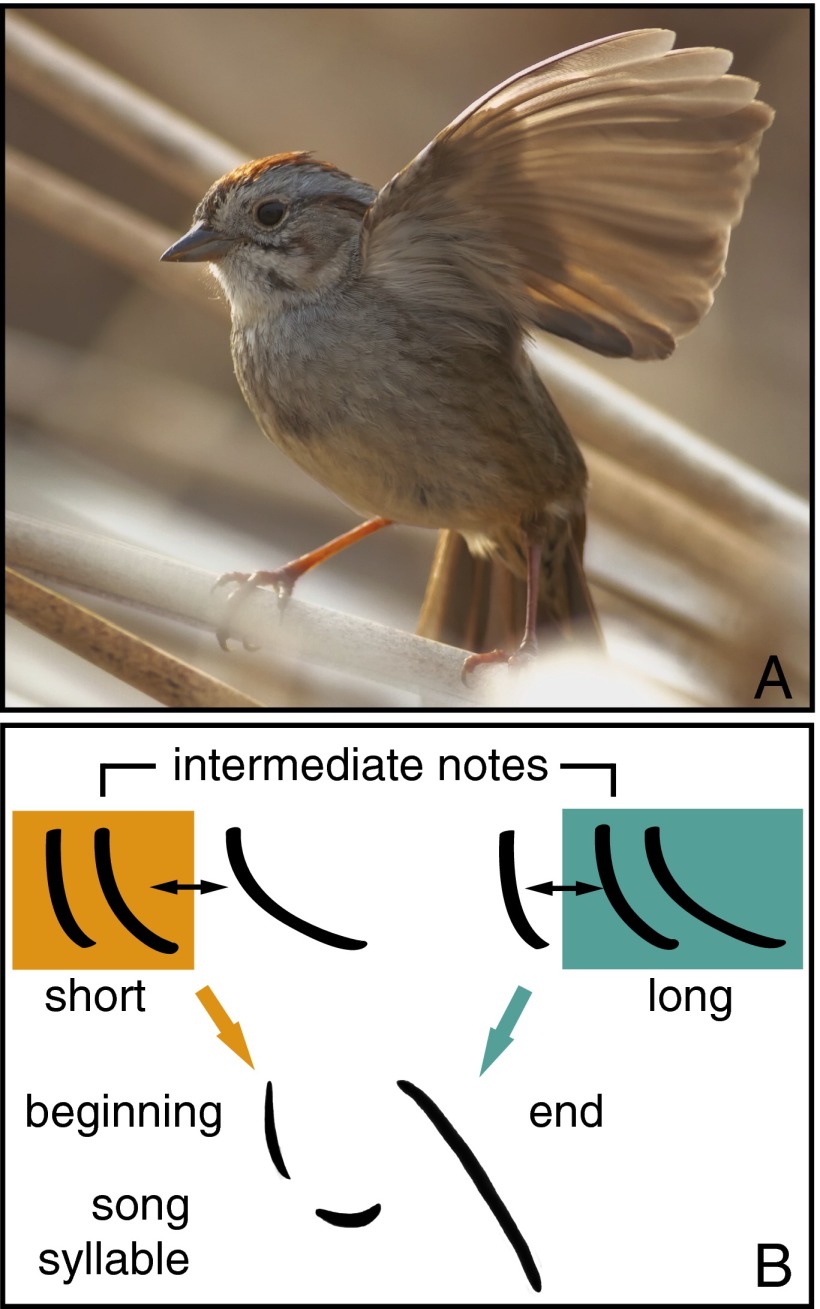

Lachlan and Nowicki now add an intriguing twist to such categorization processes by investigating whether additional information, such as the position in the syllable, may modulate the categorization of the note into one class or another (3). They first measured the characteristics of a large number of notes. The notes varied in length between about 5 and 50 ms, with three particularly frequently occurring durations, namely 9.5 (short), 17 (intermediate), and 30 ms (long). Lachlan and Nowicki then went on and tested whether the birds would distinguish between these different note lengths, using the habituation-dishabituation paradigm mentioned above. First, they presented syllables with short notes and then switched to intermediate notes (or vice versa), or they first presented intermediate notes and then switched to long ones. The birds’ responses depended on both, the switch type and the position in the syllable, in such a way that the birds ignored switches from short to intermediate notes when they occurred at the beginning of the syllable, whereas they responded strongly to the same switch when it occurred in the final position. Conversely, they responded strongly to switches from intermediate to long notes when they occurred at the beginning of the syllable, but not when they occurred in the final position. Thus, intermediate notes were grouped with short notes when in the initial position, and grouped with long notes at the final position (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

(A) Swamp sparrow, M. georgiana. Photo courtesy of Rob Lachlan (Queen Mary University of London, London, UK). (B) The birds group intermediate notes with short notes and distinguish them from long notes when they occur at the beginning of the syllable, whereas they group them with long notes when they occur at the end of the syllable. Swamp sparrow songs typically consist of multiple repetitions of a given syllable.

The study raises fundamental questions about the cognitive processes supporting these shifts in category boundaries, depending on phonological context. What remains unclear, however, is whether the birds actually perceived the intermediate notes as short or long, respectively, or whether they simply grouped them differentially. In addition, we need to understand how information about note length and syllable position are integrated. One possibility is that the

Lachlan and Nowicki use detailed acoustic analyses and playback experiments to show that swamp sparrows, Melospiza georgiana, categorize one specific note type depending on its position within a song syllable.

observed categorization can be understood as a hierarchical process, where position is noted first and then intermediate notes are assigned either to the short or long category, depending on the position in the syllable. Alternatively, the birds may just have learned that short and intermediate notes may occur at the beginning of a syllable, whereas intermediate and long notes may occur at the end of a syllable. Thus, the observed responses would be a result of a relatively simple statistical learning process. Such statistical learning may have led to the creation of perceptual anchors (16), in the sense that the birds expect to hear a short note at the beginning of the syllable and disregard minor deviation from this expectation (i.e., intermediate notes), whereas they expect to hear a long note at the end of the syllable. Either way, the study provides convincing evidence that the birds are able to take the immediate acoustic context into account when categorizing different note types.

Humans, however, do not only take into account the immediate linguistic context when assigning specific sounds to different phonemes; they also integrate other types of information, such as speaker identity or environmental information. For instance, whether you assume that your friend has bought a coat or a goat will crucially depend on the question of whether she lives on a farm in the countryside or is a renowned fashion victim. There is now increasing evidence that other animals also factor in such information. For instance, nonhuman primates take contextual variation into account when assigning ambiguous acoustic information to specific categories and when selecting differential responses (17).

In summary, the question of how the bottom-up processing of sensory information is integrated with and modulated by contextual and other higher-order information is one of the most exciting questions in communication research and socio-cognitive science more generally. Lachlan and Nowicki have added an important piece in this context by showing how sensitive even simple categorization processes are to additional information.

Footnotes

The author declares no conflict of interest.

See companion article on page 1892.

References

- 1.Fischer J. Categorical perception. In: Brown K, editor. Encyclopedia of Language & Linguistics. 2nd Ed. Elsevier; Oxford, UK: 2006. pp. 248–251. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marslen-Wilson WD, Welsh A. Processing interactions and lexical access during word recognition in continuous speech. Cognit Psychol. 1978;10(1):29–63. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lachlan RF, Nowicki S. Context-dependent categorical perception in a songbird. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:1892–1897. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1410844112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Liberman AM. Some results of research on speech perception. J Acoust Soc Am. 1957;29(1):117–123. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Studdert-Kennedy M, Liberman AM, Harris KS, Cooper FS. Theoretical notes. Motor theory of speech perception: A reply to Lane’s critical review. Psychol Rev. 1970;77(3):234–249. doi: 10.1037/h0029078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harnad S. Categorical Perception. Cambridge Univ Press; Cambridge, UK: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuhl PK, Miller JD. Speech perception by the chinchilla: voiced-voiceless distinction in alveolar plosive consonants. Science. 1975;190(4209):69–72. doi: 10.1126/science.1166301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nelson DA, Marler P. Categorical perception of a natural stimulus continuum: Birdsong. Science. 1989;244(4907):976–978. doi: 10.1126/science.2727689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eimas PD, Siqueland ER, Jusczyk P, Vigorito J. Speech perception in infants. Science. 1971;171(3968):303–306. doi: 10.1126/science.171.3968.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fischer J, Noser R, Hammerschmidt K. Bioacoustic field research: A primer to acoustic analyses and playback experiments with primates. Am J Primatol. 2013;75(7):643–663. doi: 10.1002/ajp.22153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prather JF, Nowicki S, Anderson RC, Peters S, Mooney R. Neural correlates of categorical perception in learned vocal communication. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12(2):221–228. doi: 10.1038/nn.2246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wyttenbach RA, May ML, Hoy RR. Categorical perception of sound frequency by crickets. Science. 1996;273(5281):1542–1544. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5281.1542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baugh AT, Akre KL, Ryan MJ. Categorical perception of a natural, multivariate signal: Mating call recognition in túngara frogs. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(26):8985–8988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802201105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fischer J. Barbary macaques categorize shrill barks into two call types. Anim Behav. 1998;55(4):799–807. doi: 10.1006/anbe.1997.0663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Repp BH, Liberman AM, Harnad S. Phonetic Category Boundaries Are Flexible. Categorical Perception. Cambridge Univ Press; Cambridge, UK: 1987. pp. 89–112. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iverson P, Kuhl PK. Perceptual magnet and phoneme boundary effects in speech perception: Do they arise from a common mechanism? Percept Psychophys. 2000;62(4):874–886. doi: 10.3758/bf03206929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fischer J. Information, inference and meaning in primate vocal behaviour. In: Stegmann U, editor. Animal Communication Theory: Information and Influence. Cambridge Univ Press; Cambridge: 2013. pp. 297–317. [Google Scholar]