Significance

Despite their enormous potential for diversity (in excess of 1015 theoretical receptor specificities), the human γδ T-cell repertoire is dominated by a specific subset expressing the T-cell receptor containing the γ-chain variable region 9 and the δ-chain variable region 2 (Vγ9Vδ2) known to react to a set of pathogen-derived small molecules (phosphoantigens). Overrepresentation of this restricted set of γδ T cells in adults has been thought to reflect an antigen-specific selection process resulting from postnatal exposure to pathogens. However, we demonstrate here that restricted Vγ9Vδ2 cells with preprogrammed effector function represent the predominant γδ T-cell subset circulating in human fetal blood. This observation suggests that, despite developing in a sterile environment, the human fetal γδ T cell repertoire is enriched for pathogen-reactive T cells well before pathogen exposure.

Keywords: gammadelta, human, Vγ9Vδ2, fetus, neonate

Abstract

γδ T cells are unconventional T cells recognizing antigens via their γδ T-cell receptor (TCR) in a way that is fundamentally different from conventional αβ T cells. γδ T cells usually are divided into subsets according the type of Vγ and/or Vδ chain they express in their TCR. T cells expressing the TCR containing the γ-chain variable region 9 and the δ-chain variable region 2 (Vγ9Vδ2 T cells) are the predominant γδ T-cell subset in human adult peripheral blood. The current thought is that this predominance is the result of the postnatal expansion of cells expressing particular complementary-determining region 3 (CDR3) in response to encounters with microbes, especially those generating phosphoantigens derived from the 2-C-methyl-d-erythritol 4-phosphate pathway of isoprenoid synthesis. However, here we show that, rather than requiring postnatal microbial exposure, Vγ9Vδ2 T cells are the predominant blood subset in the second-trimester fetus, whereas Vδ1+ and Vδ3+ γδ T cells are present only at low frequencies at this gestational time. Fetal blood Vγ9Vδ2 T cells are phosphoantigen responsive and display very limited diversity in the CDR3 of the Vγ9 chain gene, where a germline-encoded sequence accounts for >50% of all sequences, in association with a prototypic CDR3δ2. Furthermore, these fetal blood Vγ9Vδ2 T cells are functionally preprogrammed (e.g., IFN-γ and granzymes-A/K), with properties of rapidly activatable innatelike T cells. Thus, enrichment for phosphoantigen-responsive effector T cells has occurred within the fetus before postnatal microbial exposure. These various characteristics have been linked in the mouse to the action of selecting elements and would establish a much stronger parallel between human and murine γδ T cells than is usually articulated.

Like conventional αβ T cells and B cells, γδ T cells use V(D)J gene rearrangement with the potential to generate a set of highly diverse receptors to recognize antigens. This diversity is generated mainly in the complementary-determining region 3 (CDR3) of the T-cell antigen receptor (TCR) or B-cell antigen receptor (1–3). The tripartite subdivision of lymphocytes possessing rearranged receptors into B cells, αβ T cells, and γδ T cells has been conserved since the emergence of jawed vertebrates more than 450 Mya (1). Recently, a similar division of variable lymphocyte receptor A (VLRA)+, VLRB+, and VLRC+ cells, resembling αβ T cells, B cells, and γδ T cells, respectively, has been found in jawless vertebrates (e.g., lamprey), showing the same basic principle of lymphocyte differentiation along two distinct T-cell–like lineages and one B-cell–like lineage (4). These evolutionary data highlight the importance of both γδ T cells and αβ T cells. A major difference between αβ T cells and γδ T cells is the way they recognize antigens. In contrast to conventional αβ T cells, γδ T cells are not dependent on classical MHC molecules presenting peptides. Based on the ligands that have been identified, it appears that some γδ TCRs can recognize antigens in an antibody-like fashion, whereas the TCRs of other γδ T-cell subsets can bind to nonclassical MHC-I or MHC-like proteins (2, 5–11). Although there are common characteristics among γδ T cells, some of which are shared with VLRC+ cells (4), it is clear that γδ T cells do not represent a homogenous population of cells with a single physiological role (12). γδ T cells expressing the TCR containing the γ-chain variable region 9 and the δ-chain variable region 2 (Vγ9Vδ2 T cells) are activated by microbe- and host-derived phosphorylated prenyl metabolites (phosphorylated antigens or “phosphoantigens”) derived from the isoprenoid metabolic pathway, the most active of which are microbial (E)-4-hydroxy-3-methyl-but-2-enyl pyrophosphate (HMB-PP), produced by the 2-C-methyl-d-erythritol 4-phosphate (MEP) pathway, and host isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP) (13). These phosphoantigens recently have been shown to be presented or to be sensed by the butyrophilin BTN3A1 (14–16). Although phosphoantigen-reactive Vγ9Vδ2 T cells were thought to be restricted to primates, there is recent evidence that Vγ9, Vδ2, and BTN3A1 genes are coconserved across a variety of placental mammals including primates, alpaca, armadillo, sloth, dolphin, dromedary, and orca, but not rodents (17). The recognition of phosphoantigens allows Vγ9Vδ2 T cells to develop potent antimicrobial immune responses or to promote the killing of transformed host cells that up-regulate IPP production (18, 19). Also, treatment of cells with the aminobisphosphonate family of drugs, of which zoledronate (Zometa) is the most potent member, leads to endogenous IPP accumulation (18). This feature has been used to develop clinical trials targeting Vγ9Vδ2 T cells of patients with leukemia or solid cancers (19, 20). Vγ9Vδ2 T cells represent the main population of γδ T cells in adult human peripheral blood: About 50–90% of γδ T cells in the circulation express this combination of Vγ and Vδ chains because of postnatal expansion (21). In contrast, γδ T cells expressing the Vδ1 chain, which can pair with a variety of Vγ chains, are enriched in adult tissues such as the gut (21).

Instead of being regarded as just an immature version of the adult immune system, the immune system in early life increasingly is being recognized as different, with a bias toward the induction of a Th2 response or of immune tolerance (22–26). Indeed, one of the last cytokines to reach adult levels after birth is the Th1-promoting cytokine IL-12 (IL-12p70) (27). Originally proposed as a hypothesis by Adrian Hayday (1), there is increasing evidence, including our own results, that γδ T cells are important in early life (28–33). Although in humans circulating T cells can be detected as early as 12.5 wk gestation, most information on T cells in early life, including γδ T cells, is derived from studies on cord blood at term delivery (>37 wk gestation) (34). We hypothesized that the human fetus could produce particular fetal type of γδ T cells, as has been well established in the mouse model (35–37). Furthermore, it has been reported recently that fetal and adult hematopoietic stem cells can give rise to distinct T-cell lineages in humans, with a bias toward immune tolerance in the fetus (24).

Here we found that, unexpectedly, fetal blood around midgestation (before 30 wk) contained high levels of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells. These lymphocytes expressed a semi-invariant TCR, were phosphoantigen reactive, and showed a preprogrammed effector potential, suggesting that these γδ T cells may fulfill an important role in the immunosurveillance of fetal tissues.

Results

Human Fetal Blood Is Highly Enriched for Vγ9Vδ2 T Cells at Midgestation.

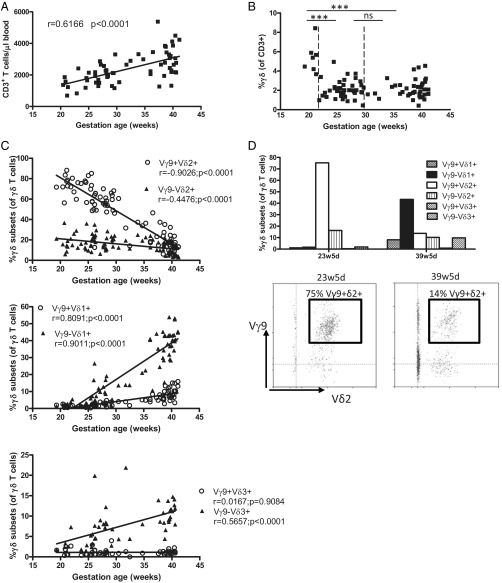

Peripheral blood from human fetuses at different time points in gestation (range 19w2d–41w1d; n = 87) (Table 1) were subjected to flow cytometric analysis to determine the absolute number of T cells per microliter of fetal blood. These numbers were relatively low (700–2,000 T cells per microliter of blood) around 20 wk gestation and increased steadily till term delivery (range 2,000–4,000 T cells per microliter of blood) (Fig. 1A). However, the contribution of γδ T cells to the total T-cell repertoire was found to be inversely correlated to gestational time, with 5.4% of T cells expressing the γδ TCR at 20 wk gestation, versus 2.2% at term delivery (Fig. 1B). To determine further whether the γδ T-cell repertoire was as diverse at these earlier gestational times as previously shown at term delivery (31, 38), flow cytometry analysis was performed with antibodies specific for Vγ9, Vδ1, Vδ2, and Vδ3. This approach allowed us to identify six γδ T-cell subpopulations in fetal peripheral blood: Vγ9+Vδ1+, Vγ9−Vδ1+, Vγ9+Vδ2+, Vγ9−Vδ2+, Vγ9+Vδ3+, and Vγ9−Vδ3+. Strikingly, and in clear contrast to term delivery, almost all (∼90–95%) γδ T cells around 20 wk gestation expressed the Vδ2 chain with Vδ1+ or Vδ3+ cells present only at marginal levels (<5% of γδ T cells) (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). Upon further examination, it became clear that the great majority (75–80%) of the γδ T cells around 20 wk gestation were Vγ9+Vδ2+ and that the second most abundant population was Vγ9−Vδ2+, which comprised ∼15–20% of γδ T cells (Fig. 1C). The percentage of Vγ9+Vδ2+ T cells gradually decreased to ∼15–20% at term delivery. The opposite was true for Vδ1+ cells, because the percentage of Vγ9−Vδ1+ cells and, to a lesser extent, of Vγ9+Vδ1+ cells increased during gestation (Fig. 1C). Vγ9−Vδ3+ cells increased as well, whereas Vγ9+Vδ3+ cells were virtually absent (Fig. 1C). For three fetuses we had the opportunity of assessing the peripheral blood composition around 20–25 wk gestation and at term delivery, confirming the presence of high numbers of Vγ9+Vδ2+ cells around 20–25 wk gestation and high levels of Vγ9−Vδ1+ lymphocytes at term delivery (Fig. 1D). Similar results were observed when the data on γδ T-cell subsets versus gestational time were expressed as absolute numbers (i.e., as the number of cells per microliter of blood) (SI Appendix, Fig. S2).

Table 1.

Gestational time and characteristics of fetuses (n = 87) included in the study

| Source of fetal blood* | Malformation | Gestational time, mean and range (n) |

| Fetal blood sampling at diagnosis | None | 24w5d, 20w3d–29w2d (13) |

| Fetal blood sampling at interruption of pregnancy | Chromosomal defect | 27w0d, 21w1d–29w4d (12) |

| Cardiovascular system | 27w6d, 22w6d–30w3d (7) | |

| Nervous system | 29w0d, 19w2d –37w2d (9) | |

| Limbs | 27w2d, 23w1d–34w5d (6) | |

| Others | 23w4d, 20w6d–32w2d (6) | |

| Umbilical cord blood at delivery | None | 39w2d, 35w2d–41w1d (37) |

Fetal blood was taken to verify possible CMV infection in fetuses whose mothers had acute CMV infection; only CMV− fetuses were included in this study. For three fetuses, samples were obtained both from fetal blood sampling at diagnosis and from umbilical cord blood at delivery.

Fig. 1.

Human fetal peripheral blood is highly enriched for the presence of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells around 20 wk gestation. (A) Absolute numbers of T cells per microliter of blood as determined by flow cytometry on fresh blood using Trucount tubes (n = 64); the linear regression line is shown together with its r and P values. (B) Percentage of γδ T cells (of CD3+ lymphocytes) according to gestational age; total n = 87; comparisons are shown between 19w2d–21w2d (n = 7), 21w5d–29w5d (n = 40), and 30w3d–41w1d (n = 40). ***P < 0.001; ns, not significant. (C) Percentages of γδ T-cell subsets of γδ+CD3+ lymphocytes according to gestational age; linear regression lines are shown with their corresponding r and P values. (D) Flow cytometry data on γδ subset percentages of γδ+CD3+ lymphocytes for one fetus from which we obtained blood both at 23w5d and at 39w5d gestation; these data are representative fo the data for three different fetuses from which blood samples were derived at two different gestational times; in the lower panel, the gate is put on γδ+CD3+ lymphocytes.

Fetal Blood CDR3γ9 Is Highly Restricted and Enriched for the Germline-Encoded Vγ9-JγP Sequence CALWEVQELGKKIKVF.

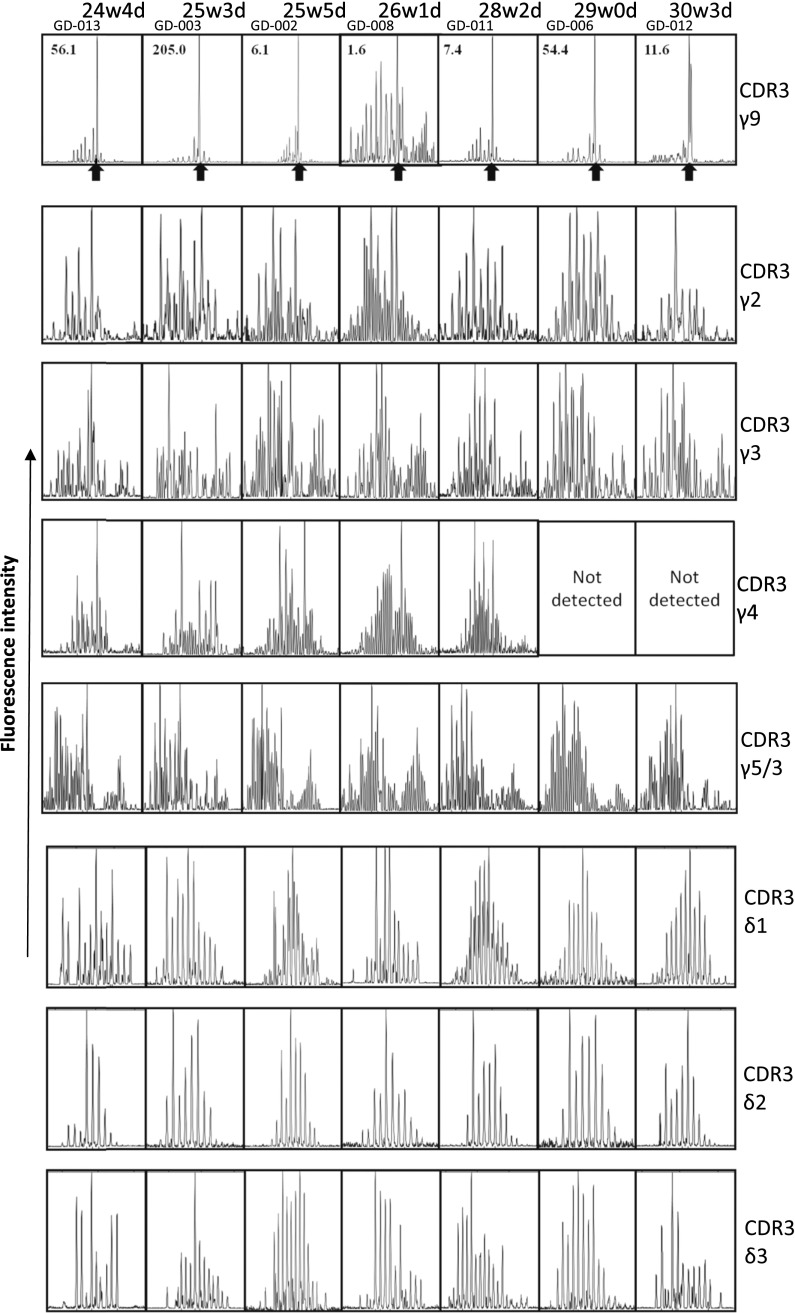

Analysis of the CDR3 repertoires of the Vδ1, Vδ2, and Vδ3 chains [constituting up to 90% of the δ chains expressed (31)] within samples of peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) derived from fetal blood at or before 30 wk gestation showed polyclonal repertoires in all seven fetuses examined (Fig. 2). Also most the CDR3γ repertoires (CDR3γ2, CDR3γ3, CDR3γ4, and CDR3γ5/3) were polyclonal. In contrast, the CDR3γ9 repertoire was highly restricted; a very high peak was observed at a CDR3γ9 length of 14 aa (Fig. 2). Sequencing of four different fetuses revealed that more than the half of the CDR3γ9 sequences corresponding to this length had exactly the same sequence: CALWEVQELGKKIKVF (71.4% for fetus GD-002; 50.0% for GD-003; 66.6% for fetus GD-006; and 55.5% for fetus GD-012) (SI Appendix, Table S2). The only other CDR3γ9 sequence we identified as being present among the sequences of all four fetuses, but at a much lower frequency, was 13 aa in length and was very similar to the highly enriched 14-aa sequence, with the loss of a single amino acid (valine) at position 5 (SI Appendix, Table S2). In contrast to the majority of the other CDR3γ9 sequences observed at 14 aa and at other lengths, these public CDR3γ9 sequences did not contain N nucleotides and thus were completely germline encoded: CALWE(V) of the Vγ9 gene segment and QELGKKIKVF of the JγP gene segment.

Fig. 2.

The CDR3γ9 repertoire of fetal blood before 30 wk gestation is highly restricted and enriched for a 14-aa length. Each box represents the spectratyping data of one fetus of the indicated CDR3 chain. The fetuses (30 wk gestation or lower) are ordered from left to right by low to high gestational age. Within the CDR3γ9 spectratyping results, the ratio of Vγ9+Vδ2+/Vγ9+Vδ2− cells is indicated for each fetus at the left top corner of the box; arrows indicate the highly enriched length of 14 aa.

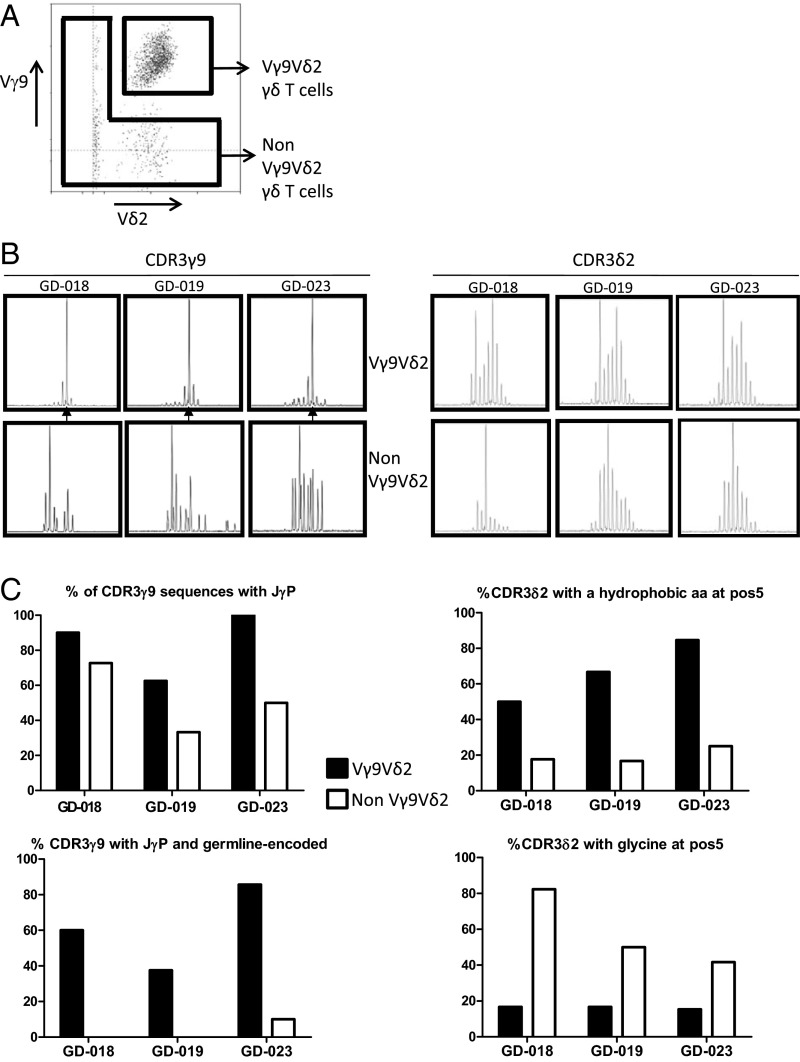

Features of the Semi-Invariant Vγ9Vδ2 TCR Are Specific for the Vγ9Vδ2 T Cells.

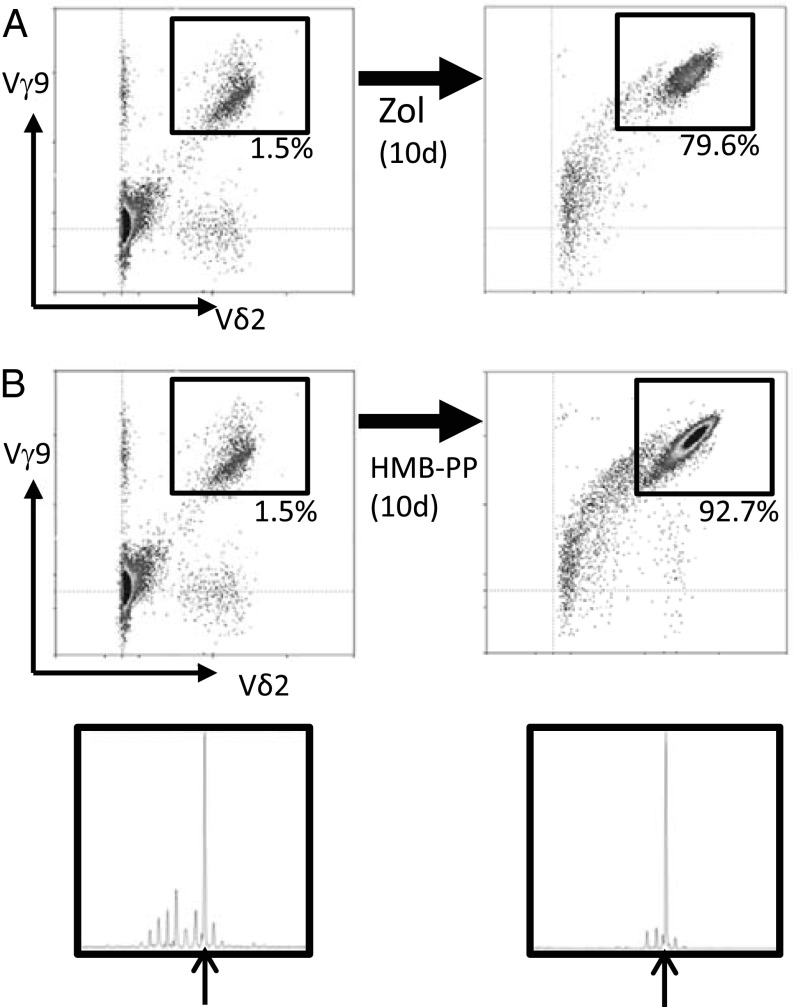

The association of the public 14-aa CDR3γ9 sequence with Vγ9Vδ2 T cells was strongly suggested by the finding that this CDR3γ9 length was underrepresented in a single atypical fetus (GD-008) in which there was conspicuously less enrichment in Vγ9Vδ2 T cells at <30 wk gestation (Fig. 2). This association was confirmed by cell sorting (Fig. 3A), which showed that the 14-aa junction length was specific for the Vγ9+Vδ2+ subset (Fig. 3B). Consistent with the enrichment of this longer CDR3γ9 was the more prevalent use of a longer J gene segment, JγP (Fig. 3C). However, the difference became striking when considering only the germline-encoded CDR3γ9 regions containing JγP: These were virtually absent from Vγ9+Vδ2− T cells (Fig. 3C and SI Appendix, Table S3). Furthermore, the public/invariant CDR3γ9 sequence CALWEVQELGKKIKVF and its low-frequency 13-aa variant could be found only within the Vγ9+Vδ2+ subset (SI Appendix, Table S3); the majority of 14-aa CDR3γ9 lengths corresponded to the public/invariant CDR3γ9 sequence (GD-018: 80.0%; GD-019: 66.6%; GD-023: 66.6%). The CDR3δ2 of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells did not show an obvious restriction in length (Fig. 3B) but was enriched in hydrophobic residues (mainly valine and tryptophan) at position 5, in contrast to the enrichment for glycine in the CDR3δ2 from Vγ9−Vδ2+ cells (Fig. 3C). Hydrophobic residues at this position have been associated with phosphoantigen reactivity (39, 40), and, as is consistent with this association, phosphoantigens were able to expand public CDR3γ9-expressing fetal Vγ9Vδ2 T cells (Fig. 4 and SI Appendix, Table S4). Both zoledronate (Fig. 4A) and HMB-PP (Fig. 4B) induced expansion of fetal Vγ9Vδ2 T cells. The expansion of fetal Vγ9Vδ2 T cells was induced by conventional concentrations of zoledronate (10 μM) in the presence of IL-2 (Fig. 4A). Maximal expansion of fetal Vγ9Vδ2 T cells was obtained with high concentrations (100 μM) of HMB-PP in the presence of IL-2 and IL-18 (SI Appendix, Fig. S3) (41). High expression of the IL-18 receptor (IL-18R) (see below) on fetal Vγ9Vδ2 T cells could contribute to this expansion and might make this subset more receptive to IL-18 in early life (27).

Fig. 3.

Fetal Vγ9Vδ2 T cells specifically possess a highly restricted germline-encoded CDR3γ9 using JγP and a conserved highly hydrophobic residue at position 5 of their CDR3δ2. (A) A typical flow cytometry plot of Vγ9 vs. Vδ2 staining on fetal blood γδ T cells (before 30 wk gestation) with gate settings illustrating the sorting strategy to sort Vγ9+Vδ2+ γδ T cells and nonVγ9Vδ2 γδ T cells; the gate is preset on CD3+γδ+ cells. (B) CDR3γ9 (Left) and CDR3δ2 (Right) showing the spectratyping plots of the sorted subsets of three different fetuses. (C) Comparison of sequence features of CDR3γ9 and CDR3δ2 in Vγ9Vδ2 versus non-Vγ9Vδ2 subsets of three fetuses.

Fig. 4.

In vitro exposure to endogenous and exogenous phosphoantigens leads to the expansion of fetal Vγ9Vδ2 T cells expressing the public/invariant CDR3γ9 CALWEVQELGKKIKVF. (A and B) Exposure of fetal PBMC to zoledronate (10 μM) in the presence of 100 U/mL IL-2 (A) and HMB-PP (100 μM) in the presence of 100 U/mL IL-2 and 50 ng/mL IL-18 (B, Upper) for 10 d. Flow cytometric staining for Vγ9 and Vδ2 ex vivo (Left) and after in vitro culture (Right); the gate is preset on CD3+ lymphocytes; numbers indicate the percentage of CD3+ lymphocytes that are Vγ9+Vδ2+. Similar results were obtained counting absolute numbers of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells. (Lower) CDR3γ9 spectratyping of fetal PBMC ex vivo and after in vitro culture with HMB-PP; arrows indicate the CDR3 length of 14 aa containing the CDR3γ9 sequence CALWEVQELGKKIKVF. Data are shown for fetus GD-011 (gestational time 28w2d) and are representative of experiments on four (A) and three (B) different fetuses.

Fetal Blood Vγ9Vδ2 T Cells Are Preprogrammed Effectors.

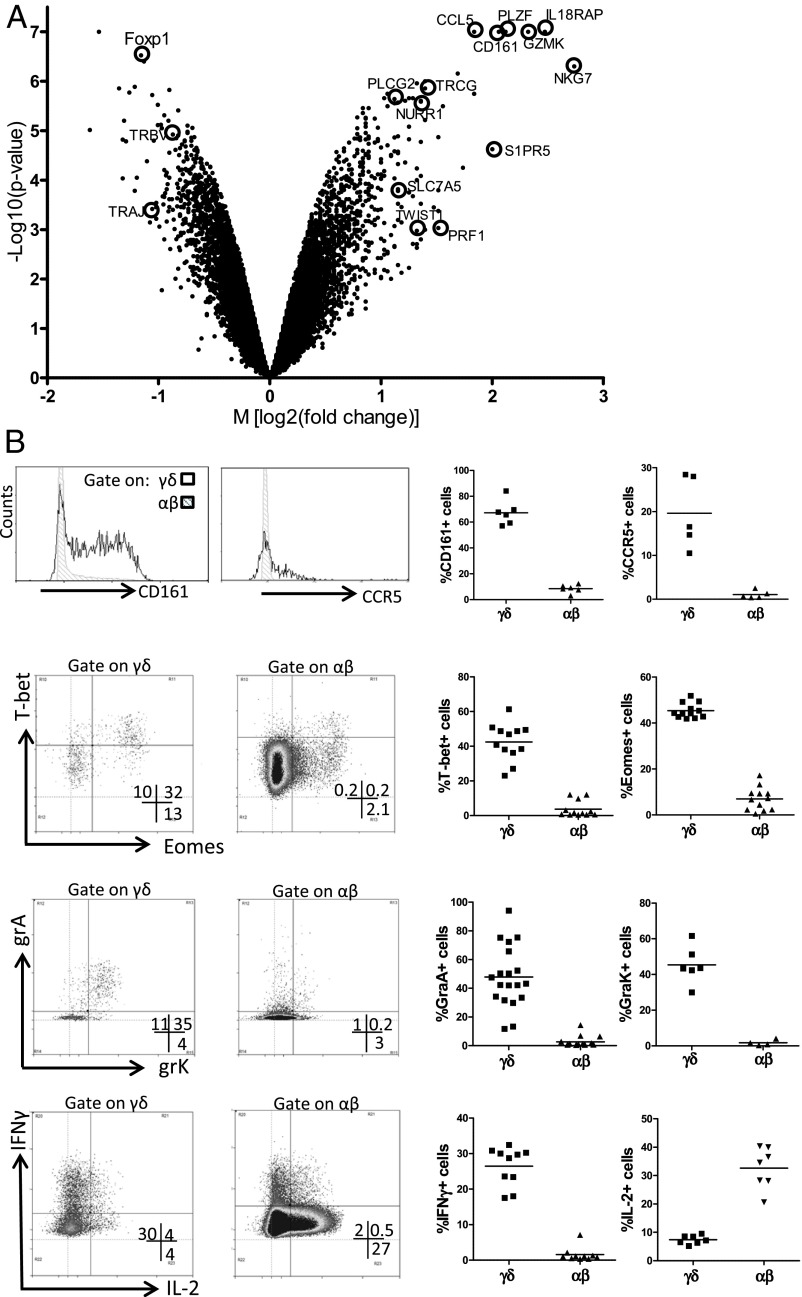

Mouse γδ T-cell subsets selected in the thymus, such as the invariant Vγ5Vδ1 subset (dendritic epidermal T cells, DETC), have been associated with a preprogrammed phenotype particularly enriched for the transcription factor T-bet and with the potential to produce IFN-γ (42–44). To determine whether the expression of the semi-invariant Vγ9Vδ2 TCR on human fetal blood Vγ9Vδ2 T cells also corresponds to such a functional preprogramming, we sorted fetal blood Vγ9Vδ2 T cells and compared their gene-expression profile with that of sorted αβ T cells from the same fetuses using whole-genome microarrays (Fig. 5A). Despite the absence of a full differentiation phenotype and lack of significant activation marker expression (SI Appendix, Table S5), this analysis of the gene-expression profile revealed a clear programming of the fetal Vγ9Vδ2 T cells toward an effector phenotype strongly biased toward the (co)expression of Th1/IFN-γ–promoting transcription factors T-bet, eomes, and Runx3 (Fig. 5B and SI Appendix, Tables S6 and S7) (45), an observation that is consistent with the specific expression of IFN-γ by fetal blood γδ T cells, at RNA and protein [detected after a brief polyclonal stimulation with phorbol12-myristate13-acetate (PMA) and ionomycin] levels (Fig. 5B and SI Appendix, Tables S5–S7). Stimulation with HMB-PP and zoledronate also induced IFN-γ expression within fetal Vγ9Vδ2 T cells, confirming their responsiveness to phosphoantigen, but to a significantly lower degree than within adult Vγ9Vδ2 T cells, as evaluated both by the percentage of IFN-γ+ cells and the amount of IFN-γ produced per cell as judged by the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of IFN-γ+ cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). High expression of other markers associated with a Th1-like status included IL-18R accessory protein (IL-18RAP; a subunit of the receptor for IL-18), nuclear receptor-related 1 (NURR1, previously associated with high IFN-γ–producing γδ T cells) (43), and Twist-related protein 1 (TWIST1), previously shown to regulate IFN-γ expression by interfering with Runx3 function (Fig. 5A) (46). In marked contrast, the expression of IL-2 protein was low in fetal γδ T cells and was enriched in αβ T cells (Fig. 5B). TNF-α showed similar RNA and protein expression in Vγ9Vδ2 T cells and αβ T cells, with a tendency (that did not reach statistical significance) to be enriched in Vγ9Vδ2 T cells (SI Appendix, Tables S5 and S7). About half of the TNF-α– and IL-2–expressing γδ T cells costained for IFN-γ. We could not detect IL-4, IL-13, or IL-17 within fetal γδ T cells (SI Appendix, Tables S5 and S7). Thus, overall, the great majority of fetal γδ T cells did not express conventional cytokines other than IFN-γ. We observed very high expression within fetal blood Vγ9Vδ2 T cells of the granzymes A and K (RNA and protein) (Fig. 5 and SI Appendix, Tables S6 and S7), showing a high degree of coexpression (Fig. 5B), but not of granzymes B, H, and M or granulysin (SI Appendix, Table S5). Perforin appeared to be enriched at the RNA level (Fig. 5A and SI Appendix, Tables S6 and S7) but did not show significant expression at protein level (SI Appendix, Table S5). Finally, the proinflammatory nature of fetal Vγ9Vδ2 T cells also was confirmed by the expression of chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 5 (CCL5) (also known as “regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and excreted,” RANTES) and the inflammatory chemokine receptors C-C chemokine receptor type 5 (CCR5) and C-X-C chemokine receptor type 3 (CXCR3), associated with a lower expression of the lymph node-homing chemokine receptor CCR7 (SI Appendix, Tables S5 and S7; MFI of CCR7 on γδ = 37.0; MFI of CCR7 on αβ = 58.5, n = 4, P = 0.0031). Also, in comparison with the small proportion of fetal γδ T cells that do not coexpress the Vγ9 and Vδ2 chain, the fetal Vγ9Vδ2 T cells expressed higher levels of T-bet, eomes, IL-18RAP, perforin, granzymes A and K, CCR5 and CXCR3 (SI Appendix, Table S8), suggesting that this preprogramming is particularly intense in fetal Vγ9Vδ2 T cells.

Fig. 5.

Fetal blood Vγ9Vδ2 T cells are preprogrammed effectors. (A) Volcano plot of genes that are differentially expressed in Vγ9Vδ2 γδ T cells and αβ T cells sorted from fetal blood (n = 4; <30 wk gestation). Each dot indicates one gene according to its M value [log2 (fold change)] and P value [log10 (P value)]. Several of the genes highly enriched within Vγ9Vδ2 γδ T cells (positive M values) and αβ T cells (negative M values) are indicated. (B) Fetal blood γδ and αβ T cells were analyzed by flow cytometry for CD161 (n = 6), the chemokine receptor CCR5 (n = 5), the transcription factors T-bet (n = 12) and eomes (n = 12), the granzymes A (n = 19) and K (n = 6), and, after 4-h stimulation with PMA/ionomycin, for the cytokines IFN-γ (n = 10) and IL-2 (n = 7). (Right) Each dot in represents the data for one fetus after gating on either γδ (CD3+γδ+ lymphocytes) or αβ (CD3+γδ− lymphocytes) T cells. (Left) Representative flow cytometry plots, after gating on either γδ or αβ T cells. Note that, because of the very high percentage of the Vγ9Vδ2 subset within γδ T cells before 30 wk gestation, results were similar when gating on total γδ+ cells or on the Vγ9+Vδ2+ subset that was specifically gated in some experiments. CCL5, RANTES; CD161, NKR-P1A, KLRB1; Foxp1, Forkhead box protein P1; GZMK, granzyme K; IL-18RAP, IL-18 receptor accessory protein; NKG7, natural killer cell group 7; NURR1, nuclear receptor-related 1; PLCG2, phospholipase C, gamma 2; PRF1, perforin; S1PR5, sphingosine-1-phosphate receptor 5; SLC7A5, a system L amino acid transporter; TWIST1, Twist-related protein 1; PLZF, promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger, ZBTB16; TRAJ, T-cell receptor α joining; TRBV, T-cell receptor β variable; TRGC, T-cell receptor γ constant.

Moreover, we found enrichment of additional genes associated with the selection of mouse invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cells, including γδ iNKT cells, which are prototypes of innate lymphocytes (47–50). Indeed, the “innate” transcription factor promyelocytic leukemia zinc finger protein (PLZF, also known as “zinc finger and BTB domain containing 16,” ZBTB16) was strikingly enriched in Vγ9Vδ2 T cells (Fig. 5A and SI Appendix, Tables S6 and S7). In line with the expression of the innate NK-T lymphocyte transcription factor PLZF, we observed high expression of a marker often used to identify these cells in human, namely, the natural killer receptor (NKR) CD161 (NKR-P1A; killer cell lectin-like receptor subfamily B member 1, KLRB1) (Fig. 5 and SI Appendix, Table S5). Members of other NKR families also showed increased expression on fetal blood γδ T cells compared with αβ T cells: natural killer group 2, member D (NKG2D), natural killer cell p30-related protein (NKp30), sphingosine 1-phosphate receptor 5 (S1PR5), killer cell lectin-like receptor subfamily G member 1 (KLRG1), PILRB, NKG2A, CD158a, and CD158b (SI Appendix, Tables S5–S7) (3, 51–53). Several adapter proteins [DNAX-activation protein 10 (DAP10), DAP12] and signaling molecules, such as phospholipase C, gamma 2 (PLCG2), PI3K, and CD3zeta, described as being associated with NKR signaling, were enriched as well (SI Appendix, Table S6) (54). Th1 bias, proinflammatory nature, and enrichment in NK genes also have been described as selective features of adult Vγ9Vδ2 T cells as compared with adult αβ T cells (55); comparison with adult Vγ9Vδ2 T-cell–enriched genes showed that indeed several also were enriched in fetal Vγ9Vδ2 T cells (SI Appendix, Table S9). Vice versa, various fetal Vγ9Vδ2 T-cell–enriched genes (such as a series of transcription factors including PLZF) but not all (e.g., DAP10 and granzyme A) also were enriched in adult Vγ9Vδ2 T cells (SI Appendix, Table S6).

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrate that effector Vγ9Vδ2 T cells with a phosphoantigen-reactive semi-invariant TCR dominate the circulating γδ T-cell repertoire in the human fetus, thus before postnatal microbial exposure.

It is accepted that the high prevalence of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells showing a restricted TCR repertoire in the adult peripheral blood is the result of extrathymic expansion of clones reacting to phosphoantigen-producing pathogens encountered after birth (21, 35, 40, 56, 57). Therefore the finding that Vγ9Vδ2 T cells are highly enriched in fetal peripheral blood (at <30 wk gestation) and display a highly restricted CDR3γ9 was unexpected. Around 20 wk gestation, at a time of low peripheral T-cell counts, γδ T cells were clearly enriched, confirming previous indications (58). Almost all γδ T cells around this gestational time expressed the Vδ2 chain, and the majority were paired with Vγ9, despite the high presence of both Vδ1 and Vδ2 chains within fetal thymi (59–61). At later gestational times the presence of Vδ2+ cells in fetal peripheral blood decreased significantly, whereas Vδ1+ cells, appearing in fetal peripheral blood around 25 wk gestation, increased continuously until they represented the major subpopulation of γδ T cells at term delivery, confirming previous observations (31, 38). We found that germline-encoded Vγ9-JγP CDR3 sequences, and CALWEVQELGKKIKVF (nucleotype tgtgccttgtgggaggtgcaagagttgggcaaaaaaatcaaggtattt) in particular, were specifically enriched in the fetal blood Vγ9Vδ2 subset. Interestingly, this sequence has been identified by high-throughput sequencing as the major sequence present among all CDR3γ sequences within adult peripheral blood samples (33, 62, 63). Furthermore, the same sequence has been found previously in fetal liver before thymic development (64). Combined with the low level or absence of the Vδ2 chain in postnatal thymi (56, 60, 61), our observations point toward a fetal wave of blood Vγ9Vδ2 production before 30 wk gestation. The decrease of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells in blood toward term delivery could be caused by sequestration in fetal tissues, in keeping with the high Vδ2 expression in fetal intestine (61). Alternatively, Vγ9Vδ2 T cells could be derived from a population of fetal stem cells, as demonstrated for mouse Vγ5Vδ1 T cells (DETC) (65), thus limiting Vγ9Vδ2 production in fetal blood to a particular time frame during gestation. After birth, exposure to environmental bacteria or food products could lead to the observed expansion of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells in the peripheral blood that persists up to adulthood (13, 56, 66).

We showed that fetal Vγ9Vδ2 T cells expressed a semi-invariant γδ TCR harboring characteristics known to be enriched in phosphoantigen-reactive TCRs (39), and we confirmed their reactivity toward endogenous phosphoantigen accumulation and to the bacterial-derived HMB-PP. The selection for phosphoantigen-reactive semi-invariant Vγ9Vδ2 T cells before postnatal microbial exposure could reflect high concentrations of endogenous phosphoantigens (such as IPP) derived from the fetal isoprenoid metabolism, HMB-PP derived from the placental microbiota (such as Escherichia coli) (13, 67), and/or a specific selecting element. Indeed, the possibility exists that one of the butyrophilin gene products may act as a selecting element, given its role in mediating stimulation by phosphoantigens and its striking homology to mouse “selection and upkeep of intraepithelial T cells protein 1” (Skint1), which so far is the only known natural selecting element for γδ T cells (5, 14–16, 44, 68, 69). Interestingly, Skint1 selects most overtly the Vγ (Vγ5) rather than the Vδ chain (affecting the Vγ5Vδ1 subset with no influence on the Vγ6Vδ1 subset possessing the same Vδ1 chain with the same CDR3δ1) (68), just as this study shows that the most overt hallmark of human fetal γδ T-cell enrichment is a conserved Vγ9-Jγ sequence.

In contrast to human postnatal γδ thymocytes (70), we showed that Vγ9Vδ2 T cells in fetal blood are clearly functionally polarized with properties of rapidly activatable innatelike T cells. Further studies will be needed to determine whether this preprogramming occurs in the fetal thymus or in the fetal peripheral tissues. Highly expressed transcription factors possibly contributing to the selective IFN-γ preprogramming within fetal blood Vγ9Vδ2 T cells are T-bet, eomes, and Runx3 (45, 71, 72). In the mouse, strong TCR engagement during their development favors the development of γδ T cells precommitted to make IFN-γ, such as DETC (42, 44 and recently reviewed in ref. 73). Thus, the precommitment of fetal blood Vγ9Vδ2 T cells to make IFN-γ could be the result of strong signaling via the above described semi-invariant Vγ9Vδ2 TCR recognizing (endogenous) phosphoantigens implicating a butyrophilin such as BTN3A1 (14, 16). A small proportion of fetal blood αβ T cells also were found to produce IFN-γ. At least part of these IFN-γ–producing fetal αβ T cells are likely to be innate T lymphocytes, including iNKT and mucosal-associated invariant T cells (69). In addition, it has been shown recently that cord blood contains a small proportion of Th1, Th2, and Th17 effector memory-like CD4+ αβ T cells, indicating the functional plasticity of this subset (74). We also showed that fetal blood Vγ9Vδ2 T cells express a particular pattern of granzymes with high coexpression of granzymes A and K but no expression of the classical killer granzyme B (75, 76). Perforin was enriched in Vγ9Vδ2 T cells at the RNA level but not at the protein level, in contrast to adult Vγ9Vδ2 T cells, which are known to express perforin, granzyme B, and granulysin protein (3). Interestingly, it has been shown recently that granzyme A produced by adult Vγ9Vδ2 T cells, independently of perforin and granzyme B, induces macrophages to inhibit the growth of intracellular mycobacteria (77). Fetal Vγ9Vδ2 T-cell effectors expressed high levels of the inflammatory chemokine receptors CCR5 and CXCR3, which have been described as being particularly highly expressed on adult blood Vγ9Vδ2 T cells (78). Thus, it seems that this feature of adult Vγ9Vδ2 T cells, like other features, such as their high capacity to produce IFN-γ and granzymes A/K, already is programmed within the fetus rather than being a consequence of exposure to phosphoantigens after birth and associated differentiation. Because of these preprogrammed effector functions, several control mechanisms probably are needed to prevent potential damage to the fetus. These mechanisms could involve inhibitory natural killer receptors such as NKG2A and KLRG1, regulation of IFN-γ expression by TWIST1, and control of granzyme A activity by cystatin 7 (also known as “cystatin F”) (46, 52, 79). In addition, in comparison with Vγ9Vδ2 T cells in adults, Vγ9Vδ2 T cells in early life appear to have a higher threshold for activation by phosphoantigens such as HMB-PP and IPP, especially for the production of cytokines (this study and refs. 29, 32, 80).

At a time when conventional effector T cells are not present, effector Vγ9Vδ2 T cells possessing a phosphoantigen-reactive semi-invariant TCR could provide protection via a lymphoid stress surveillance response (81), for example, against congenital infections with HMB-PP–producing parasites (13, 33, 82). Alternatively, the fetal Vγ9Vδ2 T-cell wave might be needed to prepare the fetus for its interaction with phosphoantigen-producing commensal bacteria after birth (13, 83) or could contribute to the formation of tissues or organs during fetal development, for example via the highly expressed granzymes A and K, which have been shown to degrade extracellular matrix proteins (75). The semi-invariant Vγ9Vδ2 TCR could serve as a target for novel vaccination strategies in early life, for which there is a clear medical need, either in utero or after birth (84, 85). Phosphoantigen-activated Vγ9Vδ2 T cells could, via their interaction with dendritic cells, promote conventional T-cell responses (86, 87) and tip the balance toward the development of a Th1 immune response in early life (74). More generally, this study sheds light on the development of an important innatelike T-cell subset that can fight infections and cancer in humans.

Methods

Study Population.

This study was approved by the Hôpital Erasme ethics committee, and all participants (mothers) gave written informed consent. We obtained blood samples (total n = 87) from the following sources: fetal blood sampling for the diagnosis CMV (only CMV− fetuses were included) (88); fetal blood sampling for interruption of pregnancy; and umbilical cord blood after delivery (Table 1). The samples were processed within 4 h. For some experiments adult blood samples were received from local routine blood donations. Mononuclear cells were obtained from blood samples by Lymphoprep gradient centrifugation (Axis-Shield).

Flow Cytometry and Cell Cultures.

The staining of fetal blood samples was done on whole blood. The following antibodies were used: CD3–PB (clone SP34-2; BD Bioscience), CD3-ECD (UCHT1; Beckman Coulter), γδ-PE (11F2; BD Bioscience), γδ-FITC (11F2; BD Bioscience), Vδ1-FITC (TS1; Thermo Fisher Scientific), Vγ9-PC5 (IMMU360; Beckman Coulter), Vδ2-FITC (IMMU389; Beckman Coulter), Vδ3-FITC (P11.5B; Beckman Coulter), CD8-PC7 (SFCl21Thy2D3; Beckman Coulter), CD4-PB (RPA-T4; BD Bioscience), HLA-DR-APC-Cy7 (L243; BD Bioscience), CD27-PE (M-T271; BD Bioscience),CD28-ECD (CD28.2; Beckman Coulter), CD45RA-PC7 (L48; BD Bioscience), CD45RO-ECD (UCHL1; Beckman Coulter), CD94-APC (HP-3D9; BD Bioscience), CD158a-FITC (HP-3E4; BD Bioscience), CD158b-FITC (CH-L; BD Bioscience), CD161-PE (DX12; BD Bioscience), NKG2D-PE (1D11; BD Bioscience), NKG2D-APC (1D11; BD Bioscience), NKG2A-PE (Z199; Beckman Coulter), NKG2C-APC (134591; R&D Systems), KLRG1-Alexa488 [clone 13F12F2, provided by H. Pircher, University of Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany] (52), perforin-FITC (δG9; BD Bioscience), granzyme A–FITC (CB9; BD Bioscience), granzyme A-PB (CB9; BioLegend), granzyme B-FITC (GB11; BD Bioscience), granzyme K-PE (24C3; ImmunoTools) (89), granulysin-Al488 (RB1; BD Bioscience), Ki-67–FITC (B56; BD Bioscience), Ki-67–PE (B56; BD Bioscience), T-bet–PE (4B10; eBioscience), T-bet–PB (4B10; BioLegend), eomes-Alexa647 (WD1928; eBioscience), IFN-γ–v450 (B27; BD Bioscience), TNFα-PC7 (Mab11; BD Bioscience), IL-17–PE (64DEC17; eBioscience), IL-2–PC7 (MQ1-17H12; BD Bioscience), CCR6-PE (FAB195P; R&D Systems), CCR5-PE (CTC5; R&D Systems), CCR7-PE (150503; R&D Systems), CCR9-PE (112509; R&D Systems). Red blood cells were lysed using FACS lysing solution (BD). The absolute numbers of CD3+, γδ T cells, and γδ T-cell subsets in whole blood were determined using Trucount beads (BD). Intracellular staining for cytotoxic molecules Ki-67, T-bet, and eomes was performed with the Perm 2 kit (BD). Fetal PBMC were cultured at 37 °C, 5% CO2 in 14-mL polypropylene, round-bottom tubes (Falcon; BD) at a final concentration of 1 ×106 cells/mL. Culture medium consisted of RPMI 1640 (Gibco, Invitrogen), supplemented with l-glutamine (2 mM), penicillin (50 U/mL), streptomycin (50 U/mL), and 1% nonessential amino acids (Lonza) and 10% (vol/vol) heat-inactivated FCS (PPA Laboratories). PMA and ionomycin were from Sigma; IL-2 (Proleukin) was from Chiron/Novartis; IL-18 was from R&D Systems; HMB-PP was from Echelon Bioscience; and zoledronate was from Novartis. For the detection of cytokines after polyclonal stimulation, PBMC (either freshly isolated or from frozen samples) were stimulated for 4 h with 10 ng/mL PMA and 2 μM ionomycin in the presence of 2 μM monensin. For detection of cytokines after phosphoantigen stimulation, PBMC were stimulated for 3 d with HMB-PP (10 nM or 100 μM) and zoledronate (10 μM) in the presence of IL-2; 4 h before the cells were harvested for flow cytometry staining, monensin (2 μM) was added to the cultures. For cytokine detection, staining was done using the Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (BD). For expansion, fetal PBMC were cultured for 10 d (with HMB-PP, zoledronate, IL-2, and IL-18 in various combinations), and the medium was changed every 3 d. After expansion culture, the cells were harvested for flow cytometry staining and for RNA extraction (spectratyping and sequencing). The absolute number of Vγ9Vδ2 T cells in culture was determined by using Ultra Rainbow beads (BD). Cells were run on the CyAn flow cytometer equipped with three lasers (405, 488, and 633 nm), and data were analyzed using Summit 4.3 (Dako). Note that, because of the very high percentage of Vγ9Vδ2 cells within the γδ T-cell subset before 30 wk gestation, results were similar with gating on total γδ+ or Vγ9+ (always included) or Vγ9+Vδ2+ (occasionally included). In the flow cytometry figures, comparisons are shown for fetal T cells before 30 wk gestation gated on γδ (CD3+γδ+ lymphocytes) versus αβ (CD3+γδ− lymphocytes).

Spectratyping and Sequencing.

Spectratyping and sequencing were performed as described previously (31); primer sequences can be found in SI Appendix, Table S1A. The CDR3 length, V gene segments, P/N nucleotides, D gene segments, and J gene segments were determined using the International ImMunoGeneTics IMGT-V-QUEST tool (www.imgt.org) (90). In the analysis of CDR3 sequences, such as the determination of the percentage of CDR3γ9 sequences containing germline-encoded JγP sequences, only in-frame sequences were taken into account. Vγ9Vδ2 γδ T cells, non-Vγ9Vδ2 γδ T cells, and αβ T cells were sorted from fetal PBMC on a FACS Aria III (BD) with more than 99% purity. RNA was isolated from 10,000–100,000 sorted T cells using the Qiagen RNeasy Microkit.

Gene-Expression Profiling.

RNA was isolated from 10,000–100,000 sorted T cells (as described above in Spectratyping and Sequencing), amplified using the Ovation PicoSL WTA System (NuGen), labeled with biotin using the Encore BiotinIL Module (NuGen), and applied on Illumina HT12 bead arrays at the GIGA-GenoTranscriptomics platform (Liège, Belgium). Microarray data have been deposited in the ArrayExpress database (accession no. E-MTAB-2669). Microarray data (derived from Affymetrix GeneChip arrays HG-U133 plus 2.0) from four adult blood Vγ9+ T-cell samples (accession no. GSE27291) and six adult blood αβ T-cell samples (accession nos. GSE15659 and GSE8059) were obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology Information Gene Expression Omnibus (55). Primers to quantify gene expression within sorted Vγ9Vδ2 γδ T cells, non-Vγ9Vδ2 γδ T cells, and αβ T cells were selected from PrimerBank (91) or were designed using Primer Express 2.0 (Applied Biosystems) (SI Appendix. Table S1B) (31). The data shown were obtained using actin as an endogenous control; similar results were obtained using cyclophilin as an endogenous control.

Statistical Analysis.

Microarray data were analyzed using BRB-ArrayTools (version 4.3.0) running under R software. Normalization was performed with the lumi package using Robust Spline Normalization, data from sorted Vγ9Vδ2 γδ T cells and αβ T cells were paired per fetus, and genes were regarded as differentially expressed when log2 change values were higher than 0.4 and P values were lower than 0.001. For flow cytometric data, comparisons between γδ and αβ T cells derived from the same fetuses were done using the two-tailed paired t test, comparisons between fetal and adult Vγ9Vδ2 T-cell activation with phosphoantigens were performed using the two-tailed unpaired t test, and comparison between different gestation age groups were done with the Kruskal–Wallis test (nonparametric ANOVA), with Dunn's multiple comparisons test, because the standard variations were different between the different groups (Instat software; GraphPad). Differences were regarded as significant at *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all the mothers who participated in this study and Hanspeter Pircher for the kind gift of KLRG1-Alexa Fluor 488 antibody. This study was supported by the Fonds National de la Recherche Scientifique (FRS-FNRS), Belgium, an Interuniversity Attraction Pole grant from the Belgian Federal Science Policy, the European Regional Development Fund, the Walloon Region, and the Fonds Gaston Ithier. The Institute for Medical Immunology is cofunded by the government of the Walloon Region and GlaxoSmithKline Biologicals. A.M. is a senior research associate of the FRS-FNRS.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. Y.-h.C. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

Data deposition: Microarray data have been deposited in the ArrayExpress database, www.ebi.ac.uk/arrayexpress (accession no. E-MTAB-2669).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1412058112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Hayday AC. [gamma][delta] cells: A right time and a right place for a conserved third way of protection. Annu Rev Immunol. 2000;18:975–1026. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chien YH, Konigshofer Y. Antigen recognition by gammadelta T cells. Immunol Rev. 2007;215:46–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2006.00470.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonneville M, O’Brien RL, Born WK. Gammadelta T cell effector functions: A blend of innate programming and acquired plasticity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10(7):467–478. doi: 10.1038/nri2781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hirano M, et al. Evolutionary implications of a third lymphocyte lineage in lampreys. Nature. 2013;501(7467):435–438. doi: 10.1038/nature12467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vantourout P, Hayday A. Six-of-the-best: Unique contributions of γδ T cells to immunology. Nat Rev Immunol. 2013;13(2):88–100. doi: 10.1038/nri3384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Willcox CR, et al. Cytomegalovirus and tumor stress surveillance by binding of a human γδ T cell antigen receptor to endothelial protein C receptor. Nat Immunol. 2012;13(9):872–879. doi: 10.1038/ni.2394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adams EJ, Chien YH, Garcia KC. Structure of a gammadelta T cell receptor in complex with the nonclassical MHC T22. Science. 2005;308(5719):227–231. doi: 10.1126/science.1106885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zeng X, et al. γδ T cells recognize a microbial encoded B cell antigen to initiate a rapid antigen-specific interleukin-17 response. Immunity. 2012;37(3):524–534. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hayday A, Vantourout P. A long-playing CD about the γδ TCR repertoire. Immunity. 2013;39(6):994–996. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luoma AM, et al. Crystal structure of Vδ1 T cell receptor in complex with CD1d-sulfatide shows MHC-like recognition of a self-lipid by human γδ T cells. Immunity. 2013;39(6):1032–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uldrich AP, et al. CD1d-lipid antigen recognition by the γδ TCR. Nat Immunol. 2013;14(11):1137–1145. doi: 10.1038/ni.2713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pang DJ, Neves JF, Sumaria N, Pennington DJ. Understanding the complexity of γδ T-cell subsets in mouse and human. Immunology. 2012;136(3):283–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2012.03582.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eberl M, et al. Microbial isoprenoid biosynthesis and human gammadelta T cell activation. FEBS Lett. 2003;544(1-3):4–10. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00483-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vavassori S, et al. Butyrophilin 3A1 binds phosphorylated antigens and stimulates human γδ T cells. Nat Immunol. 2013;14(9):908–916. doi: 10.1038/ni.2665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang H, et al. Butyrophilin 3A1 plays an essential role in prenyl pyrophosphate stimulation of human Vγ2Vδ2 T cells. J Immunol. 2013;191(3):1029–1042. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sandstrom A, et al. The intracellular B30.2 domain of butyrophilin 3A1 binds phosphoantigens to mediate activation of human Vγ9Vδ2 T cells. Immunity. 2014;40(4):490–500. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Karunakaran MM, Göbel TW, Starick L, Walter L, Herrmann T. Vγ9 and Vδ2 T cell antigen receptor genes and butyrophilin 3 (BTN3) emerged with placental mammals and are concomitantly preserved in selected species like alpaca (Vicugna pacos) Immunogenetics. 2014;66(4):243–254. doi: 10.1007/s00251-014-0763-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gober HJ, et al. Human T cell receptor gammadelta cells recognize endogenous mevalonate metabolites in tumor cells. J Exp Med. 2003;197(2):163–168. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dieli F, et al. Targeting human gammadelta T cells with zoledronate and interleukin-2 for immunotherapy of hormone-refractory prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2007;67(15):7450–7457. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilhelm M, et al. Gammadelta T cells for immune therapy of patients with lymphoid malignancies. Blood. 2003;102(1):200–206. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-12-3665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kalyan S, Kabelitz D. Defining the nature of human γδ T cells: A biographical sketch of the highly empathetic. Cell Mol Immunol. 2013;10(1):21–29. doi: 10.1038/cmi.2012.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marchant A, Goldman M. T cell-mediated immune responses in human newborns: Ready to learn? Clin Exp Immunol. 2005;141(1):10–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2005.02799.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adkins B, Leclerc C, Marshall-Clarke S. Neonatal adaptive immunity comes of age. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4(7):553–564. doi: 10.1038/nri1394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mold JE, et al. Fetal and adult hematopoietic stem cells give rise to distinct T cell lineages in humans. Science. 2010;330(6011):1695–1699. doi: 10.1126/science.1196509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang X, Yu S, Hoffmann K, Yu K, Förster R. Neonatal lymph node stromal cells drive myelodendritic lineage cells into a distinct population of CX3CR1+CD11b+F4/80+ regulatory macrophages in mice. Blood. 2012;119(17):3975–3986. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-06-359315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burt TD. Fetal regulatory T cells and peripheral immune tolerance in utero: Implications for development and disease. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2013;69(4):346–358. doi: 10.1111/aji.12083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kollmann TR, Levy O, Montgomery RR, Goriely S. Innate immune function by Toll-like receptors: Distinct responses in newborns and the elderly. Immunity. 2012;37(5):771–783. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramsburg E, Tigelaar R, Craft J, Hayday A. Age-dependent requirement for gammadelta T cells in the primary but not secondary protective immune response against an intestinal parasite. J Exp Med. 2003;198(9):1403–1414. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.De Rosa SC, et al. Ontogeny of gamma delta T cells in humans. J Immunol. 2004;172(3):1637–1645. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.3.1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gibbons DL, et al. Neonates harbour highly active gammadelta T cells with selective impairments in preterm infants. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39(7):1794–1806. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vermijlen D, et al. Human cytomegalovirus elicits fetal gammadelta T cell responses in utero. J Exp Med. 2010;207(4):807–821. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moens E, et al. IL-23R and TCR signaling drives the generation of neonatal Vgamma9Vdelta2 T cells expressing high levels of cytotoxic mediators and producing IFN-gamma and IL-17. J Leukoc Biol. 2011;89(5):743–752. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0910501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cairo C, et al. Cord blood Vγ2Vδ2 T cells provide a molecular marker for the influence of pregnancy-associated malaria on neonatal immunity. J Infect Dis. 2014;209(10):1653–1662. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lewis DB, Wilson CB. In: Infectious Disease of the Fetus and Newborn Infant. Remington JS, Klein JO, editors. Elsevier Saunders; Philadelphia: 2006. pp. 87–210. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carding SR, Egan PJ. Gammadelta T cells: Functional plasticity and heterogeneity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2(5):336–345. doi: 10.1038/nri797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shibata K. Close link between development and function of gamma-delta T cells. Microbiol Immunol. 2012;56(4):217–227. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2012.00435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prinz I, Silva-Santos B, Pennington DJ. Functional development of γδ T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2013;43(8):1988–1994. doi: 10.1002/eji.201343759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morita CT, Parker CM, Brenner MB, Band H. TCR usage and functional capabilities of human gamma delta T cells at birth. J Immunol. 1994;153(9):3979–3988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang H, Fang Z, Morita CT. Vgamma2Vdelta2 T Cell Receptor recognition of prenyl pyrophosphates is dependent on all CDRs. J Immunol. 2010;184(11):6209–6222. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davodeau F, et al. Peripheral selection of antigen receptor junctional features in a major human gamma delta subset. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23(4):804–808. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li W, et al. Effect of IL-18 on expansion of gammadelta T cells stimulated by zoledronate and IL-2. J Immunother. 2010;33(3):287–296. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181c80ffa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jensen KD, et al. Thymic selection determines gammadelta T cell effector fate: Antigen-naive cells make interleukin-17 and antigen-experienced cells make interferon gamma. Immunity. 2008;29(1):90–100. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ribot JC, et al. CD27 is a thymic determinant of the balance between interferon-gamma- and interleukin 17-producing gammadelta T cell subsets. Nat Immunol. 2009;10(4):427–436. doi: 10.1038/ni.1717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Turchinovich G, Hayday AC. Skint-1 identifies a common molecular mechanism for the development of interferon-γ-secreting versus interleukin-17-secreting γδ T cells. Immunity. 2011;35(1):59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cruz-Guilloty F, et al. Runx3 and T-box proteins cooperate to establish the transcriptional program of effector CTLs. J Exp Med. 2009;206(1):51–59. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pham D, Vincentz JW, Firulli AB, Kaplan MH. Twist1 regulates Ifng expression in Th1 cells by interfering with Runx3 function. J Immunol. 2012;189(2):832–840. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Savage AK, et al. The transcription factor PLZF directs the effector program of the NKT cell lineage. Immunity. 2008;29(3):391–403. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kreslavsky T, et al. TCR-inducible PLZF transcription factor required for innate phenotype of a subset of gammadelta T cells with restricted TCR diversity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106(30):12453–12458. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903895106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alonzo ES, Sant’Angelo DB. Development of PLZF-expressing innate T cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 2011;23(2):220–227. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pereira P, Boucontet L. Innate NKTγδ and NKTαβ cells exert similar functions and compete for a thymic niche. Eur J Immunol. 2012;42(5):1272–1281. doi: 10.1002/eji.201142109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rivera J, Proia RL, Olivera A. The alliance of sphingosine-1-phosphate and its receptors in immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8(10):753–763. doi: 10.1038/nri2400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Marcolino I, et al. Frequent expression of the natural killer cell receptor KLRG1 in human cord blood T cells: Correlation with replicative history. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34(10):2672–2680. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shiratori I, Ogasawara K, Saito T, Lanier LL, Arase H. Activation of natural killer cells and dendritic cells upon recognition of a novel CD99-like ligand by paired immunoglobulin-like type 2 receptor. J Exp Med. 2004;199(4):525–533. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gumbleton M, Kerr WG. Role of inositol phospholipid signaling in natural killer cell biology. Front Immunol. 2013;4:47. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pont F, et al. The gene expression profile of phosphoantigen-specific human γδ T lymphocytes is a blend of αβ T-cell and NK-cell signatures. Eur J Immunol. 2012;42(1):228–240. doi: 10.1002/eji.201141870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Parker CM, et al. Evidence for extrathymic changes in the T cell receptor gamma/delta repertoire. J Exp Med. 1990;171(5):1597–1612. doi: 10.1084/jem.171.5.1597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.De Libero G, et al. Selection by two powerful antigens may account for the presence of the major population of human peripheral gamma/delta T cells. J Exp Med. 1991;173(6):1311–1322. doi: 10.1084/jem.173.6.1311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Peakman M, Buggins AG, Nicolaides KH, Layton DM, Vergani D. Analysis of lymphocyte phenotypes in cord blood from early gestation fetuses. Clin Exp Immunol. 1992;90(2):345–350. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1992.tb07953.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Krangel MS, Yssel H, Brocklehurst C, Spits H. A distinct wave of human T cell receptor gamma/delta lymphocytes in the early fetal thymus: Evidence for controlled gene rearrangement and cytokine production. J Exp Med. 1990;172(3):847–859. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.3.847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.McVay LD, Carding SR, Bottomly K, Hayday AC. Regulated expression and structure of T cell receptor gamma/delta transcripts in human thymic ontogeny. EMBO J. 1991;10(1):83–91. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07923.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.McVay LD, Jaswal SS, Kennedy C, Hayday A, Carding SR. The generation of human gammadelta T cell repertoires during fetal development. J Immunol. 1998;160(12):5851–5860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Delfau MH, Hance AJ, Lecossier D, Vilmer E, Grandchamp B. Restricted diversity of V gamma 9-JP rearrangements in unstimulated human gamma/delta T lymphocytes. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22(9):2437–2443. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830220937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sherwood AM, et al. Deep sequencing of the human TCRγ and TCRβ repertoires suggests that TCRβ rearranges after αβ and γδ T cell commitment. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3(90):90ra61. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McVay LD, Carding SR. Extrathymic origin of human gamma delta T cells during fetal development. J Immunol. 1996;157(7):2873–2882. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ikuta K, et al. A developmental switch in thymic lymphocyte maturation potential occurs at the level of hematopoietic stem cells. Cell. 1990;62(5):863–874. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90262-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bukowski JF, Morita CT, Brenner MB. Human gamma delta T cells recognize alkylamines derived from microbes, edible plants, and tea: Implications for innate immunity. Immunity. 1999;11(1):57–65. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80081-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Aagaard K, et al. The placenta harbors a unique microbiome. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(237):37ra65. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Lewis JM, et al. Selection of the cutaneous intraepithelial gammadelta+ T cell repertoire by a thymic stromal determinant. Nat Immunol. 2006;7(8):843–850. doi: 10.1038/ni1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vermijlen D, Prinz I. Ontogeny of Innate T Lymphocytes - Some Innate Lymphocytes are More Innate than Others. Front Immunol. 2014;5:486. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ribot JC, Ribeiro ST, Correia DV, Sousa AE, Silva-Santos B. Human γδ thymocytes are functionally immature and differentiate into cytotoxic type 1 effector T cells upon IL-2/IL-15 signaling. J Immunol. 2014;192(5):2237–2243. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1303119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chen L, et al. Epigenetic and transcriptional programs lead to default IFN-gamma production by gammadelta T cells. J Immunol. 2007;178(5):2730–2736. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.2730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yin Z, et al. T-Bet expression and failure of GATA-3 cross-regulation lead to default production of IFN-gamma by gammadelta T cells. J Immunol. 2002;168(4):1566–1571. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.4.1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Fahl SP, Coffey F, Wiest DL. Origins of γδ T cell effector subsets: A riddle wrapped in an enigma. J Immunol. 2014;193(9):4289–4294. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1401813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zhang X, et al. CD4 T cells with effector memory phenotype and function develop in the sterile environment of the fetus. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(238):38ra72. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3008748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Anthony DA, Andrews DM, Watt SV, Trapani JA, Smyth MJ. Functional dissection of the granzyme family: Cell death and inflammation. Immunol Rev. 2010;235(1):73–92. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2010.00907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Joeckel LT, et al. Mouse granzyme K has pro-inflammatory potential. Cell Death Differ. 2011;18(7):1112–1119. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2011.5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Spencer CT, et al. Granzyme A produced by γ(9)δ(2) T cells induces human macrophages to inhibit growth of an intracellular pathogen. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9(1):e1003119. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Glatzel A, et al. Patterns of chemokine receptor expression on peripheral blood gamma delta T lymphocytes: Strong expression of CCR5 is a selective feature of V delta 2/V gamma 9 gamma delta T cells. J Immunol. 2002;168(10):4920–4929. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.10.4920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hamilton G, Colbert JD, Schuettelkopf AW, Watts C. Cystatin F is a cathepsin C-directed protease inhibitor regulated by proteolysis. EMBO J. 2008;27(3):499–508. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cairo C, et al. Vdelta2 T-lymphocyte responses in cord blood samples from Italy and Côte d’Ivoire. Immunology. 2008;124(3):380–387. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02784.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hayday AC. Gammadelta T cells and the lymphoid stress-surveillance response. Immunity. 2009;31(2):184–196. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Klein JO, Baker CJ, Remington JS, Wilson CB. In: Infectious Disease of the Fetus and Newborn Infant. Remington JS, Klein JO, editors. Elsevier Saunders; Philadelphia: 2006. pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Belkaid Y, Hand TW. Role of the microbiota in immunity and inflammation. Cell. 2014;157(1):121–141. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.PrabhuDas M, et al. Challenges in infant immunity: Implications for responses to infection and vaccines. Nat Immunol. 2011;12(3):189–194. doi: 10.1038/ni0311-189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gerdts V, Babiuk LA, Griebel PJ. van Drunen Littel-van den Hurk Fetal immunization by a DNA vaccine delivered into the oral cavity. Nat Med. 2000;6(8):929–932. doi: 10.1038/78699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ismaili J, Olislagers V, Poupot R, Fournié JJ, Goldman M. Human gamma delta T cells induce dendritic cell maturation. Clin Immunol. 2002;103(3 Pt 1):296–302. doi: 10.1006/clim.2002.5218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Fiore F, et al. Enhanced ability of dendritic cells to stimulate innate and adaptive immunity on short-term incubation with zoledronic acid. Blood. 2007;110(3):921–927. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-09-044321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Liesnard C, et al. Prenatal diagnosis of congenital cytomegalovirus infection: Prospective study of 237 pregnancies at risk. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95(6 Pt 1):881–888. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00657-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bade B, et al. Differential expression of the granzymes A, K and M and perforin in human peripheral blood lymphocytes. Int Immunol. 2005;17(11):1419–1428. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Brochet X, Lefranc MP, Giudicelli V. IMGT/V-QUEST: The highly customized and integrated system for IG and TR standardized V-J and V-D-J sequence analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(Web Server issue):W503-8. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wang X, Spandidos A, Wang H, Seed B. PrimerBank: A PCR primer database for quantitative gene expression analysis, 2012 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(Database issue):D1144–D1149. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.