Abstract

Zoning and other land-use policies are a promising but controversial strategy to improve community food environments. To understand how these policies are debated, we searched existing databases and the Internet and analyzed news coverage and legal documentation of efforts to restrict fast-food restaurants in 77 US communities in 2001 to 2013. Policies intended to improve community health were most often proposed in urban, racially diverse communities; policies proposed in small towns or majority-White communities aimed to protect community aesthetics or local businesses. Health-focused policies were subject to more criticism than other policies and were generally less successful. Our findings could inform the work of advocates interested in employing land-use policies to improve the food environment in their own communities.

In the face of rising obesity rates, public health advocates have suggested zoning and other land-use policies as a promising approach to fostering healthy food environments.1–3 Local governments can employ land-use policies to limit the number or location of businesses that sell unhealthy food, such as fast-food restaurants, or to ban these businesses outright. Policies to restrict fast food have been implemented in cities and towns across the country. Some of these policies are public health measures intended to improve community nutrition, but many restrictions on fast food have been passed to protect community aesthetics or the economy.

South Los Angeles, California, a low-income and racially diverse area of the city, implemented widely publicized restrictions on fast-food restaurants in 2008 and 2011. The area is home to a high concentration of fast-food restaurants, and the Los Angeles City Council made headlines when it banned new stand-alone fast-food restaurants in South Los Angeles as part of a health-motivated effort to encourage healthier food options.4,5 Other communities have passed fast-food land-use regulations for reasons unrelated to health with much less public fanfare or controversy. For example, Wellfleet, Massachusetts, a Cape Cod vacation destination, used the same set of legal mechanisms to ban fast-food restaurants in 2011, but its ordinance was intended to protect the town's “unique character.”6 Examining the range of ordinances to restrict fast food and how they are discussed in the news can provide important insights about the comparative success of land-use regulations intended to improve public health and regulations with other rationales.

The news media play an important role in policy debates by setting the agenda for the public and policymakers,7–10 as well as by framing the terms of debate.11,12 Journalists' decisions about which of the many pressing issues of the day to cover can raise the profile of a social issue, whereas issues outside the media spotlight can be left out of the public conversation and policymakers' consideration. Regulatory proceedings recorded in public meeting minutes and agendas are also a significant source of information about policy debates, because they provide insights into the rationale for new proposals and the policy deliberations that occur outside of the mass media.13,14

Public health is well equipped with resources on the underlying legal issues and model policy language supporting local zoning ordinances to improve food environments.1,2,15–17 Researchers have not explored how efforts to pass fast-food land-use policies have been debated under real-world circumstances, however, and this could be a vital source of data to inform similar actions.

Zoning and related policies govern the use of land in a community.1,18 Among the most common types of land-use ordinances for fast-food restaurants are total bans on the construction of new fast-food outlets and partial bans that prohibit construction of new restaurants in specific areas. Land-use ordinances may also impose moratoriums that prohibit new fast-food restaurants for a limited time. Other land-use restrictions are quotas that limit the number of restaurants that can operate in a community and regulations that specify the distance required between fast-food restaurants or between fast-food outlets and specific land uses, such as schools.1,16 Although some land-use regulations specifically restrict fast-food restaurants, policies that limit drive-throughs or formula businesses can also have the intended or unintended consequence of restricting fast-food outlets.1 Formula, or chain, businesses (characterized by a shared brand and standardized decor and services) can be fast-food restaurants such as McDonald's, but also sit-down restaurants such as Applebee's and retail outlets such as the Gap.19

We examined fast-food land-use policy debates since the advent of widespread concern about the obesity epidemic following the release of the Surgeon General's Call to Action to Prevent and Decrease Overweight and Obesity in 2001.20–23 We analyzed news coverage, legislative histories, and demographic data to understand what types of policies have been proposed, which communities have proposed them, and why. We explored the arguments used for and against these policies and how these debates and their outcomes have differed.

METHODS

To identify communities that proposed land-use policies to regulate fast food, chain businesses, or drive-through establishments from January 1, 2001, to June 1, 2013, we examined existing resources15,16 and supplemented those with Internet searches and news coverage archived in the LexisNexis database.

Data Collection

We gathered legislative history information for the proposed policies by searching each community's official Web site for meeting agendas and minutes. We also viewed the Web sites of relevant citizen-driven groups and organizations and individual blogs. The Institute for Local Self-Reliance provided valuable leads to ordinances and legislative histories in communities that passed restrictions on formula businesses and restaurants.19 These legislative histories included advocacy materials (supportive or opposing statements), community plans, council minutes and agendas, court documents, zoning bylaws, and proposed ordinances.

To establish the demographic characteristics of each community, we collected data from the 2010 Decennial Census and the 2005 to 2011 American Community Survey from the US Census Bureau Web site.24 To gather county obesity statistics, we searched the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Health Rankings Web site.25 If the communities in our sample were subdivisions of larger cities, we used census tract demographics.

To collect news coverage for each community, we conducted a keyword search in the LexisNexis news database from January 1, 2001, to June 1, 2013. We used 1 search string for all communities except for 6 that generated too many irrelevant results (Appendix A, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org, lists all key word search and sampling criteria). For example, searching for coverage of fast-food restrictions in New York City originally yielded articles on the city's restaurant trans fat ban. For these communities, we constructed a customized search string. We found 939 relevant newspaper articles and blogs and randomly selected for analysis one third of each community's coverage.

Coding

For legislative documents, 1 coder recorded the policy type, its purpose, and whether the policy passed. To determine the policy purpose for each land-use policy, we examined all legislative history documents and news coverage, in addition to ordinance language. We defined the South Los Angeles ordinance, for example, as having a nutrition-focused purpose, because nutrition was discussed in the advocacy materials and news coverage, although not in the ordinance. Each policy could have more than 1 stated rationale.

We first read a small number of news articles to develop a preliminary coding instrument and used an iterative process of coding and revising the instrument until we reached satisfactory interrater reliability for all coding measures (Krippendorff's α > 0.72; average for all measures = 0.91).26 Three coders then analyzed news articles for the policy's purpose, arguments about the policy, and the speakers associated with those arguments. For arguments, we used the sentence as the unit of analysis, and each article could contain multiple arguments.

To assess statistical differences, we conducted 2-sample proportion tests with Stata version 13.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

We identified 77 communities that proposed 100 separate fast-food–related land-use policies between January 2001 and June 2013. Our news sample included 320 articles and blogs containing 1526 arguments. We also identified 246 relevant legislative documents, including 106 ordinances, 66 meeting minutes, 37 advocacy materials, and 18 meeting agendas.

Landscape of Fast-Food Land-use Policies

The population in the 77 communities ranged from 529 (Springdale, UT) to more than 8 million (New York City), but most were fairly small: nearly 40% of the communities had fewer than 10 000 people, and 56% had fewer than 20 000 residents. More than three quarters (77%) of the communities had predominantly White residents, and 66% had average household incomes exceeding the US average.24

The policies in our sample targeted a range of businesses and used a diverse set of mechanisms (Table 1). Of the 100 land-use policies, 39 restricted chain businesses or chain restaurants. Drive-through businesses, including restaurants, were the focus of 24 policies. Another 24 policies specifically targeted fast-food restaurants. The remaining 13 policies restricted multiple types of businesses, such as an ordinance in Islamorada, Florida, that banned chain restaurants and placed restrictions on drive-through businesses.

TABLE 1—

Fast-Food Land-Use Policies by Type of Policy and Type of Business Restricted: 77 US Communities, 2001–2013

| Business | Ban or Partial Ban | Restrictions | Temporary Ban or Partial Ban | Unspecified | Total |

| Chain | 22 | 11 | 4 | 2 | 39 |

| Drive-through | 15 | 3 | 6 | 24 | |

| Fast food | 10 | 6 | 6 | 2 | 24 |

| Multiple types | 10 | 3 | 13 | ||

| Total | 57 | 23 | 16 | 4 | 100 |

Note. Sample size was n = 100.

These policies proposed 57 permanent bans, 16 temporary bans, and 23 other types of restrictions, such as conditional use and special permit requirements, quotas, and density or distance requirements. In 4 instances no specific mechanism was discussed, which we classified as unspecified restrictions (Table 1).

Of the 100 land-use policies, 68 passed and 32 did not. Of the 68 enacted policies, 5 were later repealed or overturned by the courts (Islamorada, FL; Portland, ME; San Juan Bautista, CA; Warner, NH; and Sand Point, ID).

The most common reason policies were proposed (80 instances) was to protect community aesthetics. In Port Townsend, Washington, where the city council limited formula retail and chain restaurants in the city's historic district, a resident supported the measure to avoid “compromis[ing] the integrity of our small-town charm.”27(pE1) Supporters also frequently described policies in terms of their potential to protect the local economy (61 instances) and improve quality of life (53 instances). Almost a third of policies (31 instances) were characterized as improving the walkability of the community.

Nutrition was the least frequently cited rationale for the land-use policies (20 instances). Supporters argued that zoning and other land-use restrictions could improve community nutrition and prevent obesity, diabetes, and other diet-related diseases. In San Jose, California, for example, advocates for a fast-food restaurant moratorium told the city council, “To reverse this [obesity] epidemic, we need to change our communities into places that strongly support healthy eating and active living.”28(pB1)

Influence of Nutrition in Fast-Food Land-Use Policy Debates

We found substantial differences in community demographics, policy characteristics, and patterns of news coverage when local legislators proposed policies to improve community nutrition.

Demographic and policy patterns.

Communities with more than 50% residents of color were much more likely than majority-White communities to propose land-use policies focused on improving nutrition. More than half (52%) of the policies proposed in communities of color aimed to improve health through better nutrition; only a fraction (6%) of the policies debated in predominately White communities had that goal (Z = 4.81; P < .001). Communities where land-use policies focused on nutrition were also larger and more urban: 90% of the nutrition-focused policies and only 29% of other policies were proposed in communities with populations exceeding 50 000 (Z = 7.12; P < .001).

Nutrition-focused policies mainly targeted fast-food restaurants (75% of nutrition-focused policies). Many non–nutrition-oriented policies focused more broadly on all formula businesses or restaurants (49%), with an additional 26% targeting drive-throughs.

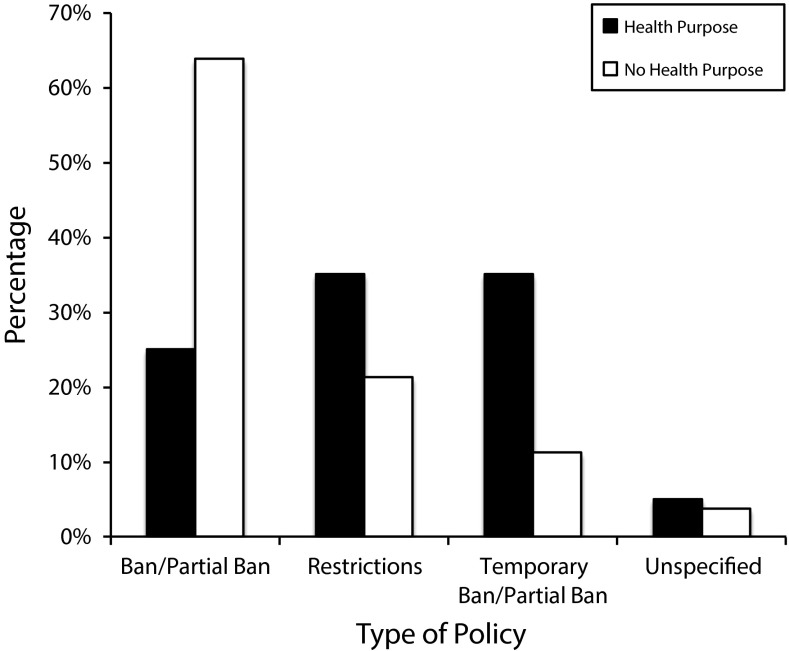

Policies without an explicit nutrition focus were often outright permanent bans on the affected businesses in either all or part of the community (Figure 1). By contrast, nutrition-focused policies tended to be temporary bans or restrictions that were less comprehensive than a full or even partial ban. Despite this, policies that focused on nutrition were less likely to pass. Only about a third (35%) of the nutrition-focused policies ultimately passed; more than three quarters (78%) of the policies that focused on non–nutrition-related benefits were implemented (Z = 3.62; P < .001).

FIGURE 1—

Percentage of fast-food land-use policies by type of policy: 77 US communities, 2001–2013.

Note. Total sample was n = 100. Totals by policy type were n = 20 for those with a health purpose and n = 80 for those without a health purpose.

Negative news coverage of nutrition-focused policies.

Overall, news coverage of nutrition-focused policies was more critical: just 41% of arguments about nutrition-focused policies supported the proposals, but a strong majority (58%) of arguments about other policies were supportive (Z = 6.73; P < .001).

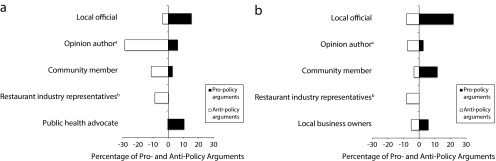

For all policies, when local officials appeared in the news they spoke overwhelmingly in support of the measures (Figure 2). However, although community residents supported non–nutrition ordinances in the news coverage, they largely opposed nutrition-focused policies. Similarly, local business owners favored non–nutrition-focused policies by a narrow margin in the news, but rarely appeared in news coverage on nutrition-driven policies. Restaurant industry representatives and opinion writers, such as columnists, overwhelmingly opposed both types of policies, but they were much more likely to comment on nutrition-focused policies.

FIGURE 2—

Most common speakers in newspaper coverage of fast-food land-use policies, by percentage of pro- and antipolicy arguments, for (a) policies with a nutrition focus and (b) policies with a non–nutrition focus: 77 US communities, 2000–2013.

Note. Total sample size was n = 1526. For policies with a nutrition focus, n = 732; for policies with a non–nutrition focus, n = 794. Arguments are presented as a percentage of total arguments for that policy type (e.g., local officials were responsible for approximately 30% of all arguments about policies with a non–nutrition focus). Speakers not shown here were: unattributed statements, other speakers, and general attributions to supporters and opponents.

aOpinion authors were columnists, editorial boards, and bloggers.

bIncludes franchises.

Supporters and opponents used very different reasoning to argue for and against the 2 different types of policies (Table 2). Although our analysis included a smaller number of nutrition-focused policies, they received a large amount of news coverage, particularly the policies proposed in South Los Angeles. As a result, the numbers of arguments (and speakers voicing those arguments) were roughly equal across nutrition-focused policies and proposals with other purposes.

TABLE 2—

Prevalence of Arguments For and Against Fast-Food Land-Use Policies in News Coverage: 77 US Communities, 2001–2013

| Nutrition Focus, % | Non–Nutrition Focus, % | Total, % | |

| Arguments in favor | |||

| Improve appearance | 3 | 53* | 33 |

| Improve health | 79 | 1* | 32 |

| Improve economy | 2 | 28* | 18 |

| Reduce community nuisance (noise, traffic, trash, etc.) | 14 | 14 | 14 |

| Improve walkability | 1 | 4* | 3 |

| Proportion of all arguments | 41 | 58 | 50 |

| Arguments against | |||

| Bad for business | 11 | 60* | 32 |

| Ineffective/unnecessary | 31 | 17* | 25 |

| Government intrusion | 37 | 8* | 24 |

| Legitimate business | 20 | 15 | 18 |

| Proportion of all arguments | 59 | 42 | 50 |

Note. Sample size was 1526 arguments in 320 news articles and blog posts. Of 765 favorable arguments, 301 focused on nutrition and 464 did not; of 761 negative arguments, 431 focused nutrition and 330 did not.

*P < .01.

Arguments in Support of Land-Use Policies

Nutrition-focused policies.

The majority (79%) of arguments in the news in support of nutrition-focused land-use restrictions contended that they were needed to improve community health through better diet, as when a member of the Pico Rivera, California, City Council, Barbara Contreras Rapisarda, remarked, “obesity is an epidemic and we need to take a stand against fast food.”29 Local officials, public health advocates, opinion writers, and community residents argued that obesity, diabetes, and other diet-related diseases were a serious problem and that zoning or other land-use policies would address the issue.

Stakeholders also advocated for policies with a nutrition rationale by emphasizing their potential to improve the quality of community life (14% of all favorable arguments) by limiting traffic and other nuisances or by making space for a diverse mix of businesses. In Baldwin Park, California, for example, a news article noted that officials decided to curb fast-food restaurants because of health concerns, but “also took into account complaints from residents about the traffic ills created by long lines of cars waiting to get into the drive-through establishments.”30

Non–nutrition-oriented policies.

By far the most common argument (53%) for regulations that did not explicitly aim to improve health was that they would protect community appearance or charm. Local officials, community members, local business owners, and opinion writers all relied heavily on this argument. A local coffee shop owner in Benicia, California, bemoaned the “onslaught” of new Starbucks stores in the town, arguing, ““Benicia has this small-town atmosphere and they're ruining it by allowing these businesses to come in.”31

Stakeholders also argued that land-use regulations would protect the local economy and local businesses (28% of all favorable arguments). Local business owners frequently used this argument, as when a bakery owner in Ogunquit, Maine, argued that formula restaurants “not only take business from other restaurants, but they hurt local suppliers, too. I sell pies to the Oarweed (restaurant) in Perkins Cove. They buy lobsters from the guys right off the boats there.”32(p1A) As with nutrition-focused policies, a vocal minority of supporters of non–nutrition-oriented policies also argued that land-use regulations would abate traffic and other community nuisances (14% of all favorable arguments).

Arguments Opposing Land-Use Policies

Nutrition-focused policies.

The most common argument that critics leveled against land-use policies intended to improve nutrition (37% of all negative arguments) was that they represented an inappropriate government intrusion into individuals' personal choices. As Detroit considered a moratorium on fast-food restaurants to improve the city's health, the Michigan Restaurant Association announced, “We don't think the answer to obesity is dictating to people what their choices will and will not be, restricting access to certain kinds of food through government fiat.”33(pA1) Opinion writers, such as bloggers, columnists, and members of editorial boards, who produced more than a third of the commentary in the news against nutrition-focused policies, most commonly employed this argument (Figure 2).

Government intrusion arguments were especially dominant in the news in South Los Angeles. Opponents of land-use measures there argued that they were paternalistic and unfairly targeted low-income residents and communities of color. Los Angeles radio host and columnist Joe Hicks accused City Councilwoman Jan Perry, the ordinance's sponsor, of “believ[ing] that the only way to save people from themselves is to have government slap food from the hands of poor black and brown residents in her district.”34(pA23) Even when they did not mention race explicitly, detractors sometimes used racially coded language about communities of color, as when Kathleen Hall of the Stress Institute argued, “We have to teach inner-city kids how to eat or they will find the less healthy foods even at the better restaurants.”35(p1)

Opponents of nutrition-focused land-use regulations also argued that the policies were the wrong approach to addressing obesity and would not improve health (31% of all negative arguments). This argument came mainly from opinion writers. A Portland Press Herald editorial about South Los Angeles' 2008 fast-food restaurant moratorium reasoned that it would not “make a serious dent” in obesity because “[u]ntil the public gets the message that overeating and a lack of exercise are deadly, the relative scarcity of restaurants will not change people's habits.”36(pA8) Critics of nutrition-focused policies, most often restaurant industry representatives or fast-food franchisees, also used the news to defend fast-food or drive-through restaurants as legitimate businesses that did not deserve regulation (20% of arguments). When Loma Linda, California, proposed restricting fast-food restaurants, McDonald's spokesperson John Lueken argued that McDonald's could offer a “contemporary dining experience and help fuel economic growth” with “options on our menu to meet a variety of dietary needs.”37(pA1)

Policy critics only occasionally used economic arguments against nutrition-focused policies (11% of all negative arguments). These critiques came mainly from the restaurant industry and opinion writers, who predicted negative impacts on businesses and low-income communities. An editorial about South Los Angeles' moratorium argued, “The city needs to increase options for food in underserved communities—not chase businesses away.”38(pC10)

Non–nutrition-oriented policies.

Opponents of policies without a nutrition focus typically argued that these measures would negatively affect the local economy by discouraging investment and entrepreneurship in the community or preventing new businesses from opening (60% of all negative arguments). This was the dominant position of all stakeholders, particularly businesspeople. The president of a local merchants' group derided a plan for formula business restrictions along the River Walk in San Antonio, Texas: “The measure might discourage investors or punish successful restaurateurs, including those that are locally based. . . . Grady's Bar B Q [is] local, but if they had one or two more stores they couldn't locate on the river.”39(p1D)

Critics of other policies also used the news to characterize land-use regulations as unnecessary or ineffective (17% of all negative arguments), maintaining that they would be difficult to enforce, were poorly designed, or would produce unintended consequences. Another 15% of opposing arguments, mostly from the restaurant industry, defended the restricted businesses as legitimate and beneficial to the community. In response to a proposal in Benicia to limit formula businesses and restaurants, a Starbucks spokesperson argued, “We work hard to weave ourselves into the fabric of the communities where we do business . . . by hiring local residents, donating volunteer time, and providing support to local non-profits and organizations.”40(pF4)

By contrast with opponents of nutrition-focused policies, people seldom criticized non–nutrition-focused policies as an inappropriate government intrusion (8% of all negative arguments). When critics evoked government overreach, it was often to characterize the measures as restricting the free market, thus violating “the most basic fundamentals of capitalism and free trade . . . the very building blocks this nation was founded upon.”41

DISCUSSION

Over the past decade, communities across the country set out to pass land-use policies to restrict fast-food restaurants. Different types of communities proposed these policies for different reasons, and we observed a clear divide between the public debates about policies focused on nutrition and those focused on other concerns. Nutrition-focused land-use policies faced more opposition, which was reflected both in newspaper coverage and in the fact that these policies were weaker (restrictions or temporary bans vs permanent bans) and less likely to have passed.

Nutrition-focused policies were most often proposed in urban, racially diverse communities where fast-food restaurants or drive-throughs already proliferated. By contrast, relatively small and affluent communities were most likely to pass land-use policies restricting fast-food restaurants to preserve community charm and historic districts or to safeguard thriving local businesses. In these small communities, community residents and the local business sector usually strongly supported land-use policies. Advocates for nutrition-driven policies, however, could not count on the support of those allies: residents and businesses alike were highly critical of land-use policies proposed for health reasons. Columnists, bloggers, and editorial boards were also much more likely to comment on nutrition-focused policies, and they were overwhelmingly critical.

Advocates hoping to use land-use restrictions to improve nutrition also faced criticisms that their proposed policies would not improve health or were nanny state policies that would allow government intrusion on individuals' choices. When nutrition-focused land-use policies were proposed in communities of color, critics of the restrictions sometimes took this line of reasoning a step further and used racially coded language or argued that the policies unfairly targeted communities of color.

Implications

Advocates looking to pass land-use policies to improve the food environment faced a challenging task. Most of the policies they proposed were never implemented, in stark contrast to policies aiming to safeguard communities' appearance or local businesses. Part of this difference can undoubtedly be attributed to the characteristics of the communities proposing the policies, but it also raises questions about how the framing of policies might affect their chances for success.

Because land-use policies focusing on improving the appearance of a community or bolstering its local businesses tend to be more successful, public health advocates promoting such policies to improve community health may want to explore the value of emphasizing these co-benefits in some cases. Framing the policy broadly in terms of community well-being, attractiveness, and economic strength, as well as improved nutrition, for example, could help to enlist residents and local business owners as allies. In addition, advocates could explore whether public support is bolstered by making the connection between improved nutrition or walkability and the economic health of the community (through, for example, a healthier workforce or more appealing commercial districts).

However, a debate about improving community appearance and walkability and protecting local businesses might play out very differently in an urban community already saturated with fast-food restaurants than in a small town with a historic downtown. For example, regardless of the rationale for the policy, when a large city that represents a valuable fast-food market proposes regulations to restrict fast-food outlets, advocates will likely face much more opposition from the restaurant industry than would those in a small town.

Our analysis raises questions about the impact of framing community policies in terms of nutrition and health. The concept of health in all policies argues that policies should be justified by their impact on health,42 but our analysis suggested that when community land-use policies were framed in terms of their potential effects on residents' eating habits, many viewed the policy as an example of government intrusion into private lives. Public health advocates should be aware that presenting policies solely as a way of changing eating patterns may elicit a strong counterframing that portrays these policies as government overreach, and they should be prepared with strategies to reframe the conversation.

Advocates should also be aware of the role of race in shaping the debate about land-use policies to improve the food environment. In our analysis we found that issues of racial equity were a major topic of news coverage in communities such as South Los Angeles. Even when race is not mentioned explicitly, racially coded language such as “inner-city youths” may cue assumptions about low-income communities of color. Advocates for land-use policies should be prepared to address explicit arguments about race, as well as unstated assumptions about which types of communities are worthy of policies that cultivate health and community well-being.

Limitations

Although newspaper coverage provides a valuable window into the public debate on fast-food land-use policies, and research suggests that, to date, newspapers set the agenda for other media,43 television, radio, or social media may also form an important part of the debate in certain communities, and our analysis did not capture these additional media outlets.

Although we made every effort to compile a comprehensive legislative history for each community, this was not possible in communities where archives were incomplete or unavailable.

Further Research

Past research has established the influence of fast-food restaurant density and unhealthy environments in general on health,44–48 but little is known about the public health impact of various types of land-use policies that could restrict fast-food restaurants. A main argument from critics of nutrition-focused land-use policies in the news was that the restrictions would not be effective at improving public health. Research is therefore needed to determine the policies' health effects.

Because land-use regulations are prospective, and generally only affect new businesses, research is also needed to assess the impact of these policies in neighborhoods already saturated with unhealthy businesses.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Healthy Eating Research program (grant 70548).

Human Participant Protection

This research did not involve human participants and thus was not subject to institutional review board approval.

References

- 1.Mair JS, Pierce MW, Teret SP. The use of zoning to restrict fast food outlets: a potential strategy to combat obesity. 2005. Available at: http://www.publichealthlaw.net/Zoning Fast Food Outlets.pdf. Accessed August 26, 2014.

- 2.Ashe M, Jernigan D, Kline R, Galaz R. Land use planning and the control of alcohol, tobacco, firearms, and fast food restaurants. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(9):1404–1408. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.9.1404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Healthy places—health food environment: zoning. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/healthyplaces/healthtopics/healthyfood/zoning.htm. Accessed April 18, 2014.

- 4.Abdollah T. A strict order for fast food. Los Angeles Times. September 9, 2007:A1. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Medina J. South Los Angeles, new fast-food spots get a “no thanks.”. New York Times. January 1, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gunlock J. Liberty-loving northeasterners... a dying breed. States News Service. April 27, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dearing JW, Rogers EM. Agenda-Setting. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gamson W. Talking Politics. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCombs M, Reynolds A. How the news shapes our civic agenda. In: Bryant J, Oliver MB, editors. Media Effects: Advances in Theory and Research. New York, NY: Taylor and Francis; 2009. pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scheufele DA, Tewksbury D. Framing, agenda setting, and priming: the evolution of three media effects models. J Commun. 2007;57(1):9–20. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Entman RM. Framing: toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. J Commun. 1993;43(4):51–58. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iyengar S. Is Anyone to Blame? How Television Frames Political Issues. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dorfman L, Cheyne A, Gottlieb MA et al. Cigarettes become a dangerous product: tobacco in the rearview mirror, 1952–1965. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(1):37–46. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kolker ES. Framing as a cultural resource in health social movements: funding activism and the breast cancer movement in the US 1990–1993. Sociol Health Illn. 2004;26(6):820–844. doi: 10.1111/j.0141-9889.2004.00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feldstein L. General plans and zoning: a toolkit for building healthy, vibrant communities. 2007. ChangeLab Solutions. Available at: http://changelabsolutions.org/publications/toolkit-gp-and-zoning. Accessed April 18, 2014.

- 16.Public Health Advocacy Institute. The zoning diet: using zoning as a potential strategy for combating local obesity. 2012. Available at: http://www.phaionline.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/07/ZoningDiet.pdf. Accessed April 18, 2014.

- 17.National Policy and Legal Analysis Network. Model healthy food zone ordinance: creating a healthy food zone around schools by regulating the location of fast food restaurants (and mobile food vendors) 2009. Available at: http://changelabsolutions.org/sites/phlpnet.org/files/nplan/HealthyFoodZone_Ordinance_FINAL_091008.pdf. Accessed April 18, 2014.

- 18. ChangeLab Solutions, National Policy and Legal Analysis Network. Licensing and zoning: tools for public health. 2012. Available at: http://changelabsolutions.org/sites/default/files/Licensing&Zoning_FINAL_20120703.pdf. Accessed May 19, 2014.

- 19.Institute for Local Self-Reliance. Formula business restrictions. Available at: http://www.ilsr.org/rule/formula-business-restrictions. Accessed April 18, 2014.

- 20.Stroup DF, Johnson V, Hahn RS, Proctor DC. Reversing the trend of childhood obesity. Prev Chronic Dis. 2009;6(3):A83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Karpyn A, Young C, Weiss S. Reestablishing healthy food retail: changing the landscape of food deserts. Child Obes. 2012;8(1):28–30. doi: 10.1089/chi.2011.0113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Consumers Union. Out of balance: marketing of soda, candy, snacks and fast foods drowns out healthful messages. 2005. Available at: http://consumersunion.org/wp-content/uploads/2005/09/OutofBalance.pdf. Accessed August 26, 2014.

- 23.Office of the Surgeon General. The Surgeon General's Call to Action to Prevent and Decrease Overweight and Obesity. Rockville, Md: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.US Census Bureau. American FactFinder—community facts. Available at: http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/community_facts.xhtml. Accessed March 28, 2014.

- 25.Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. County health rankings and roadmaps. Available at: http://www.countyhealthrankings.org. Accessed April 18, 2014.

- 26.Altheide DL. Reflections: ethnographic content analysis. Qual Sociol. 1987;10(1):65–77. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harris C. Starbucks takes its pitch to Main Street coffee chain, tells cities it can exist with mom and pop shops. Seattle Post-Intelligencer. March 28, 2007:E1. [Google Scholar]

- 28. County of Santa Clara, City of San Jose. Santa Clara County Public Health Department, City of San Jose Parks Recreation and Neighborhood Services. A health profile for the city of San Jose. Presentation to the Joint City/County/Agency Meeting, October 15, 2010. Available at: http://www.sccgov.org/sites/sccphd/en-us/Partners/Data/Documents/City%20of%20San%20Jose%20Health%20Profile%20Obesity%20Oct%2015%20final.pdf. Accessed December 2, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gonzales R. Pico Rivera continues bans on fast food places. Whittier Daily News. April 27, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wedner D. Baldwin Park, birthplace of In-N-Out Burger, bans drive-thru fast food. WalletPop [blog]. July 6, 2010. Available at: http://www.dailyfinance.com/2010/07/06/baldwin-park-birthplace-of-in-n-out-burger-bans-drive-thru-fas. Accessed January 9, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Samaniego D. Benicia considers limiting chain stores. Vallejo Times Herald. February 20, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bragg R. shrugging off chains. San Antonio Express-News. December 10, 2005:1A. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kozlowski K. Idea to bar new outlets from city stirs up heat. Detroit News. December 29, 2010:A1. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hicks J. Fast-food meddling. Los Angeles Times. July 31, 2008:A23. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wood D. Diet-conscious Los Angeles eyes moratorium on fast-food outlets. Christian Science Monitor. September 13, 2007:1. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ban on fast-food joints not the way to fight obesity problems [editorial]. Portland Press Herald. August 4, 2008:A8.

- 37.Willon P. McDonald's plan divides a health-oriented town. Los Angeles Times. January 22, 2012:A1. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Don't tell us what to eat... Chicago Tribune. August 5, 2008:C10.

- 39.Thiruvengadam M. City proposing limits on chains. San Antonio Express-News. May 20, 2006:1D. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raskin-Zrihen R. Officials look at ways to prevent Starbucks overflow. Contra Costa Times. February 9, 2007:F4. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gallagher D. McCall realtor wants to see an end to limitations on franchise businesses in McCall. Long Valley Advocate. November 11, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Public Health Institute, California Department of Public Health. Health in all policies: a guide for state and local governments. 2013. Available at: http://www.phi.org/resources/?resource=hiapguide. Accessed April 18, 2014.

- 43.Sasseen J, Olmstead K, Mitchell A. The state of the news media 2013: an annual report on American journalism. 2013. Pew Research Center's Project for Excellence in Journalism. Available at: http://stateofthemedia.org/2013/digital-as-mobile-grows-rapidly-the-pressures-on-news-intensify. Accessed January 13, 2014.

- 44.Currie J, DellaVigna S, Moretti E, Pathania V. The effect of fast food restaurants on obesity and weight gain. Am Econ J Econ Policy. 2010;2(3):32–63. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Davis B, Carpenter C. Proximity of fast-food restaurants to schools and adolescent obesity. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(3):505–510. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.137638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Reitzel LR, Regan SD, Nguyen N et al. Density and proximity of fast food restaurants and body mass index among African Americans. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(1):110–116. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carroll-Scott A, Gilstad-Hayden K, Rosenthal L et al. Disentangling neighborhood contextual associations with child body mass index, diet and physical activity: the role of built, socioeconomic, and social environments. Soc Sci Med. 2013;95:106–114. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Babey S, Wolstein J, Diamant A. Food Environments Near Home and School Related to Consumption of Soda and Fast Food. Los Angeles, CA: UCLA Center for Health Policy Research; 2011. Available at: http://healthpolicy.ucla.edu/publications/Documents/PDF/Food Environments Near Home and School Related to Consumption of Soda and Fast Food.pdf. Accessed August 26, 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]