Abstract

Objectives. We determined the prevalence of and indications for psychotropic medication among preschool children in Medicaid.

Methods. We obtained 2000 to 2003 Medicaid Analytic Extract data from 36 states. We followed children in 2 cohorts, born in 1999 and 2000, up to age 4 years. We used logistic regression to model odds of receiving medications for (1) attention-deficit disorder/attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, (2) depression or anxiety, and (3) psychotic illness or bipolar.

Results. Overall, 1.19% of children received at least 1 psychotropic drug. Medications for attention-deficit disorder/attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder treatment were most common (0.61% of all children), followed by depression or anxiety (0.59%) and psychotic illness or bipolar (0.24%). Among children, boys, those of other or unknown race compared with White, and those with other insurance compared with fee for service–only had higher odds of receiving a prescription (odds ratio [OR] = 1.80 [95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.74, 1.86], 1.87 [1.66, 1.85], and 1.14 [1.01, 1.28], respectively), whereas Black and Hispanic children had lower odds (OR = 0.51 [95% CI = 0.48, 0.53] and 0.37 [0.34, 0.39], respectively).

Conclusions. Preschoolers are receiving psychotropic medications despite limited evidence supporting safety or efficacy. Future research should focus on implementing medication use practice parameters in infant and toddler clinics, and expanding psychosocial interventions for young children with behavioral problems.

Psychotropic medication use in children has been increasing over the past several decades.1–4 It is disconcerting that there is evidence that at least part of this increase is attributable to the prescribing of psychotropic drugs among preschool children. Yet, national estimates of the magnitude of such prescribing for infants and toddlers, and the indications for such prescribing, are largely unavailable. Although there are several large, national studies of psychotropic prescribing in privately insured children,2,5 these studies make it difficult to look at prescribing specifically in very young children. For example, one study excludes children aged younger than 2 years2 and the other aggregates data from all children aged 0 to 13 years.5 There are also other limitations to the existing literature on utilization of psychotropics in preschool children. First, most often the prevalence of psychotropic medication use among this population comes from studies of young children aged 2 to 4 years, from only one6–10 or a few states,11,12 making it difficult to determine whether reported prevalence is generalizable nationally; there is significant geographic variation in health care delivery and utilization.13,14 Others have focused on only 1 class of medication such as antipsychotics6,12,15,16 or on only 1 diagnosis, such as autism.7

Although the literature is not consistent in the populations that are studied, several important consistencies in findings have emerged. The prevalence of psychotropic prescriptions increases as children age1,3,6 and has increased with time.1,2 Boys are consistently more likely to receive prescriptions than are girls1,3,11 and White children are more likely than minority children to receive medications.1,3,11 Although existing studies provide important information about psychotropic utilization, we still lack a national perspective on utilization in the youngest age group.

Most psychotropic prescribing in young children is off-label, meaning that the medication has not been tested and approved by the Food and Drug Administration for use in this age group.17,18 This is understood and accepted practice as these medications are not routinely tested in young children; however, close clinical monitoring of children receiving these drugs is warranted until clinical trials establish their safety and effectiveness in this population.18 This dearth of studies including young children has made it necessary to look to other sources of data to understand how psychotropics are being used in this population.

Very young children can be more sensitive to medication side effects than adolescents or adults.19–21 Currently, we have limited knowledge of the long-term effects of antipsychotics on the developing brain and nervous system22 and there are multiple public health consequences of prescribing psychotropics to preschool children. The first 3 years of life are a period of rapid neurodevelopment, and the effect of exposure to psychotropic medications is still largely unknown.22

Metabolic side effects are one important set of side effects that can result from psychotropic exposure. Overweight and obesity are a significant problem for children, with 12% of kindergarteners already obese and 14.9% classified as overweight; these children are more likely to be overweight or obese as adults.23 In children with chronic mental illness the prevalence of overweight and obesity is greater than in the general pediatric population.24 There is also evidence of metabolic dysfunction, as significant weight gain and incidence of diabetes is significantly greater in antipsychotic- and psychotropic-exposed children.25–27 Therefore, understanding prescribing in young children is a first step to preventing or ameliorating serious side effects that could affect children’s health into adulthood.

In the current study, we examined utilization of the most commonly used psychotropic medications among children aged 4 years and younger in Medicaid programs from 36 states. Children in Medicaid are large consumers of these drugs and these prescriptions account for significant expenditures for the Medicaid program.28,29 We looked at all children aged younger than 5 years (up to age 4 years, 364 days) in calendar years 2000 through 2003 in 36 states to determine the prevalence of psychotropic medication use and indications for such use among preschool children enrolled in Medicaid programs.

METHODS

Data were Medicaid claims files from 36 states (Medicaid Analytic Extract [MAX]) for years 2000 through 2003. We used the Medicaid person summary file for enrollment and demographic information; the MAX prescription drug (RX) files provided prescription fill date and national drug codes, which were grouped following the Medicaid RX30 or Red Book31 classifications (described subsequently in this section). We obtained International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis codes32 for children from the physician outpatient (“other therapy”) and inpatient MAX files. We retained all children enrolled in fee-for-service (FFS), primary care case management (PCCM), or managed care plans with non–mental health care carve-out for at least 10 months in a calendar year; children in comprehensive and behavioral managed care plans have either no service-level claims or unreliable data.

We created 2 cohorts of children based on the birth year available in the Medicaid data. Children born in 1999 were assigned to the first cohort (for whom data were available between 2000 and 2003) and children born in 2000 were assigned to the second cohort (for whom data were available between 2001 and 2003). The purpose of creating these independent but temporally overlapping cohorts was to determine if psychotropic prescribing was associated with child age but unrelated to year of birth. Although we did observe 2 true panels in our data, some preschool children received a new prescription for a psychotropic in one of the cohort years following the beginning of the cohorts. To allow entry into the study of such new entrants, we opted to treat our data as a pooled cross-section. Such a design also permits identification of children who have gaps in eligibility for Medicaid for both individual socioeconomic and state-level financial reasons.

Psychotropic Utilization, Indication, and Associated Diagnoses

Medicaid drug claims contain national drug codes that must be aggregated across formulation and packaging. We used 2 complementary approaches, each of which provides a slightly different way of describing drug patterns. Medicaid RX,30 the most widely used Medicaid pharmacy risk adjustment model, aggregates drugs by indication at the national drug code level. The indications we chose to focus on were (1) attention-deficit disorder/attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), (2) depression or anxiety, and (3) psychotic illness or bipolar disorder because medications for these conditions were most commonly observed in our data. Second, we also used the Red Book,31 another industry-standard reference containing details on pharmaceutical classes at the national drug codes level, to aggregate on the basis of the therapeutic class of the drug. For the 3 selected commonly occurring conditions in the Medicaid RX system, we obtained drug categories from Red Book including antidepressants, tranquilizers or antipsychotics, amphetamine-type stimulants, and nonamphetamine stimulants. The combination of these 2 approaches allowed us to examine both types of medication used and the indication for which they are used, giving us a more comprehensive picture of utilization. The approaches are expected to yield slightly different results based on the way in which claims are aggregated; this happens, for example, when a drug from a single class is used for more than 1 psychiatric disorder.

We created variables for psychiatric diagnoses using primary and secondary ICD-9-CM codes from the child’s outpatient “other therapy” and inpatient files. These diagnosis-based variables included: ADHD (ICD-9-CM 314.*, with the asterisk indicating that the appropriate diagnoses are inclusive of all fourth and fifth digits); depression (ICD-9-CM 300.4, 311.*, 296.2–296.3); bipolar disorder (ICD-9-CM 296.4–296.7); psychoses (ICD-9-CM 295–296.1, 296.8–296.9, 297–299); and all other mental health (ICD-9-CM 290–294.*, 300–313, 315–319.*).

Covariates

Covariates included demographic information available in Medicaid files, which is limited to age, race/ethnicity, gender, state of residence, and Medicaid plan type. We defined age as a categorical variable based on cohort year, meaning that, for example, a child’s age was coded as 1 in the Medicaid calendar year in which the child turned 1, coded as 2 in the year that the child turned 2, etc. By design, no child was aged older than 4 years (4 years, 364 days). We collapsed race/ethnicity into White non-Hispanic, Black non-Hispanic, Hispanic ethnicity of any race, and other, unknown race, or ethnicity combinations (combined because of small sample sizes). We entered state of residence as a covariate in the regression models to adjust for state-level fixed effects, primarily related to difference in state Medicaid benefit design. Medicaid plan type was a categorical variable and included FFS, PCCM, a combination of FFS and PCCM, and other Medicaid plan types.

Statistical Analysis

We first calculated descriptive statistics for the number and percentage of children in each cohort year (age) by using each category of psychotropics (Medicaid MRX and Red Book) and for each of the covariates listed previously. To determine if any of the covariates were significantly associated with psychotropic prescribing, we fit a logistic regression model with any psychotropic prescription based on the MRX classification as the outcome at the child–year level. We defined the outcome variable as receipt of any psychotropic prescription on at least 1 Medicaid claim during 1 calendar year.

The primary independent variables were child race/ethnicity, gender, Medicaid plan type, and psychiatric diagnoses with indicator variables also included for state, cohort, age, and the interaction of cohort and age. We conducted analyses in Stata 13.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX) with clustering corrections for variance estimates at the child–year level.

RESULTS

Across ages and cohorts, 1.19% of children received any prescription for a psychotropic in the MRX categories between 2000 and 2003. The proportions of children receiving a prescription for ADHD or for depression or anxiety were similar, at 0.61% and 0.59%, respectively, and 0.24% of children received a prescription for psychotic illness or bipolar (not shown in Table 1).

TABLE 1—

Demographic and Prescription Utilization Information for Preschool Children Enrolled in Medicaid in 36 States From 2 Cohorts, Defined by Birth in 1999 (Cohort 1) or 2000 (Cohort 2): United States

| Cohort 1, % (No.) |

Cohort 2, % (No.) |

||||||

| Characteristics | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 |

| Age, y | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Boys | 51.30 (253 461) | 51.31 (222 962) | 51.38 (222 190) | 51.40 (250 704) | 51.23 (274 775) | 51.33 (239 757) | 51.31 (264 068) |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||

| White | 41.55 (205 268) | 41.41 (179 959) | 41.65 (180 098) | 43.10 (210 231) | 43.04 (230 851) | 42.09 (196 609) | 42.89 (220 732) |

| Black | 29.64 (146 426) | 31.12 (135 227) | 30.94 (133 808) | 30.46 (148 571) | 29.25 (156 857) | 30.35 (141 758) | 30.39 (156 412) |

| Hispanic | 21.21 (104 775) | 20.18 (87 694) | 20.06 (86 740) | 19.36 (94 414) | 20.07 (107 663) | 20.08 (93 780) | 19.60 (100 858) |

| Other or unknown race | 7.61 (37 595) | 7.29 (31 665) | 7.35 (31 791) | 7.08 (34 513) | 7.64 (40 981) | 7.48 (34 915) | 7.13 (36 679) |

| Insurance | |||||||

| PCCM | 28.34 (140 016) | 31.75 (137 969) | 28.87 (124 841) | 33.24 (162 140) | 31.20 (167 342) | 29.79 (139 126) | 34.15 (175 745) |

| FFS | 51.66 (25 524) | 52.82 (229 539) | 49.66 (214 757) | 51.68 (252 041) | 51.60 (276 776) | 48.70 (227 442) | 50.91 (262 049) |

| FFS and PCCM | 12.48 (61 662) | 7.39 (32 094) | 13.22 (57 185) | 7.00 (34 120) | 9.91 (53 144) | 13.47 (62 927) | 7.17 (36 892) |

| Other insurance | 7.52 (37 138) | 8.04 (34 943) | 8.24 (35 654) | 8.08 (39 428) | 7.29 (39 090) | 8.04 (37 567) | 7.77 (39 995) |

| Medication | |||||||

| For ADHD | 0.02 (76) | 0.05 (226) | 0.35 (1 493) | 1.43 (6 951) | 0.01 (65) | 0.06 (269) | 0.37 (1 905) |

| For depression or anxiety | 0.15 (748) | 0.26 (1 114) | 0.47 (2 046) | 0.77 (3 752) | 0.15 (791) | 0.27 (1 283) | 0.43 (2 231) |

| For psychotic illness or bipolar disorder | 0.01 (59) | 0.04 (158) | 0.17 (720) | 0.48 (2 362) | 0.01 (46) | 0.04 (205) | 0.19 (974) |

| For any ADHD, depression, anxiety, psychotic, or bipolar disorder | 0.17 (857) | 0.32 (1 404) | 0.85 (3 686) | 2.15 (10 496) | 0.16 (873) | 0.35 (1 649) | 0.84 (4 334) |

| Claims diagnosis | |||||||

| ADHD | 0.01 (42) | 0.03 (136) | 0.12 (509) | 0.38 (1 851) | 0.01 (40) | 0.03 (139) | 0.14 (746) |

| Depression | 0.01 (70) | 0.02 (69) | 0.02 (67) | 0.01 (33) | 0.02 (102) | 0.01 (69) | 0.01 (32) |

| Bipolar | 0.00 (3) | 0.00 (2) | 0.00 (10) | 0.01 (47) | 0.00 (5) | 0.00 (4) | 0.00 (18) |

| Psychoses | 0.00 (8) | 0.02 (94) | 0.08 (363) | 0.16 (800) | 0.00 (13) | 0.02 (98) | 0.10 (503) |

| Any claims diagnosis | 0.02 (123) | 0.07 (298) | 0.22 (935) | 0.54 (2 653) | 0.03 (160) | 0.07 (307) | 0.25 (1 271) |

Notes. ADHD = attention-deficit disorder/attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; FFS = fee for service; PCCM = primary care case management. Total population varied between 434 545 and 536 352 per cohort per year.

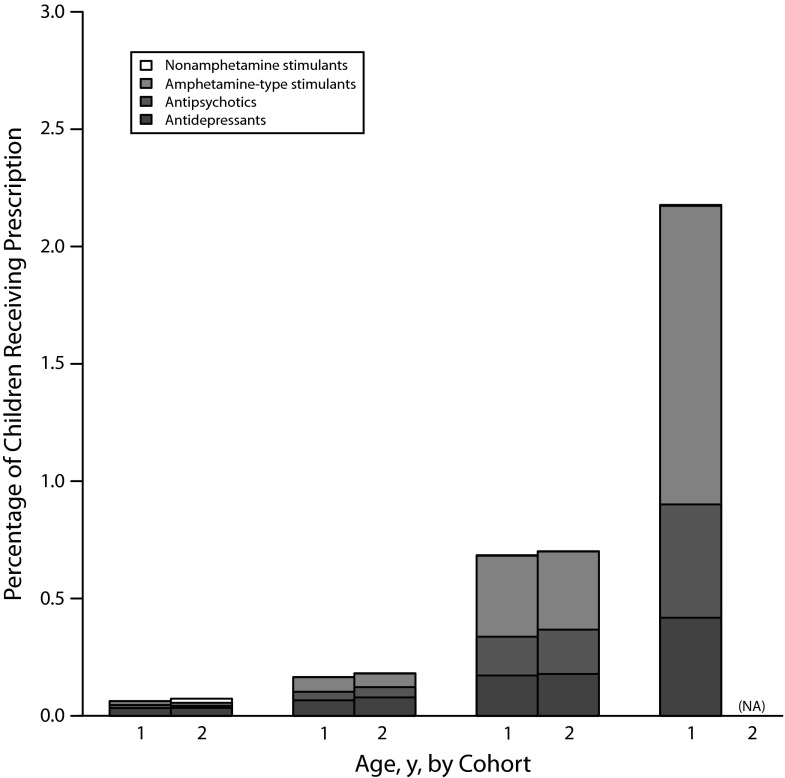

In Figure 1 we show the proportion of prescriptions for each Red Book drug code for the cohort born in 1999 (cohort 1) and the cohort born in 2000 (cohort 2) at each age, up to 4 years of age (cohort 1) or 3 years of age (cohort 2).1 This includes both children who had multiple drug claims in multiple calendar years and those who filled a drug claim in only 1 calendar year. The most common medication classes were amphetamine-type stimulants (0.55%), followed by antidepressants (0.26%), tranquilizers or antipsychotics (0.24%), and, finally, very few children received nonamphetamine stimulants (0.01%). Psychotropic utilization increased with increasing age of children. Across Red Book categories (data not shown) a total of 0.84% of children received a prescription from the categories of antidepressants, tranquilizers or antipsychotics, amphetamine-type stimulants, and nonamphetamine stimulants combined.

FIGURE 1—

The percentage of preschool children enrolled in Medicaid in 36 states from 2 cohorts, defined by birth in 1999 (cohort 1) or 2000 (cohort 2), receiving prescriptions for each Red Book drug code for all children aged 4 years and younger in each cohort year: United States.

Note. Data were not available after 2003.

The most commonly prescribed medications for each of the Red Book categories were as follows: antidepressants (sertraline hydrochloride [13.4%]); tranquilizers/antipsychotics (risperidone [72.7%]); amphetamine-type stimulants (amphetamine salt combination [49.2%]) and nonamphetamine stimulants (caffeine citrate [78.7%]).

In Table 1 we present demographic and prescription utilization information for our sample. We obtained aggregate demographics from the last year that children were observed; these figures are not shown in the table. Children were 51% male, 43% White, 29% Black, 20% Hispanic, and 8% other or unknown race. Approximately half of children (51%) were enrolled in FFS-only insurance, 31% in PCCM-only, 9% in a combination of FFS and PCCM, and 9% in another insurance type. The most common diagnosis in this population was ADHD (0.2%), followed by psychoses (0.1%), depression (0.02%), and finally bipolar (0.005%). Diagnoses increased as children aged in both cohorts (Table 1)

In the logistic regression analysis (Table 2), boys had 1.80 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.74, 1.86) times the odds of girls of receiving a prescription for psychotropics. Children of other or unknown race had 1.75 times the odds of use compared with Whites (95% CI = 1.66, 1.85). On the other hand, Black and Hispanic children had one half to one third the odds of use, with odds ratios of 0.51 (95% CI = 0.48, 0.53) and 0.37 (95% CI = 0.34, 0.39), respectively, relative to White children. Compared with those with FFS-only insurance, children with only PCCM or a combination of PCCM and FFS had 0.64 to 0.67 times the odds of receiving prescription psychotropics. All results were statistically significant at a P level of less than .05. Children with other nonbehavioral health carve-out insurance types had 1.14 (95% CI = 1.01, 1.28; P < .01) times the odds of use as those in traditional FFS-only Medicaid. Children with a claims diagnosis of any of the included psychiatric disorders had increased odds of use of psychotropic medication. Across ages, ADHD was the most common diagnosis and diagnoses increased with age, though bipolar was extremely uncommon at all ages but strongly associated with medication use. All results were statistically significant (P < .01).

TABLE 2—

Association of Demographic and Insurance Characteristics With Receiving Any Psychotropic Prescription in Children Aged 1 to 4 Years in Medicaid Programs From 36 States: United States, 1999–2003

| Characteristic | OR (95% CI) |

| Male | 1.80*** (1.74, 1.86) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White (Ref) | 1.00 |

| Black | 0.51*** (0.48, 0.53) |

| Hispanic | 0.37*** (0.34, 0.39) |

| Other or unknown race | 1.75*** (1.66, 1.85) |

| Insurance | |

| FFS (Ref) | 1.00 |

| PCCM | 0.67*** (0.63, 0.71) |

| PCCM and FFS | 0.64*** (0.60, 0.69) |

| Other insurance | 1.14* (1.01, 1.28) |

| Claims diagnosis | |

| ADHD | 81.14*** (74.97, 87.82) |

| Depression | 3.02** (1.31, 6.94) |

| Bipolar | 101.52*** (56.28, 183.14) |

| Psychoses | 12.63*** (10.86, 14.69) |

Notes. ADHD = attention-deficit disorder/attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; CI = confidence interval; FFS = fee for service; OR = odds ratio; PCCM = primary care case management. We controlled for the following in the model: state, cohort, age, and the interaction of cohort and age. Data were not available after 2003. Total observations = 3 366 862. Wald χ2 = 36281.2; P < .001; McFadden’s pseudo R2 = 0.15.

*P < .05; **P < .01; ***P < .001.

DISCUSSION

In the overall sample of children aged 4 years and younger in Medicaid data from 36 states, we found that, between 2000 and 2003, 1.19% of children received a prescription for any ADHD, depression or anxiety, or psychotic illness or bipolar medication. In addition, 0.17% of infants aged younger than 1 year, and 0.34% of children aged between 1 and 2 years were being prescribed psychotropic drugs. Across ages and cohorts, 0.61% of children received a prescription for ADHD, 0.59% for depression or anxiety, and 0.24% for psychotic illness or bipolar. With Red Book codes, 0.55% were receiving amphetamine-type stimulants, 0.26% antidepressants, 0.24% tranquilizers or antipsychotics, and 0.01% nonamphetamine stimulants. The distribution of prescriptions within each age group changed as children aged, with depression or anxiety predominating in 1- and 2-year-olds with increasing prescriptions for ADHD and psychotic illness or bipolar in the 3- and 4-year-olds. By age 4 years, ADHD was the most common prescription category. Others have also found an association between psychiatric diagnoses and medication receipt with, for example, children diagnosed with externalizing disorders more likely to receive antipsychotics,33 or with medication rates highest in children with ADHD and mood disorders.3 Although the absolute numbers and percentages of these drugs were small, these findings are worrying in so far as they indicate the use of psychotropic drugs among very young children.

Although this study provides evidence of the use of psychotropic drugs, it does not provide definitive evidence that these drugs are used for psychiatric disorders that are being diagnosed among these children. Our data do contain diagnostic codes, which reveal diagnoses of any of the psychiatric disorders in the 0.25% to 0.54% range for 3- to 4-year-olds; however, diagnoses are endogenous with the psychotropic medications, leading to artificially inflated odds ratios. In addition, diagnoses in Medicaid data based on ICD-9 codes are known to suffer from validity problems, and therefore should be interpreted carefully. Lacking chart data, we have no way of determining the specific indication or behavioral symptom for which the child was prescribed the drug. For this reason, these findings cannot be interpreted as evidence of the prevalence of psychiatric disorders among these children, nor of the appropriateness of the prescribing of psychotropic drugs for such conditions. Furthermore, the fact that a drug prescription was filled does not necessarily mean that the child consumed the drug.34 We cannot rule out the potential diversion of drugs, especially ADHD drugs, for recreational purposes.

Our findings have both agreement and differences with other studies that have used Medicaid data. Consistent with other studies, we found that prescribing increased as children aged,1,3,6 that boys were more likely to receive prescriptions than girls,1,3,11 and that White children were more likely to receive a prescription than minority children.1,3,11 But in contrast with our study, Zito et al.,1 for example, found that 2.3% of 2- to 4-year-olds from 7 states received 1 or more psychotropic prescription in 2001. Part of this discrepancy with our findings may be the use of different medication classification schemes than MRX or Red Book, but more likely our estimate is lower because we included children from birth through age 4 years as opposed to ages 2 through 4 years and prescribing increases with age. Although use of psychotropics is low at very young ages, our results show that it is nonzero, making the case that simple exclusions omit important categories of use that should be investigated.

In a second study, Zito et al. compared psychotropic utilization in children from 3 countries and included children aged 0 to 4 years. They found that in a US sample of state Children’s Health Insurance Program children with income twice the federal poverty level, 0.88% of 0- to 4-year-olds received any psychotropic drug in 2000.35 The limitation of this estimate is that data came from only 1 state and, by definition of State Children’s Health Insurance Program eligibility, children were selected from higher-income families than most children in Medicaid. Overall, our estimate of 1.19% falls within the range of existing estimates but may be more representative because of the large size of our sample, including data from 36 states covering 89% of the US population.

The fact that even 1% to 2% of very young children may be receiving psychotropic drugs is worrisome given current lack of evidence that they are safe and effective in this age group. Although we cannot comment on the appropriateness of medication use among such young children, it is clear that such use can have serious adverse consequences for their health and well-being, many of which are as yet poorly understood. It is possible that at least some of such prescribing is occurring because of the nonavailability of behavioral interventions for young children, especially in rural or economically disadvantaged areas. Given the dearth of child psychiatrists in many regions, it is likely that such prescribing patterns reflect attempts by nonspecialty physicians to achieve symptom control for the child. Both of these scenarios raise quality-of-care concerns, and underline the need for a concerted, multiagency response that expands access to specialty and psychosocial services so that children with complex clinical presentations can be comprehensively assessed and appropriately treated.

Our study’s results should be interpreted in the light of some limitations. The age of our data set does not reflect current utilization. We observed drug fills, and not drug consumption, in our claims data. However, there is no evidence from metrics such as the medication possession ratio that suggests that filled drugs are not taken.34 We do not have chart information so we cannot look at appropriateness of prescribing, and the small number of individuals prevents us from doing a geographic decomposition; therefore, we cannot look at practice pattern differences across the country.

Despite these limitations, these findings indicate that very young children in the Medicaid program are receiving psychotropics. Finding ways to appropriately treat preschool children with behavioral disorders is critical to enhancing their well-being.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH092312 and T32 MH019960), the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (2T32 HL007456-26), the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R01 HS020269), and the National Institute of Mental Health Office for Research in Disparities and Global Mental Health (HHSN271201200644P).

This material was presented on November 18, 2014, at the 2014 American Public Health Association Annual Meeting in New Orleans, LA.

Thank you to Eric Westhus, PhD, for preparing the figure.

Human Participant Protection

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards at Washington University in St Louis and RTI International.

References

- 1.Zito JM, Safer DJ, Valluri S, Gardner JF, Korelitz JJ, Mattison DR. Psychotherapeutic medication prevalence in Medicaid-insured preschoolers. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2007;17(2):195–203. doi: 10.1089/cap.2007.0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Olfson M, Crystal S, Huang C, Gerhard T. Trends in antipsychotic drug use by very young, privately insured children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(1):13–23. doi: 10.1097/00004583-201001000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chirdkiatgumchai V, Xiao H, Fredstrom BK et al. National trends in psychotropic medication use in young children: 1994–2009. Pediatrics. 2013;132(4):615–623. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zito JM, Safer DJ, Gardner JF, Boles M, Lynch F. Trends in the prescribing of psychotropic medications to preschoolers. JAMA. 2000;283(8):1025–1030. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.8.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olfson M, Blanco C, Wang S, Laje G, Correll CU. National trends in the mental health care of children, adolescents, and adults by office-based physicians. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(1):81–90. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.3074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Constantine RJ, Jentz S, Bengtson M, McPherson M, Andel R, Jones MB. Exposure to antipsychotic medications over a 4-year period among children who initiated antipsychotic treatment before their sixth birthday. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2012;21(2):152–160. doi: 10.1002/pds.2189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Williams PG, Woods C, Stevenson M, Davis DW, Radmacher P, Smith M. Psychotropic medication use in children with autism in the Kentucky Medicaid population. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2012;51(10):923–927. doi: 10.1177/0009922812440837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luby JL, Stalets MM, Belden AC. Psychotropic prescriptions in a sample including both healthy and mood and disruptive disordered preschoolers: relationships to diagnosis, impairment, prescriber type, and assessment methods. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2007;17(2):205–215. doi: 10.1089/cap.2007.0023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ferguson DG, Glesener DC, Raschick M. Psychotropic drug use with European American and American Indian children in foster care. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2006;16(4):474–481. doi: 10.1089/cap.2006.16.474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin A, Van Hoof T, Stubbe D, Sherwin T, Scahill L. Multiple psychotropic pharmacotherapy among child and adolescent enrollees in Connecticut Medicaid managed care. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54(1):72–77. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.dosReis S, Zito JM, Safer DJ, Gardner JF, Puccia KB, Owens PL. Multiple psychotropic medication use for youths: a two-state comparison. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2005;15(1):68–77. doi: 10.1089/cap.2005.15.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patel NC. Antipsychotic use in children and adolescents from 1996 to 2001: epidemiology, prescribing practices, and relationships with service utilization. Ann Arbor, MI: ProQuest Information and Learning; 2005.

- 13.Morrato EH, Druss B, Hartung DM et al. Small area variation and geographic and patient-specific determinants of metabolic testing in antipsychotic users. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20(1):66–75. doi: 10.1002/pds.2062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leslie LK, Raghavan R, Hurley M, Zhang J, Landsverk J, Aarons G. Investigating geographic variation in use of psychotropic medications among youth in child welfare. Child Abuse Negl. 2011;35(5):333–342. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matone M, Localio R, Huang Y, dosReis S, Feudtner C, Rubin D. The relationship between mental health diagnosis and treatment with second-generation antipsychotics over time: a national study of U.S. Medicaid-enrolled children. Health Serv Res. 2012;47(5):1836–1860. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01461.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Medicaid Medical Directors Learning Network, Rutgers Center for Education and Research on Mental Health Therapeutics. Antipsychotic medication use in Medicaid children and adolescents: report and resource guide from a 16-state study. 2010. Available at: http://rci.rutgers.edu/∼cseap/MMDLNAPKIDS.html. Accessed October 1, 2014.

- 17.Coyle JT. Psychotropic drug use in very young children. JAMA. 2000;283(8):1059–1060. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.8.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zito JM, Derivan AT, Kratochvil CJ, Safer DJ, Fegert JM, Greenhill LL. Child and adolescent psychiatry and mental health. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2008;2(1):24. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-2-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Safer DJ, Zito JM. Treatment-emergent adverse events from selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors by age group: children versus adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2006;16(1-2):159–169. doi: 10.1089/cap.2006.16.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Safer DJ. A comparison of risperidone-induced weight gain across the age span. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;24(4):429–436. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000130558.86125.5b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wigal SB, Gupta S, Greenhill L et al. Pharmacokinetics of methylphenidate in preschoolers with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2007;17(2):153–164. doi: 10.1089/cap.2007.0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fanton J, Gleason MM. Psychopharmacology and preschoolers: a critical review of current conditions. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2009;18(3):753–771. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2009.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cunningham SA, Kramer MR, Narayan KM. Incidence of childhood obesity in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(5):403–411. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1309753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vieweg WV, Kuhnley LJ, Kuhnley EJ et al. Body mass index (BMI) in newly admitted child and adolescent psychiatric inpatients. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2005;29(4):511–515. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Correll CU, Carlson HE. Endocrine and metabolic adverse effects of psychotropic medications in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(7):771–791. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000220851.94392.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Biederman J, Mick E, Wozniak J, Aleardi M, Spencer T, Faraone SV. An open-label trial of risperidone in children and adolescents with bipolar disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2005;15(2):311–317. doi: 10.1089/cap.2005.15.311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bobo WV, Cooper WO, Stein CM et al. Antipsychotics and the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in children and youth. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(10):1067–1075. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Raghavan R, Brown DS, Thompson H, Ettner SL, Clements LM, Key W. Medicaid expenditures on psychotropic medications for children in the child welfare system. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2012;22(3):182–189. doi: 10.1089/cap.2011.0135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Raghavan R, Brown DS, Allaire BT, Garfield LD, Ross RE. Medicaid expenditures on psychotropic medications for maltreated children: a study of 36 states. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(12):1445–1451. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201400028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gilmer T, Kronick R, Fishman P, Ganiats TG. The Medicaid Rx model: pharmacy-based risk adjustment for public programs. Med Care. 2001;39(11):1188–1202. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200111000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Thompson Reuters: Red Book 2011. Available at: http://www.redbook.com. Accessed September 21, 2011.

- 32.International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 1980. DHHS publication PHS 80–1260. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zito JM, Burcu M, Ibe A, Safer DJ, Magder LS. Antipsychotic use by Medicaid-insured youths: impact of eligibility and psychiatric diagnosis across a decade. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(3):223–229. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karve S, Cleves MA, Helm M, Hudson TJ, West DS, Martin BC. An empirical basis for standardizing adherence measures derived from administrative claims data among diabetic patients. Med Care. 2008;46(11):1125–1133. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31817924d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zito JM, Safer DJ, de Jong-van den Berg LT et al. A three-country comparison of psychotropic medication prevalence in youth. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2008;2(1):26. doi: 10.1186/1753-2000-2-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]