Abstract

Objectives. In an antifluoridation case study, we explored digital pandemics and the social spread of scientifically inaccurate health information across the Web, and we considered the potential health effects.

Methods. Using the social networking site Facebook and the open source applications Netvizz and Gephi, we analyzed the connectedness of antifluoride networks as a measure of social influence, the social diffusion of information based on conversations about a sample scientific publication as a measure of spread, and the engagement and sentiment about the publication as a measure of attitudes and behaviors.

Results. Our study sample was significantly more connected than was the social networking site overall (P < .001). Social diffusion was evident; users were forced to navigate multiple pages or never reached the sample publication being discussed 60% and 12% of the time, respectively. Users had a 1 in 2 chance of encountering negative and nonempirical content about fluoride unrelated to the sample publication.

Conclusions. Network sociology may be as influential as the information content and scientific validity of a particular health topic discussed using social media. Public health must employ social strategies for improved communication management.

Approximately 74% of Internet users in the United States use social networking sites1 such as Facebook, which has 1 billion users worldwide, and YouTube, which is the second most used search engine globally.2 Much of the content shared peer-to-peer across these and other social sites is copied from, derivative of, or in response to traditional media content.3 News sites, Facebook, YouTube, and blogs are among the “most trustworthy” sources for retail information, and all have a strong influence on purchasing decisions,4 demonstrating the power of both expert and professional and amateur- and peer-created content. Additionally, 8 of 10 Internet users seek health information online.5 This collective evidence suggests that these Internet users are likely using social media sites to obtain health information.6

Although social networks play a vital role in health behaviors,7–9 searching for health information online can be problematic, specifically information on childhood vaccinations and community water fluoridation (CWF, or fluoridation). Decreasing childhood vaccination rates and preventable disease outbreaks in the United States have resulted in widespread discussion across mainstream and social media sites in recent years.8–17 Yet, according to 1 study, because of deficient reporting by popular media, less than 25% of survey respondents were aware that the majority of scientific evidence supports the safety and effectiveness of vaccines.18

Additionally, antifluoride activists are organizing on social media sites19 with the intention of lobbying the Environmental Protection Agency’s Office of Water, despite having proposed arguments that do not align with current scientific consensus about CWF in the United States.20–22 The Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education Appropriations Bill 2015 subcommittee draft report states, “The Committee is concerned about conflicting information in the media regarding the benefits of community fluoridation.”23 Seemingly, communication challenges contributing to suboptimal beliefs and behaviors about these leading24 public health interventions do not exist in isolation.

Public health is encountering an emerging threat of “digital pandemics,” the rapid far-reaching spread of unrestricted and scientifically inaccurate health information across the Web through social networks.25 Improved communication between researchers and media reporters is indeed recommended but is only part of the solution. Public health challenges stemming from online misinformation are at the complex intersection of scientific research, mass media, and the emergence of social network activism through user-created content and consumer reception of information.

We performed, to our knowledge, a first of its kind observational study designed to explore this challenge and the epidemiology of digital pandemics.

METHODS

We selected the topic of fluoridation because the benefits continue to be debated online, despite current scientific consensus on its safety and efficacy. Additionally, a recent publication on developmental neurotoxicity in children recommended that fluoride be added to the list of currently identified neurotoxicants,26 which created a measurable response in mainstream and social media regarding CWF.25 Our study consisted of 3 phases of observation: (1) the connectedness within and between antifluoride networks as a measure of social influence, (2) the social diffusion of CWF information on the basis of the publication as a measure of spread, and (3) the networks’ engagement in and sentiment about that information as a measure of attitudes and behaviors. All data we collected were aggregated, anonymous, and either publically available or posted by users who consented to the privacy terms and usage policies of the social network site we studied.

Because of its high public influence and usage, we selected Facebook for observation from February to July 2014. We studied a sample of 9 public antifluoride advocacy groups, consisting of 12 534 members, which was a subset of approximately 27 541 users from all existing antifluoride groups we located. We studied these groups because they were either open groups or accepted our request to join, which was necessary for data collection. To minimize reactivity bias, we did not interact with members of the groups after sending an initial request to join if applicable. We used 2 open source tools for our analysis, the Facebook data extraction application Netvizz, version 1.01 (Bernhard Rieder, Amsterdam, Netherlands) and the data visualization tool Gephi, version 0.8.2-beta (Gephi Consortium, Paris, France).27

Connectedness and Betweenness Centrality

We measured and mapped the connectedness (number of online friendship connections) within and between the study sample groups, where a node represented an individual member and an edge represented the friendship connection between members. Using Gephi’s preprogrammed algorithm, we then measured and mapped betweenness centrality, a metric that captures the influence of a member in a network on the basis of the level of connectivity.28 We conducted a 1-sample t test measuring the weighted means of average path lengths of our sample networks compared with Facebook’s reported overall average path length of 4.74.29 Average path length is a metric that defines, on average, how many nodes any random node must pass through to connect to any other random node (sometimes referred to as “degrees of separation”). Shorter average path lengths indicate higher connectedness of a network.

Social Diffusion of Information

We observed the social diffusion of the scientific article from our sample networks. Hereafter, we will refer to the article as the “original source” and any post, blog, or other Web page that referenced it as a “reference post.” We performed a keyword search using Facebook’s search tool and identified and cataloged 16 reference posts by 7 of our 9 groups since the article’s publication, approximately 6 months; 2 of the groups did not post about the article. Although “dislike” is not a feature of Facebook, individuals who disliked a comment could respond to a comment with a link that demonstrated his or her dislike of the original comment; we also included these links in our link analysis if present in a comment from our data set.

We then performed a manual spider crawl by tracing each of the 16 posts back to the original source via reference links in the posts, cataloguing every link along the way to find all possible paths leading back to the source. If a path failed to lead to the original source after 3 links, or degrees, we deemed this path a dead end. We chose 3 degrees for several reasons. First, on the basis of industry reporting for how long an individual might spend linking to information before feeling content with an answer to a question (5 minutes as 1 example), exploring a maximum of 3 links reasonably fulfills this timeframe.30 Second, after 3 links, the conversations frequently were no longer relevant to the topic and had taken us away from the subject of interest. Third, incorporating more than 3 links in our visualization map made the nodes and edges too indistinguishable from one another for adequate visual analysis.

Using Gephi, we input and graphed our information diffusion map beginning from the original source, where nodes represent the online platforms where the reference post exists (whether it linked directly to the original source or linked to another reference post) and the edges are the links between them. We only mapped the first link to dead ends to minimize the number of nodes and edges on the diffusion network map for improved visualization. Mapping diffusion allowed us to track the types of connections about our original source as well as the degrees of separation between a reference node on Facebook and the original source. The diffusion analysis also created the ability to begin to interpret, through engagement and sentiment, how information morphs and becomes misrepresented with increasing distance between a social reference post and the original source. We quantified the proportion of dead ends of the total number of links in the pathways that existed in the social diffusion network.

Engagement and Sentiment

Engagement with a post is measured by the number of “likes” (a user can click a “like” button to demonstrate and record her approval), comments (users can comment on a post), and subcomments (users can comment on another user’s comment about a post). Because “dislikes” or anything similar are not a feature of Facebook, we captured the sentiment of “dislike” as part of the qualitative sentiment analysis of comments we conducted. In general, the industry standard for social marketing has determined that the higher the engagement a post elicits the more influential it is and the more likely it is to influence behavior.31,32 We identified the 2 Facebook posts from our social diffusion map with the highest degree of engagement. We determined that additional posts beyond these 2 did not have enough engagement to alter our results significantly, so we did not study any additional posts.

We analyzed all comments on these 2 posts with 10 or more likes, as these were determined to be the most influential comments on the posts because of their high levels of engagement. We used inductive coding by identifying sentiment patterns and subsequently categorizing recurrent keywords and phrases into common themes (Table 1). Inductive coding allowed the development of codes that were strictly grounded in the data and avoided imposing preexisting codes when they might not apply. We outlined initial themes and codes on the basis of the individual comments and we refined them as we evaluated more raw data.

TABLE 1—

Theme Descriptions, Keywords, and Examples From the Qualitative Comment Analysis: February to July 2014

| Theme | Definition | Keywords or Identifiers | Examples |

| Science based | User employs or attempts to use scientific evidence, terms, or analysis to make the argument (whether accurate or not) | science | “I read this article and the data are mainly from rural areas of China where fluoride is high naturally.” |

| analysis of Lancet | “Small amts of fluoride in a municipal water supply have been shown to be beneficial . . . it’s all in the dosage.” | ||

| dose | |||

| moderation | |||

| quantity | |||

| research | |||

| reference | |||

| evidence | |||

| Autonomy | User makes an argument about individual rights and choice | government | “Boils down to choice . . . should NOT be forced on the general population.” |

| vote | “Whose [sic] all in favor of a class action lawsuit against the government for poisoning us.” | ||

| rights | |||

| choice | |||

| opinion | |||

| debate | |||

| forced medication | |||

| Ad hominem | User attacks the ethos of those holding differing views | stupid | “People saying this [expletive] are stupid . . . fluoride damages the body.” |

| idiot | “Aaaaand 90% of people here are scientifically illiterate and have not bothered to actually read the article. You blithering idiots can’t even explain what your [sic] talking about.” | ||

| illiterate | |||

| obscenities | |||

| Conspiracy theory | User hypothesizes ulterior motives or intentions for using fluoride | big pharma | “Hitler saw the added effect of fluoride in controlling the masses.” |

| money | “The government is killing people daily and keeping us sick to keep pharmacies in business. It’s a never ending cycle.” | ||

| corporate America | |||

| Hitler | |||

| insecticide | |||

| pineal gland | |||

| Selected or anecdotal evidence | User employs personal experience of hearsay | my water | “Soooo I live in a place where the water is not fluorinated [sic] and my teeth and gums are great.” |

| friend | “I have never met a single person with any kind of disability that has been medically blamed on fluoride.” | ||

| neighbor | |||

| personal identifiers | |||

| Disputing the evidence | User shows lack of scientific literacy and skepticism of the research article, science, expert consensus, or scientific concepts in general | Lancet vaccine article | “. . . the whole nonsense about vaccines and autism started with a fraudulent ‘study.’ . . . SO lets [sic] not all celebrate just because more junk was published once again.” |

| past mistakes | “. . . sure fluoride (sadly not the naturally occurring version [sic]) is good for our oral hygiene so the dentist uses it, but why are we drinking it again? It’s not good for our organs is it?” | ||

| questioning benefits | |||

| Null | User posts a comment unrelated to the topic | not applicable | “Why does it matter . . . we are all on our way out anyways right?” |

Note. “Science based” and “Disputing the evidence” are antithetical. Although the former attempts to employ scientific evidence or approach as a form of argumentation, the latter discredits the scientific method and rejects its validity as a way of ascertaining facts.

We cataloged every comment to a theme, assigned a corresponding discrete variable sentiment score (−1 = antifluoride, 0 = neutral or not applicable, 1 = profluoride), and calculated an engagement score. We used the following formula, designed on the basis of industry standard, for measuring engagement:

|

where x is the number of likes, y is the number of comments, and z is the number of subcomments. We tested and confirmed our coding approach for interrater agreement with 2 independent coders. Because we reached saturation before this number, we did not complete the analysis for subcomments, as we felt this would not bring in any new information and instead would be redundant.

RESULTS

Our results consisted of outcomes from 3 phases of observation over a 6-month period: (1) the connectedness within and between antifluoride networks as a measure of social influence, (2) the social diffusion of CWF information on the basis of the publication as a measure of spread, and (3) the networks’ engagement in and sentiment about that information as a measure of attitudes and behaviors.

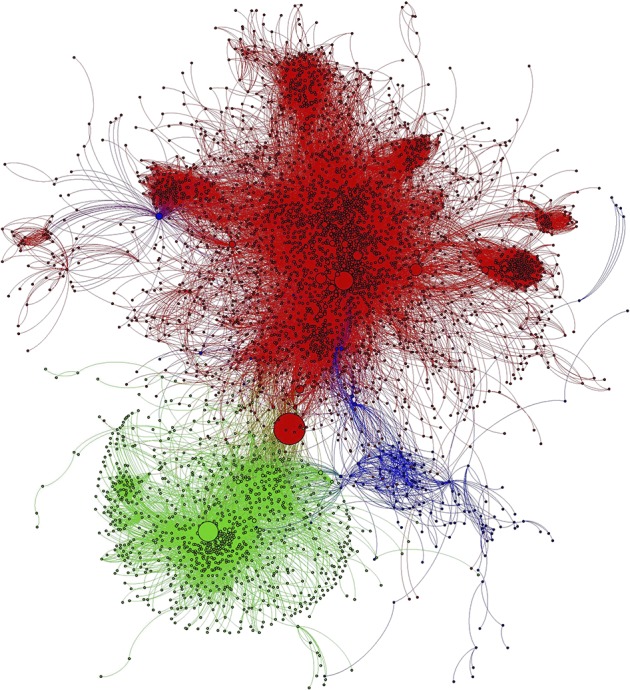

Connectedness and Betweenness Centrality

On average, the antifluoride Facebook groups in our sample were highly intraconnected, with approximately 9 of 10 members having friend connections with 1 or more other members in their respective group. Our sample networks followed a scale-free or power law distribution relative to the degree distribution of the network with redundant and strong ties, which is believed to be typical of social networks.33–35 However, the weighted mean path length of our study sample was significantly shorter than was that of Facebook overall (P < .001), meaning our study sample networks are significantly more connected.

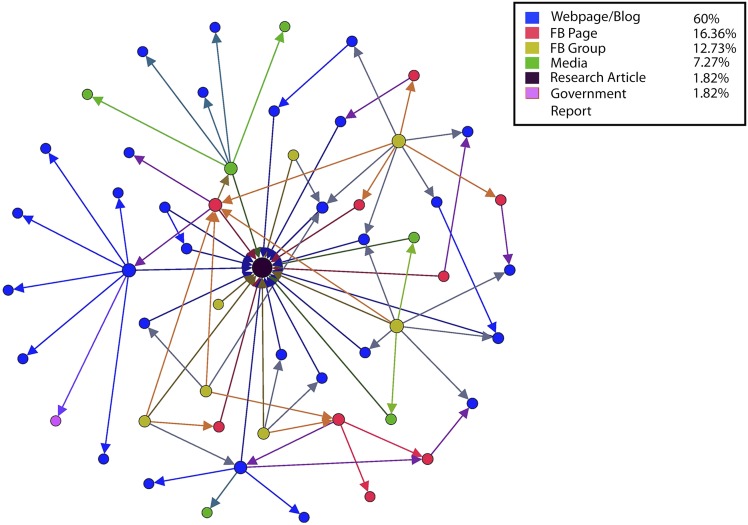

Figure 1 demonstrates 3 randomly selected groups from our study sample for elucidatory and visual purposes and to illustrate these findings. The illustration shows the color-coded distribution of these 3 groups by Facebook identification, where the separate colors represent the separate Facebook groups, each node represents a group member, and the edges represent the connection between members. The size of the node illustrates the betweenness centrality of that group member. Larger nodes, nicknamed “mayors” of their own networks, tended to be more influential in their network. Larger nodes that had connections between networks are considered strong “influencers” beyond their own networks.31 Figure 1 illustrates the existence of influencers in our sample networks, represented by large nodes of differing colors possessing edges that connect to nodes in another network. In addition to their size as an indication of connectivity, nodes in 1 group that are highly connected to nodes in another group will display edge connections that are a blend of the 2 group colors. This effect can be clearly seen with the highly connected node in the upper left portion of Figure 1 with purple edges, a blend of the red and blue group edge colors.

FIGURE 1—

Social networks of 3 antifluoride groups, color-coded by Facebook group identification: July 2014.

Social Diffusion of Information

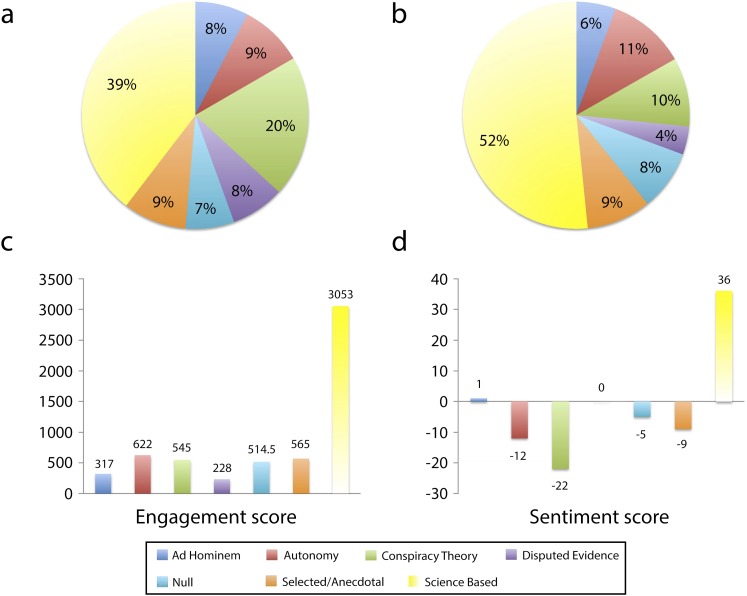

Figure 2 illustrates the original source article in the center, the 16 posts about the article found in our 9 antifluoride groups since the time of publication, plus all additional reference posts 2 degrees from those 16 (eliminating dead ends)—a total of 54 reference posts. The arrows demonstrate the directionality of the information diffusion, meaning if a node (post, Web page or blog, and so on) referenced another node, the arrow points to the node that was referenced, and the edge represents that link. Social diffusion is evident and can be tracked in Figure 2 from node to node through the edges by directionality.

FIGURE 2—

Social diffusion map of information from social media and digital platforms traced to the original scientific article being diffused or discussed: February to July 2014.

Thirty-one nodes are 2 or 3 degrees from the original source, meaning that nearly 60% of the time, a user would need to follow 2 to 3 links to arrive at the original source. Furthermore, a user was guaranteed to fail in getting back to the original source 12% of the time (assuming that a user was equally likely to follow any particular path of diffusion over another by selecting links). Our results demonstrate that, on average, there was a high risk that antifluoride Facebook group members engaged in posts about the article would be forced to navigate through multiple pages to locate the original post or would never succeed in locating it at all, greatly increasing the likelihood for the spread of misinformation and misrepresentation of the scientific article’s content.

Engagement and Sentiment

We analyzed the level of engagement (influence) and sentiment of the most influential posts to explore the user experience with social diffusion of information and to determine how these posts could potentially influence group member attitudes and behaviors. Considering the distance between reference posts and the original source, this is particularly important.

Qualitative and quantitative results from the 2 most influential posts from the social diffusion map were highly similar; therefore, we combined them for reporting purposes. These 2 posts drew more than 4500 individual user engagements from multiple different groups, making them the most influential posts in our antifluoride study population. We analyzed the most influential comments (144 total) on the posts.

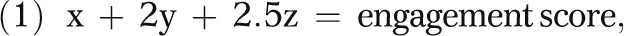

Figure 3 illustrates the combined engagement and sentiment of comments about the 2 posts. The most frequent type of comment about the posts and the type of comment that received the most engagement were the science-based comments, 57 of the 144 comments analyzed. The remaining other categories of comments cumulatively comprised the majority of comments (87 total) as well as approximately half of the engagement with the posts (2162 unique engagements). Science-based comments overall received a positive (profluoride) total sentiment score of 36 (additive over all comments), whereas all other types of comments received an overall negative (antifluoride) sentiment score of −47.

FIGURE 3—

Combined engagement and sentiment scores of 2 influential social media posts by theme to show (a) comments by type (n = 144), (b) likes by type of comment (n = 4504), (c) engagement score by comment type, and (d) sentiment score by comment type: February to July 2014.

These results demonstrate that the user experience, when engaging with these influential posts, is just as likely to be negative and irrelevant to the original source as it is to be positive and reference scientific information (accurate or not). Our results demonstrate a high probability (1 in 2 chance) of encountering negative and non–science-based information about fluoride that is unrelated to the original peer-reviewed scientific publication under discussion.

DISCUSSION

Peer-to-peer influence remains a primary factor in shaping individual attitudes and behaviors, including those related to health; consequently, connected individuals influence one another to adopt similar behaviors.9,31,36,37 Furthermore, choice homophily means individuals with preexisting similar traits are more likely to form social connections.9 Accordingly, networks built from choice homophily and strengthened through high connectedness begin to develop normative values and structured behaviors that define how the network operates.9,36,37 The strong and redundant ties found in our highly connected sample antifluoride groups increase the likelihood for peer-to-peer influence and development of strict normative behaviors in those networks. Violation of these norms, such as the introduction of scientifically accurate profluoride evidence or corrective information, likely results in rejection of any expert-based opinion that challenges normative group values and assumptions in that network.36–39

High betweenness centrality of individuals in our sample networks, specifically the presence of mayors and influencers, illuminates the emerging role social media may be playing in affecting health behaviors and outcomes. Historically, naturally limiting factors such as geography and communication barriers inhibited opportunities for strengthening networks with outlying views.40 Risky behaviors as a result of shared moral evaluations,36 such as opting out of recommended childhood vaccination schedules and rejecting fluoridation, reverberated in existing small networks without necessarily scaling to dangerous magnitudes.

Our results suggest that online social networking allows greater connectivity among networks through the increased visibility of group behavior; previously nonnormative behaviors can thus become normative through the use of social media.40 This hidden-to-visible switch creates higher likelihood for “contagious” activity online through confirmation bias and the influence of an expanding network.36,41 Furthermore, high betweenness centrality creates new opportunities for social diffusion of (mis-)information by creating ties, even weak ones, that expand a message to entirely new networks of people, allowing ideas and information to spread more rapidly. Additionally, strong ties in networks reinforce the sentiments carried with that message once it reaches a new network.9,31,36 Expert opinion grounded in evidence that contradicts the sentiments embedded in a socially diffused message will be quickly rejected; acceptance of this contradictory information would be socially detrimental to the network, challenging its very identity.38,39 Thus marks the beginning of digital pandemics of misguided and incomplete health information in which evidence becomes entirely secondary to the sociology of the networks diffusing it.

Limitations

Because of the novel and highly exploratory nature of this study, limitations exist. First, we must not overrepresent the number of users on social media relative to the general public as a whole, particularly the number of those who are using it to obtain and evaluate health information. A technology divide exists between those who are literate in social media and those who may not have access to or an understanding of social media.

Second, our explorative approach analyzed activity about a very specific public health intervention: community water fluoridation. Further study is necessary to determine if our findings are generalizable to networks and discussions about other public health topics; however, we believe the potential for generalization exists because caregiver refusal of childhood immunizations was recently associated with topical fluoride refusal.42 Third, further study is needed to determine how online engagement in a discussion about CWF or any health topic translates to real-life behaviors and health outcomes.

Finally, ethical considerations about privacy, informed consent, and analyzing user-generated content for research purposes, which likely does not align with the users’ intentions for engaging, must always remain a consideration when conducting this type of study. Thus, we restricted our methodology by only evaluating publically available and open source data to respect these ethical considerations to the best of our ability.

Conclusions

The scientific community has yet to fully use the potential of social media, even though scientists recognize the general public’s high level of engagement in online social networking.2,43 As we see a rise in user-created content across the Web and the emergence of new terms such as “expert patient,”6 and “citizen journalist,”38 the boundaries between expert authority and quasiproficiency are increasingly blurring. Traditional vertical health communication strategies, such as broadcast diffusion through peer review publication and media reporting, may no longer be effective because of the existence and viral potential of social diffusion.31

Our results demonstrate the viability of our hypothesis that the sociology of networks is perhaps just as influential as, if not more influential than, the information content and scientific validity of a particular health topic discussed within and between certain networks via social media. We have introduced a novel and integrated approach to the problem of digital pandemics in public health by analyzing people networks, the social diffusion of information, and the user experience.

Outcomes from this study suggest additional areas for research. How do existing social strategy research outcomes from the business and marketing sectors translate to health, if at all? What can public health researchers learn about the sociology of networks and their influence through new technologies? Do digital pandemics translate to poor health outcomes? Despite the limitations of this viability study, our findings strongly suggest a need for additional research to better understand the complexities that exist at the intersection of scientific research, responsible journalism, and layperson contributions to content creation and information diffusion and reception.

Further study could allow public health to adopt and adapt novel and emerging business sector approaches (including those of nonprofit, government, and private enterprises) for targeting consumers’ decision-making behavior through social marketing4,40 and thus begin to develop social strategies40 for improved health communication management in an increasingly interconnected world. Empirical social strategies for health communication should focus not only on high-quality digital information production and dissemination but also on socially targeted and custom-designed messaging that conforms to the norms and values of specific target networks rather than challenging them. Developing an appreciation for the sociology of target groups could assist public health experts in increasing influence in problem networks and could provide the tools to predict, prevent, or reverse digital pandemics.

Just as the power of the Internet surprised traditional authority with its capability to dismantle longstanding institutions,44 so may have the public health community underestimated social media’s capacity for influence on health behavior. The public nature of social media is at once a barrier to accurate information flow online and a tremendous opportunity for public health research, innovation, and intervention. In an age when negative digital pandemics can go viral, public health communication management strategies must go social.

Acknowledgments

This publication resulted, in part, from a round table sponsored by the Harvard Global Health Institute and the Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard and from research supported by the Harvard Global Health Institute’s Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship and founding faculty director Sue J. Goldie.

We wish to acknowledge Harvard School of Dental Medicine’s Department of Oral Health Policy for making this study possible and statistical support from Alfa I. Yansane, PhD. We also wish to thank the digital innovation agency Social Driver and the Harvard Social Media and Global Health Collaborative advisory group for their insight and expertise.

Human Participant Protection

Our study was granted exemption status by the committee on human studies at Harvard Medical School because the research involved the observation of public behavior and the collection of publically available existing information and participants were unidentifiable.

References

- 1.Pew Research Center. Social networking fact sheet. Available at: http://www.pewinternet.org/fact-sheets/social-networking-fact-sheet. Accessed August 21, 2014.

- 2.Burke-Garcia A, Scally G.Trending now: future directions in digital media for the public health sector J Public Health (Oxf) 201436(4)527–534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nahon K, Hemsley J. Going Viral. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Higgins S. Technocrati media 2013 digital influence report. 2013. Available at: http://technorati.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/06/tm2013DIR1.pdf. Accessed August 21, 2014.

- 5.Fox S, Jones S. The Social Life of Health Information. Washington, DC: Pew Internet and American Life Project; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sudau F, Friede T, Grabowski J, Koschack J, Makedonski P, Himmel W. Sources of information and behavioral patterns in online health forums: observational study. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16(1):e10. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smith KP, Christakis NA. Social networks and health. Annu Rev Sociol. 2008;34:405–429. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pampel FC, Krueger PM, Denney JT. Socioeconomic disparities in health behaviors. Annu Rev Sociol. 2010;36:349–370. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.012809.102529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centola D. Social media and the science of health behavior. Circulation. 2013;127(21):2135–2144. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.101816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kata A. Anti-vaccine activists, web 2.0, and the postmodern paradigm—an overview of tactics and tropes used online by the anti-vaccination movement. Vaccine. 2012;30(25):3778–3789. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.11.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wilson K, Keelan J. Social media and the empowering of opponents of medical technologies: the case of anti-vaccinationism. J Med Internet Res. 2013;15(5):e103. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gross L. A. broken trust: lessons from the vaccine—autism wars. PLoS Biol. 2009;7(5):e1000114. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Atwell JE, Van Otterloo J, Zipprich J et al. Nonmedical vaccine exemptions and pertussis in California, 2010. Pediatrics. 2013;132(4):624–630. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones AM, Omer BS, Bednarczyk RA, Halsey NA, Moulton LH, Salmon DA. Parents’ source of vaccine information and impact on vaccine attitudes, beliefs, and nonmedical exemptions. Adv Prev Med. 2012;2012:932741. doi: 10.1155/2012/932741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith PJ, Chu SY, Barker LE. Children who have received no vaccines: who are they and where do they live? Pediatrics. 2004;114(1):187–195. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.1.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Omer SB, Enger KS, Moulton LH, Halsey NA, Stokley S, Salmon DA. Geographic clustering of nonmedical exemptions to school immunization requirements and associations with geographic clustering of pertussis. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168(12):1389–1396. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccine-preventable diseases, immunizations, and MMWR—1961–2011. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2011;60(suppl 4):49–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dobson R. Media misled the public over the MMR vaccine, study says. BMJ. 2003;326(7399):1107. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7399.1107-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fluoride Action Network. 2014 FAN conference. 2014. Available at: http://fluoridealert.org/content/bulletin_04-13-14. Accessed August 7, 2014.

- 20.Committee on Fluoride in Drinking Water; National Research Council. Fluoride in Drinking Water: A Scientific Review of EPA’s Standards. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Broadbent JM, Thomson WM, Ramrakha S et al. Community water fluoridation and intelligence: prospective study in New Zealand. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(1):72–76. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parnell C, Whelton H, O’Mullane D. Water fluoridation. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2009;10(3):141–148. doi: 10.1007/BF03262675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Senate Appropriations Committee. 2015 Department of Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education, and Related Agencies Subcommittee draft subcommittee report. Available at: http://www.appropriations.senate.gov/sites/default/files/LHHS%20Report%20w%20Chart%2007REPT.PDF. Accessed November 4, 2014.

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2013. Ten great public health achievements in the 20th century. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/about/history/tengpha.htm. Accessed August 7, 2014.

- 25.Seymour B. An emerging threat of “digital pandemics”—lessons learned from the anti-vaccine movement. 2014. Available at: http://aphaih.wordpress.com/2014/04/05/an-emerging-threat-of-digital-pandemics-lessons-learned-from-the-anti-vaccine-movement. Accessed August 7, 2014.

- 26.Grandjean P, Landrigan PJ. Neurobehavioural effects of developmental toxicity. Lancet Neurol. 2014;13(3):330–338. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(13)70278-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bastian M, Heymann S, Jacomy M. Gephi: an open source software for exploring and manipulating networks. 2009. Available at: https://gephi.org/publications/gephi-bastian-feb09.pdf. Accessed November 23, 2014.

- 28.Freeman LC. A set of measures of centrality based on betweenness. Sociometry. 1977;40(1):35–41. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Backston L, Boldi P, Rosa M, Ugander J, Vigna S. Four degrees of separation. 2012. Available at: http://arxiv.org/pdf/1111.4570v3.pdf. Accessed August 21, 2014.

- 30.Worldwide DEI. Engaging consumers online: the impact of social media on purchasing behavior. 2008. Available at: http://www.deiworldwide.com/files/DEIStudy-Engaging%20ConsumersOnline-Summary.pdf. Accessed May 7, 2009.

- 31.Goel S, Anderson A, Hofman J, Watts DJ. The structural virality of online discussion. 2013. Available at: http://5harad.com/papers/twiral.pdf. Accessed July 31, 2014.

- 32.Neiger BL, Thackeray R, Burton SH, Giraud-Carrier CG, Fagen MC. Evaluating social media’s capacity to develop engaged audiences in health promotion settings: use of Twitter metrics as a case study. Health Promot Pract. 2013;14(2):157–162. doi: 10.1177/1524839912469378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muchnik L, Pei S, Parra LC et al. Origins of power-law degree distribution in the heterogeneity of human activity in social networks. Sci Rep. 2013;3:1783. doi: 10.1038/srep01783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adamic LA, Lukose RM, Puniyani AR, Huberman BA. Search in power-law networks. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 2001;64(4 pt 2):046135. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.64.046135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Barabási AL, Albert R. Emergence of scaling in random networks. Science. 1999;286(5439):509–512. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5439.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kahan D, Braman D, Jenkins-Smith H. Cultural cognition of scientific consensus. J Risk Res. 2010;14:147–174. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baumeister RF, Zhang L, Vohs KD. Gossip as cultural learning. Rev Gen Psychol. 2004;8(2):111–121. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Patterson T. Informing the News: The Need for Knowledge-Based Journalism. New York, NY: Vintage Books; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brownstein AL. Biased predecision processing. Psychol Bull. 2003;129(4):545–568. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.4.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Piskorski MJ. A Social Strategy: How We Profit From Social Media. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Berger J. Contagious: Why Things Catch On. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chi DL. Caregivers who refuse preventive care for their children: the relationship between immunization and topical fluoride refusal. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(7):1327–1333. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Allgaier J, Dunwoody S, Brossard D, Lo Y, Peters HP. Journalism and social media as means of observing the contexts of science. Bioscience. 2013;63(4):284–287. [Google Scholar]