Abstract

We analyzed the case of the World Health Organization’s Commission on Social Determinants of Health, which did not address gender identity in their final report.

We argue that gender identity is increasingly being recognized as an important social determinant of health (SDH) that results in health inequities. We identify right to health mechanisms, such as established human rights instruments, as suitable policy tools for addressing gender identity as an SDH to improve health equity.

We urge the World Health Organization to add gender identity as an SDH in its conceptual framework for action on the SDHs and to develop and implement specific recommendations for addressing gender identity as an SDH.

Gender identity is frequently overlooked when social determinants of health (SDHs) are being discussed. We analyzed the case of the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) Commission on Social Determinants of Health as an initial driver of the SDH movement, which did not address gender identity in their final report published in 2008.1 Subsequent international initiatives focused on the SDHs, such as the Rio Political Declaration on the Social Determinants of Health2 adopted in 2011 and the WHO European Review of the Social Determinants of Health and the Health Divide3 published in 2012, have also omitted gender identity. We argue that gender identity is increasingly being recognized as an important SDH that results in health inequities and should be addressed to improve health equity, including through the application of human rights instruments.

THE SOCIAL DETERMINANTS OF HEALTH AND HEALTH EQUITY

The WHO defines SDHs as “the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age” and that are “shaped by the distribution of money, power and resources.”4 Health inequities are the avoidable, remediable, and unfair inequalities in health outcomes between different populations.4 The unequal distribution of SDHs causes health inequities.1 Because SDH-focused policy and action aim to increase the health of disadvantaged populations, the SDH movement works explicitly toward greater social justice.1

In 2005, the WHO established the commission to synthesize theoretical and empirical evidence and make recommendations for action on the SDHs to improve health equity. A crucial foundation for the commission’s work was the development of its conceptual framework,1 which identified and theorized key SDHs.5 The commission’s milestone final report set the scene and recommended actions for “closing the gap in a generation.”1 Current international and national policy development and action on SDHs is generally predicated on the commission’s concepts and recommendations.

HEALTH INEQUALITIES BY GENDER IDENTITY

Gender identity is “each person’s deeply felt internal and individual experience of gender, which may or may not correspond with the sex assigned at birth.” This can include “the personal sense of the body (which may involve, if freely chosen, modification of bodily appearance or function by medical, surgical or other means) and other expressions of gender, including dress, speech and mannerisms.”6(p6) People whose individual experience of gender does not (always) correspond with their assigned sex commonly call themselves “transgender.” Other terms have been used to describe minority gender identities in different cultures and contexts. Examples include some “two-spirit” identities among American Indians and Alaska Natives, “fa’afafine” and “fa’atama” in Samoa, “hijra” in India, and “kathoey” in Thailand (Reisner et al. provide a review of international terminology7). The term “cisgender” has been introduced for people whose gender and assigned sex correspond.8 Recent studies in the United States have estimated that 0.3%–0.5% of the population identifies as transgender.9,10 If the transgender population is defined by certain measurement concepts other than identity (e.g., by nonconforming gender expression), a considerably higher population prevalence would be expected. We have focused on gender identity because the health effects of this dimension of gender are relatively well understood, but other gender dimensions (e.g., gender expression and beliefs about gender) are increasingly being studied in health research11 and may also warrant consideration within an SDH framework. Note that sexual orientation, which comprises sexual attraction, behavior, and identity, is conceptually distinct from gender identity.12 Transgender people can be sexually attracted to and engage in sexual behavior with people of any gender and can adopt diverse sexual identities. Intersex, referring to “biological variation in sex characteristics including chromosomes, gonads, and/or genitals that do not allow an individual to be distinctly identified as female/male sex binary at birth,” is also a concept distinct from gender identity.7(p10)

Public health research has demonstrated health inequalities by gender identity, with transgender populations experiencing considerable health disadvantage, especially in the areas of mental health, sexual health, and access to health care.13 A review of nonrandom surveys indicated that up to one third of transgender participants reported having ever attempted suicide.14 A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies from 15 countries found an odds ratio for HIV infection in male-to-female transgender women compared with all adults of 48.8 (95% confidence interval = 21.2, 76.3), which was consistent across low-, middle- and high-income countries.15 HIV prevalence data are lacking for female-to-male transgender men,16 but a recent San Francisco study of sexual health clinic attendees found similar incidence among transgender men and transgender women (10% and 11%, respectively, over 3 years).17 Barriers for accessing gender-affirmative health care (psychotherapy, hormone treatment, and surgery)18 have also been identified as considerable threats to transgender health.19,20 These barriers include costs, discrimination experiences, and unavailability of transgender-competent health care professionals.19,20 For example, of the 6450 transgender participants of one US survey, the majority had postponed gender-affirmative health care (48% because they lacked funding and 28% because of discrimination); 19% reported having been refused care, 28% reported harassment, and 2% reported experiencing violence in health care because of being transgender; and 50% had had to teach health care professionals about transgender care.21,22 Health and health care inequalities are particularly marked for transgender people who are also members of other marginalized groups.23

Social exclusion is a key causal pathway for the relationship between gender identity and disadvantageous health outcomes.24 It can take the form of prejudice; stigma; transphobia (negative attitudes and feelings toward transgender people); individual, institutional, and societal discrimination; and violence.25 This pathway is conceptualized in the minority stress model, which proposes that social exclusion causes minority stress, which then either directly or through health-detrimental coping behaviors (e.g., substance use) causes worse health outcomes in transgender people.8,24,26 This model is empirically supported by recent evidence that experiences of gender abuse are associated with clinical depression among transgender women27 and predict clinical depression, sexual risk behaviors, and incidence of sexually transmitted infections, including HIV, among transgender men.28 A recent review of survey data concluded “that violence against transgender people starts early in life, that transgender people are at risk for multiple types and incidences of violence, and that this threat lasts throughout their lives.”29(p170) In the United States, transgender people are nearly 5 times as likely to have been incarcerated than is the general population and are at considerable risk of exposure to police violence21; a police training initiative was launched this year to address this concern.30 Discrimination against transgender people in housing and employment is permitted in 36 US states.31 Correspondingly, despite being more highly educated than the general population, transgender people experience higher rates of homelessness and unemployment as well as lower incomes.21 Research has demonstrated that experiences of discrimination and stigmatization are associated with psychological distress among transgender people.26 The recently published fifth edition of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders retained “gender dysphoria” as a mental disorder.32 Transgender people have perceived this decision as stigmatizing and harmful but also noted that US health insurance providers will cover care only for classified diseases.33 As part of the WHO’s current revision of the International Classification of Diseases, the Working Group on the Classification of Sexual Disorders and Sexual Health aims to move from a psychopathological model of transgender people to an evidence-based model responsive to health care needs,34 but transgender communities have critiqued the planned categories and proposed alternatives.35,36

GENDER IDENTITY AS A SOCIAL DETERMINANT OF HEALTH

Prejudice, stigma, transphobia, discrimination, and violence targeted at transgender people produce differential levels of social exclusion for populations defined by gender identity, including in health care settings. These social conditions disadvantage transgender people through social exclusion and privilege cisgender people through social inclusion. This differential level of social exclusion results in differential health outcomes, producing relatively worse health in transgender populations than in cisgender populations. So, although gender identity in itself does not determine health, it socially stratifies the population into differential exposures to SDHs such as transphobia. Gender identity is similar to more established social stratifiers such as ethnicity1 and sexual orientation,37 which influence health through such SDHs as racism and homophobia and biphobia. We refer to gender identity as a proxy for SDHs such as transphobia in the same way that ethnicity and sexual orientation are called SDHs to proxy the SDH racism and homophobia and biphobia. Thus, the evidence demonstrates that gender identity fulfils the WHO definition of an SDH.4

Because health inequalities by gender identity (like those by ethnicity1 and sexual orientation37) are socially produced, they are avoidable, remediable, and unfair. For example, state-level policies prohibiting discrimination on the basis of gender identity or expression in housing and employment would be expected to improve the health of transgender populations in the same way that policies prohibiting sexual orientation discrimination in housing and employment have improved the health of sexual minorities.38 Therefore, the health inequalities burdening transgender people are, according to WHO definition,4 health inequities.

THE COMMISSION AND GENDER IDENTITY

The commission’s conceptual framework5 included “gender”39 as an SDH, and its final report1 made recommendations for addressing health inequities between women and men. However, the conceptual framework5 did not include “gender identity” as an SDH, and the final report1 did not mention the term “gender identity” or refer to populations defined by gender identity. This is despite the commission’s dedicated Women and Gender Equity Knowledge Network repeatedly emphasizing the considerable health disadvantage of transgender populations in its final report40 to the commission. The WHO’s implementation of the commission’s recommendations has also not addressed gender identity.2,3 (Sexual orientation was similarly excluded from the commission’s and WHO’s subsequent work, and the case for addressing sexual orientation as an SDH has convincingly been made.37)

The commission’s final report1 was a groundbreaking blueprint for policy and action by governments and others to address SDHs and health equity. However, the former United Nations (UN) special rapporteur for the right to health Professor Paul Hunt noted that “the commission’s report represents a series of missed opportunities,” because “despite the multiple, dense connections between social determinants and human rights, the report’s human rights content is disappointingly muted.”41(p40) The lack of inclusion of gender identity as an SDH and lack of proposed action to address the health disadvantage of transgender populations is a concrete example of such a missed opportunity.

A CALL FOR ACTION

The commission called for greater social justice through raising awareness to and stimulating action on the SDHs to improve the health of the most disadvantaged populations. The evidence demonstrates that gender identity is an SDH and that transgender people experience considerable health disadvantage. Transgender people’s right to health is often not respected, let alone protected or fulfilled.16 Thus, in line with its call for greater social justice, the SDH movement should also address gender identity to improve health equity.

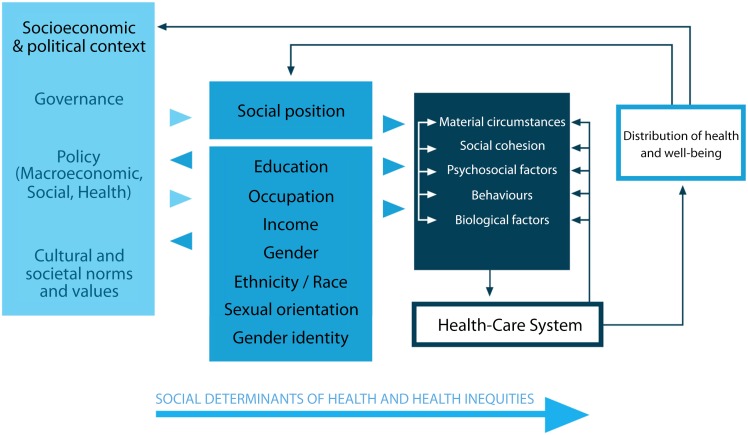

We propose that the WHO, as the leader in global health, take two steps toward addressing gender identity to improve health equity. First, we urge the WHO to add gender identity as an intermediary SDH to the commission’s conceptual framework for action, as presented in Figure 1. (Following Logie’s call,37 this proposed adapted framework also includes sexual orientation as an SDH.) To support this change, we recommend that the WHO also provide a definition for gender identity (distinguishing it from the WHO definitions for sex and gender)39 and explain how gender identity socially determines health. Gender identity should be added alongside gender, because these two SDHs differ conceptually and define different health inequities (those between transgender and cisgender people vs those between women and men). As definitional and conceptual research on diverse dimensions of gender and health research on these dimensions advances, additional dimensions may require consideration within the SDH framework. Second, we urge the WHO to develop, publish, and implement specific recommendations for addressing gender identity and related health inequities. These proposed changes should be developed and implemented under guidance from and in collaboration with transgender communities. Particular emphasis should be placed on ensuring transgender people’s right to health, including freedom from discrimination on the basis of gender identity as one component of the right to accessible health services. The WHO’s current International Classification of Diseases review also heralds an opportunity to reduce the stigmatization and marginalization of transgender people.35,36

FIGURE 1—

Conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health including gender identity.

Source. Adapted from the World Health Organization’s Commission on Social Determinants of Health.1

Note. We have included sexual orientation as a social determinant of health per Logie’s recommendation.37

The WHO has recently actively combined SDHs and right to health–based approaches for improving health equity.42 Addressing gender identity as an SDH offers the opportunity for the WHO to advance this line. The UN Secretariat, the UN Human Rights Council, and the wider human rights community are increasingly attending to transgender people’s right to health. This right is guaranteed in several UN human rights treaties,41 and its application in relation to gender identity is outlined in The Yogyakarta Principles.6 International and national human rights instruments have already been used to raise awareness of and stimulate action on the transgender health disadvantage.

At the international level, UN member states and civil society have used the Universal Periodic Review process to hold states accountable for failing to protect transgender people’s health. For example, in the 2010 Universal Periodic Review, the National Coalition for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Health submitted that transgender people in the United States are not protected by law from discrimination and are not guaranteed access to health care in several states.43

At the national level, several mechanisms for protecting transgender people’s right to health exist. For example, the US Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights recently clarified that Title IX prohibits discrimination against students on the basis of gender identity or expression and that it accepts complaints against such discrimination,44 providing a mechanism for protecting transgender students’ right to health in educational settings. In New Zealand, the Human Rights Commission conducted the Transgender Inquiry in 2008 and on the basis of its results recommended improving access to and the quality of health care for transgender people,45 and, as a result, the Ministry of Health published national best practice guidelines for gender-affirmative health care in 2011.46 These established human rights instruments may be particularly effective in stimulating the political will and public policy to address gender identity for improving health equity.

CONCLUSIONS

Gender identity is an SDH, and transgender populations experience considerable health disadvantage. The commission and subsequent WHO work did not include gender identity in their conceptual framework and did not recommend or pursue action on gender identity. We urge the WHO to add gender identity as an SDH in its conceptual framework and to develop and implement dedicated recommendations for addressing gender identity to improve health equity, including through application of human rights instruments.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the University of Otago through a Health Sciences Career Development Programme postdoctoral fellowship (to F. P.); the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research through a postdoctoral research fellowship (to J. F. V.); and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (grant 300958 to J. F. V.).

We thank Asher Bruskin, Jack Byrne, Kumanan Rasanathan, and Randall L. Sell for feedback on an earlier version of the article.

Note. The funding agencies were not involved in the preparation, review, or approval of the commentary.

Human Participant Protection

No protocol approval was necessary because the study did not involve human participants.

References

- 1.Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity Through Action on the Social Determinants of Health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Rio Political Declaration on Social Determinants of Health. Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: 2011. Available at: http://www.who.int/sdhconference/declaration/en. Accessed on January 13, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marmot M, Allen J, Bell R et al. WHO European review of social determinants of health and the health divide. Lancet. 2012;380(9846):1011–1029. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61228-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. Social determinants of health: what are the social determinants of health? 2014. Available at: http://www.who.int/social_determinants/sdh_definition/en. Accessed March 22, 2014.

- 5.Solar O, Irwin A. A Conceptual Framework for Action on the Social Determinants of Health: Debates, Policy & Practice, Case Studies. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6.International Commission of Jurists. The Yogyakarta principles: principles on the application of international human rights law in relation to sexual orientation and gender identity. 2006. Available at: http://www.yogyakartaprinciples.org. Accessed November 3, 2014.

- 7.Reisner SL, Lloyd J, Baral SD. Technical Report: The Global Health Needs of Transgender Populations. Arlington, VA: USAID’s AIDS Support and Technical Assistance Resources; AIDSTAR-Two; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reisner SL, Greytak EA, Parsons JT, Ybarra ML. Gender minority social stress in adolescence: disparities in adolescent bullying and substance use by gender identity. J Sex Res. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2014.886321. April 17, 2014:1–14. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gates G. How Many People Are Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender? Los Angeles, CA: Williams Institute, University of California, Los Angeles; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conron KJ, Scott G, Stowell GS, Landers SJ. Transgender health in Massachusetts: results from a household probability sample of adults. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(1):118–122. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conron KJ, Landers SJ, Reisner SL, Sell RL. Sex and gender in the US health surveillance system: a call to action. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(6):970–976. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sell R. Defining and measuring sexual orientation in research. In: Meyer I, Northridge M, editors. The Health of Sexual Minorities: Public Health Perspectives on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Populations. New York: Springer; 2007. pp. 355–374. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Institute of Medicine. The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People: Building a Foundation for Better Understanding. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Haas AP, Eliason M, Mays VM et al. Suicide and suicide risk in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations: review and recommendations. J Homosex. 2011;58(1):10–51. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2011.534038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baral SD, Poteat T, Strömdahl S, Wirtz AL, Guadamuz TE, Beyrer C. Worldwide burden of HIV in transgender women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(3):214–222. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70315-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Byrne J. Discussion Paper: Transgender Health and Human Rights. New York, NY: United Nations Development Programme; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stephens SC, Bernstein KT, Philip SS. Male to female and female to male transgender persons have different sexual risk behaviors yet similar rates of STDs and HIV. AIDS Behav. 2011;15(3):683–686. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9773-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Selvaggi G, Bellringer J. Gender reassignment surgery: an overview. Nat Rev Urol. 2011;8(5):274–282. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2011.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sanchez NF, Sanchez JP, Danoff A. Health care utilization, barriers to care, and hormone usage among male-to-female transgender persons in New York City. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(4):713–719. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.132035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shipherd J, Green KE, Abramovitz S. Transgender clients: identifying and minimizing barriers to mental health treatment. J Gay Lesbian Ment Health. 2010;14(2):94–108. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grant J, Mottet L, Tanis J, Harrison J, Herman J, Keisling M. Injustice at Every Turn: A Report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. Washington, DC: National Center for Transgender Equality and National Gay and Lesbian Task Force; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reisner SL, Conron K, Scout N, Mimiaga MJ, Haneuse S, Bryn AS. Comparing in-person and online survey respondents in the US National Transgender Discrimination Survey: implications for transgender health research. LGBT Health. 2014;1(2):98–106. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2013.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sevelius JM. Gender affirmation: a framework for conceptualizing risk behavior among transgender women of color. Sex Roles. 2013;68(11–12):675–689. doi: 10.1007/s11199-012-0216-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hendricks ML, Testa RJ. A conceptual framework for clinical work with transgender and gender nonconforming clients: an adaptation of the Minority Stress Model. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2012;43(5):460–467. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fish J. Conceptualising social exclusion and lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people: the implications for promoting equity in nursing policy and practice. J Res Nurs. 2010;15(4):303–312. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bockting WO, Miner MH, Swinburne Romine RE, Hamilton A, Coleman E. Stigma, mental health, and resilience in an online sample of the US transgender population. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(5):943–951. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nuttbrock L, Bockting W, Rosenblum A et al. Gender abuse and major depression among transgender women: a prospective study of vulnerability and resilience. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(11):2191–2198. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nuttbrock L, Bockting W, Rosenblum A et al. Gender abuse, depressive symptoms, and HIV and other sexually transmitted infections among male-to-female transgender persons: a three-year prospective study. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(2):300–307. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stotzer RL. Violence against transgender people: a review of United States data. Aggress Violent Behav. 2009;14(3):170–179. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Department of Justice. Deputy Attorney General James M. Cole delivers remarks at the Community Relations Service Transgender Law Enforcement Training launch. 2014. Available at: http://www.justice.gov/opa/speech/deputy-attorney-general-james-m-cole-delivers-remarks-community-relations-service. Accessed November 3, 2014.

- 31.National Gay and Lesbian Task Force. State Nondiscrimination Laws in the US. Washington, DC: 2013. National Gay and Lesbian Task Force. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Drescher J. Queer diagnoses: parallels and contrasts in the history of homosexuality, gender variance, and the diagnostic and statistical manual. Arch Sex Behav. 2010;39(2):427–460. doi: 10.1007/s10508-009-9531-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Drescher J, Cohen-Kettenis P, Winter S. Minding the body: situating gender identity diagnoses in the ICD-11. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2012;24(6):568–577. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2012.741575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Global Action for Trans Equality. It’s Time for Reform: Trans Health Issues in the International Classification of Diseases. The Hague, Netherlands: 2011. Global Action for Trans Equality. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Global Action for Trans Equality. Critique and Alternative Proposal to the “Gender Incongruence of Childhood” Category in ICD-11. Buenos Aires, Argentina: 2013. Global Action for Trans Equality; [Google Scholar]

- 37.Logie C. The case for the World Health Organization’s Commission on the Social Determinants of Health to address sexual orientation. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(7):1243–1246. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hatzenbuehler ML, Keyes KM, Hasin DS. State-level policies and psychiatric morbidity in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(12):2275–2281. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.153510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.World Health Organization. What do we mean by “sex” and “gender”? 2014. Available at: http://www.who.int/gender/whatisgender/en. Accessed July 2, 2014.

- 40.Sen G, Östlin P, George A. Unequal, Unfair, Ineffective and Inefficient Gender Inequity in Health: Why It Exists and How We Can Change It: Final Report to the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Bangalore, India: Indian Institute of Management Bangalore; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hunt P. Missed opportunities: human rights and the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Glob Health Promot Educ. 2009;(suppl 1):36–41. doi: 10.1177/1757975909103747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rasanathan K, Norenhag J, Valentine N. Realizing human rights-based approaches for action on the social determinants of health. Health Hum Rights. 2010;12(2):49–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.National Coalition for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Health. Report on the United States of America Universal Periodic Review on Sexual Rights, 9th Round. Washington, DC: 2010. National Coalition for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Health; [Google Scholar]

- 44.Office for Civil Rights, Department of Education. Questions and Answers on Title IX and Sexual Violence. Washington, DC: Office for Civil Rights, Department of Education; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Human Rights Commission. To Be Who I Am: Report of the Inquiry Into Discrimination Experienced by Transgender People. Auckland, New Zealand: 2008. Human Rights Commission. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ministry of Health. Gender Reassignment Health Services for Trans People Within New Zealand. Wellington, New Zealand: 2011. Ministry of Health. [Google Scholar]