Abstract

Hyperhomocysteinemia (HHcy) is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease. However, the mechanisms of HHcy-induced arteriosclerosis are largely unknown. In this study, we investigated the role and mechanism of HHcy on vascular remodeling in a carotid arterial vein patch model.

We assessed the effect of HHcy on vascular remodeling using a carotid arterial vein patch model in mice with the gene deletion of cystathionine-β-synthase (Cbs, plasma Hcy 310 μM). Vein grafts were harvested 4 weeks after surgery. Cross sections of the transplanted vessel segment were analyzed using Verhoeff-van Gieson staining and Masson’s Trichrome staining for morphological analysis and total collagen protein level assessment. Further, the vessel sections were immunostained with antibodies against α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), type 1 collagen, CD45 (leukocyte marker), and Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen (PCNA). The effect of Hcy on collagen secretion was examined in cultured rat aortic smooth muscle cells (RASMC) by Western blot analysis. We found that Cbs−/− mice with severe HHcy exhibited thicker neointima and a higher percentage of luminal narrowing in the vein graft. In addition, severe HHcy increased elastin, total collagen, and type 1 collagen deposition in the neointima. Further, severe HHcy increases CD45 positive cells and proliferative cells in the lesions of vein grafts in Cbs−/− mice. Finally, Hcy increases collagen secretion in cultured rat aortic smooth muscle cells (RASMC).

These results demonstrate that HHcy increases neointima formation, elastin and collagen deposition following a carotid arterial vein patch. The capacity of Hcy to promote vascular fibrosis and inflammation may contribute to the development of vascular remodeling.

Keywords: atherosclerosis, homocysteine, smooth muscle cell, collagen

2. INTRODUCTION

Hyperhomocysteinemia (HHcy) is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease1. It was reported that plasma total homocysteine (Hcy) levels are a strong predictor of mortality in patients with angiographically confirmed coronary artery disease2. Several mechanisms have been proposed to explain cardiovascular pathological changes associated with HHcy. These include endothelial dysfunction and damage3, 4, dysregulation of cholesterol and triglyceride (TG) biosynthesis5, 6, thrombosis activation7, 8, and stimulation of vascular smooth muscle cell (SMC) proliferation9, 10. Although these studies established that Hcy has profound atherogenic effects, the mechanisms by which HHcy contributes to arteriosclerosis remain largely unknown.

Mechanical injury is a major cause of atherosclerosis. The most frequently occurring post-injury atherosclerosis is restenosis of the coronary artery following angioplasty or bypass surgery. Despite increased surgical experience and technical breakthroughs, restenosis occurs in 30–50% of patients undergoing simple balloon angioplasty and in 10–30% of patients who receive an intravascular stent11, 12. Therefore, experimental studies are important for a better understanding of the mechanisms for restenosis. The pathophysiology of restenosis is complex and incompletely understood. Evidence strongly suggests that restenosis is a maladaptive response of the coronary artery to trauma induced during angioplasty consisting of thrombosis, inflammation, cellular proliferation, and extracellular matrix production that together contribute to postprocedural lumen loss13, 14. It was suggested that Hcy increases collagen expression in cultured vascular SMC and in atherosclerotic plaques in apolipoprotein E (apoE) knockout mice15, 16. We previously reported that HHcy impaired reendothelialization and promoted neointima formation using a carotid artery air-dry endothelial denudation model17. However, the role of Hcy on vascular remodeling following mechanical injury has not been studied. To assess the role of HHcy in intimal hyperplasia and vascular remodeling, post-injury remodeling was evaluated using a carotid arterial vein patch model. We studied vascular remodeling in response to mechanical injury in the mice with gene deletion of cystathionine-β-synthase (Cbs). We used carotid sections for morphometric and immunohistochemical analysis to characterize cellular populations in the lesion, and to identify the expression of potential target molecules. Moreover, we observed the long-term effects of Hcy on collagen secretion in cultured rat aortic SMC (RASMC).

3. MATERIALS AND METHODS

3.1 CBS mice and Hcy measurement

A genetic HHcy model with the gene deletion of cystathionine β-synthase (CBS), which catalyzes Hcy to cystathionine, was used in the present study. CBS mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and backcrossed 6 generations to achieve approximately 98% purity in a C57BL/B6 genetic background. We used polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to genotype the mice as described17, which were all fed a regular rodent diet after weaning. All animal care and procedures conform to NIH guidelines.

We collected mouse plasma at the end of each experiment and measured Hcy concentrations by liquid chromatography electrospray tandem mass spectrometry methods using 25 μL of mouse plasma diluted to 100 μL with reverse osmosis water as previously described17.

3.2 Carotid arterial vein graft model

We performed carotid artery vein graft surgeries on 2 groups of CBS mice at the age of 12 weeks: homozygous Cbs deficient (Cbs−/−) mice (n=5) and Cbs wild-type (Cbs +/+) mice (n=9). This model mimics human coronary artery bypass surgery, which is the most effective means of treatment for patients with multivessel coronary artery disease. The mouse vein graft surgery procedure was performed on anesthetized mice under a dissecting microscope as described18. In brief, the left external jugular vein from C57 mouse was dissected from the main trunk. A segment of the jugular vein (≈5 mm long) was sutured into place to repair a longitudinal defect (about the same length as the jugular vein patch) in the left (ipsilateral) carotid artery. The graft was harvested at 4 weeks after surgery.

3.3 Histology and morphology analysis

The grafts, together with a short segment of the native carotid artery, were harvested at 4 weeks after surgery by cutting at the centre of the graft. One portion was processed for paraffin embedding and the other for cryostat sectioning. Consecutive sections (5 μm) were cut from the centre of the graft to the proximal and distal ends at the junction with the native carotid artery. In total, about 45 sections were cut and divided over 15 slides, so that every slide contained three sections at 150-μm intervals (equivalent to 30 sections). Paraffin sections were treated with Verhoeff-van Gieson staining (showing elastin as black) and subjected to quantitative morphological analysis. The neointima (NI) was defined as the region between the internal elastic lamina (IEL) and the lumen, and the percentage luminal narrowing was calculated as 100x (difference between area inside the IEL and area of the lumen ÷ area inside the IEL). Masson’s trichrome staining stained collagen content as blue. We determined elastin and collagen-positive area by using computer-assisted color gated measurements (Image-Pro Plus) and expressed the data as a percentage. Cryostat sections were immunostained with alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-α-smooth muscle actin antibody (Sigma, USA), anti-type 1 collagen antibody (Biodesign, USA), and antibodies against CD45, a common antigen of leukocytes and proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), a marker of proliferative cells (Oncogene Science, USA). The specificity of immunohistochemical staining was confirmed in relevant tissue sections by omitting primary antibodies.

3.4 Cell culture

The long-term effect of Hcy on SMC was determined by growing rat aortic smooth muscle cells (RASMC) for 3 weeks with or without Hcy in the culture medium. RASMC were cultured in DMEM medium (Gibco, USA) containing 10% CS (Bio-Whitaker, USA) at 37°C in 95% air and 5% CO2. RASMC cultures from passages 6 to 7 were used. Confluent cells were treated with 50 or 500 μM DL-Hcy (Sigma-Aldrich, USA), 0.2 mmol/L L-proline (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) and 50 mg/mL ascorbic acid (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) for an additional 3 weeks. Cell culture media were refreshed every three days.

3.5 Western blot analysis

Cell cultured medium, the supernatant, was collected for collagen secretion analysis using Western Blot. Protein was separated on 7% polyacrylamide gels and transferred it to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, which were then incubated with rabbit anti-rat type 1 collagen 1 monoclonal antibody (1:500) (Biodesign, USA). Blot was stained with Ponceau S for loading control.

3.6 Statistic methods

Data was expressed as mean ± SEM. Statistical comparison of animal results was analyzed by the unpaired t test using the SPSS 17.0 software. p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

4. RESULTS

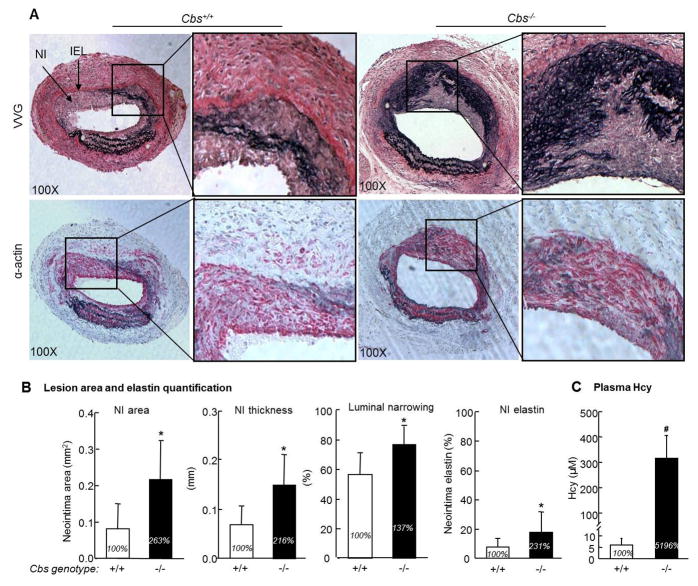

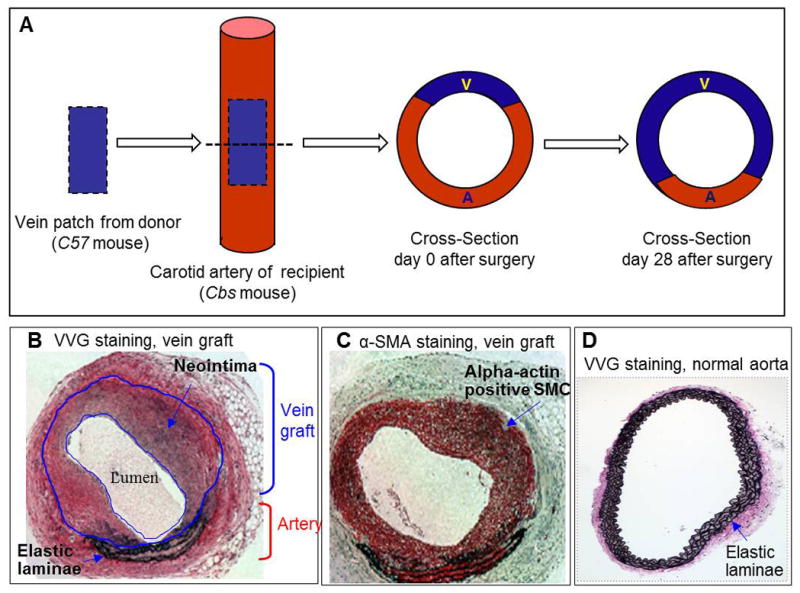

4.1 HHcy accelerates post-injury neointima formation in Cbs−/− mice

In response to arterial blood pressure, the vein graft shows outward expansion. A robust neointima lines much of the venous portion of the arterial wall at 4 weeks after surgery (Figure 1A and 1B). This model is highly reproducible in neointimal formation. Most of the newly formed neointima stained positive for α-SMA, which is consistent with a smooth muscle cell phenotype (Figure 1C). We found that HHcy Cbs−/− mice (plasma Hcy 310 μm) had significant larger and thicker neointima and a higher percentage of luminal narrowing compared with that in Cbs+/+ mice (Figure 2B).

Figure 1. Mouse carotid arterial vein patch model.

The mouse vein graft surgery procedure was performed on Cbs mice at the age of 12 weeks. The left external jugular vein from a C57 mouse was dissected from the main trunk. A segment of the jugular vein (≈5 mm long) was sutured into place to repair a longitudinal defect (about the same length as the jugular vein patch) in the left carotid artery from Cbs mouse. The grafts, together with a short segment of the native carotid artery, were harvested at 4 weeks after surgery by cutting at the center of the graft. One portion was processed for paraffin embedding and the other for cryostat sectioning. A. Schema of the vein graft and cross-section of the composite vessel at the center of the graft. B. Verhoeff-van Gieson (VVG) staining in paraffin-embedded cross-section from center of the graft of mice at 4 weeks post-operation. 3–4 layers of elastic lamina mark the artery. The vein is greatly enlarged in response to arterial blood pressure. C. α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) immunostaining in vein graft cryostat section from Cbs−/− mice at 4 weeks post-operation. Vascular smooth muscle cell appears red. D. Verhoeff-van Gieson (VVG) staining in paraffin embedded cross-section of aorta from normal mice. Notice that normal artery has well-organized and circumferentially-oriented elastin.

Figure 2. Severe HHcy promotes vascular remodeling and elastin production in the neointima in the vein graft in Cbs−/− mice.

The mouse vein graft surgery procedure was performed on Cbs mice at the age of 12 weeks as described in Figure 1 and in the section of Methods. The vein patch grafts, together with a short segment of the native carotid artery, were harvested at 4 weeks after surgery and processed for paraffin embedding (VVG) and cryostat sections (α–actin). Mouse plasma was collected at the end of each experiment (at age 16 weeks). A. Photomicrographs of morphological analysis. Sections are oriented with a vein patch on top and artery on bottom. VVG staining shows elastin as black. Anti-α-mouse smooth muscle (α-SMA) antibody staining shows smooth muscle cell as red. B. Quantitative analysis. Neointimal area and thickness were analyzed by computerized planimetry using the updated Image-Pro Plus program. We determined the elastin positive area by computer-assisted color gated measurement (Image-Pro Plus) and expressed the data as a percentage. The neointima was defined as the region between the internal elastic lamina (IEL) and the lumen. The percentage luminal narrowing was calculated as 100 x (the difference between area inside the IEL and area of the lumen ÷ the area inside the IEL. Hcy significantly increased neointima formation, luminal narrowing and neointima elastin deposition. C. Plasma level of Hcy. Hcy concentration was measured by liquid chromatography electrospray tandem mass spectrometry methods. Values represent mean±SEM, n=9, p values from independent t test * p<0.05 versus Cbs+/+ group, #p<0.001 versus Cbs+/+ group. VVG, Verhoeff-van Gieson staining.

4.2 HHcy increases neointimal elastin deposition in Cbs−/− mice

Verheoff-van Gieson staining indicates the presence of elastin with a black stain. Normal artery has well-organized and circumferentially oriented elastin laminea (Figure 1D). However, the neointimal elastin is disordered and fragmented (Figure 2A). Elastin protein is greatly increased and much disordered in the neointimal area of vein grafts in Cbs−/− mice compared with that in Cbs+/+ mice (Figure 2A). Elastin level, expressed as a percentage of area, accounted for 17.87±1.70% of the neointimal area in Cbs−/− mice in comparison with 7.74±2.95% of the neointimal area in Cbs+/+ mice (p<0.05, Fig 2B).

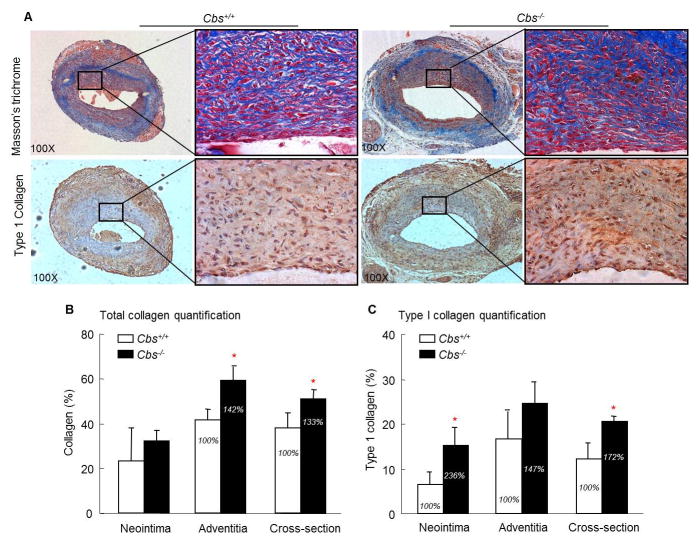

4.3 HHcy increases collagen deposition in the lesion in Cbs−/− mice

We analyzed total collagen levels in the vein graft by Masson’s trichrome staining and found that collagen deposition is largely increased in in Cbs−/− mice (Figure 3A). The adventitial area of the vein graft adjacent to the elastic lamina stained strongly for collagen (Fig 3A). Total collagen content, expressed as a percentage of the section area, is significantly increased in the adventitial area in Cbs−/− mice compared with that in Cbs+/+ mice (59.39±5.77% versus 41.72±4.77%, p<0.05), as well as in the whole vessel cross-section (50.92±4.27% versus 38.15±6.70%, p<0.05) (Figure 3B). Type 1 collagen content is notably increased in the neointimal area in Cbs−/− mice than in Cbs+/+ mice (15.33±3.74% versus 6.50±2.73%, p<0.05), and in the whole vessel cross-section (19.94±0.84% versus 11.62±4.38%, p<0.05) (Fig 3C).

Figure 3. Severe HHcy increases total collagen and type 1 collage in the neointima in the vein graft in Cbs−/− mice.

The mouse vein graft surgery procedure was performed on Cbs mice at the age of 12 weeks as described in Figure 1 and in the section of Methods. The grafts, together with a short segment of the native carotid artery, were harvested at 4 weeks after surgery by cutting at the center of the graft. One portion was processed for paraffin embedding and the other for cryostat sectioning. A. Photomicrographs of collagen staining. Paraffin-embedded cross sections of the vein graft stained for total collagen by Masson’s trichrome method and cryostat sections immunostained with antibody against type 1 collagen. Collagen shows as blue and type 1 collagen as brown. B&C. Total collagen and type 1 collagen quantification. Total collagen and type 1 collagen area were analyzed by computerized planimetry. Notice that total collagen deposition is increased in the adventitia, and type 1 collagen deposition is increased in the neointima in Cbs−/− mice. Values represent mean±SEM, n=9, p values from independent t test * p<0.05 versus Cbs+/+ group.

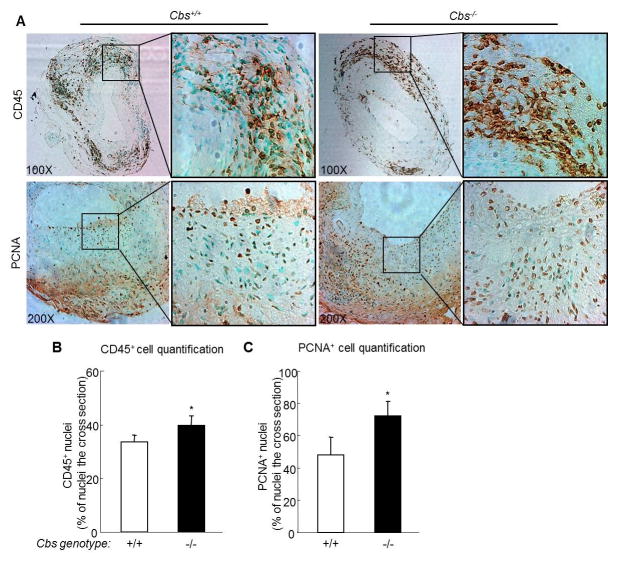

4.4 HHcy increases CD45+ monocyte in the lesion in Cbs−/− mice

We observed CD45-positive (CD45+) leukocyte infiltration in the neointima, but more abundant infiltration in the adventitial area of the vein graft (Figure 4A). Leukocyte infiltration is more prominent in the venous portion of the composite vessel. HHcy increased CD45+ cells in the adventitia of vein graft in Cbs−/− mice 39.07±4.10% compared with 30.80±4.76% in Cbs+/+ mice (p<0.05, Figure 4B).

Figure 4. Severe HHcy increases CD45 positive cells and proliferative cells in cross section of vein graft in Cbs−/− mice.

The mouse vein graft surgery procedure was performed on Cbs mice at the age of 12 weeks as described in Figure 1 and in the section of Methods. The grafts, together with a short segment of the native carotid artery, were harvested at 4 weeks after surgery by cutting at the centre of the graft. One portion was processed for paraffin embedding and the other for cryostat sectioning. A. Photomicrographs of infiltrated leukocyte and proliferative cells. Cryostat sections were stained with antibodies against mouse CD45, a common antigen of leukocyte and anti-proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA), marker of proliferative cells. CD45 positive nuclei and proliferative cell nuclei were showed as dark brown. B. Quantitative analysis of CD45 positive nuclei. C. Quantitative analysis of PCNA positive nuclei. CD45 and PCNA positive nuclei were analyzed using a computer program. The percentage of positive nuclei was calculated as 100x [positive nuclei ÷ (positive nuclei + negative nuclei)] in the cross section. HHcy significantly increased the ratio of CD45 positive cells and of PCNA positive cells in the cross section. Values represent mean±SEM, n=9, p values from independent t test * p<0.05 versus Cbs+/+ group.

4.5 HHcy increases the number of proliferating cells in the lesions in Cbs−/− mice

We found a high content of PCNA-positive cells, a marker of cellular proliferation, in the neointima and adventitia of the vein graft (Figure 4A and B). PCNA positive proliferating cells are significantly increased in the whole vessel cross-section in Cbs−/− mice compared to that in Cbs+/+ mice (69.56±8.54% versus 47.41±21.64%, p<0.05, Figure 5C).

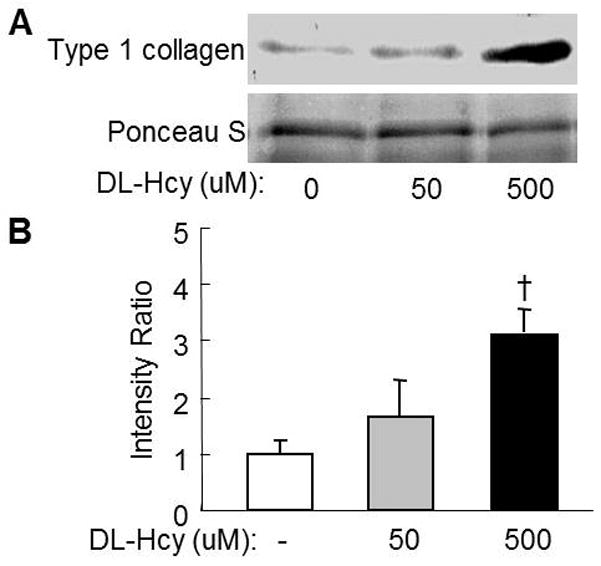

Figure 5. Hcy increases collagen secretion in cultured rat aortic smooth muscle cells (RASMC).

Confluent RASMC at passage 6th were cultured in M199 medium with 10% CS and treated DL-Hcy at indicated concentrations for additional 3 weeks. Supernatant was collected and used for Western blotting analysis with rabbit anti-rat type 1 collagen monoclonal antibody. A. Representative blot. B. Quantitative analysis of type 1 collagen. Data are representative of 3 independent experiments, and expressed as mean±SEM, † p<0.05 versus no Hcy control.

4.6 Hcy stimulates collagen 1 secretion in RASMC

We reproduced HHcy–induced type 1 collagen expression in cultured RASMC and found that DL-Hcy induced type collagen 1 secretion in a dose sensitive manner. DL-Hcy, at the concentration of 50μmol/L, increased the levels of secreted type 1 collagen 157% compared with the control group. 500 μmol/L DL-Hcy increased type 1 collagen 309% in cultured RASMC (Figure 5).

5. DISCUSSION

Mechanical injury is a significant cause of atherosclerosis. The most frequently occurring post-injury pathology in the vessel wall is restenosis of the coronary artery following angioplasty or bypass surgery, which is a major cause of morbidity and mortality in cardiovascular patients19, 20. Vein grafts are the major conduits for bypass surgery in patients with coronary or peripheral arterial diseases. However, about 20% of vein grafts develop partial or total obstructions or restenosis within 5 years of the bypass surgery due to post-injury atherosclerosis or vascular remodeling.21 In this study, in order to evaluate the effect of HHcy on intimal hyperplasia and vascular remodeling post vein graft bypass surgery, we used a carotid arterial vein graft model. The carotid arterial vein graft model is preferable because it mimics human coronary angioplasty procedures, does not involve immune rejection, and is highly clinically relevant. This surgical model is a valuable tool for investigating the effects and mechanisms of cardiovascular disease risk factors on post-injury atherosclerosis and vascular remodeling.

We previously reported that high methionine diet-induced HHcy impairs reendothelialization and promotes neointima formation post-endothelial injury using a carotid artery air-dry endothelial denudation model17. The air-dry endothelial denudation model introduces consistent endothelial injury without medial wall damage and is the ideal model to examine endothelial phenotype and consequential vascular remodeling post endothelial injury. In the present study, we evaluated HHcy’s on vascular remodeling in a vein graft model, which emphasizes VSMC phenotype and mimics angioplasty procedures.

The current study demonstrated that severe HHcy promoted post-injury neointima formation and led to luminal narrowing in bypass vein grafts. Atherosclerosis is characterized by extensive thickening of the arterial intima that is associated both with vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC) proliferation and excessive deposition of the extracellular matrix (ECM) protein by intimal VSMC22, 23. Moderate HHcy is associated with an increased incidence of carotid artery stenosis in humans2. Our previous study demonstrated that Hcy promotes vascular SMC proliferation in cultured human and rat VSMC 9. Here, we confirmed that most of the newly formed neointima stains positive for α-SMA, a typical smooth muscle cell phenotype. We also found that many of the neointimal cells are stained by the anti-PCNA antibody, indicating active proliferation of VSMC in the neointima. Therefore Hcy promotes vascular SMC proliferation, which may contribute to the vein graft neointima formation.

The ECM is composed of vastly different macromolecules such as collagen, elastin, glycoproteins and proteoglycans24, 25, which provides structural support and scaffolds to stabilize vasculature. Each component of the ECM possesses unique structural properties and participates in several key events such as cell migration, cell proliferation, lipoprotein retention, and thrombosis26. Excessive deposition of ECM protein in the vessel wall contributes to vessel wall thickness and stiffness, leading to hypertension and atherosclerosis. Several lines of evidence suggest that HHcy may alter vascular matrix structure27, 28. In the present study, we found that HHcy induced a fibrotic-intensive vascular remodeling because elastin increased by 131% in the neointima and induced total collagen increased by 142% in the adventitia and 133% in the whole cross section of the vein graft in Cbs−/− mice. We also found that the neointima area of the vein graft exhibits severe elastin disorder. The fragmented deposits of elastin and loosely arranged collagen bundles were usually more prominent in the mid to deep musculoelastic layer than in the subendothelial zone. This is consistent with McCully’s first report that the accumulation of collagen in atherosclerotic plaques in children with premature atherosclerosis resulted from severe HHcy29. Previous studies also reported that HHcy increased collagen accumulation in the carotid artery of mice and rats27, 30. It is known that collagen is a major component of atherosclerotic plaques, which makes up about 60% of the total protein in the lession27, 31. Collagen fibers can occupy about 80% of the section area in the samples of human coronary restenotic lesions32. Because type 1 collagen may account for 70% of all collagen in plaques33, we examined type 1 collagen content by immunohistochemistry staining and found that type 1 collagen is increased by 136% in the neointima and by 72% in the whole cross section of the vein graft in Cbs−/− mice. We also examined the effect of Hcy on type 1 collagen production in cultured RASMC. We reproduced our in vivo finding and found that Hcy can induce collagen secretion in a dose-sensitive manner, and that 500 μM Hcy increased type 1 collagen secretion by 189.56%. Hcy induced vascular fibrosis, as evidenced by increased collagen and elastin deposition may lead to decreased vessel wall elasticity and increased vascular remodeling. Uncontrolled collagen and elastin accumulation leads to arterial stenosis and vessel wall stiffness, which can result in an advanced pathophysiological progression of the cardiovascular disease.

Moreover, we found HHcy increased the recruitment of CD45 positive leukocytes in the adventitia, particularly in the venous portion of the composite vessel. Many of the adventitial cells are also PCNA positive, suggesting an active proliferation of leukocytes in the adventitia. These results suggest HHcy may augment an inflammatory response following vein graft injury and consequently contribute to the development of arteriosclerosis.

In summary, we reported here that severe HHcy increases neointima formation and vascular fibrosis in bypass vein grafts. We postulated that HHcy stimulates VSMC proliferation and collagen I production, inducing fibrosis and a decrease of elasticity, leading to arterial remodeling and vascular resistance. Our results support a cellular mechanism for vein graft-related atherogenesis in HHcy and provide insight into a potential preventive treatment.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NIH Grants HL67033, HL77288, HL82774, HL110764 and HL117654 (HW); and HL9445, HL108910 and HL116917 (XFY); and China NSFC grant 81370371(HMT).

References

- 1.Clarke R, Daly L, Robinson K, Naughten E, Cahalane S, Fowler B, Graham I. Hyperhomocysteinemia: an independent risk factor for vascular disease. N Engl J Med. 1991;324(17):1149–1155. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199104253241701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nygard O, Nordrehaug JE, Refsum H, Ueland PM, Farstad M, Vollset SE. Plasma homocysteine levels and mortality in patients with coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 1997;337(4):230–236. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199707243370403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng Z, Jiang X, Kruger WD, Pratico D, Gupta S, Mallilankaraman K, Madesh M, Schafer AI, Durante W, Yang X, Wang H. Hyperhomocysteinemia impairs endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor-mediated vasorelaxation in transgenic cystathionine beta synthase-deficient mice. Blood. 2011;118(7):1998–2006. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-333310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jiang X, Yang F, Tan H, Liao D, Bryan RM, Jr, Randhawa JK, Rumbaut RE, Durante W, Schafer AI, Yang X, Wang H. Hyperhomocystinemia impairs endothelial function and eNOS activity via PKC activation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25(12):2515–2521. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000189559.87328.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Woo CW, Siow YL, Pierce GN, Choy PC, Minuk GY, Mymin D, OK Hyperhomocysteinemia induces hepatic cholesterol biosynthesis and lipid accumulation via activation of transcription factors. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2005;288(5):E1002–1010. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00518.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liao D, Tan H, Hui R, Li Z, Jiang X, Gaubatz J, Yang F, Durante W, Chan L, Schafer AI, Pownall HJ, Yang X, Wang H. Hyperhomocysteinemia decreases circulating high-density lipoprotein by inhibiting apolipoprotein A-I Protein synthesis and enhancing HDL cholesterol clearance. Circ Res. 2006;99(6):598–606. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000242559.42077.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Riba R, Nicolaou A, Troxler M, Homer-Vaniasinkam S, Naseem KM. Altered platelet reactivity in peripheral vascular disease complicated with elevated plasma homocysteine levels. Atherosclerosis. 2004;175(1):69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ebbesen LS. Hyperhomocysteinemia, thrombosis and vascular biology. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand) 2004;50(8):917–930. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsai JC, Wang H, Perrella MA, Yoshizumi M, Sibinga NE, Tan LC, Haber E, Chang TH, Schlegel R, Lee ME. Induction of cyclin A gene expression by homocysteine in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Clin Invest. 1996;97(1):146–153. doi: 10.1172/JCI118383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu X, Shen J, Zhan R, Wang X, Zhang Z, Leng X, Yang Z, Qian L. Proteomic analysis of homocysteine induced proliferation of cultured neonatal rat vascular smooth muscle cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1794(2):177–184. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bhargava B, Karthikeyan G, Abizaid AS, Mehran R. New approaches to preventing restenosis. BMJ. 2003;327(7409):274–279. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7409.274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weintraub WS. The pathophysiology and burden of restenosis. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100(5A):3K–9K. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inoue T, Node K. Molecular basis of restenosis and novel issues of drug-eluting stents. Circ J. 2009;73(4):615–621. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-09-0059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Windecker S, Meier B. Late coronary stent thrombosis. Circulation. 2007;116(17):1952–1965. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.683995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rasmussen LM, Hansen PR, Ledet T. Homocysteine and the production of collagens, proliferation and apoptosis in human arterial smooth muscle cells. APMIS. 2004;112(9):598–604. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2004.apm1120907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhou J, Moller J, Danielsen CC, Bentzon J, Ravn HB, Austin RC, Falk E. Dietary supplementation with methionine and homocysteine promotes early atherosclerosis but not plaque rupture in ApoE-deficient mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2001;21(9):1470–1476. doi: 10.1161/hq0901.096582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tan H, Jiang X, Yang F, Li Z, Liao D, Trial J, Magera MJ, Durante W, Yang X, Wang H. Hyperhomocysteinemia inhibits post-injury reendothelialization in mice. Cardiovasc Res. 2006;69(1):253–262. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shi C, Patel A, Zhang D, Wang H, Carmeliet P, Reed GL, Lee ME, Haber E, Sibinga NE. Plasminogen is not required for neointima formation in a mouse model of vein graft stenosis. Circ Res. 1999;84(8):883–890. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.8.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Douglas JS., Jr Pharmacologic approaches to restenosis prevention. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100(5A):10K–16K. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kiernan TJ, Yan BP, Cruz-Gonzalez I, Cubeddu RJ, Caldera A, Kiernan GD, Gupta V. Pharmacological and cellular therapies to prevent restenosis after percutaneous transluminal angioplasty and stenting. Cardiovasc Hematol Agents Med Chem. 2008;6(2):116–124. doi: 10.2174/187152508783955033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lichtenwalter C, de Lemos JA, Roesle M, Obel O, Holper EM, Haagen D, Saeed B, Iturbe JM, Shunk K, Bissett JK, Sachdeva R, Voudris VV, Karyofillis P, Kar B, Rossen J, Fasseas P, Berger P, Banerjee S, Brilakis ES. Clinical presentation and angiographic characteristics of saphenous vein graft failure after stenting: insights from the SOS (stenting of saphenous vein grafts) trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2009;2(9):855–860. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2009.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Merrilees MJ, Beaumont BW, Braun KR, Thomas AC, Kang I, Hinek A, Passi A, Wight TN. Neointima formed by arterial smooth muscle cells expressing versican variant V3 is resistant to lipid and macrophage accumulation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31(6):1309–1316. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.225573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lacolley P, Regnault V, Nicoletti A, Li Z, Michel JB. The vascular smooth muscle cell in arterial pathology: a cell that can take on multiple roles. Cardiovasc Res. 2012;95(2):194–204. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garcia-Touchard A, Henry TD, Sangiorgi G, Spagnoli LG, Mauriello A, Conover C, Schwartz RS. Extracellular proteases in atherosclerosis and restenosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25(6):1119–1127. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000164311.48592.da. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wight TN, Merrilees MJ. Proteoglycans in atherosclerosis and restenosis: key roles for versican. Circ Res. 2004;94(9):1158–1167. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000126921.29919.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katsuda S, Kaji T. Atherosclerosis and extracellular matrix. J Atheroscler Thromb. 2003;10(5):267–274. doi: 10.5551/jat.10.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kumar M, Tyagi N, Moshal KS, Sen U, Kundu S, Mishra PK, Givvimani S, Tyagi SC. Homocysteine decreases blood flow to the brain due to vascular resistance in carotid artery. Neurochem Int. 2008;53(6–8):214–219. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumar M, Tyagi N, Moshal KS, Sen U, Pushpakumar SB, Vacek T, Lominadze D, Tyagi SC. GABAA receptor agonist mitigates homocysteine-induced cerebrovascular remodeling in knockout mice. Brain Res. 2008;1221:147–153. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCully KS. Vascular pathology of homocysteinemia: implications for the pathogenesis of arteriosclerosis. Am J Pathol. 1969;56(1):111–128. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guo YH, Chen FY, Wang GS, Chen L, Gao W. Diet-induced hyperhomocysteinemia exacerbates vascular reverse remodeling of balloon-injured arteries in rat. Chin Med J (Engl) 2008;121(22):2265–2271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stary HC, Chandler AB, Dinsmore RE, Fuster V, Glagov S, Insull W, Jr, Rosenfeld ME, Schwartz CJ, Wagner WD, Wissler RW. A definition of advanced types of atherosclerotic lesions and a histological classification of atherosclerosis. A report from the Committee on Vascular Lesions of the Council on Arteriosclerosis, American Heart Association. Circulation. 1995;92(5):1355–1374. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.5.1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pickering JG, Ford CM, Chow LH. Evidence for rapid accumulation and persistently disordered architecture of fibrillar collagen in human coronary restenosis lesions. Am J Cardiol. 1996;78(6):633–637. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(96)00384-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Katsuda S, Okada Y, Minamoto T, Oda Y, Matsui Y, Nakanishi I. Collagens in human atherosclerosis. Immunohistochemical analysis using collagen type-specific antibodies. Arterioscler Thromb. 1992;12(4):494–502. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.12.4.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]