Abstract

Purpose

Effectively identifying the proteins present in the cellular secretome is complicated due to the presence of cellular protein leakage and serum protein supplements in culture media. A metabolic labeling and click chemistry capture method is described that facilitates the detection of lower abundance glycoproteins in the secretome, even in the presence of serum.

Experimental design

Two stromal cell lines were incubated with tetraacetylated sugar-azide analogs for 48 h in serum-free and low-serum conditions. Sugar-azide labeled glycoproteins were covalently linked to alkyne-beads, followed by on-bead trypsin digestion and MS/MS. The resulting glycoproteins were compared between media conditions, cell lines, and azide-sugar labels.

Results

Alkyne-bead capture of sugar-azide modified glycoproteins in stromal cell culture media significantly improved the detection of lower abundance secreted glycoproteins compared to standard serum-free secretome preparations. Over 100 secreted glycoproteins were detected in each stromal cell line and significantly enriched relative to a standard secretome preparation.

Conclusion and clinical relevance

Sugar-azide metabolic labeling is an effective way to enrich for secreted glycoproteins present in cell line secretomes, even in culture media supplemented with serum. The method has utility for identifying secreted stromal proteins associated with cancer progression and the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition.

Keywords: Glycoproteins, Metabolic labeling, Prostate cancer, Secretome, Stroma

The secretome represents the proteins secreted or shed into culture media by a cell line or in vivo into proximal fluids by tissues [1, 2]. These proteins are frequently glycosylated and are involved in cellular communication, recognition, and growth regulation processes. In relation to cancer research, the proteins secreted by tumor cells and tumor-associated stroma are a rich source of potential diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets [3, 4]. The proteomic analysis of secreted proteins can be challenging due to low protein concentrations in proximal fluids or culture media as well as the presence of more abundant cytoplasmic or structural proteins due to cell lysis or added FBS proteins [1, 2]. Minimizing FBS protein contamination is controlled by doing incubations with serum-free media for collection of secreted cellular proteins. However, the lack of serum can cause increased cell death and lysis, confounding analysis and differentiation of truly secreted proteins [1, 2]. Enrichment methods for specific isolation of glycoproteins in complex mixtures prior to MS analysis has focused primarily on the use of lectin, titanium oxide, or hydrazide columns [5–10]. For secretome analysis, the presence of serum in the media precludes use of these methods. An alternative approach is to use azido-sugar analogs of sialic acid (tetraacetylated N-azidoacetyl-d-mannosamine; ManNAcAz) or N-acetylgalactosamine (tetraacetylated N-azidoacetyl-d-N-acetylgalactosamine; GalNAcAz) for metabolic labeling of growing cells [11–15]. For each sugar, the method utilizes the native cellular biosynthetic pathways for the incorporation of monosaccarides bearing a bio-orthogonal functional handle (i.e., an azide) that can be stably and rapidly conjugated with alkyne compounds (i.e., Click chemistry) [11–15].

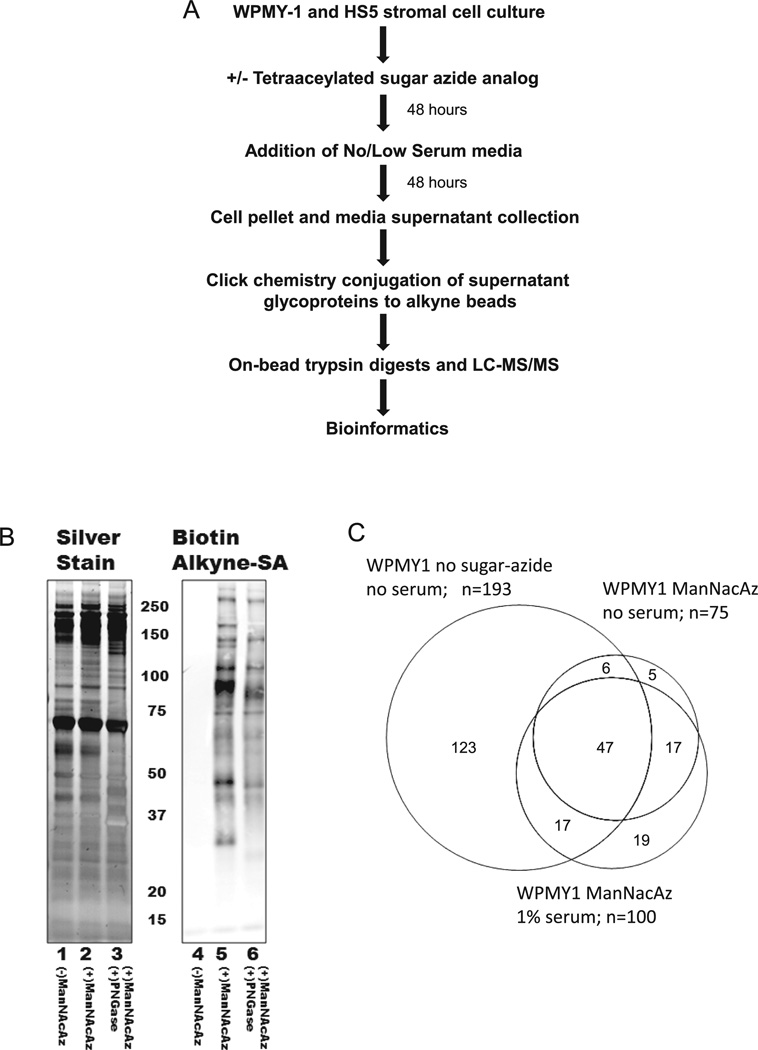

We hypothesized that use of the sugar-azide label could offer specific detection of low abundance secreted glycoproteins in complex media preparations, even in the presence of serum supplements. To determine the efficacy of the azide-sugar affinity capture approach, a series of comparative secretome experiments were devised using WPMY-1 prostate stromal cells. The first study evaluated the number of glycoproteins that were detected using the ManNAcAz label in serum-free or low-serum media conditions, in comparison to proteins detected in standard serum-free media conditions. The experimental workflow is summarized in Fig. 1A, and further experimental details are provided in the Supporting Information. Proteins in conditioned serum-free media without sugar-azide treatment were concentrated by filtration and separated on SDS-gels, followed by in-gel trypsin digests of the gel slices and MS/MS identification. The ManNAcAz-treated media were concentrated by filtration, incubated with commercially available alkyne-agarose beads or biotin-alkyne (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and subjected to copper-catalyzed click chemistry reactions. As shown in Fig. 1B (lane 5), ManNAcAz-treated media conjugated with biotin-alkyne and blotted for streptavidin binding contained an abundant number of proteins that incorporated the analog. No proteins were detected in the control conditioned media lacking sugar-azide. Further, to demonstrate N-linked glycan incorporation of ManNAcAz, treatment of media proteins with protein N-glycanase F (PNGaseF) prior to biotin-alkyne detection (Fig. 1B, lane 6) indicated a marked decrease in streptavidin binding of multiple protein bands, with expected migration shifts due to glycan loss (Fig. 1B, lane 3 and lane 6).

Figure 1.

Secretome analysis using sugarazide metabolic labels. (A) Summary of the experimental workflow. (B) Conditioned media from WPMY1 cells grown 48 h with and without tetraacetylated N-azidoacetyl-d-mannosamine (ManNAcAz) were collected and reacted with biotin-alkyne. A portion of the ManNAcAz proteins were also treated with protein N-glycanase. Proteins from each condition were loaded in replicate and separated on the same SDS-gel. One half of the gel was silver stained (lanes 1–3), and the other half was blotted to nitrocellulose for detection with an IR800 streptavidin antibody (lanes 4–6). The samples treated with protein N-glycanase are in lanes 3 and 6. (C) Venn diagram comparison of the secretome proteins detected in the serum-free WPMY1 cells with no ManNAcAz, serum-free WPMY1 media from cells treated with ManNAcAz, and 1% serum WPMY1 media from cells treated with ManNAcAz.

For detection of bound glycoproteins to the alkyne-beads, glycoproteins were directly trypsinized on the beads, and the resulting peptides were submitted for MS/MS analysis. For comparison, the top 20 most abundant proteins detected in the nonsugar-azide treated serum-free media versus the ManNAcAz-labeled media are listed in Table 1, and the total numbers detected summarized in the Venn diagram in Fig. 1C. The entire protein lists for each condition are provided in Supporting Information Table 1. Using the Uniprot keyword classification for glycoproteins, a sublist of total glycoproteins detected in each sample is listed in Supporting Information Table 2.

Table 1.

Most abundant proteins in serum-free media of WPMY1 cells, plus or minus ManNAcAz treatment

| Most abundant proteins | Normalized spectral counts |

WPMY1 | Glycoprotein |

|---|---|---|---|

| WPMY1 no sugar-azide, no serum | |||

| Fibronectin | 27.83 | 124.95 | Yes |

| Collagen alpha-1(XII) chain | 15.25 | 10.76 | Yes |

| Alpha-actinin-4 | 12.98 | 0.00 | No |

| Alpha-enolase | 12.90 | 0.00 | No |

| Collagen alpha-2(I) chain | 11.72 | 50.14 | Yes |

| Pyruvate kinase isozymes M1/M2 | 10.94 | 0.00 | No |

| Collagen alpha-1(I) chain | 9.95 | 11.67 | Yes |

| Filamin-A | 9.72 | 0.00 | No |

| Collagen alpha-1(VI) chain | 9.72 | 31.15 | Yes |

| Alpha-actinin-1 | 8.84 | 0.00 | No |

| Heat shock cognate 71 kDa protein | 8.53 | 0.00 | No |

| HSP 90-alpha | 7.86 | 0.00 | No |

| Filamin-C | 7.75 | 0.00 | No |

| Isoform 2of calsyntenin-1 | 7.70 | 45.78 | Yes |

| HSP 90-beta | 7.45 | 0.00 | Yes |

| L-lactate dehydrogenase A chain | 7.29 | 0.00 | No |

| Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase A | 6.56 | 0.00 | No |

| Sulfhydryl oxidase 1 | 6.56 | 37.80 | Yes |

| Vinculin | 6.21 | 0.00 | No |

| Plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 | 6.20 | 19.47 | Yes |

| WPMY1 ManNAcAz, no serum | |||

| Fibronectin | 124.95 | 27.83 | Yes |

| Collagen alpha-2(I) chain | 50.14 | 11.72 | Yes |

| Follistatin-related protein 1 | 47.41 | 2.12 | Yes |

| Isoform 2of calsyntenin-1 | 45.78 | 7.70 | Yes |

| Galectin-3-binding protein | 44.63 | 5.11 | Yes |

| SPARC | 38.70 | 3.72 | Yes |

| Sulfhydryl oxidase 1 | 37.80 | 6.56 | Yes |

| Collagen alpha-1(VI) chain | 31.15 | 9.72 | Yes |

| Metalloproteinase inhibitor 1 | 29.76 | 1.24 | Yes |

| Pentraxin-related protein PTX3 | 26.55 | 4.76 | Yes |

| CD166 antigen | 23.64 | 0.00 | Yes |

| Dystroglycan | 22.20 | 0.00 | Yes |

| Complement C1r subcomponent | 20.38 | 1.91 | Yes |

| Plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 | 19.47 | 6.20 | Yes |

| 72 kDa type IV collagenase | 17.18 | 2.48 | Yes |

| Extracellular matrix protein 1 | 16.51 | 1.45 | Yes |

| CD44 antigen | 15.60 | 0.21 | Yes |

| Heparan sulfate proteoglycan | 15.12 | 3.03 | Yes |

| Cadherin-2 | 14.88 | 0.00 | Yes |

| Laminin subunit gamma-1 | 14.45 | 0.93 | Yes |

As is evident in the comparison in Table 1, there is a significant enrichment in glycoproteins in the azide-sugar treated samples. In the standard serum-free media approach, 11 of the top 20 proteins were not glycoproteins and represented common metabolic and structural proteins. The ManNAcAz-captured glycoproteins were significantly enriched, and the same metabolic proteins were not detected. The inclusion of 1% serum in the media during the 48 h collection period following labeling was also effective, and may have improved results as far as in the number of additional glycoproteins detected. Additionally, the inclusion of 1% serum maintained overall cell viability during this 2 day period as compared to the serum-free media condition, which had more detached and dying cells present (data not shown). For further comparison, the WPMY-1 cells were treated with GalNAcAz identically as described for ManNAcAz in 1% serum and conditioned media was processed for glycoprotein capture. Another cell line, HS5 bone marrow stromal cells, were also grown in the presence of GalNAcAz and ManNAcAz, and similarly processed. The resulting glycoproteins identified are listed in both Supporting Information Table 1 for total protein, and Supporting Information Table 2 for glycoproteins labeled with ManNAcAz. The implemented method was particularly useful for enriching detection of metalloproteinases (MMP1,MMP2, MMP3) and other known modulators of extracellular matrix activity like TIMP1,N-cadherin/cadherin-2, SPARC, and dystroglycan. Venn diagram comparisons of the GalNAcAz- and ManNAcAz-labeled glycoproteins detected for each cell line, and comparisons between both cell lines, are provided in Supporting Information Fig. 1. Notably, there are many shared glycoproteins in the lists, and use of the GalNAcAz label increases the number of cell adhesion type proteins detected. Distinct glycoproteins identified in the HS5 secretome as compared with the WPMY1 secretome include interleukin 6 and thrombospondin, both of which are involved in angiogenesis, cancer, and inflammation. The differences noted for the glycoproteins detected in the two stromal cell lines would be expected due to their prostate and bone marrow origins (Supporting Information Fig. 1B). The combined use of both labels provides a more comprehensive profile of the secretome glycoproteins present in each cell line.

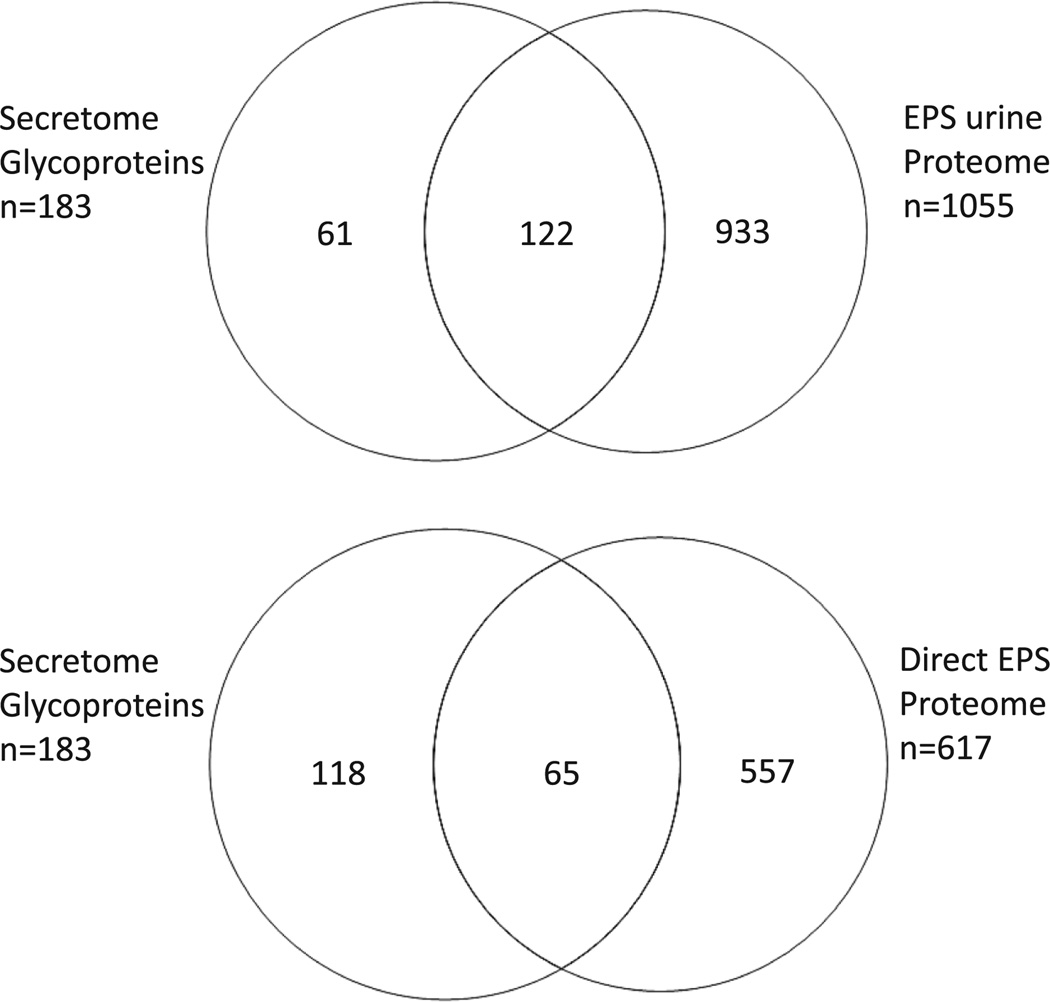

Because prostate tumor cells frequently metastasize to the bone, the combined glycoproteins from these two cell lines were cross-referenced to two prostatic fluid proteomes derived from prostatic secretions in urine obtained at the time of biopsy [16], and prostatic fluids obtained at the time of prostatectomy [17]. In Fig. 2, a Venn diagram comparison of the number of glycoproteins from the cell lines that are also present in the proteomes of the two prostatic fluids is illustrated. The protein identities that are shared in both secretome media and prostatic fluids are provided in Supporting Information Table 3.

Figure 2.

Venn diagram comparisons of WPMY1and HS5 stromal cell secretomes following ManNAcAz and GalNAcAz treatments with expressed prostatic secretion proteomes. The cumulative secretome glycoproteins from both cell lines and both sugarazide labels listed in Supporting Information Table 1 were combined for comparison of shared expression with the proteomes from clinical prostatic fluids, expressed prostatic secretions (EPS) in urine [16], and direct EPS obtained at the time of prostatectomy [17]. Keratins were excluded from the comparison.

In summary, the sugar-azide metabolic labeling workflow is an effective way to enrich for secreted glycoproteins present in cell line secretomes, even in culture media supplemented with serum. The method uses commercially available reagents and is readily adaptable to any cultured cell system. For the two cell lines evaluated herein, our approach has utility for identifying bioactive stromal proteins associated with prostate cancer and the epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, and those present in human prostatic fluids [16, 17]. The covalent attachment of the sugars to the alkyne beads clearly facilitates improved detection of glycoproteins, and minimal detection of nonglycosylated proteins. Peptide sequencing of the N-linked and O-linked peptides still bound to the alkyne-beads that can be released by enzymatic digestion or beta elimination is ongoing. As presented, the major disadvantage of the method is that it will only label proteins that have sialic acid or GalNAc modifications, therefore it is not comprehensive. It also does not reflect relative abundance of the total amount of a particular protein present, as it is probable that there may be a proportion of a given glycoprotein that could lack the modification depending on the conditions. Incorporation of SILAC labeling into the workflow and analysis on higher resolution mass spectrometers has the potential to overcome the quantitative limitation, and it is an excellent approach for identifying candidates for further analysis by Western blot or ELISA. This research is ongoing for these stromal cells and other cell models being evaluated in the lab.

Supplementary Material

Clinical Relevance.

The tumor microenvironment, or stroma, is composed of fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and inflammatory cells that secrete factors that promote tumorigenesis, progression, and metastasis of epithelial cells. The stroma initiates the formation of a metastatic niche for cell recruitment suggesting a crucial role for secretory products released into circulation, which correlates with more lethal prostate cancer outcomes. For prostate cancer, the stromal microenvironment is thought to enhance the metastatic potential of prostate epithelial cells, leading to the development of metastasis to primarily bones. In turn, there are stromal factors in the bone that facilitate growth of prostate cancer cells in this niche. Further understanding of the complexities of factors mediating stromal-epithelial communication may yield novel therapeutic targets for prostate cancer, particularly targets that would prevent migration and growth of tumor cells in the bone. The goal of our experimental strategy is to provide a more comprehensive definition of the secreted protein factors from prostate and bone stromal cell lines. This definition of stromal secreted proteins could identify potential cancer biomarker candidates and allow the targeting of the tumor microenvironment for development of more effective cancer therapies.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute grants R21CA137704 and R01CA135087, and the state of South Carolina SmartState Endowed Research program to R.R.D, and an American Cancer Society Institutional Research Grant #IRG-97-219-11 to M.Z.

Abbreviations

- GalNAc

N-acetylgalactosamine

- GalNAcAz

tetraacetylated N-azidoacetyl-d-N-acetylgalactosamine

- ManNAcAz

tetraacetylated N-azidoacetyl-d-mannosamine

Footnotes

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher’s web-site

The authors have declared no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Makridakis M, Vlahou A. Secretome proteomics for discovery of cancer biomarkers. J. Proteomics. 2010;73:2291–2305. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown KJ, Formolo CA, Seol H, Marathi RL, et al. Advances in the proteomic investigation of the cell secretome. Expert Rev. Proteomics. 2012;9:337–345. doi: 10.1586/epr.12.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kulasingam V, Diamandis EP. Strategies for discoveringnovel cancer biomarkers through utilization of emerging technologies. Nat. Clin. Pract. Oncol. 2008;5:588–699. doi: 10.1038/ncponc1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.May M. From cells, secrets of the secretome leak out. Nat. Med. 2009;15:828. doi: 10.1038/nm0809-828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drake RR, Schwegler EE, Malik G, Diaz J, et al. Lectin capture strategies combined withmass spectrometry for the discovery of serum glycoprotein biomarkers. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2006;5:1957–1967. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M600176-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Madera M, Mechref Y, Novotny MV. Combining lectin microcolumns with high-resolution separation techniques for enrichment of glycoproteins and glycopeptides. Anal. Chem. 2005;77:4081–4090. doi: 10.1021/ac050222l. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang Z, Hancock WS. Monitoring glycosylation pattern changes of glycoproteins using multi-lectin affinity chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A. 2005;1070:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2005.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Larsen MR, Jensen SS, Jakobsen LA, Heegaard NH. Exploring the sialiome using titanium dioxide chromatography and mass spectrometry. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2007;6:1778–1787. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700086-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang H, Li XJ, Martin DB, Aebersold R. Identification and quantification of N-linked glycoproteins using hydrazide chemistry, stable isotope labeling and mass spectrometry. Nat. Biotechnol. 2003;21:660–666. doi: 10.1038/nbt827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang H, Yi EC, Li XJ, Mallick P, et al. High throughput quantitative analysis of serum proteins using glycopeptide capture and liquid chromatography mass spectrometry. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2005;4:144–155. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M400090-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang L, Nyalwidhe JO, Guo S, Drake RR, et al. Targeted identification of metastasis-associated cell-surface sialoglycoproteins in prostate cancer. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2011;10 doi: 10.1074/mcp.M110.007294. M110.007294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laughlin ST, Agard NJ, Baskin JM, Carrico IS, et al. Metabolic labeling of glycans with azido sugars for visualization and glycoproteomics. Methods Enzymol. 2006;415:230–250. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)15015-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dube DH, Prescher JA, Quang CN, Bertozzi CR. Probing mucin-type O-linked glycosylation in living animals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:4819–4824. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506855103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Laughlin ST, Bertozzi CR. Imaging the glycome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:12–17. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811481106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boyce M, Carrico IS, Ganguli AS, Yu SH, et al. Metabolic cross-talk allows labeling of O-linked beta-N-acetylglucosamine-modified proteins via the N-acetylgalactosamine salvage pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:3141–3146. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1010045108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Principe S, Kim Y, Fontana S, Ignatchenko V, et al. Identification of prostate-enriched proteins by in-depth proteomic analyses of expressed prostatic secretions in urine. J. Proteome Res. 2012;11:2386–2396. doi: 10.1021/pr2011236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim Y, Ignatchenko V, Yao CQ, Kalatskaya I, et al. Identification of Differentially Expressed Proteins in Direct Expressed Prostatic Secretions of Men with Organ-confined Versus Extracapsular Prostate Cancer. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2012;11:1870–1884. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M112.017889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.