Abstract

Compared to non-Latino Whites, US racial/ethnic minority groups show higher non-adherence with outpatient antidepressant therapy, including lower retention, despite adjusting for sociodemographic and insurance covariates. Culturally salient concerns about antidepressants leading to ambivalence about treatment engagement may contribute to this discrepancy. To improve treatment adherence among depressed Latinos, we developed Motivational Pharmacotherapy, a novel approach that combines Motivational Interviewing, standard pharmacotherapy, and attention to Latino cultural concerns about antidepressants. This 12-week, open-trial, pre-post pilot study assessed the impact of Motivational Pharmacotherapy on antidepressant therapy retention, response (symptoms, functioning, and quality of life), and visit duration among N=50 first-generation Latino outpatients with Major Depressive Disorder. At study endpoint, 20% of patients discontinued treatment, with a mean therapy duration of 74.2 out of 84 days. Patients’ symptoms, psychosocial functioning, and quality of life improved significantly. Mean visit length was 36.7 minutes for visit 1 and 24.3 minutes for subsequent visits, compatible with use in community clinics. Responder and remitter rates were 82% and 68%. Compared to published Latino proportions of non-retention (32-53%) and previous studies at our clinic with similar samples and medications (36-46%), Motivational Pharmacotherapy appears to improve Latino retention in antidepressant therapy, and should be investigated further in controlled designs.

Compared to non-Latino Whites, underserved racial/ethnic groups in the United States typically show higher non-adherence to antidepressant therapy, as evidenced by lower rates of initiation, retention, and medication taking (Harman, Edlund, & Fortney, 2004; Lanouette, Folsom, Sciolla, & Jeste, 2009; Olfson, Marcus, Tedeschi, & Wan, 2006; Sleath, Rubin, & Huston, 2003; Warden, et al., 2007). Likely reasons for this non-adherence include healthcare system-level and provider-level disparities affecting minority groups, such as unequal access to guideline-concordant mental healthcare (Young, Klap, Sherbourne, & Wells, 2001), limited availability of language-matched services (Lanouette et al., 2009), lack of adequate health insurance (González, et al., 2009; Lanouette et al., 2009), lower detection of depressive illness (Borowsky, et al., 2000), and less proactive and participatory communication strategies by providers (Cooper-Patrick, et al., 1999; Sleath, Rubin, & Huston, 2003; Schraufnagel, Wagner, Miranda, & Roy-Byrne, 2006).

Non-adherence among underserved racial/ethnic groups persists, however, even when several of these factors are accounted for. Among US Latinos, for example, lower initiation of antidepressant prescription is found relative to Whites in insured samples and even after adjusting for demographic characteristics and insurance status (Harman et al., 2004; Miranda & Cooper, 2004; Olfson et al., 2006). Lower antidepressant therapy retention persists in trials where treatment is language-matched, free of cost, and/or subsidized for the uninsured (Arnow, et al., 2007; Sánchez-Lacay et al., 2001; Warden et al., 2007; Warden, et al., 2009).

Cultural factors salient among Latinos have been proposed to help explain the lower adjusted odds of antidepressant therapy adherence relative to Whites. These include: lower preference for antidepressants (Givens, Houston, Van Voorhees, Ford, & Cooper, 2007; Miranda & Cooper, 2004), more concern that these medications are harmful, addictive, and ineffective for treating depression (Cabassa, Lester, & Zayas, 2007; Givens et al., 2007; Interian, Martínez, Iglesias Ríos, Krejci, & Guarnaccia, 2010), greater stigmatization of psycho-pharmacotherapy (Interian, Ang, Gara, Link, Rodríguez, & Vega, 2010; Lanouette et al., 2009; Martínez-Pincay & Guarnaccia, 2007), illness constructions inconsistent with antidepressant therapy (Cabassa et al., 2007; Lewis-Fernández, Das, Alfonso, Weissman, & Olfson, 2005; Schraufnagel et al., 2006), greater reliance on faith-based services to cope with depression (Cabassa et al., 2007; Givens et al., 2007), lower likelihood of communicating complaints to clinicians about antidepressants (Sleath, Rubin, & Wurst, 2003), and more unmet expectations about how clinicians should engage them in treatment (Cortés, Mulvaney-Day, Fortuna, Reinfeld, & Alegría, 2009; Interian, Martínez, et al., 2010; Martínez-Pincay & Guarnaccia, 2007; Schraufnagel et al., 2006). In line with the importance of cultural factors, lower acculturation among Latinos is associated with lower past-year use of antidepressants and with poorer antidepressant therapy adherence, even after adjusting for education, insurance status, and other sociodemographic and clinical covariates (González et al., 2009; Hodgkin, Volpe-Vartanian, & Alegría, 2007).

Interventions designed to enhance adherence with mental health treatment among Latino patients are hypothesized to be most efficacious if they address these cultural factors; however, research in this area remains very sparse (Lanouette et al., 2009). It is unclear if cultural adaptation is needed, since the relative efficacy in Latinos of existing adherence-enhancing interventions is unknown, due to insufficient inclusion of minorities to assess moderator effects or conduct subgroup analyses (Schraufnagel et al., 2006). In the past, interventions for improving access to guideline-concordant care that paid some attention to cultural factors increased Latino engagement in depression care, but did not succeed in closing the gap with non-Latino Whites (Miranda, et al., 2003). These engagement disparities remained after controlling for intervention status, stated preference for depression treatment, and other covariates (Dwight-Johnson, Unutzer, Sherbourne, Tang, & Wells, 2001).

To our knowledge, only one adherence intervention has been developed specifically for Latino patients in antidepressant therapy. Interian and colleagues developed Motivational Enhancement Therapy for Antidepressants (META), a 3-session culturally adapted adherence intervention based on Motivational Interviewing that is administered adjunctively to standard antidepressant therapy (Interian, Martínez, et al, 2010). In a pilot study, META was significantly more efficacious than usual care in enhancing antidepressant adherence over five months of antidepressant therapy (Interian, Lewis-Fernández, Gara, & Escobar, under review). META, however, relies on adjunctive clinicians, which may limit its implementation in low-resource clinical settings where most Latinos receive care; its adjunctive design may also cause it to require regular booster sessions to maintain its effect over time (Zygmunt, Olfson, Boyer, & Mechanic, 2002). In addition, META's impact on other aspects of non-adherence, such as treatment retention, has not been assessed.

To facilitate sustainable implementation in low-resource settings, we developed a novel adherence intervention that does not rely on ancillary personnel and is culturally adapted for Latino patients in pharmacotherapy for Major Depressive Disorder. The development and main features of Motivational Pharmacotherapy are described in our companion article in this issue (Balán, Moyers, & Lewis-Fernández, YEAR); the full manual is available at: http://www.nyspi.org/culturalcompetence/what/reports.html. Motivational Pharmacotherapy works by reorienting the way psychiatrists conduct pharmacotherapy without adding extra sessions, integrating antidepressant therapy and Motivational Interviewing into a collaborative, directive approach that focuses on increasing patients’ intrinsic motivation to change and reducing their ambivalence about treatment (Miller & Rollnick, 2002; 2009). Motivational Pharmacotherapy targets all aspects of non-adherence once a patient has accessed antidepressant therapy, including retention and medication taking. While developed for depressed Latino outpatients with Major Depressive Disorder, Motivational Pharmacotherapy can be modified for other cultural groups and psychiatric disorders. Cultural validity is enhanced because Motivational Pharmacotherapy follows Motivational Interviewing in eliciting the reasons for behavior change and the commitment to carry it out from the patients themselves, an approach proven efficacious with underserved racial/ethnic groups (Field, Caetano, Harris, Frankowski, & Roudsari, 2009; Hettema, Steele, & Miller, 2005). Moreover, approaches based on Motivational Interviewing are effective in very brief encounters (e.g., 15 minutes), consistent with standard pharmacotherapy practice, and when implemented by diverse types of providers, including physicians (Rubak, Sandboek, Lauritzen, & Christensen, 2005).

This article reports the results of a pilot study on the first stage of the development of Motivational Pharmacotherapy; this first stage usually focuses on manualization, feasibility, and preliminary efficacy (Carroll & Onken, 2005). Our trial focused on the impact of Motivational Pharmacotherapy on antidepressant therapy retention, response, and visit duration among first-generation Latinos with Major Depressive Disorder. These three outcomes are basic elements of pharmacotherapy effectiveness because interventions that increase retention at the expense of treatment response or that take too long to administer are unlikely to be implemented. Above all, we wanted to see whether Motivational Interviewing could feasibly be balanced with the structured and directive nature of medication management in a way that resulted in improved retention. To enhance the cultural fit of our approach, the content of Motivational Pharmacotherapy was tailored for this study to the cultural views and concerns about antidepressant therapy among less-acculturated Latinos.

METHODS

Participants

Fifty adult Latino outpatients participated in the study from January, 2003 to March, 2006; ethnicity was self-reported. Patients were recruited by advertisement, clinical referral, and word-of-mouth. Participants fulfilled criteria for Major Depressive Disorder on the clinician-administered Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1998), and had at least moderate severity at baseline (score ≥ 18) on the 17-item Hamilton Depression Scale (Hamilton, 1960). Patients could not receive any depression treatment other than study medication during the 12-week trial, including psychotherapy. At baseline, all patients expressed a willingness to take medication for their Major Depressive Disorder. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the New York State Psychiatric Institute.

Treatment

Patients received twelve weeks of open-label antidepressant therapy delivered by a psychiatrist. Treatment was offered in English or Spanish, as the patient preferred. Medication selection was standardized to a sequence of sertraline, venlafaxine XR, and bupropion SR, with switches depending on response and tolerability. Patients who exhibited prior intolerance or non-response to an adequate trial of one of these agents were skipped to the next medication in the sequence (only one patient was started on venlafaxine XR instead of sertraline because of this reason). Medication visits were scheduled weekly during the first month, then every other week until the end of treatment. Same-week rescheduling in the case of missed appointments was allowed.

All sessions followed the Motivational Pharmacotherapy manual in a manner consistent with the empathic, collaborative, and autonomy-supportive approach of Motivational Interviewing. This general style, present in all visits, was supplemented in weeks 0, 1, 4 and 8 with a more structured series of processes and tasks, resulting in four culturally adapted, manualized “enhanced” sessions. Specifically, weeks 0-1 focused on increasing perceived importance for initiating antidepressant therapy and promoting self-confidence in patients’ ability to complete treatment. Psychiatrists explored antidepressant therapy-related concerns and addressed them in line with patients’ cultural illness constructions. For example, lists derived from our previous qualitative work with low-income Latinos provided illustrations of potential concerns about antidepressant therapy (Lewis-Fernández, 2003), and medication choices were negotiated taking into account patients’ treatment expectations about cultural syndromes (e.g., nervios [nerves]), such as low initial doses, very slow dose increases, and brief drug holidays as requested to enable nerves “to adjust or recover on their own.” Weeks 4 and 8 focused on issues commonly threatening retention, including side effects, fear of addiction, and doubts about need for ongoing medication. Affirmation of patients’ progress and their desire to remain free of depression were used to reinforce treatment retention. During all sessions, the psychiatrist affirmed patient willingness to continue with the treatment and asked about adherence to the medication. Obstacles to adherence were discussed with the goal of helping the patient identify ways of overcoming them

Motivational Interviewing Training and Treatment Fidelity

Three Latino psychiatrists underwent two-day clinical training in Motivational Interviewing, followed by biweekly, then monthly, phone-based supervision with a senior consultant (TBM) aimed at improving Motivational Interviewing skills. The Motivational Interviewing treatment sessions were audiotaped and reviewed for fidelity to Motivational Interviewing, using an instrument developed for this study. The instrument incorporated aspects of the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity scale (version 2.0; Moyers, Martin, Manuel, Miller, & Ernst, 2003; Moyers, Martin, Manuel, Hendrickson, & Miller, 2005) as well as tasks that were specific to Motivational Pharmacotherapy. Overall, 47% of “enhanced” sessions were reviewed for fidelity (n=86), including 69% of sessions for the first 15 patients (n=38). To accommodate elements of pharmacotherapy that conflict with a pure Motivational Interviewing approach (e.g., sequential closed questions to assess key medication effects), acceptable fidelity was set at 4 on a 7-point Likert scale that captured the degree to which the session was conducted in a Motivational Interviewing-consistent manner. Mean scores for overall Motivational Interviewing fidelity (4.45; SD=1.01) and compliance to specific intervention tasks (4.16; SD=1.30) were acceptable. During the study, session ratings were used to identify areas requiring further Motivational Interviewing skills training during supervision.

Measures

Primary outcome was treatment retention, in keeping with our goal of increasing patient's adherence behavior. Retention was defined in two ways, continuously as days in treatment and dichotomously as discontinuation, defined as: i) premature termination, ii) missing two consecutive medication appointments, or iii) remaining off medication for ≥7 days (Sánchez-Lacay et al., 2001). The dichotomous measure allowed us to compare Motivational Pharmacotherapy with previous efficacy studies among Latinos that used similar definitions (e.g., Sánchez-Lacay et al., 2001; Wagner, Maguen, & Rabkin, 1998). The continuous measure included patients who discontinued the research trial but returned for open treatment over the 12-week study period, making the measure less sensitive to cross-study methodological variation and enabling comparison to previous antidepressant trials at our clinic. Every patient was therefore offered a minimum of 84 days of treatment (this includes post-intervention antidepressant therapy for participants in 8-week trials and for those who dropped out to receive medications that had been excluded during study treatment). We summed the days between kept visits to calculate the continuous number of days patients were retained in pharmacotherapy.

Other outcome measures were: depressive symptoms, using the clinician-rated Hamilton Depression Scale; functional impairment, using the self-report Sheehan Disability Scale total score and work, family, and leisure subscores (Sheehan, Harnett-Sheehan, & Raj, 1996); and perceived quality of life using the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (Endicott, Nee, Harrison, & Blumenthal, 1993). The Bidimensional Acculturation Scale yielded separate scores (range 1-5) for “Latino” and “non-Latino” cultural orientations, enabling the assessment of biculturality, defined by a score >2.5 on each subscale (Marín & Gamba, 1996).

Response was defined as reduction in 17-item Hamilton Depression Scale total score of ≥50%, and remission as response plus a final 17-item Hamilton Depression Scale score <8. A random 20% subsample of “enhanced” sessions (n=36) was timed using audiotapes, stratified across visit week (0 vs. 1, 4, 8), to assess transferability of Motivational Pharmacotherapy to outpatient community practice.

Statistical Analyses

Treatment response outcomes were analyzed for the intention-to-treat sample, including all participants dispensed medication. Change in continuous outcome measures from week 0 to endpoint was assessed using paired t-tests. Comparisons between retained and non-retained patients were made using Chi-square tests for categorical variables and t-tests for continuous variables. All statistical tests were two-tailed with level of significance α≤.05.

RESULTS

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the participants. The sample had a fairly even gender and marital status distribution, a mean age of 39.8, and 11 years of education on average. Nearly all patients (98%) were first-generation Latin American immigrants who spoke only Spanish (92%). Seventy percent of the sample was born in the Dominican Republic, Mexico, or Ecuador. Typical for first-generation Latinos in New York City, the yearly household income of 83% was <$20,000, despite a majority of participants (68%) being employed. The mean Bidimensional Acculturation Scale levels were 3.3 (SD=0.3) for “Latino” and 1.8 (SD=0.6) for “non-Latino” orientation (p<.001). Only 11% of respondents had a bicultural orientation. Motivational Pharmacotherapy was conducted in Spanish with all but one participant.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the sample (N=50)

| Patient characteristic | n (%) | mean (sd) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 24 (48%) | |

| Female | 26 (52%) | |

| Age | 39.8 (12.2) | |

| Marital status | ||

| Single (never married) | 18 (36%) | |

| Married/living with partner | 17 (34%) | |

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 15 (30%) | |

| Years of education | 11.0 (3.7) | |

| Employment Status | ||

| Employed | 34 (68%) | |

| Out of workforce | 4 (8%) | |

| Unemployed | 12 (24%) | |

| Income1 | ||

| $9,999 or less | 25 (52%) | |

| $10,000-$19,999 | 15 (31%) | |

| $20,000 or more | 8 (17%) | |

| Country of birth | ||

| Dominican Republic | 16 (32%) | |

| Mexico | 9 (18%) | |

| Ecuador | 10 (20%) | |

| Other Latin American country | 14 (28%) | |

| Continental USA | 1 (2%) | |

| Language fluency | ||

| Spanish monolingual | 46 (92%) | |

| Bilingual (English/Spanish) | 4 (8%) |

Two patients did not provide income information

Proportion of non-retention from Motivational Pharmacotherapy was 20% (n=10/50) at twelve weeks. Patients stayed in Motivational Pharmacotherapy M=74.2 days (SD=23) out of a possible 84 (88.3%; 95% CI: 80.95-95.9%). (In fact, participation in the enhanced sessions over the first 8 weeks of treatment was 90.5% , or 181/200 visits.) Non-retention was not significantly associated with age (p=.23), gender (p=.49), or level of education (p=.64). Five of the 10 non-retained patients discontinued treatment because of logistical barriers involving work, housing, or family issues; the other five discontinued treatment due to ongoing ambivalence about antidepressant therapy. Eighty-eight percent of patients ended their participation in the trial on the first medication they were prescribed, which was sertraline in all but one case. The proportion of patients switching antidepressants did not differ significantly between non-retained (n=2/10; 20%) and retained patients (n=4/40; 10%) (p=.51).

Patients’ depression symptoms, psychosocial functioning, and quality of life showed significant improvement from baseline to endpoint (Table 2). Responder and remitter rates were 82% and 68%, respectively. In terms of visit duration, mean length of treatment sessions was 36.7 minutes (SD=13.3) for visit 1 (week 0) and 24.3 minutes (SD=11.2) for visits on weeks 1, 4, and 8.

Table 2.

Outcome assessments at baseline and after 12 weeks of Motivational Pharmacotherapy (N=50)

| Outcome | n (%) | mean (sd) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Assessment | Baseline mean (sd) | Week 12 mean (sd) | Change mean (sd) | t-value | p-value |

| HAMD17 | 23.6 (3.5) | 7.7 (7.0) | −15.9 (7.9) | 14.2 | <0.001 |

| SDS overall | 18.2 (7.2) | 13.9 (7.7) | −4.3 (7.6) | 3.8 | <0.001 |

| SDS – work | 5.4 (3.1) | 4.1 (3.0) | −1.3 (2.7) | 3.2 | 0.002 |

| SDS – family | 6.7 (2.9) | 5.1 (2.9) | −1.6 (3.1) | 3.7 | <0.001 |

| SDS – leisure | 6.4 (3.0) | 5.0 (2.9) | −1.4 (3.7) | 2.4 | 0.02 |

| Q-LES-Q | 41.4 (13.0) | 55.0 (17.7) | 13.6 (16.6) | 5.4 | <0.001 |

Note: Paired t-test with 45 degrees of freedom, with two exceptions: HAMD17 (49 df) and SDS-Work (43 df).

HAMD17 = Hamilton Depression Scale, 17-item version; SDS = Sheehan Disability Scale; Q-LES-Q = Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire

DISCUSSION

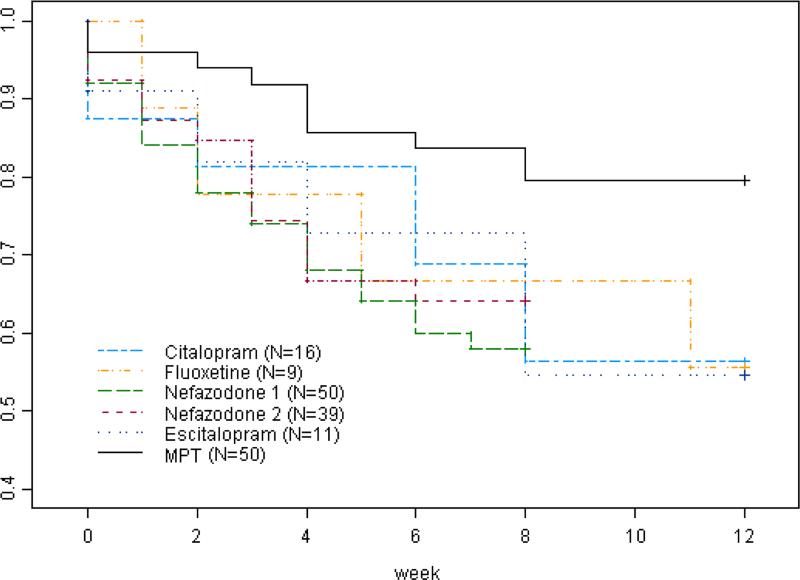

Our pilot results show that it is feasible to integrate pharmacotherapy for Major Depressive Disorder and Motivational Interviewing into a novel Motivational Pharmacotherapy approach for use by outpatient psychiatrists. Motivational Pharmacotherapy was associated with a low proportion of discontinuation of 20% at 12 weeks in a low-income, low-acculturated Latino sample. This compares favorably with antidepressant therapy non-retention proportions among depressed Latinos of 32-53% in prior 8-12-week open and controlled outpatient trials (Alonso, Val, & Rapaport, 1997; Wagner et al., 1998; Warden et al., 2007) and of 36-54% in 4-14 weeks of naturalistic follow-up in clinical settings (Bull, Hu, Hunkeler, Lee, Ming, Markson, & Fireman, 2002; Olfson et al., 2006). Previous studies of antidepressant therapy at our research clinic with a similar Latino sample using the same bilingual, bicultural psychiatrists (prior to their Motivational Interviewing training) also showed substantially higher proportions of discontinuation (Sánchez-Lacay et al., 2001), ranging from 36-42% at 8 weeks (N=89) to 44-46% at 12 weeks (N=36; see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Treatment retention among depressed Hispanic outpatients in Motivational Pharmacotherapy vs. historical controls on standard antidepressant therapy

Our findings should be considered in light of various limitations common to pilot projects. Because of the open trial methodology, we lacked a comparison group or randomization to assess efficacy. We recruited study participants largely through advertising and referral, therefore the generalizability of this sample to other Latino samples is unknown. All of our psychiatrists were bilingual, bicultural Latinos, raising the question whether intervention feasibility would be equivalent with clinicians from other backgrounds. Without a follow-up assessment, we could not evaluate the durability of the Motivational Pharmacotherapy effect on treatment response. Limited funds prevented us from formally assessing medication adherence via electronic tracking devices in order to evaluate other aspects of treatment adherence besides retention. Our continuous measure of antidepressant retention did not assess medication adherence, only days in pharmacotherapy. Finally, although a strength of the study is the focus on low-acculturation Latinos, a population with very high non-retention rates, greater sample diversity is needed to assess Motivational Pharmacotherapy efficacy more broadly.

Comparison using the continuous measure of retention supports the impact of Motivational Pharmacotherapy. Patients in Motivational Pharmacotherapy stayed in treatment M=74.2 days (SD=30) (88% of 84 total days), compared to M=58.0 days (SD=30) (69% of total) in previous studies at our clinic (N=125). We cannot be certain, however, to what extent this higher retention was associated with factors other than the Motivational Interviewing component of Motivational Pharmacotherapy. Methodological differences across studies may also be involved and preclude formal statistical comparison, such as differences in trial duration, antidepressant, rules about medication switching, visit frequency, and psychiatric comorbidity. Nevertheless, use of the continuous retention measure reduces the impact of some of these differences, particularly those due to trial duration and medication switching, and all the studies except one (fluoxetine, n=9) followed the same open-trial design. Moreover, even if the Motivational Pharmacotherapy trial design had not allowed antidepressant switching, and all four patients retained on Motivational Pharmacotherapy who switched medications had discontinued treatment, the non-retention rate from Motivational Pharmacotherapy would have been 28%, a substantially lower proportion than the 44-46% who discontinued antidepressant therapy in the non-Motivational Pharmacotherapy 12-week trials at our clinic.

Our data suggests that Motivational Pharmacotherapy helped patients overcome some of the barriers that may sustain Latino non-adherence above and beyond issues of cost, language, and other access factors. Particularly striking at our clinic were the elevated rates of non-retention prior to the introduction of Motivational Pharmacotherapy despite the fact that antidepressant therapy was provided as open treatment, with FDA-approved medications, free of cost, in Spanish, by the same Latino psychiatrists who later conducted the Motivational Pharmacotherapy study, to patients with at least moderate levels of Major Depressive Disorder, and in a setting with an extensive network of public transportation. Persistent non-retention despite attention to these clinical and logistical factors has characterized previous research with depressed Latinos. In the STAR*D trial, for example, where bilingual clinicians were available, medications were free, and all patients were insured or received care at no cost, non-retention was still significantly higher among Latinos than non-Latinos during the first 12 weeks of citalopram treatment (Warden et al., 2007, online addendum). Moreover, being Latino was associated with 3.3 higher odds of non-retention in the second stage of treatment, after 12 additional weeks of treatment augmentation with other medications or psychotherapy, even after adjusting for clinical and demographic characteristics (Warden et al., 2009). These findings suggest that some feature(s) of Motivational Pharmacotherapy helped Latino patients overcome their concerns and ambivalence about antidepressant therapy in order to remain in treatment.

This study was not designed to identify which aspects of Motivational Pharmacotherapy facilitated retention. Possibilities include specific components of Motivational Interviewing (e.g., collaborative style [Robbins, et al., 2006] or promotion of change talk and commitment language [Moyers, Martin, Houck, Christopher, & Tonigan, 2009]) and cultural congruence of Motivational Pharmacotherapy with our Latino sample. Cultural aspects that may have promoted retention are: a) the way solutions to problems are elicited from the patients themselves rather than from providers, thereby minimizing culturally incongruous recommendations (Hettema et al., 2005; Interian, Martínez, et al., 2010); b) the ease with which culture-specific content is included in Motivational Interviewing (e.g., lists of concerns about treatment derived from previous work with this population); and c) the inherent cultural match between Motivational Interviewing and the values and treatment expectations of many low-acculturation Latinos (e.g., enhancing confianza [trust] through clinician-patient collaboration; minimizing the direct expression of interpersonal conflict, especially in interactions with respected figures such as physicians [Interian, Martínez, et al., 2010]).

Although our trial focused on treatment retention, other outcome measures further support the usefulness of Motivational Pharmacotherapy, which resulted in significant improvement in symptoms, functioning, and quality of life, and in high rates of response and remission for our participants. This is consistent with previous research showing that for antidepressant trials Latino completers have had high response rates (Sánchez-Lacay et al., 2001; Escobar & Tuason, 1980), highlighting the importance of retention as a key mediator of treatment outcome in this population. If the efficacy of our Motivational Interviewing-based approach for improving retention of depressed Latinos in pharmacotherapy is confirmed by future research, it could substantially impact treatment outcome.

In terms of visit duration, Motivational Pharmacotherapy appears highly transferable to community settings. At 37 minutes for the first visit and especially at 24 minutes for the subsequent enhanced visits at weeks 1, 4, and 8, visit duration was acceptable for many outpatient clinics. This compares favorably to the average duration of community-based psychiatrist visits in the United States, which was 32-38 minutes per visit in 1989-2006 (Mechanic, McAlpine, & Rosenthal, 2001; Olfson, Cherry, & Lewis-Fernández, 2009; Olfson, Marcus, & Pincus, 1999). Motivational Pharmacotherapy also has the advantage of being conducted within the psychiatrist visit, rather than by adding ancillary Motivational Interviewing sessions with another clinician, thus decreasing service burden. In addition, Motivational Pharmacotherapy may have little need for booster sessions during long-term pharmacotherapy, since the adherence-enhancing component is an integral feature of the delivery of antidepressant therapy itself, leading to potential cost savings.

Questions remain, however, about the generalizability of our pilot findings and the implementability of Motivational Pharmacotherapy. In terms of generalizability, how characteristic is our sample compared to all US Latinos with Major Depressive Disorder? For example, does the unusually even gender distribution of our sample (possibly related to their status as migrants) affect the impact of the intervention? As a rough test of generalizability, we applied the trial's inclusion-exclusion criteria to a nationally representative, community-based sample of US Latinos with Major Depressive Disorder assessed in the National Epidemiological Survey for Alcohol and Related Conditions (Blanco et al., 2008). Fifty-seven percent of all US Latinos with Major Depression and 69.6% of those who sought mental health treatment in the past year would be excluded from our study, largely because of suicidal ideation, substance use disorders, and chronic medical conditions. While our study is more generalizable than most depression trials, which exclude over 75% of community members (Blanco et al., 2008), additional research is needed to confirm the broad applicability of Motivational Pharmacotherapy.

In terms of implementability, mental health interventions are increasingly being evaluated regarding their potential implementation in public health settings from early in their development (Lagomasino, Zatzick, & Chambers, 2010). How implementable is Motivational Pharmacotherapy? Would low-resource clinics be able to support the financial and logistical costs of training and supervising psychiatrists in the new approach? How effective is the intervention when not conducted by ethnically-matched psychiatrists? To what extent could Motivational Pharmacotherapy be adapted for use in medical settings, such as primary care, where the visits are shorter than in community psychiatry? Other Motivational Interviewing approaches are effective in primary care (Rubak, Sandboek, Lauritzen, & Christensen, 2005), arguing for a possible role for Motivational Pharmacotherapy. We intend to focus on some of these questions in a future implementation trial.

First, however, we are currently engaged in the second stage of Motivational Pharmacotherapy development, by conducting a randomized study of Motivational Pharmacotherapy compared to standard antidepressant therapy, assessing treatment retention separately from medication adherence, and identifying mediators and moderators of intervention effect. If Motivational Pharmacotherapy is found to be more efficacious than standard antidepressant therapy, it would be appropriate to assess its implementability as an adherence-enhancement Evidence-Based Practice in diverse populations at risk for pharmacotherapy non-adherence.

Acknowledgments

The project was directly supported by research grant R21 MH 066388 from the National Institute of Mental Health. Study medication (sertraline) and additional financial support were provided by Pfizer, Inc. The study was supported in part by institutional funds from New York State Psychiatric Institute (Lewis-Fernández, Patel, Sánchez-Lacay, Blanco, and Schneier), as well as by R01 MH 077226 (Lewis-Fernández) and DA023200 and MH076051 (Blanco).

The authors wish to thank Peter Guarnaccia, Michael R. Liebowitz, Paula Yáñes, Ashley Henderson, Donna Vermes, Ian Tope, Melissa Rosario, Yélida Saldívar, Page Van Meter, José Hernández, Jennifer Humensky, Leopoldo Cabassa, Blair Simpson, Shuai Wang, and John Markowitz for their help with this research.

Footnotes

Disclosure of Conflicts of Interest:

In addition to the funding acknowledged in the above section, the following authors currently receive financial support from the listed industry sources to conduct research studies: Lewis-Fernández (Lilly) and Schneier (Forest). In addition, Dr. Schneier is on the advisory board of Jazz Pharmaceuticals. The remaining authors have no interests to disclose.

Trial Registration: clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT00057642

REFERENCES

- Alonso M, Val E, Rapaport MH. An open-label study of SSRI treatment in depressed Hispanic and non-Hispanic women. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1997;58:31. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v58n0106c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnow BA, Blasey C, Manber R, Constantino MJ, Markowitz JC, Klein DN, Rush AJ. Dropouts versus completers among chronically depressed outpatients. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2007;97:197–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2006.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balán I, Moyers T, Lewis-Fernández R. Motivational Pharmacotherapy: Combining motivational interviewing and antidepressant therapy to improve treatment adherence. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2013.76.3.203. YEAR Manuscript submitted for publication. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco C, Olfson M, Goodwin RD, Ogburn E, Liebowitz MR, Nunes EV, Hasin DS. Generalizability of clinical trial results for major depression to community samples. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2008;69:1276–1280. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borowsky SJ, Rubenstein LV, Meredith LS, Camp P, Jackson-Triche M, Wells KB. Who is at risk of nondetection of mental health problems in primary care? Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2000;15:381–388. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.12088.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull SA, Hu XH, Hunkeler EM, Lee JY, Ming EE, Markson LE, Fireman B. Discontinuation of use and switching of antidepressants: Influence of patient-physician communication. JAMA. 2002;288:1403–1409. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.11.1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabassa LJ, Lester R, Zayas LH. “It's like being in a labyrinth”: Hispanic immigrants’ perceptions of depression and attitudes toward treatments. Journal of Immigrant Health. 2007;9:1–16. doi: 10.1007/s10903-006-9010-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Onken LS. Behavioral therapies for drug abuse. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162:1452–1460. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.8.1452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper-Patrick L, Gallo JJ, Gonzales JJ, Vu HT, Powe NR, Nelson C, Ford DE. Race, gender, and partnership in the patient-physician relationship. JAMA. 1999;282:583–589. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.6.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortés DE, Mulvaney-Day N, Fortuna L, Reinfeld S, Alegría M. Patient-provider communication: Understanding the role of patient activation for Latinos in mental health treatment. Health Education and Behavior. 2009;36:138–154. doi: 10.1177/1090198108314618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dwight-Johnson M, Unutzer J, Sherbourne C, Tang L, Wells KB. Can quality improvement programs for depression in primary care address patient preferences for treatment? Medical Care. 2001;39:934–944. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200109000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endicott J, Nee J, Harrison W, Blumenthal R. Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire: A new measure. Psychopharm Bulletin. 1993;29:321–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobar JI, Tuason VB. Antidepressant agents: A cross-cultural study. Psychopharm Bulletin. 1980;16:49–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field CA, Caetano R, Harris TR, Frankowski R, Roudsari B. Ethnic differences in drinking outcomes following a brief alcohol intervention in the trauma care setting. Addiction. 2009;105:62–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02737.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Patient Edition (SCID I/P, Version 2.0 9/98 revision) Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Givens JL, Houston TK, Van Voorhees BW, Ford DE, Cooper LA. Ethnicity and preferences for depression treatment. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2007;29:182–191. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González HM, Tarraf W, West BT, Croghan TW, Bowen ME, Cao Z, Alegría A. Antidepressant use in a nationally representative sample of community-dwelling US Latinos with and without depressive and anxiety disorders. Depression and Anxiety. 2009;26:674–681. doi: 10.1002/da.20561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.23.1.56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harman JS, Edlund MJ, Fortney JC. Disparities in the adequacy of depression treatment in the United States. Psychiatric Services. 2004;55:1379–1385. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.12.1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettema J, Steele J, Miller WR. Motivational Interviewing. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2005;1:91–111. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.1.102803.143833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkin D, Volpe-Vartanian J, Alegría M. Discontinuation of antidepressant medication among Latinos in the USA. Journal of Behavioral Health Services Research. 2007;34:329–342. doi: 10.1007/s11414-007-9070-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Interian A, Martínez I, Iglesias Ríos L, Krejci J, Guarnaccia PJ. Adaptation of a motivational interviewing intervention to improve antidepressant adherence among Latinos. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2010;16:215–225. doi: 10.1037/a0016072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Interian A, Ang A, Gara MA, Link BG, Rodríguez MA, Vega WA. Stigma and depression treatment utilization among Latinos: Utility of four stigma measures. Psychiatric Services. 2010;61:373–379. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.61.4.373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Interian A, Lewis-Fernández R, Gara MA, Escobar JI. A randomized, controlled trial of an intervention to improve antidepressant adherence among Latinos. doi: 10.1002/da.22052. under review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagomasino IT, Zatzick DF, Chambers D. Efficiency in mental health practice and research. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2010;32:477–483. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanouette NM, Folsom DP, Sciolla A, Jeste DV. Psychotropic medication non-adherence among United States Latinos: A comprehensive literature review. Psychiatric Services. 2009;60:157–174. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.60.2.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Fernández R. Role of cultural expectations of treatment in adherence research.. Presentation at the NIMH Training Conference Beyond the Clinic Walls: Expanding Mental Health, Drug and Alcohol Services Research Outside the Specialty Care System; Rockville, MD. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Fernández R, Das AK, Alfonso C, Weissman MM, Olfson M. Depression in US Hispanics: Diagnostic and management considerations in family practice. Journal of the American Board of Family Practice. 2005;18:282–296. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.18.4.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marín G, Gamba RJ. A new measurement of acculturation for Hispanics: The Bidimensional Acculturation Scale for Hispanics (BAS). Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1996;18:297–316. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez-Pincay IE, Guarnaccia PJ. “It's like going through an earthquake”: Anthropological perspectives on depression among Latino immigrants. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2007;9:17–28. doi: 10.1007/s10903-006-9011-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechanic D, McAlpine D, Rosenthal M. Are patients' office visits with physicians getting shorter? New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;344:198–204. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200101183440307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People for Change. 2nd Edition Guilford; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Ten things that motivational interviewing is not. Behavioral and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2009;37(2):129–140. doi: 10.1017/S1352465809005128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda J, Cooper LA. Disparities in care for depression among primary care patients. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2004;19:120–126. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30272.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda J, Duan N, Sherbourne C, Shoenbaum M, Lagomasino I, Jackson-Triche M, Wells KB. Improving care for minorities: Can quality improvement interventions improve care and outcomes for depressed minorities?: Results of a randomized, controlled trial. Health Services Research. 2003;38:613–630. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.00136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB, Martin T, Houck JM, Christopher PJ, Tonigan JS. From in-session behaviors to drinking outcomes: A causal chain for motivational interviewing. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:1113–1124. doi: 10.1037/a0017189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB, Martin T, Manuel JK, Miller WR, Ernst D. The Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity (MITI) Coding Manual. University of New Mexico Center on Alcoholism, Substance Abuse and Addictions (CASAA); Albuquerque, NM: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB, Martin T, Manuel JK, Hendrickson SML, Miller WE. Assessing competence in the use of motivational interviewing. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2005;28:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M, Marcus SC, Pincus HA. Trends in office-based psychiatric practice. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:451–457. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.3.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M, Marcus SC, Tedeschi M, Wan GJ. Continuity of antidepressant treatment for adults with depression in the United States. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:101–108. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M, Cherry DK, Lewis-Fernández R. Racial differences in visit duration of outpatient psychiatric visits. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2009;66:214–221. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2008.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins M, Liddle H, Turner CW, Dakof GA, Alexander JF, Kogan SM. Adolescent and parent therapeutic alliances as predictors of dropout in multidimensional family therapy. Journal of Family Psychology. 2006;20:108–116. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.20.1.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubak S, Sandboek A, Lauritzen T, Christensen B. Motivational interviewing: A systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of General Practice. 2005;55:305–312. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Lacay JA, Lewis-Fernández R, Goetz D, Blanco C, Salmán E, Davies S, Liebowitz M. Open trial of nefazodone among Hispanics with major depression: Efficacy, tolerability, and adherence issues. Depression and Anxiety. 2001;13:118–124. doi: 10.1002/da.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schraufnagel TJ, Wagner AW, Miranda J, Roy-Byrne P. Treating minority patients with depression and anxiety: What does the evidence tell us? General Hospital Psychiatry. 2006;28:27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Harnett-Sheehan K, Raj AB. The measurement of disability. International Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1996;11:89–95. doi: 10.1097/00004850-199606003-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleath B, Rubin RH, Huston SA. Hispanic ethnicity, physician-patient communication, and antidepressant adherence. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2003;44:198–204. doi: 10.1016/S0010-440X(03)00007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleath B, Rubin RH, Wurst K. The influence of Hispanic ethnicity on patients’ expression of complaints about and problems with adherence to antidepressant therapy. Clinical Therapeutics. 2003;25:1739–1749. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(03)80166-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner GJ, Maguen S, Rabkin JG. Ethnic differences in response to fluoxetine in a controlled trial with depressed HIV-positive patients. Psychiatric Services. 1998;49:239–240. doi: 10.1176/ps.49.2.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warden D, Trivedi MH, Wisniewksi SR, Davis L, Nierenberg AA, Gaynes BN, Rush AJ. Predictors of attrition during initial (citalopram) treatment for depression: A STAR*D report. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164:1189–1197. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06071225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warden D, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, Lesser IM, Kornstein SG, Balasubramani GK, Trivedi MH. What predicts attrition in second step medication treatments for depression?: A STAR*D report. International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;12:459–473. doi: 10.1017/S1461145708009073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young AS, Klap R, Sherbourne CD, Wells KB. The quality of care for depressive and anxiety disorders in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58:55–61. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zygmunt A, Olfson M, Boyer CA, Mechanic D. Interventions to improve medication adherence in schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:1653–1664. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.10.1653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]