Abstract

Background

In addition to patient self-efficacy, spouse confidence in patient efficacy may also independently predict patient health outcomes. However, the potential influence of spouse confidence has received little research attention.

Purpose

The current study examined the influence of patient and spouse efficacy beliefs for arthritis management on patient health.

Methods

Patient health (i.e., arthritis severity, perceived health, depressive symptoms, lower extremity function), patient self-efficacy, and spouse confidence in patients’ efficacy were assessed in a sample of knee osteoarthritis patients (N = 152) and their spouses at three time points across an 18-month period. Data were analyzed using structural equation models.

Results

Consistent with predictions, spouse confidence in patient efficacy for arthritis management predicted improvements in patient depressive symptoms, perceived health, and lower extremity function over 6 months and in arthritis severity over 1 year.

Conclusions

Our findings add to a growing literature that highlights the important role of spouse perceptions in patients’ long-term health.

Keywords: Arthritis, Chronic illness, Couples, Longitudinal, Self-efficacy

As the US’ population ages, the prevalence of chronic illnesses will become more widespread and place added pressure on an already strained health care system. Therefore, it is important to understand how the effects of chronic illness on patients can be mitigated, particularly the social factors that may promote better adjustment to illness and maintenance of physical and mental health over time. In the current paper, we focus on the role of efficacy beliefs in managing pain and other symptoms in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Specifically, we examine whether patients’ self-efficacy and spouses’ confidence in the efficacy of patients to manage arthritis predict changes in the patients’ health over time in a three-wave longitudinal study.

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a degenerative condition in which joint cartilage breaks down over time, resulting in joint pain, chronic inflammation, and joint stiffness [1]. OA is especially problematic when it affects the knees, causing significant limitations in mobility and daily activities, and the lifetime risk of developing symptomatic OA in one or both knees is 44.7 % [2]. The effective management of joint pain is one of the primary goals of treatment, as the pain can be debilitating for arthritis patients and result in limitations in the performance of daily activities [1, 3]. Furthermore, the pain can place patients at risk for depressive symptoms [3]. Thus, knee OA tends to be a condition that gets worse over time, with many patients experiencing increasing disability and limitations in their day-to-day activities.

One factor that has been shown to be particularly important for being able to manage the symptoms of arthritis is patient self-efficacy [3]. Self-efficacy refers to a person’s confidence in their own ability to perform the actions necessary to obtain a desired outcome [4, 5]. In the context of arthritis management, self-efficacy has been conceptualized as patients’ beliefs about their ability to enact the behaviors necessary to control their pain and prevent the worsening of their arthritis symptoms over time [3]. Multiple studies demonstrate the positive effects of high self-efficacy beliefs on patients’ arthritis symptoms and illness severity [6]. For example, patients with higher self-efficacy report experiencing less day-to-day arthritis pain [7, 8], tolerate higher intensity pain better [9], and report better physical functioning [10–13]. Higher self-efficacy is also related to improvements in arthritis symptoms over time [14–16].

Patients’ self-efficacy beliefs for managing arthritis contribute not only to their physical health but also to their mental health. For example, patients with higher self-efficacy report less psychological disability [10, 11, 13, 17], better daily mood [7, 8], and better day-to-day coping [8]. Longitudinal studies have also shown that increases in self-efficacy are associated with declines in patients’ depressive symptoms and negative affect over time [16].

Patient health may be influenced by not only patient characteristics and beliefs but also by the beliefs of close others, especially the marital partner [1, 18, 19]. Research shows that spouses influence arthritis patients’ disease management and well-being in many ways. For example, empathic responses from the spouse are associated with better symptom management and higher physical activity levels in arthritis patients [20]. In contrast, insensitive responses or unsolicited assistance is associated with worse physical functioning [21]. Furthermore, interventions in which spouses are trained to help patients cope with their arthritis have been shown to be effective, with improvements in symptoms up to 1 year after the intervention [15].

Given that spouse responses to patient symptoms have a significant impact on patient health, spouses’ beliefs with regards to patients’ efficacy in managing their condition are also likely to be important. According to social cognitive theory, partners develop beliefs about each other’s efficacy, which in turn guides whether they respond to their partner in a supportive or discouraging manner [22]. Decisions, such as how often and when to provide support and assistance (if any), are likely to be based on the partner’s sense of the patient’s competence in dealing with symptoms [18, 23]. For example, wives who had little confidence in their spouse’s ability to resume normal activities after acute myocardial infarction were more likely to inappropriately discourage their spouse from resuming their activities, resulting in lower physical fitness levels at a follow-up assessment [19]. Thus, spouse confidence in patient efficacy has implications for patients’ ability to adhere to guidelines for managing their illness, such as arthritis.

Furthermore, spouses’ beliefs in the patients' efficacy may differ from the patients’ self-efficacy, such that spouses may have more (or less) confidence in the patients’ ability to manage their illness than the patients themselves. Indeed, patients’ and spouses’ perceptions of the patients’ efficacy to manage their illness are only moderately correlated [18, 23–25], which suggests that patients and spouses may base efficacy judgments on somewhat different sources of information that have different predictive validity for patient health outcomes. For example, patients may be more focused on their own resources and past experiences in managing arthritis when making efficacy judgments, whereas spouses may have additional sources of information or influences (e.g., relationship factors, such as their own influence on patient behavior, and observations of patient behavior) when judging their level of confidence in patient efficacy. As such, patient and spouse efficacy judgments may contribute differentially to patient health. If spouses rely on valid sources of information that patients underutilize, it is possible that spouse confidence judgments provide unique predictive power above and beyond patient self-efficacy judgments.

Although a few studies have examined the correspondence between patient and spouse ratings of patient efficacy for disease management, only one study (as far as we know) has examined the relative importance of patient and spouse efficacy beliefs in predicting patient outcomes. Rohrbaugh and colleagues [18] examined ratings of patient efficacy for disease management provided by patients and their spouses in a sample of heart failure patients. They found that both patient self-efficacy and spouse confidence in patient efficacy were associated with patient survival over a 4-year period in separate predictive models. However, in a model that included both of these predictors, only spouse confidence in patient efficacy predicted patient survival 4 years later. Thus, their results suggest that although both patient and spouse reports of patient efficacy are associated with patients’ health outcomes, spouse confidence in the patients’ ability to manage their illness provides unique predictive value over and above patient self-efficacy beliefs.

Overview: the Current Study

The goal of the current study was to examine the simultaneous influence of patients’ self-efficacy beliefs and spouses’ beliefs in patients’ efficacy on patients’ physical and mental health outcomes over time. We recruited a sample of knee osteoarthritis patients and their spouses and followed them over an 18-month period, during which efficacy beliefs regarding arthritis management and the patients’ health were assessed on three separate occasions. We examined several indicators of the patients’ health, including illness severity (i.e., pain, stiffness, physical function difficulty), perceived health, lower extremity function, and mental health (i.e., depressive symptoms). The time lag between the first two assessments was 6 months, whereas the time lag between the second and third assessment was 1 year, allowing us to examine the effects of efficacy beliefs over varying time frames.

Based on the results of prior studies [3], we expected patient arthritis self-efficacy beliefs to be concurrently associated with patient health outcomes at each time point. Similarly, we expected concurrent relations between patient health outcomes and spouse confidence in patient efficacy for arthritis management at each time point. Consistent with the findings of prior research [18], we expected that spouse confidence in patient efficacy for arthritis management would be associated with improvements in patient health outcomes over time beyond patient self-efficacy. We examined changes in patients’ health over a 6-month and a 1-year time period, but did not expect that the effects of efficacy beliefs on patient health would differ across these two time frames.

Method

Participants and Procedures

Participants were recruited for a study of couples and knee osteoarthritis (only the relevant components of the study are described; for a detailed description of the larger study, see [26]). In order to be eligible to participate in the study, patients had to be diagnosed with knee osteoarthritis by a physician and experience usual knee pain that was at least moderate in intensity. All of the patients were required to be cohabiting with a spouse or partner and be at least 50 years of age. Patients and their partners also had to be cognitively functional and free of any speech, language, or hearing problems in order to ensure the quality of the data collected. Couples were excluded from the study if the patient had a comorbid diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis or fibromyalgia, if the patient or the partner used a wheelchair or needed assistance with daily personal care activities, if the patient planned to have knee or hip surgery in the next 6 months, or if the partner also had arthritis with usual pain of at least moderate intensity.

The participants were primarily recruited from rheumatology clinics, flyers distributed at the University of Pittsburgh, and word of mouth. A total of 152 couples (N = 304) enrolled in the study (the sample includes three same-sex couples; see Table 1 for demographic information). Couples completed three in-person interviews and performance-based assessments in their homes over an 18-month time period, conducted by trained research assistants. The first interview (T1) was scheduled when the couple enrolled in the study with the first follow-up interview (T2) conducted 6 months and the second follow-up interview (T3) conducted 18 months after the couple’s first interview.

Table 1.

Summary of demographic variables for the full sample

| Variables | Patient M (SD) or % |

Spouse M (SD) or % |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 65.8 (10.0) | 65.3 (12.0) |

| Gender: male | 41.4 % | 59.2 % |

| Race: White | 86.8 % | 84.9 % |

| Years of education | 16.0 (2.0) | 15.8 (2.1) |

| Years married/in relationship | 34.7 (16.9) | N/A |

| Years have osteoarthritis | 13.9 (8.7) | N/A |

At T2, four couples dropped out of the study, and another four couples were unable to schedule the interview (but participated in the T3 follow-up). Reasons for dropping out or not being able to schedule the interview included health issues and lack of time for the interview. At T3, additional 12 couples discontinued participation in the study, primarily due to the worsening of health issues or to the research team’s inability to get in contact with the couple to schedule the session. Thus, the rate of retention in this study was high, with 94.7 % of the initial sample participating at T2 and 89.5 % at T3. In comparing couples who dropped out of the study and those who did not, we found no differences between the groups on patient self-efficacy, spouse confidence in patient efficacy, patient age, number of years patient had arthritis, patient depression, and patient arthritis severity. Patients who dropped out of the study had lower scores on perceived physical health and lower extremity function at baseline. Thus, our results with regards to these outcomes should be interpreted with more caution.

Measures

Please see Table 2 for means, standard deviations, and reliability alphas for all scales at each time point.

Table 2.

Means, standard deviations, and reliability alphas for all variables at each time point

| Time 1 |

Time 2 |

Time 3 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | α | M | SD | α | M | SD | α | |

| Patient | |||||||||

| Self-efficacy | 6.83 | 1.75 | .90 | 6.99 | 1.72 | .92 | 6.96 | 1.77 | .92 |

| Depressive symptoms | 6.57 | 5.22 | .82 | 7.02 | 5.33 | .82 | 6.86 | 5.63 | .85 |

| Arthritis severity | 59.08 | 14.80 | .94 | 55.99 | 15.86 | .95 | 56.21 | 16.38 | .95 |

| Perceived physical health | 3.20 | 0.96 | – | 3.17 | 0.96 | – | 3.24 | 0.93 | – |

| Lower extremity function | 7.41 | 2.15 | – | 7.72 | 2.27 | – | 7.67 | 2.11 | – |

| Marital quality | 4.07 | 0.63 | .85 | 4.05 | 0.59 | .75 | 4.08 | 0.53 | .71 |

| Spouse | |||||||||

| Confid. in patient efficacy | 6.59 | 1.57 | .88 | 6.55 | 1.67 | .89 | 6.72 | 1.86 | .93 |

| Marital quality | 4.05 | 0.62 | .83 | 4.00 | 0.60 | .80 | 4.03 | 0.59 | .81 |

The ranges of possible scores for the scales are as follows: self-efficacy 1–10; depressive symptoms 0–30; arthritis severity 0–96; perceived physical health1–5; lower extremity function 0–12; marital quality 0–5; confidence in patient efficacy 1–10

Patient Arthritis Management Efficacy

Patients’ confidence in managing their arthritis symptoms was measured at each time point using the arthritis self-efficacy scale [27]. The scale includes five items that assess patients’ confidence in managing their pain (e.g., “how confident are you that you can decrease your pain quite a bit?”) and six items that assess confidence in managing other arthritis-related symptoms (e.g., “how confident are you that you can deal with the frustration of arthritis?”). Each item was rated on a ten-point scale, ranging from 1 (not at all confident) to 10 (totally confident). Scores on the 11 items were averaged to create a total self-efficacy score.

Spouses were also asked to respond to the same 11 items at each time point; however, for each of the items, they indicated to what extent they were confident that their spouse (i.e., the identified patient) can manage their arthritis. For example, one of the items asked spouses to rate “how confident are you that s/he [the patient] can deal with the frustration of arthritis.” Spouses also rated each item on a ten-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all confident) to 10 (totally confident), which were averaged for analysis.

Arthritis Severity

Patients were assessed at each time point using the WOMAC [28], which assesses arthritis patients’ experiences of pain, stiffness, and physical function difficulty. Patients’ pain was assessed using five items that ask about pain experienced in different body positions over the past month (e.g., walking on a flat surface, standing upright, sitting or lying). Patients’ stiffness was assessed using two items that focus on experiences of stiffness after waking and sitting over the past month. Patients’ physical functioning difficulty was assessed using 17 items that focus on patients’ difficulty in performing different day-to-day tasks involving physical movement over the past month (e.g., going up a flight of stairs, rising from bed). All items were rated on five-point scales ranging from 0 (none) to 4 (extreme). Scores were summed to create an overall arthritis severity score (range 0 to 96).

Depressive Symptomatology

Patients’ depressive symptomatology was assessed at each of the three time points using the short form of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies–Depression (CES-D) scale [29]. This scale consists of ten items that assess depressive symptoms over the past week on four-point scales ranging from 0 (rarely or none of the time, less than 1 day) to 3 (most of the time, 5– 7 days). Scores on the items were summed to create a total depressive symptomatology score (range 0 to 30).

Perceived Health

At each time point, patients’ perceived overall health was assessed using a single item (modified from [30]). The item asked “in general, would you say your health is” with five response options, ranging from 1 (poor) to 5 (excellent).

Lower Extremity Function

At each time point, patients were asked to complete a short physical performance battery that assesses lower extremity function in older adults [31]. This battery includes three different tests. The first is a test of standing balance, where people complete tasks of increasing difficulty (i.e., side-by-side stand, semi-tandem stand, and tandem stand). The second is a test of gait speed, where people are asked to walk 4 m in their normal walking speed and repeat the task again to get a more accurate assessment of their gait speed. The third test involves chair rises, where the person is first asked to stand up from a seated position without using their hands for assistance. If they can stand up, they are next asked to stand up from a chair five times, which is timed. Each of the three tests was scored on a five-point scale (ranging from 0 to 4), with higher scores representing better physical performance. Scores on the three tests were summed to create an overall score of physical performance (range 0 to 12). Guralnik and colleagues [31] reported average scores of 7.12 with a sample of more than 5,000 older adults (age 65 and older), which is comparable to our sample average of 7.41 at T1, given our slightly younger sample.

Marital Quality

Patients and spouses also completed a measure of marital quality at each time point, using the satisfaction subscale of the Dyadic Adjustment Scale [32]. This subscale consists of seven items that assess the occurrence of relationship behaviors that indicate the overall quality of the relationship (e.g., “How often do you and your spouse quarrel?”). Items were rated on six-point scales ranging from 0 (all the time) to 5 (never) and were averaged for analysis, with higher scores indicating greater relationship quality.

Data Analysis Plan

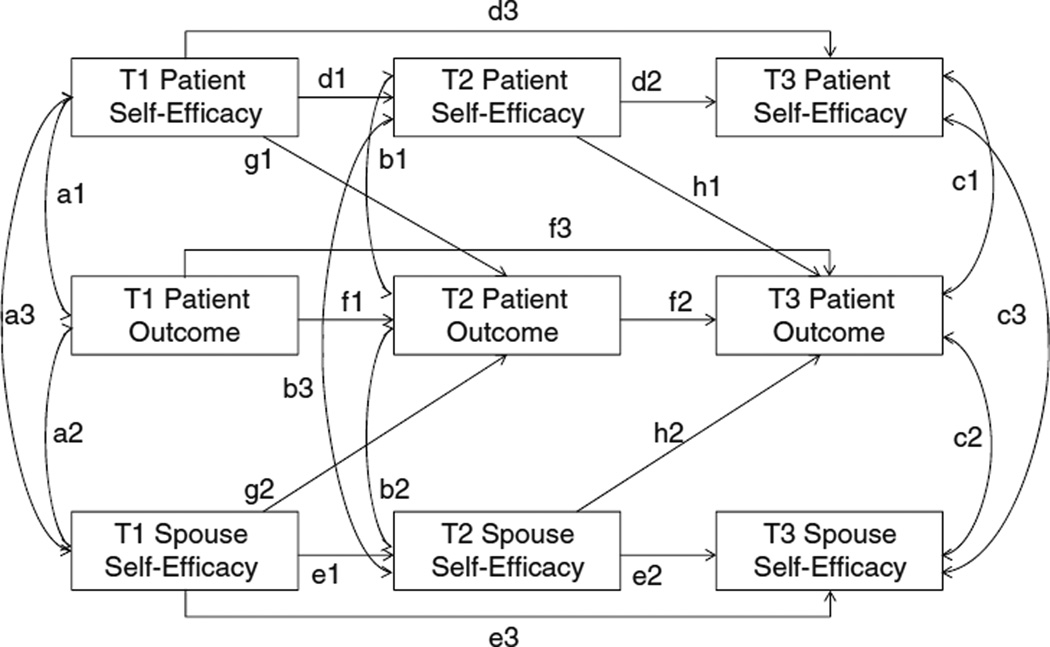

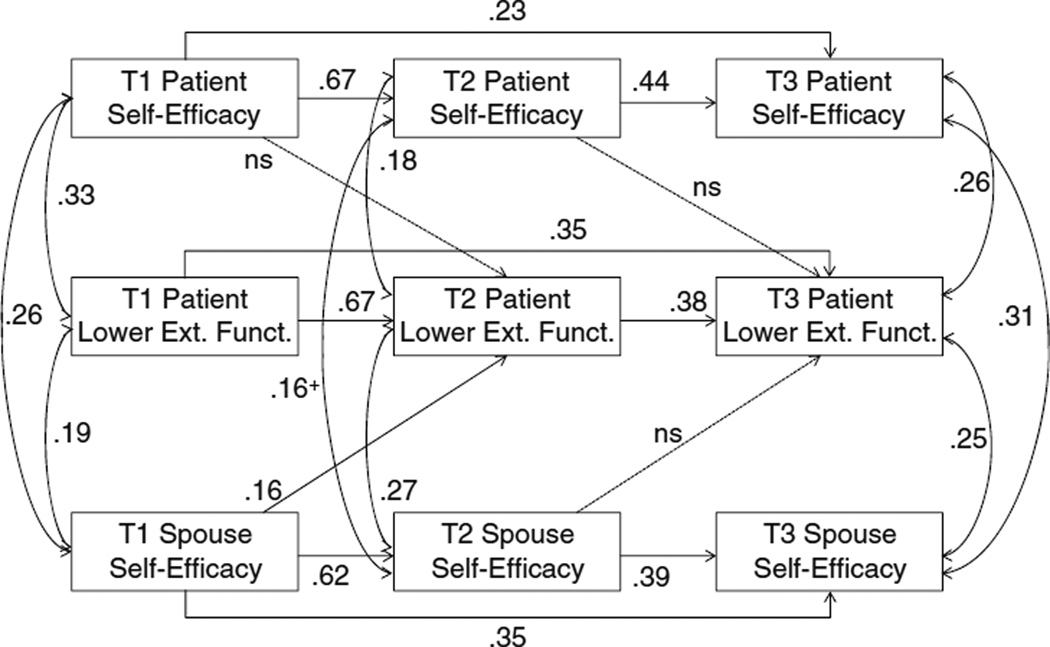

We examined the effects of patient and spouse efficacy beliefs on patient outcomes over time, using path analyses with the software MPlus [33]. The full model tested for each outcome is shown in Fig. 1. In each analysis, variances for exogenous variables and residual terms for endogenous variables were estimated, and covariation between patient self-efficacy, spouse confidence in patient efficacy, and patient outcome at concurrent time points was also estimated (paths a1, a2, a3 are covariances at time 1; paths b1, b2, b3 are residual covariances at time 2; paths c1, c2, c3 are residual covariances at time 3). Each construct was also regressed on the measures of the same construct at earlier time points to account for stability of the construct over time (paths d1, d2, d3 for patient self-efficacy stability; paths e1, e2, e3 for stability in spouse confidence in patient efficacy; paths f1, f2, f3 for stability of the patient outcome), which represent first-order and second-order autoregressive effects (i.e., effects between subsequent time points and effects between time points one step apart, respectively).

Fig. 1.

Path model tested in analysis for each patient outcome

Finally, central to our research question, we tested whether patient and spouse efficacy beliefs for arthritis management predict changes in patient outcomes over time (paths g1 and g2 test changes between time 1 and time 2; paths h1 and h2 test changes between time 2 and time 3). It is important to keep in mind that our tests of these longitudinal associations are very conservative, given that we simultaneously control for stability in constructs over time, as well as concurrent relations between the constructs. If any of the g or h paths are significant, this indicates that unique variance in efficacy beliefs at an earlier time point (i.e., variance that is no longer present at the subsequent time point) predicts unique variance in patient outcomes at a later time point (i.e., unique variance that was not present at the earlier time point and cannot be accounted for by concurrent efficacy beliefs).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

We first examined the correlations between patient and spouse ratings of patient efficacy for arthritis management at each time point. Consistent with prior research [18, 23–25], patients’ self-efficacy ratings were only moderately correlated with spouse confidence in patient efficacy at all three time points (r=.28 to .34). We also examined whether patients and spouses rated patient efficacy for arthritis management differently at each of the time points using paired-samples t tests. There were no differences in patient and spouse ratings of patient efficacy at T1 and T3; however, at T2, patients’ ratings of self-efficacy (M=6.99, SD=1.72) were significantly higher than spouse ratings of patient efficacy (M=6.55, SD=1.67), t (142)=2.71, p=.008.

Next, we tested the association between patient gender and patient efficacy ratings, as well as the influence of gender in our models. First, we examined whether patient self-efficacy ratings and ratings of spouse confidence in patient efficacy differed based on patient gender. Patient gender was not a significant predictor either of patient self-efficacy or spouse confidence in patient efficacy at any of the time points (all p’s>.10). Second, we re-ran our main analyses by estimating concurrent and longitudinal relations between ratings of patient efficacy and patient outcomes separately by patient gender. We then compared the confidence intervals (CI) for men and women for each estimate in each model. Out of a total of 40 estimates, none of the longitudinal associations and only two concurrent associations indicated a significant gender difference (i.e., the confidence intervals of men and women did not overlap). Given the overall lack of evidence for gender differences and to preserve sufficient power to conduct our main analyses, we present the main results for male and female patients combined. All of our analyses control for the number of years the patient has had arthritis. Our analyses were also re-run with marital quality controlled and with controls for the reverse longitudinal paths of the influence of patient outcomes on patient and spouse efficacy beliefs.

Main Analyses

For each analysis, we present the overall data fit indices, the fully standardized estimates of the significant paths, their standard errors (SE), and their associated 95 % confidence intervals. When the confidence interval does not include zero as a value, the estimate is statistically significant at p<.05. For estimates that were marginally significant (p<.10), we also provide exact p values. The standardized estimates can be directly interpreted as effect sizes, as squaring the standardized estimate of an effect corresponds to the amount of variance explained.

We found that there was significant stability over time in each construct. The estimates of stability coefficients are provided for each construct in Figs. 2, 3, 4, and 5. Furthermore, at each time point, patient self-efficacy was concurrently associated with spouse confidence in patient efficacy (at T2, in some cases this association was marginally significant at p=.06). These estimates are also provided in each figure. We focus our description of the results on the concurrent associations between efficacy beliefs and the patients’ health outcomes, as well as on the prediction of change in patient outcomes over time from efficacy beliefs (see Table 3 for the zero-order correlations between all constructs at each time point).

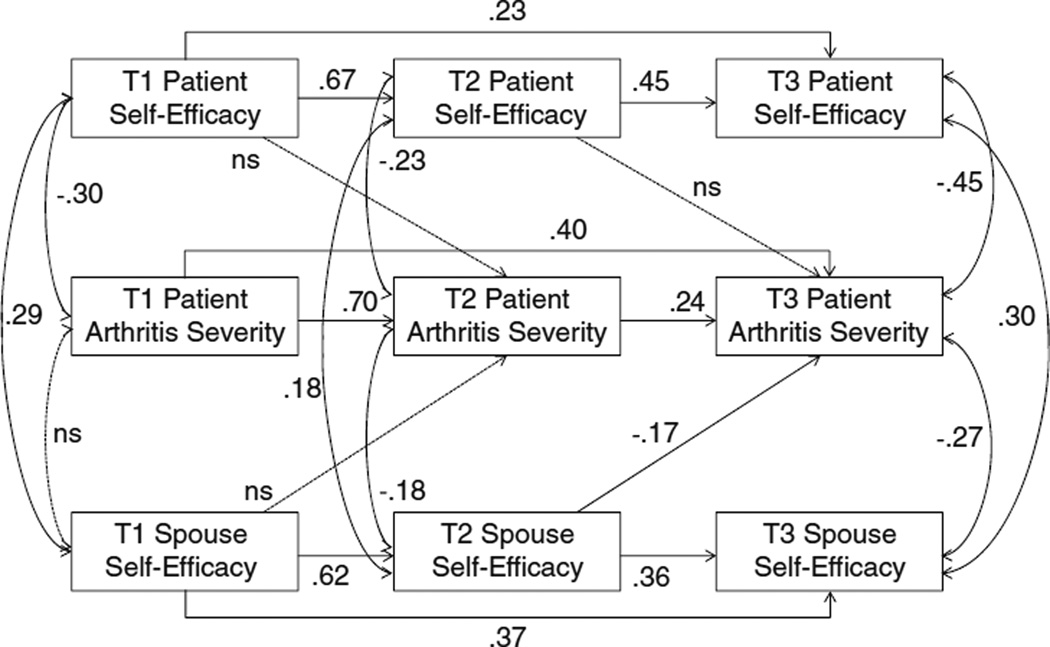

Fig. 2.

Final model showing patients’ experiences of arthritis severity over time with fully standardized estimates. Note: All paths with solid lines are statistically significant at p<.05. Dotted lines are not statistically significant. NS non-significant

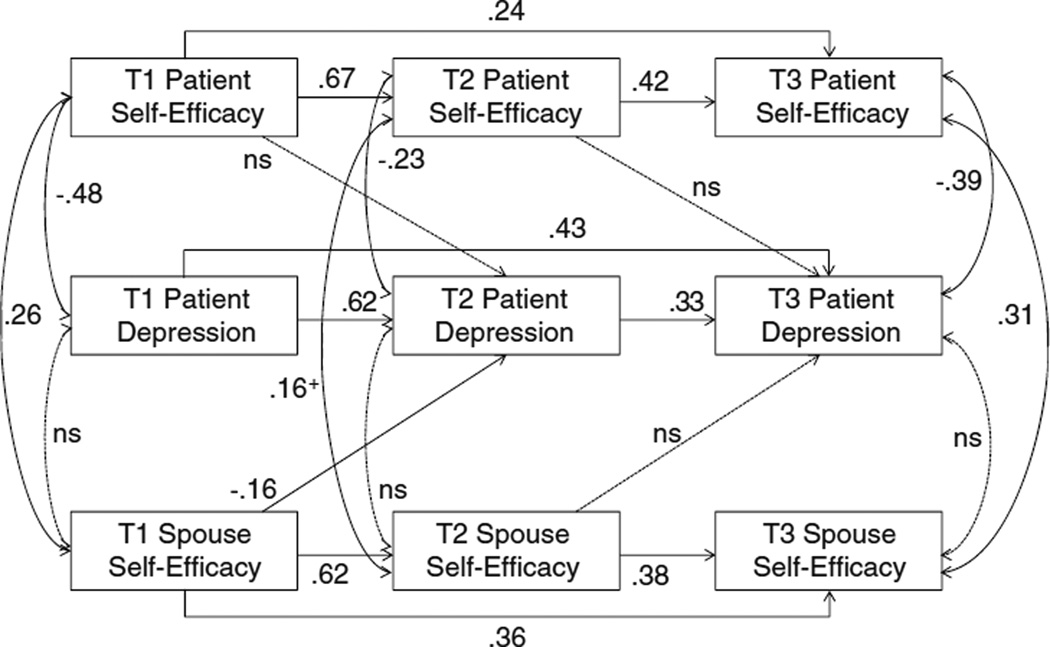

Fig. 3.

Final model showing patients’ depressive symptoms over time with fully standardized estimates. Note: Paths with solid lines are statistically significant at p<.05 or at p<.10 if marked with plus sign. Dotted lines are not statistically significant. NS non-significant

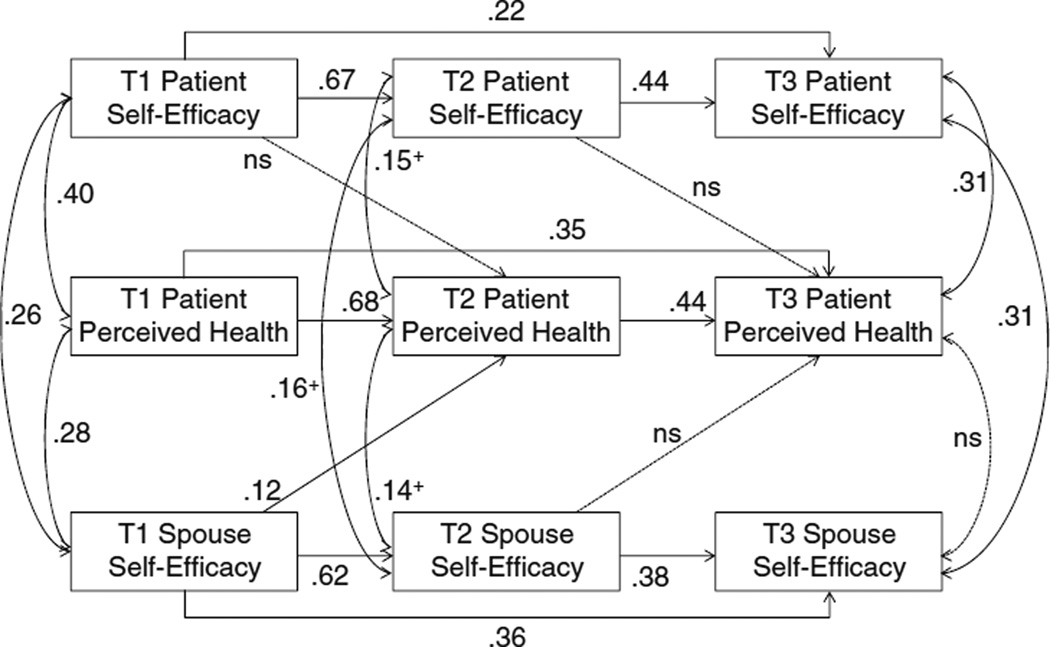

Fig. 4.

Final model showing patients’ perceived health over time with fully standardized estimates. Note: Paths with solid lines are statistically significant at p<.05 or at p<.10 if marked with plus sign. Dotted lines are not statistically significant. NS non-significant

Fig. 5.

Final model showing patients’ lower extremity function over time with fully standardized estimates. Note: Paths with solid lines are statistically significant at p<.05 or at p<.10 if marked with plus sign. Dotted lines are not statistically significant. NS non-significant

Table 3.

Zero-order correlations between all variables at all three time points

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Pt. SE T1 | |||||||||||||||||

| 2. Pt. SE T2 | .70 | ||||||||||||||||

| 3. Pt. SE T3 | .53 | .64 | |||||||||||||||

| 4. Sp. E T1 | .28 | .25 | .14+ | ||||||||||||||

| 5. Sp. E T2 | .33 | .34 | .29 | .63 | |||||||||||||

| 6. Sp. E T3 | .18 | .25 | .34 | .59 | .60 | ||||||||||||

| 7. Pt. AS T1 | −.38 | −.34 | −.25 | −.30 | −.38 | −.26 | |||||||||||

| 8. Pt. AS T2 | −.36 | −.38 | −.26 | −.31 | −.40 | −.35 | .73 | ||||||||||

| 9. Pt. AS T3 | −.25 | −.27 | −.43 | −.24 | −.40 | −.44 | .58 | .52 | |||||||||

| 10. Pt. Dep. T1 | −.50 | −.43 | −.46 | −.10+ | −.20 | −.16+ | .41 | .37 | .34 | ||||||||

| 11. Pt. Dep. T2 | −.45 | −.49 | −.48 | −.27 | −.32 | −.29 | .40 | .39 | .39 | .70 | |||||||

| 12. Pt. Dep. T3 | −.43 | −.45 | −.60 | −.07+ | −.22 | −.23 | .24 | .19 | .39 | .73 | .70 | ||||||

| 13. Pt. PH T1 | .41 | .44 | .42 | .30 | .29 | .30 | −.41 | −.38 | −.27 | −.48 | −.47 | −.42 | |||||

| 14. Pt. PH T2 | .36 | .45 | .49 | .36 | .36 | .37 | −.37 | −.39 | −.32 | −.43 | −.52 | −.48 | .76 | ||||

| 15. Pt. PH T3 | .38 | .43 | .54 | .34 | .31 | .34 | −.31 | −.29 | −.33 | −.47 | −.46 | −.49 | .73 | .77 | |||

| 16. Pt. LEF T1 | .35 | .34 | .36 | .22 | .19 | .17 | −.42 | −.44 | −.28 | −.31 | −.27 | −.28 | .39 | .26 | .29 | ||

| 17. Pt. LEF T2 | .31 | .39 | .37 | .31 | .34 | .26 | −.38 | −.45 | −.26 | −.29 | −.30 | −.27 | .35 | .30 | .28 | .72 | |

| 18. Pt. LEF T3 | .24 | .26 | .39 | .26 | .21 | .32 | −.28 | −.36 | −.26 | −.18 | −.27 | −.27 | .34 | .36 | .29 | .59 | .58 |

All correlations are significant at p<.05, except those marked with +

Pt. patient, Sp. spouse, SE self-efficacy, E efficacy beliefs, AS arthritis severity, Dep. depressive symptoms, PH perceived health, LEF lower extremity function

We found strong support for our hypothesis that spouse confidence in patient efficacy for arthritis management would predict improvements in patient health over time beyond the effects of patient self-efficacy. These effects emerged most frequently across the 6-month period between T1 and T2. In the case of arthritis severity, we found evidence of longitudinal effects across the longer, 1-year time period between T2 and T3. We describe the findings in more detail for each outcome below.

First, we examined predictors of change in arthritis severity over the 18 months of the study (see Fig. 2). Our model fit the data well, χ2 (14) = 18.98, p=.17, comparative fit index (CFI) = .992, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) = .049, standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) = .043. The results indicated that higher patient self-efficacy was associated with less arthritis severity concurrently at each time point (T1: β=−.30, SE=.07, CI=−.44 to −.15; T2: β=−.23, SE=.08, CI=−.39 to −.07; T3: β=−.45, SE=.07, CI=−.59 to −.31). Patient self-efficacy did not predict change in arthritis severity over time. Spouse confidence in patient efficacy was concurrently associated with less arthritis severity at T2 and T3 (T2: β=−.18, SE=.08, CI=−.34 to −.02; T3: β=−.27, SE=.08, CI=−.43 to −.11), but not at T1 (T1: β= −.08, SE=.08, CI=−.24 to .08). Consistent with our hypothesis, spouse confidence in patient efficacy predicted decreased patient arthritis severity from T2 to T3 (β=−.17, SE=.07, CI= −.30 to −.03) beyond the effects of patient self-efficacy. Spouse confidence in patient efficacy did not predict changes in patient arthritis severity over the shorter time period from T1 to T2.

We examined predictors of change in patient depressive symptoms over time next (see Fig. 3). Our model fit the data well, χ2 (14) = 19.94, p=.13, CFI=.991, RMSEA=.053, SRMR=.049. The results indicated that patient self-efficacy was associated with fewer depressive symptoms concurrently at each time point (T1: β=−.48, SE=.06, CI=−.60 to −.36; T2: β=−.23, SE=.08, CI=−.39 to −.08; T3: β=−.39, SE=.07, CI=−.54 to −.25). Patient self-efficacy did not predict changes in depressive symptoms over time. Spouse confidence in patient efficacy was not associated with patient depressive symptoms concurrently. Spouse confidence in patient efficacy predicted decreased patient depressive symptoms from T1 to T2 (β=−.16, SE=.06, CI=−.28 to −.04) beyond the effects of patient self-efficacy, but not from T2 to T3.

Next, we examined predictors of change in patient perceived health over time (see Fig. 4). Our model fit the data well, χ2 (14)=28.76, p=.011, CFI=.978, RMSEA=.083, SRMR=.062. Results showed that patient self-efficacy was associated with better perceived health concurrently at each time point (T1: β=.40, SE=.07, CI=.26 to .53; T2: β=.15, SE=.09, CI=−.02 to .31, p=.086; T3: β=.31, SE=.08, CI=.15 to .47), although the association was marginal at T2 (p=.086). Patient self-efficacy did not predict changes in perceived health over time. Spouse confidence in patient efficacy was associated with greater patient perceived health concurrently at T1 and marginally at T2 (T1: β=.28, SE=.08, CI=.13 to .42; T2: β=.14, SE=.08, CI=−.02 to .30, p=.090), but not at T3. Spouse confidence in patient efficacy predicted increases in patient perceived health from T1 to T2, as predicted (β=.12, SE=.06, CI=.002 to .24) beyond the effects of patient self-efficacy, but not from T2 to T3.

Finally, we examined predictors of change in patient lower extremity function over time (see Fig. 5). Our model fit the data well, χ2 (14)=18.01, p=.21, CFI=.993, RMSEA=.043, SRMR=.045. The results indicated that higher patient self-efficacy was associated with better lower extremity function concurrently at each time point (T1: β=.33, SE=.07, CI=.18 to .47; T2: β=.18, SE=.09, CI=.01 to .35; T3: β=.26, SE=.09, CI=.08 to .44). Patient self-efficacy did not predict changes in lower extremity function over time. Spouse confidence in patient efficacy was concurrently associated with greater patient lower extremity function at each time point (T1: β=.19, SE=.08, CI=.04 to .34; T2: β=.27, SE=.08, CI=.11 to .43; T3: β=.25, SE=.09, CI=.08 to .42). Furthermore, spouse confidence in patient efficacy predicted increases in patient lower extremity function from T1 to T2 (β=.16, SE=.06, CI=.04 to .28), as predicted, but not from T2 to T3.

We repeated all of our analyses controlling for marital quality. When controlling for either patient or spouse marital quality, all of our results remained unchanged. We also repeated our analyses controlling for the influence of patient outcomes on patient and spouse efficacy beliefs over time. The inclusion of these paths did not change our results.

Discussion

In the current study, we examined concurrent and longitudinal associations of patient self-efficacy and spouse confidence in patient efficacy with patient health outcomes. Consistent with prior research on heart failure patients that examined the simultaneous effects of patient efficacy and spouse confidence in illness management [18], we found that spouse confidence in patient efficacy predicted changes in patient health over time beyond the effects of patient self-efficacy. More specifically, spouse confidence in patient efficacy for arthritis management was associated with improvements in patient arthritis severity over a 1-year period and with improvements in patient depressive symptoms, perceived health, and lower extremity function over 6 months. Patient self-efficacy, however, did not predict changes in patient health.

Prior research has provided strong evidence that patient self-efficacy beliefs are important for maintaining mental and physical health [3, 14–16, 19]. Consistent with this literature, we also found that patient self-efficacy beliefs were concurrently associated with better physical and mental health. At each of the three time points, patients who had greater confidence in their ability to manage their arthritis experienced less arthritis severity, better health, and fewer depressive symptoms. Patient self-efficacy was also associated with patient health across time at the bivariate level. However, when simultaneously considering the effects of spouse confidence in patient efficacy, patient self-efficacy did not predict changes in health. These findings are consistent with the work of Rohrbaugh and colleagues [18].

It is important to note that our statistical approach provided a very stringent test of whether self-efficacy at an earlier time point can predict changes in health outcomes over time. In our analyses, we controlled for stability in the constructs over time, concurrent relations between self-efficacy and health outcomes at all time points, and spouse confidence in patient efficacy. Given the high level of stability in both patient health and self-efficacy, we may not have been able to detect any longitudinal effects of self-efficacy on health outcomes, which are likely to be small in magnitude. In future research examining prospective effects of self-efficacy for illness management, it would be useful to control for both stability and concurrent associations in constructs at each time point, in order to determine whether unique variance in self-efficacy at an earlier time point can predict changes in health over time.

Prior research has shown that patients’ self-efficacy beliefs regarding illness management are only moderately correlated with their spouses’ confidence in their efficacy [18, 23–25], which is consistent with our data. This moderate association supports the possibility that patient and spouse ratings of efficacy are differentially related to health outcomes. However, despite the moderate correlations, it does not seem to be the case that patient efficacy levels are rated differently by patients and spouses as a group. At T1 and T3, there were no differences between patient and spouse ratings of patient efficacy levels. Some studies have also found that patient efficacy levels are rated similarly by patients and spouses [23–25], whereas other work suggests that patient self-efficacy tends to be higher than spouse confidence in patient efficacy [18, 19], which is consistent with the differences we found at T2. Although the discrepancy between patients’ and spouses’ perceptions was not the focus of the current paper, in future research, it will be important to examine the potential consequences of discrepancies between partners’ perceptions.

The results of our longitudinal analyses suggest that spouse confidence in patient efficacy for arthritis management plays an important role in patient health beyond the effects of patient self-efficacy. We found that spouse confidence in patient efficacy prospectively predicted improvements in the patients’ health over time, even with our stringent analysis method that controlled for construct stability, concurrent associations, and the effects of patient self-efficacy. Spouse confidence predicted improvements in patient depressive symptoms, perceived health, and lower extremity function over the 6-month period and improvements in arthritis severity over the 1-year period. It is important to note that lower extremity function was assessed in the study through performance on a variety of physical tests. That is, our findings hold for an important objective measure of health that is associated with subsequent disability in activities of daily living [31] as well as survival [34]. Increases in lower extremity function suggest that spouse confidence enabled patients to gain improvements in physical functioning that are necessary to be able to perform everyday tasks. As such, patients who have spouses that believe in their ability to manage their condition are likely able to maintain an active lifestyle for a longer period of time and delay the onset of disability.

An important next step in this area of research will be to identify mechanisms through which spouse confidence exerts its effects on patient health. Perhaps, whether a spouse believes that the patient is able to cope with illness effectively influences their reaction to the patient’s condition and the type of assistance they offer [18, 23]. When spouses do not believe that patients can deal with their condition competently, they may provide more support than needed and unintentionally make it difficult for patients to stay physically active and engaged in self-management [19, 23]. In contrast, when spouses believe that patients are capable of managing their condition, they may provide encouragement and support [18, 19, 23]. However, some work suggests that the effects of spouse confidence on patient health are independent of any effects of the support received by the patient from their spouse [24]. Thus, additional work is needed to improve understanding of the associations between spouse confidence, patient health, and spousal support.

It has also been suggested that spouse confidence in patient efficacy for disease management may serve as a proxy for relationship quality, and thus, the association between spouse confidence and patient health reflects that patients with spouses who believe in their efficacy have better marriages [18]. In a prior study of patients with congestive heart failure, Rohrbaugh and colleagues [18] found that including relationship quality in their model substantially weakened the effects of spouse confidence on patient survival. This was not the case in our study, as controlling for patient or spouse marital quality did not change our findings. Given the scarcity of research on the influence of spouse confidence in patient efficacy, at this point, it is difficult to know how the quality of the couple relationship plays into the effects of spouse confidence on patient health.

The effects of spouse confidence on patient health were observed more frequently in our study over the 6-month time period than over the 12-month time period. Thus, it is possible that these longitudinal effects are stronger over relatively shorter time frames than over several years. However, Rohrbaugh and colleagues [18] found effects of spouse confidence on patient survival over a 4-year period, which is a considerably longer time period than in our study. At this point, it is unclear why we found effects primarily during the shorter time period and not during the longer time period. The ability to detect longitudinal effects over long time periods may substantially depend on the type of outcome examined, the sample size, and the conservativeness of the statistical analysis. In the future, the time frame of these effects on different types of health outcomes should be examined to provide a better understanding of the influence of spouses’ beliefs on the health of patients.

It is important to note that our sample of patients with knee osteoarthritis is quite distinct from other samples in which the effects of spouse confidence in patient efficacy have been examined. Prior studies have shown that spouse confidence in patient efficacy for disease management contributes to patient health in samples of patients who experienced myocardial infarction [19], congestive heart failure [18], and stroke [24]. Thus, the results of our own and others’ work suggest that spouse confidence is an important predictor of patient health in a variety of patient populations where disease management is ongoing in patients’ lives. Future work with other patient populations would be important to further extend the generalizability of the existing findings.

Our findings may have implications for developing interventions for arthritis patients that involve their spouses [35–37]. Earlier work with acute myocardial infarction patients shows that an intervention that enhanced spouses’ confidence in patients’ ability to increase physical activities, by having spouses perform treadmill exercises themselves, was effective in improving patient treadmill performance [19]. Spouses who have confidence in their spouses’ ability to engage in physical activity safely may encourage patients to take on more physically challenging tasks that improve their physical endurance and health over time. Thus, enhancing spouse confidence in patient efficacy may be an effective strategy in couple-oriented interventions.

In sum, the results of this study show that spouse confidence in patient efficacy to manage arthritis was associated with improvements in patient health over time beyond the effects of patient self-efficacy and that both spouse confidence and patient self-efficacy were important for concurrent patient well-being. These results underscore the importance of considering the influence of close relationships on the health and well-being of the growing population of adults with knee OA. We hope that our work will stimulate further research on the mechanisms and time frame of spousal influence and on other patient populations. Through more research, enhancing spouse confidence in patient efficacy may turn out to be an important component of couple-oriented interventions to improve patient health.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by a grant from the National Institutes for Health (R01 AG026010).

Footnotes

Authors’ Statement of Conflict of Interest and Adherence to Ethical Standards Authors Gere, Martire, Keefe, Stephens, and Schulz declare that they have no conflict of interest. All procedures, including the informed consent process, were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000.

Contributor Information

Judith Gere, Email: jgere@kent.edu, Kent State University, Kent, OH, USA; Department of Psychology, Kent State University, 211 Kent Hall, Kent, OH 44242, USA.

Lynn M. Martire, Penn State University, State College, PA, USA

Francis J. Keefe, Duke University, Durham, NC, USA

Mary Ann Parris Stephens, Kent State University, Kent, OH, USA

Richard Schulz, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA

References

- 1.Keefe FJ, Smith SJ, Buffington ALH, Gibson J, Studts JL, Caldwell DS. Recent advances and future directions in the biopsychosocial assessment and treatment of arthritis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2002;70:640–655. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.3.640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murphy L, Schwartz TA, Helmick CG, et al. Lifetime risk of symptomatic knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2008;59:1207–1213. doi: 10.1002/art.24021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keefe FJ, Somers TJ. Psychological approaches to understanding and treating arthritis pain. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010;6:210–216. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bandura A. Self-efficacy—toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84:191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bandura A. Self-efficacy. In: Ramachaudran VS, editor. Encyclopedia of human behavior. Vol. 4. New York: Academic Press; 1994. pp. 71–81. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Somers TJ, Keefe FJ, Godiwala N, Hoyler GH. Psychosocial factors and the pain experience of osteoarthritis patients: New findings and new directions. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2009;21:501–506. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e32832ed704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keefe FJ, Affleck G, Lefebvre JC, Starr K, Caldwell DS, Tennen H. Pain coping strategies and coping efficacy in rheumatoid arthritis: A daily process analysis. Pain. 1997;69:35–42. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(96)03246-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lefebvre JC, Keefe FJ, Affleck G, et al. The relationship of arthritis self-efficacy to daily pain, daily mood, and daily pain coping in rheumatoid arthritis patients. Pain. 1999;80:425–435. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(98)00242-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Keefe FJ, Lefebvre JC, Maixner W, Salley AN, Caldwell DS. Self-efficacy for arthritis pain: Relationship to perception of thermal laboratory pain stimuli. Arthritis Care Res. 1997;10:177–184. doi: 10.1002/art.1790100305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pells JJ, Shelby RA, Keefe FJ, et al. Arthritis self-efficacy and self-efficacy for resisting eating: Relationships to pain, disability, and eating behavior in overweight and obese individuals with osteoarthritic knee pain. Pain. 2008;136:340–347. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shelby RA, Somers TJ, Keefe FJ, Pells JJ, Dixon KE, Blumenthal JA. Domain specific self-efficacy mediates the impact of pain catastrophizing on pain and disability in overweight and obese osteoarthritis patients. Journal of Pain. 2008;9:912–919. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Somers TJ, Shelby RA, Keefe FJ, et al. Disease severity and domain-specific arthritis self-efficacy: Relationships to pain and functioning in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2010;62:848–856. doi: 10.1002/acr.20127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Turner JA, Ersek M, Kemp C. Self-efficacy for managing pain is associated with disability, depression, and pain coping among retirement community residents with chronic pain. Journal of Pain. 2005;6:471–479. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2005.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brekke M, Hjortdahl P, Kvien TK. Changes in self-efficacy and health status over 5 years: A longitudinal observational study of 306 patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis & Rheumatism-Arthritis Care & Research. 2003;49:342–348. doi: 10.1002/art.11112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keefe FJ, Caldwell DS, Baucom D, et al. Spouse-assisted coping skills training in the management of knee pain in osteoarthritis: Long-term followup results. Arthritis Care Res. 1999;12:101–111. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199904)12:2<101::aid-art5>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smarr KL, Parker JC, Wright GE, et al. The importance of enhancing self-efficacy in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 1997;10:18–26. doi: 10.1002/art.1790100104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keefe FJ, Rumble ME, Scipio CD, Giordano LA, Perri LM. Psychological aspects of persistent pain: Current state of the science. Journal of Pain. 2004;5:195–211. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2004.02.576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rohrbaugh MJ, Shoham V, Coyne JC, Cranford JA, Sonnega JS, Nicklas JM. Beyond the “self in self-efficacy: Spouse confidence predicts patient survival following heart failure. J Fam Psychol. 2004;18:184–193. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.1.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taylor C, Bandura A, Ewart C, Miller N, Debusk R. Exercise testing to enhance wives confidence in their husbands cardiac capability soon after clinically uncomplicated acute myocardial-infarction. Am J Cardiol. 1985;55:635–638. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(85)90127-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharma L, Cahue S, Song J, Hayes K, Pai YC, Dunlop D. Physical functioning over three years in knee osteoarthritis—role of psychosocial, local mechanical, and neuromuscular factors. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:3359–3370. doi: 10.1002/art.11420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Martire LM, Stephens MAP, Schulz R. Independence centrality as a moderator of the effects of spousal support on patient well-being and physical functioning. Health Psychol. 2011;30:651–655. doi: 10.1037/a0023006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lent RW, Lopez FG. Cognitive ties that bind: A tripartite view of efficacy beliefs in growth-promoting relationships. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2002;21:256–286. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Keefe FJ, Kashikar-Zuck S, Robinson E, et al. Pain coping strategies that predict patients’ and spouses’ ratings of patients’ self-efficacy. Pain. 1997;73:191–199. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(97)00109-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Molloy GJ, Johnston M, Johnston DW, et al. Spousal caregiver confidence and recovery from ambulatory activity limitations in stroke survivors. Health Psychol. 2008;27:286–290. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.27.2.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Porter LS, Keefe FJ, McBride CM, Pollak K, Fish L, Garst J. Perceptions of patients’ self-efficacy for managing pain and lung cancer symptoms: Correspondence between patients and family caregivers. Pain. 2002;98:169–178. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00042-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martire LM, Stephens MAP, Mogle JA, Schulz R, Brach J, Keefe FJ. Daily spousal influence on physical activity in knee osteoarthritis. Ann Behav Med. 2013;45:213–223. doi: 10.1007/s12160-012-9442-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lorig K, Chastain RL, Ung E, Shoor S, Holman HR. Development and evaluation of a scale to measure perceived self-efficacy in people with arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1989;32:37–44. doi: 10.1002/anr.1780320107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bellamy N, Buchanan W, Goldsmith C, Campbell J, Stitt L. Validation-study of WO MAC—a health-status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug-therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol. 1988;15:1833–1840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andersen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, Patrick DL. Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale) Am J Prev Med. 1994;10:77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosinski M, Gandek B. SF-36 Health Survey Manual and Interpretation Guide. Boston, MA: Nimrod Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Simonsick EM, Salive ME, Wallace RB. Lower-extremity function in persons over the age of 70 years as a predictor of subsequent disability. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:556–561. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503023320902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Spanier GB. Measuring dyadic adjustment: New scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. J Marriage Fam. 1976;38:15–28. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muthén L, Muthén B. MPlus 5. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Studenski SPS. Gait speed and survival in older adults. JAMA. 2011;305:50–58. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martire LM. Couple-oriented interventions for chronic illness: Where do we go from here? J Soc Pers Relat. 2013;30:207–214. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martire LM, Schulz R. Involving family in psychosocial interventions for chronic illness. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2007;16:90–94. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martire LM, Schulz R, Helgeson VS, Small BJ, Saghafi E. Review and meta-analysis of couple-oriented interventions for chronic illness. Ann Behav Med. 2010;40:325–342. doi: 10.1007/s12160-010-9216-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]