Abstract

Assessment of γH2AX expression for studying DNA double-strand break formation is often performed by manual counting of foci using immunofluorescence microscopy, an approach that is laborious and subject to significant foci selection bias. Here we present a novel high-throughput method for detecting DNA double-strand breaks using automated image cytometry assessment of cell average γH2AX immunofluorescence. Our technique provides an expedient, high-throughput, objective, and cost-effective method for γH2AX analysis.

Keywords: image cytometry, DNA, double-strand breaks, γH2AX

DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) occur naturally as part of normal cell development, are induced by ionizing radiation, or can be generated by chemotherapeutic agents. DSBs scale linearly with ionizing radiation dose, with an incidence of approximately 20–40 DSBs per Gy of absorbed dose per nucleus from X-rays (1, 2). A commonly utilized surrogate for DSB formation is the phosphorylation of histone H2AX at Serine 139 (γH2AX), which is one of the first steps in the initiation of the cellular DNA DSB repair pathway (2–4). Resolution of DSBs correlates with dephosphorylation of γH2AX. The time course of phosphorylation and dephosphorylation can be measured to determine the kinetics of repair. Traditionally, this process is analyzed by counting the number of γH2AX foci via immunofluorescence microscopy, assessing levels of γH2AX by Western blot, or determining the level of per cell γH2AX by flow cytometry (5). All of these methods are both labor- and time-intensive and can have significant costs associated with them (Table 1). Manual foci counting is also susceptible to foci selection bias by the investigator. Here we present an expedient, high-throughput, objective, and cost-effective method for γH2AX analysis.

Table 1.

Comparison of γH2AX analysis methods.

| Analysis method | Readout | Sensitivity | Time | Sample prep cost | Instrument cost | # cells analyzed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Image cytometry | Per cell average intensity | 2+ | 1+ | 2+ | 3+ | 100–20,000 |

| Western blot | Specimen average | 1+ | 2+ | 1+ | 1+ | 100,000–1,000,000 |

| Immunofluorescence microscopy | Per cell foci | 3+ | 3+ | 2+ | 2+ – 3+ | 10–100 |

| Flow cytometry | Per cell average intensity | 2+ | 2+ | 3+ | 3+ – 3+ | 5000–10,000 |

| Imagestream flow cytometry | Per cell foci | 3+ | 3+ | 3+ | 4+ | 5000–10,000 |

Common methods utilized for analysis of γH2AX are compared across a range of use parameters. An arbitrary scale of 1+ (low) to 4+ (high) is used.

Cells are first cultured in flat-bottom 96-well plates and differentially irradiated in groups of 4 wells (for sample replicates) using a high-throughput variable dose-rate irradiator we described previously (6). Following radiation, cells are either immediately assayed to assess maximal γH2AX response or assayed at later time points to assess DNA repair kinetics. Additionally, this method may be easily adapted to assess γH2AX foci induced by chemotherapeutic agents. At the desired time point, medium is aspirated from each well, and cells are fixed in a volume of 50 µL/well of 4% formaldehyde (methanol free) in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4, for 10 min at 37°C and then chilled on ice for 1 min. Fixative is aspirated from each well, and cells are washed 3 times with PBS (100 µL/well). Cells are then permeabilized using 90% methanol (in PBS, 50 µL/well) for 30 min on ice. Cells are again washed 3 times with PBS (100 µL/well). Nonspecific antibody binding is blocked by incubating cells in incubation buffer (100 µL/well, 0.5 g BSA in 100 mL PBS) for 10 min at room temperature. Buffer is aspirated, and cells are incubated with 50 µL/well Phospho-Histone H2A.X (Ser 139) (20E3) Rabbit MAb primary antibody (#9718, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) at a 1:400 concentration, diluted in incubation buffer at room temperature for 1 h.

Cells are washed 3 times (100 µL/ well) with antibody-free incubation buffer. Cells are then incubated with 50 µL/well of a fluorescently conjugated (Alexa Fluor 488) secondary anti-rabbit IgG (#4412, Cell Signaling Technology) diluted 1:1000 in incubation buffer for 30 min at room temperature. During this incubation, cells are protected from light by wrapping the plates in aluminum foil. Secondary antibody buffer is aspirated prior to a final 3 wash series with 100 µL/well incubation buffer. Cells are maintained in PBS (100 µL/well) for γH2AX foci detection.

The plate is then read on a SpectraMax i3 Multi-Mode Microplate Reader Platform with MiniMax 300 Imaging Cytometer (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA) using the included SoftMax Pro software (v6.3). The software is set to utilize the imaging read mode and end-point read type. (See Figures S1A–C for a detailed workflow for the SoftMax Pro software.) The proper fluorescence wavelengths are selected based on the specific secondary antibody used. Both plate type and sample wells utilized are selected to identify the wells to be imaged. Four imaging sites per well are utilized to ensure near-total well coverage during analysis. To optimize exposure duration, the Image Acquisition settings tab is used to select the wells containing the hypothesized minimum and maximum fluorescent signal and acquire images from both of these wells to adjust the fine focus and exposure of the instrument. This process can be repeated as needed to achieve image clarity. Under Image Analysis settings, a cell count analysis is selected, and the sample image is analyzed to confirm that the instrument is properly detecting individual cells. The object size parameters may be adjusted and the image reanalyzed as necessary to ensure distinct nuclei are properly identified. Using the average integrated intensity output parameter, the cell average γH2AX fluorescence is measured. This results in γH2AX fluorescence per cell, as these data are normalized by cell count. The selected wells from the plate are then read and the data exported for analysis. We have utilized 8 wells (of a 96-well plate) per condition, which results in the analysis of over 1.6 × 105 individual cells. Data analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, Inc., La Jolla, CA). The mean per well signal (relative fluorescence units) is graphed along with the 95% confidence interval (CI).

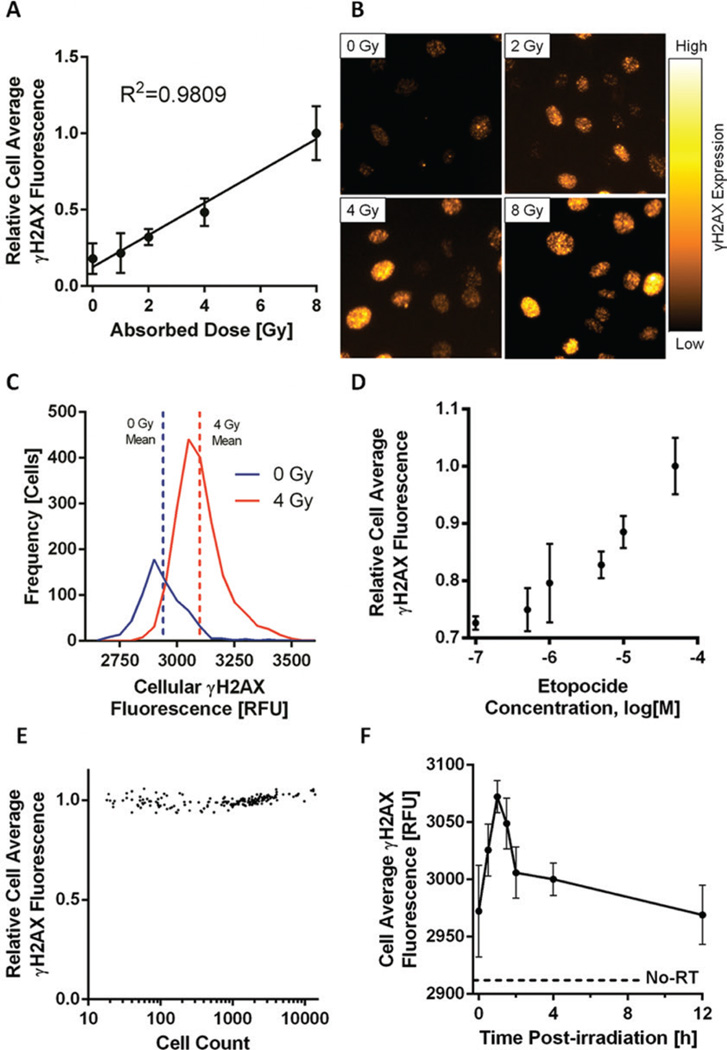

Using this method, a linear response of average per cell fluorescence with respect to dose is seen in HeLa cells over the range 0–8 Gy (Figure 1A) with representative microscopy images showing γH2AX foci at several dose points (Figure 1B) along with the number of cells at each relative fluorescence (Figure 1C). This approach is able to account for differences in the number of cells per well by providing a per cell intensity rather than a per well intensity. Our method is also amenable to identifying foci formed in response to chemotherapy-induced strand breaks. A dose-dependent response of γH2AX foci is seen over a range of etoposide (a known inducer of DNA strand breaks) doses as shown in Figure 1D. As shown in Figure 1E, plating a different number of cells per well results in stable values for the per cell γH2AX intensity across a wide range of cells plated (101–104 cells). The proposed method may also be employed to study detailed DNA repair kinetics following DNA DSB induction, as shown in Figure 1F. The entire procedure from start of the assay to data analysis takes approximately 3 h and provides a powerful platform for analysis of γH2AX foci in a high-throughput and reproducible manner.

Figure 1. Image cytometry assessment of DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) by γH2AX fluorescence.

The analysis of γH2AX using image cytometry provides a robust method for detection of DNA DSBs and DSB repair following both radiation and treatment with chemotherapeutic agents. (A) Relative cell average [+/− 95% confidence interval (CI)] γH2AX fluorescence of HeLa cells irradiated with increasing absorbed dose. (B) Representative microscopy images showing γH2AX foci at several dose points. Images were captured using an Olympus BX41 inverted microscope at 40× magnification. (C) The number of cells at each relative fluorescence level demonstrates increased γH2AX fluorescence immediately following a 4 Gy irradiation of HeLa cells (n = 8 wells for each dose point). (D) HeLa cells treated with various concentrations of etopocide to induce DNA DSBs. Cells showed excellent sensitivity over a range of drug concentrations. (E) Wells containing varied confluencies (101–104 cells) of HeLa cells irradiated uniformly to 2 Gy showing γH2AX fluorescence is independent of cell number assayed. (F) To investigate DNA DSB repair kinetics following a 4 Gy irradiation, HeLa cells were fixed at various time points and showed an immediate sharp increase in mean cell average γH2AX fluorescence as a response to DNA DSB induction with a gradual decrease correlating with DNA DSB resolution. Mean cell average γH2AX fluorescence of un-irradiated (No-RT) HeLa cells is shown as a dashed line.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the NIH/NCI P30 CA014520-UW Comprehensive Cancer Center Grant and CA160639 (R.J.K.). T.L.F. was supported in part by the University of Wisconsin Science and Medicine Graduate Research Scholars program. This paper is subject to the NIH Public Access Policy.

Footnotes

Supplementary material for this article is available at www.BioTechniques.com/article/114248.

Author contributions

T.L.F. contributed to the conception, development, execution, analysis, writing and editing of manuscript. A.M.B. contributed to the execution and analysis of experiments. B.P.B. contributed to the writing and editing of the manuscript. R.J.K. contributed to the analysis, writing, and editing of manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Rothkamm K, Horn S. Gamma-H2AX as protein biomarker for radiation exposure. Ann. Ist. Super. Sanita. 2009;45:265–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuo L, Yang LX. Gamma-H2AX - a novel biomarker for DNA double-strand breaks. In Vivo. 2008;22:305–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sharma A, Singh K, Almasan A. Histone H2AX phosphorylation: a marker for DNA damage. Methods Mol. Biol. 2012;920:613–626. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-998-3_40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scully R, Xie A. Double strand break repair functions of histone H2AX. Mutat. Res. 2013;750:5–14. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2013.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schuler N, Palm J, Kaiser M, Betten D, Furtwangler R, Rübe C, Graf N, Rübe CE. DNA-damage foci to detect and characterize DNA repair alterations in children treated for pediatric malignancies. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e91319. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fowler TL, Fulkerson RK, Micka JA, Kimple RJ, Bednarz BP. A novel high-throughput irradiator for in vitro radiation sensitivity bioassays. Phys. Med. Biol. 2014;59:1459–1470. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/59/6/1459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.