Abstract

Background

Participation in drinking games is associated with excessive drinking and alcohol risks. Despite the growing literature documenting the ubiquity and consequences of drinking games, limited research has examined the influence of psychosocial factors on the experience of negative consequences as the result of drinking game participation.

Objectives

The current event-level study examined the relationships among drinking game participation, social anxiety, drinking refusal self-efficacy (DRSE) and alcohol-related consequences in a sample of college students.

Methods

Participants (n =976) reported on their most recent drinking occasion in the past month in which they did not preparty.

Results

After controlling for sex, age, and typical drinking, higher levels of social anxiety, lower levels of DRSE, and playing drinking games predicted greater alcohol-related consequences. Moreover, two-way interactions (Social Anxiety × Drinking Games, DRSE × Drinking Games) demonstrated that social anxiety and DRSE each moderated the relationship between drinking game participation and alcohol-related consequences. Participation in drinking games resulted in more alcohol problems for students with high social anxiety, but not low social anxiety. Students with low DRSE experienced high levels of consequences regardless of whether they participated in drinking games; however, drinking game participation was associated with more consequences for students confident in their ability to resist drinking.

Conclusion

Findings highlight the important role that social anxiety and DRSE play in drinking game-related risk, and hence provide valuable implications for screening at-risk students and designing targeted harm reduction interventions that address social anxiety and drink refusal in the context of drinking games.

Keywords: College alcohol use, drinking games, self-efficacy, social anxiety

Introduction

Drinking games are a common part of the college drinking culture (1–7). According to Zamboanga and colleagues (8), drinking games are: (i) governed by rules that dictate when and how much alcohol players consume, (ii) designed to facilitate rapid and excessive alcohol consumption, (iii) social in nature, and (iv) involve physical or cognitive tasks. There are several categories of drinking games, including games that involve performing a skill (e.g. flip pong, beer hockey), communal drinking that encourages group cohesion (e.g. everyone drinking to key words in a movie or TV show), or competition between individuals or teams (e.g. beer pong) (8,9).

Given the fast-paced consumption and intoxication involved in playing drinking games, it is not surprising that game players tend to drink more than they would consume on a typical drinking occasion (10–12) and face heightened risk for a range of alcohol-related negative consequences (e.g. passing out, academic problems, aggression, and physical injuries) (1,9,10,12). Indeed, avoiding drinking games appears to be a useful protective strategy associated with less alcohol consumption and fewer alcohol-related consequences (13). The social context of drinking games, where students are exposed to peer pressure to consume large quantities of alcohol, may contribute to the higher levels of alcohol problems (12,14). For example, during drinking games students may be encouraged or pressured to drink more than intended by peers, and when students fail to follow rules or try to avoid drinking they may be ridiculed (3). The social nature of drinking games may result in individuals who are uncomfortable in social settings or lack the skills needed to refuse drinks being particularly vulnerable to the negative consequences of drinking games. The current study sought to extend past research by examining whether social anxiety and drinking refusal self-efficacy (DRSE) moderate the association between drinking game participation and event-level alcohol consequences.

Drinking games and social anxiety

Given the social context of drinking games, social anxiety may be an important predictor of alcohol-related consequences resulting from drinking game participation. Individuals with elevated levels of social anxiety tend to feel particularly uncomfortable socializing and meeting new people, and are fearful of being negatively evaluated by peers. A recent meta-analysis of 44 college-based studies found that social anxiety was negatively correlated with alcohol use, but positively correlated with alcohol-related problems (15). On one hand, students with elevated levels of social anxiety may intentionally avoid drinking excessively to minimize the likelihood of attention or embarrassment. On the other hand, participating in drinking games appears to reduce tension and facilitate social interaction for socially anxious students by reducing shyness and inhibitions (16–18). Drinking games establish clear rules for drinking and interacting with peers and can therefore provide a structured environment for socially anxious individuals to become more involved in their social group. Although many students with heightened social anxiety may avoid social drinking entirely, those who do participate in college social contexts may be inclined to cope with anxiety by using alcohol and other means of alleviating tension, such as drinking games (19–21). The current study included only those students reporting past month prepartying (i.e. pregaming) – defined as “the consumption of alcohol prior to attending a planned event or activity (e.g. party, bar, concert, sporting event) at which more alcohol may or may not be consumed (22, p. 238)” – and heavy drinking in order to examine the relevant contextual relationships among social anxiety levels, drinking game participation, and alcohol risk.

Although there is evidence that those with elevated levels of social anxiety tend to shy away from playing drinking games (10,16,23), other researchers have suggested that there may be a positive relationship between social anxiety and drinking game participation (17,18). Nonetheless, research supports that social anxiety influences the decision to play drinking games. What is less clear however is how participation in drinking games interacts with social anxiety to predict alcohol-related consequences. Because individuals with elevated levels of social anxiety may drink in order to loosen up and be more sociable (24), when they do play drinking games they may be at greater risk for excessive drinking and alcohol-related problems than non-socially anxious peers. More research is needed to help determine whether social anxiety is a risk factor for alcohol consequences experienced during and after playing drinking games.

Drinking refusal and self-efficacy

Students’ perceptions of their ability to refuse an alcoholic drink (i.e. drinking refusal self-efficacy [DRSE]) (25,26) may also be an important moderator of drinking game participation on alcohol consequences. Individuals who believe they lack the ability to resist alcohol tend to have less control when drinking, report greater alcohol consumption, and experience more alcohol-related consequences (27–30). Self-efficacy is often context-specific, and students may find it particularly challenging to refuse drinks within some social settings (31,32). Given the structure of drinking games and the prescribed rules for when and how much to drink, it may be particularly difficult for students with low DRSE to stop and refuse drinks even when they know they have reached their limit. Indeed, students who choose to participate in drinking games in order to fit in with their peers may lack assertiveness and the social skills needed to resist group pressure to drink (17). To date, no studies have examined whether drinking games are particularly risky for students who lack confidence in their ability to resist drinks.

Current study

The majority of studies examining the association between drinking game participation and alcohol consequences have relied on global measures of drinking outcomes (3,4,33–36). Global measures do not specifically examine alcohol problems that occur during or after playing drinking games, and while these measures are useful for determining whether drinking game participation is associated with more consequences in general, they do not demonstrate whether playing games increases consequences during a specific drinking event. The current study seeks to add to the limited event-level drinking games research (e.g. 2,37,38,39) by examining social anxiety, DRSE, drinking game participation, and alcohol consequences among college students reporting heavy drinking and prepartying within the past month. Specifically, we assessed whether social anxiety or DRSE moderated the association between drinking game participation and alcohol consequences during a particular drinking event. We predicted that there would be a stronger positive association between drinking game participation and negative consequences among students who reported higher levels of social anxiety or lower levels of DRSE.

Methods

Participants and procedure

Participants in the current study were a subset of students from two different universities on the West Coast of the US taking part in a larger alcohol intervention study. A random sample of 6,000 undergraduate students from a large public university and a mid-sized private university were invited via mail and email to participate in a study examining college alcohol use. The Institutional Review Boards at the participating universities approved all study procedures. Of the participants invited, 2,689 (44.8%) provided informed consent and completed an initial screening survey. Men who reported drinking five or more drinks on one occasion and women who reported drinking four or more drinks on one occasion in the past month (n =1,493; 55.5%) were asked to complete an additional baseline survey. Of these 1493 students, 1,367 (91.6%) completed the baseline survey and received a nominal cash incentive for their time.

As part of the baseline survey, participants reported whether they had prepartied (i.e. consumed “alcohol prior to attending an event or activity [e.g. party, bar, concert] at which more alcohol may or may not be consumed”) at least once in the past month. Participants who had prepartied (n =988) were asked a series of event-level questions about drinking game participation and alcohol-related consequences on both the last drinking event when they had prepartied and when they had not prepartied. As prepartying and drinking game participation can potentially have an additive influence on consequences (38), the current study focuses on the event in which students had not prepartied. Thus, our analyses looked solely at the context of drinking games and its influence on consequences moderated by social anxiety and DRSE in heavy drinking college students. Only students who responded to the question assessing drinking game participation during a drinking event in which they had not prepartied were included in the current analyses (n =976). Overall, 45.3% (n =442) reported that they had played drinking games during the last occasion that they drank and did not preparty. The final sample was 63.6% female and ranged in age from 18–24 years (M =20.11, SD =1.35). The racial composition of the sample was 67.7% White, 12.6% Asian, 11.8% Multiracial, 3.2% Other, 2.4% African American, 1.9% Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, and 0.4% American Indian/Alaskan Native. With regard to ethnicity, 12.2% of participants identified as Hispanic/Latino (a). The sample demographics were similar to the larger sample from which it was drawn (62% female, 68% White, mean age =20.1 years). Data used in the current analyses were collected prior to participants receiving any alcohol intervention.

Measures

Prior to answering questions regarding alcohol use participants were presented with the definition of a standard drink (i.e. 12 oz. beer, 10 oz. wine cooler, 4 oz. wine, 1 oz. 100 proof [1 ¼ oz. 80 proof] liquor).

Drinking game participation

Participants were asked whether or not they had played drinking games (Yes =1, No =0) during the last occasion when they drank but did not preparty.

Social anxiety

Social anxiety was assessed using the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (SIAS, 40). Due to a computer programming error, a single item from the 20-item measure was not assessed and a composite was created from the remaining 19 items (α =0.93). The SIAS assesses anxiety related to social interactions (i.e. “distress when initiating and maintaining conversations with friends, strangers, or potential mates”) (41). Example items include, “I have difficulty talking with other people” and “When mixing socially, I am uncomfortable”. Responses were measured on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (Not at all) to 4 (Extremely). A mean composite was created with higher scores indicating greater social anxiety. The SIAS has demonstrated good discriminant and construct validity, internal consistency, and test-retest reliability (41,42).

Drinking refusal self-efficacy

A revised adolescent version of the Drinking Refusal Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (DRSEQ; 27) was used to assess self-efficacy beliefs. Students were asked about their ability to refuse drinks in 19 different drinking situations (α =0.94) including, “When someone offers me a drink” and “When I am angry.” Responses were given on a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (I am very sure I could NOT resist drinking) to 6 (I am very sure I could resist drinking). Participants’ responses were summed with higher scores indicating that students were more confident in their ability to resist drinking. The revised adolescent version of the DRSEQ has been shown to be reliable and valid (43).

Drinking behavior

Alcohol use was measured using the Daily Drinking Questionnaire (44). The DDQ assesses typical weekly drinking behaviors during the past month. Participants reported the typical number of drinks consumed each day of the week and responses were summed to create a measure of weekly alcohol consumption. The DDQ has demonstrated good validity (44) and test-retest reliability (45).

Event-level consequences

Negative alcohol-related consequences were measured using a modified version of the original Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire (BYAACQ; 46). Seven of the original 24 items were not relevant to event-level assessment (e.g. “I often have ended up drinking on nights when I planned not to drink), and, thus, were not included in the survey (see 38 for more details). Participants indicated whether they had experienced (Yes =1, No =0) 17 alcohol-related consequences (α=0.87) during the last occasion when they drank but did not preparty. The measure included items such as “I found it difficult to limit how much I drank” and “I did impulsive things I regretted later.” Responses were summed to create a measure of total number of consequences experienced during the event. The BYAACQ has demonstrated good validity and reliability (47).

Analytic plan

A three-step hierarchical multiple regression analysis examined whether DRSE and social anxiety moderated the relationship between drinking game participation and alcohol consequences. At Step 1, student sex (male =0, female =1), age, and typical weekly drinking were entered into the model. The main effects of social anxiety, DRSE and playing drinking games were entered in Step 2, and the interaction terms involving these variables in Step 3. Predictors were standardized prior to calculation of interaction terms to minimize problems of multicollinearity.

Results

Participants reported drinking an average of 5.2 drinks over a period of 3.2 hours during the event they were asked to recall. The number of alcohol consequences students experienced was positively correlated with typical weekly drinking, r(974) =0.21, p<0.001, social anxiety, r(974) =0.15, p<0.001, and negatively related to DRSE, r(974) = −0.37, p<0.001 (see Table 1). As previously reported in Hummer et al. (38), students who reported playing drinking games experienced significantly more consequences (M =3.37, SD =3.42) than students who did not play drinking games (M =2.66, SD =3.0), t(974) =3.47, p =0.001. Students who participated in drinking games (M =26.4, SD =14.0) did not significantly differ from students who did not play drinking games (M =25.1, SD =13.8) in their self-reports of social anxiety, t(974) =1.46, p =0.15. Those who played drinking games did, however, report lower DRSE (M =94.5, SD =16.4) than students who did not play drinking games (M =96.8, SD =13.6), t(974) =2.43, p =0.015.

Table 1.

Summary of means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations for measures of social anxiety, DRSE, weekly drinking, and alcohol consequences.

| Variable | M | SD | Range | V1 | V2 | V3 | V4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| V1 | Social anxiety | 25.73 | 13.88 | 0–69 | – | |||

| V2 | DRSE | 95.78 | 14.95 | 20–114 | −0.18*** | – | ||

| V3 | Typical weekly drinking | 11.65 | 8.90 | 0–44 | −0.08** | − 0.23*** | – | |

| V4 | Alcohol consequences | 2.98 | 3.22 | 0–17 | 0.15*** | − 0.37*** | 0.21*** | – |

DRSE, Drinking refusal self-efficacy.

p<0.05.

p<0.01.

p<0.001.

Hierarchical multiple regression analyses

The results of the hierarchical multiple regression model are presented in Table 2. At Step 1, student sex (β =0.08, p =0.014) and typical weekly drinking (β =0.23, p<0.001) uniquely contributed to the prediction of event-level alcohol consequences. Female students and those who reported greater typical weekly drinking experienced more event-level alcohol consequences. At Step 2, higher levels of social anxiety (β =0.10, p =0.001) and playing drinking games (β =0.07, p =0.017) were associated with greater consequences. Higher levels of DRSE were related to fewer consequences (β =−0.32, p<0.001). At Step 3, Social Anxiety × Drinking Games (β =0.06, p =0.031) and DRSE × Drinking Games (β =0.07, p =0.026) interactions significantly contributed to the model1. Although the incremental change in R2 for the final step of the regression was small, the size is consistent with those observed in social science research (48). The interactions were graphed at one standard deviation below the mean (low DRSE or low social anxiety) and above the mean (high DRSE or high social anxiety) (49).

Table 2.

Hierarchical multiple regression analyses predicting event-level alcohol consequences from drinking games, DRSE, and social anxiety.

| Step | Variable entered | Step 1 β | Step 2 β | Step 3 β | SE | R2 | Model F | Δ F |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | Sex | 0.08* | 0.10** | 0.10** | 0.10 | |||

| Age | −0.02 | −0.01 | −0.02 | 0.10 | ||||

| Typical weekly drinking | 0.23*** | 0.16*** | 0.16*** | 0.10 | 0.05 | 16.96*** | ||

| 2. | Drinking games | 0.07* | 0.07* | 0.10 | ||||

| Social anxiety | 0.10*** | 0.10*** | 0.10 | |||||

| DRSE | −0.32*** | −0.33*** | 0.10 | 0.17 | 34.48*** | 49.46*** | ||

| 3. | Social Anxiety × Drinking Games | 0.06* | 0.10 | |||||

| DRSE × Drinking Games | 0.07* | 0.10 | 0.18 | 27.05*** | 4.10* |

Standard errors are reported for the final step of the regression. DRSE, Drinking refusal self-efficacy.

p<0.05.

p<0.01.

p<0.001.

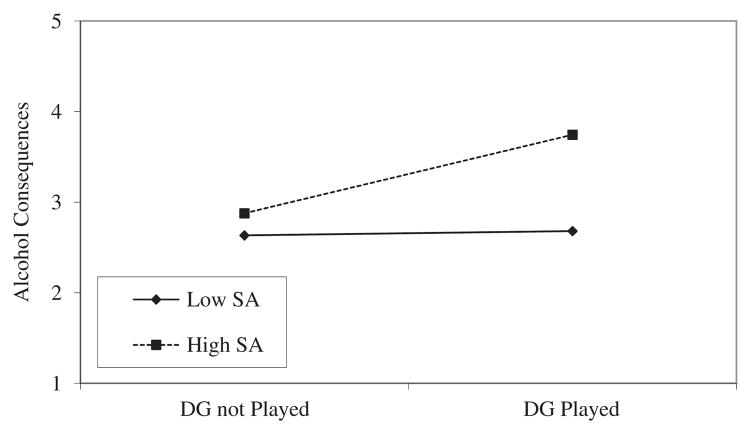

Simple slope analyses for the social anxiety interaction were non-significant for students low in social anxiety (β =0.02, p =0.86), but were significant for students with high social anxiety (β =0.43, p =0.001; Figure 1). Playing drinking games was associated with greater event-level consequences for students reporting high (but not low) social anxiety.

Figure 1.

Effect of drinking game participation on alcohol consequences moderated by social anxiety. DG, Drinking games; SA, Social anxiety.

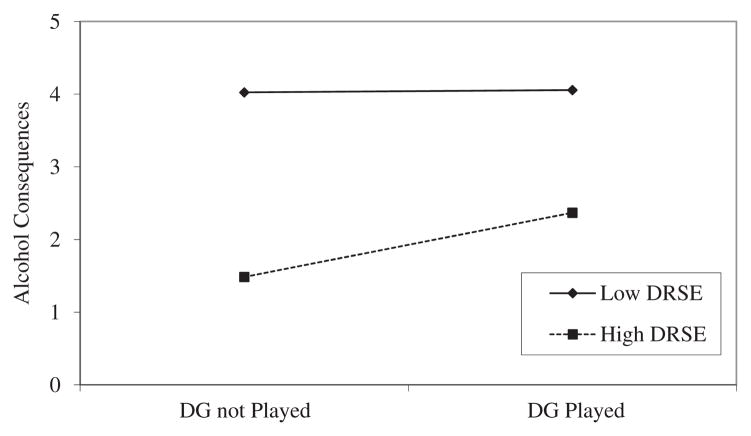

Simple slopes for the DRSE interaction were significant for high DRSE (β =0.44, p =0.001), but not low DRSE (β = 0.02, p =0.91; Figure 2). Students who lack confidence in their ability to refuse drinks are likely to experience more consequences regardless of whether they participate in drinking games. In contrast, among participants reporting high DRSE, participating in drinking games (vs. non-participation) is associated with greater alcohol consequences.

Figure 2.

Effect of drinking game participation on alcohol consequences moderated by drinking refusal self-efficacy. DG, Drinking games; DRSE, Drinking refusal self-efficacy.

Discussion

In the current study, we explored how social anxiety and DRSE uniquely influenced the relationship between drinking game participation and alcohol-related consequences in a large sample of heavy drinking college students. Findings show that drinking games were associated with event-level consequences for students who reported higher levels of social anxiety, but not for students low in social anxiety. Although it is plausible that drinking games may serve to reduce tension and inhibitions and make socializing less intimidating for socially anxious students, the current findings show that students with elevated social anxiety experience greater problems as a result of their participation. Anxious or distressed students may lack the attention, decision-making, competency (for review see 50), supportive peers (51,52), and drinking control strategies (e.g. 53) known to protect students from alcohol-related harm. Particularly in the high-risk context of drinking games, lacking protective resources may further heighten risks for negative outcomes. Further, in contrast to studies showing that students with high social anxiety generally avoid participating in drinking games (10,16,23), social anxiety was not associated with game playing in this study. Students in the current sample may represent a subset of students high in social anxiety who also actively engage in the college drinking culture.

These results provide important implications for college counseling centers that commonly treat students seeking help for social anxiety. Screening presenting students for heavy drinking and drinking game participation may help target a high-risk subgroup of students that could benefit from brief alcohol interventions. Integrated skills training interventions could address strategies for coping with social anxiety symptoms as well as ways in which students could feel more comfortable and protect themselves in specific drinking settings.

Findings also shed light on the risks associated with drinking games for those students vulnerable to social pressure to engage in excessive alcohol use in this common drinking context. Despite the majority of participants reporting that they were confident in their abilities to refuse drinks, self-efficacy was found to moderate the relationship between drinking games and alcohol-related consequences. Contrary to hypotheses, after controlling for demographics, past drinking and social anxiety, drinking game participation was not associated with greater event-level consequences for students who lacked confidence in their ability to refuse drinks. The lack of association between drinking game participation and consequences for students low in DRSE may reflect a ceiling effect in which these students experienced more alcohol consequences regardless of whether they participated in drinking games. In contrast, drinking game participation was associated with more event-level consequences for students who believed they were capable of resisting drinks. Drinking games, which are bound by strict rules that dictate when and how much players must drink, may hamper students’ general ability to refuse drinks, even when they think they have the capacity to do so.

Brief motivational interventions (BMIs) (54) often include harm reduction strategies associated with refusing drinks. Integrating discussions of drink refusal as it relates to these high-risk drinking contexts may increase students’ confidence and skills in refusing drinks during drinking games. Overall however, participants low in DRSE experienced nearly double the consequences of participants high in DRSE. These students may be at substantial risk for alcohol-related problems and trajectories of alcohol dependence, and hence may benefit from interventions that bolster self-efficacy and build skills for refusing drinks, regardless of whether drinking games are played or not. Many protective behavioral strategies (PBS) (55) are linked to drinking refusal skills, such as avoiding shots of liquor or determining not to exceed a set number of drinks. PBS skills training intervention components, which are shown to independently predict lower levels of alcohol consumption (56,57), may be particularly helpful for at-risk students reporting low DRSE.

The current study is limited in a number of ways. The present sample included only heavy drinkers who reported prepartying in the past month, which may not be representative of all college students. Future studies should examine how social anxiety as well as DRSE impact drinking game-related risks among a general sample of college students. Further, this study provides insight into the effects of drinking games when they are played during a drinking event that does not include prepartying. Prepartying and playing drinking games are distinct high-risk activities; however, drinking games are often played for the purpose of prepartying (38,58). More research is needed to assess the moderating effects of social anxiety and DRSE when drinking games are played during prepartying, including the comparison of the effects when students play with strangers, acquaintances or close friends. Moreover, this study did not assess the type of game in which a student engaged during the drinking event described. There are hundreds of different types of drinking games (8,9), and it may be that social anxiety and DRSE have differential moderating effects for games designed to create competition between teams or communal games where all players are expected to drink at the same time (e.g. media games). Further event-level analysis is needed to explicate the relationships among DRSE, social anxiety, and game type. Along these lines, although we did not find that social anxiety and DRSE had interactive effects on drinking games-related risks in the current study, further explication may be warranted. For example, recent research did find that among those high in social anxiety and low in DRSE, high (as opposed to low) tension reduction alcohol expectancies substantially increased alcohol-related problems (59). Finally, the current study utilized cross-sectional data; longitudinal research is needed to examine whether social anxiety and DRSE predict alcohol consequences during future episodes of drinking game participation.

The current study examined the relationships among drinking game participation, social interaction anxiety, DRSE and alcohol-related negative consequences in a sample of heavy-drinking college students. An important strength of the current study is its event-level design, which enabled us to demonstrate the unique influences of social anxiety and DRSE in predicting drinking game-related risks during a specific drinking event. Results point to new ways to make interventions more effective, including targeted harm reduction interventions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Daniel Smith for his help with the literature review and an early draft of the introduction.

Footnotes

Adding a Social Anxiety × DRSE × Drinking Games term at a fourth step did not add to the variance explained and the three-way interaction did not approach significance, β = −0.03, p =0.28.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this paper.

References

- 1.Borsari B. Drinking games in the college environment: a review. J Alcohol Drug Educat. 2004;48:29–51. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borsari B, Boyle KE, Hustad JTP, Barnett NP, Tevyaw TO, Kahler CW. Drinking before drinking: pregaming and drinking games in mandated students. Addictive Behav. 2007;32:2694–2705. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cameron JM, Heidelberg N, Simmons L, Lyle SB, Mitra-Varma K, Correia C. Drinking game participation among undergraduate students attending national alcohol screening day. J Am College Health. 2010;58:499–506. doi: 10.1080/07448481003599096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cameron JM, Leon MR, Correia CJ. Extension of the simulated drinking game procedure to multiple drinking games. Experim Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;19:295–302. doi: 10.1037/a0024312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kenney SR, Hummer JF, LaBrie JW. An examination of prepartying and drinking game playing during high school and their impact on alcohol-related risk upon entrance into college. J Youth Adolesc. 2010;39:999–1011. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9473-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson TJ, Cropsey KL. Sensation seeking and drinking game participation in heavy drinking college students. Addictive Behav. 2000;25:109–116. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00118-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adams CE, Nagoshi CT. Changes over one semester in drinking game playing and alcohol use and problems in a college student sample. Subst Abuse. 1999;20:97–106. doi: 10.1080/08897079909511398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zamboanga BL, Pearce MW, Kenney SR, Ham LS, Woods OE, Borsari B. Are “extreme consumption games” drinking games? Sometimes it’s a matter of perspective. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2013;39:275–279. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2013.827202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.LaBrie JW, Ehret PJ, Hummer JF. Are they all the same? An exploratory, categorical analysis of drinking game types. Addictive Behav. 2013;38:2133–2139. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson TJ, Wendel J, Hamilton S. Social anxiety, alcohol expectancies, and drinking-game participation. Addictive Behav. 1998;23:65–79. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(97)00033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Newman IM, Crawford JK, Nellis MJ. The role and function of drinking games in the university community. J Am College Health. 1991;39:171–175. doi: 10.1080/07448481.1991.9936230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Polizzotto MN, Saw MM, Tjhung I, Chua EH, Stockwell TR. Fluid skills: drinking games and alcohol consumption among Australian university students. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2007;26:469–475. doi: 10.1080/09595230701494374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frank C, Thake J, Davis CG. Assessing the protective value of protective behavioral strategies. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2012;73:839–843. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Borsari B, Carey KB. Peer influences on college drinking: a review of the research. J Subst Abuse. 2001;13:391–424. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(01)00098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schry AR, White SW. Understanding the relationship between social anxiety and alcohol use in college students: a meta-analysis. Addictive Behav. 2013;38:2690–2706. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ham LS, Zamboanga BL, Olthuis JV, Casner HG, Bui N. No fear, just relax and play: social anxiety, alcohol expectancies, and drinking games among college students. J Am College Health. 2010;58:473–479. doi: 10.1080/07448480903540531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson TJ, Hamilton S, Sheets VL. College students’ self-reported reasons for playing drinking games. Addictive Behav. 1999;24:279–286. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(98)00047-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pedersen W. Drinking games adolescents play. Br J Addictions. 1990;85:1483–1490. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1990.tb01632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Norberg MM, Norton AR, Olivier J. Refining measurement in the study of social anxiety and student drinking: who you are and why you drink determines your outcomes. Psychol Addictive Behav. 2009;23:586–597. doi: 10.1037/a0016994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stewart SH, Morris E, Mellings T, Komar J. Relations of social anxiety variables to drinking motives, drinking quantity and frequency, and alcohol-related problems in undergraduates. J Mental Health. 2006;15:671–682. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thompson RD, Goldsmith AA, Tran GQ. Alcohol and drug use in socially anxious adults. In: Alfano CA, Beidel DC, editors. Social anxiety disorder in adolescents and young adults: translating developmental science into practice. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association Books; 2011. pp. 107–123. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pedersen ER, LaBrie JW. Partying before the party: examining prepartying behavior among college students. J Am College Health. 2007;56:237–245. doi: 10.3200/JACH.56.3.237-246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ham LS, Hope DA. Incorporating social anxiety into a model of college problem drinking: replication and extension. Psychol Addictive Behav. 2006;20:348–355. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.3.348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Norberg MM, Olivier J, Alperstein DM, Zvolensky MJ, Norton AR. Adverse consequences of student drinking: the role of sex, social anxiety, drinking motives. Addictive Behav. 2011;36:821–828. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oei TP, Burrow T. Alcohol expectancy and drinking refusal self-efficacy: a test of specificity theory. Addictive Behav. 2000;25:499–507. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(99)00044-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Young R, Oei TP, Crook GM. Development of a drinking self-efficacy questionnaire. J Psychopathol Behavioral Assess. 1991;13:822–830. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baldwin AR, Oei TPS, Young R. To drink or not to drink: the differential role of alcohol expectancies and drinking refusal self-efficacy in quantity and frequency of alcohol consumption. Cognitive Ther Res. 1993;17:511–530. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Oei TP, Hasking P, Phillips L. A comparison of general self-efficacy and drinking refusal self-efficacy in predicting drinking behavior. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2007;33:833–841. doi: 10.1080/00952990701653818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Young R, Connor JP, Ricciardelli LA, Saunders JB. The role of alcohol expectancy and drinking refusal self-efficacy beliefs in university student drinking. Alcohol Alcoholism. 2005;41:70–75. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agh237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ehret PJ, Ghaidarov TM, LaBrie JW. Can you say no? Examining the relationship between drinking refusal self-efficacy and protective behavioral strategy use on alcohol outcomes. Addictive Behav. 2013;38:1898–1904. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ralston TE, Palfai TP. Effects of depressed mood on drinking refusal self-efficacy: examining the specificity of drinking contexts. Cognit Behav Ther. 2010;39:262–269. doi: 10.1080/16506073.2010.501809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Oei TP, Morawska A. A cognitive model of binge drinking: the influence of alcohol expectancies and drinking refusal self-efficacy. Addictive Behav. 2004;29:159–179. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(03)00076-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zamboanga BL, Leitkowski LK, Rodriguez L, Cascio KA. Drinking games in female college students: more than just a game? Addictive Behav. 2006;31:1485–1489. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zamboanga BL, Schwartz SJ, Van Tyne K, Ham LS, Olthuis JV, Huang S, Kim SY, et al. Drinking game behaviors among college students: how often and how much? Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2010;36:175–179. doi: 10.3109/00952991003793869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grossbard J, Geisner IM, Neighbors C, Kilmer JR, Larimer M. Are drinking games sports? College athlete participation in drinking games and alcohol-related problems. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2007;68:97–105. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alfonso J, Deschenes SD. Do drinking games matter? An examination by game type and gender in a mandated student sample. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2013;39:312–319. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2013.770519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Clapp JD, Lange JE, Min JW, Shillington A, Johnson M, Voas RB. Two studies examining environmental predictors of heavy drinking by college students. Prevention Sci. 2003;4:99–108. doi: 10.1023/a:1022974215675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hummer J, Napper LE, Ehret PE, LaBrie JW. Event-specific risk and ecological factors associated with prepartying among heavier drinking college students. Addictive Behav. 2013;38:1620–1628. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pedersen ER, LaBrie JW. Drinking game participation among college students: gender and ethnic implications. Addictive Behav. 2006;31:2105–2115. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mattick RP, Clarke JC. Development and validation of measures of social phobia scrutiny fear and social interaction anxiety. Behav Res Ther. 1998;36:455–470. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)10031-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brown EJ, Turovsky J, Heimberg RG, Juster HR, Brown TA, Barlow DH. Validation of the social interaction anxiety scale and the social phobia scale across the anxiety disorders. Psycholog Assess. 1997;9:21–27. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Safren SA, Turk CL, Heimberg RG. Factor structure of the social interaction anxiety scale and the social phobia scale. Behav Res Ther. 1998;36:443–453. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(98)00032-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Young RM, Hasking PA, Oei TPS, Loveday W. Validation of the Drinking Refusal Self-Efficacy Questionnaire – revised in an adolescent sample (DRSEQ-RA) Addictive Behav. 2007;32:862–868. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: the effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1985;53:189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Neighbors C, Dillard AJ, Lewis MA, Bergstrom RL, Neil TA. Normative misperceptions and temporal precedence of perceived norms and drinking. J Stud Alcohol. 2006;67:290–299. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kahler CW, Strong DR, Read JP. Toward efficient and comprehensive measurement of the alcohol problems continuum in college students: The Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:1180–1189. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000171940.95813.a5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kahler CW, Hustad J, Barnett NP, Strong DR, Borsari B. Validation of the 30-day version of the Brief Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire for use in longitudinal studies. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2008;69:611–615. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 3. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Castaneda AE, Tuulio-Henriksson A, Marttunen M, Suvisaari J, Lönnqvist J. A review on cognitive impairments in depressive and anxiety disorders with a focus on young adults. J Affect Disord. 2008;106:1–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.La Greca AM, Lopez N. Social anxiety among adolescents: linkages with peer relations and friendships. J Abnormal Child Psychol. 1998;26:83–94. doi: 10.1023/a:1022684520514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Buckner JD, Schmidt NB, Lang AR, Small JW, Schlauch RC, Lewinsohn PM. Specificity of social anxiety disorder as a risk factor for alcohol and cannabis dependence. J Psychiat Res. 2008;42:230–239. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kenney SR, LaBrie JW. Use of protective behavioral strategies and reduced alcohol risk: examining the moderating effects of mental health, gender, and race. Psychol Addictive Behav. 2013;27:997–1009. doi: 10.1037/a0033262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cronce JM, Larimer M. Individual-focused approaches to the prevention of college student drinking. Alcohol Res Health. 2011;34:210–221. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Martens MP, Ferrier AG, Sheehy MJ, Korbett K, Anderson DA, Simmons A. Development of the Protective Behavioral Strategies Survey. J Stud Alcohol. 2005;66:698–705. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Barnett NP, Murphy JG, Colby SM, Monti PM. Efficacy of counselor vs. computer-delivered intervention with mandated college students. Addictive Behav. 2007;32:2529–2548. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Larimer ME, Lee CM, Kilmer JR, Fabiano PM, Stark CB, Geisner IM, Mallett KA, et al. Personalized mailed feedback for college drinking prevention: a randomized clinical trial. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2007;75:285–293. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.2.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.DeJong W, DeRicco B, Schneider SK. Pregaming: an exploratory study of strategic drinking by college students in Pennsylvania. J Am College Health. 2010;58:307–316. doi: 10.1080/07448480903380300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Goldsmith AA, Thompson RD, Black JJ, Tran GQ, Smith JP. Drinking refusal self-efficacy and tension-reduction alcohol expectancies moderating the relationship between generalized anxiety and drinking behaviors in young adult drinkers. Psychol Addictive Behav. 2012;26:59–67. doi: 10.1037/a0024766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]