Abstract

Background

Hypoderaeum conoideum is a neglected but important trematode. The life cycle of this parasite is complex: snails serve as the first intermediate hosts: bivalves, fishes or tadpoles serve as the second intermediate hosts, and poultry (such as chickens and ducks) act as definitive hosts. In recent years, H. conoideum has caused significant economic losses to the poultry industry in some Asian countries. Despite its importance, little is known about the molecular ecology and population genetics of this parasite. Knowledge of mitochondrial (mt) genome of H. conoideum can provide a foundation for phylogenetic studies as well as epidemiological investigations.

Methods

The entire mt genome of H. conoideum was amplified in five overlapping fragments by PCR and sequenced, annotated and compared with mt genomes of selected trematodes. A phylogenetic analysis of concatenated mt amino acid sequence data for H. conoideum, eight other digeneans (Clonorchis sinensis, Fasciola gigantica, F. hepatica, Opisthorchis felineus, Schistosoma haematobium, S. japonicum, S. mekongi and S. spindale) and one tapeworm (Taenia solium; outgroup) was conducted to assess their relationships.

Results

The complete mt genome of H. conoideum is 14,180 bp in length, and contains 12 protein-coding genes, 22 transfer RNA genes, two ribosomal RNA genes and one non-coding region (NCR). The gene arrangement is the same as in Fasciola spp, with all genes being transcribed in the same direction. The phylogenetic analysis showed that H. conoideum had a relatively close relationship with F. hepatica and other members of the Fasciolidae, followed by the Opisthorchiidae, and then the Schistosomatidae.

Conclusions

The mt genome of H. conoideum should be useful as a resource for comparative mt genomic studies of trematodes and for DNA markers for systematic, population genetic and epidemiological studies of H. conoideum and congeners.

Keywords: Hypoderaeum conoideum, Mitochondrial genome

Background

Echinostomatid trematodes comprise a group of at least 60 species [1], some of which are of socioeconomic significance in animals. Hypoderaeum conoideum (Bloch, 1782) is an important member of the family. This echinostomatid was originally found in the intestines of birds and is known to infect chickens, ducks and geese in many countries around the world [2-4]. It has also been found to infect humans and cause echinostomiasis in Thailand [5,6]. Freshwater snails, Planorbis corneus, Indoplanorbis exustus, Lymnaea stagnalis, L. limosa, L. ovata and L. rubiginosa, act as first intermediate hosts and shed the cercariae; bivalves, fishes or tadpoles can act as second intermediate hosts [3,5].

The accurate identification of species and genetic variants of Hypoderaeum conoideum will be central to investigating its biology, epidemiology and ecology, and also has implications for the diagnosis of infections. Although morphological features are used to identify this and other trematodes, such characters are not always reliable [7]. Due to these constraints, various molecular methods have been established for specific identification [7]. For instance, PCR-based techniques using genetic markers in nuclear ribosomal (r) and mitochondrial (mt) DNA have been widely used [7]. The sequences of the first and second internal transcribed spacers (ITS-1 and ITS-2 = ITS) of nuclear rDNA have been particularly useful for specific identification, based on consistent levels of sequence difference between species and little variation within individual species [7], while the mitochondrial gene cox1 has been used for studying genetic variation and relationships among different species [8-10]. As a basis for the development of molecular tools to study H. conoideum populations (irrespective of developmental stage), we have characterized the complete mt genome of this parasite, compared this genome with those of selected trematodes and undertaken a phylogenetic analysis of concatenated amino acid sequence data for 12 protein-coding genes to assess the genetic relationship of H. conoideum with these other trematodes.

Methods

Parasites and DNA isolation

H. conoideum adults were collected from the intestine of a naturally infected free-range duck in Hubei province, China, in accordance with the Animal Ethics Procedures and Guidelines of Huazhong Agricultural University. These worms were washed in physiological saline and identified morphologically according to existing morphological descriptions [11]. A reference specimen was stained and mounted [12] and the remaining specimens were fixed in 70% (v/v) ethanol and stored at −20°C until use [8]. Total genomic DNA was extracted from one specimen using E.Z.N.A.® Tissue DNA Kit. To provide further identification for this specimen, the ITS-2 region was amplified and sequenced [13], it was identical to a reference sequence available for H. conoideum (GenBank accession no. KJ 944311.1).

Amplification and sequencing of partial cox1, cox3, nad4, nad5 and rrnS

Initially, ten oligonucleotide primers (Table 1) were designed to regions of the mt genome of Fasciola hepatica [14], in order to amplify short fragments from the cox1, cox3, nad4, nad5 and the small subunit of ribosomal RNA (rrnS) genes (Table 1). PCR (25 μl) was performed in 10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 8.4), 50 mM KCl, 4 mM MgCl2, 200 mM each of dNTP, 50 pmol of each primer, 2 U Taq polymerase (Takara) and 2.5 μl genomic DNA or H2O (no-DNA control) in a thermocycler (Biometra) under the following conditions: an initial denaturation at 94°C for 5 min, followed by 30 cycles of 94°C/1 min; 47–50°C/30 s (depending on primer pair), 72°C/1 min, followed by a final extension of 72°C/7 min. Amplicons were sent to Sangon Company (Shanghai, China) for sequencing by using the same forward and reverse primers (separately) as used in PCR.

Table 1.

Sequences of primers used to amplify fragments from Hypoderaeum conoideum

| Primer codes | Sequences(5′ to 3′) | Target gene |

|---|---|---|

| XCCOX3F2 | AGYACDGTDGGDTTRCATTT | cox31 |

| XCCOX3R1 | CANAYATAATCMACARAATGNCA | cox31 |

| XcND4F | GADTCBCCDTATTCDGARCG | nad41 |

| XcND4R | GCHARCCADCGCTTVCCNTC | nad41 |

| TXCCOX1F | GGHTGAACHRTWTAYCCHCC | cox11 |

| TXCCOX1R | TGRTGRGCYCAWACDAYAMAHCC | cox11 |

| Insect12SF | AAWAAYGAGAGYGACGGGCG | rrnS1 |

| Insect12SR | TARACTAGGATTAGATACCC | rrnS1 |

| XcND5F | ATGCGNGCYCCNACNCCNGTDAG | nad51 |

| XcND5R1 | TGCTTVSWAAAAAANACHCC | nad51 |

| XCF2 | TATTAGGAGGTTTGGTGG | cox3-nad42 |

| XCR3 | ATCATAACTACCACATACCCC | cox3-nad42 |

| XCF4 | TAGGTATTGCTTGTTAGCTG | nad4-cox12 |

| XCR2 | TTTAATCGAACCAAGGACAC | nad4-cox12 |

| XCF3 | CATTAGTCACATTTGTATGAC | cox1- rrnS2 |

| XCR10 | GGACTATCTTTTATGATACACG | cox1- rrnS2 |

| XCF1 | GTTATTGGGTTTAGGACTCGG | rrnS - nad52 |

| XCR8 | ACTAACACCGTATTCAACTC | rrnS - nad52 |

| XCF9 | TTTCTCTTTGTGGTTTGCCG | nad5-cox32 |

| XCR1 | TATTAGGTTGTGGTACCCC | nad5-cox32 |

Primer pairs (top to bottom) used to amplify fragments; 1short regions amplified by PCR from cox1 (494 bp), cox3 (140 bp), nad4 (440 bp), nad5 (529 bp) and rrnS (383 bp). 2large fragments that were amplified by long-range PCR from cox3-nad4 (2048 bp), nad4-cox1 (4664 bp), cox1-rrnS (2352 bp), rrnS-nad5 (2272 bp) and nad5-cox3 (1752 bp).

Long-PCR amplification and sequencing

Ten additional primers (see Table 1) were then designed from the sequences obtained, and used to amplify genomic DNA (~40-80 ng) from five regions (see Table 1) by long-PCR; PCRs (25 μl) were performed in a reaction buffer containing 2 mM MgCl2, 1× LA Taq Buffer II, 0.4 mM dNTP mixture, 0.8 μM of each primer, 2.5 U LA Taq polymerase (Takara) and 2.5 μl of genomic DNA or H2O (no-DNA control) for 35 cycles of 94°C/30 s (denaturation), 50°C/30 s (annealing) and 72°C/1 min (extension) per kb. Amplicons were cloned into pGEM-T-Easy vector (Promega, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol; inserts were amplified by long-range PCR (employing vector primers M13 and M14) and then sequenced using a primer-walking strategy [15].

Sequence analyses

Sequences were assembled using the software ContigExpress program (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and aligned against the mt genome sequences of other available trematodes (including F. hepatica) using the programs Clustal X v.1.83 [16] to infer gene boundaries. The open reading frames (ORFs) were identified using ORF Finder (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/gorf/gorf.html) employing the flatworm mitochondrial genetic code. Translation initiation and termination codons were identified as described previously [14,17,18]. The secondary structures of the 22 tRNA genes were predicted using tRNAscan-SE and/or manual adjustment [9,19]. The two rRNA genes were identified by comparison with those from the mt genome of F. hepatica [14]. Amino acid sequences of the protein-coding genes were obtained by using the flatworm mt code, and aligned using the program MUSCLE [20] employing default settings.

Sliding window analysis of nucleotide variation

Sequence variability between H. conoideum and F. hepatica was conducted by sliding window analysis using the software DnaSP v.5 [21]. A sliding window analyses was implemented as described previously [22].

Phylogenetic analysis

Amino acid sequences conceptually translated from individual genes of the mt genome of H. conoideum were concatenated and aligned with those from available mt genomes of trematodes, including Clonorchis sinensis (NC_012147) [14,23], Fasciola gigantica (NC_024025) [22], F. hepatica (NC_002546) [14], Opisthorchis felineus (NC_011127) [23], Schistosoma haematobium (NC_008074) [24], Schistosoma japonicum (AF215860) [14], Schistosoma mekongi (NC_002529) [18], Schistosoma spindale (NC_008067) [24], and the cestode Taenia solium (outgroup) (NC_004022.1) [25]. The phylogenetic analysis was conducted using the neighbour-joining (NJ) method employing the Tamura-Nei model [20]. Confidence limits were assessed using bootstrap procedure with 1000 pseudo-replicates for neighbour-joining tree, and other settings were obtained using the default values in MEGA v.6.0 [20]. In addition, maximum parsimony (MP), Bayesian (MB) and maximum likelihood (ML) analyses were implemented as described previously by other workers [20,26,27].

Results

Features of the mt genome of H. conoideum

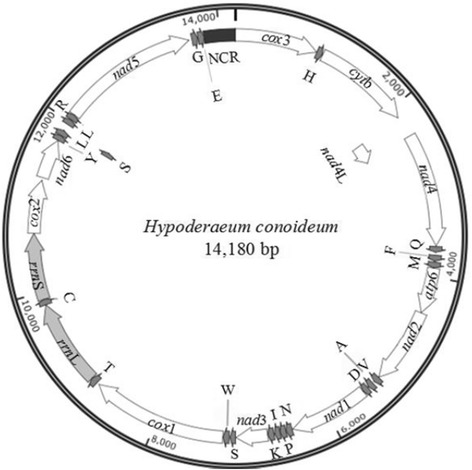

The circular mt genome of H. conoideum (GeneBank accession no. KM_111525) is 14,180 bp in size. It includes 22 tRNA genes, two rRNA genes (rrnS and rrnL), 12 protein-coding genes (cox1-3, nad1-6, nad4L, cytb and atp6) and a non-coding region, but lacks an atp8 gene, and all genes are transcribed in the same direction (Figure 1), which is consistent with other trematodes, such as F. hepatica [14], O. felineus [22] and S. haematobium [24]. The arrangement of the protein-encoding genes is: cox3-cytb-nad4L-nad4-atp6-nad2-nad1-nad3-cox1-cox2-nad6-nad5, which is in accordance with F. hepatica [14], O. felineus [22], S. japonicum [14] and S. mekongi [18], but different from that of S. haematobium and S. spindale [24].

Figure 1.

Organisation of genes in the mitochondrial genome of Hypoderaeum conoideum.

Overlapping nucleotides between the mt genes of H. conoideum ranged from 1 to 40 bp (Table 2), which is the same as other for trematodes, such as F. hepatica [14] and O. felineus [22]. The mt genome of H. conoideum has 26 intergenic spacers, each ranging from 1 to 34 bp in length (Table 2). The nucleotide contents in the mt genome are: 18.92% (A), 11.71% (C), 42.46% (T) and 26.91% (G). The A + T content of protein coding genes and rRNA genes ranged from 59.65% (rrnS) to 68.63% (nad3) (Table 3), and the overall A + T content of the mt genome is 61.4%.

Table 2.

The organization of the mitochondrial genome of Hypoderaeum conoideum

| Gene/region | Positions | Size (bp) | Number of aa 1 | Ini/Ter codons 2 | Anticodons | In 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cox3 | 1-942 | 942 | 314 | ATG/TAG | 0 | |

| trnH | 945-1011 | 67 | GTG | +2 | ||

| cytb | 1017-2126 | 1110 | 370 | ATG/TAG | +5 | |

| nad4L | 2132-2410 | 279 | 93 | GTG/TAG | +5 | |

| nad4 | 2371-3654 | 1284 | 428 | GTG/TAA | −40 | |

| trnQ | 3662-3726 | 65 | TTG | +7 | ||

| trnF | 3759-3824 | 66 | TTG | +32 | ||

| trnM | 3837-3902 | 66 | CAT | +12 | ||

| atp6 | 3906-4424 | 519 | 173 | ATG/TAG | +3 | |

| nad2 | 4428-5294 | 867 | 289 | ATG/TAG | +3 | |

| trnV | 5300-5367 | 68 | TAC | +5 | ||

| trnA | 5391-5454 | 64 | TGC | +23 | ||

| trnD | 5467-5532 | 66 | GTC | +12 | ||

| nad1 | 5533-6435 | 903 | 301 | GTG/TAG | 0 | |

| trnN | 6443-6512 | 70 | GTT | +7 | ||

| trnP | 6516-6581 | 66 | AGG | +3 | ||

| trnI | 6583-6644 | 62 | GAT | +1 | ||

| trnK | 6654-6721 | 68 | TTT | +9 | ||

| nad3 | 6726-7082 | 357 | 119 | ATG/TAA | +4 | |

| trnS1 | 7087-7146 | 60 | TCT | +4 | ||

| trnW | 7158-7225 | 68 | TCA | +11 | ||

| cox1 | 7229-8767 | 1539 | 513 | GTG/TAG | +3 | |

| trnT | 8797-8871 | 75 | TGT | +29 | ||

| rrnL4 | 8873-9851 | 979 | +1 | |||

| trnC | 9852-9916 | 65 | GCA | 0 | ||

| rrnS4 | 9917-10667 | 751 | 0 | |||

| cox2 | 10668-11270 | 603 | 301 | ATG/TAG | 0 | |

| nad6 | 11302-11754 | 453 | 151 | ATG/TAG | +31 | |

| trnY | 11755-11816 | 62 | GTA | 0 | ||

| trnL1 | 11818-11883 | 66 | TAG | +1 | ||

| trnS2 | 11881-11945 | 65 | TGA | −2 | ||

| trnL2 | 11963-12025 | 63 | TAA | +17 | ||

| trnR | 12029-12094 | 66 | ACG | +3 | ||

| nad5 | 12093-13658 | 1566 | 522 | GTG/TAA | −1 | |

| trnG | 13693-13757 | 65 | TCC | +34 | ||

| trnE | 13764-13832 | 69 | TTC | +6 | ||

| Non coding region | 13833-14180 | 348 | 0 |

The inferred length of amino acid sequence of 12 protein-coding genes: 1number of amino acids; 2initiation and termination codons; 3intergenic nucleotides; 4initiation or termination positions of ribosomal RNAs defined by adjacent gene boundaries.

Table 3.

Nucleotide contents of genes and the non-coding region within the mitochondrial genome of Hypoderaeum conoideum

| Gene | A (%) | G (%) | T (%) | C (%) | A + T (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cox3 | 19.85 | 26.96 | 40.02 | 13.16 | 59.87 |

| cytb | 18.83 | 23.87 | 44.86 | 12.43 | 63.69 |

| nad4L | 20.27 | 28.32 | 44.44 | 7.17 | 64.52 |

| nad4 | 16.04 | 28.50 | 44.08 | 11.37 | 60.12 |

| atp6 | 19.08 | 24.08 | 43.55 | 13.29 | 62.62 |

| nad2 | 14.76 | 26.41 | 47.87 | 10.96 | 62.63 |

| nad1 | 16.17 | 29.13 | 45.74 | 8.97 | 61.90 |

| nad3 | 16.53 | 23.53 | 52.10 | 7.84 | 68.63 |

| cox1 | 17.87 | 27.49 | 42.63 | 12.02 | 60.49 |

| rrnL | 23.90 | 26.46 | 36.06 | 13.59 | 59.96 |

| rrnS | 26.76 | 26.76 | 32.89 | 13.58 | 59.65 |

| cox2 | 21.89 | 25.87 | 38.31 | 13.93 | 60.20 |

| nad6 | 14.79 | 25.83 | 45.92 | 13.47 | 60.71 |

| nad5 | 13.81 | 28.26 | 49.55 | 8.38 | 63.36 |

| Non coding region | 22.54 | 24.22 | 37.65 | 15.59 | 60.19 |

Protein-coding genes

The H. conoideum mt genome has 12 protein-coding genes, including nad5, cox1, nad4, cytb, nad1, cox3, nad2, cox2, atp6, nad6, nad3 and nad4L. For these protein coding genes, the initiation codon is ATG (seven of 12 protein genes), and GTG (five genes) (Table 2), which is in agreement with other digeneans [14,28]. The termination codon is TAG (seven of 12 protein genes) or TAA (five genes). The most frequently used codon is TTT (Phe), with the frequency of 7.96%, followed by GTT (Val: 5.99%), TGT (Cys: 4.63%), TTG (Leu: 4.30%) and TTA (Leu: 4.00%) (Table 4). The least used codons are GCC (Ala: 0.34%), CAC (His: 0.32%) and CGC (Arg: 0.11%).

Table 4.

Codon usage for 12 protein-coding genes in the mitochondrial genome of Hypoderaeum conoideum

| Codon | Amino acid | Number | Frequency (%) | Codon | Amino acid | Number | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TTT | Phe | 315 | 8.88 | ATT | Ile | 130 | 3.66 |

| TTC | Phe | 46 | 1.30 | ATC | Ile | 21 | 0.59 |

| TTA | Leu | 149 | 4.20 | ATA | Ile | 58 | 1.63 |

| TTG | Leu | 292 | 8.23 | ATG | Met | 117 | 3.30 |

| TCT | Ser | 124 | 3.49 | GTG | Met | 117 | 3.30 |

| TCC | Ser | 21 | 0.59 | ACT | Thr | 46 | 1.30 |

| TCA | Ser | 21 | 0.59 | ACC | Thr | 11 | 0.31 |

| TCG | Ser | 36 | 1.01 | ACA | Thr | 16 | 0.45 |

| TAT | Tyr | 150 | 4.23 | ACG | Thr | 28 | 0.79 |

| TAC | Tyr | 21 | 0.59 | AAU | Asn | 58 | 1.63 |

| TAA | Stop | 3 | 0.08 | AAC | Asn | 8 | 0.23 |

| TAG | Stop | 9 | 0.25 | AAA | Asn | 25 | 0.70 |

| TGT | Cys | 105 | 2.96 | AAG | Lys | 52 | 1.47 |

| TGC | Cys | 13 | 0.37 | AGT | Ser | 75 | 2.11 |

| TGA | Trp | 34 | 0.96 | AGC | Ser | 15 | 0.42 |

| TGG | Trp | 78 | 2.20 | AGA | Ser | 25 | 0.70 |

| CTT | Leu | 65 | 1.83 | AGG | Ser | 65 | 1.83 |

| CTC | Leu | 4 | 0.11 | GTT | Val | 209 | 5.89 |

| CTA | Leu | 19 | 0.54 | GTC | Val | 21 | 0.59 |

| CTG | Leu | 43 | 1.21 | GTA | Val | 59 | 1.66 |

| CCT | Pro | 44 | 1.24 | GCT | Ala | 69 | 1.94 |

| CCC | Pro | 25 | 0.70 | GCC | Ala | 17 | 0.48 |

| CCA | Pro | 11 | 0.31 | GCA | Ala | 20 | 0.56 |

| CCG | Pro | 21 | 0.59 | GCG | Ala | 32 | 0.90 |

| CAT | His | 44 | 1.24 | GAT | Asp | 66 | 1.86 |

| CAC | His | 9 | 0.25 | GAC | Asp | 4 | 0.11 |

| CAA | Gln | 13 | 0.37 | GAA | Glu | 18 | 0.51 |

| CAG | Gln | 19 | 0.54 | GAG | Glu | 61 | 1.72 |

| CGT | Arg | 44 | 1.24 | GGT | Gly | 140 | 3.94 |

| CGC | Arg | 2 | 0.06 | GGC | Gly | 23 | 0.65 |

| CGA | Arg | 5 | 0.14 | GGA | Gly | 43 | 1.21 |

| CGG | Arg | 14 | 0.39 | GGG | Gly | 101 | 2.85 |

Transfer RNA and ribosomal RNA genes, and non-coding regions

The H. conoideum mt genome encodes 22 tRNAs; all of them have a typical cloverleaf structure. The length of 22 tRNA genes ranges from 60 bp to 75 bp (Table 2). There are intergenic and overlapping nucleotides between adjacent tRNA genes (Table 2). The rrnS and rrnL are 751 bp and 979 bp in length, respectively (Table 2). The location of rrnS is between tRNA-Cys and cox2, and that of rrnL is between tRNA-Thr and tRNA-Cys, which is the same as other trematodes. In contrast to some other trematodes (two AT-rich regions), such as F. hepatica and F. gigantica [14,23], O. felineus [22] and S. haematobium [24], there is only one AT-rich region (348 bp) in the mt genome of H. conoideum, which is located between tRNA-Glu and cox3 (Figure 1 and Table 2), with an A + T content of 60.19% (Table 3).

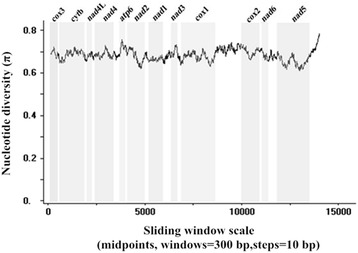

A comparison of nucleotide variability between H. conoideum and F. hepatica

A sliding window analysis of H. conoideum and F. hepatica using complete mt genomes showed the nucleotide diversity Pi (π) for 12 protein-coding genes (Figure 2). It indicated that the highest level of the mt sequence variability was within the gene atp6, and the lowest was within nad5. In our study, the most conserved protein-coding genes are cox1, nad2 and nad5, and the least conserved are atp6 and nad3.

Figure 2.

Sliding window analysis of complete mt genome sequences of Fasciola hepatica and Hypoderaeum conoideum . The black line indicates nucleotide diversity in a window of 300 bp (10 bp steps). Gene regions (grey) and boundaries are indicated.

Phylogenetic relationships

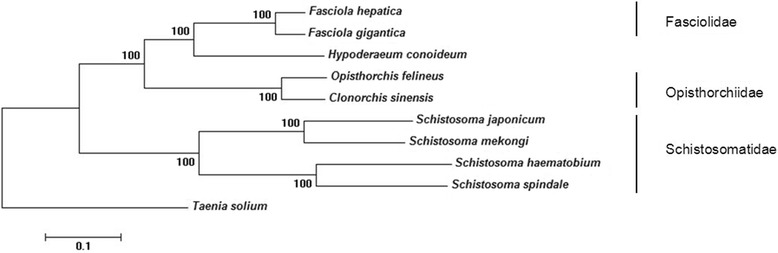

We used concatenated amino acid sequence data representing 12 mt protein-coding genes of H. conoideum, eight other digeneans (C. sinensis, F. gigantica, F. hepatica, O. felineus, S. haematobium, S. japonicum, S. mekongi and S. spindale) and one tapeworm (T. solium) for a selective analysis of genetic relationships (Figure 3). The tree reveals two large clades with strong support (100%): one contains four members representing two families (Fasciolidae and Opisthorchiidae) and H. conoideum; the other clade contains four members of the Schistosomatidae. In the present analysis, H. conoideum had a relatively close genetic relationship with F. hepatica and other members of the Fasciolidae, followed by Opisthorchiidae, and then the Schistosomatidae. There was no difference in tree topology using the ML, MB and MP methods of analysis (not shown).

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic relationship of Hypoderaeum conoideum with selected trematodes; based on concatenated amino acid sequence data representing 12 protein-coding genes by neighbor-joining analysis, using Taenia solium as an outgroup. Nodal support values are indicated (%); the bar indicates amino acid substitution per site.

Discussion

The present characterization of the mt genome of H. conoideum provides a basis for addressing questions regarding the biology, epidemiology and population genetics of Hypoderaeum spp. In addition, it will also assist in supporting taxonomic studies of Hypoderaeum spp. of other animals (e.g., chickens, ducks, geese and humans) as well as in tracking life cycles by identifying larval stages in different intermediate hosts using molecular tools.

Assisted by sliding window analysis, PCR primers could be selectively designed to regions conserved among different trematode species and flanking variable regions in the mt genome that are informative (based on sequencing from a small number of individuals from particular populations). PCR-coupled single-strand conformation polymorphism (SSCP) analysis [29] could then be employed to screen large numbers of individuals representing different populations and, based on such an analysis, samples representing all detectable genetic variability could be selected for subsequent sequencing and analyses. Such an approach has been applied to study the genetic make-up of the blood fluke S. japonicum from seven provinces in China [30,31].

Now that the H. conoideum mt genome is available, it would be interesting to undertake a comprehensive study of this morphospecies from various host species from different countries by integrating morphological data with PCR-based genetic analyses of adult worms and larval stages (from intermediate hosts) to begin to understand the epidemiology and ecology of H. conoideum. In addition to conducting targeted mt genetic analyses, it would also be useful to include analyses of sequence variability in the two internal transcribed spacers (ITS-1 and ITS-2), 18S and 28S of nuclear ribosomal DNA, because, for trematodes, these markers usually allow specific identification of trematodes. Importantly, although H. conoideum is recognized as a species, it is possible that cryptic species of this taxon might exist. This proposal could be tested using the mt markers defined here, together with ITS-1 and/or ITS-2.

Conclusions

Our analysis showed that H. conoideum is genetically closely related to F. hepatica comparing with other trematodes. The mt genome of H. conoideum should be useful as a resource for comparative mt genomic studies of trematodes and DNA markers for systematic, population genetic and epidemiological studies of H. conoideum and congeners.

Acknowledgements

Sincere thanks to Professor Ian Beveridge for comments on the manuscript and assistance with the staining of trematodes. Thanks to Ross Hall and Namitha Mohandas for bioinformatic assistance. This work was supported by the “Special Fund for Agro-scientific Research in the Public Interest” (Grant no. 201303037), “Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities” (Program. 2013PY059) and the Australian Research Council (RBG).

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

RF conceived and designed the study. XY and RBG wrote the manuscript with input from other coauthors. XY, LXW, KXZ and LC performed the experiments and analyzed the data. MH assisted in study design and editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Xin Yang, Email: 695237569@qq.com.

Robin B Gasser, Email: robinbg@unimelb.edu.au.

Anson V Koehler, Email: anson.koehler@unimelb.edu.au.

Lixia Wang, Email: 448472171@qq.com.

Kaixiang Zhu, Email: 1165713714@qq.com.

Lu Chen, Email: 592591293@qq.com.

Hanli Feng, Email: 610579870@qq.com.

Min Hu, Email: mhu@mail.hzau.edu.cn.

Rui Fang, Email: fangrui19810705@163.com.

References

- 1.Sorensen RE, Curtis J, Minchella DJ. Intraspecific variation in the rDNA its loci of 37-collar-spined echinostomes from North America: implications for sequence-based diagnoses and phylogenetics. J Parasitol. 1998;84(5):992–7. doi: 10.2307/3284633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steele JH. CRC Handbook Series in Zoonoses. Section C: Parasitic Zoonoses (Vol. III) Boca Raton, Florida, USA: CRC Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yamaguti S. Systema helminthum (Vol. I): part I. The digenetic trematodes of vertebrates. New York, USA: Interscience Publishers Inc.; 1958. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rim HJ. Echinostomiasis. Boca Raton, Florida, USA: CRC Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harinasuta T, Bunnag D, Radomyos P. Bailliere's clinical tropical medicine and communicable diseases. 1987. Intestinal fluke infections; pp. 695–721. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yokogawa M, Harinasuta C, Charoenlarp P. Hypoderaeum conoideum (Block, 1782) Diez, 1909, a common intestinal fluke of man in the north-east Thailand. Jpn J Parasitol. 1965;14:148–53. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nolan MJ, Cribb TH. The use and implications of ribosomal DNA sequencing for the discrimination of digenean species. Adv Parasitol. 2005;60:101–63. doi: 10.1016/S0065-308X(05)60002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu GH, Wang Y, Song HQ, Li MW, Ai L, Yu XL, et al. Characterization of the complete mitochondrial genome of Spirocerca lupi: sequence, gene organization and phylogenetic implications. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:45. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-6-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu M, Chilton NB, Gasser RB. The mitochondrial genomes of the human hookworms, Ancylostoma duodenale and Necator americanus (Nematoda: Secernentea) Int J Parasitol. 2002;32(2):145–58. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7519(01)00316-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saijuntha W, Sithithaworn P, Duenngai K, Kiatsopit N, Andrews RH, Petney TN. Genetic variation and relationships of four species of medically important echinostomes (Trematoda: Echinostomatidae) in South-East Asia. Infect Genet Evol. 2011;11(2):375–81. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2010.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chai JY, Shin EH, Lee SH, Rim HJ. Foodborne intestinal flukes in Southeast Asia. Korean J Parasitol. 2009;47(Suppl):S69–102. doi: 10.3347/kjp.2009.47.S.S69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang GL. Laboratory diagnostic techniques of parasites. Feeding Livestock. 2013;3:39–43. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tantrawatpan C, Saijuntha W, Sithithaworn P, Andrews RH, Petney TN. Genetic differentiation of Artyfechinostomum malayanum and A. sufrartyfex (Trematoda: Echinostomatidae) based on internal transcribed spacer sequences. Parasitol Res. 2013;112(1):437–41. doi: 10.1007/s00436-012-3065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Le TH, Blair D, McManus DP. Complete DNA sequence and gene organization of the mitochondrial genome of the liverfluke, Fasciola hepatica L. (Platyhelminthes; Trematoda) Parasitology. 2001;123(6):609–21. doi: 10.1017/S0031182001008733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hu M, Jex AR, Campbell BE, Gasser RB. Long PCR amplification of the entire mitochondrial genome from individual helminths for direct sequencing. Nat Protoc. 2007;2(10):2339–44. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25(24):4876–82. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ai L, Weng YB, Elsheikha HM, Zhao GH, Alasaad S, Chen JX, et al. Genetic diversity and relatedness of Fasciola spp. isolates from different hosts and geographic regions revealed by analysis of mitochondrial DNA sequences. Vet Parasitol. 2011;181(2–4):329–34. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2011.03.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Le TH, Blair D, Agatsuma T, Humair PF, Campbell NJ, Iwagami M, et al. Phylogenies inferred from mitochondrial gene orders-a cautionary tale from the parasitic flatworms. Mol Biol Evol. 2000;17(7):1123–5. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lowe TM, Eddy SR. tRNAscan-SE: a program for improved detection of transfer RNA genes in genomic sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25(5):955–64. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.5.0955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edgar RC. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(5):1792–7. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Librado P, Rozas J. DnaSP v5: a software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1451–2. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu GH, Gasser RB, Young ND, Song HQ, Ai L, Zhu XQ. Complete mitochondrial genomes of the ‘intermediate form’ of Fasciola and Fasciola gigantica, and their comparison with F. hepatica. Parasit Vectors. 2014;7:150. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-7-150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shekhovtsov SV, Katokhin AV, Kolchanov NA, Mordvinov VA. The complete mitochondrial genomes of the liver flukes Opisthorchis felineus and Clonorchis sinensis (Trematoda) Parasitol Int. 2010;59(1):100–3. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2009.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Littlewood DT, Lockyer AE, Webster BL, Johnston DA, Le TH. The complete mitochondrial genomes of Schistosoma haematobium and Schistosoma spindale and the evolutionary history of mitochondrial genome changes among parasitic flatworms. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2006;39(2):452–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2005.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakao M, Sako Y, Ito A. The mitochondrial genome of the tapeworm Taenia solium: a finding of the abbreviated stop codon U. J Parasitol. 2003;89(3):633–5. doi: 10.1645/0022-3395(2003)089[0633:TMGOTT]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yin F, Gasser RB, Li F, Bao M, Huang W, Zou F, et al. Genetic variability within and among Haemonchus contortus isolates from goats and sheep in China. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6(1):279. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-6-279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mohandas N, Pozio E, La Rosa G, Korhonen PK, Young ND, Koehler AV, et al. Mitochondrial genomes of Trichinella species and genotypes-a basis for diagnosis, and systematic and epidemiological explorations. Int J Parasitol. 2014;44(14):1073–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2014.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yan HB, Wang XY, Lou ZZ, Li L, Blair D, Yin H, et al. The mitochondrial genome of Paramphistomum cervi (Digenea), the first representative for the family Paramphistomidae. PLoS One. 2013;8(8):e71300. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gasser RB, Hu M, Chilton NB, Campbell BE, Jex AJ, Otranto D, et al. Single-strand conformation polymorphism (SSCP) for the analysis of genetic variation. Nat Protoc. 2006;1(6):3121–8. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chilton NB, Bao-Zhen Q, Bøgh HO, Nansen P. An electrophoretic comparison of Schistosoma japonicum (Trematoda) from different provinces in the People’s Republic of China suggests the existence of cryptic species. Parasitology. 1999;119(Pt 4):375–83. doi: 10.1017/S0031182099004837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhu XQ, Bøgh HO, Gasser RB. Dideoxy fingerprinting of low-level nucleotide variation in mitochondrial DNA of the human blood fluke, Schistosoma japonicum. Electrophoresis. 1999;20(14):2830–3. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-2683(19991001)20:14<2830::AID-ELPS2830>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]